THE SITES AT WAR

Sieges of early castles

As there are no written records from the Yayoi Period, any operational activity around the Yayoi stockades has to be inferred from the archaeological finds. The anti-invasion castles of Kyūshū , of course, never saw any action, and although the northern stockades were subjected to raiding by the emishi there is again a lack of any detailed written account of such operations. One account simply tells us: ‘They swarm like bees and gather like ants. … But when we attack, they flee into the mountains and forests. When we let them go, they assault our fortifications. … Each of their leaders is as good as 1,000 men.’

It is not until the Heian Period that we come across reliable contemporary accounts of operations involving fortifications, and here the source material is very rich. For good accounts of fighting around Heian Period stockades we need look no further than Mutsuwaki (Tale of Mutsu), the near-contemporary account of the Former Nine Years’ War. The first battle involving a stockade occurs at Komatsu:

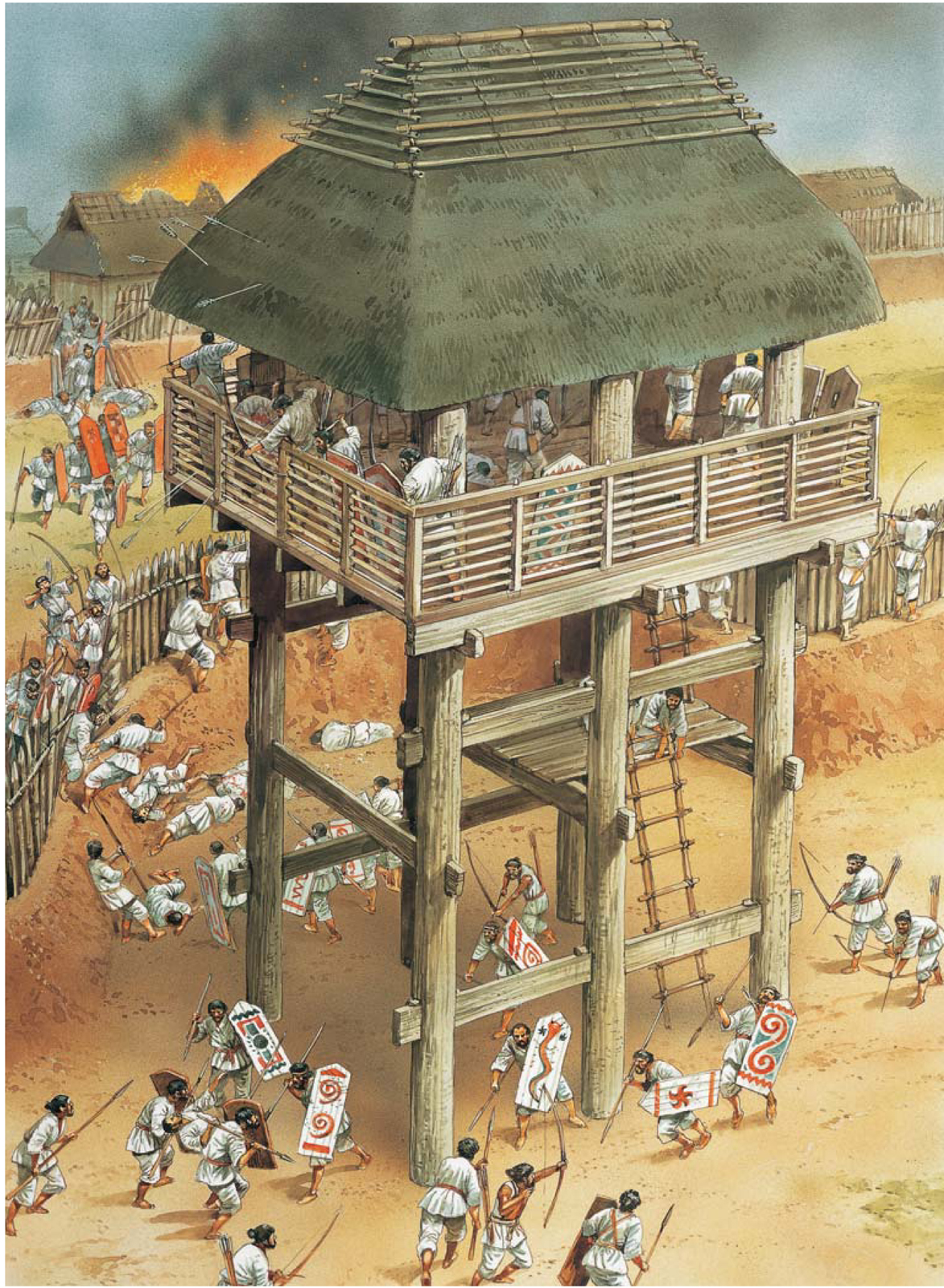

THE MOATED YAYOI SETTLEMENT OF YOSHINOGARI UNDER ATTACK: AD 250

THE MOATED YAYOI SETTLEMENT OF YOSHINOGARI UNDER ATTACK: AD 250

The Yayoi Period site of Yoshinogari has been thoroughly excavated and has revealed several defensive features. In this plate we see a hypothetical attack by a rival tribe on the Minami Naiku, the inner ‘palace’ to the south of the complex. The outer ditch has been thoroughly breached, and there is fierce fighting across the inner moat and palisade. The watchtower is playing an important role in the defence. The sources for the plate are the excavations and reconstructions at Yoshinogari.

At first both groups of attackers were held back by the deep blue waters that flowed beside the stockade on the east and the south, and by the mossy cliffs towering sheer above it on the north and the west. Presently, however, a band of 20 gallant men, led by two warriors named Fukae Korenori and Otomo Kazusue, began to chisel into the banks with their swords. They hauled themselves over the rocks with their spears, tunnelled underneath the stockade, and burst into the fortress with their weapons bared, to the utter confusion of the defenders.

The fight ended with the victorious army setting fire to the stockade. In the next siege section, which deals with the attack on Kuriyagawa, we first encounter the ōyumi, but the account is more notable for its stark savagery. The action is a far cry from the popular idea of a samurai battle, where elite fighters maintained the gentlemanly notion of giving challenges to honourable opponents. Instead the killing is completely anonymous, and when the attack is frustrated the besiegers resort to the indiscriminate weapon of fire: ‘When the enemy were far away, the defenders shot them to death with their ōyumi; when they were close, they struck them down with rocks. If by any chance someone reached the base of the fortress they cut him down with swords after scalding him with boiling water.’

