— CHAPTER 13 —

CHARITY

Tuesday, May 7, 1963

This was the day we were finally supposed to meet with Dr. Ochsner. “Don’t pretty up for Ochsner,” he’d said. “We’ll be seeing him at Charity Hospital.”

That was where the poor went to get free medical treatment. Lee suggested that I dress down and wear comfortable clothes, so I wouldn’t look out of place.

As I changed clothes, to pass the time, Lee looked at my portfolio of drawings and short stories. While I brushed my hair, Lee finished reading my story, “Hospital Zone.”

“This is good,” he said, adding softly, “I want to be a writer.”

“I think you’d be a good one, too,” I told him. “All my science talk derailed Robert from being a writer, to geology,” I mourned. “Now he’s out on a quarterboat somewhere.”

“Well, you’re influencing me to be a writer,” Lee rejoined, “so now, it’s even.” Lee called Dr. Ochsner’s office to pin down exactly when we were to meet him at Charity Hospital. He was told Ochsner had finished surgery, had finished making his rounds, and was meeting with staff before a quick lunch. Then he’d leave his hospital to drive over to Charity. He should arrive by 2:30 P.M. We might have to wait an hour after that, because Ochsner donated his time at Charity, offering his services free of charge to the desperately poor. Some of the more interesting cases would receive free care at Ochsner’s Clinic.

I was impressed. Ochsner got more done in a single day than most people could in a week. I later learned he also flew to Washington almost weekly, working on his research papers or reading medical journals en route. Duties in Washington finished, he’d fly back the same night, sleeping on the plane and arriving ready to conduct surgery at sunrise. That same week might find him in Venezuela, or at a medical conference in California. Or perhaps he would take off a day or two to play cards, or to hunt at a ranch with his Oil Baron buddies in Texas, raising funds for the Clinic. Ochsner also attended meetings for INCA, the Trade Mart, and International House (he was its CEO!), but he’d be operating on people every morning, or thundering imperatives into the ears of terrified medical students. He visited recovering patients with his staff. On some weekends, Ochsner took his turn at night duty for emergency operations — the same as any other surgeon on his staff. My admiration for Ochsner was boundless.

We then began to discuss how to find a way to account for Sparky’s fifty-dollar donation. As I started to tell Lee that Robert had still not contacted me after all this time, I suddenly felt overwhelmed and burst into tears. Lee soon learned that I was crying myself to sleep every night over that man. He then made a few calls on Susie’s phone, after which we took the Magazine bus downtown. A few more blocks of walking, and we were in front of a modest storefront, where numerous souvenirs, piñatas, Mardi Gras masks and other oddities were on display in the cluttered windows. This was 545 South Rampart Street. If you turned your back to the windows, and looked carefully, you could spot Reily Coffee Company way down to the right, on Magazine Street. A large sign overhead said “Rev. James Novelty Shop.” A smaller sign read: “Novelty and Religious items.”

Reverend James’ Novelty Shop, known locally as Rev. Jim’s, was both a souvenir shop and a gateway to a storehouse of the grotesque and beautiful, where shiny alligators ten feet tall, lifesize carousel horses, and colorfully painted dragons, devils, and dinosaurs were created for Mardi Gras floats, carnivals, and shop windows. There was a long table in the store, where people were busy lettering souvenirs with the words “New Orleans.” The shelves and counters overflowed with rubber masks, wigs, African drums, Indian headdresses, costumes full of sequins, costume jewelry, and feathers. One section was stacked with bibles, framed religious poems, and statues of the Good Shepherd.

This was the retail end of an unusual industry — a charitable enterprise creating work for poor artists, musicians and transients who needed to make a little honest money to get by. The lady in charge was a member of Reverend Jim’s church, and she was an artist. She welcomed Lee and showed us around. Behind Reverend Jim’s and the building next door was the warehouse where Mardi Gras floats were stored. Its cement floors were littered with sawdust and fluffy lumps of papier-mâché, with molds of all kinds.

There was a separate room full of critters ready to paint. We filled out papers testifying to financial need, read a Bible tract, and signed a promise to stay sober and drug free. We could work up to four hours a day at minimum wage, if our work was neat and satisfactory.

We started painting “New Orleans” over and over, on ceramic alligators, maracas, and salt & pepper-shaker sets. But soon, Lee was taken from the table. He had painted, in a very neat hand, “Wen Orleans” on several pieces.1 I asked to go with him when he was sent, with paint and brushes, to the papier-mâché warehouse to add colorful eyes and rosy mouths to some trolls. Altogether, Lee and I spent three hours painting trolls, dwarves and carousel horses. Then, realizing we could be late for Charity Hospital, we claimed our reward: five dollars and change!

