— CHAPTER 11 —

THE PROJECT

Sunday, May 5, 1963

Awakening next morning, I lay half-dreaming in the pretty new bed at 1032 Marengo St., musing how events of the past week had turned everything upside-down. Though Lee Oswald had led me to The Mansion and its miserable outcome, he had also stepped forward and made up for it by finding this little cottage and paying a third of the rent. Surely the rush of affection I felt, just thinking of him, was due not only to his generosity, but also because I felt abandoned by Robert, who had not only hidden the news that he’d be living apart from me, but also had refused to tell me how to contact him. The scrap of paper that represented our marriage was just a birth control pill generator. As Lee had said, when I first met him: “Love — unto the death!” didn’t seem to apply to Robert A. Baker, III.

I got up and got dressed. Susie said a “housewarming gift” had arrived from somebody in Marcello’s family. It was a big loop of sausage and a medium-sized wheel of cheese — enough food for a week.

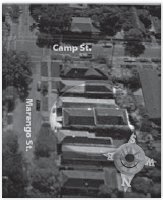

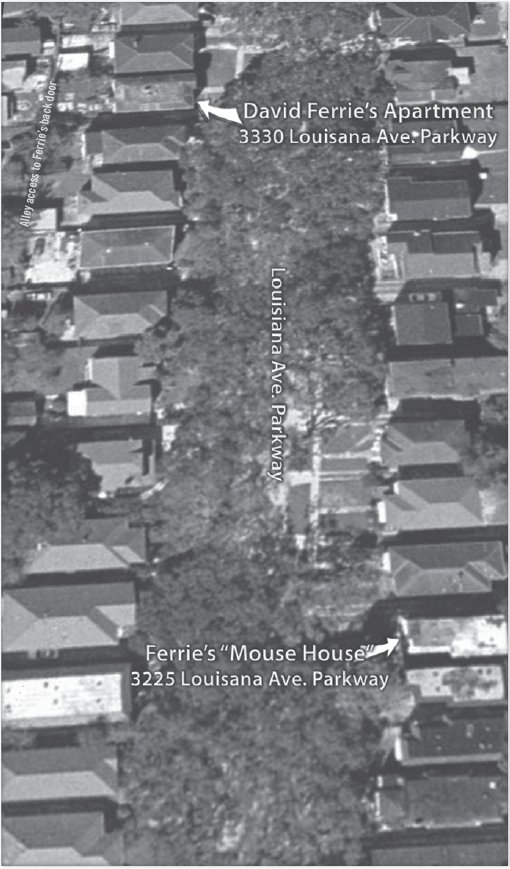

Before long, Lee arrived and escorted me to David Ferrie’s apartment. We caught the bus on Louisiana Avenue and quickly plunged into an impoverished black neighborhood. At the far end of Louisiana Avenue was Claiborne Avenue, where a branch split off to the left, becoming a smaller street named Louisiana Avenue Parkway.1 This is where David Ferrie lived. Its close proximity to a ghetto was rather alarming to me, but side-by-side opulence and squalor is one of the things that give New Orleans its unique personality.

Today, Lee and I met with Dave Ferrie to go over the “Project,” as he called it. Dave explained that the makeshift lab in his apartment was actually part of a sophisticated network of laboratories strung across uptown New Orleans, each with different equipment and performing a different function, but all united by a common goal: to develop a cancer weapon and kill Fidel Castro.

The configuration of these labs was basically a circular process which repeated itself over and over. With each lap around the loop of laboratories, the cancer-causing viruses would become more aggressive, and more deadly. Originally, these viruses came from monkeys, but they had been enhanced with radiation. The virus we were most concerned with was SV40, the infamous carcinogenic virus that had contaminated the polio vaccines of the 1950s. But the science of the day was not terribly precise, and cross-infection between species was common in the monkey labs. So it was impossible to know if we were working with SV40 only, or a collection of viruses.

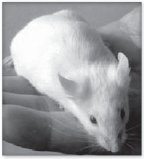

We assumed there were probably other viruses traveling with it, but whether it was SV40 or SV37 or SIV did not really matter to us. What mattered was whether it produced cancer quickly. For our project, these cancer-causing viruses had been transferred to mice because they were more economical than monkeys, and the viruses thrived just as easily, which is why mice are so widely used in medical research.

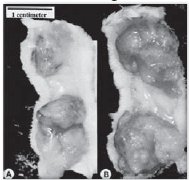

This loop included a large colony of thousands of mice kept in a house near Dave Ferrie’s apartment. I called it “the Mouse House.” People connected to the Project handled the daily care and feeding of the mice, and bred them to replace the population which was constantly being consumed. Several times each week, fifty or so live mice would be selected based upon the apparent size of their tumors. These mice had tumors so large that they were visible to the naked eye. They would be placed in a cardboard box and quietly brought through the back door of Dave’s house for processing. Once in Dave’s kitchen, we would kill the mice with ether and harvest their tumors. Harvesting meant cutting their bodies open and excising the largest tumors. The tumors were then weighed, and their weights recorded in a journal. The odor was terrible.

