— CHAPTER 1 —

TENDER YEARS

Few people remember much of their lives before the age of five, but I certainly remember my fifth year clearly, since I nearly died. I got very sick: I had a fever and couldn’t keep anything in my stomach. An intense pain developed in my abdomen, but my mother, the youngest in her own big family, had little experience with sick children. Busy hosting a family party that night at our home she simply had me curl up in bed, not realizing I had a ruptured appendix. There I was until about midnight when my grandfather decided to check in on me.

“My God!” he cried, “she’s burning up!” My mother began to cry as she saw how sick I was. Grandpa scooped me up in his arms, hurried to his car and drove to us to the nearest hospital. It was cold outside, and he had my mother hold my head out the window to cool me down. The doctors later said that may have saved my life, but just barely. I was operated on immediately, but the situation was dire. My appendix had ruptured, and gangrene had spread everywhere. Massive amounts of penicillin and steroids were pumped into my body, along with blood transfusions. My family prayed. Father Rose, our family priest, came to administer Extreme Unction — the last rites.

They rolled me out of the operating room for the rites, then rolled me back in. Somehow, I made it through the night on the operating table, but there would be many more operations to come. Surgery after surgery, where they cut away infected tissues and even portions of my intestines. Peritonitis, gangrene, abscesses, bowel obstruction ... a hole developed in my stomach that allowed acids to leak into the upper portion of my torso. Unable to eat, I was fed by tubes snaked down my throat. Tubes were also in my arms, to add fluids, while tubes in my belly and abdomen drained fluids away. There is no describing the pain and helplessness I felt. I would gaze at a picture of the Virgin Mary hanging on the wall and try to deal with it. The nuns of Notre Dame had brought the picture in, and learning that I begged for Holy Communion, though I was only five, priests came and celebrated Communion with me for months. It was there that I learned to pray.

Most of the time, I was totally dependent upon the care of the nursing staff for my daily needs. Catholic nuns sat at my bedside and prayed aloud. They called me their “Little Angel” and asked God to keep me alive. I needed so many transfusions that the hospital ran out of my blood type. My family was so desperate they recruited my Uncle Leo, who was considered the black sheep of the family because he had swindled half a million dollars from his own mother. But he had Type O blood in his veins, and I needed it in mine. My situation was so urgent that the transfusion was done directly, arm-to-arm. I guess one could say that Uncle Leo saved my life but, ironically, I never saw him again.

By the time the ordeal was over, I had spent a year and a half in the Pawating Hospital on St. Joseph’s Avenue in Niles, Michigan. It was a dreadful experience for a young child. I remember thinking it would never end. But God delivered me from it, or so I was told.

I had missed nearly two years of school. My abdomen was scarred inside and out. I lived with abdominal pain so intense they finally operated on me again when I was ten to remove the adhesions caused by the earlier surgeries. Complications from the experience, such as extreme nearsightedness and a chronic problem with swallowing, have plagued me for the rest of my life. Eventually, I was told that due to all of the infections, abdominal surgeries and scarring, the doctors did not think I would ever be able to have children.

This was my introduction to the worlds of medicine and prayer. Needless to say, it was the major formative event of my early years, and it made me extremely close to my mother’s large, affectionate Hungarian family, who visited me constantly during my long recovery, particularly my mother’s older half-sister, Aunt Elsie. And the support of the nuns, who continued to educate me throughout my elementary school years, made me very religious. The long recovery also gave me lots of time to read and to draw.

I was born in Epworth Hospital in South Bend, Indiana on May 15, 1943, during the height of World War II. The hospital was so crowded with wounded soldiers that I was born in its corridor. My mother was very young — only 17 — but she’d already been married to my father for two years. My parents had eloped after my 15-year-old mother was forbidden to see 21-year-old Donald Vary anymore. But they were headstrong, and deeply in love.

My mother’s big Hungarian family insisted that my father join the Catholic Church if he ever expected forgiveness. So he did, and a Catholic wedding was held at a side altar. Only then did my grandparents recognize their daughter’s marriage. My mother owned five acres of land in Bertrand, Michigan, where my father and his father George, who was a boatwright and carpenter, built her a lovely home. That house was beautiful, but it was wartime, and pipes for plumbing were impossible to find. Fifteen months after I was born, one more child joined the family: my sister, Lynda.