“I told you to trust me!” Lee said, as we emerged, blinking, from the land of wombats and wizards into the bright sunlight of a busy city. But he immediately stopped in front of an African-American newspaper office nearby. “I have to talk to somebody here,” he said. “But you go on. Just head toward Reily’s,” he said, turning me in that direction. A few minutes later, Lee caught up with me.

“I have to go to Banister’s right away,” he said. “But I called about Ochsner again. We’ve got an hour before we have to show up at Charity. The doctor’s running late.”

I wondered who had the busier schedule — Lee Oswald or Alton Ochsner! Soon we reached Banister’s building. I sat on the steps of the Camp Street entrance while Lee walked around the corner and entered through the Lafayette Street entrance. The doors were all propped open to catch the breeze, so from where I sat I could see into Mancuso’s Restaurant, where David Lewis and Jack Martin were sitting drinking coffee. As they were about to leave, David Lewis spotted me and came over. He invited me and Lee to meet his wife at Thompson’s Restaurant, which was around the corner. He said that he was grateful for the Trailways work arranged for him, and needed to discuss some of the details with Lee. As he left, I told Lewis that I would give Lee the message. While I continued to wait, I saw several Cubans walking toward Banister’s office. A few minutes later, David Ferrie hurried past. I called out to him and he gave me a quick wave.

“I’m late!” he shouted. “Talk to you later!”

After fifteen minutes Lee appeared, and we boarded the street-car and headed uptown. “Is this the way to Charity Hospital?” I asked.

“No,” said Lee. “Our meeting with Ochsner has been called off for today. He’s in emergency surgery. We’ll have to see him tomorrow.” We were now on our way to Palmer Park, a pleasant, quiet place where we could play chess, unobserved. Nearly across the street was an eatery called Lee’s Coffee Shop. He wanted us to eat there, because it said ‘Lee.’ His ultimate goal, just for fun, was to take me every place named ‘Lee’ in New Orleans. We played chess for over an hour, without resolution to the game, so Lee folded the board after memorizing the setup, and we went to get something to eat.

While we waited for our food, I gave Lee the message from David Lewis, which he said was good news. He called Thompson’s restaurant to arrange our date with David. Lee’s Coffee Shop served a mixture of good Chinese and American food: we eventually ate there a dozen times.

Wednesday, May 8, 1963

Lee had been invited over for breakfast, and I invited Susie to join us. I made palacsinta: Hungarian crêpes, the way my grandmother taught me.2 We ended up discussing the Hungarian Revolution, and I learned that Lee, too, had listened on short-wave radio to the pleas of the Hungarian rebels as they begged for America to come to their aid. Lee had admired the courage of the Hungarians ever since.

He asked many questions about Hungarian culture before we moved to my living-room couch to finish the chess game. Lee won: I had forgotten my strategy, but it was clear that he had not. At about 10 A.M., the mail arrived. As Collie tore after the postman, Susie brought me a letter. Robert had written, after five long days. It touchingly revealed that he didn’t care what my Catholic parents might think about our elopement:

“...we’ll have to live with each other, not with them, so let’s tend to ourselves, our own happiness. If they wanted us, it would be different. I knew who my mother-in-law and father-in-law would be before I married you, so let me take the responsibility for it.”

This manliness on Robert’s part warmed the cockles of my heart. Feelings of love swelled in my soul. But his next words reminded me how very much I was on my own:

“I hope you haven’t given up writing stories. Coarse as it may seem, take advantage of my absence. I’ll be back as sure as the sun will rise. Meanwhile you have a life to live without me, a secondary life, but a life not dead. There are three of us now, you, me and Us. It’s too late to write anymore now. The mail boat leaves early in the morning. I love you, I love you, I love you. Robert”

So, a letter took just one day to reach me, once the mail boat picked it up.

“I feel so guilty,” I told Lee, in Susie’s presence. “Is it possible to be in love with two men at the same time?”

Susie and I had discussed everything Lee had done for me, along with his miserable marriage, and the insensitive conduct of my brand new husband. Now she spoke up.

“Follow your heart,” she told me. “In your heart, you already know the answers to all your questions, honey.”

I looked at Lee helplessly. His wife would be arriving in a few days. And Robert would return “as sure as the sun will rise.” I had married him both for love and to get birth control pills. And though we were newlyweds, he left me alone for weeks at a time. I thought, “If that’s how he treats me now, how will he treat me after the novelty has worn off?” Lee observed that the date showed Robert wrote the letter before he knew I’d moved, but the address on the envelope was my new one.3 He hadn’t mentioned anything about it.