The largest of the harvested tumors — the most aggressive cancers — had a destiny. We first cut very thin slices from these tumors and examined them under a microscope. We had to be sure what kind of tumor we had, in each case. Bits of the “best” tumors were selected for individual treatment: each specimen was macerated, strained, mixed with RPMI medium, then poured into a carefully labeled test-tube. These were placed in Dave’s table centrifuge, and spun. Most cancer cells went to the bottom. The liquid on top was poured into a big flask, then more RPMI medium, with fetal calf serum, and sometimes other materials, was added to each test tube. These were the beginnings of tissue cultures, to be grown elsewhere. The test tubes were then placed in a rack in a warm, insulated box. The rest of the tumors, from which these cultures had been started, along with the liquids in the big flask, were poured into Dave’s cooled-down Waring blender (container was chilled in the refrigerator). The result was a “soup” you’d never want for dinner. Filtering the “soup” created a “cell-free” filtrate labeled to correspond to the tissue cultures and slides. The liquid, full of cancer causing viruses, was placed into a cooler with ice. The tissue cultures and the cell-free filtrate were now ready for the next lab. We called this “The Product.”

The next lab was in Dr. Sherman’s apartment, where she would examine the slides under a microscope. There, the world-famed oncologist and surgeon selected the most promising examples and took them to another lab on Prytania Street, where she used a more powerful microscope to examine the cells in exquisite detail.2 I never went to the Prytania Street lab myself, but I was told that it had an electron microscope.

Once Dr. Sherman had determined which samples showed the most promise, she would take them to yet another lab in uptown New Orleans, where the carcinogenic viruses would be exposed to high-voltage radiation, in hopes of mutating them. You can’t predict whether the genetic damage done to the virus will make it stronger or weaker, so it is an imprecise step. But once these newly enhanced viruses are allowed to “work,” the question answers itself. The stronger ones quickly become cancerous, and the weaker ones do not.

Our goal was to find aggressive cancers that produced fast-growing tumors. So these mutated monkey viruses were put into tissue cultures to establish themselves, and the most aggressive of these cancers were brought back to the Mouse House to be injected into newborn mice, whose immature immune system was incapable of fighting off the cancer. There, a new generation of tumors grew quickly. These mice remained in the Mouse House until their tumors were large enough to be harvested. Then batches of them were brought across the street to Dave’s apartment where “The Process” started all over again, making the cancers more aggressive with each generation. It was an endless loop. Precisely what these mutated monkey viruses had become after exposure to the radiation, nobody knew. All that mattered was whether they produced cancer. But the Project had gotten bogged down because the cancers were not transferring successfully back into primates. And if they did not work in primates, they probably wouldn’t work on humans, like Fidel Castro.

The other problem was that the new cancers were getting dangerous to handle, and somebody with specialized training had to take over at David Ferrie’s lab, for everybody’s safety. That’s where I came in. The training I had received at Roswell Park Cancer Institute, and the melanoma experiments I had quietly conducted for Dr. Ochsner at St. Francis and at UF, gave me the right credentials. My innocent teenage girl pose made me an ideal candidate for this secret cancer work.

Another part of the job was based on my speed-reading skills. I would read and digest cutting-edge cancer research, and pass the most promising ideas and methods on to Drs. Ochsner and Sherman with my comments. They would then decide which of my recommendations to implement. To get me started, Dave handed me a foot-high stack of papers, and more kept coming on a regular basis. Keeping up with the constant storm of material occupied many of my “idle hours.”

As I read these documents, I was not surprised to see that Ochsner’s friends, including Drs. Moore, Grace, Mirand, and others at Roswell Park, were working on related subjects. There were also papers from colleagues at Sloan-Kettering, M.D. Anderson, and the University of Chicago, as well as a few papers from Japan and Germany. Most of these articles were culled from conferences and journals, but some were unpublished.

Lee’s part in this effort was also important. Besides helping me get set up in an apartment and a cover job, he told me that he was with the anti-Castro Cuban community in part to determine which medical contacts could be trusted in Cuba.3 The plan was for Lee to infiltrate Cuba and deliver the bioweapon to friendly doctors. To that end, he needed to learn how to keep the tissues alive during transport to Mexico, and then on to Cuba.

Nothing about the Project, its people, methods, or materials was to be written down. So Lee would have to learn the medical jargon and techniques from me over the next few months, memorize the technical information needed to use the weapon, and transfer that information to others orally. In addition, he had to perform other duties for Guy Banister, as well as pretending to have a job, so he was quite busy most of the time.

Dave and I talked about my schedule. I would come to Dave’s apartment on Wednesdays, Thursdays and Fridays. As long as I left before Dave got home from work, I would not run into anybody. Mice would come and go, but since they were all identical (white with red eyes) who would notice that they were actually different batches? Dave said that he dreaded writing the reports, so I told him to bring it on, noting that I had nothing else to do at night.

“I don’t have a TV set,” I explained. “Not even a radio. Since Lee will be busy at night with his family, and Robert isn’t going to be around, I’m free to write reports.”

