6 : Oleuropein and Related Secoiridoids: Antioxidant Activity and Sources other than Olea europaea L. (Olive tree)

Abstract

In the present review the broad spectrum of oleuropein activity is described and the need to seek out sources for this biophenol other than Olea europaea L. is stressed. Since except for oleuropein other structurally related secoiridoids may also be found in various Oleaceae species, the structures and, where possible, data on the biological properties of such complex phenolics were reviewed and methodically tabulated. Evidence is given for those species, used as ornamentals, for timber or in folk medicine that could possibly provide extracts rich in oleuropein and related secoiridoids. Our work is expected to stimulate interest in further exploitation of other than the olive tree plant materials as sources for these bioactive compounds so that a larger human population can have a cost effective access to them in the form of dietary supplements or various types of teas.

Key words: Oleuropein, Olea europaea, Oleaceae, Antioxidant activity, Bioactive secoiridoids, Sources of antioxidants, Hydroxytyrosol, Dietary supplements

1. Laboratory of Food Chemistry and Technology, School of Chemistry, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki 541 24 , Greece.

* Corresponding author : E-mail: tsimidou@chem.auth.gr

Introduction

Oleuropein (or oleuropeoside), the ester of 2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl) ethanol with elenolic acid glycoside, is the most characteristic compound of Olea europaea L. (olive tree). This bitter glucoside is present in high amounts in leaves (60-90 mg/g on a dry basis) (Le Tutour & Guedon, 1992), unripe olives (up to 14% of the dry drupe weight) (Amiot et al., 1986) as well as in other parts of the tree. Oleuropein had been detected in the olive fruit by Bourquelot and Vintilesco a century ago but its structure was elucidated later on by Panizzi et al. (1960). Structurally, it is classified to a very specific group of coumarin-like compounds, called secoiridoids. As proposed by Damtoft et al. (1993) and illustrated in Fig 1, it is biosynthesized via deoxyloganic acid. This pathway characterizes exclusively formation of iridoids and secoiridoids of the Oleaceae family (Jensen et al., 2002).

Fig 1. Proposed biosynthetic pathway for oleuropein according to Damtoft et al. (1993)

Oleuropein has been reported to present antioxidant and other biological activities that are summarised in various review articles (Soler-Rivas et al., 2000; Visioli et al., 2002; Boskou et al., 2005; Khan et al., 2007). According to these findings, consumption of oleuropein is expected to have health promoting effects to humans.

To date, olive tree products (mainly table olives and virgin olive oil) are the only edible sources for this secoiridoid and related derivatives. Olive tree cultivation till recently was restricted to the Mediterranean basin, so that only the local population could have access to this beneficial compound through diet. A methodical search in literature revealed that oleuropein, also found in other forms (with slight structural modifications or as part of more complex compounds), is present in various species of the Oleaceae family. The latter comprises 25 genera and ~600 species distributed all over the world from northern temperate to southern subtropical areas (Wallander & Albert, 2000).

As a consequence, the aim of the present review is to describe the broad spectrum of activity of oleuropein, in order to justify the need to seek out sources other than Olea europaea L. Furthermore, to present related secoiridoids so far identified in Oleaceae species, and, where possible, biological properties attributed to them. At last, to give evidence for selected species of this particular family, used as ornamentals, for timber or in folk medicine that could possibly serve as sources of oleuropein and related secoiridoids. Our work is expected to stimulate interest in further exploitation of other than the olive tree species as sources for this group of bioactive compounds so that a larger number of people can have a cost effective access to them.

Antioxidant activity of oleuropein and related secoiridoids

The interest in iridoids, including secoiridoids, has begun almost half a century ago considering a series of chemotaxonomic reviews that summarise the structures of ~1400 members isolated from plants of various families (El-Naggar & Beal, 1980; Boros & Stermitz, 1990 a,b; Dinda et al., 2007 a,b). Among the secoiridoids examined, oleuropein gained the interest of researchers from various fields, who discovered the benefits of virgin olive oil consumption within the frame of the health benefits of the Mediterranean diet (Willett et al., 1995; Shahtamasebi & Shahtamasebi, 2003; Perez-Jimenez et al., 2005).

The principal role of oleuropein in plants is to confer protection against herbivores, certain pests and microbes. Konno et al. (1998, 1999) found out that when the leaf tissue is damaged by herbivores, enzymes (b-specific glucosidase) localized in organelles start to convert the secoiridoid glucoside moiety of oleuropein into a glutaraldehyde (pentane-1,4 dial)-like structure. Protein-aglycone irreversible cross linking leads to the formation of products more or less indigestible and consequently less important as a source of essential amino acids, especially of lysine. Protection from pests, as is Dacus oleae, is achieved due to the high repellency of the glucoside, with result the limited pest oviposition onto the leaves (Lo Scalzo et al., 1994). Kubo et al. (1985) had suggested that the compound that acts as a phytoalexin is a hemiacetal or enal-aldehyde aglycone of oleuropein formed when microorganisms are about to infect the plants.

Except for the contribution of oleuropein to the protection and survival of the plants it seems that it may present various biological properties, contributing to the health benefits of consumption of olive tree products. The most characteristic one is the scavenging of free radicals. A considerable antioxidant activity has been assigned using a chemiluminescent assay (Speroni et al., 1998) or various assays with synthetic radicals like ABTS•+ (Benavente-Garcia et al., 2000), DPPH• (Gordon et al., 2001; Nenadis & Tsimidou, 2002) and DMPD•+ (Briante et al., 2001). Oleuropein activity has been also tested towards reactive species that can be formed in vivo. The latter when produced in high amounts can damage proteins and lipids leading to various degenerative diseases. For example, hydroxyl radicals, which are the most reactive oxygen species and have a deleterious effect in vivo can be effectively neutralised by oleuropein (Chimi et al., 1991; Owen et al., 2000). Visioli et al. (1998) showed that oleuropein enhances immune competent cells in the production of NO, though confirmatory work is needed (De la Puerta et al., 2001). The same group of investigators reported the dose-dependent inhibitory effect on copper sulphate-induced oxidation of LDL at concentrations in the low µM range (Visioli et al., 2002). Similar effect has also been observed in feeding studies with rabbits (Wiseman et al., 1996; Coni et al., 2000). Oleuropein can scavenge superoxide anion generated by either human polymorphonuclear cells or by the xanthine/ xanthine-oxidase system, as well as hypochlorous acid (HOCl) (Visioli et al., 2002). The latter, when generated in vivo by the neutrophil enzyme myeloperoxidase at the site of inflammation can provoke damage to several proteins and enzymes (Aruoma & Halliwel, 1987). Oleuropein has also been found efficient antioxidant in linoleic acid micelles (Chimi et al., 1991), in unilamellar vehicles (Saija et al., 1998) in systems simulating foods (bulk oils and emulsions) (Papadopoulos & Boskou, 1991; Gordon et al., 2001; Nenadis et al., 2005) and in liposomes (Paiva-Martins et al., 2003).

Besides the scavenging of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species other biological properties ascribed to oleuropein are related to the possible protection from cardiovascular disorders (e.g. thrombosis), diabetes, certain cancers, bone damage, and HIV activity. From the early studies of Petkov and Manolov (1972) on the pharmacological analysis of oleuropein, which demonstrated that it can lower the blood pressure, increase the volume rate of coronary flow, relieve arrhythmia and prevent intestinal muscle spasms induced by acetylcholine, nicotine and histamine in various animal models, the interest in the positive effects of oleuropein to cardiovascular disorders is continuous (Zarzuelo et al., 1991; Petroni et al., 1995; Ruiz-Gutierez et al., 1995; Andreadou et al., 2006). The hypoglycemic activity of oleuropein found at 16 mg/kg in animals with alloxan-induced diabetes may result from two mechanisms as suggested by Gonzalez et al. (1992) (a) potential glucose-induced insulin release and (b) increase peripheral uptake of glucose. Recently, Al-Azzawie et al. (2006) suggested that oleuropein not only can be helpful in inhibiting hyperglycemia but it can also inhibit the oxidative stress induced by diabetes. The inhibition of certain disorders can be possibly achieved by the effect of oleuropein on the activity of certain enzymes. An inhibitory effect has been observed on enzymes (cyclooxygenase and 5-lipoxygenase) of the arachidonate cascade and a significant effect on prostaglandin E2 (PGE2)-release (Diaz et al., 2000). It can activate pepsin but inhibit the activity of trypsin, lipase, glycerol dehydrogenase, glycerol- 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, and glycerokinase and, therefore, affect the metabolism of proteins, carbohydrates and lipids (Polzonetti et al., 2004). Saenz et al. (1998) and Park et al. (1999) have demonstrated a cytostatic activity of the glucoside against various tumour cells included in their studies. Recently, the ability to reduce bone loss induced by talc granulomatosis in oestrogen-deficient rats (Puel et al., 2006) and a dose-dependent inhibition on HIV-1 fusion core formation with EC50 values of 66–58 nM, and no detectable toxicity (Lee-Huang, et al., 2007 a,b) broaden the spectrum of positive health effects of oleuropein. Moreover, the anti-microbial activity of oleuropein demonstrated in the past against a broad spectrum of bacteria and fungi (Fleming et al., 1973) was recently investigated against pathogenic bacteria in humans (Bisignano et al., 1999). The antiviral activity has been attributed to various mechanisms of action, which are reviewed in the recent article of Soler-Rivas et al. (2000).