My father was a successful electrical engineer, and had invented some of the electronic parts used in the television sets of the day.1 He also owned stores that sold and repaired television sets and was part-owner of a local TV station where he worked as the managing engineer. We were not rich by any definition of the term, but my father had a good income and a bright future. We were “comfortable” economically.

The Redstone Rocket Program

The Redstone rocket was the first U. S. ballistic missile to carry a nuclear warhead.

It had a range of 500 miles. Chrysler produced over 100 of these missiles, which were deployed in Germany between 1958 and 1964.

Problems with the guidance system led Chrysler to recruit new electrical engineers, like Judyth’s father Donald Vary, from outside their organization. This highly classified work was to be done at the U.S. Government’s Sandia National Laboratory on the grounds of Kirkland Air Force Base in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

When I was eleven, my father started doing engineering consulting at the Chrysler plant in Warren, Michigan, where Chrysler produced the Redstone missile.2 As a result of this consulting work, he was offered a remarkable job at Sandia National Laboratory, a U.S. Government research facility in New Mexico. Sandia handled the engineering work for the better-known Los Alamos National Laboratory, home of the atomic bomb. The government planned to adapt the atomic bomb to use in rockets, and wanted to make sure no electrical problems would exist regarding the guidance system and its deadly payload.

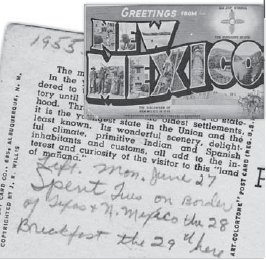

This postcard, recently discovered by Donald Vary’s granddaughter, establishes the date of his visit to New Mexico as June 29, 1955. Redstone’s new guidance system was tested three months later, on September 22, 1955, at White Sands.

It missed its target by 74 miles, proving the guidance system still needed considerable improvement.

Donald Vary declined the assignment in New Mexico and moved to St. Petersburg, Florida in 1955.

It was a prestigious Cold War assignment, and my father eagerly accepted the offer. He had deep patriotic motives, as well. He’d injured his leg in a motorcycle accident and was classified 4-F (unsuitable for military service) — the only male in the whole family who hadn’t served in any war — and my father felt it keenly. Having passed a lengthy security investigation, and with the imminent sales of his interest in the television station, our TV store and our home, in June 1955, my father drove us to the Sandia National Laboratories compound outside Albuquerque, New Mexico, two weeks before making the final leap. After all, we would be leaving our big extended family behind.

There, my father encountered a problem he had not anticipated: barbed-wire fences. Scientists working on important national security projects, like missile guidance systems, were required to live on the grounds of the Air Force base which housed the laboratories. The base was surrounded by high chain-link fences topped with barbed-wire and protected by armed guards at the gates. My mother took one look at the fences and informed my father that she was not going to raise their children in a prison surrounded by barbed wire. It was an ultimatum made by a strong-willed woman who loved freedom. My father was forced to choose between his dream career and his family. He chose family. But it was a high price for him to pay, and the decision haunted him for the rest of his life.

Thanks to the sale of the TV station, the stores and the royalties he earned from his inventions, he had enough money to move us to St. Petersburg, near Tampa on the west coast of Florida. There we lived near other members of my mother’s family, who followed us to the same area. It is in Florida that this story really begins.

“St. Pete”, as it is commonly called, is on the north side of Tampa Bay. Its beaches are some of the most beautiful in America. The innocence of our life seems, in retrospect, like an idealized vision of suburban America in the 1950s. Ozzie & Harriet, Leave it to Beaver, and Father Knows Best played on the television sets my father had helped design. We were patriotic, middle-class and Catholic. America was at peace for the most part and the Cold War seemed far, far away.3

The fight against cancer, however, was much closer to home, at least for me. My beloved grandmother (my mother’s mother, who lived near us) was dying from breast cancer. I visited her three times each week on my way home from school. I loved her dearly, and affectionately called her by her Hungarian nickname “Nanitsa.” Watching her die was terribly painful, but not without purpose. It instilled within me a deep hatred of cancer. Being helpless to stop the insidious growth inside her was extremely frustrating to me. It was 1957.

Later that same year, our family moved once more, to nearby Bradenton, a smaller town on the south side of Tampa Bay. Bradenton is located on the banks of the Manatee River, a wide, peaceful waterway which flows into the Gulf of Mexico.

