— CHAPTER 26 —

SILENCE

If I was going to live, I had to leave the past behind. But the emotional trauma I experienced watching the murder of the man I loved was devastating. It torpedoed my soul. Awash with feelings of hopelessness, I felt like the walking wounded staggering off a battlefield. The images of Lee getting shot played in my head over and over again. Each time, I could hear myself scream in the soundtrack, and thoughts of suicide flooded my head. I barely had the energy to fight them off. The joy had been sucked out of my life, and a cold shroud that I had never known before settled over me. What life? What was left of it? My promising medical career and my hope to cure cancer was reduced to ashes. The only man I ever truly loved was murdered before my eyes, and I could say nothing of what I knew.

I measured my loss repeatedly: there would be no more moonlit carriage rides, no glances between us as we walked together, I would never again gaze into Lee’s blue-grey eyes or hear him affectionately call me “Juduffki.” I gradually unpacked the suitcase under my bed; there would be no sudden departure to a new life of adventure. My life was now with Robert, a man who for weeks failed to notice my condition. Robert would never buy me begonias, nor yearn to read my poetry, nor would he want to climb Chichen-Itza with me. As I combed my hair, I remembered how Lee had caressed it, and could not bring myself to cut it. He had loved it long and free. In place of thoughts of suicide, I sank into an abyss of depression.

I could not share my situation with Robert. To his usual concerns about sex and saving money, a third was added: making good grades so he could quickly get into a Master’s program in geology. I easily convinced him to get this degree right where we were at the University of Florida, citing how expensive it would be to move to New Orleans. Of course I had no choice but to continue working as a lab assistant at PenChem, but I found myself without the will to continue my night classes at UF. I went to a doctor and he agreed that my health was pre carious: the university gave me “H” grades, allowing me to drop out of school for health reasons.

For the next five weeks, I struggled to hide my emotions from those around me. I did my best to follow familiar procedures in the lab, but was unable to concentrate on new material, and the quality of my work suffered. It mattered little: my boss had told me that my days at PenChem were numbered. I would be terminated as of December 31st.

Any mention of Lee’s name or the JFK assassination, even accidental encounters like news on the radio made my heart race. I made a conscious decision to guard what was left of my ability to conceal my heartache by refusing to watch, read or listen to any news on the subject. But it was impossible not to hear that they had blamed it all on Lee, and that they had identified his killer as Jack Ruby.

I knew there would not be an honest investigation. Powerful elements of the government were involved on too many fronts to allow that, and the American Media was steeped in a tradition of blind obedience to the government line. The American citizenry was likewise anaïve and unwitting accomplice. They would easily swallow the lie that Lee killed Kennedy in a solitary act of insanity.

I knew differently, but what could a college student do about it? Besides, I believed I would be murdered if I spoke out and, if I died, how would Lee’s children ever learn the truth about him? They had the right to know that their father had not killed Kennedy, that Lee had lost his own life trying to save the President. They needed to know that when Lee had a chance to flee and save himself, he stood his ground to protect them from retaliation by the monstrous forces he faced. These were my thoughts at the time and though I wasn’t there in Dallas that day, I will always believe in Lee’s innocence.

I realized that my work here on Earth was not yet finished, and resolved to go on with my life in hopes that one day I might be able to set the record straight, at least for Lee’s children. Lee would have wanted me to. But my emotions were still raw, my mood despondent, and each day remained a struggle: each smile an effort. December dragged on.

Dave Ferrie called me one last time, to deliver a message. He was adamant: we must never, ever, speak to each other again, for our own safety. He warned me that from now on, I must be “a vanilla girl. ” My maiden name must never appear in the newspapers. I was to keep my head down, and forget about being a science star. Forever! We were all in danger, and Santos Trafficante, the Mafia Godfather of Florida, would be watching.

“I’ve stuck my neck out by calling you, ” Dave said, at the end. “But Lee would have wanted me to. ” Then he said “Goodbye, J.”

He hung up. I listened to the silence and realized that my privileged contact with Lee’s underground maze was over. I was no longer part of their world and, if I kept my mouth shut, maybe they would stay out of mine.