Tired from all he’d been going through the last few days, Lee had been sleeping on the couch while Dave briefed me on the Project. Just then Lee got up, yawned, and sat down at the table with Dave and me.

“No TV or radio, huh?” he said to me. “So, what would you like to do today? Besides make love to me?

“Gee, that’s a hard question!” I replied. “Why would I want to do anything else? How about horseback riding? It’s been a year.”

“I like horses, too,” Lee said. “Let’s do it.”

Dave told Lee where two different stables were located, noting they were fairly expensive.

“Well, then, we’ll only go riding one hour,” Lee told him. “After that, we’ll just play chess.” He got up and snatched a board from one of Dave’s cluttered shelves. “Do you have an extra set of chess pieces?” he asked, folding the board under his arm.

“I have Robert’s medieval chess set,” I offered.

Dave, who didn’t want us to leave, said “They ride the horses into the ground on the weekends. Why don’t you go in the middle of the week, when they won’t be tired?”

Reluctantly, we sat down again.

“Do you know why the queen is the major playing piece in chess?” Dave asked. “Why isn’t it the king, as one would expect?” These were the kind of intriguing questions Dave would throw at us, out of nowhere. He then went into a long explanation about the Indian and Persian origins of the game. Suddenly, he stopped short.

“Chess!” he said, looking at Lee “That’s the key! They’re using chess terms in our code names. As if we’re in a colossal chess game.”

Lee raised an eyebrow. “I have to think about that,” he said. “In Russia,” he commented, “my keys involved a queen, three cards, and an opera’s libretto.”

Lee said he had been required to memorize an entire opera by Tchaikovsky called The Queen of Spades (Pikova Dama in Russian), based on a short story by Pushkin. Lee liked the opera very much, but had grown indifferent after having to memorize it for contact purposes. I had never heard of it, so Lee promised to read the original Pushkin to me from a little gray book he had, to help me appreciate the libretto. I’ll never forget that little gray book; Lee read to me from it on several occasions.4

That evening, the last we would spend all night at Dave’s house, Lee and I sat, spellbound, as Ferrie’s encyclopedic knowledge once again captivated us.

After an hour or so of philosophical lecture, Dave showed us how to fetch his two young Cuban helpers by phone. They arrived within minutes, bringing in a new batch of mice. These boys were poor, and knew little English, but they were diligent and dedicated. Miguel and Carlos also did lab cleanup work, such as autoclaving, cleaning flasks, and incinerating mice. Usually only one came, but this first time, we met both. After caging the mice, Dave said, “Watch this demonstration of hypnosis.” He gestured toward the boys: within seconds, both collapsed onto the couch, in a trancelike state. Dave admitted he took advantage of them sexually when they were hypnotized, but also when they were not; they seemed to enjoy Dave’s company.

Under hypnosis, the older boy, Carlos, went immediately into a snoring sleep. Miguel was told to stand up, and I thought he was awake, but he obeyed Dave’s order to steal a dollar bill from my purse right in front of me. It was the last dollar I had, so I was anxious to get it back. Dave told Miguel I couldn’t see the dollar, and amazingly, the boy behaved as if this was true, denying he had taken a thing while waving the bill up and down.

“He’d walk right off a fifty-story building if I told him to,” Dave said. “But people resist bad suggestions unless they’re really brainwashed.”

After the boys left, I declared that weak minds might be hypnotized like that, but not strong ones. Dave laughed, saying it was easier to hypnotize smart people, because 70% of them would agree to turn off the more rational left side of the brain. The smarter and more creative the subject, he said, the greater the chance they’d allow their right brain to take control, making hypnosis easier.

Dave then asked permission to hypnotize us, with interesting results. Dave worked awhile with Lee, but was unable to get him to cooperate. Finally, in frustration, he commented, “Why don’t you trust me?”

Lee laughed, reminding Dave that perhaps he still had some deep inner fears of Dave, so he would always resist hypnosis from him. Dave said Lee’s imagination was deficient and that was the reason he wasn’t “going under.” I disagreed. I had read a science fiction story that Lee had been writing at my apartment, and it clearly displayed his creativity and imagination.

I then offered to allow Dave to hypnotize me. “Go ahead, Captain,” I told him, seating myself before him. “Have fun.”

What Dave didn’t know is that my sister Lynda and I had practiced hypnosis on each other for years. I knew the drill. For some minutes, Dave struggled to take me down. Once he thought I was under his control, he ordered me to do a few absurd tasks, such as to rub the top of my head. I complied.

“See?” Dave told Lee. “Women’s minds are more flexible, they are more receptive to suggestions, because they are more verbally oriented. Now watch this,” Dave said, “and don’t jump on me when I do it.”

“Be nice to her!” Lee said, uneasily, seeing that Dave had brought out a large hatpin.

“I only wish to demonstrate that, in this state, she can feel no pain,” Dave said. “J,” he said to me gently, “I am going to stick this needle into your arm, but you damned well will not feel it. Hold out your left arm, please.”

Oh, brother! I extended my left arm and Dave pushed the hatpin into my flesh like he was giving me an injection. Having been poked a thousand times during my long stay in the hospital, I had learned to tolerate the pain of needles. I didn’t move.

