Chapter Seven

The Changing Family

7.1 Introduction

The great demographic shift ushered in fundamental changes that were both causes and consequences of changes in the well-being of individuals and families. In Part Two we considered the quantitative dimensions of population change: the increasing numbers, the extension of life and the like. In this part attention turns to the quality of life: the families to which individuals belonged, their health, the economic environment in which they lived and the catastrophes that occasionally overcame them (they too have their quantitative features). It is to the family that our attention now turns. The family is society’s most basic social institution, arguably its most important. This chapter is about the family and how it has changed as its economic role has evolved.1

One of the many ways our well-being has improved is that the range of options available is now greater. For instance, we have a much greater selection in consumption than earlier generations. The shelves of the typical supermarket have coffee that originates in Africa or South America, but it is roasted in Verona or Seattle and a hundred places in between. For travel we can go by bus, car, train, air and ship – each at different prices. Even for individual goods or services a range of price options is also available to us that were not earlier in history. The range of options is greater for many other choices. One of the most fundamental is the choice we must make concerning our living arrangements. Do we choose to live alone or as part of a family? Or, where choice is limited as in the case of children who are born into a social condition of class, race, sex, and indeed time, what form do these social arrangements take?

The greater the number and variety of people we meet, the broader is our range of human interaction. This diversity is valued for its own sake and for the options it affords. Undoubtedly some of these contacts will result in a negative experience – we’ve all met unpleasant people, and they’ve met us. Others may be interactions that neither we nor the other individual choose to pursue. There are also those contacts where neither party to the exchange expects anything more than a civil and fleeting interaction. The majority of people fall into this category: the salesperson, the policeman directing traffic, the person that we stand next to in the bus queue and so on. There are yet others with whom we have a more substantial relationship which is developed with greater or lesser intensity: friends, teammates, colleagues, college classmates, fellow supporters of the Chicago Cubs or Newcastle United, and others. But of all the groups with which we are associated, it is our family that occupies a special place.

No simple historical definition can be supplied that encompasses the functional, legal, and emotional dimensions that constitute a family. The family has existed in a huge variety of forms from the multi-generation extended family still found in many less-developed countries to the small nuclear family common in most OECD countries. Usually marriage is the first step in family formation, but it is neither a necessary nor a sufficient step. Today, marriage involves a civil procedure, and in many cases involves a religious ceremony as well. But civil unions are a relatively recent innovation given the long history of the institution of marriage. Civil ceremonies in England date from a specific change in law in 1837.2 They arose in continental Europe and North America about the same time. This did not mean that it necessarily supplanted the religious ceremony – it was part of them in some cases. The coming of civil unions was a response to populations that were becoming more heterogeneous with the increased migrations of the industrial era.

Historically, the marriage itself took many forms, although in essence it is a promise by two individuals to form a pair-bond. The marriage might have been a formal contract (oaths, witnesses and seals) if dynastic rights or substantial property were involved. Usually, the solemnization of marriage took place in a church, but it was not until after a ruling by the Council of Trent (1545–1563) that the rite of marriage entered the Roman Catholic Church as a sacrament. Not until the mid-18th century did it become a rite of the Church of England (Anglican). Even then, its legal and religious features have varied throughout history. Thus, until the past few hundred years, a traditional marriage only required the promise of mutual permanent affection.3 Various jurisdictions had different rules on whether the promise had to be witnessed or not. In some the act of living as a couple implied mutual agreement and thus was legal – and after some time the partner often acquired or shared in the joint property – in the form of the common-law union. Society too had a stake in marriage to ensure the welfare of subsequent children and to guarantee the orderly transfer of property that might be required as the family progressed through the life-cycle. In recent years the legal definition of a family has expanded in order to protect earlier forms, such as common-law cohabitation. The family has evolved to include same-sex unions and various other domestic arrangements. However, only a few countries and states recognize the legality of same-sex marriage – although associated “rights” such as legal dependency for tax purposes are recognized more widely.

As we have already seen (Chapter Four), the typical family is a co-operating economic unit whose function is to make decisions about how the income of the group is to be earned and distributed, both in the present and in the future.4 The economic self-definition of family as a redistributive institution for its members varies by family type. Redistribution raises a compelling distinction: who are family members and who are not? There is a technical definition for census purposes: more than two people who live together and who are related by birth, marriage, or adoption. The household in the census is all those who live in the same dwelling excluding renters. In practice, the family borders are fuzzy and may even change as the need alters. Even in a small, narrowly-defined family, we are more likely to respond with an income transfer to distant family members in an emergency than in unexceptional circumstances. The family also changes as its members age. Parents, once fully responsible for their children’s well-being, provide them less and less as they become young adults and earn some income of their own (although they still may be an investment for pension-like purposes as noted in Chapter Four). The obligations of children have also changed over time. As late as the 19th and early-20th centuries, for instance, it was common practice for working, adult children remaining at home to surrender their weekly pay packet to their parents, usually the mother, who would rebate an allowance. This custom is a rarity today although explicit payments for rent and food may result in a money transaction.

The family, as we all know, is a complex unit where social, economic and personal relationships exist in complicated harmony, and occasionally disharmony. It all starts with two individuals who court one another.

7.2 Courtship and Marriage

Young people in pre-modern times, especially if they lived in a village or rural area as most did, would never meet many others of their age group. Of course, they could extend the number of contacts by embarking on an adventure – easier for men than women – such as joining (or being conscripted into) the army, going to sea, emigrating to another country or running away to town. But, most people lived a settled existence prior to the availability of cheap transport and the advent of industrialization. Historically, with life centered in rural and smaller communities, and with less geographic and social mobility, people necessarily had fewer contacts with others. So the dilemma for a young person was: how to choose or find a partner from a limited set of people. Not that the choice was always that of the young people. In many cultures the choice was that of the parents, and even grandparents. Freedom of choice of a marriage partner was a rarity, although limited evidence suggests that parents began to take into account their children’s preferences once the income-earning potential of women became evident.5 Even then, most marriages were the subject of social engineering by the parents or near kin. However, whether it was their choice or their parents, the same paucity of marital options applied. Today, where notions of romantic love are pervasive and the number of people we meet is large, it is difficult to appreciate fully how the choice of a marriage partner was limited both numerically and socially. For instance, in 18th and early-19th century England, a sample of several major rural county parish records reveals that most marriages were of individuals from within the parish. England was predominantly rural in this era. What is surprising, at least at first glance, is the fact that the proportion of marriages with both partners from the same parish actually increased with time, at least until 1837. One of the main reasons for this unexpected result was that the parishes themselves were of increasing density; more people, more choice.6 As society urbanized, the fact that individuals were from the same parish, especially in the towns, does not imply that they were born and lived their lives in that parish; it only implies that there was geographic proximity for the few years prior to marriage. Choices broadened as the young migrated to urban places.

A Receipt for Courtship, 1805

A young man handing a note to a young woman. The note (we learn from its text) is a caricature of romantic courtship.

Source: Originally published: London: Laurie and Whittle, 1805. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington.