On the final day of the year, I went to work at PenChem as usual. Mr. Mays, my supervisor, showed me the incomplete entries in my tearstained lab book, and reminded me not to return after the holiday.1

I entered 1964 depressed and unemployed, but at least I no longer wanted to kill myself. I retreated into painting, sitting in our decrepit little cottage, placing my dark thoughts on bleak canvases. Even Robert finally noticed. He told me to enroll in classes again, so I could see the university psychiatrist for free. When I did, I was diagnosed as suffering from depression. The doctor noted that it was a common symptom for girls on birth control pills. As a result, I was prescribed a lower dose. It was suggested that I take niacin, and I was told to stay in school, that the combination would eventually work. It did. Over the next several months, I slowly pulled out of my depression.

Robert graduated from UF at the end of the semester as an English major and immediately enrolled in UF’s new geology program to prepare for his role in the oil industry. For the next two years, we remained in Gainesville, and I continued to take classes when I could. I heard nothing from New Orleans and was completely unaware of the events that continued to unfold there, but at UF, there was a lot of talk about our involvement in a civil war in Vietnam, an obscure little country in Southeast Asia. In the election of 1964, with 80 percent public approval of his Vietnam policy, Johnson buried Goldwater in a landslide.

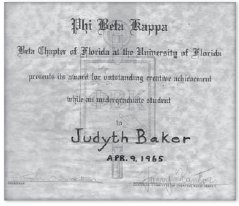

By 1965, my own work at UF was starting to shine again and my spirits were raised by an award for outstanding creative achievement from the Phi Beta Kappa Society. I also earned an Associate of Arts degree.

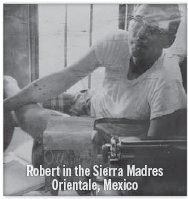

Late in 1965, Robert finished his M. S. in geology, and we moved to Austin, Texas where he continued in graduate school, working toward his PhD in geology and statistics. While Robert had little interest in foreign countries, Dr. A. F. Wedie, his director, wanted him to work on stratigraphy in Mexico for his dissertation. I encouraged the project and made sure I was able to accompany Robert there. We’d be living in the same country Lee and I had planned to explore together. In 1967 we moved to the Sierra Madres Orientale mountains in north-eastern Mexico where we had neither television nor English language newspapers. There I became pregnant and had my second miscarriage. Upon returning to the states, I became pregnant again. Since I had not yet had a successful pregnancy, the doctors feared I would have another miscarriage, so I was confined to bed a great deal. Even back in Austin we took no newspapers, nor did we have a TV set. I missed the news coverage of Jim Garrison’s investigation into Kennedy’s assassination. I was not even aware at the time that Garrison had arrested Clay Shaw and charged him with conspiring to murder the president. I certainly had no idea that his investigators were trying to identify me (the young woman seen with Lee Oswald in Jackson, Louisiana by two separate witnesses), or that my friend Anna Lewis had protected me by lying to Jim Garrison about knowing Lee.

Some have said that Anna’s bold lie saved my life, and I agree with that assessment. I should also mention that Mr. Monaghan (my boss at Reily’s) and Dean Andrews (Lee’s attorney), both of whom knew me, neglected to mention me in their Warren Commission testimonies. Whether they did this to protect me, others, or just to protect themselves, I cannot say, but I am glad they did.