“It would have been nice if he asked ‘what happened?’ or ‘Are you okay?’” Lee said. Susie then pointed out other peculiarities, which I hadn’t noticed.

“He didn’t ask for your phone number, and he didn’t say when he’d be back.”

Astonished, I searched through the letter. It began, “My darling Judy,” and then began describing the quarterboat, what the work routine was, and the situation with my parents. Susie was right. There was still no mention of how to reach him in an emergency, and not a word about when he might be back; just the admonition that I must get along without him. Still, I defended him, since he’d finally written!

“Good Lord, girl,” Susie said, “You were only married three days when he wrote this. You’re supposed to be his sweetheart.”

“He is adjusting himself to his new surroundings,” Lee offered.

“Poppycock!” Susie said, taking back the letter. “If he had time to write the new address on the envelope, he had time to ask questions.”

“He’ll ask, soon enough,” I predicted.

“Sure, he will,” Susie said, “when he wants to get back between the covers with you. As for me, I hope he stays out there all year. I don’t want to meet him.”

“Neither do I,” said Lee.

“Darn!” I told him, “and here I was going to use you to make him jealous!”

“I’m afraid I would punch him in the nose,” Lee said.

“Well, so much for all of us being buddies,” I said. “Scratch that one.”

Lee said he had more work to do for Banister, and left. I went into my room and starting reading research papers in preparation for my meeting with Dr. Ochsner. As I read, I thought about the people in my world. So much had happened in the five days Robert had been gone! And how many days would it be before he returned? Who knew what would happen next? As I pondered Susie’s comments about Robert’s letter, I decided not to volunteer any information about how I was feeling, or how I spent my time. If Robert wanted to know, he should ask. If he cared about me, he would. Until then, I knew I couldn’t count on him.

The other people in my life didn’t look much better. Dr. Sherman had not bothered to contact me since that awkward incident at Dave’s party. And Dr. Ochsner was only now making time to see me. How could I count on them? Dave Ferrie was friendly, but without Lee at my side, I couldn’t trust him either. Susie was elderly, and I didn’t want to load her down with my problems. The only person in the whole equation that I felt I could trust with everything was Lee. Loyal. Steady. Reliable. He had never let me down. Deep inside, I felt he never would.

As I thought about Lee, I realized how close we had become. Too close to be just friends. I thought about the way he kissed me in the car after he rescued me from that knife-wielding sailor. Lee probably could have seduced me that night. We both knew that. But he didn’t. If I wasn’t married, we might have already become lovers. But I was not going to let that happen simply because he saved me from a mugger. Nor would it be because he found me a place to live when I had nowhere else to go. I had to know that I had his respect. Anything based upon my desperate situation, or upon Lee coming to my rescue, would be a false foundation for love, a shallow romance. Lee didn’t want us to become lovers on such a basis either. In fact, he had not even kissed me since that delicious night in Marcello’s car. If we became lovers, it would have to come from a position of mutual respect, based on strength. We both felt that way.

Wednesday, May 8, 1963

We got on the Magazine bus heading downtown to Canal Street. From there, we would transfer to another bus to reach Charity Hospital for our appointment with Dr. Ochsner. As usual, in our effort to make a silent statement supporting the rights of blacks to sit in the front of the bus, or wherever they liked, we moved to the back bench of the bus and sat amongst the black passengers. I had my research papers in a big canvas bag on my lap. In the back corner seat of the bus sat a heavy-set black woman wearing a cotton dress that hung on her large frame like a flour sack. Her eyes were closed, and she swayed from side to side as the bus lumbered along. Her arms were wrapped around a paper bag on her lap. We noticed a heavy odor around her. The other passengers noticed it too, and quietly moved away from her.

Then Lee nudged me with his elbow and used his eyes to point to the woman’s feet. Blood was dripping down her legs and pooling around her shoes. Lee was sitting just one seat away from her, and tapped her on the arm. She opened her weary eyes and looked painfully at Lee. Her face glistened with sweat and her mouth was locked in a sad frown.

“Ma’am,” Lee said. “We’re on our way to a hospital. We would be happy to help you see a doctor there.”

The woman shook her head solemnly and looked away without answering. I wondered if it was because Lee was a white man, and she was embarrassed about the blood. Perhaps she was on her way to see a doctor and would be getting off the bus soon, so we waited, saying nothing. She turned her head to the wall and leaned against the side of the bus, still holding onto the thick paper bag. “What’s in the bag?” I wondered. She rode all the way to Canal Street, the end of the line, and people filed out the back door. The woman slowly forced herself to her feet and made her way to the back door, leaving a trail of blood as she went. Lee signaled for me to follow him, as he stayed close behind her.