Most places of acceptable social contact for young people were, until the 20th century, rather formal, often less so in North America than Europe. The young might meet at church services where a sly look over the pew was all that was permitted. Schools in the Victorian period, where they existed and catered to both sexes, might afford a slightly less informal setting, although, as students rose in the social order, their schools tended to become single sex ones. In rural societies of the 18th and early 19th century, occasional dances provided another meeting place. These were generally arranged and supervised by the more sober-minded seniors to ensure that there was no undue familiarity among the young. Where the geography allowed, people might be invited from the neighboring parishes. With a view to pre-inspection of possible marriage partners, these social affairs were places to assess the compatibility of the youngsters themselves and, for the older adults in charge, to sort out the likely prospects. Such soirées were class restricted. Dances were held in the grand houses or the ‘assembly rooms’ of towns and villages, but these were affairs of the gentry. The rural working class and farmers had their own dances which were more boisterous affairs than those in the grand houses – think Thomas Hardy. Occasionally they got out of hand and caused anxiety among the supervising seniors; the church denounced them from time to time but did not often stop them. These survive into modern times with the ‘barn dance.’7

The workplace was also a place to meet others of the opposite sex, but it also was a place of possible sexual misadventure. In the pre-modern and early modern periods in Western Europe and North America, most female employment was physically located in the household or on the farm. Domestic and farm chores or home-based production, such as contract weaving (the putting-out system), provided the opportunity for close personal control. The presence of parents and siblings guarded against too much unwanted attention or too much intimacy amongst those of marriageable age. As Jane Humphries has observed, young women who worked outside the home as live-in domestic servants simply transferred parental authority to a third party.8 As noted earlier, the vigilance was not thorough and many young women were impregnated by their employers and other males of the employer household. Close parental control still describes the practices in many less-developed countries today. As the economy became more industrialized, more and more women, both unmarried and married, found employment outside of the home. The young necessarily enlarged the contact group but such contact was still in the presence of older women. Industrial and commercial employers tended to separate the male and female workers through distinctly different female and male work tasks. This also had, from the employer’s point of view, the benefit of discouraging undue familiarity between young men and women because of the supposed disruptions it might cause. Indeed, they may have been required to do so in order to encourage the supply of female labor often controlled by the fathers and husbands.

In the late 19th century, female participation in the workforce increased, and the physical workplace became less distinct by gender. This was associated with the rise of light manufacturing and the service industry in particular. But the pace of urbanization recruited more women to the workforce from urban areas. Social interaction increased, and parental control lessened. In early 20th century France, three quarters of the marriages resulted from young people meeting each other i) at work, ii) in the neighborhood, or iii) by private introduction. However, the greatest first meeting place of marriage partners was iv) at a public dance. These four meeting places and activities, according to a French survey of the 1980s, are only half as important now as they were in the 1920s – although a public dance still rates highly. Neighborhood meetings, once important, are now not a significant contributor to the finding of a marriage partner.9 There are now many more ‘open’ social occasions: college classes, football games, parties, rock-concerts, cruising and others. We suspect that these changes are broadly the same for most Western European, North American, Australian and New Zealand societies notwithstanding the small cultural differences in the courtship ritual. Yet:

cupid’s arrows do not strike the social chess-board at random, but form a diagonal line, perfectly visible in the cross-tabulation of social origins of spouses. How can the multitude of individual love choices converge to give such a result?

Bozon and Heran (1989).

This raises the question: is the choice of a partner in the marriage market strategic? The marriage market is a phrase, recently coined, to analyze the act of finding a partner. Be warned, there is no romance here. It is one of those ‘as if’ approaches to marriage. Individuals are imagined to choose partners that maximize their joint income streams. The relationship is strategic on both sides of the bargain.10 It makes little sense for a lower income earner, especially male, to search for a possible partner among the higher income earners as the female would find them a financially unattractive proposition – see Chapter Four on Strategic Choice. Of course, there would be exceptions.

In a male hierarchical system, women often had little choice of partner – although usually a minimum amount of affection between the principals was a prerequisite to any imposed union. The woman’s family would offer a dowry, a payment to the groom’s family which was often passed on to the couple, at least in part. The function of the dowry (the size of which was often determined in the market) was a persuasion that the bride would not be a financial encumbrance on the groom or his family.11 As such the dowry might consist of property or savings. These may be documented in a formal (legal) agreement as we find in the case of the well-to-do of the pre-modern period. A dowry also might be sufficiently large that it permitted the woman to rise in the class structure. It also worked the other way, as occasionally an implicit dowry was all important since it included a dynastic claim transferred to the new husband – think of this as reducing the necessary cash payment. Medieval history is littered with lesser (but wealthy) nobility marrying women with claims to superior political or social inheritances. But for most folk, the dowry was small and simply confirmed by an oral contract specifying that the bride would be provided with certain goods by her family: cattle, clothes, articles of furniture, bedding and the like. The seeking out of dowries and the level of what was to be expected suggests that the parties were of roughly the same income level. Farm laborers tended to marry the daughters of farm laborers; farmers’ daughters tended to marry farmers.

Dowries, historically, tended to be more common in highly stratified societies. In contrast to a dowry, a bride price is the payment made to the bride’s family for her income claims and reproductive potential. These payments by the groom’s family were (are) particularly common in pre-industrial societies with less well-established social structures.

The bride price was replaced by the dowry as traditional societies became more commercial and industrial. Dowries are found today in South and Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. As Siwan Anderson has pointed out, enforcing the payment of dowries, often paid in installments (some of which come after the marriage), constitute a particular threat to women’s safety in areas such as India where dowry-related murder is all too common.12 Dowries are at odds with freedom of choice and have largely died out as an institution in western societies. An exception is that dowries and bride prices still may be found in some recent immigrant communities.

The lessening of parental or patriarchal control of marriage partners was, as noted earlier, a result of greater contact due to urbanization. Today in Western Europe, North America, Australia and elsewhere, the arranged marriage has given way to greater freedom of choice, to romantic marriage. Pre-selection contact was (is) still stratified, however, with urban location, education, and work force characteristics being the most prevalent and, within these striations, dances continue to attract. All of these are related to income levels. The fact that people of similar social and economic backgrounds and income levels tend to marry each other is not a surprise. The freedom of choice has produced one more result that is very modern – small in number today, but which will increase in the future. Peoples are now marrying across racial and religious divides. Social barriers of race and religion in marriage are being broken down in European and North American society just as earlier legal prohibitions, in some cases, were removed. To be sure, this is a small crack in racial and religious exclusivity. The upswing in the inter-marriage rate was post-World War II. Those at the lower end of the educational scale are least likely to marry outside their ethnicity, while those with higher levels of education are more likely to do so.13

The growth of commercial and industrial economies has tended to promote freedom of choice in recent years, and populations are adjusting to it. China is one country going through a romantic revolution. Half a century ago, according to a study of a rural community in Northern China, only about 4 % of all marriages fell into the freedom of choice category. The majority were either arranged by families or match-makers. Now, as the Chinese rural economies are becoming more commercialized, about one third of all marriages are between individuals who select their own partner.14 It is pleasant to speculate that the forces of economic globalization and the spread of love-based marriage are causally linked.

7.3 Household and Family Size

In pre-modern times the typical family was large with several generations living as part of the same household. Sometimes they included nearly-related kin. With the beginning of the industrial and demographic transitions, the geographic mobility of individuals meant that the family, while still large by today’s standard, was more spread out. But, at about the same time, child mortality declined so the dependency rate of the young rose and households remained large. In the 20th century, the nuclear family (parents and a small number of children) evolved out of the fall in fertility and the increase in women’s employment outside the home (other things equal). Today the so-called nuclear family is slowly disappearing in the OECD countries and is being replaced by DINKs (double incomes, no kids) and the various other forms of post-second demographic transition families. Nuclear and extended families, however, do still exist. Yet the cross-sectional evidence shows that they are rapidly disappearing. We can square these observations by noting that the modern, and now traditional, nuclear family in which an individual may find themselves is a form that varies with age over an individual’s life-cycle. Many families in the developed world today may be part of several types of family in the course of their lifetimes: a non-nuclear family at some stage such as a childless cohabitation, enter a nuclear (perhaps an extended) family with wide contacts when they have children, then withdraw to another type of family such as a retired couple or into a single person household. The fact that families now have fewer children means that there will also be fewer siblings, aunts, uncles and cousins. What will we do in a world with so few aunties?

