“Thrift, thrift, Horatio! The funeral bak’d meats did coldly furnish forth the wedding table.” Hamlet lobs these lines at a school chum who has come to Denmark for the funeral of Hamlet’s father. Alas, the friend has arrived just as Hamlet’s mother is marrying his father’s brother (and murderer). The lines are spiked with enough irony to make even the most upbeat hostess pause her ice crusher.

Sure, no one’s going to set a wedding table with food from the funeral parlor. Still, doesn’t every buffet carry just a whiff of death warmed over? Prepared in a remote location, resurrected from the deep freeze, or kept on life support for hours in chafing dishes, major party foods suffer a time lag between preparation and presentation; their time, as Hamlet would say, is “out of joint.” Yet these trays and steam tables, with their forced smiles and flagging garnishes, are summoned against all odds to sustain the powerful present tense of ritual and celebration. The wedding ceremony culminates in the contractual miracle of “I do.” A sense of betrayal often follows when the food appears at last in its shiny coffins of elevated steel.

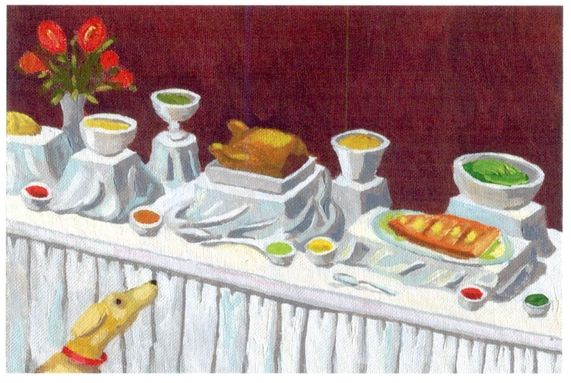

Restrained and tasteful buffet arrangements can help keep the phantoms at bay (ghosts are notoriously attracted to table skirts and Bunsen burners). But a severely minimalist setting can haunt the table with reverse nostalgia, inviting specters of a more gracious time, when seraphs and serifs alike dwelled in the ruffles and signage of the bounteous board. Yes, banish the frou frou—but remember that a few folds of fabric, a length of ivy, or a bit of basketry can revive a table deadened by stacks of square plates and demanding food.

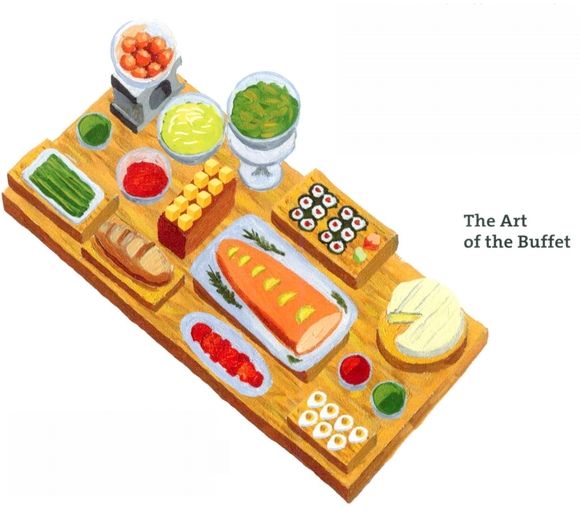

The word “buffet” initially referred to a sideboard, designed not to feed the masses, but rather to show off gold and silver vessels, symbols of solvency in the ancien regime. With the rise of the bourgeoisie in the nineteenth century, the term gradually attached itself to the mode of self-service itself, which began as a feature of the breakfast room and only later became an acceptable form for evening dining. Today, a home buffet cuts down labor, encourages circulation, and

saves valuable real estate in the eating area. Buffets no longer require a dedicated sideboard; a folding table, dining room table, kitchen counter, or other flat surface can get the job done, as long as there is plenty of room for guests to move. The best buffet is a traffic island, not a dead-end street. Buffets, by nature eclectic, can happily house store-bought goods with home-cooked dishes—Hamlet’s “funeral baked meats” next to maiden-voyage casseroles. Vast trays can be punctuated by tiny dishes of brightly colored condiments or salads. Desserts and beverages work best at their own stations.