As she stepped off the bus and onto the sidewalk, her blood-soaked shoe slipped, and down she went, on her hands and knees, dropping the bag as she fell. The dark bottom of the paper bag ripped open, and a small stillborn baby and placenta spilled from the sack. Somebody screamed at the sight.

Lee immediately sprang into action, hailing a cab. As I knelt down to help the woman, she desperately tried to scoop the dead baby back into the torn sack. “Billy! Billy!” she cried. Between the sobs, she mumbled that her husband was a sailor who was out to sea, and her mother and sister were at work, so she was all alone. She’d called a doctor, and he told her to bring the dead baby and placenta to the hospital, but she had forgotten how to get there. “Oh, Billy!”

“We’re taking you to Charity Hospital,” I told her. Blood was now all over the sidewalk. When the driver saw all the blood, he didn’t want to let the woman in his taxi. Lee told the driver bluntly that if he did not help she would die. Before the cabbie could offer any more resistance, I quickly spread my research papers out to cover the seat of the taxi and sat her down on them. At this point, he had no choice. Fortunately, the hospital was not far. Soon, we reached the emergency entrance.

Lee helped the weak and wobbly woman get out of the car, as the cabbie grabbed a wheelchair. I transferred the blood-soaked paper bag (and the dead baby) into my canvas bag. Lee and the cabbie maneuvered the woman into the wheelchair and placed the canvas bag on her lap. The ER staff came out promptly, and Lee told them she had lost her baby. Without another word, the medical staff whisked the woman inside. I retrieved my bloody research papers from the back of the taxi and threw them in the trash. Lee said “What do we owe you?” to the cabbie. By now he realized there was a dead baby in the bag, so he refused to accept any money for his services.

Lee and I looked at each other blankly. Our emotions were drained. Both of us had blood on our hands and arms: we needed to wash up before meeting Dr. Ochsner. As we entered the hospital, the medical staff took one look at us and assumed that we had been fighting, so we had to calm them down and explained that we had just helped an injured woman get to the emergency room. We then cleaned ourselves up as best we could in the disappointingly dirty rest rooms. When we were done, we went to the registration desk and said we were there to see Dr. Ochsner.

Then Lee told me we couldn’t sit together because it might be remembered. The good news was that we would not have to wait long. Lee said that he would see Dr. Ochsner first by himself, then after a few other patients, I would follow, so nobody in the waiting room would connect us. It was easy to see that Charity Hospital’s clinic was overwhelmed by an avalanche of the poor, mostly blacks and latinos, in need of medical service. Lee’s precautions seemed ridiculous. But, I resolved to play it his way. Okay, we’ll play James Bond, I thought to myself, as I sat down on the wooden bench alone. I soon realized there were no white couples in the room. There were few whites at all. Lee was right, we’d have stood out like ticks on a dog’s ear.

Charity Hospital had been a bold move into public health in the 1930s. It was the brainchild of populist Governor Huey Long, and the 1,700 bed hospital was the state-of-the-art facility in its day, providing Louisiana’s poor with free health care for the first time. The gleam of the old polished wood and the faded overhead lamps gave me a glimpse of its previous glory days, but now the floors were dirty, and the waiting was endless. After half an hour, someone came out to get Lee and escorted him down the hall. He was gone about forty-five minutes. After he came out, he stopped to drink at the water fountain and then seated himself where I could see him. Fifteen minutes later, a nurse came out and asked me to follow her. She led me to a small conference room with a frosted glass door with no name on it. Inside sat Dr. Alton Ochsner, Sr.

“Won’t you sit down, Miss Vary?” Dr. Ochsner said politely.

Distinguished, mustachioed, and self-confident, power shot from this man’s eyes like little electrical charges. It was like being seated before an emperor. Nobody sassed Ochsner. Nobody stood in his way. He commanded everything around him in a relaxed manner that indicated he knew there would be no resistance to anything he ordered.

“Have you caught up with the literature?” he asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“We’re having reports flown in from both coasts even before they’re published. Every new strain of lymphoma in the country can be in our hands within days. Breeder mice are being ordered from different sources to avoid suspicion. If you need anything, let me know.”

I noticed that Dr. Ochsner avoided mentioning anything about my working in Dr. Sherman’s lab. Was Dr. Ochsner ordering me to run Dave Ferrie’s clandestine lab without even discussing the matter with me?

“My internship...?” I queried gently.