US Census definitions

Family Size: Number of individuals in a family. A family is a group of two or more people who live together and who are related by birth, marriage, or adoption.

Household Size: The total number of people living in a housing unit (excludes those in institutional settings – such as group homes, shared units and others). Note that a household can be a few as one person. It takes at least two people to be a family.

Family Household (Family): A family includes a householder and one or more people living in the same household who are related to the householder by birth, marriage, or adoption. All people in a household who are related to the householder are regarded as members of his or her family. A family household may contain people not related to the householder, but those people are not included as part of the householder’s family in census tabulations. Thus, the number of family households is equal to the number of families, but family households may include more members than do families. A household can contain only one family for purposes of the modern census. Not all households contain families since a household may comprise a group of unrelated people or one person living alone.

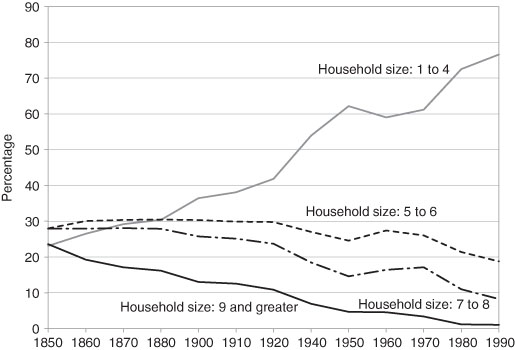

Figure 7.1 Household Size by Decade in the United States from 1850 to 1990.

Source: calculated from data in Haines (2006) US Historical Statistics, Ae85–96.

In 1790, at the time of the first US Census, the majority of households had seven or more people in them. An astonishing 29 % of households had nine or more people. Although there is no quantitative evidence for the following 60 years, the pattern of household size appears to have changed only little – see Figure 7.1. But, beginning in 1850, there was a remarkable shift from large to small household size that was continuous on a decade-by-decade basis. By 1990 most people lived in small households (four persons or fewer), and only about one % lived in households of nine or greater. Today, the mean household size is 2.6 persons and the completed family size is 3.2 persons – some children or one of the parents may have left the household making household size smaller. An historical difficulty is that family size (parents and children) and household size is not the same thing. The household may include other relations living with the family and exclude children not living at home. Nonetheless, future household size in the US is predicted to stabilize as we move through the 21st century according to researchers Leiwin Jiang and Brian O’Neill, even with widely varying assumptions about the marriage rate, divorce rate, fertility and life expectancy. The extreme range of their projections to the year 2100 is 2.0 to 3.1 persons per household; their best estimate is about the level we have today, even though they project change in household composition such as more single-persons, more co-habitations and a slight increase in marital fertility.15

At the end on the 20th century household size in most developed countries was remarkably similar. Even in the least developed world, the average household size was less than that of the Americans just after the Revolution.16 As the sociologist David Kertzer notes, there is much debate about the role household size has played in history. Some claim the small nuclear family was an outcome of the industrial transition from agriculture to urban industries. The counter-claim has been that nuclear or small extended households existed before the transition got underway and, indeed, was partly responsible for the faster economic growth of the leading countries. Was it effect or cause?17 The answer is that it was both; there was feedback. The European marriage pattern with its late age of marriage restricted the marital fertility of households by reducing the ‘at risk’ period. This created savings (see Chapter Nine). It also meant that the family was more mobile and could relocate to urban centers and establish themselves at a lower cost than larger families. Also, the evidence in Figure 7.1 illustrates that there was a greater variation in US household sizes in 1850 than today. Of the four size groups shown, all were roughly equal in importance in the early US, where the European marriage pattern was also prevalent. The rewards for having fewer children would tend to alter the behavior of those with larger families. After decades of convergence to the small family size, there is now less household variation. Nearly eight out of ten households accommodates four or fewer people.

Within the household, the family is involved in three economic relationships. The first is the set of principles governing co-operation among the members. Who washes the dishes? Second is the issue of who owns the physical edifice where the household lives. Of course, home ownership was a relatively rare event until modern times. (American, Canadian and Australian home ownership was always greater than that in Europe and Asia.) So we must also consider who has the rights of rental, the claim on the tied-cottage or other forms of possible tenure. Third are the obligations of those in the household to the individual(s) who have the established rights of tenure or ownership. As Robert Ellickson argues in his exceptional history of household structure and law, these relationships are mostly informal (or implicit) in order to keep the transaction costs down.18 However, the terms of co-operation among household members are not always determined in an equitable manner. Patriarchal households are fairly common even today in many parts of the least developed world and are not unknown elsewhere. There, the free negotiation of terms of co-operation among members of the household is not an option. Until the individual (adult) household member has freedom of exit, the institution of the household is less flexible. The emergence of a more liberal household arrangement was one of the key foundations of European and North American economic growth. It permitted the supply of labor to expand through its mobility.

7.4 Child Labor

It has only been since the middle of the 19th century that a substantial number of families could afford to give their children a “privileged” upbringing, to forego the additional family income that the children’s labor would produce. In most agrarian societies, children worked (and still work) alongside their parents from the time they were old enough to retrieve eggs from the hen-house. Outside farming, an apprenticeship has been part of an artisan education since the Middle Ages.19 With industrialization, many children went to work inside the factories with their parents. Even more went to work apart from their parents, a situation that gave rise to much criticism of the basic concept of child labor. As education came to play a greater role in determining one’s position in the adult labor force, the children of the bourgeoisie remained in school rather than joining the labor force.20 However, the practice of child labor is still very much with us, especially in the less developed parts of the world.21

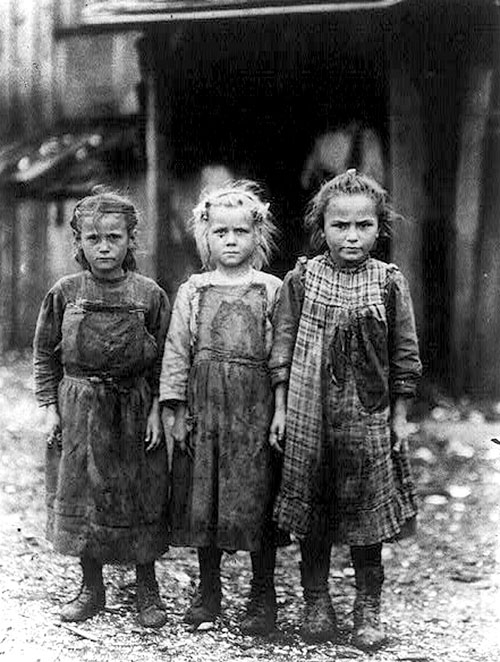

Oyster Shuckers in a Canning Factory in South Carolina, 1909

This photograph was part of the evidence collected in 1909 by the National Child Labor Committee set up by the US government to investigate the extent of child labor and to make recommendations about uniform laws regulating child labor across the states. It shows, with their reported ages, Josie (5), Bertha (6) and Sophia (10) who worked as full-time oyster shuckers in the Maggioni Canning Company of Port Royal, South Carolina.

Source: Photograph from the records of the US National Child Labor Committee, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington.