“See?” Dave said, triumphantly. “Why don’t they use this for childbirth? Think how this could help women. Do not move,” he told me. Taking up a Polaroid camera, Dave snapped a picture of the thing in my arm. But I’d had enough. As soon as he lowered the camera, I said, “I thought you weren’t going to use ‘damn’ in my presence anymore!” With that, I pulled out the hatpin and rubbed the sore spot on my arm, “Damn!” Dave repeated, oblivious to the irony of his comment. As Lee realized what I had done, he began to smile.

“Why be so violent?” I complained, finding some alcohol and cotton. “You didn’t even swab my arm first. I could get tetanus from that old needle.”

I explained that I not only had prior experience resisting hypnosis, I’d gone through months of round-the-clock intravenous feedings, penicillin shots, blood tests and spinal taps, so that I’d learned to ignore the pain of needles long ago. “But if you had tickled me with a feather, I wouldn’t have been able to keep a straight face,” I admitted.

Lee then recounted his own horrific hospital experience from his youth, when he endured an operation on the mastoid process — a part of the skull that juts down behind the ear. Infections in bone are extremely painful, and in the 1940s operations to cut away the infected bone resulted in agony for days. Such experiences stay with children, and help them understand suffering in a way others cannot.

Dave was defeated. His attempts to hypnotize us had failed. Trying to regain some of his former stature, Dave said he wanted to show us something special and brought out a black light. He invited us to follow him into the bathroom. He closed the door, turned off the overhead light, and switched on the ultraviolet lamp. There we saw the germs, mold, microscopic flora and fauna thriving in Dave’s filthy bathroom. All of it splashing to life in hideous color.

“I can get any hospital closed down for unsanitary conditions,” Dave said. “Just take a black light and go in with sanitation inspectors. They use the same bucket of dirty water over and over, and just spread the germs around.”

I was horrified to see rivers of yellow stains flowing in the toilet, with splotches of orange bacteria on the toilet seat. I immediately resolved never to sit on Dave’s toilet again. From then on, Lee and I avoided Dave’s bathroom as much as possible.

“You think this is bad?” Dave crowed. “You should see what’s on a public toilet seat. They think Howard Hughes is nuts because he takes Kleenex everywhere to handle doorknobs. But he knows what regular light won’t show you. He saw all this stuff with a black light.”

Dave continued to expound on the benefits of ultra-violet light, saying that it could kill anthrax, tuberculosis, even the black mold that stubbornly plagues ships and ‘sick’ houses. “People don’t know how to kill black mold, and some die from it,” he said. “But if they kill that stuff with acetone or mineral spirits, then they can use a black light every few weeks to finish off any new stuff that shows up. I use this lamp to kill whatever crud the mice are bringing in here,” he said. “I do have my housekeeping standards.” Lee and I looked at each other and smiled: we had never noticed any!

We returned to the table and Dave brought out a variety of things for us to view under the black light. He presented a horse tooth, fossils, seashells, and rock samples, like fluorite and uranium. Dave also brought out three rings: an aquamarine ring that he said belonged to his mother, a small ruby ring that glowed purple under the light, and one carved with an ugly mythological creature.

“This is my priestly ring,” he said. “I use it for black magic. And Satanic rituals.”

“Are you serious?” I said, taking up the exotic ring.

“Of course not,” Dave replied. “When I say a Mass, and sometimes I do say a Mass, it isn’t a Black Mass. I’m not a son of Satan, so I wouldn’t wear that thing. I love God. But I use things like this to penetrate religious cults. I can go into certain places around here with that ring on, and they think I’m one of them.”

Dave said he knew about every religion on earth and had witnessed the rites of Voodoo and Santeria.5 In fact, his interest in hypnotism came from observing religious oddities, like speaking in tongues, chanting, and rosary prayers, which had essentially the same result. They hypnotized the participants to make their minds more pliable. The drugs used in Voodoo were of particular interest to him. Eventually, Dave said, he was asked to participate in a study of hypnosis secretly conducted at Tulane by the CIA.

Dave said he made friends with some of the professors at Tulane by bringing in young test subjects they could experiment on, and that he even taught a couple of classes for Dr. Heath, who was working with the CIA on a secret program investigating mind control.

The CIA, Dave explained, was intrigued by the legends of zombies. Under the influence of drugs, these people became slaves without a will. “I became a consultant,” he said. “At first it was with Voodoo drugs. Later, it was hypnosis.”

Then Dave showed us a large, olive-colored metal container with a lock on it. As he opened the box, he said that if we ever heard he committed suicide, not to believe it, because he was a Catholic. When I told him I felt the same way, Lee remarked that the right to commit suicide should be an individual decision, but Ferrie snapped back and they began arguing about suicide.

“What’s in the box?” I asked.

After extracting a promise from us never to describe its contents while he lived, Dave showed us. There was his will, some letters, photos, religious cards and post cards.