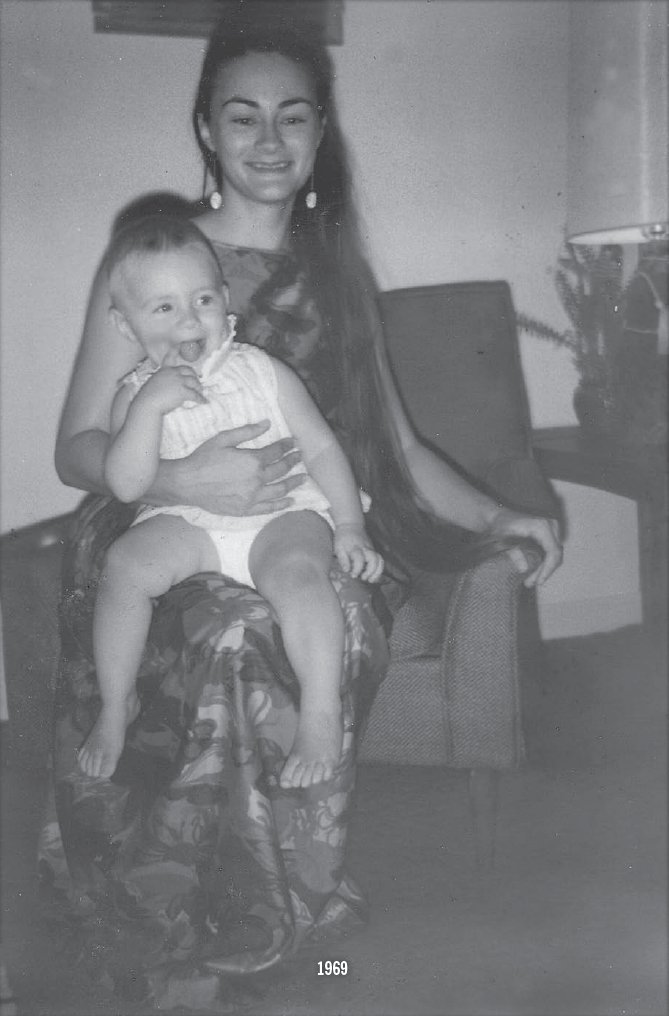

In mid-1968 we had our first child, a girl I named Susan (we always called her Susie). Susie was named after my dear friend Susie Hanover from 1032 Marengo Street. Ten days after Susie’s birth, Robert had to return to Mexico for another 10 weeks to finish his field work, so I went to his parents’ house on Santa Rosa Island in Florida. Though very elegant, the house was still under construction and it was a stressful time, especially having to deal with Robert’s stern mother, who believed that babies should “cry it out, ” and when she was home at night ordered me not to feed Susie until she stopped crying. I now understood why Robert was so unemotional, and this healed some of the distance between us. When Robert came back, I returned to Austin very grateful for his non-interference in child-raising.

Meanwhile, those who knew about the Project started dying off. On December 9, 1963 (only 17 days after JFK’s assassination) Mary Richardson died suddenly of a massive cardiac arrest, though she was still in her 40s. She was the preacher’s wife who had helped me that terrible night of the police raid in May of 1963. She had provided lunch for Lee and me and, while waiting for Lee to arrive, I had told her about Drs. Sherman and Ochsner. She had even driven Lee and me over to Susie Hanover’s house at 1032 Marengo Street. Mary Richardson was the only person outside the Project who knew the connection between the players. What did she do when she saw Lee arrested in Dallas? Did she contact the authorities to share what she knew? If so, was her death the price she paid for her honest intentions?

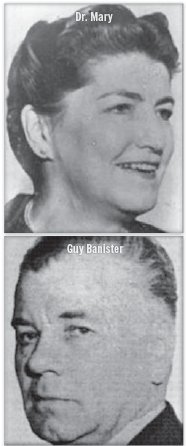

In July of 1964, Dr. Mary Sherman was brutally murdered. The true circumstances of her death were not released to the public. Guy Banister also died a few months later, and there is still some question about the cause. Banister’s pilot and partner, Hugh Ward, died in a mysterious plane crash. Sweet Susie Hanover disappeared, and we do not know what happened to her. Even Lee’s Uncle Dutz died that same year.

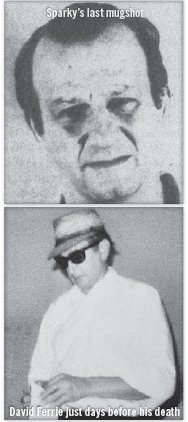

By the end of 1966, Jack Ruby was in Parkland Hospital dying of galloping lung cancer while awaiting re-trial outside of Dallas, but not before he told his jailer that he had been injected with cancer. Ruby’s sudden death on January 3, 1967 has always been considered suspicious by critics.2

