She watches over the affairs of her household.

—PROVERBS 31:27

TO DO THIS MONTH:

□ Cook through Martha Stewart’s Cooking School (Proverbs 31:15; Titus 2:5)

□ Clean through Martha Stewart’s Homekeeping Handbook (Titus 2:5)

□ Host a dinner party (1 Peter 4:9; Hebrews 13:2)

□ Host Thanksgiving dinner (1 Peter 4:9)

I don’t know if I’ve mentioned this yet, but you can’t buy any sort of hard liquor in Rhea County, not even wine.

So when Martha Stewart’s braised short ribs called for an entire bottle of Côtes du Rhône, to be reduced about a million times into a “rich and unctuous sauce,” I was faced with the decision to either make the forty-five-minute drive to the nearest liquor store in Hamilton County or move on to the next recipe in Martha Stewart’s Cooking School—orange braised rabbit.

Rabbit? Now, where on earth was I going to get a rabbit?

Fortunately, Martha’s version of beef bourguignon, the French classic popularized in the States by the incomparable Julia Child, was Rhea County approved. Instead of burgundy, Martha’s “beef and stout stew” called for 16 ounces of Guinness, which you can easily pick up at the local Wal-Mart because local legislators don’t seem to mind if the county’s citizens get drunk on beer, so long as it’s not on Sunday.

The fact that Martha’s beef stew recipe appeared complicated yet doable was just one reason I chose her as my guide through a month of domesticity. The elevation of homemaking as a woman’s highest calling is such a critical centerpiece to the modern biblical womanhood movement, I figured no one less than the Domestic Diva herself would do. Besides, you have to admire a woman who can build an empire on crafts and apple pie, know enough about trading to commit securities fraud, go to jail for five months, and then come right back to cooking soufflés and decorating gourds on TV as if nothing had happened, casually mentioning that she learned this or that knitting pattern “at Alderson,” like federal prison was just another Bedford or Skylands.

Furthermore, I loved poring over the pages of Martha Stewart’s Cooking School and Martha Stewart’s Homekeeping Handbook because they read like textbooks.

“This book has been designed and written as a course of study,” Martha explains in the introduction to Cooking School, “very much like a college course in chemistry, which requires the student to master the basics before performing more advanced experiments.”1

She takes the same approach in Homekeeping: “Consider the ’Throughout the House’ section of the book as a master class on how to clean,” she wrote. “Here you will find simple, clear instructions for the basic techniques needed to clean any household object or surface. The five fundamentals—dusting, wiping up, sweeping, vacuuming, and mopping—that constitute the core of any weekly household schedule are covered in ‘Routine Cleaning,’ with detailed descriptions of the best tools and equipment for each task.”2

Martha didn’t assume I knew what I was doing, but she didn’t talk down to me either. A lot of women absorb their homemaking skills through osmosis, watching their mothers and grandmothers over the years, taking mental notes along the way. Not me. The perpetual student, I require a book and highlighter. Martha’s array of charts and photographs, sidebars and endnotes felt familiar and calming to me. I could study detailed, step-by-step illustrations on how to bone a leg of lamb or polish silver, gaze at beautiful pictures of brightly colored soup garnishes and herbs set against pristine white backgrounds, and learn all about the science of bleach, the secret of poaching, and the history of bouillabaisse. Martha even includes “extra credit” sections at the end of each chapter for overachievers like me. All I’d have to do is whip up a little compound butter here and lemon curd there, and I’d be a regular Julie Powell in no time.

I just hoped my efforts would be domestic enough.

The importance of homemaking in the contemporary biblical womanhood movement cannot be overstated, and proponents tend to use strong, unequivocal language to argue that the only sphere in which a woman can truly bring glory to God is the home. This position is based primarily on an idealized elevation of the post–industrial revolution nuclear family rather than biblical culture, but proponents point to two passages of Scripture to make their case.