The section continues to tell us how Yoriyoshi then prays to his family patron, Hachiman the god of war, to send a strong wind that will fan the flames he is about to ignite. He himself grasps the first torch, assuring his men that it is the will of the gods, and then tosses it on to the pyre. At the same instant a dove flew up from the neighbouring woods. As the dove was believed to be the messenger of Hachiman this is regarded as a very good omen. The god is placing his seal of approval on to the means whereby the battle will be ended.

In this section of the Later Three Years’ War scroll we see the conclusion of a siege by the burning down of the wooden buildings. Flames are pouring out of the loopholes in the plastered walls, which are resistant to fire. Samurai lie dead on the approaches to the castle.

An archery duel between besiegers and a tower of the Heian Period. Note the mon (family crest) on the wooden shields that provide extra defence. (Watanabe Museum, Tottori)

The little point of detail in the quotation that follows about the arrows stuck into the outside of the stockade acting as kindling gives the episode an air of great authenticity:

Yoriyoshi’s warriors crossed the river and attacked. In desperation several hundred rebels put on armour, brandished their swords, and tried to break through the cordon. Since they were resigned to death, they made no effort to protect themselves, and they had exacted a frightful toll from Yoriyoshi’s warriors before Takenori finally commanded, ‘let them through’. Once the encirclement was opened, they fled without a struggle. The besiegers then attacked their flanks and killed them all.

That was how sieges were conducted against the stockades of the Heian Period, with fire, cruelty and utter ruthlessness.

The sieges of the 14th century

The accounts in Taiheiki of the sieges of Akasaka and Chihaya during the Wars Between the Courts are very different in content from the harsh realism of the Mutsuwaki. The accent is very much on the skills and heroics of Kusunoki Masashige as he defends his fortresses using a mixture of bravery and cunning. At Akasaka an extra outer wall fools the attackers:

Akasaka eventually had to be abandoned when the besiegers cut off its water supply, so Kusunoki moved to the stronger and more remote castle of Chihaya. Its formidable appearance made the enemy cautious:

The defence of Chihaya Castle is dramatically illustrated by this relief model in the Kusunoki Masashige Memorial Museum at the Minatogawa Shrine in Kobe. The suspended rocks are released by cutting through the ropes, and a barrage of other stones accompanies them as the attackers are plunged down into the valley.