“Of course you’re going to Tulane in the fall,” Ochsner said. “I wouldn’t have asked you to come to New Orleans otherwise.”

“Will I still be working with Dr. Sherman?” I asked.

“You’ll see her every week,” Ochsner told me. “She’ll go over your reports. She’ll take you into her lab from time to time, to teach you procedures we’ll want you to know by September. But you can help us if you accept an assignment at Mr. Reily’s coffee company.”

“How would my talents be useful at a coffee company?” I asked.

“Your presence there will cut out two girls who could present problems for Mr. Monaghan,” Ochsner explained. “He has to have someone there every morning, and he needs you to cover for Mr. Oswald’s absences.”

Ochsner then explained that Lee would also be working on the Project by transporting chemicals, equipment and specimens to several locations. Nobody would suspect that Lee had anything to do with a project involving cancer research, he pointed out. Ochsner said Lee’s offer to work at Reily and to courier materials had already been accepted, but that he would also be involved in another aspect of the project, slated for later in the year.

My position at Reily would be salaried, so that my time out of the office would not be recorded and Reily would, in effect, be paying for my hours spent on cancer work. The same was true for Lee’s position.

This arrangement meant that I would receive more money than the stipend he had originally planned for me, Ochsner explained, and I would be able to live comfortably. Mr. Monaghan would see to it that I received a week of training at Reily, so I shouldn’t be afraid to tackle the tasks involved.

“I want you to remember that Mr. Oswald will be there to help you,” he stressed. “Mr. Oswald will have additional duties unrelated to his job at Reily’s, just as you will, but you can commandeer his courier services any time you need them during his work day.”

I pointed out to Dr. Ochsner that he was not giving me a choice about working in Dr. Sherman’s lab or at Reily.

“You managed, once again, to get yourself into some trouble,” he said firmly, “by somehow nosing yourself into the wrong side of this project.”

Ochsner looked sternly at me for a moment, but then gently added, “I will overlook it, however, since I didn’t know your schedule had changed, and I wasn’t available to direct your course.”

“I also got married,” I blurted out, before adding “You’d find out soon enough, anyway.”

“Do you need birth control pills?” he asked as if he had already guessed my motive. I was very relieved that he wasn’t angry.

“Yes,” I said simply.

“As far as your husband knows, you’re only a secretary at Reily”

“I doubt he’ll know where I’m working,” I said. “He’ll be out of town a lot.”

“Write nothing about cancer research on any forms you fill out at Reily.”

“How can I justify being hired, without any prior experience in the field?” I asked. “I flunked my typing test at A-l Employment.”

“Make up something,” he told me.

“No, I won’t do that,” I answered, stubbornly.

“Damn it!” Ochsner complained. “Have you no prior office experience whatsoever?”

“Well, my dad had me running his business for him for a few months, after he fired his accountant. I did bookkeeping and answered the phone. He did the typing.”

“Write that down,” Ochsner said. “Don’t mention you can’t type. Do you have any idea what creative lying is?”

“Mr. Oswald is certainly good at it,” I said. “But I won’t do it.”

“Foolishness!” Ochsner huffed. “On the other hand, I suppose I can take everything you say and write as plain and straightforward fact, then?”

“You can be certain of it,” I answered.

“Well, that’s worth something.”

“To understand the project, I need to read the prior reports,” I told him.

“They’re destroyed immediately after statistics are pulled from them,” Ochsner replied. “However, Dr. Sherman keeps a log. Talk to her about that.”

Ochsner grabbed a notepad from the desk and wrote a prescription for birth control pills, telling me to take the prescription to the hospital’s pharmacy. He also gave me a voucher for enough free pills to last the rest of the year.

“Take vitamin C daily and an aspirin every other day with those things,” he warned me. “The high hormone doses in those pills can cause blood clots. I don’t want to lose you due to a blood clot.”

“All right, I’ll do that, Dr. Ochsner,” I told him. “But I still don’t understand why you want me in Dave Ferrie’s lab. I think I could do more for the project in a real lab. The set-up at Ferrie’s has some problems.”

“That’s precisely why I need you to be in charge of Ferrie’s part of the project,” Ochsner said. “You know how to work under primitive conditions. In addition, besides your capacity to run it without supervision, you’re the fastest reader I’ve ever seen, and we need some ideas. You’re an unconventional thinker. I want your input. We’ve reached an impasse, and we need your serendipity.”

With that, Ochsner handed me a briefcase filled with a thick stack of research articles.

“What’s the problem?” I asked.