At the bottom was a fat brown file wrapped with a black cord knotted in front. Dave opened this file. Inside, the pages were stamped TOP SECRET. Because of my position at the table, I could only see the pages upside down. They were held at the top with fold-over spindles going through two holes. All the pages were stamped and signed. These were MK-ULTRA files. With the files was a report, also stamped and signed, that Dave pointed to proudly. His name was not on the report - just a number.

“This is based on my dissertation about hypnosis and retinitis,” Dave confided. “What a crock! My ‘dissertation’ to get my ‘doctorate’ was a cover for my real work: logging responses of the size of the pupil in our hypnosis experiments.”

He added that the size of the pupil could tell a lot about what a person was really thinking, and would even indicate if they were really hypnotized. Dave said he had helped the CIA link pupil size-changes to truth-telling

“I shouldn’t have told you to close your eyes so much,” Dave said to me. “I should have looked at your pupil sizes, and checked their responses.”

“Why didn’t you do that, Dave?” Lee asked.

Dave shook his head. “I find myself avoiding looking directly into people’s eyes much anymore, ever since my hair started falling out.” Dave’s mood suddenly changed with this admission. He abruptly carried the box back to his room, and then got himself a beer. Despite the late hour, he had more to tell us about mind control and the experiments on people, frequently without their knowledge. Yes, American citizens were being used as guinea pigs by their own government.

“They tell people the program is shut down now,” Dave said, “but that’s not so. It just has a different name. These things never die. It’s an iron-clad law that it takes more energy to stop a government program than to start one. This one’s self-perpetuating.”6

I sat down at the piano and started to play, as the two men talked and drank beer. Lee had been down some mind-twisting avenues himself: he had been taught passive non-resistance techniques to avoid releasing information, and through severe, stressful training, had learned how to resist harsh interrogations. He was prepared for capture and torture when he entered Russia. Visions of what Tony Lopez-Fresquet had told me came before my eyes. I better understood what a big chance Lee took when he entered the Soviet Union. The Soviets were aware of the existence of a CIA training center at Atsugi, hidden in former Japanese bunkers. They would surely suspect Lee of being a spy. So how did he manage to survive?

When Dave went to the bathroom, Lee handed me his beer can. “See how much I drank!” he said, smiling. “I saw how you looked at me,” he went on. “You were thinking about your father. Beer doesn’t taste half bad, you know. But I rarely actually drink it. I gave the stuff up.”

The can was almost full. I would never have guessed!

Then Lee told me how he got himself thrown into the brig by pouring beer over a Marine sergeant’s head. He said the act was a necessary part of his cover to prove his “hatred” of the Marines.

Lee said he’d believed the odds of his leaving Russia alive were about 50/50. And, if he did make it out, his own boss might have him arrested. Lee said his name was “Jesus,” letting the irony speak for itself.7

“He’d wonder how I survived,” he told me. “Maybe wonder if I became a traitor.”

Lee said he had carefully planned everything, though, to prove he wasn’t a turncoat.

Lee and I were tired and wanted to leave. We both needed sleep before another challenging day, but Dave said he had one more piece of instruction to give us. David Lewis, he explained, had been recruited to help Lee. We should, therefore, cultivate a social friendship with David Lewis and his wife Anna, so they could meet without Jack Martin getting involved.

Lewis had agreed to this and would be paid for his services, provided Jack Martin was kept in the dark.8 David Lewis’ role was to get information about Cubans arriving on buses from Mexico and pass it on to Lee, so he could hunt down potential Pro-Castro infiltrators coming into the United States. For this reason, David’s temporary job handling luggage at the Trailways bus station was expanded.

“More Cuban refugees use Trailways than Greyhound to get here, because it’s the cheaper of the two bus lines,” Dave explained. “And infiltrators like to pose as just another poor refugee seeking asylum.”

Dave said the real refugees brought all the possessions they could cram in their suitcases. Those who came with half-empty suitcases probably intended to return to Cuba, bearing American goods that had become scarce since the near-total embargo imposed by Kennedy in 1962.

“Car parts, you name it,” Dave said. “That’s how they make money behind the blockade. Those guys are probably harmless, but some might be pro-Castro spies.”

David Lewis would get names from tags and tickets, and provide general descriptions of all Cubans he discovered with underweight baggage.

“By the way, Marcello will also be getting our information,” Dave said. “In some cases, Marcello will take care of some of these characters himself, for his good friend, Santo Trafficante.” Dave hastened to say that Marcello rarely killed these people. He preferred to ruin their reputations so they’d return to Cuba in disgrace. One method was to have a cooperative police officer plant drugs on the suspicious Cuban, arrest him for drug possession, jail him awhile, have him beaten up, and then deport him.

Dave said we would soon meet his illustrious friend, Mr. Lambert, who had worked with Dr. Ochsner for years on his Latin American dealings. Lambert would make use of the information that Ochsner secretly learned from Latin American leaders who sought his services as their emergency physician.

“There is no man in the United States with closer ties to both Latin American leaders and the CIA than Ochsner,” Dave said. “He’s the go-between, the doctor for all those big names the CIA wants to control. Dr. O’s a tough bird,” Dave added, “but he’s naïve as a kid about what he’s gotten himself into. Still, he’s feisty, always ready to pass information back and forth for the CIA.”