Proverbs 31:10–31, which, among other things, extols the domestic accomplishments of an upper-class Jewish wife, and Titus 2:4–5, in which the older women of Crete are encouraged by the apostle Paul to teach younger women to “love their husbands and children, to be self-controlled and pure, and to be busy at home” (emphasis added).3

Dorothy Patterson, in chapter 22 of Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, concludes from these two passages that “keeping the home is God’s assignment to the wife—even down to changing the sheets, doing the laundry, and scrubbing the floors.” Ambitions that might lead a woman to work outside the home, says Patterson, constitute the kind of “evil desires” that lead directly to sin.4

Debi Pearl, author of Created to Be His Help Meet, wrote, “A young mother’s place is in the home, keeping it, guarding it, watching over those entrusted to her. To do otherwise will surely cause the Word of God to be blasphemed. Even if you could disobey God and it not produce visible ill consequences, it would only prove that God is long-suffering . . . but the judgment will assuredly come.”5

“Quite simply, there is no such thing as ‘Christian feminism,’ ” explains Stacy McDonald in a book titled Passionate Housewives Desperate for God. “We either embrace the biblical model . . . or we reject it and plummet over the cliff with the rest of the passengers on the railcar.”6

All this talk of judgment and damnation and runaway railcars made me wonder how these ladies would feel knowing I’d chosen an ex-con for a teacher, was secretly squeezing a few business trips into my schedule, and had every intention of stocking up on liquor each time I crossed the county line . . . for the braised ribs, of course. Perhaps the real reason I’d chosen Martha Stewart to accompany me on this leg of the journey was the fact that her drive, intelligence, and unapologetic ambition allowed me to preserve some small part of myself as I ventured into a world that didn’t yet feel my own.

Sure, Martha can be a real stickler for doing things her way, but you don’t hear her saying that you’ll go to hell if you don’t.

The wise woman builds her house, But the foolish tears it down with her own hands.

—PROVERBS 14:1 NASB

Besides the fact that we were eating dinner at about nine thirty every night, the first week of cooking went well. I started with soups, because according to Martha, “the measure of a good cook is how well he or she makes soup. Not a complicated, multicourse meal or a delicate soufflé, but a simple soup.”7

I’m not so sure I’d use the word simple, seeing as how Martha’s basic chicken soup took me over three hours to make. This was mostly my fault, of course. Tearing a whole chicken into bite-size pieces requires that a girl get rather intimate with her meat, and I hate getting intimate with my meat. Wiggling those fleshy little legs until they separated from the joint made me feel like some kind of animal. Not even a pair of rubber gloves, two feet of distance, and closed eyes could convince me that I was doing anything but handling a carcass.

“How do you like the parsnips?” I asked as Dan took his first sip of soup that night.

“They’re good.”

“I’ve never cooked with them before. I didn’t even know what they looked like until yesterday.”

“Hmmm.”

“They look kinda like seasick carrots, in case you’re wondering. How do you like the chicken?”

“It’s good.”

“I used free range organic-fed chicken so we don’t have to feel guilty. Do you think the pieces are too small?

“No. They’re good.”

“It tastes fresh, doesn’t it? It smells fresh, too, like you can tell it’s homemade.”

“Yeah. It’s good.”

“Good grief, Dan. Could you please use a word besides good? How do you really feel about this soup? Tell me the truth.”

Dan looked trapped.

“How do I feel about the soup?”

“It’s watery and bland because I used water instead of stock. That’s what you’re thinking.”

“Well, maybe a little, but overall it’s . . . it’s just good, okay? That’s the best word I can come up with. I’m sorry I don’t have a fancy vocabulary like you.”

I let it go, mostly on account of the vocabulary compliment. Besides, it was nearly 10 p.m., and I hadn’t started the dishes or decided whether to start the stock that night or the next morning. There’s no time for arguing when you’ve just realized a mangled chicken carcass has been sitting out on your counter for an hour.

Fortunately, the rest of the week’s meals conjured some better adjectives from the other side of the dining room table. Among our favorites were Martha’s savory French toast BLT, Martha’s roasted autumn harvest salad, and Martha’s beef and stout stew.

The project had revealed its first truly surprising result: I enjoyed cooking. In the four hours it took me to prepare that beef and stout stew, I forgot about all the loose ends and screwups and unreturned e-mails in my life and instead concentrated all my scattered energy like a magnifying lens into one hot beam of unadulterated intention—chopping and mincing, browning and frying, grating and blanching, and stirring and boiling. Even when dinner didn’t turn out perfectly, I found the process itself rewarding.

The first week of domestication would have gone down in the books as an indisputable success, were it not for all the housework.

