— CHAPTER 4 —

HIGHER CALLING

Religion was a major part of my life from childhood. Catholic Sisters had prayed by my bedside for months at Pawating Hospital, and they had educated and guided me through years of elementary school. I was staunchly Catholic, faithfully attended Mass, sang sacred music in the church choir, loyally took Communion, went to Confession each week, prayed on both knees, did not eat meat on Fridays, and, like many Catholic girls, guarded my virginity like it was a national treasure. The catch was that I adored boys and, frankly, liked kissing them.

I have to laugh when I remember one night in high school when I was parked with a cute boy, and we began petting. As we came close to uncharted territory, and my heart started racing, I suddenly began to worry that my virginity might be lost that very night. How could I be a good girl, if I just let go with some guy that hadn’t even married me? Thinking fast, I asked my heavy-breathing boyfriend to pray with me to seek God’s guidance about whether I should remain a virgin until we got married. That put a quick end to our adventure into the unknown.

At age 18 I was a religious girl dedicated to finding a cure for cancer, who asked for God’s guidance every day. The fact that I was now going to be trained by the nation’s finest cancer research scientists was mind-boggling: God had answered my prayers! My gratitude was enormous.

Graduation was a time to think about those critical decisions that affect one’s life forever. How could I serve God best? What would I do with this great gift of life? The best women I knew were Sisters — the outside world calls them “nuns.” Serving God — and being a scientist or doctor at the same time — would be a great way to combine the pull of the world with the desire that burned in me to follow the example of the great female Catholic saints who were heroines in my eyes. Perhaps I could eventually serve as a medical missionary in Laos, as Tom Dooley did, or in Africa, as Dr. Schweitzer did! Such were my thoughts as I prepared for the big trip north, packing my bags to spend the summer at the Roswell Park Memorial Institute for Cancer Research in Buffalo, New York (today known as the Roswell Park Cancer Institute).1

I would be enrolled in an elite student program financed by the National Science Foundation. It was very competitive. 2,000 students from around the country applied for 70 positions, but my situation was somewhat different from the other students. I would also be working in Dr. Moore’s personal laboratory on a melanoma project that Drs. Ochsner and Diehl were interested in. And Dr. Moore was the Director of the entire Roswell Park facility.

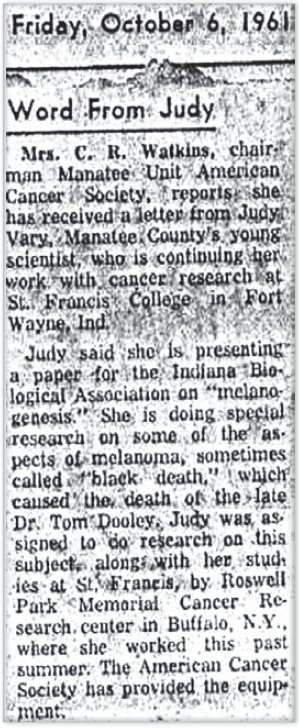

Mrs. Watkins was happy to hear that I’d be working in Dr. Moore’s own laboratory.

“I have relatives in Philadelphia,” she told me. “What if I ride the train with you as far as Penn Station? Then, later,” she added, a bit sadly, “when I come up to Roswell Park to get evaluated, you can introduce me to Dr. Moore.”

That’s when I learned that my Mrs. Watkins had made an appointment to see if there was anything that could be done about her recently diagnosed advanced cancer of the stomach and pancreas. I was shocked. Stunned. Why would God let Georgia Watkins, who had helped so many people who suffered with cancer, get cancer herself? Unfair! Horrible! I went home and cried myself to sleep.

“I’ll miss you so much, Juduffski,” my mother said. “I don’t want you to be lonely there,” she went on, “so here...” I couldn’t believe my eyes. My mother handed me a cage with two parakeets in it. I’d given them to her for Mother’s Day, and now she was giving them back to me. Parakeets! It was the last thing I needed! Daddy hugged me, then put my suitcase in Col. Doyle’s car, where Mrs. Watkins waited.

Col. Doyle drove us to the station in Tampa, and we boarded the train. I was happy to have her company on such a long trip, but inside I was gnawing on myself about her cancer. She had always been such an elegant lady — a pastor’s wife and a prominent member of the community. Now, sick with cancer, she turned stoic and courageous. She tried to be discreet, but it was hard not to notice that she repeatedly coughed up blood into a neatly folded handkerchief.

At the Tampa train station, I stood in line to purchase two sandwiches. A poor elderly Negro woman stood in front of me, but was ignored until all “whites” were served. I couldn’t believe it: they served a dozen people ahead of her. The old lady didn’t have time to get the sandwich she paid for — the train came — so, on the train, I gave her my extra sandwich. I was just so angry about it. As for Mrs. Watkins, she ate almost nothing. She was quite weak and could hardly walk. It was a long train ride. When we finally arrived in New York City, I was so concerned about her that I got off the train to stay with her until her relatives arrived. Doing so meant that I missed my connection, but it gave us more time together. Through it all, Mrs. Watkins kept a cheery smile, and reminded me that her favorite “helper” was going to become a cancer researcher! When her relatives finally arrived, I offered them the parakeets, but they declined. When they left, I boarded the next train to Buffalo with my cage of parakeets. Once in Buffalo, I caught a taxi, and thankfully, the driver was glad to take the birds off my hands.

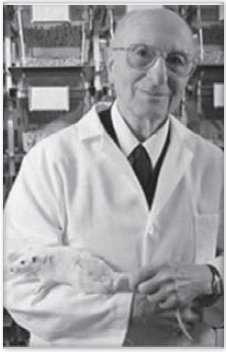

When I finally arrived at the cancer institute, I was four hours late and was welcomed by a critical voice that informed me that I was not only the last student to arrive, but that I had missed the IQ tests. This irritated Dr. Edwin A. Mirand, who ran the student program. He was a man with a very precise manner who liked things run his way and on time. To his credit, he took seriously the fact that he was responsible for the safety of the 67 students and teachers who would be working in a wide variety of cancer research projects, as well as around hospital patients who were mortally ill with cancer. But his admirable traits of discipline and responsibility did not mesh well with my growing independence, and both of us knew I would be working in the personal laboratory of his boss, Dr. Moore, which meant that some of my activities were out of Dr. Mirand’s control. I probably should have shown Dr. Mirand more respect. He was, after all, one of the nation’s leading experts on cancer-causing viruses. But to me, he was just the person running the student program.

