In his book, The Territorial Development of the European Colonies, A. Supan, the geographer, gives the following brief summary of this development at the end of the nineteenth century:

| 1876 | 1900 | Increase or Decrease | |

| Africa | 10.8 | 90.4 | +79.6 |

| Polynesia | 56.8 | 98.9 | +42.1 |

| Asia | 51.5 | 56.6 | +5.1 |

| Australia | 100.0 | 100.0 | — |

| America | 27.5 | 27.2 | −0.3 |

‘The characteristic feature of this period,’ he concludes, ‘is therefore, the division of Africa and Polynesia.’

As there are no unoccupied territories – that is, territories that do not belong to any state – in Asia and America, Mr. Supan’s conclusion must be carried further, and we must say that the characteristic feature of this period is the final partition of the globe – not in the sense that a new partition is impossible – on the contrary, new partitions are possible and inevitable – but in the sense that the colonial policy of the capitalist countries has completed the seizure of the unoccupied territories on our planet. For the first time the world is completely divided up, so that in the future only redivision is possible; territories can only pass from one ‘owner’ to another, instead of passing as unowned territory to an ‘owner.’

Hence, we are passing through a peculiar period of world colonial policy, which is closely associated with the ‘latest stage in the development of capitalism,’ with finance capital. For this reason, it is essential first of all to deal in detail with the facts, in order to ascertain exactly what distinguishes this period from those preceding it, and what the present situation is. In the first place, two questions of fact arise here. Is an intensification of colonial policy, an intensification of the struggle for colonies, observed precisely in this period of finance capital? And how, in this respect, is the world divided at the present time?

The American writer, Morris, in his book on the history of colonisation, has made an attempt to compile data on the colonial possessions of Great Britain, France and Germany during different periods of the nineteenth century. The following is a brief summary of the results he has obtained:

| Great Britain | France | ||||

| Area | Pop. | Area | Pop. | ||

| 1815–30 | ? | 126.4 | 0.02 | 0.5 | |

| 1860 | 2.5 | 145.1 | 0.2 | 3.4 | |

| 1880 | 7.7 | 267.9 | 0.7 | 7.5 | |

| 1899 | 9.3 | 309.0 | 3.7 | 56.4 | |

| Germany | ||

| Area | Pop. | |

| 1815–30 | — | — |

| 1860 | — | — |

| 1880 | — | — |

| 1899 | 1.0 | 14.7 |

For Great Britain, the period of the enormous expansion of colonial conquests is that between 1860 and 1880, and it was also very considerable in the last twenty years of the nineteenth century. For France and Germany this period falls precisely in these last twenty years. We saw above that the apex of pre-monopoly capitalist development, of capitalism in which free competition was predominant, was reached in the ’sixties and ’seventies of the last century. We now see that it is precisely after that period that the ‘boom’ in colonial annexations begins, and that the struggle for the territorial division of the world becomes extraordinarily keen. It is beyond doubt, therefore, that capitalism’s transition to the stage of monopoly capitalism, to finance capital, is bound up with the intensification of the struggle for the partition of the world.

Hobson, in his work on imperialism, marks the years 1884–1900 as the period of the intensification of the colonial ‘expansion’ of the chief European states. According to his estimate, Great Britain during these years acquired 3,700,000 square miles of territory with a population of 57,000,000; France acquired 3,600,000 square miles with a population of 36,500,000; Germany 1,000,000 square miles with a population of 16,700,000; Belgium 900,000 square miles with 30,000,000 inhabitants; Portugal 800,000 square miles with 9,000,000 inhabitants. The quest for colonies by all the capitalist states at the end of the nineteenth century and particularly since the 1880s is a commonly known fact in the history of diplomacy and of foreign affairs.

When free competition in Great Britain was at its zenith, i.e., between 1840 and 1860, the leading British bourgeois politicians were opposed to colonial policy and were of the opinion that the liberation of the colonies and their complete separation from Britain was inevitable and desirable. M. Beer, in an article, ‘Modern British Imperialism,’ published in 1898, shows that in 1852, Disraeli, a statesman generally inclined towards imperialism, declared: ‘The colonies are millstones round our necks.’ But at the end of the nineteenth century the heroes of the hour in England were Cecil Rhodes and Joseph Chamberlain, open advocates of imperialism, who applied the imperialist policy in the most cynical manner.

