The first computer designed for the kitchen was manufactured by Honeywell in 1969. A swooping console equipped with a countertop, keypad, and a tiny, narrow screen, the H316 was as big as a washing machine and did little more than archive recipes. At $10,000, it retailed for roughly the same price as a tract house. This spectacle of space-age modernity failed, not surprisingly, to attract consumers.

Eager entrepreneurs tried again during the dot-com boom, introducing a rash of simplified kitchen computers designed to get techwary users online fast. Known as Internet appliances, these computers had no hard drive yet cost as much as a full-fledged PC. The Netpliance iOpener, for example, was aimed at “50-year-olds and above and the female community”—groups seen as needing kinder, gentler, and tightly curtailed access to the web (it connected only to preselected websites). The iOpener sank faster than a half-baked meatloaf.

On the kitchen scene today, the “media fridge” keeps popping up on tech-watch blogs as a symbol of the smart kitchen. Promising to coordinate menu planning with television and web surfing, these hybrid white goods have had limited impact on consumers, although add-on electronic calendars and photo storage devices—virtual magnets for the kitchen’s favorite bulletin board—have been more successful. When it comes to kitchen computing, however, most people simply hook up an ordinary computer or laptop.

The first theorists of the modern kitchen, Catharine Beecher (1800—1878) and Christine Frederick (1883—1970), copied the floor plans of ship galleys and factory floors in their drive to make kitchens more efficient. The first wave of electric appliances was marketed by utility companies to boost energy consumption. Various gadgets were designed to make cooking a meal more like making a car: tool-assisted, time-managed, and scientific. Progressive designers treated the kitchen as a tiny factory where things get made (meals, mainly). Toasters were advertised as aids to production, yet they served to accelerate consumption—of pre-sliced, factory-baked bread.

DAZEY CANARAMIC Counter-mounted can opener

Another gadget tied to processed foods is the can opener. Morphing from modest handheld cranks into dramatic built-in devices, can openers went countertop in the 1930s and 40s, their mechanical guts hiding inside shapely shells inspired by trains and cars. In the 1950s a huge range of design and price options appealed to consumers hooked on tinned vegetables and tail fins.

Today, the kitchen has morphed from factory to information hub. In 2003, Whirlpool CEO Henry Marcy V called the kitchen “the command center of the home.” This space age image has its roots in Whirlpool’s “Miracle Kitchen,” a demonstration project that toured the U.S. in 1957. At the center of the Miracle Kitchen was a planning area housing a telephone, audio-visual remote controls, and a closed-circuit TV monitor. Today, many kitchens include a computer and office niche in their floor plans. Pushing data, images, and brands has supplanted the production of things in the working lives of most middle-class American wage earners. As more and more meals exit their cartons and head straight for the microwave, today’s digital tools zone the kitchen as a place to buy and serve branded goods and mass media. Meanwhile, cooking appliances are going back into hiding in upscale kitchens. Refrigerators masquerade as cabinetry, and “appliance garages” (complete with rolling garage doors) keep smaller machines out of sight, ready for use on ritual occasions, such as the Festival of the Waffle Iron, Midsummer Night’s Popcorn, and the Ultra Slim Fest.

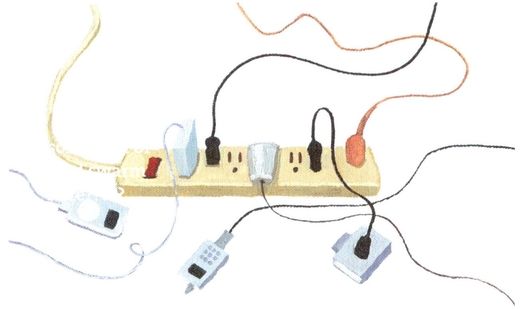

Too many gadgets clutter rather than clarify; the effort required to retrieve, operate, and clean small appliances often outbalances their promise of convenience. “Smart” systems that integrate audio, heating, lighting, and surveillance can be so challenging to use, their owners quickly abandon them. Behind the relative success and failure of