The biological importance of oleuropein is further substantiated by the fact that it is considered as safe. According to Petkov and Manolov (1972) administration of oleuropein (100 to 1000 mg/kg of body weight) to albino mice for seven days provoked no death whilst as no toxic effects were observed the researchers could not determine the LD50 value or adverse effect exposure level.

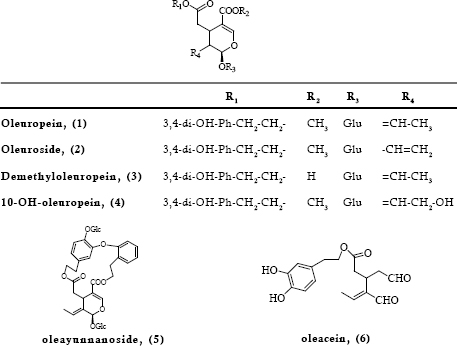

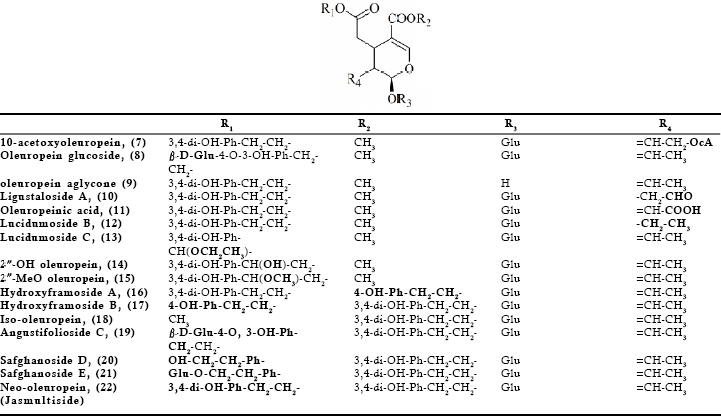

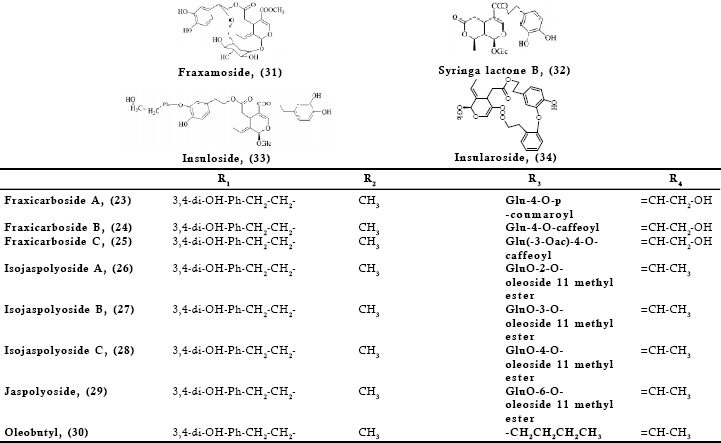

The various biological properties ascribed so far to oleuropein justify and substantiate the need to seek out sources other than the olive tree for this bioactive compound. Since, the secoiridoid may also be found in various Oleaceae species with slight structural modifications or as part of more complex molecules, it was considered useful to present such compounds and where possible to give data on the respective biological properties. In this way more Oleaceae species may serve as sources of bioactive oleuropein and related secoiridoids. The compounds were grouped into those found in the Olea genus (Fig 2) and those found exclusively in other genera of the Oleaceae family (Fig 3). It should be noted that the presence of the compounds of Fig 2 is not restricted only to the genus of Olea.

A close inspection in the literature showed that there is almost no data on the antioxidant or other biological properties of compounds shown in Figs 2 and 3. This could be attributed to the insufficient amounts available to conduct experiments or to difficulties in isolation and instability of certain of the compounds. Information was found for 10-hydroxy-oleuropein (4), which is the most frequently found derivative. As demonstrated, this compound affords protection to red blood cell membrane and therefore resistance to hemolysis induced by the peroxyl radical initiator AAPH (Ouyang et al., 2003). The same effect has been assigned to lucidumoside C (12), (He et al., 2001 a) which can also act as an efficient antiviral agent (Ma et al., 2001). Oleuroside (2), an oleuropein isomer that differs only in the position of a double bond at C8-C10 branch has been found capable of presenting anti-HIV activity (Lee-Huang et al., 2003). Oleacein (6), better known as DHPEA-EAD, seems to be a potent antioxidant in vitro as evidenced by the DPPH• assay after isolation from the leaves of O. europaea (Paiva-Martins & Gordon, 2001). This compound is reported to be a strong angiotensin inhibitor and of low toxicity as evidenced in the brine shrimp (Artemia salina) (LD50 (24h) =969 mg/kg) (Hansen et al., 1996).

Fig 2. Oleuropein and related compounds identified in the genus of Olea

Due to lack of experimental data on the radical scavenging activity of the above derivatives, Nenadis et al. (2005) carried out a theoretical investigation for their prediction in some of the compounds. On the basis of gas phase bond dissociation enthalpy (BDE) values, that are a means of predicting the hydrogen atom donating ability, it was reported that oleuropein (1), demethyloleuropein (3), oleacein (6) and oleuropein aglycone (9) were expected to be almost equally efficient (BDE values 77.7-80.1 kcal/ mol). The authors stressed, however, that in real systems the ultimate performance of the compounds should be also affected by factors such as hydrophobicity and ability of penetrating the biological membranes as a result of molecular weight and configuration. Indeed, this was evidenced in limited surveys. Gordon et al. (2001) when tested the activity of various olive oil compounds including oleuropein and an aglycone isomer with various assays found that the oleuropein aglycone was twice more efficient DPPH• scavenger and twice more potent in the protection of emulsified olive oil triacylglycerols from oxidation at 60 oC. In the case of bulk oil oxidation the aglycone (ten fold less polar in terms of Log P values) was eight times more potent. Menendez et al. (2007) demonstrated a 1.2-2 times higher cytotoxic activity of the aglycone when compared to that of the glucoside in all the breast cancer cell lines employed in their study. The authors ascribed such difference to the greater lipophilicity of the former, which facilitates incorporation in the cell membrane and consequently interaction with other lipids. Similarly, Bao et al. (2007) carrying a computational study in order to complement experimental findings predicted that oleuropein aglycone better binds to HIV-1 fusion protein gp 41 (Binding energy –7.04 kcal/mol) in comparison to oleuropein (Binding energy –4.62 kcal/mol). The authors stated that the presence of a glucosidic residue reduces the binding activity of the compound.

Fig 3. Secoiridoids related to oleuropein identified in Oleaceae genera other than the Olea genus

Fig 3. Secoiridoids related to oleuropein identified in Oleaceae genera other than the Olea genus

.................................... in vitro for the compounds of Figs 2 and 3 does not reflect necessarily behaviour in human body. In vivo the activity of the various compounds may be altered due to molecular transformations during metabolism. For example, glucosidic bonds, present in the majority of them, are prone to hydrolysis under the acidic conditions of the stomach, which favour formation of simpler active compounds (i.e. hydroxytyrosol derivatives or elenolic acid and its various forms) (Edgecombe et al., 2000; Corona et al., 2006). This hypothesis needs further investigation and assessment of bioavailability of individual compounds in order to be established.

Hydroxytyrosol that is formed in the body possesses similar properties to those ascribed to oleuropein as it is documented in parallel studies on the activity of both compounds plus DNA damage protection (Grasso et al., 2007). Furthermore, the former is absorbed nearly completely by humans with a half-life in plasma of 2.4 h (Miro-Casas et al., 2003 a). It is excreted intact or is metabolized into homovanillic alcohol or acid and the corresponding monosulphates or glucuronides derivatives (Caruso et al., 2001; Miro-Casas et al., 2003 b; De la Torre-Carbot et al., 2006).