David Ferrie also died under suspicious circumstances a month later, in February 1967, soon after it was announced that New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison was investigating him. Meanwhile, dozens of other witnesses, that I did not personally know, also died mysteriously, including Dallas County Deputy Sheriff Roger Craig who saw a rifle found in the Texas School Book Depository building that he insisted was different from the one reported to the Warren Commission. Then there was Lee Bowers, whose observations from the railroad control tower overlooking the parking lot atop the Grassy Knoll at Dealey Plaza contradicted the Warren Commission report

In 1969, Robert’s hard work and advanced education finally paid off. He got a job working as a petroleum geologist for Esso, now Exxon. We moved to Houston, Texas. Robert was making good money now, and our standard of living improved. He entered an exciting new world and traveled a lot, often speaking at professional conferences about his advanced work in computerized geology.3 In July, we finally bought a television set so we could watch the Moon landing.

Later that year, I had a remarkable personal experience that changed my life dramatically. One night, I had a dream in which Jesus appeared before me and, being disappointed with my sadness, let His pure love flood over me, forgiving me for everything in my past. It was amazing. Just like that, my faith was restored, and I was no longer an atheist. What a change! I was filled with a new sense of joy and a new purpose for my life. I had hope for our family, and began to look forward again. As it happened, Mormon missionaries knocked on our door. “Here’s a coincidence, ” I thought. I invited them in, and they soon persuaded me to join the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. Suddenly, a very large circle of new friends entered our life.

Robert was fascinated by my new friends and impressed by the dramatic change in my self-esteem. Soon he, too, joined the Latter-Day Saints in December 1969, which surprised even me, since he had been disinterested in religion since I’d known him. Robert proved to be flexible enough to join the LDS church, but there his flexibility ended. Once convinced, that was it: he would never leave the church.

As the 1960s ended, anti-war protests, psychedelic drugs, promiscuity, and bra-burnings still raged on in America’s youth culture. With my hatred for LBJ, I had written for underground newspapers under pseudonyms, and had even marched for peace, but there was so much work to do as Mormons that Robert and I were nearly overwhelmed.

We were welcomed, however, into a clean, ethical, conservative community that was family oriented, encouraged childbearing, and had plenty of love to share. No more birth control pills for me! Time to make babies. I felt my new Mormon community was the family I had lost, and I was back in the grace of God.

Our membership in this new religious community freed Robert to roam the planet helping Exxon obtain and develop oil wells, while I lived safely and securely in a bedroom community in Stafford, near Houston. Robert traveled to Australia, South America Malaysia and Norway, while my life was filled with hard work and fresh food. I was surrounded by dear friends, all of them pious Mormon women with burgeoning families. Yes, my new Mormon life isolated me from the outside world, but I was happy.

Strengthened by Robert’s professional success and our proud roles as new parents, Robert and I summoned the courage to visit our families at Christmas of 1972. Before going to Fort Walton Beach, we went to Bradenton. It had been ten years since my father tried to have me arrested when I left for college in 1962. The event had ruptured our relationship so badly that I had I boycotted family events. Besides, I was afraid to have my maiden name mentioned in any newspaper articles.

In 1964, Grandpa Whiting was in the VA hospital in Tampa again, and I was determined to visit him. When I entered his room, Grandpa lay there wheezing, staring at the ceiling. He was on so many painkillers that he scarcely recognized me. After we hugged, he asked me to check out the lumps under his arms. They were giving him radiation, and he was feeling horrible. “They still won’t tell me it’s cancer,” he said. “But you’ll tell me. “ It was so obvious. With tears in my eyes, I told him. “Hand me that damned rosary! ” he commanded. “I’ve got some work to do.” When I called my mother to tell her Grandpa was dying, she begged me to spend the night “at home.”

My sister was still not in college, and my parents had no intention of helping her to get there. When our parents started drinking, a fight ensued, and I took Lynda back with me to Gainesville. There, on November 24, 1964 — the anniversary of Lee’s death — overwhelmed with sorrow, I told my dear sister that I’d had an affair with a man I dearly loved, even though we were both married. I prayed she would not judge me.# She didn’t. Lynda married a wonderful guy who graduated from UF. Though I was thrilled for her, I didn’t dare attend her wedding in Orlando. By then, Grandpa Whiting was dead — I didn’t attend his funeral, either. And when my aged Grandparents Vary passed away, again, I was too afraid to go to their burials.