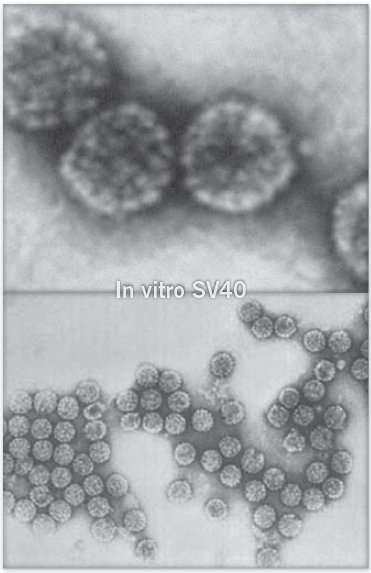

It would be appropriate to mention here that Dr. Mirand co-authored an important medical article published in 1963, entitled “Human Susceptibility to a Simian Tumor Virus.” “Simian” refers to apes and monkeys, and ‘Tumor,” of course, refers to a cancerous growth. So “simian tumor virus” really means “cancer-causing monkey virus.” Why would the medical community want to know if humans could get cancer from a monkey virus? An important question! If you recall at the Science Writer’s Seminar earlier that year, Dr. Ludwig Gross discussed cancer-causing viruses, such as SV40 (Simian Virus #40).2 SV40 had been traced to the Rhesus monkey. And the kidneys of the Rhesus monkey had been used to grow hundreds of millions of doses of the polio vaccines distributed in the late-1950s.

After releasing tens of millions of doses of the polio vaccine, the scientific establishment found that the cancerous SV40 had contaminated that same vaccine! The public knew little about these matters at the time, but the cancer researchers of the day were well-informed about potential dangers... and consequences. They all knew there was at least one cancer-causing monkey virus in the polio vaccine, possibly more. The critical question was: Did SV40 cause cancer in humans?

The coauthor of the article was Dr. James T. Grace, also from the staff of the Roswell Park. Dr. Grace had committed himself to cancer research after watching his two year old son die of leukemia. Finally, I understood their interest in me. Watching my grandmother die was “the price of admission” to this strange and demanding world, populated by committed scientists who had watched their loved-ones suffer from the common enemy they fought daily.

Dr. Grace was a warm and personable man whose primary role in the program was to teach the students to handle cancer-causing viruses safely. He taught me to propagate and handle the “Friend Virus” (an unfriendly retrovirus that caused leukemia in mice)3 and SV40 (the DNA monkey virus that contaminated the polio vaccine and caused cancer in a variety of mammals).

I was given a private room at the YWCA instead of a bed at the university dorm where the majority of females in the program stayed. The “Y” was a well-managed facility that was only ten minutes from Roswell Park by bus. As such, it was a popular out-patient residence for cancer patients being treated there. Being separated from most of the other students had the effect of limiting my contact with them after hours, and curtailing any gossip about the work being done in Dr. Moore’s lab.

Medical articles by Drs. Grace and Mirand

These articles show the medical interests of Drs Grace and Mirand in the early 1960s:

“Roswell Park Research Participation Summer Program: Implications for professional education,” J Med Educ. 1960 Jul; by E A MIRAND, G E MOORE, J T GRACE Jr

“Induction of leukemia in rats with Friend virus,” Virology. 1962 Jun; by E A MIRAND, J T GRACE Jr

“Transmission of Friend virus disease from infected mothers to offspring,” Virology. 1962 Mar; by E A MIRAND, J G HOFFMAN, J T GRACE Jr, P J TRUDEL

“Effect of chemotherapeutic agents on Friend virus induced leukemia in mice,” Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1961 Nov; by E A MIRAND, J T GRACE Jr

In the room next to me, there was a beautiful young black woman who was an opera singer. She had come to Roswell for treatment as a patient. Ironically, she had throat cancer. She was educated, sophisticated, and trained in classical opera. Plus she was always gracious and cordial to me. When I met her, she was still able to sing and spoke beautifully. I liked her and we became friends.

“Morphology of viruses isolated from human leukemic tissue,” Surg Forum. 1961; by J T GRACE Jr, S J MILLIAN, E A MIRAND, R S METZGAR

“Studies of leukemic cell antigens,” Surgery. 1965 Jul; by E A MIRAND, G E MOORE, J T GRACE Jr

“Induction of tumors by a virus-like agent (s) released by tissue culture,” Surg Forum. 1961; by E A MIRAND, D T MOUNT, G E MOORE, J T GRACE Jr, J E SOKAL

“Studies Of Leukemic Cell Antigens,” Lab Animal Care. 1965 Feb; by J T GRACE Jr, R F BUFFETT, E A MIRAND, V C DUNKEL

“Morphology of viruses isolated from human leukemic tissue,” Proc Soc Exp Biol Med; by G OWENS, S J MILLIAN, E A MIRAND, J T GRACE Jr

“Relationship of viruses to malignant disease. Part I: Tumor induction by SE polyoma virus,” Surgery. 1965 Jul; by E A MIRAND, J T GRACE, G E MOORE, D MOUNT

from the BiolnfoBank Library

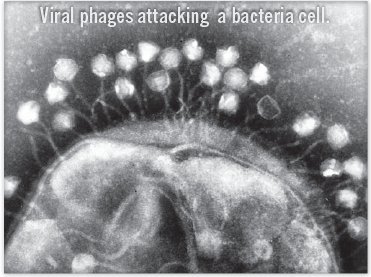

Our student program began the next day, and Dr. Mirand ran our seminars. I now saw why Dr. Mirand was selected to run the student program. His seminars were exciting and inspiring, precise and organized. He also had the “appointees,” as they called us, attend the institute’s staff sessions to learn how the day-to-day operations of a cancer research facility actually worked. After my classes, I reported to Dr. Moore’s lab for the rest of the day. Dr. Moore was a genial and unpretentious man who kept himself in good shape by playing volleyball or basketball with the staff. But his work was his world. Once he got into his laboratory, he became uncommonly focused. Dr. Moore was also the director of the entire institute. So he came and went at will and left the day-to-day management of affairs in the lab to Dr. Haas and his wife, with whom I worked closely on a daily basis. Also part of this group was a brilliant college student named Art. This was his second summer working in Dr. Moore’s lab, where he was wrapped up in the study of bacteriophages — viruses that destroy bacteria — which we believed could be adapted to selectively attack certain kinds of cancer cells in the body. This area of research continues to show promise today, which shows how far ahead of his time Art really was.

Ongoing was a project to develop a liquid medium to keep cancer cells alive — a difficult task at the time. I worked with Dr. Moore and associates that summer in helping develop the basis of what is now the famed RPMI medium, still used worldwide to grow cancer cells in test tubes. By the end of that summer, I knew how to create these advanced mediums, which could keep cancer cells alive no matter where I ran a lab. That’s important to remember in this story.

James A. Reyniers

Bacteriologist James A. Reyniers pioneered the development of germfree animals for scientific research at the University of Notre Dame over a 30 year period. Virtually all the germfree colonies now multiplying in a dozen medical centers on four continents are either descended from Reyniers’ stock or were developed using his methods.