Elenolic acid also formed, though not expected to act as an antioxidant (Nenadis et al., 2005) has been reported as an efficient antimicrobial agent (Walter et al., 1973).

Occurrence of oleuropein and related secoiridoids in Oleaceae species other than olive tree

Based on chemotaxonomic data oleuropein and related secoiridoids can be found in selected species of the following genera: Chionanthus, Forestiera, Fraxinus, Jasminum, Ligustrum, Nestegis, Olea, Osmanthus, Phillyrea, and Syringa, that is 10 out of 25 genera belonging to Oleaceae family. Some of the species are already used in folk medicine. The genera and corresponding species are presented below in accordance with the classification of Wallander and Albert (2000).

CHIONANTHUS: It is one of the most populated genera of Oleaceae (ca. 100 species), which may thrive in the tropical and subtropical zones of Africa, America, Asia, and Australia (Wallander & Albert, 2000). Apart from an old study on Chionanthus retusus (Iwagawa et al., 1985), research is restricted to C. virginicus L., also known as “fringe tree”. This particular species is used in folk medicine as cholagogue, diuretic and tonic, whilst root bark is used nowadays in homoeopathy for hepatitis and icterus (Gulçin et al., 2007). The bark from the dried roots presenting antioxidant activities is rich in lignans (Boyer et al., 2005; Gulçin et al., 2006) but also abundant in oleuropein, (1) (~4% w/w of root) (Boyer et al., 2005). The methanol and ethyl acetate extract from the root bark of C. virginicus L. has been reported to scavenge free radicals and chelate ferrous ions (Gulçin et al., 2007).

FORESTIERA: It is a genus of fifteen species native in the subtropical N. America, West Indies and S. America. Decoction of the roots and bark from Forestiera acuminata (Michx.) has been used as a health beverage (http://www.pfaf.org/database/plants.php?Forestiera+acuminata). To our knowledge, the only known research on its chemical composition is that of Jensen et al. (2002) who managed to isolate only oleuropein (1) from fresh dried leaves of the particular species.

FRAXINUS: Forty to fifty are the species that belong to this genus and grow mainly in temperate and subtropical regions of the northern hemisphere (Wallander & Albert, 2000). Recently, Kostova and Iossifova, (2007) have reviewed the phytochemistry, ethnopharmacology and the biological activity of extracts and the chemical components of Fraxinus species. The Fraxinus species have been used in the folk medicine for their diuretic and mild purgative effects, for treatment of constipation, dropsy, arthritis, rheumatic pain, cystitis and itching scalp (Calis et al., 1993).

The bark of Fraxinus japonica, which is on the market as the oriental medicine “shin-pi”, has been used since the past as a diuretic, antifebrile and analgestic agent and to treat rheumatism and gout in Japan (Inouye et al., 1975 a; Tsukamoto et al., 1985). The bark of F. americana finds a similar application (Takenaka et al., 2000). Leaves and bark of F. excelsior, native in Europe and Asia, are known as a diuretic and rheumatic remedy and together with extracts from other plants are used as anti-inflammatory and anti-rheumatic drugs (Von Kruedener et al., 1995). The bark and the leaves of F. excelsior and F. ornus are utilized in the Bulgarian and Polish folk medicine to treat various diseases, as is wound healing, diarrhoea and dysentery (Kostova & Iossifova, 2007). The alcoholic extract of F. ornus bark exhibited pronounced antioxidant activity during pure triacylglycerol oxidation of both lard and sunflower oil (Marinova et al., 1994). While, aqueous-ethanolic extracts from F. excelsior could suppress various biochemical model reactions (Meyer et al., 1995). Fraxini Cortex (dry bark of stem or branches of Fraxinus species, including F. rhynchophylla, F. chinensis and F. stylosa) is used in traditional oriental medicine as an astringent against diarrhoea and as an antiphlogistic in ophthalmology for the treatment of conjunctivitis (Kim et al., 2005).

As stated by Kostova and Iossifova (2007) the occurrence of coumarins distinguishes the genus Fraxinus from the other genera in Oleaceae and therefore the genus has always been associated with investigations on the particular compounds. However, an increase in the search for secoiridoid glucosides that are considered major metabolites of the family Oleaceae has been also observed.

Oleuropein (1) has been isolated from various species of the Fraxinus genus. The original articles for most of such species are cited in the above review. In particular, the Fraxinus species of interest are americana, angustifolia, chinensis, excelsior, insularis, japonica, mandshurica, ornus, oxycarba, vetulina and palliside. The same plants are also sources for oleuropein related secoiridoids. For example, (2²R) and (2²S)-2²-hydroxy and methoxy oleuropeins (14, 15), as well as fraxamoside (31) have been isolated and structurally elucidated from F. americana leaves (Takenaka et al., 2000) and 10-hydroxy oleuropein (4) from the leaves of F. uhdei (Shen & Chen, 1995). In the leaves of various species more complex compounds have been identified such as oleuropein esterified to an extra moiety of hydroxytyrosol, namely neo-oleuropein (22) (F. chinensis) (Kuwajima et al., 1992), insuloside (33), insularoside (34) and a glucoside of the latter known also as oleayunnanoside (F. insularis) (Tanahashi et al., 1993, 1998), angustifolioside C (19) and oleobutyl (30) (F. angustifolia) (Calis et al., 1996), fraxicarbosides A (23), B (24), C (25) (F. oxycarba) (Hosny, 1998). Hydroxyframosides A (16) and B (17) were identified in F. ornus bark (Iossifova et al., 1998).

JASMINUM: It is the most populated genus of Oleaceae (ca 200 species) found in tropical and subtropical zones of the Old World (Wallander & Albert, 2000). A variety of medicinal applications for different species is reported in the literature. For example, Jasminum grandiflorum (or J. officinalis, local names jasmine or jatiful) is used as a remedy against various psychiatric disorders, skin diseases and also for the treatment of breast cancer and uterine bleeding (Lis-Balchin et al., 2002; Kolanjiappan & Manoharan, 2005; Manoharan et al., 2006). Literature suggests the use of jasmine as a diuretic and spasmolytic agent, which is given to pregnant women during childbirth (Somanadhan et al., 1998; Lis-Balchin et al., 2002). The leaves of this species are also used in the Indian folk medicine for treating ulcers. The leaves of the same species seem to possess compounds not only with anti-ulcer but also with antioxidant activities as it was found for the 70% ethanolic extract with various assays (DPPH•, O2•-, NO•, reductive ability) (Umamaheswari et al., 2007). The secoiridoid-rich fraction from J. multiflorum leaves and flowers, presented coronary vasodilating and cardiotropic activities (Shen & Chen, 1989). The dried flowers of J. polyanthum have been used as a crude drug, known in Chinese folk medicine as ‘Ye su xin’ to treat orchitis, menorrhalgia and stomachalgia (Tanahashi et al., 1996).

Despite the wide medicinal use of Jasminum species few of them have been investigated with regards to the chemical constituents present. In search of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, Somanadhan et al. (1998) isolated from the aerial parts of J. azoricum an oleuropein derivative, oleacein (6), also found in the leaves of O. europaea and lancea (Hansen et al., 1996). Tanahashi et al. (1999) investigating the dried leaves of J. grandiflorum L. var. grandiflorum (L.) KOBUSKI identified the presence of (2”R)-2”- and (2”S)-2”- methoxyoleuropein (15) together with oleuropein (1) and demethyloleuropein (3). Chen et al. (1991) investigating the chemical constituents of the aerial parts of J. multiflorum, an evergreen shrub that is cultivated as an ornamental plant in Taiwan reported the presence of 10-hydroxyoleuropein (4) and jasmultiside. The structure of the latter given by the authors seems to be the same with the compound called neo-oleuropein, (22). The ethanolic extract from the leaves of J. nitidum yielded among others syrniga lactone B (32) (Shen et al., 2000). Chemical investigation of the leaves and dried flowers from the species J. polyanthum resulted in the isolation of various compounds including oleuropein (1), jaspolyoside (29), isojaspolyoside A (26), B (27), C (28) and a glycopyranoside of oleuropein (8) (Shen et al., 1996 a,b; Tanahashi et al., 1996, 1997).