However, after nine years of being a “vanilla girl” and “keeping my head down” to avoid having either my maiden name or my connection to cancer research being reported in the press, I now believed it was safe enough to return to Bradenton. We arrived with little Susie and our baby son to see my parents, my sister and her husband, and my cousin Ronnie and his new wife. At last, a family Christmas!

But the legend of the girl from Manatee High School who wanted to cure cancer was still alive and well. On Dec. 28, 1972 an article appeared in the local newspaper, which began with “From the time she was a child, Judy Vary hated cancer.” Then it proceeded to summarize my scientific activities from “Magnesium from the Sea” to the American Cancer Society, to Roswell Park Cancer Institute, to the University of Florida. It went on to say that I was married to Robert A. Baker III from Fort Walton Beach, who was currently employed by Exxon Corporation in Houston, Texas, and that we were members of the Church of Latter Day Saints. It even listed the names and ages of our two children. Talk about blowing my cover! At least it did not mention New Orleans, or how my research career abruptly ended there. But ignorance was indeed bliss. I left town shortly before the article was published, unaware of its existence until researchers found it years later.

Fortunately, time does change some things: after J. Edgar Hoover died and his blackmail files had been destroyed, Congress finally investigated the intelligence operations of the CIA and the FBI. Senator Frank Church chaired the committee, and in 1975 he likened the CIA’s murder machine to a “rogue elephant stampeding out of control.” He described the FBI’s COINTELPRO program as “illegal and contrary to the Constitution.” The next year, as the United States celebrated its 200th birthday, the U S. Congress decided it was time to take a second look at the JFK Assassination, so they established the House Select Committee on Assassination (HSCA). The HSCA sought testimonies from anyone who might have information concerning the President’s assassination, but at that time I was deeply involved in the Stafford Bicentennial Commission’s activities. I was also busy having more babies and raising children, and not the least bit interested in exposing them to the darkness of an assassination, an extra-marital affair, and the horrors of a cancerous biological weapon.

Fearing the stress and attention which my testimony could generate, I decided to maintain my silence. Lee was still being blamed for Kennedy’s murder, and I understood that those who killed JFK could still easily eliminate me. I did not want my innocent children to become motherless.

Someday, I told myself, I will become brave enough to tell the world the truth about Lee, so that the children he adored will know what their father really stood for — but not yet. I was still too young and too frightened. So I did not step forward. (And, of course, nobody asked me to.)

Twelve years had passed since the JFK assassination, and some things were changing. The Warren Report had been dissected by experts, and its flaws were beginning to be chronicled and exposed. Jim Garrison’s trial of Clay Shaw had come and gone, and though it was soft pedaled and marginalized by the press, it inspired another generation of independent JFK assassination researchers to challenge the official version. But I knew nothing of any of that. All I saw was the mainstream media spin, which I still tried to avoid as much as possible. They had burrowed into their lies deeper than ever. I noticed that their language morphed in an Orwellian fashion: the words ‘accused assassin’ became ‘the assassin.’ The question “Did Oswald shoot Kennedy?” became “Did Oswald act alone? ” Outrage burned inside me, stoked by every accidental encounter with their deception. How could the truth be turned so upside-down? How perverse was it that a man who gave his life trying to prevent President Kennedy’s assassination would end up in history books as his lone killer?

No one knew what I knew. And only a few knew that I knew it. The only person capable of pulling down the Temple might be me. But if I did, that massive construct of lies could easily fall on me and my family. So I vowed never to buy a single book, nor bring home a thing that might crack my veneer of apathy concerning the subject. As far as my family was concerned, I would pretend that the nation’s sorrows did not touch me personally.

I ended up with five children, living in the safe Mormon world where I had respect and standing. I continued to avoid my past with the same tenacity I had used to block out pain in the hospital as child. I was afraid that if I looked into the face of that Medusa, I would lose control and reveal my dark secrets prematurely. I continued in this mode for years. As time went by, my fear of losing control of my emotions gradually abated, and the temptation to speak out grew less compelling. I had blocked it out of my life once again.

