Everybody who uses a computer knows something about fonts. It didn’t used to be that way—typefaces were once the exclusive domain of professional designers. Today, Times Roman and Helvetica are ubiquitous, and tens of thousands of other fonts are available for use by anyone who can buy the software. How is even the most eager font nerd supposed to make sense of these endless variations?

Students in my basic typography courses often start the semester with a question like this: “When will we learn what typefaces mean? You know, like, what font should we use for a particular job?”

Their eager faces cloud with disappointment at my cold reply: “Most typefaces don’t mean anything at all.”

As I see it, the vast and overwhelming world of fonts can be divided into two basic categories: coffee and donuts. Coffee is dark, acidic, and invigorating. Donuts are soft, sweet, and sticky, causing a brief elevation in mood quickly followed by gas and low-grade depression.

Certain typefaces aim to be meaningful: wedding scripts, fake neon, distressed “garage fonts” of various sorts, and letters built from twigs, flames, or soccer balls. Most typefaces, however, are abstract, aiming only to express the basic shapes of the alphabet in a distinctive and consistent way. End of story. Classical serif typefaces like Garamond and Caslon as well as modern sans serifs like Helvetica and Univers are, essentially, abstract.

Once in a while, a designer uses letterforms to brilliantly mirror the content at hand. The logotype for Dunkin’ Donuts, designed in the 1970s, still holds strong today as an indelible signifier of deep-fried, sugar-glazed bakery treats. The logo’s pudgy, rounded letterforms are packed together in a neat rectangle, like donuts in a box. The Tootsie Roll logotype is another rare instance of this form/content synergy. It employs Oswald Cooper’s eponymous 1930s typeface Cooper Black (also used extensively on t-shirts in the 1970s). A few seductive, sugar-loaded examples like these can send a designer down a lifelong search for meaningful typography.

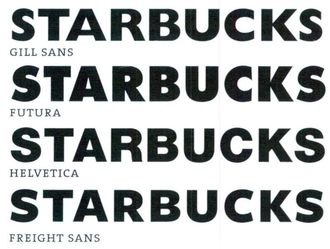

Most logotypes bear no resemblance whatsoever to their content, yet they nonetheless become linked in our minds with a company or product—even when the letterforms themselves are not only abstract, but utterly commonplace. The letters in the Starbucks logo are similar to those in Futura, a geometric typeface designed in Germany in the 1920s, at the time of the Bauhaus. Futura, one of the world’s most widely used typefaces, appears today in hundreds of corporate logotypes. The Starbucks logo also resembles Freight Sans, a font designed by Joshua Darden in 2005. At first glance, the typefaces shown below look similar, yet designers learn to tell them apart by studying details such as the letter R.

A well-designed font is like a prize-winning potato. Most people can’t tell one potato from another. But potato experts surely can, as demonstrated each August at agricultural fairs around the land. The state or county fair is a late-summer rite that features carnival rides, cotton candy, pregnant cows, and quiet air-conditioned halls filled with perfect vegetables. There, displayed on tier after tier of shelving, sit dozens of carrots, onions, peppers, and potatoes, proudly arrayed on ruffled paper plates. To me, a potato is just a potato. I can’t see what makes one brown-eyed spud different from the next. Yet the judges will come through and endow one proud platter of tubers with a bright blue ribbon.

Graphic designers bring that same appreciation to letterforms. Typefaces don’t need to be fancy or original to do their job. A few basic fonts are all you need to create beautiful and distinctive publications, from reports and proposals to flyers, invitations, bomb threats, and books of poetry. If fancy fonts are important to you, try washing one down with a brisk cup of coffee on the side. EL

SMOOTH sexy spuds

SPECIES: GARAMOND

ORIGIN: France, 1500s; Claude Garamond

HABITAT: This hardy Renaissance font thrives in books of prose or poetry.

DISTINCTIVE MARKINGS: Pretty but tough, these letters are built with sturdy calligraphic strokes.

Proud plump POTATOES

SPECIES: CASLON

ORIGIN: England, 1734-70; William Caslon

HABITAT: Caslon was popular during the American Revolution; use it for drafting declarations, constitutions, and whatnot.

DISTINCTIVE MARKINGS: Slim, sharp serifs and upright forms.

blunt bland BLOBS

SPECIES: TIMES ROMAN / TIMES NEW ROMAN

ORIGIN: England, 1931; Stanley Morison

HABITAT: Created for a London newspaper, Times Roman became the ubiquitous font of desktop publishing in the 1980s.

DISTINCTIVE MARKNGS: Its pinched, narrow body was designed to save space on cheap newsprint. Avoid it when you want to make your publications different from everyone else’s.

HOT crispy fries

SPECIES: GILL SANS

ORIGIN: England, 1928; Eric Gill

HABITAT: Britain’s most popular sans serif typeface, it is known as the Helvetica of the U.K.

DISTINCTIVE MARKINGS: Plain and simple but not severe.

RIPE ROUND rhizomes

SPECIES: FUTURA

ORIGIN : Germany, 1927; Paul Renner

HABITAT: This strict geometric typeface, designed in the Bauhaus era, is used in logos, books, signage, and info graphics around the world.

DISTINCTIVE MARKINGS: Look for the round O and the pointy Ms and Ns.

sleek salty STARCH

SPECIES: HELVETICA

ORIGIN: Switzerland, 1957; Max Miedinger

HABITAT: Helvetica is at home absolutely everywhere: banks, airports, trendy t-shirts, and New York City garbage trucks.

DISTINCTIVE MARKINGS: The teardrop bowl of the lowercase A and the oddly curved leg of the uppercase R are signature features of this classic Swiss typeface.

NO EXIT What if a signage system could guide us through our interpersonal landscapes?