It is logical to ask the question, why do children work? It should not be surprising that there is no good answer to the question. There are many motivations, including a desire to work on the part of the children themselves. In addition to the fact that children had traditionally worked, there seems little question that the ample supply of children available at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution coupled with a family’s need for income were among the principal reasons for the existence of child labor. It was also the case that there was a demand for the labor of children, especially since their wages were low and they were unlikely to form labor unions. Further, as several scholars have noted, their small stature and nimble fingers were ideally suited to the type of work situations created by the Industrial Revolution in textile mills and mines. As economic development contributed to increasing family incomes and technological change moved away from the small scale, simple machinery that had given children a comparative advantage, child labor disappeared. By World War II, it was largely a thing of the past in developed nations, but it remains in the less developed world.

Historians have largely focused on the large number of children who entered the often-bleak factories of the late 18th – early 19th centuries. They have decried the deplorable conditions of those factories for children, but the adults breathed the polluted air as well – and the whole family had to breathe it at home. Other historians have argued that the decision to work was economically rational, given the alternatives.22 Clearly, the decision to work is one that was made in the context of the society of which the children were a part. Today, there are laws in many countries that specify the age to which a child must stay in school, but that age is almost always younger than what the law considers to be the age of consent. A child’s decision to work may be viewed as unacceptable if the child is 15 and acceptable if the child is 17. For many, especially those children who lived (or live) on farms, there was no decision to make; work was (and is) a natural part of life. And, if we go back into the dim mists of history, everyone worked to survive. The debate over whether children should work first required a great deal of economic development.

Children should be productive members of the family, but in developed countries today those chores are largely unpaid (weekly allowances notwithstanding). Parents had worked when they were children, and they expected their children to work. As suggested above, some boys worked apart from their families as apprentices; girls would leave home around 12 to become domestic servants. By the 16th century, a significant number of young people were employed as servants in husbandry.23 Living away from home, the girls performed chores such as milking, weeding, and cooking, while the boys looked after the work animals, ploughed, and drove the carts. There is ample evidence that, when the Industrial Revolution arrived, children were not entering the labor force for the first time; their conditions of work changed.24

Those conditions were often troubling, even before widespread employment in factories. The most cited example is that of the “climbing boys” of British chimney sweeps. It is alleged that boys as young as four would climb narrow chimneys to scrape soot. Britain’s 1788 Act for the Better Regulation of Chimney Sweepers and their Apprentices, was to protect such children. It required that apprentices be at least eight years old, but the Act was generally ignored because there was no means to enforce it.25 With the first rural textile mills (c.1769), and the expansion of coal mines, the perception of child labor changed for the worst. “The dark satanic mills” of William Blake’s poem became, in E.P. Thompson’s prose, “places of sexual license, foul language, cruelty, violent accidents, and alien manners.”26 In brief, no place for children, but many of them were assigned to such places by orphanages and workhouses. They received food, clothing, shelter, and (most likely) no wages. Estimates of the number of children employed in rural mills average around a third of that labor force, but the fraction was much higher in certain mills. Children also worked in the mills and mines of Belgium, France, Germany and the US as they industrialized. When the steam engine freed mills from having to locate adjacent to water (so a waterwheel could provide power), the mills became less rural, more urban. The demand for coal increased. Children from poor, working-class families replaced orphaned apprentices. This seems to have intensified the debate over the effect on children, a debate that remains as vigorous today as it was then.

Among those who argued that industrialists were exploiting children and subjecting them to unhealthy working conditions were Friedrich Engels, Karl Marx, and Beatrice and Sidney Webb. Their position was that children as young as five worked indoors, sunrise to sundown, every day but Sunday, in poorly lit, overcrowded factories and mines. They called upon Parliament to pass laws to help correct the situation. On the other side of the debate, Andrew Ure and John Clapham argued that, to make a contribution to their family’s income, children were performing light work under conditions little different than those under which they worked before industrialization. Both sides presented an impressive array of information to bolster their position. After a good deal of Parliamentary debate, a Royal Commission was created to investigate the situation. As a result, Parliament passed several laws setting the minimum age of employment at nine and the maximum daily hours at 12 (c.1819) before lowering them to 10 (c.1847). Given the experience with the 1788 law, a cadre of factory inspectors was created to enforce the laws.

The situation in the US was very similar to Britain. Everyone worked on a family farm. Fieldwork was generally the responsibility of men, while women and children performed tasks closer to the house and garden. Children appear to have had a relatively low productivity on northern US farms.27 Indeed, it has been argued that the first areas to industrialize were those where the productivity of women and children was low relative to adult males.28 Northeastern women, who were described as “redundant” with respect to agriculture, became actively involved in the putting-out system. By 1832, with the shift away from artisan shops toward small factories, the percentage of young Northeastern women (ages 10 to 29) involved in wage work was 40 % of the industrial work force in the Northeast. Typically, they pooled their incomes with other family members.

The first American textile mill, that of Almy and Brown, opened in 1790 in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. The first large-scale New England industrial town was Lowell, Massachusetts, owned by the Lowells of Boston. In the search for a labor force, Samuel Slater, partner to Almy and Brown, is often credited with launching the family system of labor in which children tended machines for their fathers. The Lowells generally hired single New England farm girls for whom they constructed clean, well-supervised dormitories. The labor of the “Lowell girls” was compensated at a relatively low wage, but the wages the Lowells paid were higher than the girls could have earned by staying on the farm. Although the share of children in the industrial labor force began to decline as early as 1840, it remained an important part of the textile industry into the early 20th century.

The first statistics on child labor in the US are from 1880. For children 10 – 19, the labor force participation rate was higher for rural children than urban ones, higher for boys than for girls, higher for foreign-born children than for native born, and higher for blacks than for whites.29 Statistics from the Cost of Living Survey of 1889–90 indicate that for urban households, the income produced by the children was important to the family’s income. The income of the principal breadwinner peaked when he was in his 30s, but his family’s income didn’t peak until he was in his 50s.30

As was true in Britain, the fact that children still held industrial jobs at the end of the 19th century was viewed with alarm. As the high-school movement took hold, it became clear that children who quit school to work were reducing their lifetime income potential, a story that is told today about high-school dropouts.31 Parents were seen as sacrificing their children’s future, but the normal trade-off was an increase in the family’s income. Employers were accused of assigning children to dangerous jobs, then bullying them if they showed any hesitancy. As in Britain, the US response to the situation was labor legislation. The first state law was passed in Massachusetts in 1837; in order to be considered for employment in a manufacturing firm, children under the age of 15 had to have attended school for at least three months in the previous 12 months. By 1900, 44 states (and territories) had passed similar laws. On the other hand, federal legislation was ruled largely unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. The most celebrated attempt, the Keating-Owen Act of 1916, was set aside two years later in the Hammer v. Dagenhart decision. It was not until the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 that a federal statute was found constitutional.32 By then, child labor had almost disappeared in the US and other developed countries, but not so in the developing world.