LIGUSTRUM: 45 species grown in temperate to tropical zones of the Old World, except for Africa belong to this genus (Wallander & Albert, 2000). Many species are used either as a tea or for medicinal purposes. Ku-Ding-Cha, is a well-known Chinese traditional drinking tea having as ingredients various species belonging to different families and genera. From the genus of Ligustrum usual species are Ligustrum pedunculare, L. purpurascens, L. japonicum var. pubescens Koidz., L. robustrum (Roxb.) Bl., (He et al., 1994). Leaves from L. vulgare L. are used for disease prevention or treatment in folk medicine in southern Europe. Methanol extracts from leaves and fruits of L. vulgare. L. scavenged HO• and DPPH•. The effectiveness of the leaf extract to scavenge DPPH• was 1.4-times higher than that observed for the fruit extract (Šersen et al., 2005). The aqueous infusions from the leaves of L. vulgare were efficient towards the DPPH• (Nagy et al., 2006). Pieroni et al. (2000), in their phytopharmacological study on the common privet (L. vulgare) gave detailed data on the uses of the particular species in the Mediterranean basin as medicine to counteract oropharyngea and their anti-inflammatory effects. Nuzhenzi, the fruit of L. lucidum, is prescribed as tonic for kidney and liver in the traditional Chinese medicine (Shi et al., 1998). It was also reported to possess immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, anti-tumor and anti-aging activities while the ethanolic extract from its fruits could inhibit the free radical induced haemolysis in red blood cells (He et al., 2001 a). Ripe berries of L. japonicum Thunb. (Japanese name, Nezumimochi) together with those of L. lucidum Ait. (Japanese name, Tonezumimochi) have been used as a tonic in traditional medicine in Japan (Kuwajima et al., 1989). The plant of L. sinense that is commonly found in the south of China, and known as ‘‘dong-qing’’, ‘‘xiao-la-shu’’ and ‘‘wen-zi-hua’’ is used as a remedy to treat hepatitis and inflammation (Ouyang et al., 2003).

The many medicinal applications of ligrustrum species would evidently lead to identification of the chemical constituents of the various parts of the plants utilized. Kikuchi and Kakkuda (1999), isolated from the leaves of L. lucidum numerous compounds including ligustaloside A (10). On the fruit of the same plant among other constituents oleuropein (1) and lucidumoside B and C (12, 13) were isolated (Ma et al., 2001; He et al., 2001a,b) and oleuropeinic acid (11) (Kikuchi & Yamaguchi, 1985 a). The authors identified the same acid also in the fruit of L. japonicum. Romani et al. (2000) using HPLC investigated the flavonoid and secoiridoid content of the leaves of L. vulgare L. The authors reported the secoiridoids oleuropein (1) and ligustaloside A (10) at levels 4.34 and 40.64 mg/g of dried weight respectively. 10-Hydroxyoleuropein (4) has been found in the fruit of L. obtusifolium (Kikuchi and Yamaguchi, 1982) and in the aerial parts of L. sinense (Ouyang et al., 2003) as well as in the leaves of L. japonicum (Inoue et al., 1982). In the latter species oleuropein (1) and ligustaloside A (10) were also identified.

NESTEGIS: Only five species grown in New Zealand (one species is reported in Hawaii) are assigned to this genus (Wallander & Albert, 2000). Oleuropein (1) was the main component in the leaves of Nestegis sandwicensis (Gray) (Jensen et al., 2002).

OLEA: The genus comprises about 40 species indigenous of the Old World. Olea europaea L. is the most known and intensively investigated tree of Oleaceae species for its chemical components and the biological activity of its extracts (Soler-Rivas et al., 2000; Jensen et al., 2002, Khan et al., 2007). For this reason, as stated in the introduction no emphasis on the particular species will be given. Oleuropein (1) has been found in the leaves of O. verrucosa, the leaves and bark of O. africana and capensis (Tsukamoto et al., 1984; Movsumov, 1994; Nishibe & Sugawara, 2002); From O. yuennanensis (=O. tsoongii) 10-hydroxyoleuropein (4) together with oleayunnanoside, (5) (He et al., 1990) has been reported. Oleacein (6) has been isolated in the past from the leaves of O. lancea (Hansen et al., 1996). The aqueous and ethanolic extracts from the root and stem of O. africana lowered the mean arterial pressure and heart rate in normotensive and deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertensive rats. The authors support that the use of the aqueous extracts could assist the treatment of some forms of hypertension and heart palpitations in humans. This effect may be mediated via beta-adrenergic receptors (Osim et al., 1999).

OSMANTHUS: It is a genus of 30 species mainly found in subtropical regions of East Asia (1-2 species are located in N. America) (Wallander & Albert, 2000). Some of the species have been investigated for their chemical constituents; however, no data exist on any medicinal uses. Recently, Tsai et al. (2007) testing a series of herbal teas including sweet Osmanthus for NO-scavenging and NO-suppressing activities classified it as rather poor NO-suppresser.

Early studies of Inouye et al. (1975 b) on the chemical composition of the leaves of O. fragrans (Japanese name: Kimmokusei) led to the isolation of iridoid glucosides including 10-acetoxyoleuropein (7). From the leaves of O. ilicifolius oleuropein (1), 10-hydroxyoleuropein (4) and 10-acetoxyoleuropein (7) were isolated (Kikuchi & Yamaguchi, 1985 b). The same compounds were also found in the bark of O. asiaticus (Sugiyama et al., 1993). Oleuropein (1) was also isolated from the aerial parts of O. austrocaledonica (Benkrief et al., 1998) and more recently, in the leaves of O. cymosus (Kubba et al., 2005).

PHILLYREA: It is a genus of only two species, Phillyrea latifolia and angustifolia, found in the Mediterranean region and the western Asia (Wallander & Albert, 2000). The smooth anti-inflammatory, diuretic and emmenagogue properties of P. latifolia leaves were known from the ancient times. In recent ethnobotanical literature, the use of the leaves seems to survive still in some areas of South-West Sardinia, Latium and in Morocco as diuretic, spasmolytic (toothache) and diaphoretic (Pieroni et al., 2000). Decoctions of the leaves of P. latifolia leaves are being used in Jordanian folk medicine till nowadays to ameliorate jaundice (Janakat & Al-Merie, 2002). The same authors evaluated the hepatoprotective effect of boiled and non-boiled aqueous extracts using carbon tetrachloride intoxicated rats as an experimental model. The results indicated that after oral administration (4 ml/kg body weight) the bilirubin level and the activity of alkaline phosphatase were both reduced upon treatment with boiled aqueous extract.

Chemical composition of leaves of both species indicated the presence of oleuropein and related derivatives. Thus, Romani et al. (1996) identified in the leaves of in P. angustifolia among others oleuropein (1), demethyl-oleuropein (3), and oleuropein aglycone (9). In the case of P. latifolia, Damtoft et al. (1993) reported the presence of oleuropein (1).

SYRINGA: Twenty are the listed species that are grown in the subtropical areas of Eurasia (Wallander & Albert, 2000). The bark of Syringa afghanica (=S. persica Aitch.) a shrub found in Afghanistan and Pakistan has been used as a tonic and antipyretic in folklore medicine (Takenaka et al., 2002). Yu et al. (1998) studying the anti-HIV-1 enzyme activity and inhibition of HIV-1 replication by natural sources prepared extracts from some plants used as foods and oriental medicines. The authors carried out tests for inhibitory effects on the viral replication, reverse transcriptase, protease and a-glucosidase. The water extract of S. dilatata was among the protease and a-glucosidase-inhibiting samples and showed more than 40% inhibition at a concentration of 100 mg/ml.

Kikuchi et al. (1987, 1988) reported the presence of oleuropein (1), isooleuropein (18), neo-oleuropein (22) as well as syringalactone B (32) in S. vulgaris leaves. Oleuropein (1) was reported in the leaves S. reticulata (Blume) Hara (Kikuchi & Yamauchi, 1987) and later on in the foliage of S. josikaea (Damtoft et al., 1993), the shoots and leaves of both S. vulgaris and josikaea (Damtoft et al., 1995 a,b) the leaves of S. dilatata (Oh et al., 2003) and the leaves of S. Oblata Lindl var. alba (Nenadis et al., 2007). The inner bark of S. vulgaris (Terazawa, 1986), the bark of S. amurensis (Kurkin et al., 1992), as well as the stem bark of S. velutina (Park et al., 1999) were also found to contain oleuropein (1). In S. afghanica dried leaves the presence of oleuropein (1) together with safghanosides D (20), E (21), and isooleuropein (18) has been verified (Takenaka et al., 2002).