“Cross-species transfer,” Ochsner said. “And there’s another problem. We can inject a mouse with half-a-million cancer cells, but ten minutes later, the mouse has sifted all the cells out of its circulatory system. Only if we inject the mouse with over a million cells, do we get cell survival. If we injected a human with a dose of cells on the same scale, he’d have to take a pint of injections.” Ochsner then dropped the magic words. “Nobody could get away with injecting Fidel Castro with a pint of anything.”

With that, Ochsner concluded our meeting, and I left. Back in the waiting room, Lee was nowhere to be seen. I surmised he might be in the bathroom and waited a bit. Soon a nurse came over to me and told me Mr. Oswald was waiting outside the building. When I found him, Lee and I started comparing notes on Ochsner as we walked to Canal Street. Lee said that he had been questioned closely as to his right-wing sympathies, but knowing Ochsner’s leanings, had offered some of his creative lies by praising Banister’s work in ferreting out radical students.

“I also told him, and this part is true, that I wished to mimic Herbert Philbrick’s ideas about pamphleteering,” Lee said. “I brought up Philbrick, of course, in the hope that Ochsner would allow me to meet him when he comes to Reily’s for the INCA meeting.”

“Did it work?” I asked.

“I think so,” Lee replied. “I told him I was willing to do curbside leafleting to smoke out pro-Castroites here in New Orleans, and that both Banister and Dave thought this would be fine, after the students leave for the summer. I also showed Ochsner the newspaper article about Phillips, who was beaten by three men, and suggested since INCA had media connections that the more publicity my leafleting activities generate the more easily I can get into Cuba, if necessary.”

“Did he agree?”

“He’s going to think about it. I also volunteered to take the serum to Cuba, if they can’t find anybody else. I’m a radar man. Nobody would ever suspect I had anything to do with a biological weapon.”

We walked in silence for a few minutes, while I ruminated on the courage contained in these statements. If Lee was caught inside Cuba, and the nature of the materials were discovered, he’d be tortured and executed.

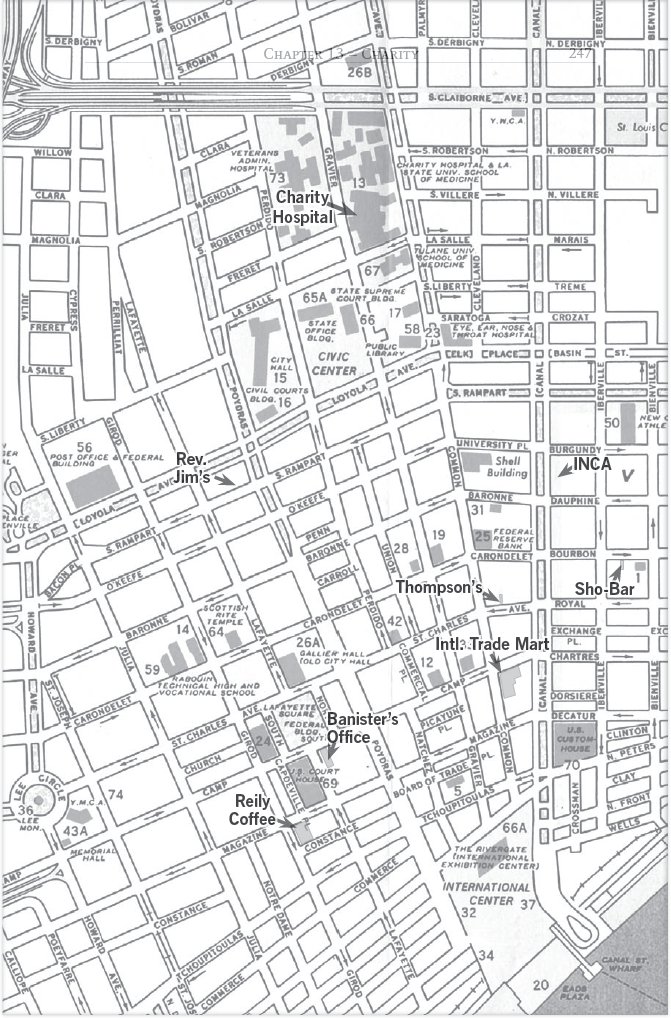

“We need to turn this day around. Let’s go see Lee Circle, and then pick up a few more dollars at Rev. Jim’s so we can eat Chinese tonight,” he said, taking charge of my briefcase.