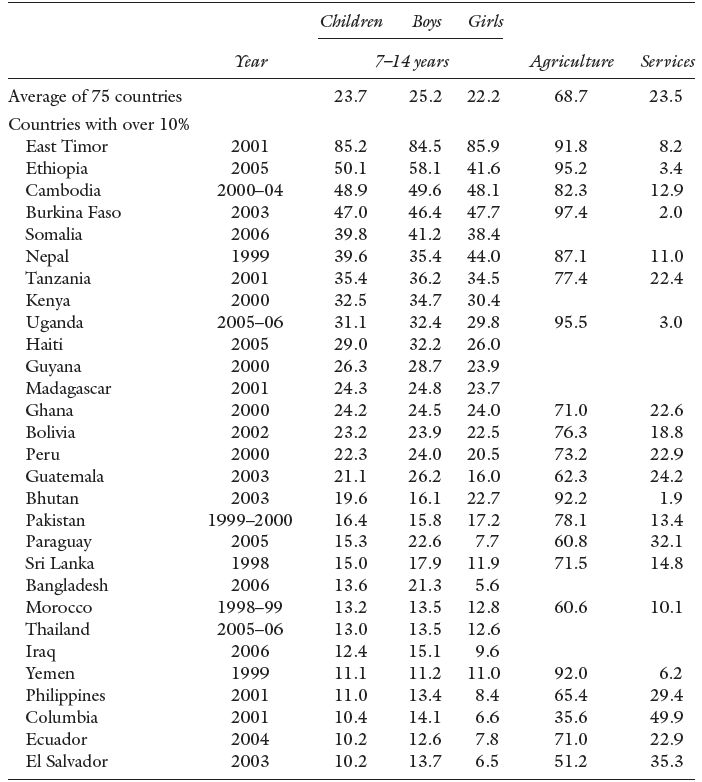

The US Department of Labor publishes an annual study on child labor to assure that the country is not unwittingly abetting the problem through international trade. The most recent is entitled The Department of Labor’s 2008 Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor.33 This is a country-by-country report, and in Table 7.1 the top line reports the average percentage of all countries reporting the percentages of boys and girls aged 7–14 that are working. There are 122 countries cited in the monitoring with details about 75 of them. From these 75 countries averages are computed; only the countries with more than 10 % of their children working are shown in the table presented here. It should be noted that the reports are for different years. The percentages of children working in agriculture and the service sector are also reported in Table 7.1. As can be seen, roughly speaking, a quarter of the children in these countries work, a slightly higher percentage of boys than girls. Over two-thirds of them worked in agriculture, and just under a quarter of them worked in the service sector.34 A country that reported these average percentages is Ghana, and we will take a closer look at what the report had to say about child labor in Ghana.

Table 7.1 Children in the Labor Force, Selected High Percentage Countries, Various Years (working children as a percentage of children in the age range).

Source: US Department of Labor (2009) 2008 Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor.

The countries reported in Table 7.1 were chosen to reflect the diversity of experiences found in the report among all countries with more than 10 % of their children working. Far and away, East Timor is the country with the largest percentage of children reported working, and the vast majority of them were in agriculture. Only eight of the 75 reported more than half of their children were in the labor force, and most reported little difference between boys and girls. Other than East Timor, the other seven countries are in Africa. Even in the middle of the distribution, most of the countries are in Africa. Countries from Central and South America, the Middle East, and Asia all reported much lower percentages.

Of the 40 countries reporting a sectoral division of child labor, all but six report that a majority of the children worked in agriculture. The lowest (18.5) was reported in the Dominican Republic where under 6 % of the children work and the majority are reported in the service sector. Indeed, the only two countries reporting a greater share of children in the service sector than in agriculture are Chile and Venezuela, where an even smaller percentage of children are in the labor force. The purpose of the Department of Labor report, however, is not to provide such statistics, but to look inside them and see what the children are actually doing. For that, we turn to Ghana.

The agricultural work that occupies 71 % of the children involves the production, harvesting, and loading of a variety of food crops and livestock. Under Ghanaian law, the minimum age for employment is 15 for heavy and 13 for light work (that which neither interferes with education nor is harmful to health). The Department of Labor report singled out for special consideration the estimated 1.6 million Ghanaian children involved in the cocoa sector, some as young as five.35 This work was reported to involve several hazardous tasks, including carrying heavy loads, spraying pesticides, using machetes to clear undergrowth, and burning vegetation. Ghana’s service sector employs 22.6 % of the children in activities such as street vending and fare collecting. As early as age six, girls in urban areas carry heavy loads on their heads. These girls are often street children and vulnerable to being exploited in prostitution. In the major urban centers, the capital city of Accra and the coastal tourist cites of Elmina and Cape Coast, children are engaged in commercial sexual exploitation and, at least in the coastal cities, the sale of drugs. Ghana’s Ministry of Women’s and Children’s Affairs (MOWAC) estimates that thousands of children are involved in the sex industry in Ghana.36 Much of this involves the “trafficking” of children and forced labor, both of which are illegal. Ghanaian children are trafficked both internally and to and from neighboring countries in West Africa.

Ghana’s manufacturing sector employs 5.8 % of the child labor force. Both boys and girls are found in quarrying and small-scale mining activities such as the diamond and small-scale (illegal) gold mining. Both are involved in the fishing industry on Lake Volta; many of them have been transported there.37 The work is hazardous for the boys who perform tasks such as deep diving and the casting and drawing of nets. Girls are domestic servants and cooks in the lake’s fishing villages; they are also involved in the preparation and sale of fish for market. It is traditional in Ghana, as elsewhere, to send children to Koranic teachers, and this may involve a vocational or apprenticeship component. In addition to the education, many of the students are forced by their teachers to obtain money and food, and this usually involves begging.

The Department of Labor report goes on to discuss the efforts Ghana’s government is making to reduce abuses. And it should be emphasized, the reason Ghana is discussed here is that, statistically, the numbers it reported are almost exactly equal to the averages for all 75 countries that reported data.

The detail contained in the country-by-country reports of the Department of Labor study hearkens back to the anecdotal evidence one finds in relation to western European and North American children at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. Absent words like “trafficking,” children today work in areas where children have worked for centuries. In many parts of the globe, they continue to contribute to family incomes still too small to enable them to invest in their human capital that would have the potential to increase their family’s income in the future. And, in specific parts of the world, investments in human capital are still being denied to women. What Ghana’s experience suggests is that child labor is still very much a part of family decision-making. Indeed, note was taken of the fact that some parents still engage in what has been a traditional practice of sending their children to live with more affluent relatives (or family friends). Family connections were, and remain, an important part of the institutional setting in which child labor occurs.38

7.5 Family Connections: Networks

Families exist within networks of similar families. Sometimes these families are related genetically as an extended family group (cousins, second cousins, great-aunts and so on) and sometimes they are part of a network linked together by other shared characteristics such as social origins and religious affiliations. We have already seen this at work in the 19th and early 20th centuries in the German and Italian immigrants to the United States. In the less-developed world, they are often part of the mechanism that supplies child labor as we saw in the previous section. Irish policemen came to dominate certain metropolitan police departments in the US in the late 19th century. In Portugal, Basque fishermen banded together, shared information, controlled their output (by capturing the organization of the markets) and through that activity, manipulated prices.39 Family networks provide benefits for their members, but they often do so by retaining an exclusivity of information which necessarily lessens the opportunities of outsiders (a social cost). At the limit, family networks may act in a collusive fashion or function as a discriminatory mechanism. However, the history is not so clear cut. This section deals with networks in two cases: self-help and business management.

Family networks act as social support for their members. In this sense they are like an insurance scheme (or, as noted in Chapter Four, a pension-like arrangement for close family members). The implicit premium is the reciprocal nature of the obligation to help. In this fashion, “families” may be extended well beyond the immediate family to include close friends who fulfill the same social support on a wider basis. A 1980s study of a low-income population in rural Georgia revealed that women had support networks that were approximately double the number of family relatives. The networks were not large, however, ranging from 6.06 for black Americans to 7.82 for white Americans (means). Professional help was generally absent from the networks of these poor mothers.40 We do not know whether the experience of these rural folk can be generalized to look backward in history, but it seems likely that we can. Although these rural-poor networks are small, the networks often are quite large. Members of certain religious communities tithe. Historically, they give a portion of their personal incomes (a tenth for example) to provide assistance for beneficial social projects. The insurance premium is now explicit. There is a long history of such tithing in communities such as the Ishmaeli Muslims and the Society of Friends (Quakers). Apart from the social care of their members at a local level, they also engage in support well outside the networks – educational support is an example. Another historical instance of tithing comes from the European monasteries and nunneries during the Middle Ages. They received tithes from the more prosperous with a promise that they never would be left destitute. While acting as a social support network with unwritten (but implicit) terms of reference, yet networks often provided a well-defined benefit for their members at an explicit price.