Once in Bradenton, I was enrolled in Walker Jr. High School, a public school whose campus adjoined Manatee High School.4 Now in 8th grade, I had an art class, and my teacher gave us the assignment of painting a landscape. I set my easel up at the bridge that crossed the Manatee River near the hospital and began painting the river and the beautiful homes nestled along its banks.5

Before long, a woman came walking by and stopped to look at my painting. Slender, well-dressed, and older than my mother, she studied my work for a moment, then asked me politely where I had learned to paint. I told her I had been painting for many years and that my uncle, who was an artist, had bought me my first set of oil paints to get me started. When I told her that I was currently studying art at Walker Jr. High, she said she knew my art teacher, Mrs. DePew. As I would soon learn, this woman knew almost all of my teachers, and practically everyone else of significance in Bradenton. When she explained that she ran the local chapter of the American Cancer Society, I told her about my grandmother’s cancer, and that I, too, wanted to help in the fight against cancer. She inquired as to my name and then introduced herself as Mrs. Georgianna Watkins. Then she politely excused herself and headed to a garden party at a nearby church.

Several days later, Mrs. Watkins contacted my art teacher at school and asked if I would be willing to paint posters for her American Cancer Society meetings. As it turned out, Mrs. Watkins lived in our neighborhood, just a few blocks away.6 So, with my mother’s permission, I began going to her house to help with her American Cancer Society work.

Mrs. Watkins was a widow who lived alone. Her home was basically devoted to her cancer society work. The front room was full of books and literature about cancer. Other rooms stored assorted medical supplies and various cancer society materials. At first, I simply helped her cut and fold bandages which she delivered to patients at the local hospital. Mrs. Watkins obviously had some kind of medical training (I think she had been a nurse), and I admired the way she spoke knowledgeably about medicine. She taught me my first medical lingo, and I spent my spare time at her house reading about cancer. Mrs. Watkins apparently enjoyed my company and became a mentor to me. She came to play an important role in my life for the next several years.

Back at home, my constant playmate was my sister Lynda. We did the things that teenage girls typically did back then. There was school, church, choir, Girl Scouts, sock hops, slumber parties, and, of course, we had boyfriends who took us roller-skating, to movies, horseback riding and water-skiing.

Both my parents were quite musical. Our father was a good pianist and entertained family and friends with his wide repertoire from jazz to Hungarian czardas. Our mother had a beautiful singing voice, and was well versed in the pop music of her day. They made sure we had piano lessons at an early age and later voice lessons.7 We both sang in the glee club at school and in our church choir at St. Mary’s.

At home, Lynda and I sang constantly, especially with our mother who was quite good at harmony. We practiced various duets and performed them on local television shows.8 Our first such song was “The Cat Came Back.” Later we sang “Tonight You Belong To Me” at a talent show in St. Petersburg and won a prize. I also sang solos in a number of programs.9

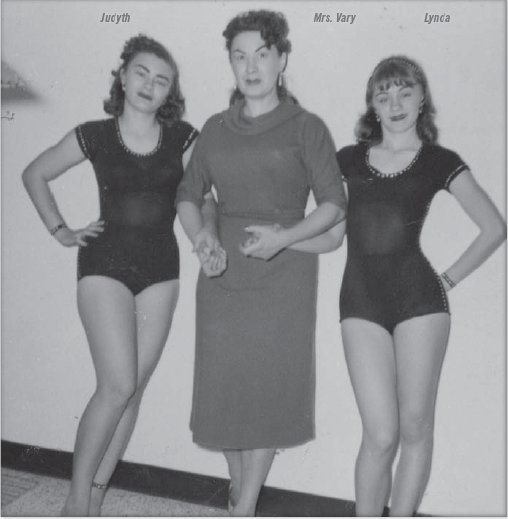

One year Lynda and I went to circus school. Bordering Bradenton to the south is Sarasota, the winter home of the Ringling Brothers Circus, and the location of the Ringling Museum. There is a school in Sarasota (today called the Sailor Circus) that trains school children in the performing arts, such as acrobatics, juggling, clowning, high-wire and trapeze, as well as backstage theatrical arts such as costume, lighting, make-up, and stage management. It started with a single gymnastics class in 1949, but today is a permanent 4-ring circus that bills itself as The Greatest “Little” Show On Earth.10 Lynda and I enrolled in their summer program to study gymnastics and acrobatics, and we put together an act, which we performed around town at places like retirement homes.

Lynda and I studied hypnosis and hypnotized each other to improve our concentration and block out distractions. This, combined with my ability to block out pain acquired during my long hospital stay as a child, gave me an extraordinary ability to concentrate, which might help explain why I became such a fast reader. At one point my reading speed was reported to be 3,400 words-per-minute.