It is not without interest to observe that even at that time these leading British bourgeois politicians fully appreciated the connection between what might be called the purely economic and the politico-social roots of modern imperialism. Chamberlain advocated imperialism by calling it a ‘true, wise and economical policy,’ and he pointed particularly to the German, American and Belgian competition which Great Britain was encountering in the world market. Salvation lies in monopolies, said the capitalists as they formed cartels, syndicates and trusts. Salvation lies in monopolies, echoed the political leaders of the bourgeoisie, hastening to appropriate the parts of the world not yet shared out. The journalist, Stead, relates the following remarks uttered by his close friend Cecil Rhodes, in 1895, regarding his imperialist ideas:

‘I was in the East End of London yesterday and attended a meeting of the unemployed. I listened to the wild speeches, which were just a cry for “bread,” “bread,” “bread,” and on my way home I pondered over the scene and I became more than ever convinced of the importance of imperialism. … My cherished idea is a solution for the social problem, i.e., in order to save the 40,000,000 inhabitants of the United Kingdom from a bloody civil war, we colonial statesmen must acquire new lands to settle the surplus population, to provide new markets for the goods produced by them in the factories and mines. The Empire, as I have always said, is a bread and butter question. If you want to avoid civil war, you must become imperialists.’

This is what Cecil Rhodes, millionaire, king of finance, the man who was mainly responsible for the Boer War, said in 1895. His defence of imperialism is just crude and cynical, but in substance it does not differ from the ‘theory’ advocated by Messrs. Maslov, Südekum, Potresov, David, and the founder of Russian Marxism and others. Cecil Rhodes was a somewhat more honest social-chauvinist.

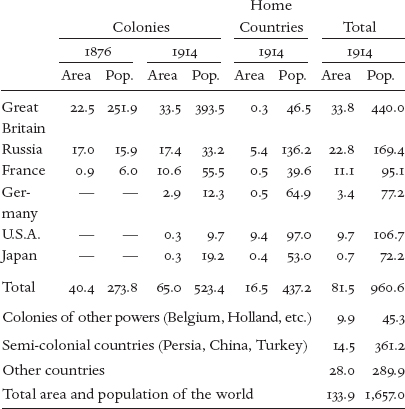

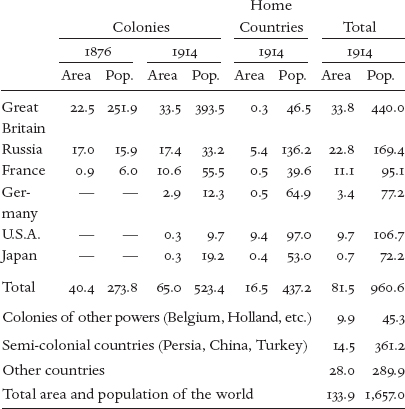

To tabulate as exactly as possible the territorial division of the world, and the changes which have occurred during the last decades, we will take the data furnished by Supan in the work already quoted on the colonial possessions of all the powers of the world. Supan examines the years 1876 and 1900; we will take the year 1876 – a year aptly selected, for it is precisely at that time that the pre-monopolist stage of development of West European capitalism can be said to have been completed, in the main, and we will take the year 1914, and in place of Supan’s figures we will quote the more recent statistics of Hübner’s Geographical and Statistical Tables. Supan gives figures only for colonies: we think it useful in order to present a complete picture of the division of the world to add brief figures on non-colonial and semi-colonial countries like Persia, China and Turkey. Persia is already almost completely a colony; China and Turkey are on the way to becoming colonies. We thus get the following summary:

Colonial Possessions of the Great Powers

(Million square kilometres and million inhabitants)

We see from these figures how ‘complete’ was the partition of the world at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries. After 1876 colonial possessions increased to an enormous degree, more than one and a half times, from 40,000,000 to 65,000,000 square kilometres in area for the six biggest powers, an increase of 25,000,000 square kilometres, that is, one and a half times greater than the area of the ‘home’ countries, which have a total of 16,500,000 square kilometres. In 1876 three powers had no colonies, and a fourth, France, had scarcely any. In 1914 these four powers had 14,100,000 square kilometres of colonies, or an area one and a half times greater than that of Europe, with a population of nearly 100,000,000. The unevenness in the rate of expansion of colonial possessions is very marked. If, for instance, we compare France, Germany and Japan, which do not differ very much in area and population, we will see that the first has annexed almost three times as much colonial territory as the other two combined. In regard to finance capital, also, France, at the beginning of the period we are considering, was perhaps several times richer than Germany and Japan put together. In addition to, and on the basis of, purely economic causes, geographical conditions and other factors also affect the dimensions of colonial possessions. However strong the process of levelling the world, of levelling the economic and living conditions in different countries, may have been in the past decades as a result of the pressure of large-scale industry, exchange and finance capital, great differences still remain; and among the six powers, we see, firstly, young capitalist powers (America, Germany, Japan) which progressed very rapidly; secondly, countries with an old capitalist development (France and Great Britain), which, of late, have made much slower progress than the previously mentioned countries, and, thirdly, a country (Russia) which is economically most backward, in which modern capitalist imperialism is enmeshed, so to speak, in a particularly close network of pre-capitalist relations.