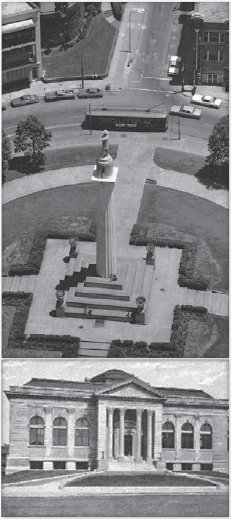

We had gone around Lee Circle a number of times on the streetcar, but this time we walked around the park to see the sights. Lee pointed out the statue of Robert E. Lee and proudly reminded me that he was named after the famous Confederate general. Then he pointed to an unremarkable new building and explained how it sat on the site of the old Carnegie Library, a spectacular building graced with Greek columns and magnificent appointments. Lee said this library had been one of his favorite haunts as a teenager.

“They tore down a beautiful building, constructed to last for centuries, “ Lee said angrily, “in a crooked money-making deal.” Lee added that other historic buildings were also being torn down all along St. Charles Avenue so that cheap, modern structures could be built. All this because bribe money was going into corrupt pockets. “Anything to make another crooked dollar!”

As we continued to walk, Lee was plunged deep in memories. I again noted how he walked with his feet straight ahead at all times. Everything about Lee was straight, I mused — except for his ‘creative lies.’

“Oswald! Is that you?” someone suddenly shouted.

Lee looked up and noticed a thin young white man coming around the monument, carrying a Polaroid camera.]

“Thornley!” Lee answered.

“What are you doing here?” Thornley replied, breaking into a rambling lope. Reaching Lee, he grabbed his shoulders in a warm masculine greeting.

Kerry Thornley was a fellow Marine with whom Lee had served at El Toro Marine Base in California. Both wanted to become writers and see the world. Thornley said he lived nearby and invited Lee to play some pool with him, but Lee declined, saying he was going to take me out to eat. Thornley suddenly took our picture with his Polaroid, as Lee protested. When the picture scrolled out of the camera, Lee took it, watched it develop, and then tore it to pieces.

“Hey, what did you do that for?” Thornley asked. “I just wanted to give you and your wife a picture.”

“This isn’t my wife,” Lee said.

“You’re not? “ Thornley asked. I shook my head.

“We just found out we’ve been hired by the same company,” Lee said, “So we’re going out to celebrate. My wife won’t be here for a few days — and the same for her husband.”

“Are you sure that’s all there is to it?” Thornley asked, grinning.

“Tell you what,” Lee said. “Go ahead, take another picture.”

“I can’t.” Thornley said in a disgruntled voice. “That was the last one in the camera.”

Lee drew out a tiny camera from his shirt pocket. “Well, I have a miniature camera with me. I’ll show you how to work it, and then you can take another picture of us with that. Okay?”

It was silver, in a dark leather case with a chain hanging from it.

Very cool,” Thornley said, taking it from Lee and inspecting it. “You kept it!” It was a Minox—a tiny spy camera.

“You know I like photography,” Lee responded. “With this little baby, I can take pictures anywhere, and carry it in my pocket, unlike your Polaroid.”

Lee quickly showed Thornley how to use the camera, and Thornley snapped our picture (If I only had that photo!). Then Lee took one of Thornley.

Harry Lee as Sheriff of Jefferson Parish, Louisiana for 27 years, from 1979 until his death in 2007. Born in the back room of his family.’s Chinese laundry in New Orleans in 1932, he grew up working with his family. ’s Chinese restaurants. Lee attended LSU and joined the Air Force in the 1950s. In 1959 he returned to Louisiana and worked in his father’s restaurants, the most famous of which was the House of Lee, which opened in 1961. Soon Lee met Congressman Hale Boggs, who became his political mentor and for the next six years Lee moonlighted as Boggs’ driver whenever the Congressman was in Louisiana. In 1964 Lee was elected president of the New Orleans Chapter of the Louisiana Restaurant Association and presided over the peaceful racial integration of New Orleans restaurants in compliance with the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

After graduating from Loyola Law School in 1967, Lee practiced law until Congressman Boggs helped him get appointed first magistrate for the U.S. District Court in New Orleans in 1971.

“I develop ‘em myself,” Lee said. “I’ll bring you a print. Just tell me where you live.” The two talked awhile longer, then Lee and I continued to Reverend Jim’s, where we worked another two hours. With what we’d made the day before, we had enough money to pay for a good meal at the House of Lee, a Chinese restaurant owned by Harry Lee’s family. Lee knew Harry because he worked part-time with Lee’s friend David Lewis at the bus station to help support his big family. Harry Lee was there that night, and greeted us warmly. He insisted that we eat for free and saw to it that we were treated like celebrities.4

In 1972 Boggs invited him to travel to the People’s Republic of China with the Congressional Delegation led by Boggs and Representative Gerald Ford. (Both Boggs and Ford served on LBJ’s Warren Commission, and Boggs was killed in a plane crash after they returned from China). Publicly known as a zealous crime fighter, Lee was a political insider and had close contacts with Louisiana Governor Edwin Edwards. He also maintained close contact with Congressman Boggs’ family after his death.