I had just begun my work when I received a phone call from Dr. Reyniers in Tampa. He had finally returned from his trip and had gotten my message about going to Roswell Park for the summer. He congratulated me and asked me to pass his regards on to Dr. Moore and his staff, many of whom he knew well. It was nice to be able to pass “regards” from someone so well-known to Dr. Moore, who said, “You do get around.” Such social networking is as important in scientific careers as in any other. I promised myself that I would repay the favor to Dr. Reyniers one day if I could.

Originally from Chicago, Reyniers was expert in the use of machine tools, a skill he learned in his family’s business. He used these skills to develop laboratory equipment, such as isolation chambers for handling highly pathogenic organisms. He called himself a “bacteriological engineer,” and it was said that his machine shop often dwarfed his laboratory.

Reyniers constructed a portable isolation system which integrated mechanical air filtration, steam sterilization, and specially constructed chambers. The military application of this technology was for biological weapons research in the 1940s. Records from the National Archives list him as participating in biowarfare research at that time. According to a 1961 article in TIME Magazine, Reyniers left Notre Dame in 1959 to set up the Germfree Life Research Center in Tampa, Florida, where he concentrated on the mysterious role of viruses as causes of cancer. He also coauthored an article on viruses in Japanese quail eggs in 1962 for the Laboratory of Viral Oncology, National Cancer Institute, U.S. Public Health Service, Bethesda, Maryland.

On many levels, this summer would be a rough emotional experience — a baptismal immersion into the tragedy of cancer. Day after day I saw people in the most advanced and dreadful stages of the disease, fighting for their lives. I saw patients exposed to radiation and injected with toxic chemicals in the attempt to poison their tumors. I saw their limbs amputated and their organs removed. I watched people die on the operating table. I saw patients so addicted to cigarettes that even when their cancerous tongues and jaws were removed, they still refused to quit, smoking their cigarettes through the red, wet hole that remained!

The laboratories at Roswell Park used animals for their experiments. I saw their suffering in a new light. I could see the sadness in their eyes as they looked upon a world composed of metal walls, monotony and pain. There was no hope for them. I saw their fear when their human keepers approached. One day my assignment was to watch five sedated dogs get ‘de-barked’ by having a hot cauterizing iron thrust down their throats to burn out their vocal cords. They could no longer bark, but they could still whine.

The animals were often shaved and wrapped in bloody bandages. One German shepherd mother had five puppies following a surgical procedure that removed her right lung. Nobody had guessed she was pregnant. She licked her newborn puppies clean, despite the agony imposed on her, only to watch them taken away. The sorrow in her eyes haunted me.

These experiences had a deep emotional impact on me. I felt guilty about the marmoset monkeys we were killing that summer in Dr. Moore’s lab, and for the first time questioned the ethics of what I’d done to all those mice back in Bradenton.4 A new part of my soul was beginning to open, and I became acutely aware of how much pain filled the world, like watching smoke slowly fill the hallway in a burning building.

About mid-summer, Mrs. Watkins arrived in Buffalo for her evaluation. It was good to see her, until she told me that the doctors had found that her cancer — already deadly — had now metastasized to both her kidneys. At her age, kidney transplants would not be a viable option. She knew her condition was terminal and understood, better than most people would, the sentence she had just received. She now faced the certainty of a slow, gruesome death.

There was nothing for her to do but go home. Needless to say, we had a long, sorrowful goodbye. Georgia Watkins had been the one who had started me on this path. She had been the one who helped me, encouraged me and trained me. Even in this dark hour, her confidence in my future remained unshaken: I would find a cure for cancer! Her life’s work would not have been in vain!

I wept as she left, but I was now more determined than ever to fulfill Mrs. Watkins’ prophesy and make her proud of me. Full of new resolve, I began staying later and longer than any of the other students at the labs, and took on extra projects. I gave myself little time for frills or fun.

I stopped attending the special weekend activities, such as canoe trips and visits to nearby Niagara Falls, which were intended to break the stress. Instead, I began reading cancer research journals, even tackling those written in foreign languages. Remembering how Dr. Reyniers had helped me, and hoping to donate to his cancer charity (“Research, Inc.”), I purchased art supplies on my slim budget and began painting: I’d sell paintings to help his cause! Good luck was with me: while jogging near the “Y” for exercise, I discovered D’Youville College. I was allowed to set up a little studio after making friends with some students there. The College soon agreed to put my paintings on display to help raise funds for Dr. Reyniers’ charity.5 Particularly striking was the high quality of the medical technology program run by this small Catholic college, which had been founded by Ursuline nuns. “Small” did not mean “inadequate.” I remembered that I’d been offered a full scholarship by St. Francis College — a small Catholic college in Fort Wayne, Indiana. I now learned that St. Francis, too, had an excellent medical technology program. D’Youville was so friendly — and so Catholic — that I began to spend my Sundays there. I was beginning to reconsider those plans to attend Purdue University.

As the days passed, the cancers that surrounded me seemed to be closing in. My friend, the lovely opera singer who lived in the room next to mine at the YWCA, was losing her battle. As the cancer — and the debilitating radiation she was getting — pulled her down, she became a ghost of her former self, not only losing her singing voice, but even her ability to speak above a whisper. Yet she thanked God for each day that she was able to utter a single word. It was unmistakable that she was dying. The dignity with which she faced her ordeal humbled me.

Another woman living down the hall from me at the YWCA had brain cancer, and they had surgically removed the cancerous part of her brain. Now she suffered from sudden, dangerous seizures. In the middle of the night I would hear her scream, and rush to her room. By using a tongue depressor, I was able to keep her from seriously biting her tongue, but I didn’t sleep well for fear she’d seize and I’d not hear her. As we neared the end of the student program, I had a final report to prepare for a seminar, which required long hours of work in an alert state. I wasn’t getting enough sleep. Then, on a D’Youville bulletin board, I noticed there was a room for rent in a nearby building above the art gallery. After talking to the landlord, I went back to the YWCA and got my things.

I had no idea that anyone would be upset, for the doctors never came near the ”Y.” But they were. Somebody must have ratted on me, because Dr. Mirand and a friend of his went looking for me immediately, frantic with worry. He thought he had lost a student! I probably should have told him what I was doing, but I didn’t. Before long, they found me in the little garret room I’d rented, enjoying my spaghetti dinner straight from the can. Dr. Mirand, his face pale and his countenance furious, demanded my immediate return to the YWCA. “This place is a mile away from the Y!” he fumed. “We put you in the “Y” because it’s only ten minutes away from the labs, so you can get more work done. That means, stay put! Those are the rules!” It was an order I had to obey.