these engineered solutions to domestic tasks loom deeper questions about the computerized home. Media scholar David Morley argues that the soul of the smart house is not intelligence but rather security: both the emotional security of a place in which information and its mysterious machinery is personalized and domesticated, and physical security against the threat of crime, terror, and identity theft. In the contemporary kitchen, paper may be shredded more often than carrots or cheese. Yet, as upscale housing design continues to pursue the ideal of privacy at any cost, real privacy is increasingly undermined by ad ware, web crawling, and online shopping.

MINI PAPER SHREDDER No bigger than a toaster

Meanwhile, the house itself is on the move, with cell phones and iPods becoming “mobile homes” that blow bubbles of ambient privacy around each consumer. The cell phone is the roller bag of communications: its portability and multiple functions allow users to drag their entire media suitcase with them when they leave the house while making them oblivious to the personal space of others. The “cell yell” is the barbaric “Yawp” of the mobile masses.

Technology’s role in the home is not simply to process incoming information while keeping out real and virtual intruders. A really smart house is one that nurtures multiple intelligences: musical, artistic, mathematical, and culinary. Design tools are hibernating on hard drives and servers everywhere, in the form of fonts, image programs, video tools, and more. The home is not only a designed environment but also as an environment for design, whether it’s creating a more beautiful meal or printing a fund-raising flyer.

My fridge is noisy, but it doesn’t talk to me. We do have a computer in the kitchen, however. Everyone in the household uses it for art projects, homework help, and Internet research. Although we shop and pay bills on it, the computer in the kitchen is mainly used for working

with words and images: drafting essays and reports, blogging and checking email, managing photos and doing design. I wrote this book with kids playing to my left and dinner simmering to my right.

Kitchen technology has long based its sale pitches on the freedom that the latest gizmo offers to female consumers. In one ad from the 1950s, a fashionably dressed lady on her way out the door declares, “My time’s my own … my kitchen is Kelvinator!” Feminist historians, however, have noted that labor-saving devices helped raise standards of cleanliness and create new tasks. For example, the widespread embrace of automatic washing machines and dryers encouraged more frequent cleaning of sheets, towels, and pajamas and derailed the commercial out-of-home laundry business.

Not so with the computer in our kitchen. Far from escalating the housework, the downstairs laptop has helped me create pockets of independence and creativity inside the most active service sector of the house. Do you want a smart kitchen? Then stick microchips, web cams, and barcode readers inside your appliances. Do you want smart people? Then put the computer out in full view, where everyone can use it. Especially Mommy. JL

Numerous web-only computers, designed for kitchen use, appeared during the peak of the Internet boom. Consumers never caught on, however, and most models were yanked off the market as the Internet chuck wagon began to crash.

AUDREY Introduced by 3com in 2000, the Audrey was quietly euthanized six months later. Operated with a digital pen and touch screen rather than a keyboard, Audrey was designed to conserve counter space and to attract the eye with her trendy, swoopy “blobject” curves.

EVILLA Equipped with a jaunty upright screen, SONY’s eVilla came and went in 2001. Internet access was limited to websites created by SONY’s business partners—no full-blown surfing allowed. Users couldn’t load their own software onto the appliance, which had no hard drive.

GATEWAY/AOL INTERNET APPLIANCE

Introduced in 2000 and discontinued in 2001, this device wedded specific online content (AOL) with specific hardware (Gateway). It was a marriage that quickly came undone. The perky, Disney-esque curves weren’t enough to warm consumers to this short-range appliance.

ICEBOX Launched in 2000, Salton’s Icebox was a hub connecting a family of smart appliances, including a bread maker, coffeepot, and microwave. The hub could be placed anywhere in the home, so you could bake bread from your bedroom or make popcorn from the john. The model shown here (2004) is no longer available.

CONSCIOUS

CLUELESS