— CHAPTER 15 —

DR. MARY

Saturday, May 11, 1963

Today was the day I would finally get to talk to the famous Dr. Mary Sherman. Using Lee as the messenger, she had invited me to have lunch in her apartment at noon. Dr. Sherman lived in the Patio Apartments on St. Charles Avenue near the corner of Louisiana Ave. It was so close that I could have walked there from my place on Marengo Street, but I preferred the refreshing streetcar ride. I entered her complex exactly at noon, and located her apartment at the far end of the elegant courtyard up one flight of stairs. At the end of the courtyard was a small patio, lush with plants and flowers in bloom, I stopped by the stairs and looked up. I saw the “J” on the door of her apartment and knew at once I wouldn’t have any problem remembering which was hers.

As I approached the door it opened, and Dr. Sherman stepped out to greet me with a gracious smile. “Judy, we’ve been expecting you!” she said in a warm, friendly voice. Dr. Sherman was dressed attractively in a peach-colored suit with her hair up in a French twist. She took me by the hand and guided me into her spotless home.

In the front room, lunch was already set out on a table decorated with fancy glasses and fresh flowers. Much to my surprise, there was a man sitting at the table smoking a cigarette. It was David Ferrie.

Dr. Mary Sherman

Dr. Mary Sherman was one of the most respected women in American Medicine. Born in Illinois in 1913, she studied in Europe and spoke several languages. In 1934, she then entered the University of Chicago Medical School and became friends with classmate Sarah Stewart, who later discovered the first cancer-causing virus.

Mary married Thomas Sherman, who paid for her medical education. But Thomas was an alcoholic, and their marriage was a disaster. Whether Thomas committed suicide or abandoned Mary is unclear, but she claimed to be a widow.

Dr. Sherman offered me a seat and presented me with a plate of finger sandwiches. Her soothing manner was entirely different from the stern woman who had cut me off so abruptly at Dave’s party. Today she was so hospitable that I soon let go of the humiliation of that earlier experience. When I addressed her as Dr. Sherman, she invited me to call her Dr. Mary instead. We had fruit compote, pastries, salad, and a conversation like none I had ever heard before.

Throughout the 1940’s, Mary continued at the University of Chicago, where she was trained as an Orthopedic Surgeon, and eventually became the Chairman of the Pathology Committee of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. Her main interest was cancer, and she published many medical articles in the field. While in Chicago, she was close to the legendary physicist Enrico Fermi, famous for the first sustained nuclear reaction, which paved the way for both nuclear power and the atomic bomb. Mary became an expert in the medical uses of radiation and wrote numerous articles on that subject. In 1953 Mary moved to New Orleans, where she became an Associate Professor at Tulane Medical School and a partner in the Ochsner Clinic. There she set up a laboratory, now named in her honor.

Dave and Dr. Mary had been chatting about the conquest of Mount Everest, but the conversation quickly shifted to medicine. Both Dave and Dr. Mary began describing chilling experiments on human brains being conducted at Tulane by Dr. Robert Heath. Heath’s most recent exploits were described in the newspaper on Friday. I had not seen the article they were referring to.

On July 21, 1964, hours before the Warren Commission began their investigation into Lee Oswald’s activities in New Orleans, Dr. Sherman was murdered. Her body was found naked in her apartment, her right arm and thorax had been burned completely off, but the rest of her body was not burned in the same manner. There were seven stab wounds to her body, one of which penetrated her heart and caused her death. In October 1967 Jim Garrison revealed that his investigation into the JFK Assassination had connected Mary Sherman to David Ferrie and hi-lighted their private cancer experiments with mice. She is the subject of the book Dr. Mary’s Monkey, by Edward T. Haslam.

Dave said, “Listen to this, J. ‘Dr. Heath Tells New Technique. Electrical Impulses Sent Deep Into Brain... [a patient]... had tiny wires implanted into precise spots in his brain. The wires were attached to a self-stimulator box, which was equipped at a push of a button to deliver a tiny, electrical impulse to the brain...’” Dave paused to let what he was reading sink in. “I wonder how many brains Heath went through before he had success with these two? How long did it take to find those ‘precise spots’ in their brains with his hot little wires?”

“Dr. Ochsner would never do such a thing,” Dr. Mary said, pouring me some tea.

“It sounds like science fiction,” Dave said. “Who knows what kind of mind control could be exerted over a brain, twenty or thirty years from now?”

“I doubt John Q. Public will ever have a clue,” Dr. Mary replied. “They certainly have no idea they were getting cancer-causing monkey viruses in their polio vaccines,” she added bitterly. Seeing my expression of shock, Dr. Mary went on to explain that she and a few others had privately protested the marketing of the SV40-contaminated polio vaccine, but to no avail. The government continued to allow the distribution of millions of doses of the contaminated vaccine in America and abroad.

Cancer-causing Monkey Virus

In 1957 Sarah Stewart, MD, PhD of the National Cancer Institute and Bernice Eddy, MD, PhD of the National Institute of Health discovered SE Polyoma, a cancer-causing virus present in their laboratory animals. It was soon cataloged as Simian Virus 40 (SV40), and it’s origin traced to monkeys. Studies around the world soon confirmed SV40 as a cancer-causing agent.

She said she was told that the new batches of the vaccine would be free of the cancerous virus, but privately she doubted it, noting that the huge stockpile of vaccines she knew were contaminated had not been recalled. To recall them would damage the public’s confidence, she explained.

Upon the discovery that SV40 was present in both of the polio vaccines produced from Rhesus monkey kidney cells, a new federal law passed in 1961 mandated future vaccines should not contain this virus. However, this law did not require that SV40 contaminated vaccine stocks already produced be destroyed, so distribution of the tainted vaccine continued until 1963. Bottom line: the Boston Globe estimated that 198 million Americans were inoculated with SV40-contaminated vaccines between 1955 and 1963. Some critics have alleged that SV40 remained in the polio vaccines until the 1990s. Recent biopsies of tumors found SV40 in a variety of soft-tissue cancers, although the American government continued to dispute its causal role.