Plating—the assemblage of plates in the kitchen before serving—is often suited to smaller gatherings in search of formality. While a successful buffet communicates abundance and invite guests to design their own meals, plating casts the chef as the author and curator of a more conscious eating experience. (Take orders in advance to ward against allergy episodes or food fear.) You don’t need to carve swans out of radishes in order to compose an attractive plate. It’s enough to consider a pleasing ratio of tastes, colors, and textures. Keep portions modest: like a well-designed page, an appealing plate often includes some white space. Many guests would prefer to ask for seconds of that delicious cauliflower surprise than be asked to preside over a burial mound of chow.

“Family-style” service brings the buffet right to the table, in large plates and dishes outfitted for direct access. Whereas plating food implies a degree of decorum, distance, and courtship—among ingredients, dishes, and guests—family—style dining celebrates the marriage, amalgamation, and remixing of foods and people. To some over-scheduled households, “family” and “style” may seem like mutually exclusive ideas. Why bother putting food in tureens and serving dishes when the little barbarians treat their plates as troughs? If every grand buffet, like Hamlet’s, risks being haunted by ghosts of weddings past and divorces future, mid-week leftovers mirror mid-life marriages that have “let themselves go.” At weeknight feedings, exhausted cooks are known to slap down food directly from cook pots, take-out containers, or yesterday’s microwaved Tupperware in order to save time and just get the whole dinner thing over with.

“Thrift, thrift, Horatio”—but at what cost? Order and beauty can find a place at the table along with motorized elbows, outside voices, and homework goblins. There’s no need to go the extra mile—a mere inch of extra thought can sweeten the mood and salt the appetite. Simply transferring a carry-out or carry-forward dinner to a favorite serving dish can lay the spirits of the dead to rest while brightening the table with a precious sense of hope. Even on Wednesdays. JL

CLASSIC DRAPE This old catering trick creates a variety of levels on the table in order to generate visual drama as well as varied access to the food. First, dress the table with a base cloth. Next, place one or more low, sturdy boxes on top of the main table linen. Swathe the boxes with artfully draped pieces of complementary textiles to build tiny stages for food and flowers.

The Art of the Buffet

FALLING WATER Cut the frills, and use bricks, blocks, planks, slabs of granite, and other materials to create modernist elevations for minimalist meals.

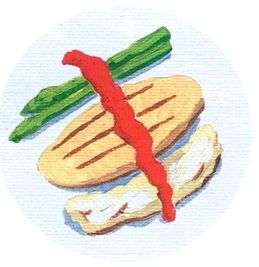

Arranging food on individual plates in the kitchen is a restaurant technique suitable for home dinner parties. Plating creates drama and formality as well as portion control. Line, color, pattern, and height can add life to a plate immobilized by meat. Boneless chicken breast needs all the help it can get.

TOWER OF CHICKEN Upscale restaurants charge more for food stacked high on the plate. You can build height into your own entree by placing the main element on a bed of greens or a mound of mush.

FLAG OF CHICKEN Even ordinary food feels more modern when laid out in stripes. Unify the design with a ribbon of sauce.

TIME FOR CHICKEN The square meal is really round: served on a basic circle, the starch stands at ten o‘clock, the meat at two o’clock, and the vegetables anchor the plate at six o’clock.

CHICKEN NAPOLEON A traditional “Napoleon” is a layered pastry. Today, the term is applied to any artful stack of food elements.

BREAST OF CHICKEN IN RECEDING LANDSCAPE

Renaissance landscapers used variations in size in order to build the illusion of depth into gardens and parks. You can use the same tricks when you’re plating your food. Put low foods in the foreground of the plate, and build up height towards the back. Prop up your protein against a mountain of carbs.

When you simply must consume fast food on the go, use these simple designs inspired by exciting restaurant trends to elevate the humblest meal into a work of art.

TALL ORDER Mount burger on a carry out container; hold elements together with a plastic straw. Garnish with fries for added height.

SPA CUISINE Arrange low-calorie toppings in a sleek stripe. (Stash the patty in your purse for later.)

FUSION CUISINE Create a Japanese flag by applying a thin layer of ketchup to a naked burger.

