Monopolist capitalist combines – cartels, syndicates, trusts – divide among themselves, first of all, the whole internal market of a country, and impose their control, more or less completely, upon the industry of that country. But under capitalism the home market is inevitably bound up with the foreign market. Capitalism long ago created a world market. As the export of capital increased, and as the foreign and colonial relations and the ‘spheres of influence’ of the big monopolist combines expanded, things ‘naturally’ gravitated towards an international agreement among these combines, and towards the formation of international cartels.

This is a new stage of world concentration of capital and production, incomparably higher than the preceding stages. Let us see how this super-monopoly develops.

The electrical industry is the most typical of the modern technical achievements of capitalism of the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries. This industry has developed most in the two most advanced of the new capitalist countries, the United States and Germany. In Germany, the crisis of 1900 gave a particularly strong impetus to its concentration. During the crisis, the banks, which by this time had become fairly well merged with industry, greatly accelerated and deepened the collapse of relatively small firms and their absorption by the large ones.

‘The banks,’ writes Jeidels, ‘in refusing a helping hand to the very companies which are in greatest need of capital bring on first a frenzied boom and then the hopeless failure of the companies which have not been attached to them closely long enough.’

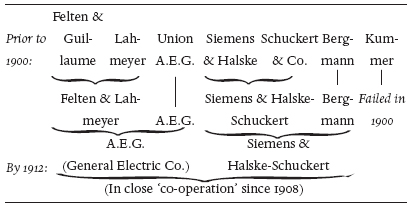

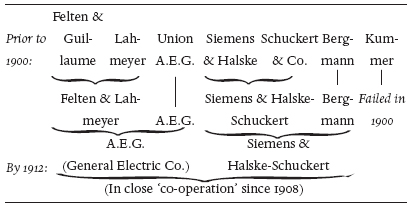

As a result, after 1900, concentration in Germany proceeded by leaps and bounds. Up to 1900 there had been seven or eight ‘groups’ in the electrical industry. Each was formed of several companies (altogether there were twenty-eight) and each was supported by from two to eleven banks. Between 1908 and 1912 all the groups were merged into two, or possibly one. The diagram below shows the process:

Groups in the German Electrical Industry

The famous A.E.G. (General Electric Company), which grew up in this way, controls 175 to 200 companies (through shareholdings), and a total capital of approximately 1,500,000,000 marks. Abroad, it has thirty-four direct agencies, of which twelve are joint stock companies, in more than ten countries. As early as 1904 the amount of capital invested abroad by the German electrical industry was estimated at 233,000,000 marks. Of this sum, 62,000,000 were invested in Russia. Needless to say, the A.E.G. is a huge combine. Its manufacturing companies alone number no less than sixteen, and their factories make the most varied articles, from cables and insulators to motor cars and aeroplanes.

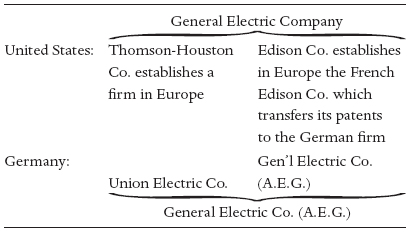

But concentration in Europe was a part of the process of concentration in America, which developed in the following way:

Thus, two ‘Great Powers’ in the electrical industry were formed. ‘There are no other electric companies in the world completely independent of them,’ wrote Heinig in his article ‘The Path of the Electric Trust.’ An idea, although far from complete, of the turnover and the size of the enterprises of the two ‘trusts’ can be obtained from the following figures:

| Turnover (mill. marks) | No. of employees | Net profits (mill. marks) | ||

| America: | ||||

| General Electric Co. |

1907 | 252 | 28,000 | 35.4 |

| 1910 | 298 | 32,000 | 45.6 | |

| Germany: A.E.G. | 1907 | 216 | 30,700 | 14.5 |

| 1911 | 362 | 60,800 | 21.7 |

In 1907, the German and American trusts concluded an agreement by which they divided the world between themselves. Competition between them ceased. The American General Electric Company ‘got’ the United States and Canada. The A.E.G. ‘got’ Germany, Austria, Russia, Holland, Denmark, Switzerland, Turkey and the Balkans. Special agreements, naturally secret, were concluded regarding the penetration of ‘subsidiary’ companies into new branches of industry, into ‘new’ countries formally not yet allotted. The two trusts were to exchange inventions and experiments.

It is easy to understand how difficult competition has become against this trust, which is practically world-wide, which controls a capital of several billion, and has its ‘branches,’ agencies, representatives, connections, etc., in every corner of the world. But the division of the world between two powerful trusts does not remove the possibility of redivision, if the relation of forces changes as a result of uneven development, war, bankruptcy, etc.