I told Dr. Moore about the incident the next time I saw him, hoping I might position it in a better light than Dr. Mirand would. But Dr. Moore had far more serious things on his mind. He just chuckled at my story and said it was good that I gave “Edwin” something to fidget about.6 The important thing was the work on melanoma that I was doing in his lab. He added that I did not need to continue in Dr. Mirand’s program if I didn’t want to.

The only place where I felt normal at this point was working in Dr. Moore’s lab with Dr. Haas and his wife. It was where I belonged. One day we were discussing a young woman who had worked in their lab the year before: “What a waste!” they griped. “She became a nun!” I knew Dr. Haas and his wife were devout Catholics, so I was curious about their comment.

“Is she not going to become a scientist, or a doctor?” I asked.

“Yes, she still is,” replied Dr. Haas, “but she’ll never have children.”

It was this comment that gave me the idea that I could be both a nun and a cancer researcher at the same time. Committed to finding a cure for cancer, and attracted to the idea of becoming a medical missionary for the Catholic Church, as had Dr. Tom Dooley, I’d not seriously considered becoming a “Sister” and a cancer research scientist. The idea was compelling. Peace and serenity! Life in a community that would always support my cancer research! I began to mull over what the doctors had told my mother when I was ten years old — that I’d never have children. Sadly, for the first time I realized that if I got married, the man I’d marry would be deprived of the massive joys of fatherhood. If I really loved that man, how could I let him marry somebody like me?

About this same time, Dr. Moore told me that Dr. Diehl was coming for a visit, and would be a guest at a dinner at Moore’s home. Some students would be there, and he hoped I would come too, if I was free. If I was free? As if “No” was even an option. Yes, yes, yes, I would be there!

That evening Dr. Moore drove me from the lab to his beautiful home. The weather was perfect, so we ate outside on a patio in the back overlooking a lush wooded creek. Including myself, there were about fifteen students from the National Science Foundation program.

It was good to see Dr. Diehl again, and he was gracious and warm as usual. After dinner Dr. Moore took me aside to meet with Dr. Diehl in his study to discuss my future plans.

I was quite happy to have their interest and liked what I heard. They wanted me to continue my own research, instead of abandoning it and going to college as a normal freshman. Given that nothing was normal about my education at this point, the possibilities seemed limitless. I agreed with their suggestion, then told them about my desire to serve both God and humanity, perhaps as a combination doctor and nun in the Franciscan order. There I could devote 100% of my life to the fight against cancer. I told them about an offer sent to me by Saint Francis College (now the University of Saint Francis) in Fort Wayne, Indiana.7 They understood that I was sincere, and took my proposal seriously, but they also exhibited a gentle fatherly concern that I might change my mind about “the nun thing” in time.

Dr. Moore and Dr. Diehl discussed my proposal and evaluated how it might impact the funding they had envisioned for my research. After some deliberation, they suggested that I could spend a year or two at St. Francis, before moving on to the University of Chicago. After all, St. Francis did have a fine medical technology department. They could arrange for grants, they said, to support a laboratory there for my use, so I could continue in my present course of research. I had just begun working with monkey viruses and radiation, under Dr. Grace, and was anxious to merge that new knowledge with my present work — facilitating the most rapid growth possible of human-based melanomas, in variants of our new, ground-breaking RPMI mediums. Dr. Diehl suggested that I could compare the growth rates of human melanomas infected with SV40 with that of uninfected human melanomas to determine what would make these fast-growing cancers even more deadly.

I was taken aback. Wasn’t that just the opposite of what we were supposed to be doing?

“The key to defeating cancer is to understand it,” Dr. Diehl reminded me. “If we learn what makes cancer more deadly, instead of what makes it weaker, we’ll be forging ahead in brand new territory.”

I understood. It was a “top-down” approach. What made cancer more deadly might just provide the key we needed to know how to defeat it.

None of this would interfere with any plans having to do with becoming a nun, they told me. And I’d be far away from my parents in Bradenton, and all their problems, which was what I wanted. That night, I wrote to Admissions at St. Francis College and accepted their offer. I would start in September, only weeks away. I also wrote to Purdue and formally declined their generous offer.

By the end of the summer training program, I had presented three papers to the program appointees and staff at Roswell Park.8 Even Dr. Mirand begrudgingly complimented me on the quality of my final presentation at the last seminar session. “I don’t know how you do it,” he muttered.

As a result, I received several awards, including a grant from the National Science Foundation for my college tuition. Further, lab equipment and supplies would be sent to me, care of a lab in Fort Wayne, from the National Cancer Institute and the American Cancer Society. I would be getting a new strain of specially bred bacteria-free mice, tissue cultures with cancerous viruses like SV40, and cancerous tissues derived from human cells, like melanoma.8 This is where Diehl and Ochsner wanted me to focus my research efforts. It would be quiet, low profile, with little red tape. Everything was set.

My parents called to tell me that Sister Mary Veronica had sent a letter. They were thrilled that I was going to attend a Catholic college. My time at Roswell now drew to a close, and yearning to see family and friends again before going to Fort Wayne, I took the train down to Tampa where I would then transfer to a bus for the final leg to Bradenton. But I had business in Tampa first. Dr. Moore had asked me to stop in and see Dr. Reyniers to arrange to get mice for my lab.

It was good to finally meet Dr. Reyniers in person, and I told him about donating the profits from my paintings to his research charity. In return Dr. Reyniers gave me a voucher I could use to get mice for the new laboratory I would be setting up at St. Francis.9

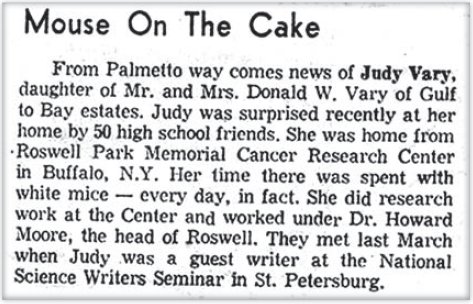

This stop in Tampa took longer than I expected. I had stopped in to see my grandfather who was in a hospital there. Grandpa had been exposed to mustard gas in World War I and had problems with his lungs. I missed the next several buses, and when I finally arrived back in Bradenton, my father picked me up at the bus station and brought me home... to a surprise party! My father had thrown a feast! Our house was jam-packed with friends. Two local beauties, Miss Manatee County and Miss Manatee County Fair, were there. My mother had bought a large cake topped with a white mouse sculpted out of frosting. Reporters and photographers from the local newspapers collected names and took photographs, and more articles appeared in the press about “Judy and her cancer research.”

But my visit was brief. A few days later, in early September, 1961, I kissed my family goodbye and took a bus back to Tampa. There I boarded a train headed for Indiana, looking forward to setting up a lab as soon as possible that would be capable of handling the precious cancer cells that would soon arrive from Roswell Park.

Upon arrival at St. Francis College, I signed up for a full load of premed courses with organic chemistry, anatomy and physiology, math and a required English course taught by Dr. Fink! There’s a name you don’t forget. I quickly got into a religious routine by attending Mass every day.