As for himself, Dave warned us clearly: “If anybody ever asks you if I have anything to do with anti-Castro matters anymore, the answer is always “No.” If anybody asks you if I have ever been associated with the CIA, the answer is always “No.” You can say I help out the FBI from time to time. That’s okay. But to my boys, and everybody else, I’m just a sex fiend, a drinking buddy, and a pilot. Let’s keep it that way. As far as my friends know, these mice are the same white mice, day in, day out, for some nutty project of my own.”

Dave said he would make concessions so that I would feel safe doing my work in his apartment. First, he said he wasn’t going to have any more parties for a couple of months, so we could get the project on a faster track. Secondly, his new room-mate would only be there on weekends, and when college classes ended, he would “go home to Mama.” And then Dave reminded me that if my husband ever showed up again, he should never know about my connection to Dave’s apartment. “Robert’s sure to return,” I said bitterly. “He’ll show up eventually, because he can’t go without his lovin’ too long.” Robert still had not written. I could have been dead and buried by now!

By now, I knew what Robert’s priorities would be after several weeks at sea. As his new wife and “lovey-dovey,” the sequence of events was all too predictable. “But this time,” I told Lee and Dave, “If he won’t let me have any rest, I’m going to dump a bag of ice cubes on the hottest part of his anatomy. Maybe then he’ll cool off enough so we can actually talk!” They both laughed.

When Lee took me home, it was shortly before dawn. Collie barked a few times as we arrived. Susie hushed her. When I realized that we had woken her up, I told Susie I was sorry. She explained that she had spent years rising at an ungodly hour and feeding her husband a solid breakfast before he went to work on the docks. We sat at the kitchen table as she served us a breakfast of ham, eggs, and fresh squeezed orange juice. Lee closed his eyes as he finished, leaning back and smiling happily. He was in heaven. Susie beamed. “I have no one to cook for anymore,” she said, adding that her children rarely came to her house since she had started renting out the front.

“I’m glad to rent to a girl,” she added. “The last two were men, and they didn’t pay me.”

“If this girl doesn’t pay, let me know,” Lee told her. “I’ll send a hitman over.”

“Very funny!” I replied. “I see you need another beating!”

“I see you’re never going to find out if Adam and Eve got away!” Lee replied, grinning. It was now morning, and we were exhausted.

“I wonder if Robert sent a letter,” I mumbled, so sleepy that Lee and Susie guided me to my bed, where I collapsed, too tired to undress.

“I’m leaving now,” I heard Lee tell Susie. “But I might be back. I’m going to try to intercept the mail at Mrs. Webber’s place around 10:00. If he wrote, it will ease her mind.”

“Why don’t you just stay, Lee?” Susie suggested. “You can sleep on my couch until it’s time to check the mail.” He admitted it would be good to sleep and headed for the couch.

I was drifting off. Almost asleep, I noticed that Susie was taking off my shoes. “Can I do the dishes for you? “ I offered in a dreamy voice.

“Goodness, no, child,” she answered. “Sleep now!”

“Do you know why we were out so late, Susie?” I asked her.

Susie paused. “I learned a long time ago not to ask what Bill had to do to get along with the people here in New Orleans,” she finally answered.

“This isn’t about Carlos Marcello and his people,” I told her. “Lee is a very brave man ... trying to help our country. He is working for our government... but because he is also connected to Marcello through his uncle Dutz, he can go places and find out things that regular agents can’t.”

“Oh! I hope you don’t get hurt!” Susie said.

“I’m not out there risking my neck like Lee is,” I mumbled. “I just do lab stuff. But I sure owe a lot to him, for finding this lovely place. And I owe a lot to you.” I gave Susie’s hand a squeeze and said, “Thanks for letting me stay here.”

“You can stay as long as you want,” Susie answered, leaning down and kissing me on my forehead. “Now go to sleep, honey,” she whispered. “I’ll wake Lee when it’s time.”

Monday, May 6, 1963

The next morning I heard a tap-tap-tap that was now becoming familiar. Lee was standing there with a big smile on his face, holding four flower pots full of begonias. I let him in.

“Good morning, Juduffki,” he said cheerily. “I decided you needed these.” He went to the window, which stared at a bleak wooden wall of the house next door.

“This will help brighten things up,” Lee said, putting the plants on the window sill. Then he stepped back to admire the pink and red blossoms.

“They’re beautiful, Lee.”

“I also brought you a radio,” he said, opening a sack and removing a little radio. After he showed me which stations played which types of music, I asked him if Robert had written.

“Go get ready,” he said, avoiding my question. “We have to go to the employment agency.”

I looked at the clock. It was almost ten. I quickly put on a red plaid dress and high heels. Lee said I looked nice, but advised me to take some casual clothes along, too.

“Did you see if Robert sent a letter? “ I asked again.

Lee said he had, but there was still nothing. I withered a little more inside.

As we boarded the Magazine Street Bus, I told Lee, “I don’t understand it. He wrote me every day the two weeks we were separated last summer.”

