‘A steadily increasing proportion of capital in industry,’ Hilferding writes, ‘does not belong to the industrialists who employ it. They obtain the use of it only through the medium of the banks, which, in relation to them, represent the owners of the capital. On the other hand, the bank is forced to keep an increasing share of its funds engaged in industry. Thus, to an increasing degree the bank is being transformed into an industrial capitalist. This bank capital, i.e., capital in money form which is thus really transformed into industrial capital, I call “finance capital.” … Finance capital is capital controlled by banks and employed by industrialists.’

This definition is incomplete in so far as it is silent on one extremely important fact: the increase of concentration of production and of capital to such an extent that it leads, and has led, to monopoly. But throughout the whole of his work, and particularly in the two chapters which precede the one from which this definition is taken, Hilferding stresses the part played by capitalist monopolies.

The concentration of production; the monopoly arising therefrom; the merging or coalescence of banking with industry – this is the history of the rise of finance capital and what gives the term ‘finance capital’ its content.

We now have to describe how, under the general conditions of commodity production and private property, the ‘domination’ of capitalist monopolies inevitably becomes the domination of a financial oligarchy. It should be noted that the representatives of German bourgeois science – and not only of German science – like Riesser, Schulze-Gaevernitz, Liefmann and others are all apologists of imperialism and of finance capital. Instead of revealing the ‘mechanics’ of the formation of an oligarchy, its methods, its revenues ‘innocent and sinful,’ its connections with parliaments, etc., they conceal, obscure and embellish them. They evade these ‘vexed questions’ by a few vague and pompous phrases: appeals to the ‘sense of responsibility’ of bank directors, praising ‘the sense of duty’ of Prussian officials; by giving serious study to petty details, to ridiculous bills of parliament – for the ‘supervision’ and ‘regulation’ of monopolies; by playing with theories, like, for example, the following ‘scientific’ definition, arrived at by Professor Liefmann: ‘Commerce is an occupation having for its object: collecting goods, storing them and making them available.’ (The Professor’s boldface italics.) From this it would follow that commerce existed in the time of primitive man, who knew nothing about exchange, and that it will exist under socialism!

But the monstrous facts concerning the monstrous rule of the financial oligarchy are so striking that in all capitalist countries, in America, France and Germany, a whole literature has sprung up, written from the bourgeois point of view, but which, nevertheless, gives a fairly accurate picture and criticism – petty-bourgeois, naturally – of this oligarchy.

The ‘holding system,’ to which we have already briefly referred above, should be placed at the corner-stone. The German economist, Heymann, probably the first to call attention to this matter, describes it in this way:

‘The head of the concern controls the parent company; the latter reigns over the subsidiary companies which in their turn control still other subsidiaries. Thus, it is possible with a comparatively small capital to dominate immense spheres of production. As a matter of fact, if holding 50 per cent of the capital is always sufficient to control a company, the head of the concern needs only one million to control eight millions in the second subsidiaries. And if this “interlocking” is extended, it is possible with one million to control sixteen, thirty-two or more millions.’

Experience shows that it is sufficient to own 40 per cent of the shares of a company in order to direct its affairs, since a certain number of small, scattered shareholders find it impossible, in practice, to attend general meetings, etc. The ‘democratisation’ of the ownership of shares, from which the bourgeois sophists and opportunist ‘would-be’ Social-Democrats expect (or declare that they expect) the ‘democratisation of capital,’ the strengthening of the role and significance of small-scale production, etc., is, in fact, one of the ways of increasing the power of financial oligarchy. Incidentally, this is why, in the more advanced, or in the older and more ‘experienced’ capitalist countries, the law allows the issue of shares of very small denomination. In Germany, it is not permitted by the law to issue shares of less value than one thousand marks, and the magnates of German finance look with an envious eye at England, where the issue of one-pound shares is permitted. Siemens, one of the biggest industrialists and ‘financial kings’ in Germany, told the Reichstag on June 7, 1900, that ‘the one-pound share is the basis of British imperialism.’ This merchant has a much deeper and more ‘Marxian’ understanding of imperialism than a certain disreputable writer, generally held to be one of the founders of Russian Marxism, who believes that imperialism is a bad habit of a certain nation. …