Such is the case of the mutual self-help societies which arose in Britain in the 18th century and subsequently spread to North America. These organizations were essentially working-class and fraternal. That they had, to our ears, exotic names (Oddfellows, Knights of Pythias and the like) should not lead us to underestimate the seriousness of their purpose. They provided a service which neither families nor the state could provide, an insurance against the risk of unemployment due to illness. Sickness insurance benefits were received by those who were accepted into a fraternal order, enrolled in an insurance scheme, and paid a weekly fee. It also covered accidents and longer-term disability. David Beito and Herb and George Emery have carried out a series of economic studies on these fraternal orders in North America whose provision of health insurance for members was a principal reason for joining. What they have shown is that the fraternal orders were remarkably efficient in providing coverage for their members. Despite being organized at the local level into so-called lodges, they operated on sound accounting principles and got their prices right, neither too high nor too low. They avoided the insurer’s free-rider problem (false claims) by two of their provisions. One was the waiting periods before receipt of benefits. Second, a high degree of moral suasion was applied. The elders, the executive of the lodge, would come and visit to ensure the illness benefits were warranted and, because the lodges were essentially local, they brought community social pressure to bear to prevent “malingerers” from applying for benefits. So successful were these fraternal networks that together they covered a large proportion of the white, working class males – a majority in some areas. In parallel, there was a similar set of black-based fraternal orders. It was as if the societies limited their networks to well-perceived risks, within which the moral responsibility of members could be guaranteed. Ultimately the fraternal societies died out in the second quarter of the 20th century. Their demise is a subject of much discussion among economic historians. It is most likely that they succumbed to the employer-based schemes which provided superior benefits and which emerged in order to attract labor to particular employers. Also, and particularly in Britain, the advent of national insurance and universal health arrangements crowded them out.41 Yet, the importance of the self-help fraternal orders should not be underestimated: for more than a century they provided sickness insurance to a substantial part of the working-class population that was ignored by the market.

Networks were also important in the world of finance. In the Middle Ages, Venetian bankers and Jewish financiers operated their arbitrage over long distances because i) they had developed specific instruments to effect a transfer of savings; and ii) they had a network comprised of individuals who would honor the instruments – bills of exchange, for instance. The individuals regarded their networks as completely trustworthy. The personal relations of the network members reduced the risk of the transactions, thereby making them possible. The networks also allowed individuals to work co-operatively. Ann M. Carlos, Karen Maguire and Larry Neal point to the case of the London Jewish community acting in concert to buy the stock of the Bank of England as it declined in value during the South Sea Bubble in 1720. They voluntarily accepted losses on the bank stock. It is conjectured that this was to prove their reliability and gain a permanent place in the growing London capital market. It is also likely that this action also gained them more social acceptability in the long run.42 Only a tight network where the participants fully understood the reasoning behind the action and the shared long-run goals could have achieved this outcome.

A key rationale for the existence of networks is that they allay risk. Risk in finance and investment has many dimensions, the principal of which is the flow of knowledge. But it did not always spread with equal ease over distance because of communication inefficiencies and over the technical distance between industries. Networks help leap the barriers to capital formation. During the period between the US Civil War and World War I, several things happened simultaneously: the investment rate rose, industrial restructuring of the economy was rapid, mortality fell substantially, fertility was on a downward path and net immigration flows increased. One key economic feature of this period was the rapid evolution of capital markets. New demands for investment led to the creation of new financial instruments and new markets for their sale. This period has become known as the “age of finance capitalism.” In the United States the movement of savings across these barriers to capital formation owes a great deal to the entrepreneurs of the day. Their names are familiar even today.43 In all these countries the managers of capital were part of networks, albeit very loose ones. They were knit together by social class, education, religious background and, occasionally, by family ties through intermarriage. That is, they went to same schools (or type of school), worshipped in the same churches, were members of the same clubs, married off their children to each other and went to the same places for holidays (Cape Cod or the Isle of Wight).44 They shared the same values, passed on information to one another and co-operated, sometimes competed, in the same markets. Why would individuals who competed with each other be part of the same network? It is the same as having a hateful cousin. You may not like them but, because you share so many social characteristics, you can read them like a book. That is, and more so for co-operators, information that has not been observed by the market for financial capital is acted upon. The act of moving capital over barriers created rents to scarcity (or super-normal profits). The rents stir others into action and many actors create an institution called the market in the instruments of ownership (bonds, mortgages, insurance and shares, to name a few). The actions of the networks then are beneficial to the emergence of more efficient capital formation, while, at the same time, any attempt by members of the network to act collusively will be to its detriment. It’s a trade-off.

7.6 Marital Dissolution

In the days of the Roman Empire divorce (a legal end of marriage) was relatively common, but only for the members of the patrician class (and there were clan grievances to be reconciled). Muslim society also had lax divorce laws, although the untangling of marriage contracts and various families’ allegiances meant that it was complex, expensive and, consequently, relatively rare. Pre-modern European marriage dissolution practices are not well-documented except in the case of dynastic separations where an annulment could be sought from the bishop or pope – presumably with the appropriate payments to ease its passage. Perhaps the most celebrated divorces were those of Henry VIII whose domestic affairs were one of the reasons behind the split of the Church of England (Anglican) from that of Rome.

Divorced, beheaded, died;

Divorced, beheaded, survived

45

memorializes these divorces, and the fates of Henry’s other wives – useful in order to keep the order of the queens in mind, a British schoolboy trick! Henry’s divorces notwithstanding, neither the Church of Rome nor the Church of England permitted divorce, although they did recognize a legal separation – which naturally ruled out remarriage – except in Henry’s case. In the 18th and early 19th centuries in England, divorce was an option only for the very rich since it required the passage of a specific act of parliament naming the individuals. Civil divorce did not become an option in English law until the mid-1850s, and even then it was limited as to cause and unequally applied in the case of men and women.46 The Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857 and The Divorce Act of 1857 introduced civil procedures for divorce on the grounds of adultery in the suits brought by men. For women the requirement was to find evidence of both adultery and other grievous offenses in their suits – adultery was a necessary but not sufficient condition.

In those countries of Western Europe that retained the established Roman Catholic religion, divorce was only introduced as part of a regime change. France, for instance, introduced liberal divorce measures early in the Revolutionary period; it subsequently revoked these laws and made divorce illegal until another sudden change in 1884.47 Somewhat similar sea changes took place in the divorce laws of the east. Both Japan and China had traditional, but different, marital dissolution practices until recent history. Japan in the pre-modern period had an exceptionally male-oriented divorce law; women had very few rights – if any at all. A Japanese male could simply write a three-line letter to his wife indicating that he divorced her. Interestingly, most marriages so dissolved were early in the union before children were born. Today, under its post-1945 law that roughly resembles divorce law in the west, the mean age of divorce is much later in life and normally takes place after the birth of children.48 Although there is some historical questioning of the arbitrariness of pre-modern Japanese practice, there is little doubt about the one-sided benefits. Chinese law also changed radically only in the 20th century with the coming of the Communist Revolution which introduced compulsory mediation as part of divorce. This may reflect an older Confucian Chinese custom. Since the end of the Maoist Era, the country has adopted more explicit and balanced divorce proceedings, but it has not entirely given up on mediation.49

As they emerged in the late 16th and 17th centuries, the Protestant states of Europe (except England) permitted divorce from their inception as they did not include marriage as a religious sacrament. Scotland, for instance, gave men and women equal access to divorce either on the grounds of adultery or abandonment. The parties could then re-marry. But, the Scottish divorce rates, for the most part, seem well below the rate of Scottish marriage dissolution despite their liberality. The cost of finding the evidence, witnesses, paying lawyers and, one suspects, the social embarrassment was simply too high. Ordinary families that suffered a broken marriage seem to have simply reconstituted themselves in new, but separate, common-law arrangements (probably as bigamists, but with community acquiescence).50

Divorce Rates may be defined in a variety of ways. Below are some of the common variants and where found:

a. the number of persons divorced in a year as a percentage of married people (stock) in the same year (mid-year population). England and Wales.

b. the number of divorces in a year per 1000 adults (mid-year population). USA

c. the number of divorces in a year per 1000 married adults (mid-year population). USA

d. the number of divorces in a year per 1000 total population (mid-year population). OECD

e. the number of divorces in a year per 100 marriages in the same year.