In high school, Lynda won baton trophies and became a majorette — a bubbly portrait of wholesome normalcy.11, But I was being seduced by science, by great authors and poetry: I threw myself into books. Though Lynda and I continued our acrobatic act, a deep hunger to learn consumed me. I began reading the high school’s Encyclopedia Britannica on a daily basis in the 9th grade. By the 10th grade I had completed all 24 volumes of the 1956 edition.

Bradenton looked like many other small Southern towns of that era, with a brick courthouse, a Rexall Drug Store, and a Woolworth’s Department Store. I sometimes went shopping with my friends after school, and one day, after buying some Elvis records, we discovered that Woolworth’s had some mollies (small black tropical fish) on sale. I noticed one molly had a rather large belly. The salesperson told us she was pregnant, and that this small fish was viviparous; she bore her young alive, instead of laying eggs. My parents had a big tank full of angelfish and other exotics, but none of them bore their young alive. Intrigued, I returned the Elvis records and purchased half a dozen mollies and a small tank.

Several days later, the pregnant molly (I named her “Miss Molly”) gave birth. Her babies popped out one by one, but something was wrong. She still had a big lump, and I worried that she was retaining some unborn babies. But our veterinarian, who took care of my mother’s poodles, was also an expert on fish and told me she probably had cancer. Nevertheless, Miss Molly was soon pregnant again, but as her time to deliver drew near, she struggled to swim, and gasped for breath. It was clear that she was dying.

As Miss Molly slowly sank to the bottom of the tank, all I could think of were the babies perishing inside her, so I took a razor blade, and with tears blurring my vision, cut off her head. Then I delivered her babies by C-section. It was my first “surgery.” Each tiny molly was placed in a watch glass, and six of the eight babies survived.

My mother was proud of me for saving the lives of these little fish, but if I had not wept, she said, she would have been angry. That’s how much she loved animals. Later, when I went off to college, she worried when I reported that my turtle, Fitzgerald (named after President Kennedy), had died. “I know you have to dissect mice all the time,” she told me, “but promise me that you will never dissect a pet, that you will never have a heart that hard!”

But my parents were changing: without our big family nearby to steady their impetuous ways, they sometimes drank too much and treated us harshly, usually apologizing later. Earlier, they had often left us for months at a time in summer camps, or with grandparents, as they went traveling. Now, if they argued, they might roar off in their cars in different directions and leave us alone for days with our maid, or with our grandfather. This was stressful because Lynda and I worried they would split up for good.

Due to my interest in science, my parents had given me a good microscope for the small laboratory that I had set up in my bedroom. So when Molly died, I preserved her cancerous tissues in rubbing alcohol and examined them under my microscope. Next, I wanted to see the difference between cancerous tissue and normal tissue, so I took a healthy molly out of the tank, killed it, and cut off the corresponding portion of her tissue, to compare with the cancerous tissue under the microscope. It was my first “cancer experiment,” and I hid it from my parents. They wouldn’t have approved.

A few months later, I noticed that the female mollies I had rescued from the mother’s second pregnancy began developing growths similar to their mother. When the next generation developed the same mysterious lumps, I suspected I was looking at the hereditary cancers I had read about. I felt this observation might be important, but I did not know what to do with my new discovery.

When I told Mrs. Watkins about my tumor-bearing fish, she encouraged me to continue studying them and to keep an accurate journal. She taught me how to enter times, dates, water temperature, diet... everything. She then suggested to my biology teacher that my fish project should be entered in the Walker Jr. High science fair. He agreed, and it won first prize — my first scientific success! I was on my way to becoming a cancer researcher. I knew my grandmother would have been proud, but had no idea how much I still had to learn. I’m grateful to Mrs. Watkins for not telling me how long and hard the road could be.