I was speechless. Were they telling me that a new wave of cancer was about to wash over the world?

“The government is hiding these facts from the people,” Dave said, “so they won’t panic and refuse to take vaccines. But is it right? Don’t people have the right to be told the contaminant causes cancer in a variety of animals? Instead, they show you pictures in the newspaper of fashion models sipping the stuff, to make people feel it’s safe.”

My mind raced. It was 1963. They had been distributing contaminated polio vaccines since 1955. For eight years! Over a hundred million doses! Even I had received it! A blood-curdling chill came over me. Their words seared into my soul.1 The scale of the accusation confounded me. The thought of a cynical bureaucracy that put its own reputation over the fate of millions of innocent people settled into me like a poison.

Dr. Mary said she’d received threatening phone calls, so she gave up protesting publicly. Instead, she and Dr. Ochsner started working privately on ways to fix the problem. Together, they tackled the world of cancer-causing monkey viruses to see if they could figure out how to defuse them. For the past two years, they had been subjecting these monkey viruses to radiation in order to alter them into a benign form.

“We’re not quite sure what we have on our hands, now,” Dr. Mary said. “Our work altering the simian viruses led to the development of some rare and potent cancer strains that seem facilitated by their presence.”

I had brought along the research papers Dr. Ochsner had given me, having spent the last several hours frantically reading as many as I could to prepare for this lunchtime meeting. I had read enough to participate in the discussion, and to comprehend these revelations, but nothing could prepare me for what I was about to hear.

“As you know,” Dr. Mary said, “we’ve been working for some time on a project.”

“I heard you hit a stone wall,” I commented. “Dr. Ochsner told me,” I said, thinking I knew where she was going with her comments.

“But we may have hit upon a viable means to eliminate Fidel Castro, by what will appear to be wholly natural causes,” she said.

“No more poison pills, bazookas, or exploding cigars,” Dave said. “The Beard is on to all that. Everything’s been tried.” Dave lit a new cigarette before his other cigarette was finished. “We worked together,” he went on. “All of us. The anti-Castro people. The CIA. Cosa Nostra. The best mercenaries in the world, but he’s defied the odds. Do you understand?” I nodded cautiously.

“We became a machine ready to kill troublemakers who threatened American interests anywhere in the world. It was supposed to be able to wipe out Fidel,” Dave said as he studied his cigarette, then took another deep drag. “The problem is that a certain man says he will dismantle our machine if it doesn’t obey him. This man is the most dangerous threat to America of all. He is soft on Communism. He refuses to go to war. He lets his baby brother go after the Mob, and errant generals. He plans to retire Hoover and wants to tax “Big Oil.” He thinks he can get away with it, because he’s the Commander-in-Chief.”

I caught my breath, and glanced at Dr. Sherman as she began taking dishes from the table. The frown on her face told me they were deadly serious. Dave cleared his throat and coughed. “They’ll execute him,” Dave said, “reminding future Presidents who really controls this country ... those who rise to the top will gain everything they ever hoped for, and look the other way.”

Dave’s hands trembled as he spoke. His nerves were as raw as his voice.

“If Castro dies first, we think the man’s life might be spared.”

“How?” I asked, as the weight of his comments began to sink in.

“If Castro dies, they’ll start jockeying for power over Cuba,” Dave said. “It will divide the coalition that is forming. It may save the man’s life.”

“Where ... how did you get this information?” I pursued

“You’re very young,” Dr. Sherman said. “But you have to trust us, just as we have to trust you. If we were really with them, you wouldn’t be privy to this information. These people have the motive, the means, and the opportunity. They will seem innocent as doves. But they’re deadly as vipers.”

“What about Dr. Ochsner?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” Dr. Sherman said. “I can’t tell. Perhaps...”

“He’s an unknown element,” Dave broke in. “But we know he’s friends with the moneybags. He thinks Mary and I hate ‘the man,’ just as he does.”

“Would he go so far as to— “ I started to ask.

“I think he might aid others,” Dr. Sherman said. “Perhaps without even knowing it. He functions as a go-between. His interest was originally to bring down Castro, because he’s anti-Communist to the core. But he’s remarkably naïve.”

Dr. Sherman explained that in the past, Cuban medical students came to the Ochsner Clinic to train. Now Castro was sending Cuba’s medical students to Russia. Ochsner resented this rejection. Some of those medical students realized that studying with Ochsner could have made them rich and famous, so they were bitter about Castro’s denying them that right. Some of them were bitter enough to help kill Castro. Dr. Sherman’s comments called to mind Tony’s similar degree of hatred.

“The clock is ticking,” Dave said. “It’s going to require a lot of hard work if we’re going to succeed where all the others have failed.”

“We believe we have something,” Dr. Sherman said. “But we want to see what you make of it,” soliciting my opinion and gently stroking my ego with her words. “Dr. Ochsner says you have serendipity.”

“Yes,” I replied. “He told me that.”

“It’s a rare compliment,” Dr. Sherman went on. “You induced lung cancer in mice faster than had ever been done before, under miserable lab conditions.” Dr. Sherman reached over and took my hand, squeezing it warmly. “That’s what Ochsner likes about you. Your serendipity. And we know you’re a patriot. That’s why you’re here.”

“This is lung cancer we’re talking about,” Dave said as he began smoking his third cigarette in five minutes. “Your specialty.”

“That’s what they wanted me to work with, ever since Roswell Park,” I admitted.