In the second half of the 18th century, roughly coincident with the first phase of the Industrial Revolution in Western Europe, a social change of attitude toward marital dissolution took place. The history of divorce records a fairly sharp increase in divorce proceedings in most non-Roman Catholic jurisdictions in North America and Western Europe. Naturally, there is considerable speculation as to why this occurred and why it was so widespread. Perhaps there were some minor changes in the laws in the late 1700s that seemed very attractive to those at the time, but we do not perceive them as such in the 21st century. But more likely, it was the shifting economic environment of the late 1700s. The period marks the beginning of the shift of the work-place to urban areas, the growth of individual incomes and the growing range of people met – giving rise to new expectations of romantic attachments and new opportunities to commit the act for which divorce was suited to deal. Indeed, adultery may have become a more common occurrence.51 However, this sudden up-take in divorce proceedings did not lead to further increases. For that we had to wait until the mid-20th century.

Social improvers throughout the Victorian and Edwardian eras brought divorce problems to the public gaze: the fate of abandoned females and children, the non-payment of court awards for maintenance (still a continuing problem) and the drive for equitable access to divorce proceedings by both sexes prior to World War I.52 The rapidly growing sympathy (admiration) for women’s suffrage due to female contributions to the war effort was an important fillip to gender equity concerns. In England The Matrimonial Causes Act of 1923 finally evened the playing field in law: equal access and equal causes.53 English men and women born in the first five years of the 20th century had a divorce rate of 4 % (of their marriages), most of which occurred in the 1920s and 1930s. Then the revolution came. In the aftermath of World War II, many marriages broke down. The pressures of wartime and disrupted lives all contributed. The increased marriage rate led to more divorces with a lag of about a decade. But married people demanded more; it was as if they developed a taste for a new good. Easier access to divorce and expansion of the terms were among the reforms demanded along with a lower price (cost). Those born in the years 1945–1949 and who were married had a 27 % likelihood of their marriages ending in divorce (and it is not over yet). Most divorces among this group were not the end of two-parent families, however. Eight out of ten women whose first marriages ended with a divorce remarried, usually within a short period of time. The remarriage rate was even higher for men, over 90 %.54

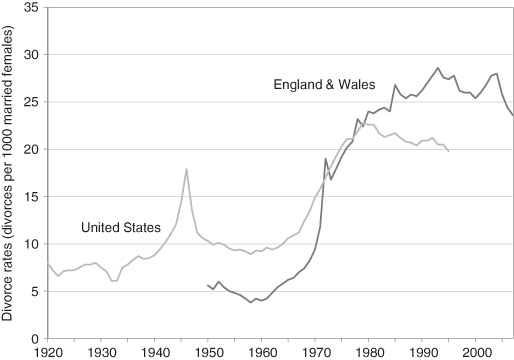

The widespread, but much exaggerated, “sexual revolution” of the 1960s was one of many forces that lay behind the movement for a “no fault” divorce system. No fault divorces were first introduced in Sweden in 1915 and, although they became the model for subsequent reforms, did not pass into the law of other countries for about 50 years. Fault of course implies the finding of its proof. This applied in most European and North American legal jurisdictions. There was a loophole. The parties wishing a divorce could collude to find a solution. The typical grounds for divorce by the post-1945 years were: adultery, desertion, physical and mental cruelty, long imprisonment for a felony, and persistent drunkenness. It was by far easiest to collude on the grounds of “adultery” – all that it required was a good story and an actor willing to accept the (small) likelihood of being found out. The institution of the “law of divorce” became untenable under these practices. Divorces increasingly did not involve children. The cultural shift that is the second demographic transition (Chapter Four) was background to the decline in the total fertility rate. Within marriages, children tended to be born later in the life of the mother. So in more and more marriages, the existence of children and their welfare was not an issue. “No-fault” divorces found a general legal and popular acceptance where one individual could initiate the proceedings and freely declare that the marriage had irretrievably broken down.55 The granting of a divorce generally involved a short period during which the divorced person could not re-marry – a puritan holdover. The divorce patterns of the recent past, since the reforms of the 1960s and 1970s, have been very similar across countries. Divorce rates rose after the reforms of the late 1960s and 1970s for about ten years or so then stabilized and very recently have begun to decline – see those for the United States and England and Wales in Figure 7.2.

How much the divorce law reforms contributed to the divorce boom is a matter of controversy. Some observers claim that the reforms were responsible for a permanent rise of the divorce rate by about one-sixth. Others claim that much of the divorce boom was due to the rush for earlier dissolution of unhappy unions and that moved the divorces forward by about a decade.56 This was a once-and-for-all shift, and, thereafter, the greater reluctance of young people to enter a marriage and the increased non-marital cohabitations meant that the stock of marriages in the years 2000–10 did not face the same high risk for divorce as earlier marriages. However, the probability of divorce from a first marriage tends to be close to 50 %, and the probability of a second divorce is even higher. As observed across the US social spectrum, divorces become more frequent the lower the income of the male partner. There does not appear to be any relation to female income.57 From the point of view of the individuals, the issues of divorce now become: the division of assets of the marriage and the compensation to spouses, if indeed there are mandated payments. From a social perspective we have to ask if and how the divorce puts families at risk to become poor.58

Figure 7.2 Divorce in the United States and England and Wales, 1920–2007.

Sources: UK (current), National Statistics On-Line, Historic Divorce Tables: United States (current), National Vital Statistics, CDC On-Line.

Note: The broad features of Canadian divorce rates followed that of England and Wales. About 40 % of Canadian marriages end in divorce. This includes all marriages whether first, second, third or other. The data also show that the divorce rate is generally higher for each subsequent marriage after the first.

7.7 Married Women’s Property

Modern feminist historians argue that marriage and how it was (is) arranged has much to do with individual male-female power relationships. In a historical context, for instance, marriage usually meant an actual transfer of the female’s property to the male spouse or, at minimum, a transfer of a claim to her property. Prior to the reforms of the 19th century in Western Europe and North America, this meant that married women had few rights to property, although they did have some. For instance, the settlement of a sum of money on a woman in her right was a common practice of the wealthy. These were called dower arrangements and, amongst other reasons, were designed for her provision should she be widowed, which was likely given life expectancies. They were kept separate for the male spouse’s property by a legal trust. Although a woman’s legal rights to own and dispose of property ceased to exist once married, they could return in widowhood. On the other hand, a “never-married” woman had more or less complete authority over her property on the death of her father. This might have been a reason for choosing that state and may explain the high rates of the “never-married” which we find occasionally over time. Changes in the legal property rights of married women were effected over the course of history by two other major developments: the changing legal status of primogeniture and married women’s participation in the workplace.59

Primogeniture is the legal imperative of passing on an entire estate to the eldest son. It is often held that the law of primogeniture was partly responsible for the late age at marriage of European males. The eldest son would have to wait until his father’s demise before being able to set up an independent household. There are several problems with this argument. First, younger sons, those who were not scheduled to inherit, also displayed a late age at marriage. Their economic independence was hardly fashioned by the death of a father. Second, most males in countries under primogeniture did not inherit anything. The heritable right of farm tenure as a renter/tenant might be an exception to this for ordinary folk, but tradition suggests that this right was essentially conveyed long before a parent’s death, and the legal transfer was made later. Third, where we have side-by-side examples of the two legal systems – primogeniture and multi-geniture – as in pre-Revolutionary US and colonial New France, both had very similar ages at marriage for men and women. To be sure, it was slightly lower than that of their European brothers and sisters, but it was not that much lower. Further, one would expect a North American to have a lower age at marriage because of the relative abundance of land and the ease of establishing an independent household. Finally, as noted in Chapter Four, primogeniture was a legal practice that was widely violated by a family’s internal redistribution of the father’s estate.