A stratagem appears shortly:

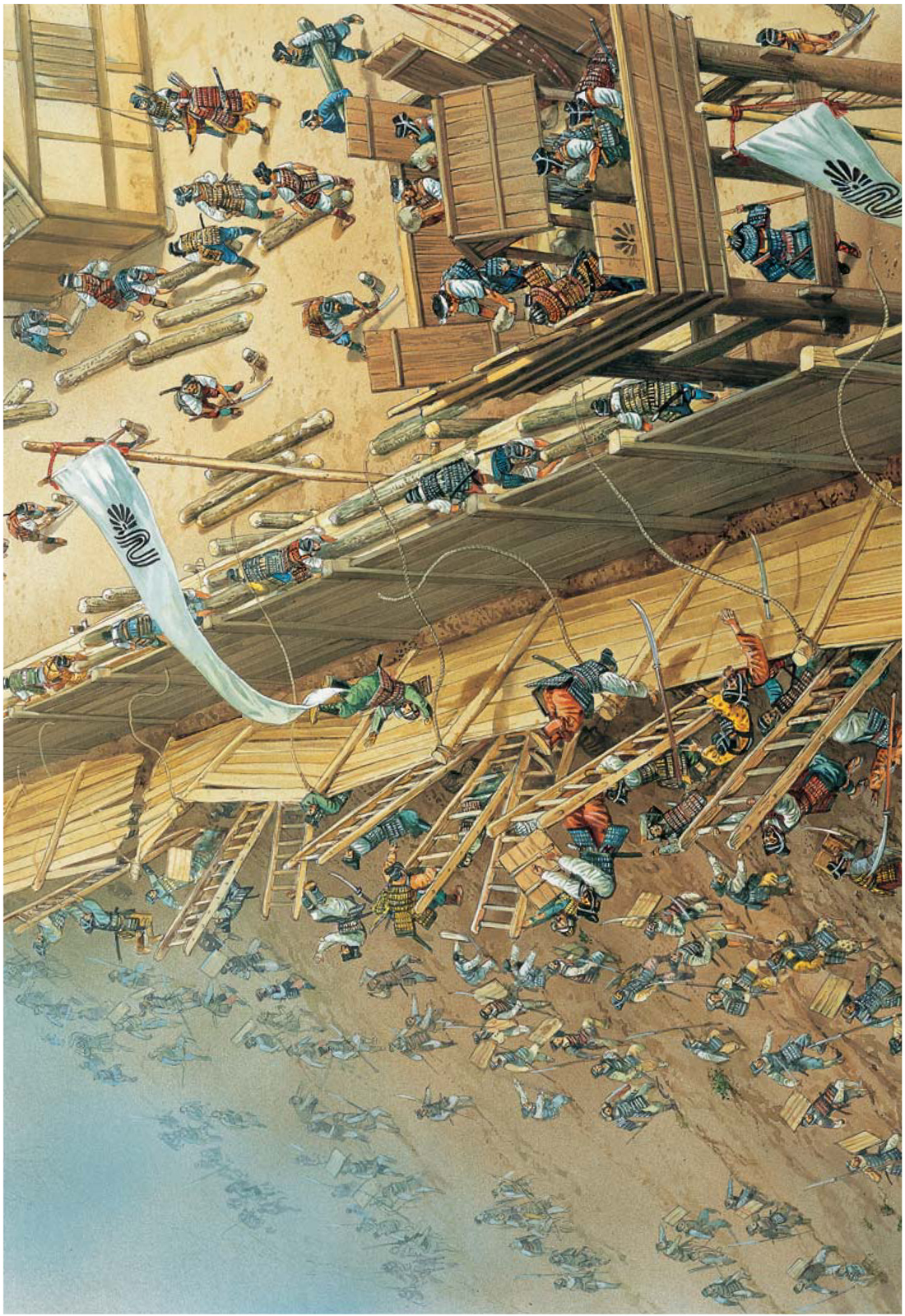

THE CASTLE OF AKASAKA UNDER ATTACK: 1333

THE CASTLE OF AKASAKA UNDER ATTACK: 1333

In this plate we see Kusunoki Masashige, the great imperial loyalist, putting into action one his celebrated stratagems in defence of Emperor Go Daigo. His men erected a dummy outer wall round Akasaka above one of its steepest slopes. As soon as the enemy were climbing up it the wall was allowed to collapse. The sources for this plate are the description of the action in the Taiheiki and research undertaken into contemporary castle design.