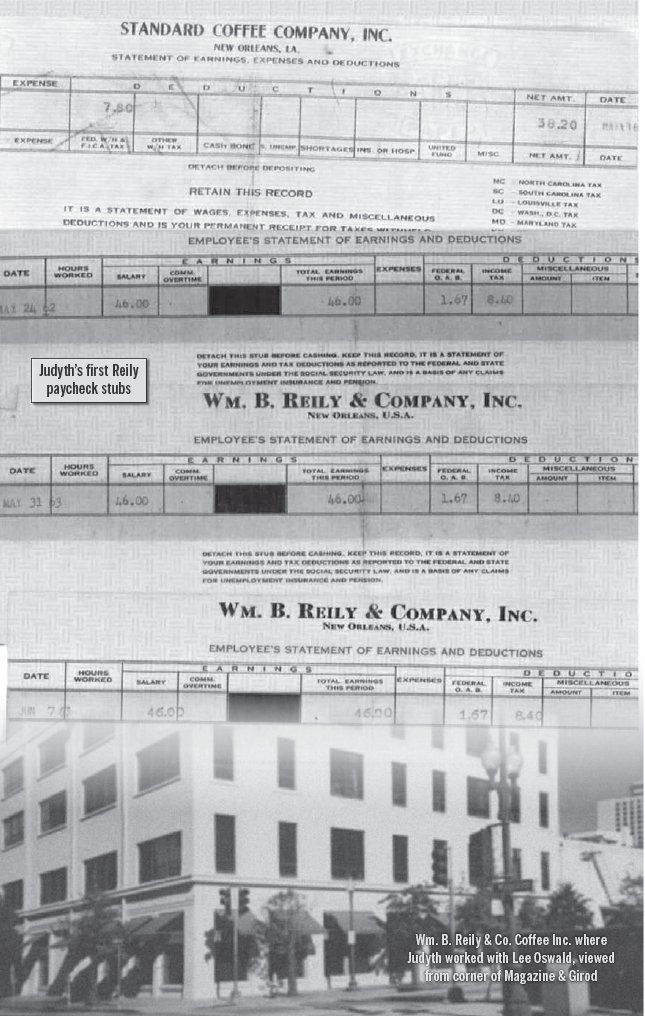

“You’re untraceable,” Dave continued. “With no degree, nobody will suspect you, because you’re working at Reily’s, and you’re practically a kid.”

“We have only until October,” Dr. Sherman said.

“Maybe until the end of October,” Dave amended, as he snubbed out his half-smoked cigarette.

“You can still choose not to participate,” Dr. Sherman told me.

“Yeah, we’ll just send you over to Tulane to see Dr. Heath. A few days in his tender care, and you’ll never even remember this conversation took place,” Dave said.

“You’re not funny!” Sherman snapped at Dave, seeing my face. “Of course, nothing will happen to you, Judy. Dr. Ferrie and I are the visible ones, not you.”

“Hell, I was joking,” Dave said.

“She is so young,” Dr. Sherman said reproachfully. “You frightened her.”

“I’m sorry, J.” he said. “What are you, nineteen?”

“I will be twenty, on the 15th,” I said softly.

Dr. Mary saw that I was trembling. She poured me a little glass of cordial and offered it to me, saying that it would relax me, but I declined to drink it.

“All I came here for was to have an internship with you, Dr. Sherman,” I said, adding that I still wanted to go to Tulane Medical School in the fall.

“Don’t worry, you’ll be there,” Dr. Sherman said. “Dr. Ochsner said he’ll sponsor you. That’s set in stone.” She paused. “We will not mention this again, at any time .... Take all the time you want to decide,” she added as she gently grasped one of my hands. “If you say no, I’ll just have you work in my lab at the clinic three afternoons a week. That way, you can fulfill the terms of your internship, while still working at Reily’s.”

Dave got up and started pacing the floor. “You got onto the wrong side of this project by accident,” he said. “It was a matter of bad communication and timing. Ochsner always intended to have you involved, but it was supposed to be unwitting.”

“I wish it was unwitting,” I said.

“You can always let me hypnotize you,” Dave offered, trying to find some humor in the situation.

“No, thanks,” I said.

Gloom settled into the room. I noticed a large pastel painting hanging over Dr. Sherman’s mantel depicting a series of dramatic scenes, such as a bull being killed with a sword, and a woman being stabbed by a Roman soldier. The whole painting was about brutality and death. “What have I gotten myself into?” I thought to myself.

“I want to think about this for awhile,” I said.

“Take your time, Judy,” Dr. Sherman replied. She got up and went over to the kitchen counter where two microscopes sat next to a rack holding probably sixty test tubes, turning slowly under a light. I recognized this round rack from my work in the lab. Each test tube held a clear pink liquid in which cancer cells were growing. A motor rotated the rack, shaking the tubes slightly as they turned. Every three days or so, the fluid had to be replaced. About once a week, the cells were loosened from the glass and transferred to new test tubes, so they wouldn’t choke each other to death.

“I have something to show you. Before you say ‘Yes’ or ‘No,’ I want you to inspect these first,” Dr. Sherman said, as she motioned for me to sit down on a stool at the counter. Then she handed me a stack of glass slides to view under the microscope. Each slide was carefully labeled, and they were in sequential order. The age of the cells was indicated by hours and minutes, and clearly displayed so one could see how fast they were growing. I looked at several slides. What I saw was familiar. These were normal cancer cells.

Then Dr. Mary gave me a second set of slides to inspect. I looked carefully, first at one slide, then another ... and another ... I couldn’t believe what I was seeing

“I’ve never seen anything like this,” I finally said aloud, as I continued to recheck the ages of the cells at various stages, and saw how rapidly they were dividing. “These are monsters!”

“They are, aren’t they?” Dr. Mary said.

It wasn’t their size that got my attention. It was their aggressive growth rate. These lung cancer cells were phenomenal. I had never seen such a fast and furious rate of division. The scientist inside me suddenly woke up. I began to get excited.

“I need to see all the log books and reports. Whatever statistics you have.”

“I’ll get them,” Dr. Sherman answered, knowing that the hook was in.

“Somebody bring me a note pad,” I said, not looking up from the microscope. “I assume you have electron microscope studies on these things, right? Do you have photos?”

“We have them,” Dr. Sherman confirmed.

Dear God! I thought to myself, I am looking at the most deadly lung cancer cells in history. Here, on somebody’s kitchen counter. Who would ever believe me?

“Well, J,” Dave said, “now what?”

Just then the phone rang. Dr. Sherman answered it and handed me the phone. It was Lee. He said he was at a grocery store and was in a hurry.