“He’s on a boat. Maybe the mail was delayed,” Lee said soothingly. “Let’s go sit in the back.”

“Why?” I asked.

“See all the Negroes? They are required to sit in the back of the bus,” Lee explained. “I don’t want to sit up front, when they can’t.”

Lee hadn’t mentioned this before, since the buses we had been on were almost empty, but the Magazine Street Bus always had a lot of riders, and from then on we made a point of going all the way to the back. In time people began to save us a seat. We had the satisfaction of making our own little statement in racially tense New Orleans.

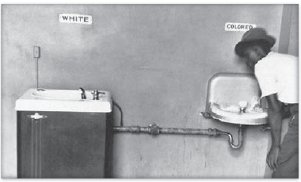

In 1963, there were still signs everywhere proclaiming ‘white’ and ‘colored’ for water fountains, parks, rest rooms, and so on. At the end of that year the signs finally came down. Though laws were on the books forbidding seating discrimination on the buses, the social reality still forced even a poor worn-out black cleaning lady to shuffle her weary way to the back. That was wrong. I soon felt as strongly about it as Lee.

We could not march with Martin Luther King, but we could do this much. And we did. I never hesitated to support Lee in all such gestures.

We arrived at the A-l Employment office shortly before noon and practiced typing.

“I have to pretend to seek work in order to get my unemployment checks from Texas,” Lee told me. “For example, I have to agree to go to interviews, but I rarely actually go.”

Lee said he needed the unemployment checks to account for his economic survival before his job started in New Orleans. He had to have some visible source of funds, or it might look suspicious.

“On Thursday, this will be over,” Lee said optimistically. He would go for a final “interview” at Reily’s, and then he would be hired. The outcome was a foregone conclusion, he explained. The process was really a sham. It just had to look real. Then he once again inquired if I would go to work at Reily’s with him.

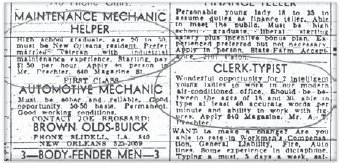

“I’m still in a quandary about it,” I told him “I’d like to talk to Dr. Ochsner first, but it looks like I’m being pushed in that direction whether I like it or not.” Lee then showed me the newspaper classified ad that he was responding to, as well as the ad for the job I could get.

“It says here they are looking for two clerk-typists. That’s not me,” I protested.

“That was before they heard about you,” Lee explained. He said he had called Mr. Reily this morning to find out how to fix that.

“Two weeks ago, Mr. Monaghan, the Vice President, lost his executive secretary,” Lee explained. “They decided it was safest to hire two part-time clerk-typists to take her place, because they didn’t have anybody they could trust except Monaghan to handle my cover.”

“But I’m a lousy typist,” I objected.

“The beauty of the job is you really don’t have to type much,” Lee explained. “They only decided to hire two clerk-typists so they wouldn’t catch on to me.”

“And I would supply you with protection, instead of this Mr. Monaghan?” I asked, without understanding the dimensions of the commitment.

“You’d help a lot, just by clocking me in and out,” he said. “So I won’t get fired for too many absences and late arrivals. I have to be there at least three months. As Monaghan’s secretary, you’d have access to the time cards. You could also help to reject the background security checks of anybody Personnel tries to hire to take my place, until it’s time for my termination.”

“You’ll be terminated?”

“I have to look like a failure,” Lee reminded me. “Why else would I hate America and want to go live in Cuba?” Lee said softly. “Besides, I can’t work on the training film if I’m still cleaning out roasters at Reily’s in mid-July”

“Cleaning out what?”

“Roasters. They roast coffee beans at Reily’s. At least, until their new factory opens. I’ll be doing all kinds of odd jobs, too,” Lee said. “Oil machinery, replace lights, help with packing. Whatever. But we’ll be together every day, if we both work there,” Lee added. “We’d ride to work together on the bus. We’d ride home together every night. For weeks.”

I admitted that was an inducement, but still felt my incompetence would show at once. I’d never get away with it.

“Ah, but this is no ordinary secretarial position,” Lee said. “Most afternoons you’ll be able to work at Dave’s lab and, because Monaghan is a former FBI man, it will all be safe.”

“An FBI man?”

“He’s been brought in to protect not only me, but a few others who also have cover jobs there,” Lee said. “He’s the first Vice President Reily Coffee’s ever had who wasn’t a Reily. It’s all part of INCA’s big push against Castro.”

“What’s INCA?” I asked.

“That’s The Information Council for the Americas,” Lee explained. “It’s Dr. Ochsner’s anti-Communist propaganda arm, used by the CIA.”

Lee told me that INCA taped anti-Communist and anti-Castro programs, shipping them to hundreds of Latin American radio stations on a regular basis. Ochsner and Dr. Sherman made trips to Latin America frequently, providing and gathering even more information, which was shuttled through INCA to the CIA. Originally, Lee hadn’t wanted to work for Reily, to give him time to be in the training film; but then he learned that the Reily brothers were major supporters of INCA, and INCA used Reily’s private offices for secret meetings with advisors linked to the CIA and FBI. When Lee learned that his hero, Herbert Philbrick, was coming to a meeting that summer at Reily’s as an advisor, he requested a position there in order to meet Philbrick. That meant getting more deeply involved in Ochsner’s get-Castro project. But Lee’s dream to meet the real legend behind the TV show I Led Three Lives could now come true.