By 1977, I had made a kind of peace with my father. Then he suddenly died — on my birthday of all days — and I returned to Bradenton briefly for his funeral. I buried a lot of things that day: a new era of communication commenced with my mother and her family. She went on to re-marry a fine man and lived several more decades in comfort.

In 1980, we had a party at our house. It was a family-type affair with children and adults, and we were watching the Winter Olympics. We watched the hockey game between the US and USSR. There were about 35 people in the house, and the party was in full swing. The men were crowded around the TV set in our cavernous living room, and the game was getting quite intense. Amazingly, we were winning! Everyone was excited: I was busy serving snacks, when our thirsty 8-year son noticed that there were no more glasses in the cupboard. But he knew where there was one more glass. He headed to our tall bureau, climbed on a chair, opened one of the three vertical glass doors. When I saw him remove a large green tea glass, I called out, “Stop! Not that glass! That’s the one Lee Oswald gave me!” OOPS.

A handful of my Mormon female friends stopped their conversation and looked at me to ponder the curious comment. I gently removed the glass from my son’s hands and improvised, “Oh, didn’t I tell you? I used to work with Lee Harvey Oswald ... a long time ago, in New Orleans. We used to ride the buses and streetcars to work. He gave me this glass. It’s a keepsake.”

I quickly shifted their attention to cookies and the game, but the cat was out of the bag: from then on, I decided to occasionally tell a close friend that I owned such a glass so that no ‘mystery’ would seem to be attached to it. It became common knowledge in our family that I had known Lee Oswald in New Orleans, and he had given me the green tea glass that sat on the top shelf of the bureau.

By the early 1980’s, my faith in the Mormon Church started to fade, but not my faith in God. I had welcomed their control of my life, but I was concerned about their inordinate control over my children’s lives and their futures. I wanted them to have more freedom, and frankly, I was ready for some myself, so I began the long, difficult process of extraction.

Robert had recently been spending a lot of time in Norway and, in 1985, our entire family moved there. I met born-again Christians there (also in the oil industry) who helped me break my ties from the Mormon community, which was not nearly as strong in Norway as it had been in Texas. In 1986, about the time Susie left for college at BYU, I returned to Houston to finish my B. S. in anthropology. While there, I was baptized at Lakewood Church in Houston and officially left Mormonism after seventeen years. Robert, however, did not share my conversion, nor did four of my five children. He refused to read the letters I wrote explaining why I believed the LDS church was not for us. It triggered a show-down in our family. As a result, I took two of the kids and headed back to Houston. The other two stayed with their father in Norway.

Leaving the Mormon Church meant that I lost contact with hundreds of friends and the support structure I had grown to love. It was not only a personal loss, like losing a second family, but also a logistical loss, since I still had children to raise. I decided to move back to Bradenton to be near my mother and a beloved stepfather. I bought a house there and enrolled my children in schools near Manatee High School. Robert divorced me in November 1987, and only two months later married a woman recommended by the Mormon Church. Six months later, the two boys who had been living with their father and his new wife came to live with me. Lawsuits ensued and various legal battles dragged on for years, but I was determined that my children would have freedom to choose for themselves what religion they wished to embrace. I even drove them to Mormon services, if they wanted to go. With their father, there had been no freedom of choice.

As a well-compensated oil geologist, Robert had plenty of money for the custody battle. But I spent every cent I had fighting to keep the four children: I eventually lost our house in the process. In the end, my lawyers were so disgusted with Robert’s tactics that they worked for free.