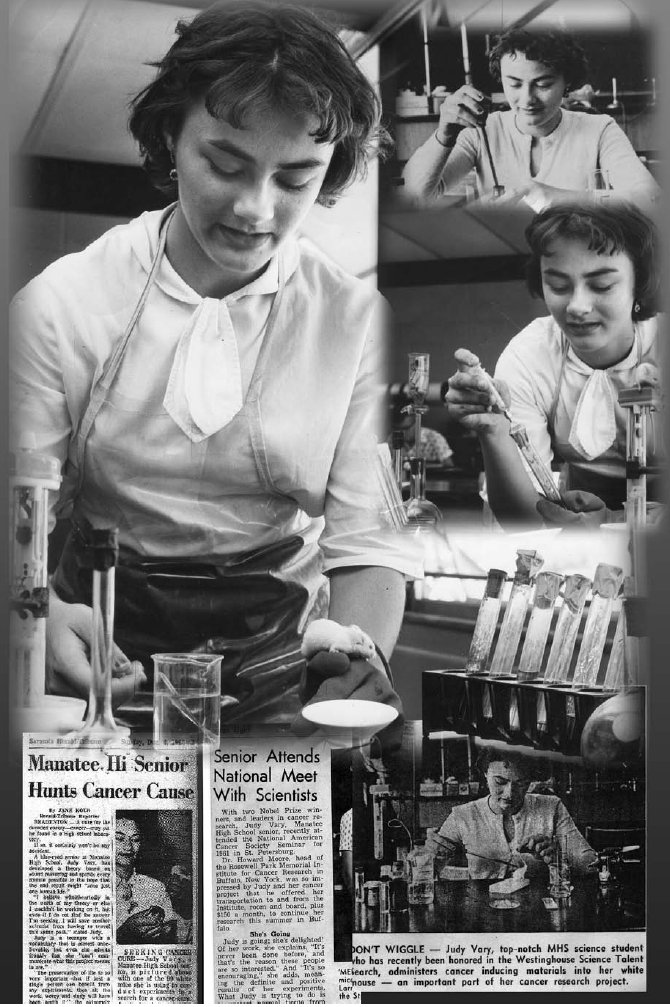

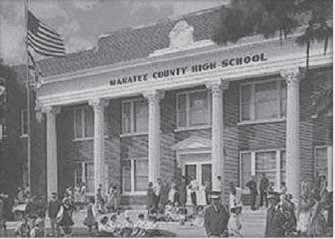

The following year I entered Manatee High School as a 9th grader and again entered my cancerous fish project in the Science Fair. I was disappointed to learn that I only placed third. Apparently, the judges felt that I had failed to prove that the fish actually had cancer, since I did not have a document from a qualified expert diagnosing the cancer. Certainly, I was not qualified to make such a determination myself. When I explained the problem to Mrs. Watkins, she decided it was time for me to meet some local doctors who might be willing to help.

“Have you been in a hospital before?” she inquired.

Yes, I said, for a year-and-a-half! Realizing that I had a first-hand view of life in hospitals, Mrs. Watkins started taking me with her to Manatee Memorial, where I met various cancer patients, doctors and staff. I observed that she never missed an opportunity to make the case for expanding cancer research in their hospital.

At the end of the school year, I turned fifteen. That summer, Mrs. Watkins received an invitation to the dedication ceremonies for a new critical care clinic in Lakeland, Florida. This was a large and impressive new facility financed with millions of dollars of taxpayer money. Mrs. Watkins invited me to accompany her to the opening of this new state-of-the-art clinic. She instructed me to bring along my cancerous fish so we could get an expert opinion. We transferred the fish to one of her Heinz pickle jars for the journey, a three-hour drive from Bradenton. There we stood in a crowd of well-dressed professionals inside this massive new hospital lobby that glistened with promise. Mrs. Watkins greeted local dignitaries who circulated through the crowd and introduced me to some of them, telling of my cancer-research project and my prizes at the science fairs. Yes, it was flattery, but she was making the point that bright young students should be recruited into cancer research.

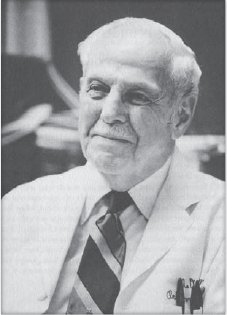

The Guest of Honor at this event was Dr. Alton Ochsner, Sr., recently president of the American Cancer Society and founder of the Ochsner Clinic, a well-known medical center in New Orleans. As he worked his way through the crowd, Mrs. Watkins asked one of her local contacts to introduce us to Dr. Ochsner. When he did, she asked Dr. Ochsner if he thought my fish had cancer. Ochsner looked at my fish in the pickle jar and agreed that they appeared to have some kind of cancer. Learning that I had harvested the tumors and examined them under a microscope, he encouraged me to continue, adding that I might want to move up from fish to mammals for my next experiments. Then with the warmth and sparkle of a professional politician, he excused himself with a sunny smile and returned to meeting and greeting others at the reception, all of whom were anxious to hear him deliver the keynote address about lung cancer.