Epilogue

The information presented so far and the extended use of Oleaceae species for medicinal purposes justifies why we propose further exploitation of these plant materials as oleuropein sources. Such an idea is enhanced by the fact that other bioactive compounds (e.g. phenylethanoids) are also present. Considering that most of the mentioned investigations were focused on chemotaxonomic purposes we point out the lack of quantitative data that could support further whether or not a particular plant species could serve as a source of oleuropein and related secoiridoids. More work is, thus, needed to trace those species that can be commercialized and used in the preparation of dietary supplements or herbal teas.

References

Al-Azzawie, H.F. and Alhamdani, M.S.S. 2006. Hypoglycemic and antioxidant effect of oleuropein in alloxan-diabetic rabbits. Life Sci. 78: 1371-1377.

Amiot, M.J., Fleuriet, A. and Macheix, J.J. 1986. Importance and evolution of phenolic compounds in olive during growth and maturation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 34: 823-826.

Andreadou, I., Iliodromitis, E.K., Mikros, E., Constantinou, M., Agalias, A., Magiatis, P., Skaltsounis, A.L., Kamber, E., Tsantili-Kakoulidou, A. and Kremastinos, D.Th. 2006. The olive constituent oleuropein exhibits anti-ischemic, antioxidative, and hypolipidemic effects in anesthetized rabbits. J. Nutr. 136: 2213-2219.

Aruoma, O.I. and Halliwell, B. 1987. Action of hypochlorous acid on the antioxidant protective enzymes superoxide dismutase, catalase and glutathione peroxidase. Biochem. J. 248: 973-976.

Bao, J., Zhang, D.W., Zhang, J.Z.H., Lee-Huang, P., Lin Huang, P. and Lee-Huang, S. 2007. Computational study of bindings of olive leaf extract (OLE) to HIV-1 fusion protein gp41. FEBS Lett. 581: 2737-2742.

Benavente-Garcia, O., Castillo, J., Lorente, J., Ortuño, A. and Del Rio, J.A. 2000. Antioxidant activity of phenolics extracted from Olea europaea L. leaves. Food Chem. 68: 457-462.

Benkrief, R., Ranarivelo, Y., Skaltsounis, A.L., Tillequin, F., Koch, M., Pusset, J. and Sevenet, T. 1998. Monoterpene alkaloids, iridoids and phenylpropanoid glycosides from Osmanthus austrocaledonica. Phytochem. 47: 825-832.

Bisignano, G., Tomaino, A., Lo Cascio, R., Crisafi, G., Uccella, N. and Saija, A. 1999. On the in-vitro antimicrobial activity of oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 51: 971-974.

Boros, C.A. and Stermitz, F.R. 1990 a. Iridoids, an updated review, part 1. J. Nat. Prod. 53: 1055-1147.

Boros, C.A. and Stermitz, F.R. 1990 b. Iridoids, an updated review, part 2. J. Nat. Prod. 54: 1173-1246.

Boskou, D., Blekas, G. and Tsimidou, M. 2005. Phenolic compounds in olive oil and olives. Curr. Top. Nutr. Res. 3: 125-136.

Boyer, L., Elias, R., Taoubi, K., Debrauwer, L., Faure, R., Baghdikian, B. and Balansard, G. 2005. Lignans and secoiridoids from the root bark of Chionanthus virginicus: Isolation, identification and HPLC analysis. Phytochem. Anal. 16: 375-379.

Briante, R., La Cara, F., Tonziello, M.P., Febbraio, F. and Nucci, R. 2001. Antioxidant activity of the main bioactive derivatives from oleuropein hydrolysis by hyperthermophilic b-glycosidase. J. Agric. Food Chem. 49: 3198-3203.

Calis, I., Hosny, M. and Lahloub, M.F. 1996. A secoiridoid glucoside from Fraxinus angustifolia. Phytochem. 41: 1557-1562.

Calis, I., Hosny, Khalifa, M. T. and Nishibe, S. 1993. Secoiridoids from Fraxinus angustifolia. Phytochem. 33: 1453-1456.

Caruso, D., Visioli, F., Patelli, R., Galli, C. and Galli, G. 2001. Urinary excretion of olive oil phenols and their metabolites in humans. Metabolism. 50: 1426-1428.

Chen, H.Y. 1991. Jasmultiside, a new secoiridoid glucoside from Jasminum multiflorum. J. Nat. Prod. 54: 1087-1091.

Chimi, H., Cillard, J., Cillard, P. and Rahmani, M. 1991. Peroxyl and hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of some natural phenolic antioxidants. J. Amer. Oil Chem. Soc. 68: 307-312.

Coni, E., Di Benedetto, R., Di Pasquale, M., Masella, R., Modesti, D., Mattei, R. and Carlini, E.A. 2000. Protective effect of oleuropein, an olive oil biophenol, on low density lipoprotein oxidizability in rabbits. Lipids 35: 45-54. Corona, G., Tzounis, X., Assunta Dessi, M., Deiana, M., Debnam, E.S., Visioli, F. and Spencer, J.P.E. 2006.

The fate of olive oil polyphenols in the gastrointestinal tract: Implications of gastric and colonic microflora-dependent biotransformation. Free Radic. Res. 40: 647-658.

Damtoft, S., Franzyk, H. and Jensen, S.R. 1993. Biosynthesis of secoiridoid glucosides in Oleaceae. Phytochem. 34: 1291-1299.

Damtoft, S., Franzyk, H. and Jensen, S.R. 1995 a. Biosynthesis of secoiridoids in Syringa and Fraxinus. Secoiridoid precursors. Phytochem. 40: 773-784.

Damtoft, S., Franzyk, H. and Jensen, S.R. 1995 b. Biosynthesis of secoiridoids in Syringa and Fraxinus. Carbocyclic iridoid precursors. Phytochem. 40: 785-792.

De la Puerta, R., Martínez-Domínguez, M.E., Ruíz-Gutíerrez, V., Flavill, J.A. and Hoult, J.R.S. 2001. Effects of virgin olive oil phenolics on scavenging of reactive nitrogen species and upon nitrergic neurotransmission. Life Sci. 69: 1213-1222.

De la Torre-Carbot, K., Jauregui, O., Castellote, A.I., Lamuela-Raventos, R.M., Covas, M.I., Casals, I. and Lopez-Sabater, M.C. 2006. Rapid high-performance liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry method for qualitative and quantitative analysis of virgin olive oil phenolic metabolites in human low-density lipoproteins. J. Chromatogr. A 1116: 69-75.

Diìaz, A.M., Abad, M.J., Fernandez, L., Recuero, C., Villaescusa, L., Silvan, A.M. and Bermejo, P. 2000. In vitro anti-inflammatory activity of iridoids and triterpenoid compounds isolated from Phillyrea latifolia L. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 23: 1307-1313.

Dinda, B., Debnath, S. and Harigaya, Y. 2007 a. Naturally occurring iridoids. A Review, Part 1. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 55:159-222.

Dinda, B., Debnath, S. and Harigaya, Y. 2007 b. Naturally occurring secoiridoids and bioactivity of naturally occurring iridoids and secoiridoids. A Review, Part 2. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 55: 689-728.

Edgecombe, S.C., Stretch, G.L. and Hayball, P.J. 2000. Oleuropein, an antioxidant polyphenol from olive oil, is poorly absorbed from isolated perfused rat intestine. J. Nutr. 130: 2996-3002.

El-Naggar, L.J. and Beal, J.L. 1980. Iridoids, a review. J. Nat. Prod. 43: 649-707.

Fleming, H.P., Walter, Jr., W.M. and Etchells, J.L. 1973. Antimicrobial properties of oleuropein and products of its hydrolysis from green olives. Applied Microbiol. 26: 777-782.

Gonzalez, M., Zarzuelo, A., Gamez, M.J., Utrilla, M.P., Jimenez, J. and Osuna, I. 1992. Hypoglycemic activity of olive leaf. Planta Med. 58: 513-515.

Gordon, M.H., Paiva-Martins, F. and Almeida, M. 2001. Antioxidant activity of hydroxytyrosol acetate compared with that of other olive oil polyphenols. J. Agric. Food Chem. 49: 2480-2485.

Grasso, S., Siracusa, L., Spatafora, Renis, C.M. and Tringali, C. 2007. Hydroxytyrosol lipophilic analogues: Enzymatic synthesis, radical scavenging activity and DNA oxidative damage protection. Bioorg. Chem. 35: 137-152.

Gulçin, I., Elias, R., Gepdiremen, A. and Boyer, L. 2006. Antioxidant activity of lignans from fringe tree (Chionanthus virginicus L.). Eur. Food Res. Technol. 223: 759-767.