My robust lexicon notwithstanding, I struggle to find the right words to describe just how much I despise, hate, abhor, revile, detest, and categorically abominate anything to do with home maintenance. While cooking strikes me as an essentially creative act, cleaning seems little more than an exercise in decay management, enough to trigger an existential crisis each time the ring around the toilet bowl reappears.

Now, don’t get me wrong; I like things to be clean. It’s not as though Dan and I “live in squalor,” as my mom likes to say. But each time the laundry basket starts to overflow or the fridge gets crowded with old leftovers, I put up a fight. And when I’m not in the mood for a fight, I just sit around and feel guilty about it.

In a matter of days, The Martha Stewart Homekeeping Handbook had turned this little complex of mine into full-blown neurosis. It started with the checklists—Martha’s list of “to-dos” for every day, every week, every month, and every season. These would have been helpful guides had they not revealed what a complete and utter failure I am at everything I attempt. As it turns out, until I started this experiment, pretty much everything on Martha’s “clean every day” list I did about once a week, pretty much everything on Martha’s “clean every week” list I did about once a month, pretty much everything on Martha’s “clean every month” list I did about once a year, and pretty much everything on Martha’s “clean every season” list I’d never done in my life. That’s right, folks; I’d never vacuumed our refrigerator grille and coil. We lived in squalor after all.

After trying and failing to cross every item off Martha’s to-do lists, I decided to conduct a room-by-room deep-clean of the house, starting with the kitchen. According to Martha, “it’s the room with more home concerns than any other.”8

This was certainly true in our house. When we first purchased the house seven years ago, I made a big stink about replacing the old maple cabinets and mustard-yellow countertops, but I guess one can grow accustomed to cooking in a veritable cave when, by the grace of God, it includes a gas stove. Working with less than seven feet of counter space and no pantry, I’d assembled a motley crew of add-ons, including a wobbly folding table, a kid’s writing desk, and a hideous microwave stand that a retired missionary was getting rid of, which really tells you something.

According to Martha, “it’s not the amount of room you have that matters, but how you manage it.” With most of my counter space cluttered with appliances and cereal boxes, and with cabinets so disheveled that finding the lid to the stockpot required spelunking experience, it was clear that I wasn’t using my space as efficiently as possible, a problem I needed to solve before tackling something as involved as beef bourguignon.

So I took everything out—pots, pans, dishes, stemware, cutting boards, appliances canisters, pottery, platters, soup cans, cake stands, measuring cups, and muffin pans—piled it all in the dining room, and stood in my empty kitchen for two hours until I knew exactly where everything had to go.

Mom did this every now and then when we were kids. She’d put a Carole King tape in the stereo, empty all the drawers and cabinets in the kitchen, and clean the whole thing top to bottom while singing at the top of her lungs about the earth moving under her feet and the sky tumbling down, a-tumbling down. Amanda and I watched, bewildered, among the stockpots and frying pans. Shouting above the music, she told us, “It has to get messy before it gets clean”—a philosophy that pretty much sums up every meaningful experience of my life, from homemaking to friendships to faith. Sometimes you’ve just got to tear everything out, expose all the innards, and start over again.

Sure enough, cooking is a lot more fun when you’re not at war with your kitchen. As much as I hate to admit it, the sixteen hours I spent deep-cleaning my kitchen turned out to be some of the most valuable hours of the project. The task required creativity, problem solving, innovation, and resourcefulness, and it forced me to confront the ugly air of condescension that permeated my attitude toward homemaking. It was out of ignorance and insecurity that I ever looked down my nose at women who make homemaking their full-time occupation.

I got so confident, in fact, I did something I’d have never dreamed of doing before: I called Mom and officially invited the whole family to our house for Thanksgiving dinner.

When Brother Lawrence sought sanctuary from the tumults of seventeenth-century France, he entered a Carmelite monastery in Paris, where his lack of education relegated him to kitchen duty. Charged with tending to the abbey’s most mundane chores, Brother Lawrence nevertheless earned a reputation among his fellow monks for exuding a contagious sense of joy and peace as he went about his work—so much so that after his death, they compiled the few maxims and letters and interviews he left behind into a work that would become a classic Christian text: The Practice of the Presence of God.