In 1975 he became chief attorney for Jefferson Parish, Louisiana, and in 1979 was elected Sheriff. He immediately gave deputies raises and computerized the Sheriff’s Office. His popularity was confirmed by six re-elections despite many turbulent conflicts with the local media. Lee developed prostate cancer in 2007 and died of leukemia later that same year.

When Lee finally took me home, it was long past dark. We had once again been through a day filled with unexpected stress. Yet, in the end, we emerged relaxed and content with each other. We lingered on the front porch saying our long goodnight, as Collie came out from under the house and rested against our legs. Lee reminded me to meet him at 1:00 P.M. at Walgreen’s prior to our Reily interviews, so he could tell me how to mask the fact that we were pre-hired. I leaned against him, thinking of all we had been through.

“I just want to hug you, Lee,” I finally said. “Nothing personal.”

He laughed, and said okay. I then kissed his cheek. That made me very happy, so I kissed him on the mouth.

“Now I’ll be suffering all night because of you!” Lee said. “Heartless wench!”

“I can’t help it,” I replied. “You said it was OK to hug you.”

“Hug, not kiss! Bad Juduffki! How will I sleep? How will I rest? Now it’s my turn,” he said. “You have it coming to you.”

Lee reached for me and kissed me. The song, “Then He Kissed Me” came out later in 1963, and thereafter, whenever I thought of that kiss the song would roar through my head: He kissed me in a way I’d never been kissed before... in a way I wanted to be kissed forever more!

We broke away, our hearts pounding. “How are we going to handle this?” I asked.

“Slap me,” he suggested.

“I could never slap you,” I said. “I love you. Besides, then I’d never find out how the Adam and Eve story ended.”

“To make you happy is all I want anymore,” he said, his eyes cast down.

“Oh, Lee,” I answered, “... that’s all I want; to make you happy, too!”

He bent down and whispered, “But do you really love me, Juduffki?”

I was silent a moment, then whispered, “Yes.”

“Then I’m content,” he said. “I have to go now.”

He stroked my hair gently. Then he turned and walked away without looking back. I continued to pet Collie, wondering what in the world would happen next?

____________________________

1. Lee’s Aunt Lillian Murret told the WC she did not know that Lee had visited his father’s grave on Sunday. As I reported, Lee talked to his uncle about that. Soon after that statement, Lillian also mentions Lee trying to get a job “lettering”at “Rampart Street.”

Of course, Lee didn’t give away our work periods there, but may have had to explain his first contact with Rev. James:

From WC. Vol. VIII, pg. 46:

“Now what he didn’t tell me was that on Sunday he must have gone to the cemetery where his father was buried... anyway, Lee looked in the paper and finally he found this job - I don’t know where it was, but it was up on Rampart Street, and they wanted someone to letter.

Mr. Jenner: To letter?

Mrs. Murret: To do lettering work, yes, and so he called this man and the man said to come on out, so he went on out there to see about this job. First, while he was waiting for the appointment time, he sat down and tried to letter, and well, it was a little sad, because he couldn’t letter as well as my next door neighbor’s 6-year-old child, but I didn’t say anything, so when he got back he said, “Well, I didn’t get the job.” He said, “They want someone who can letter, and I don’t know how to do that.”

In fact, Lee didn’t want anyone to know that we went to Rev. Jim’s to make pin money (and would do so late in the summer, as well). Later, he would say he had worked at an address on Rampart at one time.

2. One researcher said a person had reported that Lee had been born into a Hungarian family and thereby knew both Hungarian and Russian fluently from childhood. Anyone who had spent time with Lee knew how hard he practiced his Russian. His ability to pick up language orally was rapid and excellent—probably a compensation for his dyslexia, which made him an excellent listener, but he did not know Hungarian. I have lost most of my knowledge of Hungarian over the years, but fifty years earlier, I knew some spoken Hungarian. Lee knew none.

3. At the library, Lee and I found the address of Evangeline Seismic, and I called them on Susie’s phone to locate Robert. They passed on my new address to Robert.

4. Harry Lee was interviewed before his death concerning whether he knew Lee Oswald. He claimed it was his brother, not he, who had known Oswald. Nevertheless, it was Harry, not his brother, who was so gracious to us that night.