But the ‘holding system’ not only serves to increase enormously the power of the monopolists; it also enables them to resort with impunity to all sorts of shady tricks to cheat the public, for the directors of the parent company are not legally responsible for the subsidiary companies, which are supposed to be ‘independent,’ and through the medium of which they can ‘pull off’ anything. Here is an example taken from the German review, Die Bank, for May 1914:

‘The Spring Steel Company of Kassel was regarded some years ago as being one of the most profitable enterprises in Germany. Through bad management its dividends fell within the space of a few years from 15 per cent to nil. It appears that the Board, without consulting the shareholders, had loaned six million marks to one of the subsidiary companies, the Hassia, Ltd., which had a nominal capital of only some hundreds of thousands of marks. This commitment, amounting to nearly treble the capital of the parent company, was never mentioned in its balance sheets. This omission was quite legal, and could be kept up for two whole years because it did not violate any provision of company law. The chairman of the Supervisory Board, who as the responsible head had signed the false balance sheets, was, and still is, the president of the Kassel Chamber of Commerce. The shareholders only heard of the loan to the Hassia, Ltd., long afterwards, when it had long been proved to have been a mistake’ (this word the writer should have put in quotation marks), ‘and when Spring Steel shares had dropped nearly 100 points, because those in the know had got rid of them. …

‘This typical example of balance-sheet jugglery, quite common in joint stock companies, explains why their Boards of Directors are more willing to undertake risky transactions than individual dealers. Modern methods of drawing up balance sheets not only make it possible to conceal doubtful undertakings from the average shareholder, but also allow the people most concerned to escape the consequence of unsuccessful speculation by selling their shares in time while the individual dealer risks his own skin in everything he does.

‘The balance sheets of many joint stock companies put us in mind of the palimpsests of the Middle Ages from which the visible inscription had first to be erased in order to discover beneath it another inscription giving the real meaning of the document.’ (Palimpsests are parchment documents from which the original inscription has been obliterated and another inscription imposed.)

‘The simplest and, therefore, most common procedure for making balance sheets indecipherable is to divide a single business into several parts by setting up subsidiary companies – or by annexing such. The advantages of this system for various objects – legal and illegal – are so evident that it is now quite unusual to find an important company in which it is not actually in use.’

As an example of an important monopolist company widely employing this system, the author quotes the famous General Electric Company (Allgemeine Elektrizitäts Gesellschaft – A.E.G.) to which we shall refer below. In 1912, it was calculated that this company held shares in from 175 to 200 other companies, controlling them, of course, and thus having control of a total capital of 1,500,000,000 marks!

All rules of control, the publication of balance sheets, the drawing up of balance sheets according to a definite form, the public auditing of accounts, etc., the things about which well-intentioned professors and officials – that is, those imbued with the good intention of defending and embellishing capitalism – discourse to the public, are of no avail. For private property is sacred, and no one can be prohibited from buying, selling, exchanging or mortgaging shares, etc.

The extent to which this ‘holding system’ has developed in the big Russian banks may be judged by the figures given by E. Agahd, who was for fifteen years an official of the Russo-Chinese Bank and who, in May 1914, published a book, not altogether correctly entitled Big Banks and the World Market. The author divides the big Russian banks into two main categories: a) banks that come under a ‘holding system,’ and b) ‘independent’ banks – ‘independence,’ however, being arbitrarily taken to mean independence of foreìgn banks. The author divides the first group into three sub-groups: 1) German participation, 2) British participation, and 3) French participation, having in view the ‘participation’ and domination of the big foreign banks of the particular country mentioned. The author divides the capital of the banks into ‘productively’ invested capital (in industrial and commercial undertakings), and ‘speculatively’ invested capital (in Stock Exchange and financial operations), assuming, from his petty-bourgeois reformist point of view, that it is possible, under capitalism, to separate the first form of investment from the second and to abolish the second form.