SLOW FOOD Make your own open-faced traffic light with burger, buns, and condiments.

The wine box is a good design with a bad image. The technology was introduced in Australia in 1965, where today, half of all wine is sold in a box. (Australians and New Zealanders also were early adapters of screw tops and plastic corks.) Wine boxes are popular in England, Italy, Sweden, Chile, and other countries worldwide, but not in the U.S., where the mystique of glass and cork weighs heavy—and where many consumers can’t shake the product’s frat house hangover.

Wherein lies the appeal of the wine box? First, it’s cheap. Although premium wine boxes contain a higher grade of product than the giant cartons of swill served to underage drinkers, all boxed wines are sold as value products. (At the lower end of the wine spectrum, the glass bottle can cost more than the wine inside.) Second, the box is convenient. It’s easy to open (no tools required), and the wine keeps for a month after it’s been opened (no pressure to polish off a whole bottle at breakfast). The box’s light weight lowers shipping costs and the associated use of petroleum as well as saving your own back. (Carry it to your local beach, pool, park, or preschool.) Finally, a box takes up less space than a bottle or jug, further conserving on shipping while saving shelf space.

Despite these compelling advantages, boxed wine needs a status boost. Manufacturers are rebranding the box, reaching out to a rising generation of consumers who may be willing to abandon the bottle in favor of convenience, ecology, and price (at least on weeknights). Animal themes (rabbits, fish, kangaroos) add a frisky rural finish to some of the new upscale cartons. Target has introduced a product called The Cube—a beverage that’s proud of its box. DTOUR, developed by celebrity chef Daniel Boulud, cuts corners altogether by using a tall cardboard cylinder in place of a straight-sided carton.

Although these products are notching up the image of the box, none of them is a collector’s item. The packaging is intended to hold liquids for no more than a year, after which point the plastic may start leaching into the wine. (Look for the use-by date.) Glass is far easier to recycle than either type of wine box, but the shipping costs still push the boxes ahead on the ecological balance sheet.

Hosts who are squeamish about putting a bladder on their holiday buffet or a juice box on their date-night dining table may be tempted to decant their boxed wine in the kitchen. Soon, however, the box might start feeling at home anywhere. EL

BLADDERS AND JUICE BOXES There are two kinds of wine box. The first, called “bag in a box,” is also known as a “bladder” or “cask.” It harkens back to the ancient technique of carrying wine in an animal skin. The other type, “asceptic packaging,” is a resin-impregnated paper container equipped with an integral spout or screw top. Known by the trade name Tetra Pak, it is also called a “juice box,” owing to its family relation to toddler-style juice bombs.

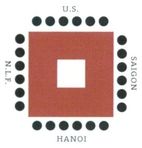

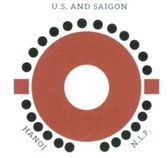

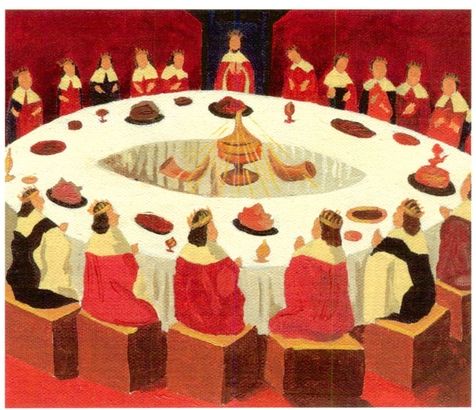

The Vietnam Peace Conference of 1969 was preceded by widely publicized deliberations over table arrangements. The first plan centered around a great rectangular conference table, the kind of massive megalith familiar from peace talks and smorgasbords since the Middle Ages. Sovereigns, CEOs, and divorce lawyers alike favor the built-in formality of the long table, which establishes a clear head and forces warring parties to speak face-to-face while staying out of strangling reach. In search of a more democratic seating plan, the Vietnamese negotiators moved from rectangles to circles. Round tables, too, have a long history. In a legendary feat of furniture design, Merlin the magician created a round table for King Arthur and his knights, using the equal seating to reduce bickering and food fights among his top warriors. The Vietnam ambassadors went back and forth with various table arrangements, including squares, diamonds, and divided circles. In an Arthurian mood, they finally agreed on a big circle—bisected, however, by two small freestanding rectangular tables that split the meeting space into clear sides. (The talks failed anyway.)