By this time, I knew not to gossip about my work with other students. So I had the public face of a college freshman, and a secret life as a cancer researcher working on accelerated projects for the top scientists in that field in the country.

I settled into a room in the dormitory with two roommates. One of my roommates was a large girl with pendulous breasts and over-sized underwear. We were not close and I don’t even recall her name. The other roommate, however, was quite memorable. This was Marilyn, an attractive girl armed with both a keen brain and a good sense of humor. Like me, she intended to combine medicine with a life of service to humanity, and was enrolled in premed classes, so we shared similar schedules, classes and interests. Every bit as religious as I, Marilyn told me how she had rejected her previous pursuit of earthly pleasures to pursue a higher purpose in life. She not only admitted she wasn’t a virgin, but at night, after our third roommate fell asleep and began to snore, Marilyn would lie on her bed and recount her romantic adventures with various boyfriends, including intimate carnal details.

I was curious, as any girl would be. Marilyn was a gifted storyteller who laced her riveting tales with outrageous comments and delicious details. One comment stayed with me: as our roommate snored away, Marilyn said, in a stage whisper, “Sex! Yes! I loved it!” Then, with a deep sigh, she confessed, “The angels! They don’t know what they’ve been missing!”

Marilyn became my closest friend at St. Francis. We both joined the choir and sang at Mass every morning. We both groaned over our comparative anatomy class, run by a tyrant nun. My small lab was now ready, but I still had no mice, so while waiting for their arrival, I had time to explore St. Francis’ idyllic campus.

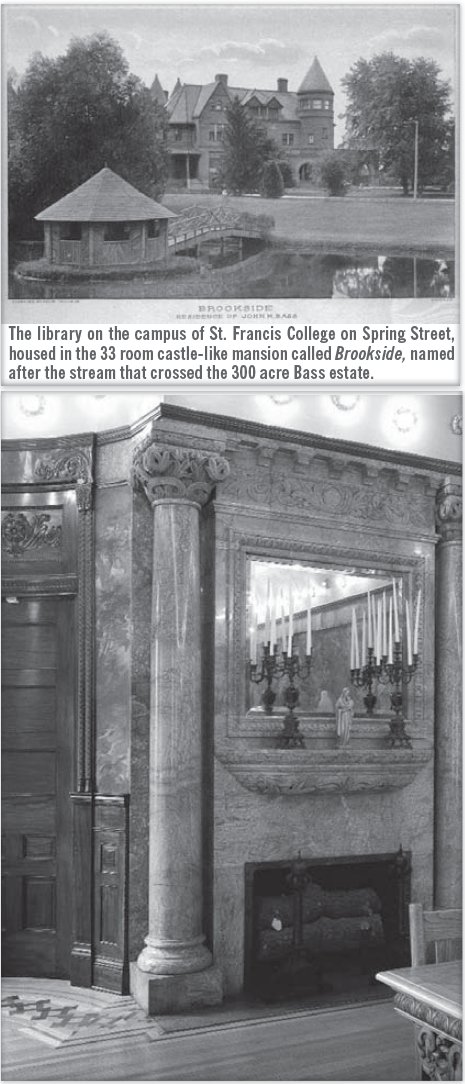

The architectural centerpiece of St. Francis is called “the castle.” It was a lavish Victorian mansion built of sandstone in 1902 by industrialist John H. Bass, who became one of the wealthiest men in America by making wheels for railroad trains in the late 1800s.

The interior of the Bass Mansion was elaborately paneled with irreplaceable hardwood. In its center was an exquisite reading room with ornately carved cabinets holding treasured book collections. Carpeted stairs coiled down to a Gothic abyss of a basement where a huge collection of books, many very old, filled shelf after shelf in a labyrinthine maze. Hardly anyone was ever there, and the air was thick with silence. There was an occasional lamp, with an over-stuffed chair nearby to curl up in.

Among this historic collection, I found treasures like a first edition of Milton’s Paradise Lost, which I took from the shelf and started to read before I even reached the chair. At first, I eagerly inhaled it at my normal speed-reader pace, but soon I was reading slower and slower, as I was drawn into the depths of its beauty. I had finally found my sanctuary, and frequently returned to immerse myself in the mesmerizing solitude of those silent, subterranean rooms throughout the semester. Sometimes I would find myself reading alone into the night, feeling the great stone building shrouding the depth of human experience that lay between the dusty covers of the priceless collection. Here I read some of the great classics of Western literature: Blake, Dante, Hugo, as well as Russian authors like Pushkin and Dostoevsky. Some of the Russian works were published in dual language editions, so I got to practice reading in Russian to keep my meager skills alive.

It was great to be able to read literature instead of medical books, and to have a place where I could read in solitude. I relished my freedom from the daily control of my obsessive parents, and the meddlesome Dr. Mirand. Between the medical program, the religious atmosphere, and living in a tightly knit community of smart respectable young women, I felt I had really found my place in the world. I was on the road to having everything I had ever dreamed of.

But the American Cancer Society and the National Science Foundation were not paying my tuition and expenses so I could worship God, read Russian novels and listen to Marilyn’s romantic adventures. I had work to do, involving cancer-causing monkey viruses like SV40 and human cells with melanoma. To this end, I had two laboratories. My main lab was not even on campus. It was housed at a nearby hospital, which was a convenient public front where things like radiation and handling viruses were not unusual. And it was just a brisk walk from St. Francis. The fact that the hospital had two new buildings under construction created an atmosphere of chaos that made it easy for me to slip in and out of my lab. I was hardly noticed, as the hospital was doubling in size with many new faces on the staff.

My concern about being noticed had to do with the fact that I was a minor who was officially not supposed to be working with viruses and radiation.