Here are the figures he supplies:

Bank Assets

(According to reports for October-November, 1913, in millions of rubles)

According to these figures, of the approximately four billion rubles making up the ‘working’ capital of the big banks, more than three-fourths, more than three billion, belonged to banks which in reality were only ‘subsidiary companies’ of foreign banks, and chiefly of the Paris banks (the famous trio: Union Parisien, Paris et Pays-Bas and Société Générale), and of the Berlin banks (particularly the Deutsche Bank and Disconto-Gesellschaft). Two of the most important Russian banks, the Russian Bank for Foreign Trade and the St. Petersburg International Commercial, between 1906 and 1912 increased their capital from 44,000,000 to 98,000,000 rubles, and their reserve from 15,000,000 to 39,000,000 ‘employing three-fourths German capital.’ The first belongs to the Deutsche Bank group and the second to the Disconto-Gesellschaft. The worthy Agahd is indignant at the fact that the majority of the shares are held by the Berlin banks, and that, therefore, the Russian shareholders are powerless. Naturally, the country which exports capital skims the cream: for example, the Deutsche Bank, while introducing the shares of the Siberian Commercial Bank on the Berlin market, kept them in its portfolio for a whole year, and then sold them at the rate of 193 for 100, that is, at nearly twice their nominal value, ‘earning’ a profit of nearly 6,000,000 rubles, which Hilferding calls ‘promoters’ profits.’

Our author puts the total ‘resources’ of the principal St. Petersburg banks at 8,235,000,000 rubles, about 8¼ billions and the ‘holdings,’ or rather, the extent to which foreign banks dominated them, he estimates as follows: French banks, 55 per cent; English, 10 per cent; German, 35 per cent. The author calculates that of the total of 8,235,000,000 rubles of functioning capital, 3,687,000,000 rubles, or over 40 per cent, fall to the share of the syndicates, Produgol and Prodamet – and the syndicates in the oil, metallurgical and cement industries. Thus, the merging of bank and industrial capital has also made great strides in Russia owing to the formation of capitalist monopolies.

Finance capital, concentrated in a few hands and exercising a virtual monopoly, exacts enormous and ever-increasing profits from the floating of companies, issue of stock, state loans, etc., tightens the grip of financial oligarchies and levies tribute upon the whole of society for the benefit of monopolists. Here is an example, taken from a multitude of others, of the methods of ‘business’ of the American trusts, quoted by Hilferding: in 1887, Havemeyer founded the Sugar Trust by amalgamating fifteen small firms, whose total capital amounted to $6,500,000. Suitably ‘watered,’ as the Americans say, the capital of the trust was increased to $50,000,000. This ‘over-capitalisation’ anticipated the monopoly profits, in the same way as the United States Steel Corporation anticipated its profits by buying up as many iron fields as possible. In fact, the Sugar Trust set up monopoly prices on the market, which secured it such profits that it could pay 10 per cent dividend on capital ‘watered’ sevenfold, or about 70 per cent on the capital actually invested at the time of the creation of the trust! In 1909, the capital of the Sugar Trust was increased to $90,000,000. In twenty-two years, it had increased its capital more than tenfold.