Gulçin, I., Elias, R., Gepdiremen, A., Boyer, L. and Köksal, E. 2007. A comparative study on the antioxidant activity of fringe tree (Chionanthus virginicus L.) extracts. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 6: 410-418.

Hansen, K., Adsersen, A., Christensen, S.B., Jensen, S.R., Nyman, U. and Wagner, S.U. 1996. Isolation of an angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor from Olea europea and Olea lancea. Phytomedicine 2: 319-325.

He, Z.D., Dong, H., Xu, H.X., Ye, W.C., Sun, H.D. and But, P.P.H. 2001 b. Secoiridoid constituents from the fruits of Ligustrum lucidum. Phytochem. 56: 327-330.

He, Z.D., But, P.P.H., Chan, T.W.D., Dong, H., Xu, H.X., Lau, C.P. and Sun, H.D. 2001 a. Antioxidative glucosides from the fruits of Ligustrum lucidum. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 49: 780-784.

He, Z.D., Ueda, S., Akaji, M., Fujita, T., Inoue, K. and Yang, C.R. 1994. Monoterpenoid and phenylethanoid glucosides from Ligustrum pedunculare. Phytochem. 35: 709-716.

He, Z.D., Shi, Z.M. and Yang, C.R. 1990. Studies on some glucosides from Olea yuennanensis Hand.-Mazz. Acta Bot. Sin. 32: 544-550. (cited in Jensen et al., 2002. Phytochem. 60: 213-231). Hosny, M. 1998. Secoiridoid glucosides from Fraxinus oxycarba. Phytochem. 47: 1569-1576.

Inoue, K., Nishioka, T., Tanahashi, T. and Inouye, H. 1982. Three secoiridoid glucosides from Ligustrum japonicum. Phytochem. 21: 2305-2311.

Inouye, H., Inoue, K., Nishioka, T. and Kaniwa, M. 1975 b. Two new iridoid glucosides from Osmantnus fragrans. Phytochem. 14: 2029-2032.

Inouye, H., Nishioka, T. and Kaniwa, M. 1975 a. Glucosides of Fraxinus japonica. Phytochem. 14: 304.

Iossifova, T., Vogler, B. and Kostova, I. 1998. Secoiridoid glucosides from Fraxinus ornus bark. Phytochem.49: 1329-1332.

Iwagawa, T., Takarabe, M. and Hase, T. 1985. On the constituents of Chionanthus retusus. Rep. Fac. Sci. Kagoshima Univ. 18: 49–52. (cited in Jensen et al., 2002. Phytochem. 60: 213-231). Janakat, S. and Al-Merie, H. 2002. Evaluation of hepatoprotective effect of Pistacia lentiscus, Phillyrea latifolia and Nicotiana glauca. J. Ethnopharmacol. 83: 135-138.

Jensen, S.R., Franzyk, H. and Wallander, E. 2002. Chemotaxonomy of the Oleaceae: iridoids as taxonomic markers. Phytochem. 60: 213-231.

Khan, M.Y., Panchal, S., Vyas, N., Butani, A. and Kumar, V. 2007. Olea europaea: A Phyto-pharmacological review. Pharmacog. Rev. 1: 114-118.

Kikuchi, M. and Kakuda, R. 1999. Studies on the constituents of Ligustrum species. XIX. Structures of the iridoid glucosides from the leaves of Ligustrum lucidum Ait. Yakugaku Zasshi/J. Pharmaceut. Soc. Jap. 119: 444-450.

Kikuchi, M. and Yamauchi, Y. 1982. Studies on the constituents of Ligustrum species. V. On the secoiridoids of the fruits of Ligustrum obtusifolium SIEB. Et Zucc. Yakugaku Zasshi/J. Pharmaceut. Soc. Jap.102: 1086-1088.

Kikuchi, M. and Yamauchi, Y. 1985 a. Studies on the constituents of Ligustrum species. XI. On the secoiridoids of the fruits of Ligustrum japonica Thunb. and L. lucidum Ait. Yakugaku Zasshi/J. Pharmaceut. Soc. Jap.105: 142-147.

Kikuchi, M. and Yamauchi, Y. 1985 b. Studies on the constituents of Osmanthus species. III. On the components of the leaves of Osmanthus ilicifolius (Hassk.) Mouillefert. Yakugaku Zasshi/J. Pharmaceut. Soc. Jap. 105: 442-448.

Kikuchi, M. and Yamauchi, Y. 1987. Studies on the constituents of Syringa species. I. Isolation and structures of iridoids and secoiridoids from the leaves of Syringa reticulata (Blume) Hara. Yakugaku Zasshi/J. Pharmaceut. Soc. Jap.107: 23-27.

Kikuchi, M., Yamauchi, Y., Yanase, C. and Nagaoka, I. 1987. Structures of new secoiridoids from the leaves of Syringa vulgaris Linn. Yakugaku Zasshi/J. Pharmaceut. Soc. Jap.107: 245-248.

Kikuchi, M., Yamauchi, Y., Takahashi, Y., Nagaoka, I. and Sugiyama, M. 1988. Structures of new secoiridoids from the leaves of Syringa vulgaris Linn. Yakugaku Zasshi/J. Pharmaceut. Soc. Jap. 108: 355-360.

Kim, H.C., An, R.B., Jeong, G.S., Oh, S.H. and Kim, Y.C. 2005. 1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical scavenging compounds of Fraxini Cortex. Nat. Prod. Sci. 11: 150-154.

Kolanjiappan, K. and Manoharan, S. 2005. Chemopreventive efficacy and anti-lipid peroxidative potential of Jasminum grandiflorum Linn. on 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene-induced rat mammary carcinogenesis. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 19: 687-693.

Konno, K., Hirayama, C., Yasui, H. and Nakanura, M. 1999. Enzymatic activation of oleuropein: A protein cross-linker used as a chemical defence in the privet tree. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96: 9159-9164.

Konno, K., Yasui, H., Hirayama, C. and Shinbo, H. 1998. Glycine protects against strong protein denaturing activity of oleuropein, a phenolic compound in privet leaves. J. Chem. Ecol. 24: 735-751.

Kostova, I. and Iossifova, T. 2007. Chemical components of Fraxinus species. Fitoterapia, 78: 85-106.

Kubba, A., Tillequin, F., Koch, M., Litaudon, M. and Deguin, B. 2005. Iridoids, lignan, and triterpenes from Osmanthus cymosus. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 33: 305-307.

Kubo, I., Matsumoto, A. and Takase, I. 1985. A multichemical defense mechanism of bitter olive Olea europaea (Oleaceae). Is oleuropein a phytoalexin precursor? J. Chem. Ecol. 11: 251-263.

Kurkin, V.A., Evstranova, R.I., Zapesochnaya, G.G. and Pimenova, M.E. 1992. Phenolic compounds of the bark of Syringa amurensis. Chem. Nat. Comp. 28: 511-512.

Kuwajima, H., Matsuuchi, K., Takaishi, K., Inoue, K., Fujita, T. and Inouye, H. 1989. A secoiridoid glucoside from Ligustrum japonicum. Phytochem. 28: 1409-1411.

Kuwajima, H., Morita, M., Takaishi, K., Inoue, K., Fujita, T., He, Z.D. and Yang, C.R. 1992. Secoiridoid, coumarin, and secoiridoid-coumarin glucosides from Fraxinus chinensis. Phytochem. 31: 1277-1280.

Le Tutour, B. and Guedon, D. 1992. Antioxidative activities of Olea europaea leaves and related phenolic compounds. Phytochem. 31: 1173-1178.

Lee-Huang, S., Huang, P.L., Zhang, D., Lee, J.W., Bao, J., Sun, Y., Chang, Y.T., Zhang, J.Z.H. and Huang, P.L. 2007 a. Discovery of small-molecule HIV-1 fusion and integrase inhibitors oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol. Part I. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 354: 872-878.

Lee-Huang, S., Huang, P.L., Zhang, D., Lee, J.W., Bao, J., Sun, Y., Chang, Y.T., Zhang, J.Z.H. and Huang, P.L. 2007 b. Discovery of small-molecule HIV-1 fusion and integrase inhibitors oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol. Part II. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 354: 879-884.

Lee-Huang, S., Li, Z., Huang, P.L., Chang, Y.T. and Huang, P.L. 2003. Anti-HIV activity of olive leaf extract (OLE) and modulation of host cell gene expression by HIV-1infection and OLE treatment. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 307: 1029-1037.

