A prominent graphic designer once created elegant interior signs for a concert hall, pointing the way to the gift shop, the restrooms, the auditorium, and more. The architect and the client loved the signs because they were set into the walls flush with the outer surface—no ugly plaques or panels were sticking out and casting shadows. Unfortunately, the signs were so discreet they almost disappeared. Many people weren’t noticing them, so the institution erected free-standing stanchions around the building, emblazoned with the same text that was so subtly embedded in the walls behind them.

“Signage” is a design specialty devoted to guiding people through airports, hospitals, schools, and other public places. In a major building project, a signage specialist works to brand the building as well as create room markers and directional signs designed to lead users where they want to go. Signs have attitude and personality. They can command, scold, welcome, or resassure. Laws governing the number, placement, size, and visual treatment of signs help keep everyone moving smoothly, including people with disabilities.

Despite all of the money and expertise directed at signage, evidence of confusion can be observed in nearly any sparkling new edifice or renovated office suite. Every time you see a piece of poster board propped in a window or a sheet of office paper duct-taped to a desk or door, you are witnessing signs of failure—the failure to anticipate how people will actually use a space.

A well-designed building needs fewer signs than a poorly designed one. The front door looks like an entrance, and the bathroom is located where you might expect to find it. (In most restaurants, you can locate the restrooms without following an elaborate trail of arrows.) Receptionists and security staff are on the front lines of signage failure, forced to show the hordes of clueless wanderers where to find the elevator, the gift shop, or the ninth circle of hell. These harried gatekeepers often get exasperated with the public, yet the real object of their irritation should be the designers and middle managers responsible for their building’s signs and layout. Offered on the following pages are field notes on signage failure and signage solutions. EL

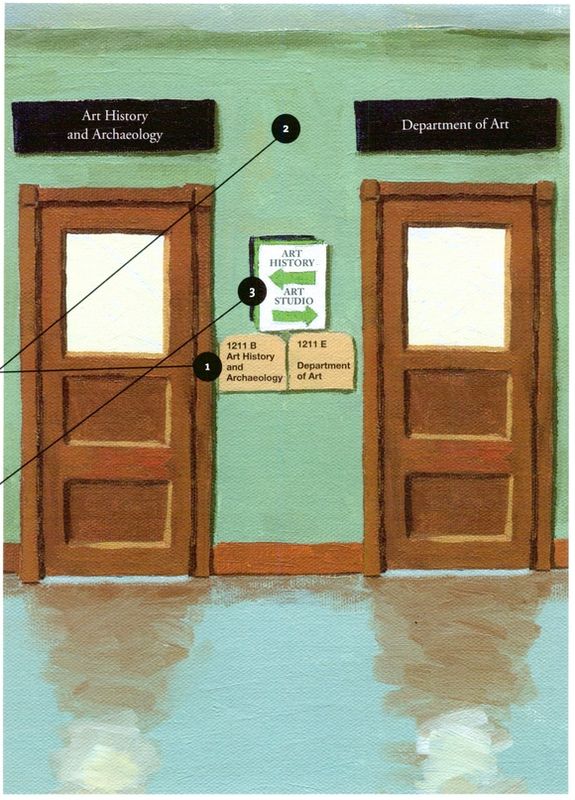

The image shown at right is reconstructed from a real office foyer at a large state university. Native informants (office workers at the school) explained to us the history of the three distinct phases of signage found on the site, all of which remain fully intact today. Thus preserved in time is an instructive tale of bureaucratic process, institutional pride, and fearless individual initiative. Look closely at your own environment, and you will see such stories all around you.

THE SITE The scene of our inquiry is the entrance area shared by two related yet distinct academic departments within the university. One department is called “Art History and Archaeology,” while the other is the “Department of Art.” The former is devoted to the scholarly study of civilization and its artifacts, while the latter is dedicated to hands-on studio practice.

PHASE ONE: THE PLASTICUS PLAQUE PERIOD Sometime in the 1980s, a campus-wide signage program was implemented by the Facilities division, who needed to assign official room numbers to every area of the school in order to respond to service calls. Made from modules of beige plastic, the plaques appear to have been ordered from a standard catalog—perhaps the same one from which Facilities orders toilet paper and floor polish. Placed low on the wall, these signs were commonly ignored by students and visitors, who tended to walk through the wrong door and then ask the staff inside where the hell they were.

PHASE TWO: THE BLACK-AND-WHITE PERIOD Towards the end of the twentieth century, the Chair of the Department of Art decided that “professional” signage was needed. Thus he decreed that two elegant black placards be installed above the doors, featuring large, classical lettering. Students and visitors ignored these signs as well.