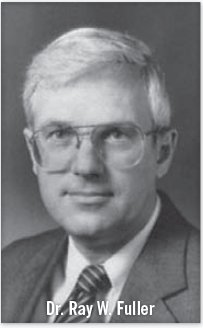

So not only did I try to keep a low profile around the hospital, but the paper trail for my project had to be protected. All items for my laboratory projects were shipped to me in care of a doctor in town. The doctor was Ray W. Fuller, a young biochemist who had just received his PhD from Purdue.10 Fuller was the first director of the Biochemistry Research Laboratory at the Fort Wayne State Development Center (a mental hospital), where he developed psychoactive drugs. Aware of the fragility of his new position, Fuller was anxious to please persons such as Dr. Diehl – the American Cancer Society’s Vice President in charge of research, happily receiving shipments for me. In some cases, his lab actually did some of the initial processing of the cell cultures. After two years in Fort Wayne, Fuller officially joined the Eli Lilly company where he spent the next 33 years of his career. Today, Dr. Fuller is best known as coinventor of Prozac, the psychoactive drug that earns billions of dollars each year for Eli Lilly.11

I am not exactly sure how the chain of communication worked in Fort Wayne, but it appeared to involve Dr. Fuller, Eli Lilly, Roswell Park, and the American Cancer Society, all of whom were on our cancer team at the time. Bank-shooting deliveries through Dr. Fuller made it hard for anyone on the outside to trace the exact supply route to me. Since I was still a minor and was not supposed to be handling these types of materials without proper supervision, the paperwork said a qualified adult, Dr. Fuller, was my supervisor. The goal of my experiments was to see if the onset of melanoma was affected by the presence of SV40 (the monkey virus that had contaminated the polio vaccine). If I could learn under what circumstances the SV40 virus affected melanoma development – if indeed it did – perhaps I could then manipulate the virus to see what effect that had on melanoma development. At this time, I did not know that many thousands of people had actually been injected with the contaminated vaccine. The very thought of releasing that kind of loose cannon into masses of trusting people would have disgusted me. Aiming at the mechanics of the SV40 virus itself to make it fight cancer was a bold idea.12 And if it worked, it would be what Dr. Ochsner called “Serendipity!” Cancer cells containing the SV40 virus arrived by early October 1961. They would be soon be followed by monkey kidney cells, through which the SV40 virus had spread like a fungus on old bread.

At the state hospital, Fuller’s team processed my deliveries. They stabilized the tissue cell cultures in what today would be called a highly recommended precursor of RPMI 1640 (that’s 1,640 variations of the medium that Dr. Moore and his assistants, such as myself, tested before the standard RPMI medium was perfected in 1967). When the cells were determined to be safely growing in the medium, it was sent to St. Joseph’s Hospital — not far from St. Francis College — where I worked with the tissue cultures in their sparsely furnished oncology lab. I also brought cell cultures from that lab back to the St. Francis campus where my second lab was located. It was small and modest, but adequately equipped to nurture the cell cultures.

My initial task was to continue one of the three Roswell Park projects — growing hamster cell cultures in which a modified human melanoma had been established. I was testing a variety of RPMI mediums to determine which medium might speed up melanoma growth. Within two weeks, I revved the melanoma in those hamster cells into metabolic high gear. My reports were sent to Dr. Ochsner, who never acknowledged my communications directly, but I soon received his response — human melanoma cells from Buffalo.

I was told that these melanoma cells were from the cancer that had killed my then-hero, U.S. Navy Dr. Tom Dooley, Jan. 18, 1961. He’d written several popular books combining his strong religious and anti-Communist views with commentary about his work as a Catholic medical missionary in Laos and Southeast Asia. His dying statement struck me to the soul: “The cancer went no deeper than my flesh. There was no cancer in my spirit.” Dr. Moore knew how much it meant to me to be able to work with this line of cells. They were ID coded because efforts were being made to make Tom Dooley a Saint in the Catholic Church, and the New York doctors who harvested Dooley’s melanoma didn’t want anybody ‘worshipping’ a cancer cell line. (It would be another two years before I learned that Tom Dooley was a CIA asset who had indulged in homosexual activities, from another famous Catholic who was also a homosexual: David W. Ferrie.)

Tom Dooley

Thomas Dooley III (January 17, 1927 — January 18, 1961) was a physician in the United States Navy, who became increasingly famous for his humanitarian and anti-Communist activities in Southeast Asia during the late 1950s when he authored Deliver Us from Evil and two other popular anti-Communist books.

In 1959 Dooley returned to the United States for cancer treatment; he died in 1961 from malignant melanoma at the age of 34. He was awarded a Congressional Gold Medal posthumously and President Kennedy cited Dooley’s example when he launched the Peace Corps. There were unsuccessful efforts following his death to have him canonized as a Roman Catholic saint.

— Wikipedia

I started growing these melanoma cancer cells in my lab and spent more and more hours there. I also continued to send Dr. Ochsner monthly reports throughout the fall, as he instructed, though he never responded with questions or comments about them.

My college classmates wondered why I was allowed to keep such late hours, as it was uncommon in such a strict Catholic girls school. But I did have a social life and was able to go on road trips to Notre Dame football games to meet boys. And I landed a part in a school play, where the daily rehearsals gave me some recreational fun. I also got a part-time job working as a switchboard operator at the school’s rectory. Meanwhile, mid-term exams came and went.

As I explained earlier, the suffering and sorrow that I had witnessed at Roswell Park had a profound emotional effect upon me, and it had merged my desire to fight cancer with my desire to serve God. My current situation posed the question: who was I really working for: Dr. Ochsner, or God?

I yearned for a peace that I did not have. I resented being ordered around by officious doctors who were treated like gods by their staffs, and who sometimes did play God with human lives. Further, I resented the way they sat around and drank wine and plotted how they could use me to get grant money by moving me hither-and-yon. Was this what I’d worked so hard to attain? Was I just a pawn in the “Great Cancer Research Machine”?

Becoming a Sister of St. Francis offered an alternative. It would give me the opportunity to serve God, fight cancer, and prepare me for broader service to humanity, such as being a doctor to the poor and sick in Africa.13

After a lot of prayer, I took the leap of faith and went to Sister Veronica, the Director of Admissions, who had become my confidante. We prayed together, and then we talked. Sister assured me that I could join her Order and still pursue pre-med studies and cancer research after that. Amazingly, they had missionaries in Africa, as well. I think her crowning statement was that this Order’s home convent was located in Mishawaka, a suburb of South Bend, Indiana. When I grew old, I could retire in the city of my birth! It was, I felt, providential: I made my decision.

She accepted my request and immediately ordered me to lower the hem of my skirt and stop wearing shorts and slacks. The next thing she did was insist that I take daily baths! I already took showers each evening because I worked in cancer laboratories and that was part of basic daily hygiene, but now she required that I bathe in a tub every night. And, I mean, she checked on me nightly! But I supposed that taking baths would please God, or if He didn’t care, at least it would please Sister Veronica.

The plan was for me to enter the Order of St. Francis in February of the next year. I didn’t tell anyone except Marilyn. She had similar dreams for her life, and we decided that we would enter the order together on the same day, Feb. 2, 1962. I felt I had a new ally in my quest. Together, we would use our brains and industry to reduce the suffering in this world.