“They’ve arrived safely,” he said, referring to his family. “All is well. I’m picking up groceries now. They’re waiting for me in the car.”

“You sound happy,” I said. “I’m glad.”

“Well, I am happy to see her, I can’t deny it,” Lee said. “So far, she’s been nice to me, and my aunt and uncle already like her.”

I was not prepared for his next statement.

“But I feel like I’ll be cheating on you, if I sleep with her,” he said. “I’m calling to tell you that.”

“I’ll have the same problem when Robert comes back in town,” I said, turning my back to Dave and Dr. Mary, hoping they couldn’t hear me. “How will I be able to say no to him? He’s my husband. Besides, I still love him. It’s just not the kind of love I have for you.”

“I feel the same,” Lee said.

“Just don’t hit her anymore!” I reminded him. “You said it would prove you loved me.”

“OK, just let me come over sometimes, if she riles me too much,” he said. “I have to go now.” With that, he hung up.

“Was that Lee?” Dave asked.

I nodded, then blurted out, “We’re falling in love, and we’re both married.”

Dr. Sherman turned suddenly, her eyes laced with some inner pain. “Who do you love more, your husband, or Lee?” she asked.

“I think I’ve already said too much,” I answered.

“Whatever you do,” Dr. Sherman advised, “Don’t stay with a man simply because you feel obliged to do so. He might turn out to be an albatross around your neck.”

“She speaks from experience, J,” Dave said.

“Getting married was the worst mistake I ever made in my life,” Dr. Sherman said. “It ruined my life. I hope it doesn’t ruin yours.”

“Probably the stupidest thing you ever did was marry Robert Baker,” Dave said.

His criticism did not sit well with me, nor did Dr. Mary’s advice.

“I wish to remind you both that I came here two weeks early,” I said. “It’s easy for you to give me advice now, after the fact. But where were you when I had to pay my rent? He came and married me,” I said hotly. “And Dr. Sherman, you walked away from me when I tried to talk to you at the party. That hurt.”

Mary Sherman sat down on her couch, and motioned for me to sit with her.

“I’m sorry, Judy,” she said. “I meant to get in touch with you about that. I should have called you immediately. But I had to go out of town the next day. And then it slipped my mind.”

“Well, I have to divorce him,” I said.

Dave suddenly changed his position.“Don’t divorce Robert yet,” he advised. “There are advantages to having the name Baker.”

“The name ‘Vary’ is rare,” Dr. Sherman added. “People can look it up and discover your past, and your experience with cancer research. They might figure out who you are and why you are here. But nobody has heard of Judyth Baker. You’re protected by his name.”

“Hey!” Dave said, smiling, “Dr. Ferrie, Dr. Mary, and Dr. Vary! How about that? But seriously, J,” he went on, “keep your ‘Vary’ name as low profile as you can. Among us, you’re J. Vary, but in the big, bad world out there, you’re Mrs. Baker, just a secretary at Reily Coffee Company. It’s really a fortuitous thing. Stay married to the guy. At least until your work here is done.”

With that, Dr. Sherman handed me a key to her apartment and a note card with her maid’s schedule on it, saying that it would be best to avoid running into her. I went back home to see Susie and her dog Collie, hoping for some normalcy in my life, which was getting stranger by the day.

Sunday, May 12, 1963

On Sunday morning, I rested in bed, reviewing all the events and people in my life. Finally I got up, and stared at the stack of medical reports that I had to read. Just then Susie knocked on my door, saying she had made me breakfast. I told her to come in.

“I get worried about you,” Susie said, setting down the little tray. I thanked her and gratefully began to nibble on some toast. I told Susie that Lee had promised not to hit Marina again, but might need a place to calm down if they had a fight.

“I suppose it would be the Christian thing to do,” Susie said. “Why not make an extra key, and give it to him?”

I gave Susie a hug. “You’re too good to be true!” I told her.

“My Bill knew Lee’s uncle Dutz a long time,” Susie said. “They worked the docks together before he went to sea. Dutz was always good to Bill, and Lee’s his nephew. It pleases me to help him out, if I can.”

Susie then asked if I’d like to go to church with her, but I declined. I spent the day reading medical reports.

Monday, May 13, 1963

I got dressed and headed for the Magazine Street bus. When I got on, Lee was sitting in the back reading the newspaper. I sat in the seat directly ahead of him, but did not turn around to talk.

When we got off at Reily’s, Lee said, “I’ll be over to help you with the background report after lunch.” He gave me a look, and then we clocked in. Lee walked to the right, into the production side of the Reily building, and I went back outside, heading to the Standard Coffee office across the street, where I was soon joined by Mr. Monaghan.

“Time to go over to Congressman Willis’ office,” he said. “After that, we’ll visit the Retail Credit company and go over some of their files, so when you meet with Oswald, you’ll know what to do.”

Monaghan and I walked about a block and entered a stone building with thick columns and interesting statues at the roof’s pinnacles. Inside, building materials and boxes cluttered the marble halls.

“They’re renovating the building,” Monaghan said. “The attorneys and courts are all moving. Today you’ll meet Willis’ secretary. Then, whenever I send you over here, she’ll know who you are.”

Willis’ secretary had been with him for years. From her loyal perspective, there was no greater patriot than Congressman Willis. She proudly showed me a stack of letters from constituents and political friends, encouraging Willis to keep fighting Communism and to never give up the battle. I could not help noticing that some letters also condemned President Kennedy and his policies. Others attacked Kennedy for firing racist Army General Edwin Walker. Another favorite topic was a call-to-arms to ‘Impeach Earl Warren,’ the liberal Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Willis’ secretary was quite pleased that her boss was about to head the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

“He’s in Washington right now,” she said, “but he’ll fly in next week. He goes back and forth, you know.”

“Ask Mr. Willis to call me with respect to a young man we have recently hired,” Monaghan told the secretary. Apparently Monaghan wanted Willis to know who Lee really was.