The law regarding women’s property holdings within the family began to change in the 19th century on both sides of the Atlantic. The pace of change was slow because, it is claimed, the modification of the law was in male hands. The economic pressures, however, were evident to all. Male-held property could be sought in the courts by a creditor seeking relief, but what of the assets that a female held in her own right and what of the assets legally held by the male spouse but brought into the marriage by his wife? The laws were for the most part ambiguous. This was complicated by two other contemporary practices. First, if male-held assets were hidden in the wife’s portion, did this disguise make them free from claims? It did not. Second, what happened to the assets or the debts of the male spouse when he absconded? It appears that in North America the assets of the male spouses usually escaped effective detection when pursued for reasons of debt or marriage breakdown; the geography was too large. To resolve these issues, in the quarter century before the US Civil War, many US states enacted protection for the family by making the wife’s assets unassailable in the face of the husband’s debts.60 In the case of marriage breakdown, where the male had absented himself, the courts generally found for the female spouse, and the assets that the woman bought into the marriage were held to be hers. The courts were motivated by welfare concerns for the abandoned family.61 Still, women did not have the right to dispose of their property, or mortgage it in the case of real property.

By the late 19th century, the greater female participation in the labor force precipitated another significant change in the law concerning women’s property rights. There was pressure to permit married women to enter into contracts, the pre-requisite to business activity. A female’s earnings prior to the changes were held to be those of the male spouse. The freeing of women from this obligation encouraged, at the margin, many married women into employment and business activity. Where these laws were enacted, there was an appreciable increase in female-headed businesses.62 In England the major shift in family affairs took place with the passage of The Married Woman’s Property Act in 1871. This law was the outcome of same social and economic pressure that had been building in North America. It was bolstered by the famous, and much-discussed, 1861 essay of John Stuart Mill, The Subjection of Women.63 Prior to the 1871 act, English women appeared to have more, albeit limited, rights of property than their North American sisters, but they had fewer rights over earnings and contracts. Recently, May Beth Combs has analyzed the investment behavior of married women and found that there was a considerable change in attitude once married women were given security over their own property; they increasingly held their assets in personal (movable) as opposed to real estate.64 Many other jurisdictions passed similar laws that established married women in the same legal category as men and single women. However, they typically did not give women claim to assets in the husband’s name which the family accumulated over its lifetime, thus denying the woman the right to her value added. For recognition of that claim, women had to wait another century – long after there was a substantial rise in married women’s labor force participation. As the legal historian Lori Chambers notes when commenting on a Canadian law similar to the 1871 British act, “[it] had done nothing to address the imbalance of economic power within most marriages or to deconstruct the social belief in marital unity, male authority and wifely obedience.”65 In the 20th century, as women’s labor force participation continued to increase and as the divorce rate soared, the number of families headed by a working single mother increased. One consequence of the intersection of social change and the law was that families headed by a single mother were more likely to be poor than other types of families.

7.8 Poverty: One-Parent Families and Elderly Females

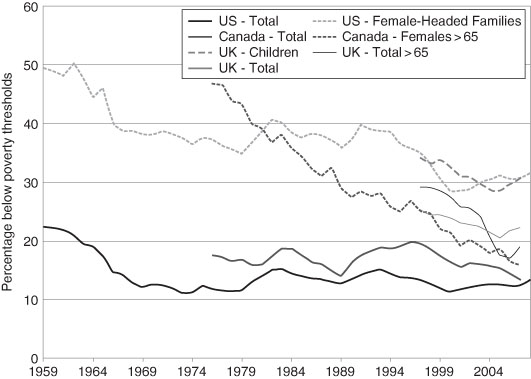

Poverty lowers individual self-worth, shortens the time spent in education, inhibits geographic mobility, leads to poor nutritional standards, causes poor life-style health choices, subjects the individual to more periods of unemployment and is often associated with sub-standard housing. It has many characteristics of a disease and is too easily passed on within families. Many would argue, correctly, that the history of the past 50 years or so has seen the long-run fall of poverty rates in most countries. Most developed countries have at least halved the percentage of their population in poverty. But, even the developed world did not collect evidence on poverty until relatively recently. Definitions of poverty vary widely by country. Any comparison of poverty rates over time across countries is fraught with problems. Nonetheless, Figure 7.3 represents the course of poverty rates for three OECD countries: Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States. Some other countries did better; some other countries did worse. Within countries, some groups fared better than other groups in experiencing poverty declines. But, in all countries, two groups are particularly at a high risk: children and the elderly.

Figure 7.3 Poverty Rates in United States, Canada and the United Kingdom, 1959–2007/8.

Source: US Census data in DeNavas-Walt, Proctor and Smith (2009), Table B-1. Statistics Canada (current) 202082/7; US Historical Statistics, Be 260–411.

Notes: The UK data prior to 2002 exclude Northern Ireland. UK data are based on the 60% threshold of median income.

Poor children are much more likely to come from female-headed single parent families. In all OECD countries today, female-headed single parent families as a percentage of all families with children have more than doubled in the past half century. The second major high-risk group is the elderly. Their increased life expectancy and their growing numbers mean that another high-risk group is increasing proportionately. A focus on these groups gives us a window into the past levels of deprivation. It also informs us of the major social policy initiatives that are on the agenda for action.66

Today in the developed world of OECD countries, no less than 12 % of children live in poverty. However, there is considerable variation. The Scandinavian countries (Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland) register less than 5 % child poverty whereas in four countries of the OECD group (the US, Poland, Mexico and Turkey) about one in every five children lives in poverty.67 For international comparisons, the OECD defines child poverty as those children living in a family whose income is less than one-half of the median family income. (The median income is the income that is found at the mid-point of the population.) It is a relative standard. Some individual countries define poverty by different standards or thresholds based on calculated standards-of-living. European countries use the OECD-like definition but occasionally set different levels. For instance, the United Kingdom uses a 60 % rule; any family with income below 60 % of the median family income is judged as ‘in poverty’. The United States uses a threshold approach where the poverty level is calculated annually by the US Bureau of the Census to set the upper bound on the poverty scale and sets the threshold. This calculation is based on the minimum cost-of-living for individuals and families. It includes such items as: food, clothing, accommodation, the cost of health insurance premiums and transport. Furthermore, it allows for adjustments for the ages of those included and their family relationship – a child in a family does not require the exact same expenditures as an adult. Different thresholds define poverty for families of different compositions and sizes. There is no best solution to the definitional issues, although the threshold definition does provide the flexibility for calculating regional variations in both income and the cost-of-living.68 The same is true of Canada which uses similarly calculated thresholds to define those living with a low income (a euphemism for poverty).69