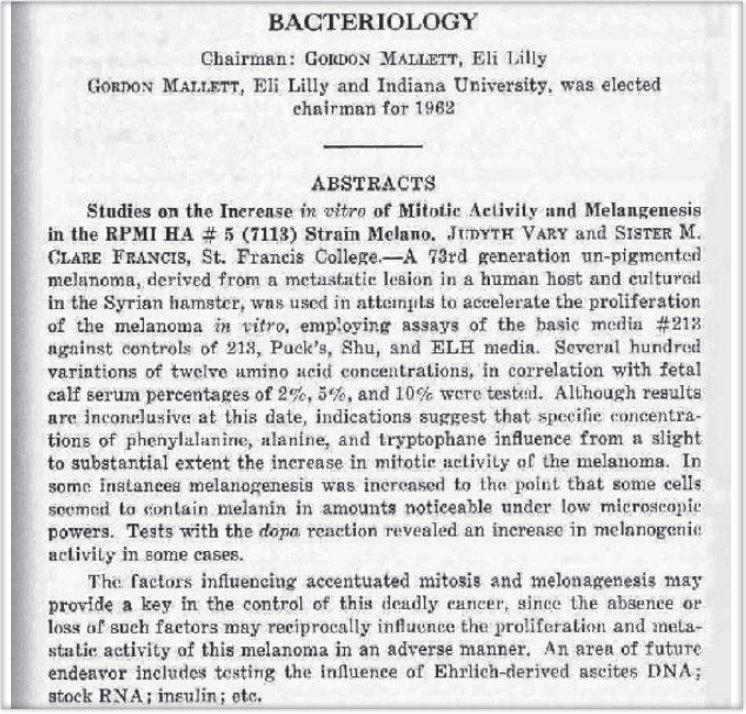

On October 19, 1961, I went to Terre Haute, Indiana, accompanied by several sisters from the Order of St. Francis. We travelled to Indiana State College for the fall meeting of the Indiana Academy of Science. One of these kindly and intelligent nuns was a doctor, and two were highly-trained medical technologists (or maybe it was the other way around). They came to co-sponsor my presentation because I was a minor. There I delivered a paper on melanogenesis (melanoma cancer growth) for peer review to the Committee on Bacteriology14 and to members of the informal organization that had originally invited me — “The Indiana Biological Association.” The title of the paper (“Studies on the Increase in Vitro of Mitotic Activity and Melanogenesis in the RPMI HA #5 (7113) Strain Melano”) summarized both the work I’d done at Roswell Park with melanoma, and, as the abstract indicated, recent success in getting this human-derived melanoma, which had been grown in hamster “volunteers,” to become more deadly.15

The paper was accepted and the abstract was published in the 1961 Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science on page 71. It was my first science paper to be accepted for publication in a peer-reviewed journal. For that, I was happy: a perfected version of the paper was scheduled to be sent to the Academy at the end of the month.16 But bigger targets loomed.

The next step in my cancer research project was for me to try to transfer the SV40 monkey virus to human melanoma cells to see what the result of their interaction would be. The monkey kidney cells laden with SV40 would be arriving in about a week. Then there was a pause in my schedule, and I had a moment to ponder my family in Florida. What would my mother and father say?

At first I kept my decision to become a nun secret from my family. It was, after all, my life. Yes, I was headstrong, but my parents were too, as well as opinionated and determined to control my life. The fact that my entire college education would be paid for with grants that I had earned myself would have impressed most parents; but to my father, it was just further evidence that I was no longer under his control. What would he say when he heard that I had a new father and his name was God? After agonizing over it, I decided to write and tell them about my plans.

Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science, 1961, p. 71

This abstract of an article was written by Judyth Vary under the direction of her supervisor of research at St. Francis College. It was published in the Indiana Academy of Science in 1962. It deals with preparations for the enhancement of melanoma cancer growth in a strain of modified hamster cells from Roswell Park (as the RP in the RPMI HA #5 indicates) at St. Francis College in 1961.

As soon as my father read my letter, he called me on the phone. He was furious. “They’ve brainwashed you!” he seethed. “They just want you to work for them for free! And you didn’t have the guts to tell them to go to hell, did you?”

He claimed that my life was no longer my own, that I was being controlled by others. He attempted to twist this into a character deficit on my part, saying I did not have the courage to choose for myself. But I knew I was choosing for myself and that’s what he hated. He wasn’t in control!

We argued bitterly on the phone. “You were created by God with a body that shows you’re supposed to get married,” Dad went on. “Think! You could be the wife of a successful doctor! And have children!”

“I’d never carry babies when I could carry clipboards!” I replied, trying to stand up to him. “And besides, you and mama told me yourselves that I can’t have babies, so why marry?”

Frustrated by his lack of power over me, my father stated in blunt language that I did not have his permission to become a nun. He commanded me to withdraw my application to the Order of St. Francis. To that I had just one answer: “No! You can’t make me!”

That’s when Dad hung up on me. I knew my family would be horrified that I had defied him, had “talked back” to him. It was something never done in our family. We had been taught to respect our parents and to obey them, even if they stood before us in a drunken stupor.

I walked back to my dorm room feeling determined and victorious. I had stood my ground against my father’s rude interference in my personal life. Flinging open the door, I saw my sweet, funny roommate Marilyn sitting on the floor by her bed, motionless. Her normal sparkle was gone. She was staring at the floor. A terrible foreboding swept over me. “Marilyn, what’s the matter?” I asked, my voice trembling. As I sat down next to her, she looked up at me with tears in her eyes.

“I have cervical cancer,” she said flatly.

The simple sentence hit me like a ton of bricks. I was devastated. Cancer’s ugly face had burst into my personal life again. And this time it was someone young and beautiful, in the prime of her life; someone with great dreams and goals. How many times would this happen to people close to me, and why? More than ever, I realized how fragile life is. I asked her if she was still going to enter the Order. Yes, she would. It was up to God to decide what would happen to her. I told her that I would be right beside her on that day.

On October 28 I had received the SV40 virus-laden cells, and was looking forward to transiting the virus into hamster cells, then into live mice, to see what would happen. And my HA melanoma strain would hopefully soon be infected with the same mysterious virus. On October 29, my cancer cell lines and all those other goodies were tucked in for the night in nice, warm plastic flasks. Nothing would need attention for 48 hours, so I had time to concentrate on my part in the school play which would open on Nov. 1 - All Saints Day.

That evening I headed to my part-time job where I worked at the switchboard to earn pocket money. It was late, and I sat at my station rehearsing my lines for the play and watching the clock. I only had about 15 minutes left on my shift. Suddenly, the door opened and in walked my father.

“Daddy!” I exclaimed.

“Judy, you’re coming with us,” he commanded.

“But I’m not finished with my shift!” I protested.

“I don’t care about that. Let’s go,” he said as he grabbed me by the arm. Through the window, I saw my mother standing by the car, with Aunt Elsie and her son Ronnie sitting in the back seat.

“What are you all doing here?” I demanded.

“We’re taking you home.”

“You can’t do that. I’m in the middle of a semester. I’m doing research and I have a part in a play that opens in two days. I can’t leave!”

“You are a minor, and I am your parent. I have legal control over you and your whereabouts. You don’t have my permission to be here. And if you don’t come with us, I will have you arrested as a runaway and returned to Florida in hand-cuffs.”