Dr. Ochsner’s speech that day was impassioned, and it was easy to see why he had been president of the American Cancer Society. Before 1930 lung cancer was so rare, Ochsner explained, that it was not even listed on the International Classification of Disease system in the United States. Ochsner even recalled as a medical student that he was awakened in the middle of the night to witness an autopsy of a man who died of lung cancer, because his professors considered it to be a medical event so rare that he might not see another again in his lifetime.

But now, said Ochsner, there was an epidemic of lung cancer and the victims were overwhelmingly cigarette smokers. Lung cancer was a virtual death sentence for people at this time, but the link to cigarette smoking had not been proven to the satisfaction of the critics, the press or the government. There were no warnings on cigarette packages. Television and movie stars smoked freely on camera. Smoking was allowed in hospitals, offices, and restaurants. And people were getting lung cancer by the thousands.

Ochsner was the leader of a handful of determined doctors still trying to prove that smoking caused lung cancer, but their research was constantly attacked by the well-financed tobacco industry. Undeterred, Ochsner placed the blame for the huge increase squarely upon cigarette smoking, and urged us to join him in warning the public. If Ochsner’s goal was to inspire, he succeeded. I, for one, was ready to join his cancer crusade. I resolved right there to graduate from fish to mice. I wanted to prove the connection between cigarettes and lung cancer through my own experiments. I told my dreams to Mrs. Watkins, and she said she would help me. It was August 3, 1958.

It was then that Mrs. Watkins really began to help me make my project a reality. We caught mice in traps, terminated them with ether and preserved them in pickle jars full of formaldehyde. Then she taught me how to dissect them. I learned mammalian anatomy in her living room, and she bought me my first set of medical instruments for dissecting these animals. As our friendship grew, Mrs. Watkins continued to bring me with her to the hospital whenever she could. I felt like I was now part of her cancer crusade. My enemy was cancer. It had killed my dear grandmother. With Mrs. Watkins and Dr. Ochsner on my side, I was ready to defeat it. Such is the stuff of dreams, and I had plenty of them.

_____________________________________

1. My father’s relatives were skilled craftsmen, such as boat-builders, wheelwrights and professional artists.

2. Chrysler Corporation began production of the Redstone missile in Warren, Michigan, on September 27, 1954 “Chrysler lifts NASA: the next step in the rocket story” http://www.allpar.com/history/military/chrysler-and-NASA.html.

3. Those who fought in the Korean War (1950-1953) may dispute whether we were at peace. But, officially, Korea was a “police action,” and it was not treated as a real war in the mainstream media.

4. Walker Middle School (then called a Junior High School) was bulldozed to expand Manatee High School. So there is no longer a Walker Middle School in Manatee County Public Schools.

5. There were many artists in my family and I was well equipped with brushes, easels and paints. I had been drawing and painting for years by this time. I got my first set of oil paints and brushes at the age of five. My uncle Harold Vary was a professional artist and designed mobile home interiors. He also made illustrations for advertisers in South Bend. My grandmother Vary was also an artist. Her paintings paid for my grandparents’ home and estate, as during the Depression my grandfather’s boats, which were beautiful, just weren’t selling. I designed the ads for my father’s successful TV store business and even designed sets for his TV commercials, beginning when I was seven years old, and home from the hospital.

My first portrait was of my aunt Elsie, when I was nine. I included all her wrinkles, which she didn’t like, but she framed it anyway. It was done with charcoal I made myself.

6. At the time we rented an apartment in Le Chalet on Manatee Avenue called “The Le Chalet” by locals.

7. We took voice lessons from Sister Mary Cecilia, a missionary who had recently returned from China. She was yet another casualty of cancer in my early life. When Lynda and I knew her, she had already lost her right arm to cancer, and it eventually took her life.

8. There was much more live entertainment on television in the 1950s than there is today. It was common for television stations to present local acts to fill out their schedules.

9. I sang “The Lord Bless You and Keep You” in a program at Southside Jr. High School and later performed “Return to Sorrento” for a TV program shot at The Pier in St. Petersburg, FL

10. Visit SailorCircus.org to enjoy their videos. And be sure to visit their circus when you are in Sarasota.

11. Lynda was transferred to Palmetto High School in her junior year when my parents moved into a home they built nearby on Snead Island, while I continued to attend Manatee High School.