“The time of business,” explained Brother Lawrence, “does not with me differ from the time of prayer; and in the noise and clatter of my kitchen, while several persons are at the same time calling for different things, I possess God in as great tranquility as if I were upon my knees at the blessed sacrament.”9

For Brother Lawrence, God’s presence permeated everything—from the pots and pans in the kitchen sink to the water and soap that washed them. Every act of faithfulness in these small tasks communicated his love for God and desire to live in perpetual worship. “It is enough for me to pick up but a straw from the ground for the love of God,” he said.10

After reading Brother Lawrence, I tried to go about my housework with a little more mindfulness—listening to each rhythmic swishing of the broom, feeling the warm water rush down my arm and off my fingers as I scrubbed potatoes, savoring the scent of clean laundry fresh out of the dryer, delighting in the sight of all the colorful herbs and vegetables and cheeses on my countertop. And sure enough, I found myself connecting to that same presence that I encountered during contemplative prayer, the presence that reminded me that the roots of my spirit extended deep into the ground. I got less done when I worked with mindfulness, but, somehow, I felt more in control.

I get the sense that many in the contemporary biblical womanhood movement feel that the tasks associated with homemaking have been so marginalized in our culture that it’s up to them to restore the sacredness of keeping the home. This is a noble goal indeed, and one around which all people of faith can rally. But in our efforts to celebrate and affirm God’s presence in the home, we should be wary of elevating the vocation of homemaking above all others by insinuating that for women, God’s presence is somehow restricted to that sphere.

If God is the God of all pots and pans, then He is also the God of all shovels and computers and paints and assembly lines and executive offices and classrooms. Peace and joy belong not to the woman who finds the right vocation, but to the woman who finds God in any vocation, who looks for the divine around every corner.

As Elizabeth Barret Browning famously put it:

Earth’s crammed with heaven,

And every common bush afire with God,

But only he who sees takes off his shoes;

The rest sit round it and pluck blackberries.

Faith’s not about finding the right bush. It’s about taking off your shoes.

Offer hospitality to one another without grumbling.

—1 PE.3TER 4:9

It’s a good thing I retired the Jar of Contention at the end of October or else it would have been fully restocked at the conclusion of November 8.

Up until this point, Dan had been the only witness to my culinary exploits. This seemed rather “unbiblical” to me, considering the fact that hospitality is such a celebrated virtue in Scripture. So on November 8, I invited the Falzone family (yep, rhymes with “calzone”) over for a dinner of stuffed shells. Dayna had recently announced that Baby #3 was on his or her way, so it seemed as good a time as any to get together and celebrate.

I found the stuffed shells recipe in November’s edition of Martha Stewart Living, and it looked easy enough: boxed jumbo shells stuffed with ricotta, radicchio, and prosciutto, baked in homemade or (gasp!) store-bought tomato sauce, and topped with butter, mozzarella, and parmesan—served with salad and bread. Arteries and blood pressure be darned, I could handle that.

It didn’t occur to me until I was halfway to the grocery store that cooking stuffed shells for an Italian might not be the best idea. A Falzone probably has, you know, standards regarding his pasta. And if that weren’t enough, I decided to go ahead and purchase all the ingredients for Martha’s beef and stout stew that same day, which gave me a grocery list that came to three pages, typed and single-spaced, whose contents included unfamiliar items like cipollini onions, cremini mushrooms, slab bacon, and horseradish root, three of which proved wholly unavailable to residents of Rhea County.

Which brings me to a point I’ve been meaning to make for a while now—Martha Stewart hates rural America.

Well, that might not be entirely true, but I can say from experience that nothing makes a rural Tennessean feel precisely like a rural Tennessean than a list of ingredients that cannot be found within a thirty-mile radius of one’s home. “Ask your butcher,” says Martha. Or, “Talk with your fishmonger,” says Martha. “Visit your Asian market,” says Martha. “Try your local gourmet food purveyor,” says Martha.

I’m tempted to remind Martha that not all of us have personal fishmongers, butchers, and stockbrokers to “tell us these things.”

Of course, the upside to being strapped with an exotic grocery list is that I get to feel all superior whenever I walk into Wal-Mart or BI-LO with requests that make the produce guys scratch their heads. Around here, asking for arugula or chanterelles turns you into a regular foodie, as such delicacies must be specially ordered from Chattanooga or Atlanta. I admit to experiencing a touch of blithe satisfaction when the checkout clerk looked at my horseradish root and asked, “You mean to tell me you’re gonna eat that?”