Alongside the colonial possessions of these great powers, we have placed the small colonies of the small states, which are, so to speak, the next possible and probable objects of a new colonial ‘share-out.’ Most of these little states are able to retain their colonies only because of the conflicting interests, frictions, etc., among the big powers, which prevent them from coming to an agreement in regard to the division of the spoils. The ‘semi-colonial states’ provide an example of the transitional forms which are to be found in all spheres of nature and society. Finance capital is such a great, it may be said, such a decisive force in all economic and international relations, that it is capable of subordinating to itself, and actually does subordinate to itself, even states enjoying complete political independence. We shall shortly see examples of this. Naturally, however, finance capital finds it most ‘convenient,’ and is able to extract the greatest profit from a subordination which involves the loss of the political independence of the subjected countries and peoples. In this connection, the semi-colonial countries provide a typical example of the ‘middle stage.’ It is natural that the struggle for these semi-dependent countries should have become particularly bitter during the period of finance capital, when the rest of the world had already been divided up.

Colonial policy and imperialism existed before this latest stage of capitalism, and even before capitalism. Rome, founded on slavery, pursued a colonial policy and achieved imperialism. But ‘general’ arguments about imperialism, which ignore, or put into the background the fundamental difference of social-economic systems, inevitably degenerate into absolutely empty banalities, or into grandiloquent comparisons like ‘Greater Rome and Greater Britain.’ Even the colonial policy of capitalism in its previous stages is essentially different from the colonial policy of finance capital.

The principal feature of modern capitalism is the domination of monopolist combines of the big capitalists. These monopolies are most firmly established when all the sources of raw materials are controlled by the one group. And we have seen with what zeal the international capitalist combines exert every effort to make it impossible for their rivals to compete with them; for example, by buying up mineral lands, oil fields, etc. Colonial possession alone gives complete guarantee of success to the monopolies against all the risks of the struggle with competitors, including the risk that the latter will defend themselves by means of a law establishing a state monopoly. The more capitalism is developed, the more the need for raw materials is felt, the more bitter competition becomes, and the more feverishly the hunt for raw materials proceeds throughout the whole world, the more desperate becomes the struggle for the acquisition of colonies.

Schilder writes:

‘It may even be asserted, although it may sound paradoxical to some, that in the more or less discernible future the growth of the urban industrial population is more likely to be hindered by a shortage of raw materials for industry than by a shortage of food.’

For example, there is a growing shortage of timber – the price of which is steadily rising – of leather, and raw materials for the textile industry.

‘As instances of the efforts of associations of manufacturers to create an equilibrium between industry and agriculture in world economy as a whole, we might mention the International Federation of Cotton Spinners’ Associations in the most important industrial countries, founded in 1904, and the European Federation of Flax Spinners’ Associations, founded on the same model in 1910.’

The bourgeois reformists, and among them particularly the present-day adherents of Kautsky, of course, try to belittle the importance of facts of this kind by arguing that it ‘would be possible’ to obtain raw materials in the open market without a ‘costly and dangerous’ colonial policy; and that it would be ‘possible’ to increase the supply of raw materials to an enormous extent ‘simply’ by improving agriculture. But these arguments are merely an apology for imperialism, an attempt to embellish it, because they ignore the principal feature of modern capitalism: monopoly. Free markets are becoming more and more a thing of the past; monopolist syndicates and trusts are restricting them more and more every day, and ‘simply’ improving agriculture reduces itself to improving the conditions of the masses, to raising wages and reducing profits. Where, except in the imagination of the sentimental reformists, are there any trusts capable of interesting themselves in the condition of the masses instead of the conquest of colonies?

Finance capital is not only interested in the already known sources of raw materials; it is also interested in potential sources of raw materials, because present-day technical development is extremely rapid, and because land which is useless today may be made fertile tomorrow if new methods are applied (to devise these new methods a big bank can equip a whole expedition of engineers, agricultural experts, etc.), and large amounts of capital are invested. This also applies to prospecting for minerals, to new methods of working up and utilising raw materials, etc., etc. Hence, the inevitable striving of finance capital to extend its economic territory and even its territory in general. In the same way that the trusts capitalise their property by estimating it at two or three times its value, taking into account its ‘potential’ (and not present) returns, and the further results of monopoly, so finance capital strives to seize the largest possible amount of land of all kinds and in any place it can, and by any means, counting on the possibilities of finding raw materials there, and fearing to be left behind in the insensate struggle for the last available scraps of undivided territory, or for the repartition of that which has been already divided.