Home life is war by other means, whether the problem is money in the bank, socks on the floor, or a dreaded bout of MFS (Me First Syndrome). The philosopher Hannah Arendt wrote in 1959, “To live together in the world means essentially that a world of things is between those who have it in common, as a table is located between those who sit around it; the world, like every in-between, relates and separates men at the same time.” Tables bring people together, but they also help keep them apart, creating an open space and a neutral zone across which conflicting parties can search for peace.

U.S. POSITION: 2 SIDES

HANOI POSITION: 4 SIDES

COMPROMISE

FINAL ARRANGEMENT

In the nineteenth century, dining rooms were associated with the man of the house. They often sported hunting themes, to honor the primacy of meat and the victorious return of the breadwinner at the dinner hour. Today, most dining rooms are designed to house a rectilinear table; the proverbial square meal sits well on a rectangle.

Circles, in contrast, have no natural focal point. They often nest in kitchens, where their small footprint and continuous circumference suits the morning traffic flow of bagels and backpacks. An oval table is just a parallelogram on drugs, but its soft lines can absorb additional chairs more easily than its angular counterparts.

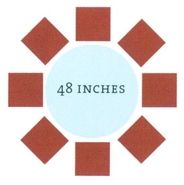

Going against the grain of the traditional dining room, Ina Garten (aka “the Barefoot Contessa”) prefers round tables for small dinner parties. “With six people, you can really get a conversation going. The ideal table for six or seven is a 48-inch round, because everyone is equally engaged in the conversation. If people are a little crowded, it feels even more intimate.” For larger gatherings, she recommends renting a few round tables (together with the necessary linens) from a party supplier.

KNIGHTS OF THE ROUND TABLE Over the ages, artists have imagined King Arthur’s table in various ways. Some represent it as a huge flat disk, while others depict an open donut shape. Our rendering is based on an illumination from a manuscript of Lancelot-Grail, completed in 1470. The circular arrangement is democratic in spirit, but Arthur got the best chair.

A round table also makes a great office accessory. If you have your own office and your job draws a lot of face time, try squeezing a small round table into a front corner. People won’t even know why they’re smiling, but the circular setting can really break the ice, whether you’re speaking with an important client or a testy colleague. Retreat behind your big desk to stake out a safe position.

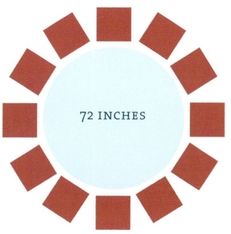

Small circles may be true conversation pieces, but the ungainly disks favored by banquet halls are weapons of mass construction. The 72-inch round (standard fare at weddings and galas) conserves real estate and allows ten to twelve guests to sit together. Alas, its fold-out acreage seems destined to hold you hostage to the old guy with the hearing aid to your right, leaving the hipsters on the opposite side of the table to wink and sparkle faintly across a battlefield of glassware and super-sized flora.

Whether your table is shaped like an amoeba or a boomerang, the search for mealtime order remains a holy grail in most households. Assigned seating quietly sets household order on the firm footing that only four legs or a sturdy pedestal can provide. The reigning adults of the household often have better conversations if they occupy two corner seats, an arrangement that maps a happy diagonal between side-by-side cuddling and face-to-face discussion.

Everyone should clear his own plate. Or else it’s war. JL

Talk to anyone you like

Chained to your immediate neighbors

When shopping for a table, pay attention to the legs. The number of people that can sit at a table is affected not only by the size of the tabletop, but by the placement of the legs. Generally, legs that are set in from the edge are more accommodating to chairs, in contrast with legs pushed out to the perimeter.

MÉNAGE A TROIS Jean Prouve’s 28-inch round Gueridon table, designed c. 1946, is scaled for intimate conversations. The sexily splayed legs make it awkward to fit more than three chairs around the table, although the circumference would easily seat four.

URBAN RENEWAL Eero Saarinen’s pedestal tables, designed in 1956, keep table legs completely out of the way. Saarinen explained, “The underside of typical chairs and tables makes a confusing, unrestful world. I wanted to clear up the slum of legs.”