“Grate it, actually,” I said, as if I knew what the heck I was doing.

That day it was the cipollini onions that threw everyone off. I started at Wal-Mart, where my friend Amber from frozen foods helped me find the produce guy, who helped me find the produce manager, who helped me find the store manager—none of whom had ever even heard of cipollini onions. Next thing I knew, a confluence of workers, managers, and fellow shoppers had assembled around me in the potato aisle, passing around my grocery list like it was an out-of-towner’s bad directions.

“It’s really not a big deal,” I told the produce manager, a little embarrassed by all the attention I’d garnered. “It’s a Martha Stewart recipe, so there’s always some unattainable ingredient involved.”

A forty-something with a wide girth, shoulder-length blond hair, and thick East Tennessee drawl, the produce manager seemed perfectly satisfied with that explanation.

“Yeah, I’d say she done put them in there just to throw you off,” he concluded.

Just to throw me off. That sounded about right.

It was six o’clock when I finished cooking the prosciutto, radicchio, garlic, and onion and started stuffing the shells. We expected Tony and Dayna and the girls around six thirty. The bathroom hadn’t been cleaned yet, so we may as well have been running around naked. I started rummaging through the cabinets, dramatically banging together pots and pans and releasing long, loud sighs in an attempt to coax Dan into the kitchen to see if he could help. Normally I would just ask, but we’d been trying to stick to traditional roles in deference to the project, which to the credit of the biblical womanhood advocates had resulted in a lot fewer arguments about division of labor. But as the clock ticked away and the jar of tomato sauce proved impossible to open, a fresh wave of resentment rolled over me.

“Can’t you tell that I’m struggling in here?” I yelled.

After about a minute, Dan appeared around the corner.

“Yeah, but aren’t you supposed to do this stuff by yourself? You know, for the project?”

I knew he wasn’t taking advantage of the situation, just trying to preserve the integrity of the project, because Dan’s big into integrity.

“You’re just taking advantage of the situation,” I wailed.

“Hon, you know that’s not true. I’d be happy to help you.”

“Well then, why don’t you volunteer?”

“I didn’t know that was allowed.”

“OF COURSE it’s allowed! No one said you can’t initiate assistance to your wife when she’s struggling.”

“Okay. So what can I do?”

This felt wrong. As much as I wanted Dan’s help and pity, bossing him around and turning him into the bad guy didn’t honor the experiment or our relationship.

“Maybe you could just call Tony and Dayna and tell them to come at seven instead. I’ll take care of everything else.”

He let me bury my head in his chest and cry for a few minutes, leaving two distinct mascara marks on his white T-shirt. Sometimes, when I’m separating the laundry after a tough week, I find two or three similarly stained undershirts and I’m reminded of why I married this man.

Tony and Dayna arrived right at seven, just as the shells turned golden and the sauce bubbly. Dayna, who had been kind enough to bring a dessert of apple turnovers, innocently asked how the project had affected my workout routine, which, along with my aching feet, put me in a bit of a funk for the rest of the night, even though everyone seemed to enjoy the meal.

It wasn’t until after dessert, as I faced a mountain of dishes alone in the kitchen, that I realized how much Addy and Aury, the little Falzones, were enjoying themselves. They’d asked me to turn up the music—Amy Winehouse, if you must know—and were dancing around and around the dining room table, giggling and waving their red paper napkins in the air like Bulgarian folk dancers. (Well, Aury was mostly lumbering and falling, as she was only two at the time.)

“Will you dance with us?” Addy asked, after the sound of a particularly raucous fall brought me around the corner to check on them.

“Well, okay.”

So the three of us held hands and danced around the table to “Trouble,” the scent of garlic and prosciutto still hanging in the air and the dishes still piled high in the kitchen.

Suddenly I remembered a mysterious verse from the book of Hebrews.

“Do not forget to entertain strangers, for by so doing some have unwittingly entertained angels” (13:2 NKJV).

Martha—not the one in my cookbook, but the one in the Bible—was one of Jesus’ closest friends and disciples. According to the gospels of Luke and John, she opened her home to Him, shared meals with Him, and stood by His side as He raised her brother, Lazarus, from the dead. John reports that “Jesus loved Martha and her sister and Lazarus” (John 11:5). That Martha’s name appears before her brother’s suggests that this woman garnered considerable respect among the earliest followers of Jesus.