In France the role of the ‘financial oligarchy’ (Against the Financial Oligarchy in France, the title of the well-known book by Lysis, the fifth edition of which was published in 1908) assumed a form that was only slightly different. Four of the most powerful banks enjoy, not a relative, but an ‘absolute monopoly’ in the issue of bonds. In reality, this is a ‘trust of the big banks.’ And their monopoly ensures the monopolist profits from bond issues. Usually a country borrowing from France does not get more than 90 per cent of the total of the loan, the remaining 10 per cent goes to the banks and other middlemen. The profit made by the banks out of the Russo-Chinese loans of 400,000,000 francs amounted to 8 per cent; out of the Russian (1904) loan of 800,000,000 francs the profit amounted to 10 per cent; and out of the Moroccan (1904) loan of 62,500,000 francs, to 18.75 per cent. Capitalism, which began its development with petty usury capital, ends its development with gigantic usury capital. ‘The French,’ says Lysis, ‘are the usurers of Europe.’ All the conditions of economic life are being profoundly modified by this transformation of capitalism. With a stationary population, and stagnant industry, commerce and shipping, the ‘country’ can grow rich by usury. ‘Fifty persons, representing a capital of 8,000,000 francs, can control 2,000,000,000 francs deposited in four banks.’ The ‘holding system,’ with which we are already familiar, leads to the same result. One of the biggest banks, the Société Générale, for instance, issues 64,000 bonds for one of its subsidiary companies, the Egyptian Sugar Refineries. The bonds are issued at 150 per cent, i.e., the bank gaining 50 centimes on the franc. The dividends of the new company are then found to be fictitious. The ‘public’ lost from 90 to 100 million francs. One of the directors of the Société Générale was a member of the board of directors of the Egyptian Sugar Refineries. Hence it is not surprising that the author is driven to the conclusion that ‘the French Republic is a financial monarchy’; ‘it is the complete domination of the financial oligarchy; the latter controls the press and the government.’

The extraordinarily high rate of profit obtained from the issue of securities, which is one of the principal functions of finance capital, plays a large part in the development and consolidation of the financial oligarchy.

‘There is not within the country a single business of this type that brings in profits even approximately equal to those obtained from the flotation of foreign loans,’ says the German magazine, Die Bank.

‘No banking operation brings in profits comparable with those obtained from the issue of securities!’

According to the German Economist, the average annual profits made on the issue of industrial securities were as follows:

| Per cent | Per cent | ||

| 1895 | 38.6 | 1898 | 67.7 |

| 1896 | 36.1 | 1899 | 66.9 |

| 1897 | 66.7 | 1900 | 55.2 |

‘In the ten years from 1891 to 1900, more than a billion marks of profits were “earned” by issuing German industrial securities.’

While, during periods of industrial boom, the profits of finance capital are disproportionately large, during periods of depression, small and unsound businesses go out of existence, while the big banks take ‘holdings’ in their shares, which are bought up cheaply or in profitable schemes for their ‘reconstruction’ and ‘reorganisation.’ In the ‘reconstruction’ of undertakings which have been running at a loss,

‘the share capital is written down, that is, profits are distributed on a smaller capital and subsequently are calculated on this smaller basis. If the income has fallen to zero, new capital is called in, which, combined with the old and less remunerative capital, will bring in an adequate return.’

‘Incidentally,’ adds Hilferding, ‘these reorganisations and reconstructions have a twofold significance for the banks: first, as profitable transactions; and secondly, as opportunities for securing control of the companies in difficulties.’

Here is an instance. The Union Mining Company of Dortmund, founded in 1872, with a share capital of nearly 40,000,000 marks, saw the market price of shares rise to 170 after it had paid a 12 per cent dividend in its first year. Finance capital skimmed the cream and earned a ‘trifle’ of something like 28,000,000 marks. The principal sponsor of this company was that very big German Disconto-Gesellschaft which so successfully attained a capital of 300,000,000 marks. Later, the dividends of the Union declined to nil: the shareholders had to consent to a ‘writing down’ of capital, that is, to losing some of it in order not to lose it all. By a series of ‘reconstructions,’ more than 73,000,000 marks were written off the books of the Union in the course of thirty years.

‘At the present time, the original shareholders of this company possess only 5 per cent of the nominal value of their shares.’

But the bank ‘made a profit’ out of every ‘reconstruction.’