The British capitalists are exerting every effort to develop cotton growing in their colony, Egypt (in 1904, out of 2,300,000 hectares of land under cultivation, 600,000, or more than one-fourth, were devoted to cotton growing); the Russians are doing the same in their colony, Turkestan; and they are doing so because in this way they will be in a better position to defeat their foreign competitors, to monopolise the sources of raw materials and form a more economical and profitable textile trust in which all the processes of cotton production and manufacturing will be ‘combined’ and concentrated in the hands of a single owner.

The necessity of exporting capital also gives an impetus to the conquest of colonies, for in the colonial market it is easier to eliminate competition, to make sure of orders, to strengthen the necessary ‘connections,’ etc., by monopolist methods (and sometimes it is the only possible way).

The non-economic superstructure which grows up on the basis of finance capital, its politics and its ideology, stimulates the striving for colonial conquest. ‘Finance capital does not want liberty, it wants domination,’ as Hilferding very truly says. And a French bourgeois writer, developing and supplementing, as it were, the ideas of Cecil Rhodes, which we quoted above, writes that social causes should be added to the economic causes of modern colonial policy.

‘Owing to the growing difficulties of life which weigh not only on the masses of the workers, but also on the middle classes, impatience, irritation and hatred are accumulating in all the countries of the old civilisation and are becoming a menace to public order; employment must be found for the energy which is being hurled out of the definite class channel; it must be given an outlet abroad in order to avert an explosion at home.’

Since we are speaking of colonial policy in the period of capitalist imperialism, it must be observed that finance capital and its corresponding foreign policy, which reduces itself to the struggle of the Great Powers for the economic and political division of the world, give rise to a number of transitional forms of national dependence. The division of the world into two main groups – of colony-owning countries on the one hand and colonies on the other – is not the only typical feature of this period; there is also a variety of forms of dependent countries; countries which, officially, are politically independent, but which are, in fact, enmeshed in the net of financial and diplomatic dependence. We have already referred to one form of dependence – the semi-colony. Another example is provided by Argentina.

‘South America, and especially Argentina,’ writes Schulze-Gaevernitz in his work on British imperialism, ‘is so dependent financially on London that it ought to be described as almost a British commercial colony.’

Basing himself on the report of the Austro-Hungarian consul at Buenos Aires for 1909, Schilder estimates the amount of British capital invested in Argentina at 8,750,000,000 francs. It is not difficult to imagine the solid bonds that are thus created between British finance capital (and its faithful ‘friend,’ diplomacy) and the Argentine bourgeoisie, with the leading businessmen and politicians of that country.

A somewhat different form of financial and diplomatic dependence, accompanied by political independence, is presented by Portugal. Portugal is an independent sovereign state. In actual fact, however, for more than two hundred years, since the war of the Spanish Succession (1700–14), it has been a British protectorate. Great Britain has protected Portugal and her colonies in order to fortify her own positions in the fight against her rivals, Spain and France. In return she has received commercial advantages, preferential import of goods, and, above all, of capital into Portugal and the Portuguese colonies, the right to use the ports and islands of Portugal, her telegraph cables, etc. Relations of this kind have always existed between big and little states. But during the period of capitalist imperialism they become a general system, they form part of the process of ‘dividing the world’; they become a link in the chain of operations of world finance capital.

In order to complete our examination of the question of the division of the world, we must make the following observation. This question was raised quite openly and definitely not only in American literature after the Spanish-American War, and in English literature after the Boer War, at the very end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth; not only has German literature, which always ‘jealously’ watches ‘British imperialism,’ systematically given its appraisal of this fact, but it has also been raised in French bourgeois literature in terms as wide and clear as they can be made from the bourgeois point of view. We will quote Driault, the historian, who, in his book, Political and Social Problems at the End of the Nineteenth Century, in the chapter ‘The Great Powers and the Division of the World,’ wrote the following:

‘During recent years, all the free territory of the globe, with the exception of China, has been occupied by the powers of Europe and North America. Several conflicts and displacements of influence have already occurred over this matter, which foreshadow more terrible outbreaks in the near future. For it is necessary to make haste. The nations which have not yet made provisions for themselves run the risk of never receiving their share and never participating in the tremendous exploitation of the globe which will be one of the essential features of the next century’ (i.e., the twentieth). ‘That is why all Europe and America has lately been afflicted with the fever of colonial expansion, of “imperialism,” that most characteristic feature of the end of the nineteenth century.’

And the author added:

‘In this partition of the world, in this furious pursuit of the treasures and of the big markets of the globe, the relative power of the empires founded in this nineteenth century is totally out of proportion to the place occupied in Europe by the nations which founded them. The dominant powers in Europe, those which decide the destinies of the Continent, are not equally preponderant in the whole world. And, as colonial power, the hope of controlling hitherto unknown wealth, will obviously react to influence the relative strength of the European powers, the colonial question – “imperialism,” if you will – which has already modified the political conditions of Europe, will modify them more and more.’