Despite her esteemed status, poor Martha is best known today for a less-than-flattering incident involving her sister, Mary. As the story goes, Jesus and some of His followers were traveling through the town of Bethany, where “Martha opened her home to [them]” (Luke 10:38), serving food and offering shelter for the night. Since sudden overnight company is the leading cause of insanity among women, Martha got a little stressed out with all the preparations that go into hosting a troupe of tired, hungry, first-century Jewish men for the weekend. Perhaps after attempting to grate some horseradish, she charged into the next room, where Mary sat at the feet of Jesus, listening to His teachings.

“Lord, don’t you care that my sister has left me to do the work by myself?” Martha demands. “Tell her to help me!” (V. 40).

Folks were always asking Jesus to intervene in family disputes and other seemingly trivial matters. You would think this would have irritated Him, being God-in-flesh and all, but His response to Martha was gentle, almost tender.

“Martha, Martha,” he said, “you are worried and upset about many things, but few things are needed—or indeed only one. Mary has chosen what is better, and it will not be taken away from her” (VV. 41–42 UPDATED NIV).

The Precious Moments New King James Version of the Bible that I toted around to Sunday school as a child included a cartoon illustration of this story that depicted Mary kneeling at the feet of Jesus, looking quite like the Virgin herself, with hands clasped together in prayer, body positioned at a perfect ninety-degree angle, eyes closed, and head covered, while Martha, looking rather like a Disney stepsister, with an enormous nose, angular jaw, and kooky hairdo, cast an exaggerated glare at her sister while balancing a platter of grapes in her hands—a sharp contrast between the servant and the student, considering the fact that good Christian girls are generally expected to be both.

Feminists like me love this story. Here we have Jesus gladly teaching a woman who was bold enough to study under a rabbi, which was patently condemned at the time. However, conservatives note that Martha served future meals to Jesus and His disciples, suggesting that Jesus called Martha out on her critical attitude, not her role as a homemaker. As tempting as it is to cast Mary and Martha as flat, lifeless foils of each other—cartoonish representations of our rival callings as women—I think that misses the point.

Martha certainly wasn’t the first and she won’t be the last to dismiss someone else’s encounter with God because it didn’t fit the mold. When an unnamed woman interrupted a meal to anoint Jesus’ feet with an expensive perfume, some of those present complained that the money could have been donated to the poor (Matthew 26:6–13; Mark 14:3–9). When an invalid healed by Jesus ran through the streets, carrying the mat to which he had been confined for thirty-eight years, a group of religious leaders chastised him for lifting something heavy on the Sabbath ( John 5). When my friend Jackie became the first woman to deliver a sermon from the pulpit of a megachurch in Dallas, she received hate mail from fellow Christians. When a new mom told me she felt closer to God since giving birth, I secretly dismissed her feelings as hormone-induced sentimentalism.

I guess we’re all a little afraid that if God’s presence is there, it cannot be here.

Caring for the poor, resting on the Sabbath, showing hospitality and keeping the home—these are important things that can lead us to God, but God is not contained in them. The gentle Rabbi reminds us that few things really matter and only one thing is necessary.

Mary found it outside the bounds of her expected duties as a woman, and no amount of criticism or questioning could take it away from her. Martha found it in the gentle reminder to slow down, let go, and be careful of challenging another woman’s choices, for you never know when she may be sitting at the feet of God.

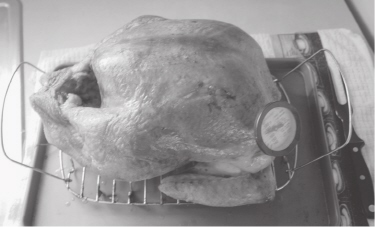

It’s safe to say that every cook will be called upon to roast a turkey at some point in his or her life.11

—MARTHA STEWART

I suppose it’s not a good sign when your copy of Good Housekeeping is stuck to the bathroom floor, covered in hair, toenail clippings, and dust bunnies, but by mid-November I’d gotten so good at cooking I figured God and Martha would cut me some slack on the cleaning front.

Since completing the beef stew, I’d moved on to desserts, popping chocolate chip cookies, cheesecake, and crème brûlée out of the oven like I was born with oven mitts on my hands.