Speculation in land situated in the suburbs of rapidly growing towns is a particularly profitable operation for finance capital. The monopoly of the banks merges here with the monopoly of ground rent and with monopoly in the means of communication, since the increase in the value of the land and the possibility of selling it profitably in allotments, etc., is mainly dependent on good means of communication with the centre of the town; and these means of communication are in the hands of large companies which are connected by means of the holding system, and by the distribution of positions on the directorates, with the interested banks. As a result we get what the German writer, L. Eschwege, a contributor to Die Bank, who has made a special study of real estate business and mortgages, etc., calls the formation of a ‘bog.’ Frantic speculation in suburban building lots: collapse of building enterprises (like that of the Berlin firm of Boswau and Knauer, which grabbed 100,000,000 marks with the help of the ‘sound and solid’ Deutsche Bank – the latter acting, of course, discreetly behind the scenes through the holding system and getting out of it by losing ‘only’ 12,000,000 marks), then the ruin of small proprietors and of workers who get nothing from the fraudulent building firms, underhand agreements with the ‘honest’ Berlin police and the Berlin administration for the purpose of getting control of the issue of building sites, tenders, building licences, etc.

‘American ethics,’ which the European professors and well-meaning bourgeois so hypocritically deplore, have, in the age of finance capital, become the ethics of literally every large city, no matter what country it is in.

At the beginning of 1914, there was talk in Berlin of the proposed formation of a ‘transport trust,’ i.e., of establishing ‘community of interests’ between the three Berlin passenger transport undertakings: the Metropolitan electric railway, the tramway company and the omnibus company.

‘We know,’ wrote Die Bank, ‘that this plan has been contemplated since it became known that the majority of the shares in the bus company has been acquired by the other two transport companies. … We may believe those who are pursuing this aim when they say that by uniting the transport services, they will secure economies part of which will in time benefit the public. But the question is complicated by the fact that behind the transport trust that is being formed are the banks, which, if they desire, can subordinate the means of transportation, which they have monopolised, to the interests of their real estate business. To be convinced of the reasonableness of such a conjecture, we need only recall that at the very formation of the Elevated Railway Company the traffic interests became interlocked with the real estate interests of the big bank which financed it, and this interlocking even created the prerequisites for the formation of the transport enterprise. Its eastern line, in fact, was to run through land which, when it became certain the line was to be laid down, this bank sold to a real estate firm at an enormous profit for itself and for several partners in the transactions.’

A monopoly, once it is formed and controls thousands of millions, inevitably penetrates into every sphere of public life, regardless of the form of government and all other ‘details.’ In the economic literature of Germany one usually comes across the servile praise of the integrity of the Prussian bureaucracy, and allusions to the French Panama scandal and to political corruption in America. But the fact is that even the bourgeois literature devoted to German banking matters constantly has to go far beyond the field of purely banking operations and to speak, for instance, of ‘the attraction of the banks’ in reference to the increasing frequency with which public officials take employment with the banks.

‘How about the integrity of a state official who in his inmost heart is aspiring to a soft job in the Behrenstrasse?’ (the street in Berlin in which the head office of the Deutsche Bank is situated).

In 1909, the publisher of Die Bank, Alfred Lansburgh, wrote an article entitled ‘The Economic Significance of Byzantinism,’ in which he incidentally referred to Wilhelm II’s tour of Palestine, and to ‘the immediate result of this journey,’ the construction of the Bagdad railway, that fatal ‘standard product of German enterprise, which is more responsible for the “encirclement” than all our political blunders put together.’ (By encirclement is meant the policy of Edward VII to isolate Germany by surrounding her with an imperialist anti-German alliance.) In 1912, another contributor to this magazine, Eschwege, to whom we have already referred, wrote an article entitled ‘Plutocracy and Bureaucracy,’ in which he exposes the case of a German official named Volker, who was a zealous member of the Cartel Committee and who, some time later, obtained a lucrative post in the biggest cartel, i.e., the Steel Syndicate. Similar cases, by no means casual, forced this bourgeois author to admit that ‘the economic liberty guaranteed by the German Constitution has become in many departments of economic life, a meaningless phrase’ and that under the existing rule of the plutocracy, ‘even the widest political liberty cannot save us from being converted into a nation of unfree people.’