We also read of Kusunoki Masashige creating a dummy army of straw, and then releasing rocks by cutting ropes as the enemy drew near, and countering an equally ingenious ploy by the besiegers to create a bridge that could be dropped across one of the chasms. This was done by dropping combustible material on to the bridge and setting it on fire.

The siege of Arai Castle, 1516

The progress made by the Hōjō family from being obscure provincial daimyō to controlling the Kantō was carried out almost exclusively by conducting successful sieges against rival castles. The system of control by satellite castles followed on from these successes, with the Hōjō’s new possessions being defended against allcomers until the siege of Odawara in 1590. One of the most interesting accounts of a Hōjō acquisition of an enemy castle concerns the long war that Hōjō Sōun waged against the Miura family, which was carried out by a process of isolation and progressive control, and ended with a furious attack. The defeat of the Miura was essential if the Hōjō were to control the whole of Sagami Province and expand to the east, because the Miura controlled Okazaki Castle that overlooked the Tōkaidō road not far from Odawara castle, which had fallen to the Hōjō in 1495. They also had a number of outposts on the peninsula that bore their family name, which juts out into the sea further to the east and includes the former capital of Kamakura on its western shoreline.

The Miura were allied to the Ogigayatsu Uesugi, but their daimyō Miura Yoshiatsu’s failure to capture any Hōjō possessions and internal strife between the Ogigayatsu and Yamanouchi branches of the Uesugi allowed Hōjō Sōun to take the fight to the Miura, and in 1512 he captured Okazaki. Two months later he attacked Sumiyoshi Castle, which had once been part of the defences of Kamakura. This gave the Hōjō control of the old capital and drove the Miura back to their castle of Arai. The building of Tamanawa Castle to the north of the Miura Peninsula meant that the Miura were now surrounded.

Arai was located almost at the very end of the Miura Peninsula with rocky cliffs on nearly all sides of the castle site, which the Miura had made into an island by cutting a channel through the narrow isthmus than had joined it to the mainland. The only access to this artificial umijiro (sea castle) was a large wooden drawbridge that led to an open bailey beyond which lay the main castle. Hōjō Sōun believed that the Miura, now isolated in Arai, would ‘wither on the vine’ as the Hōjō Godaiki puts it, but the Miura were initially supremely confident, because they could be supplied from the sea by their own navy and had on the island what they described as a great cave known as the ‘thousand horsemen tower’ where large quantities of supplies could be stored. Four years later Sōun’s isolation of Arai appeared to have had no effect, so he decided to mount a decisive attack upon them in 1516.

Two thousand soldiers defended Arai, against whom Hōjō Sōun, who was now 84 years old, brought between 4,000 and 5,000 men. Once Sōun had cut Arai off from fresh supplies it did not take long for the 2,000 defenders to consume the rice intended for only 1,000 men. The final Hōjō assault involved a landing on one side of the island and a fight up a path while the main attack went against the channel under the drawbridge. Tons of rock and rubble were poured into the gap until it could be crossed, and then the Hōjō samurai fought their way up beneath the raised drawbridge.

Realizing that all was lost Miura Yoshiatsu and his son Yoshioki prepared to sell their lives dearly. It was a dark night because clouds obscured the moon. Father and son drank a final cup of sake together and led a furious charge out of the castle gate that smashed through the Hōjō lines to a depth of 200m. Young Yoshioki wielded an enormous iron-studded wooden club, until, entirely surrounded by enemies and unable to defend himself further, he performed the most dramatic act of suicide in Japanese history. If the story is to be believed, it was done by cutting off his own head. This greatly impressed the victorious Hōjō , who took the head back to Odawara and interred it under a pine tree.

THE MOATED YAYOI SETTLEMENT OF YOSHINOGARI UNDER ATTACK: AD 250

THE MOATED YAYOI SETTLEMENT OF YOSHINOGARI UNDER ATTACK: AD 250

THE CASTLE OF AKASAKA UNDER ATTACK: 1333

THE CASTLE OF AKASAKA UNDER ATTACK: 1333