Unfortunately, my dessert domination came to a fateful end the night before Thanksgiving when I attempted Martha Stewart’s double-crusted apple pie. It had already been an intense week, what

with a twenty-four-pound turkey to thaw, groceries to buy, centerpieces to assemble, and an apparently monumental decision to make about whether or not to brine. (I’d reveal my final verdict, but it appears this would turn 50 percent of the population against me.) Now with less than eight hours before my alarm was set to go off the next morning, I found myself on the kitchen floor, crying and cursing and shaking flecks of pâte brisée (French for “pie crust”) out of my hair.

(Going into this project, I was determined to avoid the whole crumple-to-the-kitchen-floor-in-a-heap-of-sobs bit, as it’s getting a tad cliché, don’t you think? So I feel it’s important to note that I didn’t crumple to the kitchen floor in a heap of sobs; I just happened to be sitting on the kitchen floor when I started to cry.)

The evening had gone so well up to that point. My friend Carrie, who would be joining us for Thanksgiving dinner, let me borrow her apple peeler—an industrious little contraption that made me feel like Laura Ingalls Wilder as I cranked the iron lever to neatly core, cut, and peel ten Granny Smiths, their cool juices spraying all over my arms like sawdust from a circular. The peels came out in sweet-smelling coils that I munched on as I read Martha’s instructions for preparing the pâte brisée.

“Perhaps because of the risk of overworking,” says Martha, “and turning out something that tears in two or tastes more leaden than light, many home cooks shy away from homemade dough, opting instead for unfold-as-you-go boxed crusts.”12

Losers.

“But making perfect pie dough from scratch should be part of any home cook’s basic skills. And the best dough for homemade pies is pâte brisée . . . Getting the right proportion of butter to flour is crucial, as is using very cold ingredients and a light hand.”

Bring it, Martha.

I confess that part of my motivation for tackling homemade apple pie the night before Thanksgiving dinner was the fact that my mother had advised against it.

“At least use a frozen pie crust,” she said. “Why put all this extra stress on yourself?”

But I’d grown overconfident, so the fact that I’d never in my life used a pastry blender or a rolling pin didn’t stop me from going right ahead and whisking together some flour, sugar, and salt, cutting in two sticks of butter, adding some water, and then kneading it all together to form two disks that looked exactly like the picture on page 438, thank you very much. Then I wrapped my pâte brisée in plastic and put it in the refrigerator while I combined my (slightly browning) apples with sugar, flour, lemon juice, cinnamon, ginger, and salt.

A taste test proved I was on the right track.

“Assemble the pie,” commanded the directions.

No problem.

I dusted the counter with flour, placed the first pâte brisée on the surface, took out my rolling pin, and began my slow break from sanity. To this day I am convinced that rendering that lump of dough into a crust that is precisely one-eighth of an inch thick and thirteen inches in diameter would require Douglas Adams–style rematerialization. I did everything the book told me to do. I rolled the dough from the center out to the edges. I turned it as I went along. I tried using parchment paper. But after thirty minutes of excruciating tedium, I decided that eleven inches in diameter would have to do. I unrolled the paper-thin dough into the pie pan, where it barely peeked over the edges, filled it with the apple mixture, wrestled again with the second round of pâte brisée, and then finally draped the “lid” over the filling.

“Use kitchen shears to trim overhang of both crusts to 1-inch,” said Martha.

Well, I can safely skip that step.

“Press edges to seal.”

Okay.

“Fold overhang under, and crimp edges: With thumb and index finger of one hand, gently press dough against index finger of other hand. Continue around pie.”

This proved challenging given the amount of crust I had to work worth, but by the time I finished, it didn’t look half-bad, almost like Martha’s picture, in fact.

And then I realized I’d forgotten to add the butter to the filling.

Crap.

I immediately got on my phone to tweet about the predicament and solicit advice. Of the dozen or so friends who were online at 9 p.m. the night before Thanksgiving—most of them men—three suggested that I cut the butter into little slivers and stick it through the air slits, which turned out to be a good idea except that my air slits ended up looking more like giant gashes through which butter was bleeding out of my pie.

“Whisk egg yolk and cream in a bowl; brush over top crust,” instructed Martha. “If desired, use cutters to cut chilled scraps into leaves or other shapes; adhere to top of crust with egg wash. This is a good way to hide imperfections.”

“Sprinkle with sanding sugar.”