Congressman Willis

Edwin E. Willis was born in 1904 in Louisiana and, after practicing law in New Orleans for several years, was elected to the Louisiana State Senate in 1948. Less than a year later Willis, a Democrat, was elected to the United States House of Representatives where he served until 1969. During his tenure, Congressman Willis served as Chairman of the House Un- American Activities Committee (HUAC) from 1963 until 1969. He died in 1972.

After leaving Willis’ office, Monaghan stopped in the hall to describe the task before us. We had to get some blank report forms from Retail Credit. These would be necessary to create Lee’s bogus background report. It wouldn’t be easy, because Retail Credit executed tight control over anything with their logo on it as a matter of professional integrity. We arrived at their office at about 9:30 A.M., and Monaghan introduced me to the supervisor, Mr. Henry Desmare, who gave me his card. Desmare was in charge of three or four men, who were frantically working the telephones. Desmare said his investigators spent considerable time on the phone, but sometimes they visited character references in person. While his underlings investigated unremarkable and conventional individuals, Desmare and another supervisor handled the background investigations of important people, such as executives. Those reports were more expensive, and thoroughly detailed.

Desmare treated Monaghan with great respect, mostly due to commercial interest. The Vice President of Wm. B. Reily & Co. Inc. represented an important account. Monaghan wasted no time requesting access to Desmare’s extensive files, and said he had the name of a candidate who could replace one who hadn’t passed muster, due to a drunken driving charge. The new applicant’s former boss had mentioned a favorable report from Retail Credit, and Monaghan wanted to save Standard Coffee an employment agency fee. This was classic Monaghan manipulation.

Mr. Desmare had no choice but to allow Monaghan access to his files, because he couldn’t risk irritating an important client over such a small request. Desmare knew that Reily was building a big new factory for producing instant coffee and roasting beans. They would be hiring many new employees by the end of the year, and that meant lots of background reports from Retail Credit. Monaghan eventually found a carbon copy of the report in question, and the three of us sat down at one of the empty desks to review it together. Monaghan and Desmare explained how I should interpret what I saw.

Once Monaghan had Desmare’s complete cooperation, he handed him my Reily job application, and basically told him to hire me. They asked me a few simple questions and typed up my “background report” right there, as I stood in Retail Credit’s office with Reily’s VP watching them.

“We’re going to be doing a lot of hiring soon, so I’d like Mrs. Baker to see some negative reports,” Monaghan said. “All we have in our files are reports for people we hired, which are, of course, not negative.”

Mr. Desmare had no problem with that, he said, as long as I pledged confidentiality. Once I did, he pulled out a stack of carbon copies of old reports prepared for Reily’s.

While Monaghan and Desmare intermittently discussed Reily’s new contract, I was asked to type examples of negative comments on a couple of blank report forms, which Monaghan insisted he needed for his secretarial training manual. Monaghan commented that Reily’s would probably continue its relationship with Retail Credit, as he was pleased with the quality of its reports to date. They talked for about an hour, until Mr. Desmare noticed how much trouble I had typing the sample reports.

“The carbon keeps getting wrinkled,” I said lamely. “How in the world do you line up this onion-skin paper, so it doesn’t slip?”

“You’ll have to retype that more neatly later,” Monaghan said, as he scooped up a few empty report forms.

“I’ll have her work on this at our office,” he said to Desmare as he prepared to leave.

“I would prefer you didn’t take any of those,” Mr. Desmare objected. “They’re company forms.”

“I know,” Monaghan said. “But I want her to type up some anonymous examples to put in our training manual. If the manual had some negative examples in it, I wouldn’t have had to waste my time bringing her over here.”

Monaghan had pinned Desmare. He really could not object further. Out we went with their precious forms in our grubby paws. We now had what we needed to create a report to turn “defector Lee” into a model citizen, so he could pass Mr. Reily’s muster.

“You got them! I am so impressed, sir,” I told Monaghan, as we headed back to Magazine Street.

“Of course I got them,” he replied. “I get everything I want.”

When we returned to Standard Coffee’s office, Monaghan searched for a typewriter with a typeface that matched Retail Credit’s typewriter. He found one in Reily’s main office, and had it brought over to ours. I started to realize how careful this “former” FBI agent could be.

Working with Monaghan was like working with a police sergeant. He would stand at his desk like a bird of prey, staring at the rows of women working on billing records, and watching to see if anyone shrank from their duties for the slightest moment.

Monaghan knew I would only be at Reily’s temporarily, so he didn’t bother to give me a real desk. He told me I could sit at his desk when he wasn’t there, but when he was, I had to move over to a little extension desk that adjoined his. I called this my “half-desk.” As a consolation prize, Monaghan gave me a nice nameplate to display on his fine, dark walnut desk when he wasn’t there.

As the summer progressed, Monaghan was gone more and more often. I was not privy to what he was doing during these absences, and sometimes the workload was very heavy. I came to realize that his employment at Reily’s was as much of an arrangement as were Lee’s and mine. Monaghan was the first non-family Vice President that Wm. B. Reily Coffee Company had ever had.

Lee walked in just as Monaghan was leaving, and in a few minutes we were out the door to have lunch together. I told Lee about my morning, and he told me about his.

“It sounds like you’re going to be busy,” I said.

“Today, yes,” Lee told me. “And tomorrow afternoon I have to go to Baton Rouge on business. You’ll have to clock me out at five o’clock.”

“But I get off work at 4:30,” I protested. “Do I have to wait until 5:00 to clock you out?”

“Most mornings I’m going to be coming in about 8:30,” Lee said, “because I usually have a meeting somewhere else first. I could even show up later than 8:30.”

I gloomily realized I would have to be at work from 8:00 A.M. until however long it took Lee to accrue his eight hours. If Lee was to be clocked out at five every day, I’d be putting in two-and-a-half extra hours a week. Lee explained there were advantages in this arrangement.

“You’ll be at Dave’s, and at Dr. Sherman’s apartment two or three afternoons a week,” he reminded me. “Sometimes I’ll help you there. You’ll be out of Reily’s at least ten hours a week.”