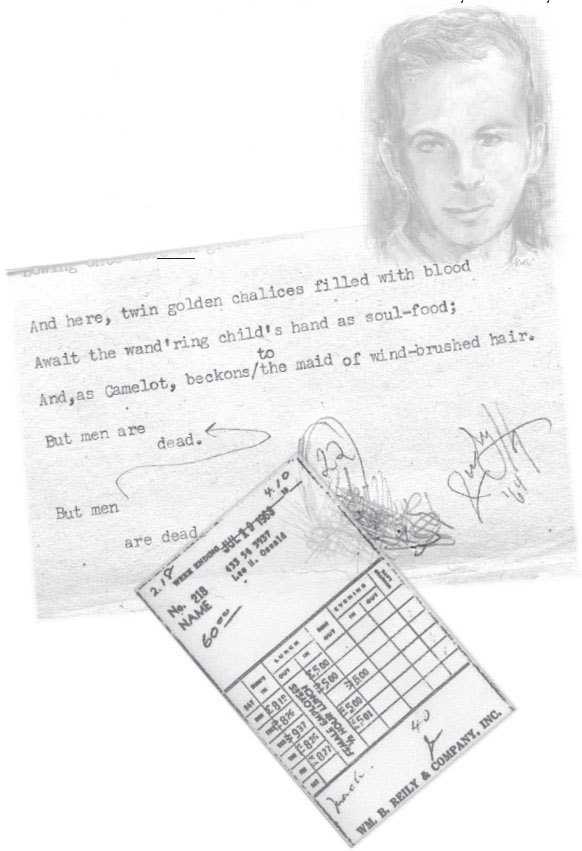

During the years with Robert, I had avoided anything to do with the JFK assassination, but once he was gone, I gave myself permission to quietly remember what had happened back in 1963. So in November 1987, on the anniversary of the assassination, I got out the green glass and the black necklace that Lee had given me years before, and let myself start remembering again. I got out the newspaper clippings, photographs, and documents from my youth, leafing through them for the first time since 1963. My children had never seen any of these items. To this day, most of them still haven’t.

I re-read the articles about the girl who dreamed of finding a cure for cancer. And, yes, I cried. The old wound was open once again, and I felt it was finally time to face it. From that day forward, at the end of each November, I would write memory-jogging items on small sheets of paper: our conversations, the sights and the sounds, the little things that Lee had said to me. I recalled the day I was banished from cancer research by Dr. Ochsner, and Lee encouraged me to “uplift hearts instead of bodies” and to “create beauty” with my paintings. Confronting the shortness of his own life, Lee said “Now, I’ll never have the time to read and learn everything I want to.” I asked him not to talk like that, adding: “You’re not dead until you’re dead.” “Ah, Juduffki,” Lee answered, “there are walking dead all around us.”

Eventually, I organized my collection of documents into 3-ring binders. But I still did not talk to my children about any of this. These were my personal secrets. I kept them to myself. I wanted to protect my children from them, at least while they were young.

As the 1980s ended and the 90s began, my children worked hard to get to college without any help from their father: every one of them would win full scholarships and many awards. I was very proud of them and, though I was stretched thin with full-time jobs and single parenthood, I made special efforts to help them have some fun on weekends.

On Saturday nights, my living room was full of teenagers piled on pillows and sofas watching videos. The kids would rent a popular video of their choice from the local store and bring it home. They would watch the movie, while I served snacks and kept a cheery eye on the proceedings. I was teaching and counseling at that time, and all the kids felt at ease with me. Besides, this was the only chance I had to see movies!

One Saturday night in 1992, it was time for our movie party. My oldest son was home from college between semesters, and was responsible for selecting the movies that night. Our only rule was that it not be something grossly inappropriate. The kids arrived, and once everyone settled into their spots, the movie began. Busy at the back of the room preparing treats, I kept one eye on the screen to see what they were watching. I heard a familiar but dated voice announcing something like a news broadcast, and I looked at the screen to see the initials “JFK” appear in white letters on a black background. It was Oliver Stone’s film! With a sinking heart, I realized I couldn’t handle it. Not in a room full of teenagers! Without saying a word, I got up and called a neighbor, asking her to keep an eye on our house and kids. Something had come up — I needed to leave. I got in my car and drove to my church, where I prayed for strength.

A few hours later, I returned to a room full of curious teens who wondered where I had gone. I dodged their questions: I was not ready to talk about it.

As a result of Oliver Stone’s film, the U. S. Congress passed the Assassination Records Act and set up the Assassination Records Review Board (ARRB) to de-classify many of the surviving documents surrounding the JFK assassination, as well as to collect additional testimony from anyone who had relevant information. But I was still in the middle of a bitter legal battle with my ex-husband. Can you imagine the impact on a custody fight that stepping forward and telling the ARRB my story would have had? I didn’t dare speak up. I still had precious children to raise, and until they were out of the house and on their own, I had to maintain my silence.