ORDINARY OCCASIONS Considered as a functional object, the woefully pedestrian banquet table is not such a terrible design. The strangely shaped legs not only accommodate the folding and closing mechanism, but allow chairs to be pushed in all around the perimeter. Tablecloth required.

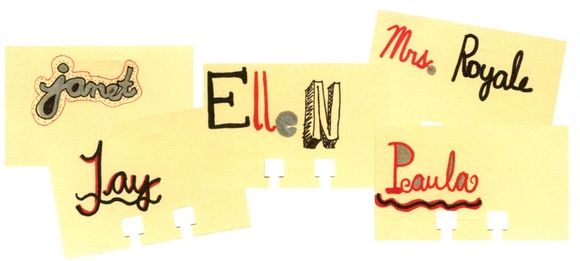

PLACE CARDS Some hosts feel that place cards are too fussy, formal, or controlling for a casual dinner party, yet using this simple planning tool can curb the chaos that erupts as your guests transition from cocktail hour to the dinner table. HANDMADE A place card need not be elaborate—have your kids make them with Sharpies and index cards, or write them yourself on a piece of origami paper or any small slip of paper or cardstock. These were penned on vintage rolodex cards by Ruby, age 9.

ENTERTAINING: THE SPEED-DATING WAY Speed-dating was invented in order to maximize on people’s intuitive sense of connection (or disconnection) with each other and to cut down on wasted steaks. The technique was invented by Aish HaTorah, an outreach group whose contribution to a Jewish tomorrow was sealed when they figured out how to cut the ancient art of matchmaking to the bare minimum: gather a group of singles; allow them to talk for as little as three minutes; then ring the bell and make them move on to the next candidate.

Since its inception in Beverly Hills in 1998, speed-dating has not only gone secular; it has also migrated to other forms of social interaction. In London, the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment decided to apply the principles of speed-dating to match skittish architects with bottom-line developers. The two groups were corralled into a banquet hall, where they proceeded to rotate through their pitches in order to find common ground without Power Points or power lunches.

Speed-dating is to the blind date what the cocktail party is to the formal dinner. An extended meal around a shared table can lock you and your guests into a miserable staring contest where the only out is an emergency call from the baby sitter (just set your cell on alarm). At a cocktail party, however, guests can circulate freely until they find a conversation that sticks. Potlucks and buffets incorporate dinner into the evening without forcing familiarity over too many hours. If you want the full orchestral rhythm of a classic dinner party without the claustrophobia, try moving into another room for dessert.

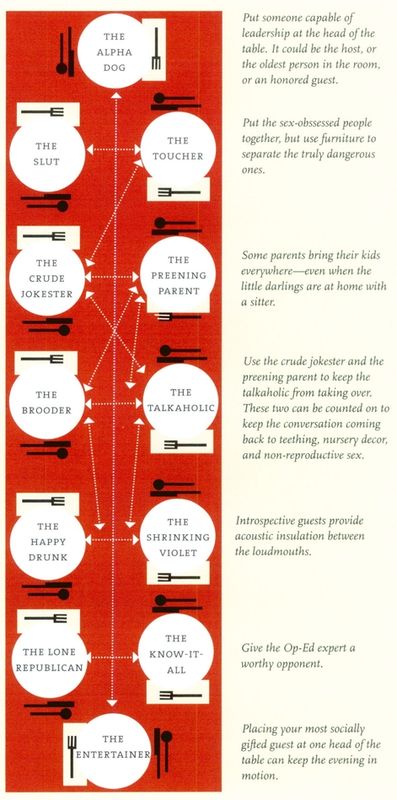

SEATING CHART

Place your guests carefully to generate energy, buzz, and even mischief. Party politics? Global swarming? Some really foul play?

MOMMY CARROT

AUTHENTIC

BABY

CARROT

Yanked from

the ground in

its infancy.

BABY

CARROT

Yanked from

the ground in

its infancy.

BABY-CUT CARROTS

A litter of young ‘uns

machined from a mature

carrot.

A litter of young ‘uns

machined from a mature

carrot.