“You forget that the real rat race, or should I say ‘mouse race,’ will be going on at Dave’s,” I reminded him. “And then I’ll have a lot of work to do at night back at my place. Writing reports. Reading papers. Studying photos.”

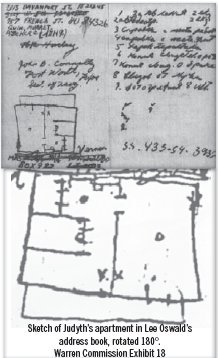

“That reminds me,” Lee said, taking out his address book. “I need to sketch a layout of your apartment.” He found a page with room for the sketch and turned his address book upside-down. “That makes it a bit harder for others to recognize,” he said, as he sketched. “I always assume this book might be read at any time by someone else.”

Finishing the sketch, he said, “All right, here’s your porch, the door, and the living room. There’s the window that’s not blocked by your bed. Here’s the big bathroom with no bathtub yet, and here’s where the hotplate and counter is, where you still don’t have a kitchen.” Lee had drawn an indentation there. He added lines showing the back entry and a step that led into Susie’s kitchen. “Now, where will you be hiding your lab papers and notes?” he asked.

I understood. If Robert ever saw those materials, he might wonder about them.

“Susie said I can give you a key,” I told him. We decided that it would be placed on a high ledge near the utility box, near the door to Susie’s kitchen. I could store the microscope box on a high shelf in the living room, and the papers on a book-case in the bedroom, under my folded clothes.2 “If anything happens to you, we will need to remove things right away,” Lee said. “We don’t want Robert seeing any of this.”

If anything happened to me?

Lee put an X on the proper places.3 “I remember some overhead lights,” he commented. As I pointed them out, he drew some little circles. I asked why he wanted to know. “It could save time at night,” Lee said. “Those lights have wall switches.”

I finally got the courage to ask how it went with Marina.

“She was nice to me,” Lee said simply. “We’re trying to get along. Ruth Paine is already being a pain, though.” (From then on, Lee always called her “The Pain.”)

Lee said he believed Ruth wanted Marina to divorce him. “She acts like a lesbian,” he said. “But maybe I’m reading too much into it.“

“How did she get involved with Marina?” I asked.

“She was selected to babysit Marina and Junie for me. But she’s not to be trusted, or her corrupt friends.”

“But Lee,” I protested, “You are living like a Spartan, posing as a person unable to thrive in this country, and later, you’re planning to pose as a friend to Castro, in an anti-Castro town. Did Marina agree to that life?”

“She was happy enough in Russia with an apartment to ourselves. She was content with just a few things.” Lee said. “But now it’s different. Now she wants everything. A car, a house, new furniture. She will have it, or else,” he said. “I can’t provide her those things and still look like a financial failure. I never cared about any of that in the first place. We are completely incompatible.”

“I know,” I answered. “But what are you going to do?”

“The Pain is going to stay in town until Tuesday,” Lee said. “After she leaves, I’ll try to reason with Marina. I’ll give her little things she wants, within my means, to make her comfortable. If only she’ll be patient. Otherwise,” he said, with sudden heat, “back to Russia with her. Let her see if anybody there will give her a better life than I did!”

Seeing it was time to change the subject, I told Lee I still had no letter from Robert. “My birthday is Wednesday,” I added. “I’ll no longer be a teenager! But I think he’s forgotten.”

“Well, I’ll make sure you won’t be forgotten, but I can’t help you celebrate on Wednesday,” Lee said. “I’ll have to be with my wife. It will be only the second night without Ruth. I need to spend time with Marina, because she thought I forgot our wedding anniversary. It couldn’t be helped,” he added, apologetically.

Lee leaned over and gave me a tender kiss. “No sadness about your birthday, now, Juduffki,” he said. “You’ll soon see what I’m arranging for us. We’re going to have our own chance for happiness. You don’t care if it’s Spartan, do you?”

“My dear Scarlet Pimpernel,” I said, “ If we can be together, let it be in Antarctica, for all I care.”

We finished our lunch and returned to the Standard offices, where we sat down to look over what I’d typed on Lee’s fake background report.

“I used 757 French Street, your aunt and uncle’s address, as your residence.”

“That’s just fine,” Lee said. “Nobody will care.” He looked over the form, and began to smile. “Hmmmm! We can have some fun with this,” he said. “Let’s make Lee H. Oswald a successful capitalist pig. Happy. Content. Perfect and prospering, with a loving wife and child.”

“OK,” I said. “Here goes!” (See the credit report form on page 294.)

Wednesday, May 15, 1963

It was my 20th birthday. I was no longer a teenager! Would my husband Robert even remember?4 On the bus, Lee was in a glum mood. He confided that he’d “done everything this morning.”

“I changed the baby, made coffee, fed the baby. I fixed my own lunch, washed out a diaper and, as usual, Marina wouldn’t get out of bed.”

“She’s pregnant. Maybe she didn’t feel well.”

“She was okay,” Lee asserted. “But Junie was crying, because I had to leave. Marina just stayed in bed, and let her cry!”

He said he placed Junie next to Marina, but she kept begging for him to stay.

“Make sure Marina goes to bed really early,” I suggested. “Then she’ll wake up earlier.”

“Fat chance of that,” he answered. Then I shoved a letter into Lee’s hands.

“Look at my birthday present from A-l,” I whispered, so bus riders couldn’t hear.

Inside was a demand for my first paycheck.

“It isn’t fair!” I said. “Susie needs her rent money on time next month, but now, I won’t have enough. We’ve been eating breakfast there every day, too. And her electric bill is due.”

“Well,” Lee said, taking the letter, “I can handle this. Since I can’t be with you tonight to help you celebrate, at least I can go to A-l, and talk to them.”

“Oh, thank you!” I put my hand on Lee’s, and he slid a little closer to me. Our eyes met, then we looked away.