The oil industry provides an instructive example of attempts at such a redivision, or rather of a struggle for redivision.

‘The world oil market,’ wrote Jeidels in 1905, ‘is even today divided in the main between two great financial groups – Rockefeller’s American Standard Oil Co., and the controlling interests of the Russian oil-fields in Baku, Rothschild and Nobel. The two groups are in close alliance. But for several years, five enemies have been threatening their monopoly:’

1) The exhaustion of the American oil wells; 2) the competition of the firm of Mantashev of Baku; 3) the Austrian wells; 4) the Rumanian wells; 5) the overseas oilfields, particularly in the Dutch colonies (the extremely rich firms, Samuel and Shell, also connected with British capital). The three last groups are connected with the great German banks, principally, the Deutsche Bank. These banks independently and systematically developed the oil industry in Rumania, in order to have a foothold of their ‘own.’ In 1907, 185,000,000 francs of foreign capital were invested in the Rumanian oil industry, of which 74,000,000 came from Germany.

A struggle began, which in economic literature is fittingly called ‘the struggle for the division of the world.’ On one side, the Rockefeller trust, wishing to conquer everything, formed a subsidiary company right in Holland, and bought up oil wells in the Dutch Indies, in order to strike at its principal enemy, the Anglo-Dutch Shell trust. On the other side, the Deutsche Bank and the other German banks aimed at ‘retaining’ Rumania ‘for themselves’ and at uniting it with Russia against Rockefeller. The latter controlled far more capital and an excellent system of oil transport and distribution. The struggle had to end, and did end in 1907, with the utter defeat of the Deutsche Bank, which was confronted with the alternative: either to liquidate its oil business and lose millions, or to submit. It chose to submit, and concluded a very disadvantageous agreement with the American trust. The Deutsche Bank agreed ‘not to attempt anything which might injure American interests.’ Provision was made, however, for the annulment of the agreement in the event of Germany establishing a state oil monopoly.

Then the ‘comedy of oil’ began. One of the German finance kings, von Gwinner, a director of the Deutsche Bank, began through his private secretary, Strauss, a campaign for a state oil monopoly. The gigantic machine of the big German bank and all its wide ‘connections’ were set in motion. The press bubbled over with ‘patriotic’ indignation against the ‘yoke’ of the American trust, and, on March 15, 1911, the Reichstag by an almost unanimous vote, adopted a motion asking the government to introduce a bill for the establishment of an oil monopoly. The government seized upon this ‘popular’ idea, and the game of the Deutsche Bank, which hoped to cheat its American partner and improve its business by a state monopoly, appeared to have been won. The German oil magnates saw visions of wonderful profits, which would not be less than those of the Russian sugar refiners. … But, firstly, the big German banks quarrelled among themselves over the division of the spoils. The Disconto-Gesellschaft exposed the covetous aims of the Deutsche Bank; secondly, the government took fright at the prospect of a struggle with Rockefeller; it was doubtful whether Germany could be sure of obtaining oil from other sources. (The Rumanian output was small.) Thirdly, just at that time the 1913 credits of a billion marks were voted for Germany’s war preparations. The project of the oil monopoly was postponed. The Rockefeller trust came out of the struggle, for the time being, victorious.

The Berlin review, Die Bank, said in this connection that Germany could only fight the oil trust by establishing an electricity monopoly and by converting water power into cheap electricity.

‘But,’ the author added, ‘the electricity monopoly will come when the producers need it, that is to say, on the eve of the next great crash in the electrical industry, and when the powerful, expensive electric stations which are now being put up at great cost everywhere by private electrical concerns, which obtain partial monopolies from the state, from towns, etc., can no longer work at a profit. Water power will then have to be used. But it will be impossible to convert it into cheap electricity at state expense; it will have to be handed over to a “private monopoly controlled by the state,” because of the immense compensation and damages that would have to be paid to private industry. … So it was with the nitrate monopoly, so it is with the oil monopoly; so it will be with the electric power monopoly. It is time for our state socialists, who allow themselves to be blinded by beautiful principles, to understand once and for all that in Germany monopolies have never pursued the aim, nor have they had the result, of benefiting the consumer, or of handing over to the state part of the entrepreneurs’ profits; they have served only to facilitate, at the expense of the state, the recovery of private industries which were on the verge of bankruptcy.’

Such are the valuable admissions which the German bourgeois economists are forced to make. We see plainly here how private monopolies and state monopolies are bound up together in the age of finance capital; how both are but separate links in the imperialist struggle between the big monopolists for the division of the world.