PHASE THREE: THE DO-IT-YOURSELF PERIOD Finally, a courageous staff member, tired of rerouting confused persons, took matters into her own hands. She made a sign out of laminated office paper and backed it up with sheets of colored card stock for dramatic emphasis. Key to the success of this homely yet functional new sign are the in-your-face placement, the hard-to-miss arrows, and the simplified text (reworded to reflect the way students, faculty, and staff actually refer to the two departments). The new sign is not pretty, but it gets people where they need to go. Staff on the ground, forced to deal with confused folk on a day-to-day basis, are often inspired to produce low-tech but effective signs.

MISGUIDED: Three epochs in the life of a signage program

Among the most ubiquitous homemade signs are those in women’s bathrooms imploring us not to flush sanitary pads and tampons down the toilet. I often used to wonder, while sitting there doing my business in a public lavatory, “Who is it that actually does flush their monthlies down the toilet, causing needless hassle to shopkeepers and maintenance crews around the land? Don’t we all know better by now?” Then, one weekend the topic somehow came up with a female guest at my house. “Oh,” she said, “I always flush tampons down the toilet, just not pads.” Now I know the truth; all those signs—scrawled in Sharpie or computer-printed in Times New Roman—are for her.

When you need to discourage people from bumping their heads, missing their step, or peeing in your pool, what you need is a sign. Here are some tips on making temporary signs that look good and communicate clearly and calmly.

PLEASE DO NOT

FLUSH SANITARY

PADS, TAMPONS,

PAPER TOWELS,

CHEESE BURGERS,

HOT DOGS, OR

YESTERDAY’S

NEWSPAPER

DOWN THE TOILET.

FLUSH SANITARY

PADS, TAMPONS,

PAPER TOWELS,

CHEESE BURGERS,

HOT DOGS, OR

YESTERDAY’S

NEWSPAPER

DOWN THE TOILET.

HUGE ALL CAPS (you are crazy)

Please do not flush sanitary pads, tampons, paper towels, cheese burgers, hot dogs, or yesterday’s newspaper down the toilet.

MODERATELY-SIZED UPPER AND LOWER CASE (you are in control)

TYPOGRAPHY Be polite. You may be angry, disappointed, or ready to shoot the next clueless person who tries to flush their September Vogue down your toilet, but yelling at these people won’t make them behave better. Text written in all-capital letters makes you look frantic and out of control; try upper and lower case for a tone of confident, relaxed authority.

SIZE Homemade signs are usually printed on full sheets of 8.5-x-11-inch paper, because that’s what comes out of your office printer. But many signs will work just fine printed on half a sheet of paper or even less. Take a seat in your local bathroom stall. A bold sans serif typeface such as Helvetica will be highly legible from a short distance in sizes ranging from 14 to 18 points.

MASKING TAPE (you’re fired)

PICTURE FRAME (you’re hired)

Save the world.

Turn out the lights.

Turn out the lights.

TINY SIGN laminated with packing tape. This handy technique also works well for labeling storage bins.

MAKING AND INSTALLING SIGNS Plain paper signs are adequate in an emergency, but they hold up poorly over time. To create a more permanent sign, put your printout in a simple picture frame (very nice), mount it to foam bord (kind of nice), or laminate it with plastic (ugly, but you can wash it). Tiny signs can be laminated with clear packing tape.

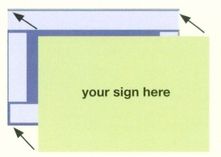

Signs are generally installed at eye level. Of course, eye levels vary from person to person; the standard dimension used in the United States is sixty inches from the floor, which accommodates people in wheel chairs. Sign companies can make many kinds of signs for you, from large-scale banners to adhesive vinyl letters and plaques in braille with raised text. For major projects, work with a professional designer—but stay involved, very involved.

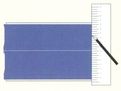

HOW TO TAPE A SIGN TO THE WALL (without ruining the wall)

1. In pencil, lightly trace around your sign on the surface where it will be installed.

2. Apply blue painter’s tape to the wall inside your pencil lines. (Painter’s tape won’t pull off the paint later.) With an X-Acto knife and a ruler, trim off the extra tape, leaving a neat blue rectangle that’s a hair smaller than your sign. Erase pencil lines.

3. Place strips of double-stick tape around the edges of the blue rectangle, and then carefully position the sign on top of the rectangle. Press firmly.

NOTE: If you don’t plan to be at your place of employment for long enough to see the sign removed, skip Step 2. But be warned: double-stick tape will seriously damage your paint job over time. This technique was developed for use in a major New York City art museum. It works.

SOFT SELL Personal feelings dominate social media.