I finished the phony background report on Lee, dated it May 16, and placed the original in the manila folder, for Lee’s transfer from Standard Coffee to Reily’s on Thursday.5 I worked on improving my typing speed, and learning protocol and procedures from the vice president’s secretary’s manual. It was tedious, and lunchtime couldn’t come soon enough. Lee made life more interesting with some good news.

“I found out that Banister’s secretaries never doubted you were Marina. Especially after you mumbled some Russian. So let’s practice it some more. Even though Marina’s in town now, we can find ways to be together and do things, because you can still pose as her. She’s not really showing yet.”

Turning the subject away from Marina, I asked if he’d found a chance to deal with A-l.

“First I went to the state employment agency,” Lee said. “I pretended I still didn’t have a job, so they gave me an appointment card. Then I went over to A-l and showed them the card. That made them think I was still job hunting. Our friend, ’Miss-Ogynist,’ found a photo job for me to check out. I almost thought about responding,” Lee said, smiling. “I have to clean out the roasters Friday, and I hear it’s not as much fun as photography.”

“Not nearly so much,” I agreed.

“After she gave me the referral,” he said, “I snowed her your letter, and told her I was upset. How dare she agree that I could make a call to you, then charge you a week’s wages?”

“Did she get mad?”

“Yes, but I told her this would be the last time me or my friends would ever darken A-l’s door, if she didn’t at least cut your fee in half.”

Lee handed me an envelope. “Look at this.”

I opened it, and saw a bill for 35% of the original amount.

“You did it, my darlink!” I said, with a fake Russian accent.

“She wrote out new terms,” Lee said. “Just one payment, then it’s over. And it won’t be due until after you’re paid, on the 24th.”

That evening, Lee and I rode the Magazine Bus all the way to Audubon Park, where Lee let off steam about his marital problems. He told me Ruth Paine hadn’t been gone an hour before he and Marina had an argument over how to discipline Junie. Their toddler was getting into everything. Lee and I both believed that children could be disciplined without violence, while Marina slapped Junie to correct her. “The first thing I said when she slapped Junie was, ‘I hope you go back to Russia!’” Lee admitted.

“Change your pattern,” I said. “It’s pure habit. Instead of yelling at her, do something else. Walk out, if you have to. You can choose to change.”

As we rambled through the park together enjoying the spring flowers, Lee felt his spirits rising. By the time we got on the bus and rode back, he was planning to take his wife to the zoo. “I’ll take her crabbing too,” he said. “I’ll get her away from the baby for a day. Maybe she’ll have fun, if we go by ourselves.”

It sounded good to me. We kissed quickly just before Lee got off the bus, and the driver gave us a wink.6 I got off at Marengo, and walked slowly toward my apartment. I entered through the kitchen to say hello to Susie and Collie. Had Robert remembered my birthday? After having some dumplings and milk, I finally checked the mailbox. Yes! There was a letter. It read:

“My Darling Judy,

This is the back of a seismic record & the pen I’m writing with is the one I use to number seismic bumps with... Breakfast is 5-5:30 and supper is 4-4:30 P.M., or maybe an hour or 2 hours later. After that, there’s just time to shower & relax enough to sleep. I haven’t figured out how the workday can be so long & so short at the same time. Today the boss has gone ashore, so I get a chance to write. The French they speak around here is terrible.... “

I found Susie and proudly read my love letter to her. But Susie again observed that Robert didn’t ask how I was, or why I had moved to a new place. Nor did he tell me when he was coming back.

“The work is really rough. It amounts to 6 hrs/day if I go out on the boat and 4 hrs/day if I stay here. The rest of it is eat, sleep & read. (There’s an extra 3 hrs on the boat because it takes that long to get out & back). Then again, the first day I started work, the boat to take us to the quarter boat (here) broke down, and the work day was noon ‘til 8:00.

He wasn’t being overworked, that’s for sure! Well, at least he had written. That was worth something, I told myself, though he’d obviously forgotten my birthday. I had research papers to read, so there wasn’t time to mope.

There was absolutely nothing romantic about the letter. In fact, it could have been written to a man, except it ended with my favorite words, “Love, Bob.” In my emotionally tangled mind, I weighed the factors. Robert’s influence in my life was shrinking, but coveting Lee’s attention wasn’t fair to Marina. She, too, was a stranger in a strange land. She, too, needed Lee’s love and care. And many men who have an affair return to their wives after their fling. There was no safe haven.

Since Robert didn’t mention receiving the letter I’d sent, I was afraid to direct another one to the beer and bait store. I’d have to wait for his return. Susie went to the deli and brought back a slice of carrot cake with a little candle on top. I wondered, as I blew out the candle, how my family in Florida was doing. They would have given me a birthday party. Homesick and sad, I felt guilty, but I sure didn’t want my parents to know I had ignored their advice and eloped, only to find myself left alone.

Thursday, May 16, 1963

Back at work, one day before our transfer from Standard Coffee to Reily Coffee, I handed the finished background report on Lee to Monaghan, who then took me to Reily’s. I learned who the salesmen were, saw their client lists, and accessed maps to trace their sales routes across the various states. After that, Monaghan escorted me into the attached five-story building where Lee and many others labored.

It was a factory workplace filled with machinery. Here were the hard-working employees, some of them Cuban girls with kerchiefs tied over their hair so it wouldn’t get caught in the machinery. Supervisors hovered around them, working as hard as their underlings. The thumping of rollers and motors filled my ears as the packing lines and conveyor belts moved rows of coffee cans and boxes of tea along. There was no air conditioning, and though it was only May, it was uncomfortably warm. Each floor was full of machinery, sacks of products and stacks of supplies. Coffee dust floated everywhere. I saw Lee moving through this haze, adjusting a belt here, squirting some oil there. He spotted me looking at him.

“Mr. Oswald!” Monaghan called out, raising his voice over the noise of the machines. “Please come over here!” Lee went over and stood before Monaghan as if he were a soldier. His hands were dirty, and there was grease on his shirt.

“Yes, sir?” he said.

“I’ve been advised that you have satisfactorily passed your training sessions,” Monaghan told Lee, making sure his main supervisor, Emmet Barbe, heard everything.