Sanding sugar, I could only assume, was powdered sugar finely sieved. So I decided to try out a little trick I saw in Martha Stewart Living—a “good thing” as she likes to call it. I took my half-gallon canister of powdered sugar, covered the opening with cheesecloth, held it over the pie, and shook.

Almost instantly the cheesecloth fell through, releasing an avalanche of powdered sugar onto my butter-bleeding pie.

This is when I decided to sit down for a while.

Dan had the good sense to be at a friend’s house, playing Halo that night, so I wallowed alone in self-pity for a while before rousing myself to take a picture of the sugar-doused pie with my phone, tweet about the fiasco, and soak in the sympathy of my readers. Further inspection revealed that just one side of the pie caught the brunt of the disaster, so I began shoveling, first with a measuring cup, then with a spoon, and finally with a butter knife. When I finished, a thin layer of sugar remained, which promptly burned in the oven. Five hours before I was to put a twenty-four-pound turkey in, I pulled a charred, lacerated, butter-bleeding shadow of a pie out.

Icarus had flown too close to the sun.

That night I dreamed about giblets and gravy, and as often happens when I’m so rudely confronted with my inadequacies as a woman, babies. At some point Dan came home and asked if something was burning.

At 5:30 a.m. the alarm sounded, and I lumbered back into the dark kitchen to make some coffee and turn to page 149 of Martha Stewart’s Cooking School, where the recipe for “Perfect Roast Turkey” slowly sharpened into focus.

I’d been warned about a million times to remember to take out the giblets, so I heaved the bird out of the refrigerator, placed it on top of a bed of paper towels to sop up all the nasty pink juices, pulled on some rubber gloves, and reluctantly began my day with my hand in a turkey’s orifice. Talk about getting intimate with your meat.

Just as expected, I found the plastic bag of giblets nestled inside the chest cavity, but there was something else rattling around in there I wasn’t so sure about, some kind of bone. The package instructions seem to suggest it was the poor gal’s neck, but I called the Butterball Turkey Talk-Line just to be sure.

The Turkey Talk-Line was busy, probably because 6:00 a.m. on Thanksgiving morning is about the time most of us first-timers realize what we’ve gotten ourselves into. Fortunately, the menu included on option to listen to Betty or somebody talk about how to prepare a turkey, and I distinctly heard her say to remove the giblets and neck. So I pulled out the neck, ignored Martha’s instructions to reserve the offal for gravy, and threw it with the giblets into the garbage. (We Southern girls make our gravy out of grease, not body parts.) I prepared my basting liquid, seasoned the cavity, lathered the bird in butter, and placed it in the roasting pan.

But something didn’t look right. The poor thing appeared to be attempting flight.

I read back through Martha’s instructions to see “fold wing tips under.”

This proved to be the hardest part of the whole process because apparently I’m so weak I can’t even arm wrestle a dead turkey, but also because the rest of the day went . . . well . . . perfectly.

My parents came over, along with our pastor, Brian; his wife,

Carrie; and their two young daughters, Avery and Adi. Carrie brought a pumpkin pie and banana pudding, so we didn’t have to eat my butter-bleeding apple pie. The table looked beautiful, all the food came out on time, the turkey was tender and juicy, and the conversation was fantastic.

Everything went so perfectly I started to annoy myself.

How am I supposed to get any writing material out of this?

Or maybe it was my definition of “perfect” that had changed. Somewhere between the chicken soup and the butter-bleeding pie, I’d made peace with the God of pots and pans—not because God wanted to meet me in the kitchen, but because He wanted to meet me everywhere, in all things, big or small. Knowing that God both inhabits and transcends our daily vocations, no matter how glorious or mundane, should be enough to unite all women of faith and end that nasty cycle of judgment we get caught in these days.

Mom and Carrie helped me with the dishes. Brian volunteered to pick apart the carcass. Avery and Adi learned to play “Living on the Edge” on Guitar Hero with Dan and Dad.

Finally, after the company was gone, the dishes done, and the leftovers distributed, I sank into the living room couch with a glass of rosé and offered up a silent toast—to Mary, Martha, and me.

READ MORE:

“Is Voting ‘Biblical’?”— http://rachelheldevans.com/votingbiblical

“Beef and Stout Stew”— http://rachelheldevans.com/beet-stew