As for Russia, we will content ourselves by quoting one example. Some years ago, all the newspapers announced that Davidov, the director of the Credit Department of the Treasury, had resigned his post to take employment with a certain big bank at a salary which, according to the contract, was to amount to over one million rubles in the course of several years. The function of the Credit Department is to ‘co-ordinate the activities of all the credit institutions of the country’; it also grants subsidies to banks in St. Petersburg and Moscow amounting to between 800 and 1,000 million rubles.

It is characteristic of capitalism in general that the ownership of capital is separated from the application of capital to production, that money capital is separated from industrial or productive capital, and that the rentier, who lives entirely on income obtained from money capital, is separated from the entrepreneur and from all who are directly concerned in the management of capital. Imperialism, or the domination of finance capital, is that highest stage of capitalism in which this separation reaches vast proportions. The supremacy of finance capital over all other forms of capital means the predominance of the rentier and of the financial oligarchy; it means the crystallisation of a small number of financially ‘powerful’ states from among all the rest. The extent to which this process is going on may be judged from the statistics on emissions, i.e., the issue of all kinds of securities.

In the Bulletin of the International Statistical Institute, A. Neymarck has published very comprehensive and complete comparative figures covering the issue of securities all over the world, which have been repeatedly quoted in economic literature. The following are the totals he gives for four decades:

| 1871–1880 | 76.1 |

| 1881–1890 | 64.5 |

| 1891–1900 | 100.4 |

| 1901–1910 | 197.8 |

In the 1870s, the total amount of issues for the whole world was high, owing particularly to the loans floated in connection with the Franco-Prussian War, and the company-promoting boom which set in in Germany after the war. In general, the increase is not very rapid during the three last decades of the nineteenth century, and only in the first ten years of the twentieth century is an enormous increase observed of almost 100 per cent. Thus the beginning of the twentieth century marks the turning point, not only in regard to the growth of monopolies (cartels, syndicates, trusts), of which we have already spoken, but also in regard to the development of finance capital.

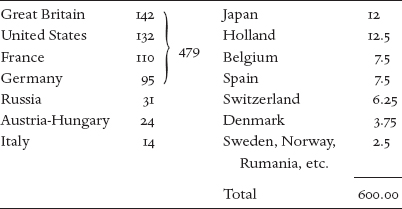

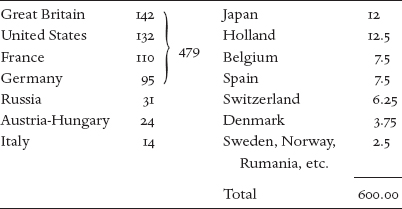

Neymarck estimates the total amount of issued securities current in the world in 1910 at about 815,000,000,000 francs. Deducting from this amounts which might have been duplicated, he reduces the total to 575–600,000,000,000, which is distributed among the various countries as follows (we will take 600,000,000,000):

Financial Securities Current In 1910

(In billions of francs)

From these figures we at once see standing out in sharp relief four of the richest capitalist countries, each of which controls securities to amounts ranging from 100 to 150 billion francs. Two of these countries, England and France, are the oldest capitalist countries, and, as we shall see, possess the most colonies; the other two, the United States and Germany, are in the front rank as regards rapidity of development and the degree of extension of capitalist monopolies in industry. Together, these four countries own 479,000,000,000 francs, that is, nearly 80 per cent of the world’s finance capital. Thus, in one way or another, nearly the whole world is more or less the debtor to and tributary of these four international banker countries, the four ‘pillars’ of world finance capital.

It is particularly important to examine the part which export of capital plays in creating the international network of dependence and ties of finance capital.