Lis-Balchin, M., Hart, S. and Wan Hang Lo, B. 2002. Jasmine absolute (Jasminum grandiflora L.) and its mode of action on guinea-pig ileum in vitro. Phytother. Res. 16: 437-439.

Lo Scalzo, R., Scarpati, M.L., Verzegnassi, B. and Vita, G. 1994. Olea europaea chemicals repellent to Dacus oleae females. J. Chem. Ecol. 20: 1813-1823.

Ma, S.C., He, Z.D., Deng, X.L., But, P.P.H., Ooi, V.E.C., Xu, H.X., Lee, S. H.S. and Lee, S.F. 2001. In vitro evaluation of secoiridoid glucosides from the fruits of Ligustrum lucidum as antiviral agents. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 49: 1471-1473.

Manoharan, S., Panjamurthy, K., Vasudevan, K., Sasikumar, D. and Kolanjiappan, K. 2006. Protective effect of Jasminum grandiflorum Linn. On DMBA-induced chromosomal aberrations in bone marrow of wintstar rats. Int. J. Pharmacol. 2: 406-410.

Marinova, E.M., Yanishlieva, N.V. and Kostova, I.N. 1994. Antioxidative action of the ethanolic extract and some hydroxycoumarins of Fraxinus ornus bark. Food Chem. 51: 125-132.

Menendez, J.A., Vazquez-Martin, A., Colomer, R., Brunet, J., Carrasco-Pancorbo, A., Garcia-Villalba, R., Fernandez-Gutierrez, A. and Segura-Carretero, A. 2007. Olive oil’s bitter principle reverses acquired autoresistance to trastuzumab (Herceptin™) in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 7: 80-98.

Meyer, B., Schneider, W. and Elstner, E.F. 1995. Antioxidative properties of alcoholic extracts from Fraxinus excelsior, Populus tremula and Solidago virgaurea. Arzneim. Forsch. 45: 174-176.

Miro-Casas, E., Covas, M.I., Farre, M., Fito, M., Ortuño, J., Weinbrenner, T., Roset, P. and de la Torre, R., 2003 a. Hydroxytyrosol disposition in humans. Clin. Chem. 49: 945-952.

Miro-Casas, E., Covas, M.I., Fito, M., Farre-Albadalejo, M., Marrugat, J. and de la Torre, R. 2003 b. Tyrosol and hydroxytyrosol are absorbed from moderate and sustained doses of virgin olive oil in humans. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 57: 186–190.

Movsumov, I.S. 1994. Components of the leaves of Olea verrucosa. Chem. Nat. Prod. 30: 626.

Nagy, M., Spilkova, J., Vrchovska, V., Kontšekova, Z., Šersen, F., Mučaji, P. and Grančai, D. 2006. Free radical scavenging activity of different extracts and some constituents from the leaves of Ligustrum vulgare and L. delavayanum. Fitoterapia 77: 395-397.

Nenadis, N. and Tsimidou, M. 2002. Observations on the estimation of scavenging activity of phenolic compounds using rapid 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) test. J. Amer. Oil Chem. Soc. 79: 1191-1195.

Nenadis, N., Vervoort, J., Boeren, S. and Tsimidou, M.Z. 2007. Syringa oblata Lindl var. alba as a source of oleuropein and related compounds. J. Sci. Food Agric. 87: 160-166.

Nenadis, N., Wang, L.F., Tsimidou, M. and Zhang, H.Y. 2005. Radical scavenging potential of phenolic compounds encountered in O. europaea products as indicated by calculation of bond dissociation enthalpy and ionization potential values. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53: 295-299.

Nishibe, S. and Sugawara, S. 2002. Phenolic compounds from leaves of Olea africana and O. capensis. Nat Med. 56:18.

Oh, H., Ko, E.K., D.H., Kim, Jang, K.K., Park, S.E., Lee, H.S., and Kim, Y.C. 2003. Secoiridoid glucosides with free radical scavenging activity from the leaves of Syringa dilatata. Phytother. Res. 17: 417-419.

Osim, E.E., Mbajiorgu, E.F., Mukarati, G., Vaz, R.F., Makufa, B., Munjeri, O. and Musabayane, C.T. 1999. Hypotensive effect of crude extract Olea africana (Oleaceae) in normo and hypertensive rats. Cent. Afr. J. Med. 45: 269-274.

Ouyang, M.A., He, Z.D. and Wu, C.L. 2003. Anti-oxidative activity of glycosides from Ligustrum sinense. Nat. Prod. Res. 17: 381-387.

Owen, R.W., Giacosa, A., Hull, W.E., Haubner, R., Würtele, G., Spiegelhalder, B. and Bartsch, H. 2000. Olive-oil consumption and health: the possible role of antioxidants. Lancet Oncol. 1: 107-112.

Paiva-Martins, F. and Gordon, M.H. 2001. Isolation and characterization of the antioxidant component 3,4-dihydroxyphenylethyl 4-formyl-3-formylmethyl-4-hexenoate from olive (Olea europaea) leaves. J. Agric. Food Chem. 49: 4214-4219.

Paiva-Martins, F., Gordon, M.H. and Gameiro, P. 2003. Activity and location of olive oil phenolic antioxidants in liposomes. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 124: 23-36.

Panizzi, L.M., Scarpati, J.M. and Oriente, E.G. 1960. Constituzione della oleuropeina, glucoside, glucoside amaro e ad azione ipotensiva dell olivo. Nota II. Gazz. Chim. Ital. 90: 1449-1485.

Papadopoulos, G. and Boskou, D. 1991. Antioxidant effect of natural phenols on olive oil. J. Amer. Oil Chem. Soc. 68: 669-671.

Park, H.J., Lee, M.S., Lee, K.T., Sohn, I.C., Han, Y.N. and Miyamoto, K. 1999. Studies on constituents with cytotoxic activity from the stem bark of Syringa velutina. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 47: 1029-1031.

Perez-Jimenez, F., Alvarez De Cienfuegos, G., Badimon, L., Barja, G., Battino, M., Blanco, A., Bonanome, A., Colomer, R., Corella-Piquer, D., Covas, I., Chamorro-Quiros, J., Escrich, E., Gaforo, J.J., Garcia Luna, P.P., Hidalgo, L., Kafatos, A., Kris-Etherton, P.M., Lairon, D., Lamuela-Raventos, R., Lopez-Miranda, J., Lopez-Segura, F., Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A., Mata, P., Mataix, J., Ordovas, J., Osada, J., Pacheco-Reyes, R., Perucho, M., Pineda-Priego, M., Quiles, J.L., Ramirez-Tortosa, M.C., Ruiz-Gutierrez, V., Sanchez-Rovira, P., Solfrizzi, V., Soriguer-Escofet, F., De La Torre-Fornell, R., Trichopoulos, A., Villalba-Montoro, J.M., Villar-Ortiz, J.R. and Visioli, F. 2005. International conference on the healthy effect of virgin olive oil. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 35: 421-424.

Petkov, V. and Manolov, P. 1972. Pharmacological analysis of the iridoid oleuropein. Arzneim. Forsch. 22: 1476-1486.

Petroni, A., Blasevich, M., Salami, M., Papini, N., Montedoro, G.F. and Galli, C. 1995. Inhibition of platelet aggregation and eicosanoid production by phenolic components of olive oil. Thromb. Res. 78: 151-160.

Pieroni, A., Pachaly, P., Huang, Y., Van Poel, B. and Vlietinck, A.J. 2000. Studies on anti-complementary activity of extracts and isolated flavones from Ligustrum vulgare and Phillyrea latifolia leaves (Oleaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 70: 213-217.

Polzonetti, V., Egidi, D., Vita, A., Vincenzetti, S. and Natalini, P. 2004. Involvement of oleuropein in (some) digestive metabolic pathways. Food Chem. 88: 11-15.

Puel, C., Mathey, J., Agalias, A., Kati-Coulibaly, S., Mardon, J., Obled, C., Davicco, M.J., Lebecque, P., Horcajada, M.N., Skaltsounis, A.L. and Coxam, V. 2006. Dose–response study of effect of oleuropein, an olive oil polyphenol, in an ovariectomy/ inflammation experimental model of bone loss in the rat. Clin. Nutr. 25: 859-868.

Romani, A., Baldi, A., Mulinacci, N., Vincieri, F.F. and Tattini, M. 1996. Extraction and identification procedures of polyphenolic compounds and carbohydrates in phillyrea (Phillyrea angustifolia L.) leaves. Chromatogr. 42: 571-577.