After we finished our A-l typing tests and interviews, I followed Lee to another employment agency, getting a good look at Reily’s modern, air-conditioned building at 640 Magazine Street on the way. Lee pointed out that Reily’s was convenient to Banister’s office, just a block and a half away around the corner. After phone calls to Monaghan, Dave Ferrie, and Dr. Sherman, Lee sat down with me at Mancuso’s, a coffee shop located in Banister’s building, and told me what he’d found out. First, Ochsner confirmed that he would interview both of us on Wednesday.

“He hopes you’ll agree to work at Reily’s,” Lee told me. “He said you’ll need to go to the library to learn how to read Standard & Poor’s credit rating books, and so on, but not to worry, you’ll still be doing your lab work.”

There would be errands, visits to the courthouse, background reports to analyze, credit risks to check on, and paychecks with problems to be issued on time.

“Is that all?” I asked sarcastically, feeling overwhelmed.

“That’s all I remember,” Lee said.

“When in heaven’s name will I have time to be in a lab?” I asked.

“You’ll always clock in at Reily’s,” Lee said, “and you’ll clock out there, too. But you’ll be doing lab work three afternoons a week. Monaghan will cover for you.”

The word from Ochsner was that if I didn’t want to do this, I could still enter an internship with Dr. Mary, right at the Clinic, living rent-free in Brent House. Otherwise, Robert’s earnings would have to cover an apartment in town, and transportation costs. He would hate that, of course, but if I accepted the internship and moved over to Brent House on Ochsner’s campus, we would not be living together at all.

“I guess Robert and I can always go back to making love in his Ford,” I said.

“He’ll have to live at the YMCA when he comes to town,” Lee said.

“It’s no life for a married man. I know from experience.”

“He has it coming to him!” I said. “And if he says, ‘Let’s pack up and go back to Gainesville,’ I’ll say ‘Guess what? I’ve got a scholarship to medical school, and I’m staying. It’ll be your turn to wait for letters.’”

Lee saw how bitter I was. “Maybe you should get your marriage annulled,” he suggested.

“Maybe I will,” I replied.

_______________________________

1. Claiborne Avenue was named after Gov. John Claiborne, the first governor of Louisiana. Generations later, the Claiborne family remained active in Louisiana politics. Lindy Claiborne married U.S. Congressman Hale Boggs who became Majority Whip of the House and sat on LBJ’s “Warren Commission.” After Hale Boggs died in a plane crash in Alaska, his wife Lindy took his place in Congress. After she retired from the House, she was appointed the U.S. Ambassador to the Vatican. Hale and Lindy Boggs had a daughter named Cokie, who became a CBS Correspondent in Italy, before becoming a political news analyst on National Public Radio. Today she is better known by her married name, Cokie Roberts.

2. The original location of Ochsner’s clinic was on Prytania Street. I don’t know for sure if that is where this lab was housed, but if there is an official investigation into this subject, it could be worth looking into.

3. Ochsner had a solid list of trusted Cuban medical contacts, as he and his staff had trained doctors from Cuba for decades, and many of them were furious with Castro’s decision to have all future doctors trained in the Soviet Union, which cut them and their protégés off from a long and illustrious association with Ochsner’s Clinic.

4. Veteran researcher Mary Ferrell was astonished when I told her, in the presence of witnesses, about the book. She was unable to conceal her amazement, stating that the unique gray book I described to her — of an unusual size, with floppy gray covers, and printed in Russian — was the only one of its kind that she had ever seen. She knew that it had belonged to Lee Oswald in 1963, because on a New Year’s evening in the 1970s, Ruth Paine had brought it out to show her and Ferrell’s husband, Buck. The gray book was a treasure the police hadn’t confiscated when they searched the Paines’ house looking for Lee’s possessions.

5. Santeria is a religion of African origin which is practiced in the Caribbean islands. Basically, it involves humans working with spirits. While it has some similarities to voodoo, the difference is that voodoo is much more involved with drugs and poisons.

6. Researcher Greg Parker helps confirm Dave’s remarks with records such as this: “To quote from extant MK-ULTRA documents, “The security considerations applying to xxxxxxxx were found to be significantly different from those governing manipulation of human behavior, a) Many xxxxx external projects in support of the xxxxxxxxxxx are being funded and managed securely outside the MK-ULTRA mechanism. “(July 26, 1963 memo from JS Eaman, Inspector General, Director, CIA).” (Internet Post #133 05-28-2004)

7. One of Lee’s CIA handlers when he went to the USSR was James Jesus Angleton, the famous spymaster who planned the CIA’s most complex missions. His telltale quote is worth considering: “It is inconceivable that a secret intelligence arm of the government has to comply with all the overt orders of the government.”

8. We used “Sam Spade” as a code name for David Lewis that summer. I did not use it in the narrative to avoid confusing the reader.