“Tomorrow morning, you’ll clock in and go to the Standard offices, prior to your permanent transfer to Reily’s. Mrs. Baker will meet you at that time. She will personally carry your Standard files over to Reily’s, and will adjust your time card and records to reflect that transfer, so your paycheck can be issued tomorrow without any delays.”

“Thank you, Mr. Monaghan,” Lee said.

“Congratulations!” Mr. Barbe chimed in.

Lee then excused himself, and left the area to go to another floor, while I was introduced to the supervisors in charge of the packing and shipping areas. They needed to know who I was because it would occasionally be necessary for me to stop a shipment, change an order at the last minute, or add a special order to help fill a truck.

After more training at Monaghan’s desk, including how to use a dictaphone, he asked me to reproduce a business letter. I created two decent samples before lunch. Monaghan reviewed the letters and was pleased, despite the fact that it had taken me almost an hour to type them.

“God help us if you had a dozen letters to type. You’d be here until midnight. I hope the doctor’s project will be finished before I lose patience with you,” he finished.

Miffed, I stood up for myself, telling Monaghan that “losing patience” with me was disrespectful. No secretary could handle the research and lab work I had agreed to conduct. From that moment, Monaghan treated me more thoughtfully.

From his remark about “the doctor’s project,” I was certain Monaghan knew about its existence, but I don’t think he knew any significant details.

Just before lunch, Dave Ferrie called and told me it was time to make a dry run to his apartment, to calculate the time it took to get there and back. I would have to return by 4:30 to clock myself out and stay on Reily’s premises until Lee’s time card hit eight hours, rounded to the nearest half hour.

Since Lee hadn’t been on the bus this morning, I was worried I’d have to wait longer than usual, but in fact Lee had barely missed the bus and Mr. Garner drove him to town in his cab without charge. He clocked in only a few minutes later than usual. At lunchtime, I tried the test run. It took less than half an hour to get to Dave’s apartment via streetcar and bus.

Dave’s place was quiet as a tomb, but the odor of mice struck me at once. It didn’t take long to set everything up and get the routines going. I noticed there were more mice now. From the logs, I knew Dave would be slaughtering this batch tonight. As I went over Dave’s surprisingly well-organized logs, I recognized where we were in the cell-culture cycle and cooked up a new batch of medium, acutely aware that I was using the last of the fetal calf serum. Lee called just as I finished refreshing the cell cultures.

“Just wanted to see if everything’s okay,” he said. “Is there anything you need?”

“We need fetal calf serum right away,” I answered. Lee asked me to spell it, and I did so. “I’m making a list and checking it twice,” he said.

“Okay,” I replied. Suddenly, Lee hung up. I realized it must have been necessary to break the connection quickly, because he didn’t say goodbye. I made copies of the new log entries and left for Dr. Sherman’s apartment. It took only ten minutes to get there from Dave’s, because I caught a bus right away. Okay, I thought: that’s the deadline bus. I have to hit that one right!

At Dr. Sherman’s apartment, the gardener noticed my arrival, so I stopped in the courtyard to chat with him. I showed him my key and told him I was interning with Dr. Sherman on an independent study, and that once or twice a week I had to drop off materials at her apartment, fill in her logbook, and use her microscopes to finish my reports. I was surprised when the gardener said Dr. Sherman had already told him I would be dropping by from time to time.

Dr. Sherman’s apartment was in perfect order. Of course, she didn’t have to put up with cages full of cancerous mice. After my duties, I caught a bus back to Reily’s, arriving there about 4:20.I had not taken time to eat lunch, so I was starving. I stopped at the Crescent City Garage next door, and spotted a vending machine that held a single row of cookies and crackers. I bought a small packet of Lorna Doones (my favorites) and went back to Reily to clock Lee out.

At five o’clock, I waited at the bus stop, hoping Lee would show up and ride home with me, but he didn’t, and I boarded the bus for home. I arrived tired and sad. The house was empty. Susie had gone to visit her children. Even Collie was gone. Robert was in the Gulf, and Lee was with Marina. I was lonely. I missed my sister, my Grandpa, my parents, and my friends back in Florida. I crawled into bed and crashed.

__________________________

1. There had already been deaths and crippling from a previous faulty batch of the Salk Vaccine. Dr. Ochsner’s own grandson had died from a bad dose of it, and Ochsner’s granddaughter had been stricken with polio due to another. The new oral vaccine had to be advertised as safer, even though it might cause cancer. Otherwise, all kinds of vaccines might be distrusted by the public.

2. The house was photographed in Jan. 2000 with Messrs. Shackelford, Platzman, and Riehl, with Anna Lewis and myself present, and was essentially the same, except the bathroom was finished, and closets had been added (everything was renovated by 2003, with even the front door moved to center: the house had been purchased, we were told, by a doctor from London).

3. Lee Oswald drew a sketch of my apartment and put it in his address book. What a shock, when I saw this page, after all those years! I thought that surely, that page would have been destroyed, as other pages are missing. Note two x’s where research materials were kept. Note single x on side of house (back right) where key was kept. Note that Lee started the sketch upside down, with the porch then, running out of space, he had to squash the back a bit. The owner’s daughter verified to three witnesses present with me that the tub was originally in the kitchen. Bathroom in front apartment was unfinished in 1963. I didn’t know Lee’s address book had been preserved until later, when researchers told me, therefore 60 Minutes never got this important piece of evidence. Lee’s address book is found in the Warren Commission documents.

4. On Robert’s birthday, I made certain that he got royal treatment: a blow-up ducky with a plaid bottom, a new shirt, and a pizza supper. We drank grape juice from two silver cups Robert brought with him. “Only the woman I will marry will drink with me from these cups,” he said. Such moments spin romantic dreams.

5. Monaghan would later slip the carbon copy (slightly different, but who cared?) into Retail Credit’s files. That way, if Lee had to change jobs later, he could use the background report on file at Retail Credit to serve as evidence of his ‘fine’ character.

6. The bus driver got to know us well. We later learned he was having an affair!