Romani, A.,Pinelli, P., Mulinacci, N., Vincieri, F.F., Gravano, E. and Tattini, M. 2000. HPLC analysis of flavonoids and secoiridoids in leaves of Ligustrum vulgare L. (Oleaceae). J. Agric. Food Chem. 48: 4091-4096.

Ruiz-Gutierrez, V., Muriana, F.J.G., Maestro, R. and Graciani, E. 1995. Oleuropein on lipid and fatty acid composition of rat heart. Nutr. Res. 15: 37-51.

Saenz, M.T., Garcia, M.D., Ahumada, M.C. and Ruiz, V. 1998. Cytostatic activity of some compounds from the unsaponifiable fraction obtained from virgin olive oil. Il Farmaco. 53: 448-449.

Saija, A., Trombetta, D., Tomaino, A., Lo Cascio, R., Princi, P., Uccella, N., Bonina, F. and Castelli, F. 1998. In vitro evaluation of the antioxidant activity and biomembrane interaction of the plant phenols oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol. Int. J. Pharm. 166: 123- 133. Šersen, F., Mučaji, P., Grančai, D. and Nagy, M. 2005. Antioxidative properties of methanol extracts from leaves and fruits of Ligustrum vulgare L. Acta Facult. Pharm. Univ. Comenianae 52: 204-209.

Shahtahmasebi, S. and Shahtahmasebi, S. 2003. A case report of possible health benefits of extra virgin olive oil. Sci. World J. 3:1265-1271.

Shen, Y.C. and Chen, C.H. 1989. Novel secoiridoid lactones from Jasminum multiflorum. J. Nat. Prod. 52: 1060-1070.

Shen, Y.C. and Chen, C.Y. 1995. Additional secoiridoid glucosides from Fraxinus uhdei. Planta Med. 61: 281-283.

Shen, Y.C., Chen, C.F., Gao, J., Zhao, C. and Chen, C.Y. 2000. Secoiridoid glycosides from some selected Jasminum spp. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 47: 367-372.

Shen, Y.C., Lin, S.L. and Chein, C.C. 1996 b. Jaspolyside, a secoiridoid glucoside from Jasminum polyanthum. Phytochem. 42: 1629-1631.

Shen, Y.C., Lin, S.L., Hsieh, P.W. and Chein, C.C. 1996 a. Secoiridoid glucosides from Jasminum polyanthum. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 43: 171-176.

Shi, L., Ma, Y. and Cai, Z. 1998. Quantitative determination of salidroside and specnuezhenide in the fruits of Ligustrum lucidum Ait by high performance liquid chromatography. Biomed. Chromatogr. 12: 27-30.

Soler-Rivas, C., Espin, J.C. and Wichers, H.J. 2000. Oleuropein and related compounds. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 80: 1013-1023.

Somanadhan, B., Smitt, U.W., George, V., Pushpangadan, P., Rajasekharan, S., Duus, J. Ø., Nyman, U., Olsen, C.E. and Jaroszewski, J. 1998. Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors from Jasminum azoricum and Jasminum grandiflorum. Planta Med. 64: 246-250.

Speroni, E., Guerra, M.C., Minghetti, A., Crespi-Perellino, N., Pasini, P., Piazza, F. and Roda, A. 1998. Oleuropein evaluated in vitro and in vivo as an antioxidant. Phytother. Res. 12: s98–s100.

Sugiyama, M., Machida, K., Matsuda, N. and Kikuchi, M. 1993. A secoiridoid glycoside from Osmanthus asiaticus. Phytochem. 34: 1169-1170.

Takenaka, Y., Okazaki, N., Tanahashi, T., Nagakura, N. and Nishi, T. 2002. Secoiridoid and iridoid glucosides from Syringa afghanica. Phytochem. 59: 779-787.

Takenaka, Y., Tanahashi, T., Shintaku, M., Sakai, T. and Nagakura, N., Parida. 2000. Secoiridoid glucosides from Fraxinus americana. Phytochem. 55: 275-284.

Tanahashi, T., Shimada, A., Nagakura, N., Inoue, K., Kuwajima, H., Takaishi, K., Chen, C.C., He, Z.D. and Yang, C.R. 1993 Isolation of oleayunnanoside from Fraxinus insularis and revision of its structure to insularoside-6”‘-O-ß-D-glucoside. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 41: 1649-1651.

Tanahashi, T., Parida, Takenaka, Y., Nagakura, N., Inoue, K., Kuwajima, H. and Chen, C.C. 1998. Four secoiridoid glucosides from Fraxinus insularis. Phytochem. 49: 1333-1337.

Tanahashi, T., Sakai, T., Takenaka, Y., Nagakura, N. and Chen, C.C. 1999. Structure elucidation of two secoiridoid glucosides from Jasminum officinale L. var. grandiflorum (L.). Kobuski. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 47: 1582-1586.

Tanahashi, T., Takenaka, Y. and Nagakura, N. 1996. Two dimeric secoiridoid glucosides from Jasminum polyanthum. Phytochem. 41: 1341-1345.

Tanahashi, T., Takenaka, Y., Akimoto, M., Okuda, A., Kusunoki, Y., Suekawa, C. and Nagakura, N. 1997. Six secoiridoid glucosides from Jasminum polyanthum. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 45: 367-372.

Terazawa, M. 1986. Phenolic compounds in living tissues of woods VI. Ligustroside and oleuropein in Fraxinus mandshurica var. japonica Maxim. and Syringa vulgaris L. and their seasonal variation in them. Res. Bull. Coll. Exp. Forest. 43: 109-126.

Tsai, P.J., Tsai, T.H., Yu, C.H. and Ho, S.C. 2007. Comparison of NO-scavenging and NO-suppressing activities of different herbal teas with those of green tea. Food Chem. 103: 181-187.

Tsukamoto, H., Hisada, S. and Nishibe, S. 1985. Coumarins from the bark of Fraxinus japonica and Fraxinus mandshurica var. japonica. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 33: 4069-4073.

Tsukamoto, H., Hisada, S. and Nishibe, S. 1984. Coumarin and secoiridoid glucosides from bark of Olea africana and Olea capensis. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 33: 396-399.

Umamaheswari, M., Asokkumar, K., Rathidevi, R., Sivashanmugam, A.T., Subhadradevi, V. and Ravi, T.K. 2007. Antiulcer and in vitro antioxidant activities of Jasminum grandiflorum L. J. Ethnopharmacol. 110: 464-470.

Visioli, F., Galli, C., Galli, G. and Caruso, D. 2002. Biological activities and metabolic fate of olive oil phenols. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 104: 677-684.

Visioli, F., Bellosta, S. and Galli, C. 1998. Oleuropein, the bitter principle of olives, enhances nitric oxide production by mouse macrophages. Life Sci. 62: 541-546.

Von Kruedener, S., Schneider, W. and Elstner, E.F. 1995. A combination of Populus tremula, Solidgo virgaurea and Fraxinus excelsior as an anti-inflammatory and antirheumatic drug. A short review. Arzneim. Forsch. 45: 169-171.

Wallander, E. and Albert, V.A. 2000. Phylogeny and classification of Oleaceae based on RPS 16 and TRNL-F sequence data. Am. J. Bot. 87: 1827-1841.

Walter, Jr W.M., Fleming, H.P. and Etchells, J.L. 1973. Preparation of antimicrobial compounds by hydrolysis of oleuropein from green olives. Applied Microbiol. 26: 773-776.

Willett, W.C., Sacks, F., Trichopoulou, A., Drescher, G., Ferro-Luzzi, A., Helsing, E. and Trichopoulos, D. 1995. Mediterranean diet pyramid: A cultural model for healthy eating. Amer. J. Clin. Nutr. 61: 1402-s1406.

Wiseman, S.A., Mathot, J.N.N.J., de Fouw, N.J. and Tijburg, L.B.M. 1996. Dietary non-tocopherol antioxidants present in extra virgin olive oil increase the resistance of low-density lipoproteins to oxidation in rabbits. Atheroscler. 120: 15-23.

Yu, Y.B., Park, J.C., Lee, J.H., Kim, G.E., Jo, S.K., Byun, M.W., Miyashiro, H. and Hattori, M. 1998. Screening of some plant extracts for inhibitory effects on HIV-1 and its essential enzymes. Korean J. Pharmacog. 29: 338-346.

Zarzuelo, A., Duarte, J., Jimenez, J., Gonzalez, M. and Utrilla, M.P. 1991. Vasodilator effect of olive leaf. Planta Med. 57: 417-419.