In mercantile shipping, the tremendous development of concentration has ended also in the division of the world. In Germany two powerful companies have raised themselves to first rank, the Hamburg-Amerika and the Norddeutscher Lloyd, each having a capital of 200,000,000 marks (in stocks and bonds) and possessing 185 to 189 million marks worth of shipping tonnage. On the other side, in America, on January 1, 1903, the Morgan trust, the International Mercantile Marine Co., was formed which united nine British and American steamship companies, and which controlled a capital of 120,000,000 dollars (480,000,000 marks). As early as 1903, the German giants and the Anglo-American trust concluded an agreement and divided the world in accordance with the division of profits. The German companies undertook not to compete in the Anglo-American traffic. The ports were carefully ‘allotted’ to each; a joint committee of control was set up, etc. This contract was concluded for twenty years, with the prudent provision for its annulment in the event of war.

Extremely instructive also is the story of the creation of the International Rail Cartel. The first attempt of the British, Belgian and German rail manufacturers to create such a cartel was made as early as 1884, at the time of a severe industrial depression. The manufacturers agreed not to compete with one another for the home markets of the countries involved, and they divided the foreign markets in the following quotas: Great Britain 66 per cent; Germany 27 per cent; Belgium 7 per cent. India was reserved entirely for Great Britain. Joint war was declared against a British firm which remained outside the cartel. The cost of this economic war was met by a percentage levy on all sales. But in 1886 the cartel collapsed when two British firms retired from it. It is characteristic that agreement could not be achieved in the period of industrial prosperity which followed.

At the beginning of 1904, the German steel syndicate was formed. In November 1904, the International Rail Cartel was revived, with the following quotas for foreign trade: England 53.5 per cent; Germany 28.83 per cent; Belgium 17.67 per cent. France came in later with 4.8 per cent, 5.8 per cent and 6.4 per cent in the first, second and third years respectively, in excess of the 100 per cent limit, i.e., when the total was 104.8 per cent, etc. In 1905, the United States Steel Corporation entered the cartel; then Austria; then Spain.

‘At the present time,’ wrote Vogelstein in 1910, ‘the division of the world is completed, and the big consumers, primarily the state railways – since the world has been parcelled out without consideration for their interests – can now dwell like the poet in the heaven of Jupiter.’

We will mention also the International Zinc Syndicate, established in 1909, which carefully apportioned output among five groups of factories: German, Belgian, French, Spanish and British. Then there is the International Dynamite Trust, of which Liefmann says that it is

‘quite a modern, close alliance of all the manufacturers of explosives who, with the French and American dynamite manufacturers who have organised in a similar manner, have divided the whole world among themselves, so to speak.’

Liefmann calculated that in 1897 there were altogether about forty international cartels in which Germany had a share, while in 1910 there were about a hundred.

Certain bourgeois writers (with whom K. Kautsky, who has completely abandoned the Marxist position he held, for example, in 1909, has now associated himself) express the opinion that international cartels are the most striking expressions of the internationalisation of capital, and, therefore, give the hope of peace among nations under capitalism. Theoretically, this opinion is absurd, while in practice it is sophistry and a dishonest defence of the worst opportunism. International cartels show to what point capitalist monopolies have developed, and they reveal the object of the struggle between the various capitalist groups. This last circumstance is the most important; it alone shows us the historico-economic significance of events; for the forms of the struggle may and do constantly change in accordance with varying, relatively particular, and temporary causes, but the essence of the struggle, its class content, cannot change while classes exist. It is easy to understand, for example, that it is in the interests of the German bourgeoisie, whose theoretical arguments have now been adopted by Kautsky (we will deal with this later), to obscure the content of the present economic struggle (the division of the world) and to emphasise this or that form of the struggle. Kautsky makes the same mistake. Of course, we have in mind not only the German bourgeoisie, but the bourgeoisie all over the world. The capitalists divide the world, not out of any particular malice, but because the degree of concentration which has been reached forces them to adopt this method in order to get profits. And they divide it in proportion to ‘capital,’ in proportion to ‘strength,’ because there cannot be any other system of division under commodity production and capitalism. But strength varies with the degree of economic and political development. In order to understand what takes place, it is necessary to know what questions are settled by this change of forces. The question as to whether these changes are ‘purely’ economic or non-economic (e.g., military) is a secondary one, which does not in the least affect the fundamental view on the latest epoch of capitalism. To substitute for the question of the content of the struggle and agreements between capitalist combines the question of the form of these struggles and agreements (today peaceful, tomorrow war-like, the next day war-like again) is to sink to the role of a sophist.

The epoch of modern capitalism shows us that certain relations are established between capitalist alliances, based on the economic division of the world; while parallel with this fact and in connection with it, certain relations are established between political alliances, between states, on the basis of the territorial division of the world, of the struggle for colonies, of the ‘struggle for economic territory.’