With that he made me get in the car, saying they had already been to my dorm room and gotten my clothes. Without further ado, he started the car and immediately drove us off into the night back to Bradenton, Florida.

I protested furiously as he drove off and appealed to the others to help me. They would only say that my father was my father, and it was his decision to make.

“You’re ruining my life!” I said with venom. “Why are you doing this?”

“You brought it on yourself, Judy,” my father said, breaking into an obviously rehearsed speech. “We’re not going to lose you to a convent while you are still a minor. You are too young to make those kinds of decisions for yourself. We have to protect you.” Then my father mocked my protests by saying I was not acting like the quiet little nun I said I wanted to be, and ended with “Where is your respect for your elders?”

The long hours of driving through darkness were torture for me. I could not believe my own family had kidnapped me, and that they had the legal right to do it! I had been betrayed by the very people I should have been able to trust. I was angry and bitter, and I started to feel real hatred for the first time in my life.

It wasn’t until we finally arrived back in Bradenton that I realized the clothes they had grabbed from my dorm room belonged to my buxom, overweight roommate. My entire wardrobe was still in Indiana! All I had to wear were a bunch of baggy clothes that were way too big. My father told me I didn’t need more clothes because I would not be going anywhere.

Once inside the house, my father marched into my room and removed the telephone so I couldn’t call anyone. He told me that if I left our property without his permission, he would have me arrested as a runaway. Then he fixed himself a drink.

The next day Sister Veronica called our house, pleading with my father to allow me to finish the semester, but to no avail. I begged him to let me go back. Was it really necessary to derail my education and ruin my career, just to “save” me from the nunnery? “I’m not concerned about that,” Dad answered. “All a girl needs in this life is a high school education and a good body. Don’t tell me how ‘important’ education is to you. In a few years, you’ll forget all about it. Your hormones will make that decision for you.”

I ground my teeth with the anger I had been taught to always repress. Where was God? Where was God’s power? How could God let this happen to me? How could He allow cancer to destroy all my loved ones and then, when I offered my very life to Him, let my parents have their way instead? Ever since I was that small child in the hospital with the nuns, my greatest fear had been that I might one day lose my cherished faith. Now, I teetered on the brink.

Isolated, mocked, and feeling helpless, I remained in my room, tearfully pleading with a silent God who was failing me. Dad didn’t help matters by giving me a stack of anti-Catholic literature. “Read it and weep,” he said. I knew Dad had only converted to Catholicism in order to be accepted by my mother’s Hungarian family. Reading those anti-Catholic books and pamphlets ripped my soul.

That’s when I lost my faith not only in God, but in the very idea of religion itself. Who was I, then? Just the result of an egg and a sperm that collided in a womb? I was left staring at the rude outline of barbaric life itself: animal eating animal; humans bombing humans, bodies eating themselves. I felt forsaken, burned alive like Joan of Arc. Nature stood before me, “red in tooth and claw.”

Was I merely a piece of flesh waiting to be eaten? Were we all merely a bundle of chemical reactions to be reduced to scientific analysis? Was life itself just a Darwinian game that would eventually decide who was “fittest”? Life without faith was life without purpose. Did the power to kill equate to the right to kill? The specter of life without love, without faith, and without a higher purpose stood before me. It was a terrifyingly lonely experience: a thunderous vision that made me ache inside. Suicide might end my pain, but it would not answer my questions. Having my faith stripped away from me was the spiritual equivalent of rape, and my family didn’t even seem to care.

___________________________________________

1. See sidebar on page 49 about Roswell Park Cancer Institute.

2. Ludwig Gross, BH, Mar 22 or so, 1961.

3. The Friend Virus is a strain of leukemia virus infecting mice and rats that was identified by Charlotte Friend in 1956. The virus infects immunocompetent adult mice and is a well-established model for studying genetic resistance to infection by an immunosuppressive retrovirus. The Friend virus has been used for both immunotherapy and vaccines. It is a retrovirus which has single stranded RNA as its nucleic acid, instead of the more common double stranded DNA. Officially, its classification is: Group VI (ssRNA-RT), Family: Retroviridae, Genus: Gammaretrovirus, Species: Murine leukemia virus, which means it is from the same Group and Family as SIV, HIV-1, and HIV-2, but from a different Genus and Species. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friend_virus. A related article is “Immunity to retroviral infection: The Friend virus model” The most famous retrovirus is HIV-1.

4. Lab mice should have exercise wheels, a few simple toys, a little variety in the diet, to relieve stress and boredom. Research results can then be more reliable, because stressed, sedentary mice and other lab mammals have less healthy blood chemistry than unstressed, non-sedentary ones.

5. “Research, Inc..”

6. A rumor spread that I had been dismissed that final week from the program due to violating the housing regulations, but in fact I continued on in Dr. Moore’s lab and with Dr. Grace.

7. St. Francis had a fine premed and medical training program run by some outstanding medically trained nuns, some of whom also worked at local hospitals, while others did medical research. Still others cared for the sick in Africa.

8. One about the onset of melanoma (skin cancer), a second on the techniques of handling monkey viruses safely, and a third on developing a medium for “advanced tissue cultures.” (These were code words for “cancerous human cells.”)

9. I continued my relationship with Dr. Reyniers and his research (including using radiation) into cancer-causing viruses influenced me greatly. I also felt I had a little impact on him as well, as we discussed these subjects for hours at a time.

10. Because I’d been accepted at Purdue University, Dr. Diehl had begun to set up contacts for me there. Then came the conference at Dr. Moore’s home, where I persuaded Moore and Diehl to let me go to St. Francis for two years. Dr. Diehl then contacted Dr. Fuller — a new graduate from Purdue and highly recommended — asking him to facilitate matters for me at the hospital where he now held a high position.

11. I should point out that Eli Lilly was the first company to synthetically produce the psychoactive drug known as LSD.

12. I knew that the polio vaccine had been contaminated and that some people had been injected with it. At this time, I assumed that surely the rest of the contaminated vaccines had been removed from distribution after this “error” had occurred. That assumption proved to be incorrect, as I would later learn in New Orleans.

13. I had a latent fear about my poor vision and the predictions that it would get worse in time. If my vision problems worsened, I could no longer work with microscopes.

14. An unofficial group of scientists who vetted me for the National Science Foundation grants.

15. “HA” indicates that the melanoma under study was grown in the body of a hamster. However, the ID number of the melanoma being studied in the hamsters showed it was of human origin.

16. My parents removed me from St. Francis so quickly that the paper was left behind. But the abstract was published anyway, in anticipation that, of course, the paper to which it referred would soon be submitted. It never was. Further, when I entered the University of Florida, the threat that my parents might interfere meant that I did not dare ask to work with such precious materials again until I was permanently out of their reach.