By 1994 I lost my house, and my youngest child and I moved to Orlando where two of my sons attended college. I returned to college myself, and in 1996 earned an M.A. in English. Later that year, I was offered a fellowship at the University of Southwestern Louisiana and moved to Lafayette, Louisiana with my youngest daughter to work on my Doctorate. In a wave of nostalgia, I had applied there with the idea of living in the same state where Lee had been born. For the next several years, I taught college classes. By 1998, I had completed all my advanced courses in writing, 18th Century Literature, and linguistics and would soon pass all my comps. I became what academics call ABD: All But Dissertation.

In December 1998, my youngest daughter married and went on her honeymoon. Finally, I was alone. The next day I rented JFK and sat down to watch it in earnest. Needless to say, watching Joe Pesci’s dramatic portrayal of Dave Ferrie and Gary Oldman’s amazing depiction of Lee was a surreal experience for me. It was like watching a dream, but knowing you were not asleep. I noticed funny things, like Joe Pesci’s voice had a higher pitch than Dave’s, and Lee didn’t stutter as much as Gary Oldman showed him doing, but beyond such trivia, it was a fairly good re-creation of the world Lee and I had known. I was amazed that it was acted mostly by people who had never met Lee, Guy Banister, or Dave Ferrie.

But what struck me most deeply that day was the inscription at the beginning of the film. The words were seared into my brain:

“To lie by silence when we should protest makes cowards of men.”

I knew that I had been “lying by silence.” If I did not speak up, then I was a coward. Could I tell my children that we were all cowards — that there are no heroes left? It was a watershed moment. I soon began writing a detailed chronology of everything I could remember in a series of letters to my oldest son. Letters that I had no intention of giving him: he might find them after my death. I still planned to go to my grave without saying a word out loud. Still, it was a small step forward.

It had been 35 years since 1963. Hundreds of books had been published, with a wide range of theories. I didn’t know the names of any of them, but it was time to start learning what people had been told about both Lee and the JFK assassination. So I read two books that I found in the city library: Oswald’s Tale and Marina and Lee. I was shocked at the lies and distortions about Lee, but there was an even bigger shock when I learned who Jack Ruby really was.

He was not just the man who had murdered Lee. His real name was Jacob Rubenstein, and in his youth, his old mob buddies from Chicago called him “Sparky” because of his short temper. Jack Ruby was “Sparky” Rubenstein! Lee’s friend! The man whom I had met at Dave Ferrie’s apartment in New Orleans! Could life really be this perverse? It was Sparky who told me that he had known Lee since he was a child. It was Sparky who had given me a $50 bill as an apology for losing my rent due to the police raid at Mrs. Webber’s boarding house. It was Sparky who had taken us to dinner at Antoine’s (and to Clay Shaw’s house) the night that Lee saved us from the menacing sailor. And it was Sparky who had hosted our evening at the 500 Club with Carlos Marcello. Sparky was Carlos Marcello’s friend Jack Ruby — the one the strippers at the YWCA told me about! And it was Sparky who had marched into the basement of the Dallas Police Station, pulled out his 38 caliber pistol and killed Lee.

When I realized Lee had been murdered by a friend he had known since he was a child, my eyes were opened to the corruption that rules our nation. I recalled that in his last phone call to me, Dave had tried to explain why Jack Ruby had to kill Lee — that Lee would have been tortured to extract a confession, or they would kill him in the attempt, once they got him out of the public eye. Dave had forgotten that neither he nor Lee had ever told me Sparky’s current name. Dave had tried to convince me that Lee’s murder was a mercy killing. He wanted me to accept that, so I wouldn’t tell anybody what I knew about Lee’s killer, and his knowledge of the project. Of course, I never did. Learning that Jack Ruby had died of cancer while awaiting re-trial, perhaps even due to the same cancerous bio-weapon that Lee and I helped develop, gave me no satisfaction. No one deserves to die like that. But having heard Dave Ferrie tell Jack Ruby about our cancer project, I knew that Ruby was fully aware of its potential, and in fact, he was probably supplying money for it. With that in mind, I found it very interesting that Ruby died 28 days after being diagnosed with cancer, just as the prisoner in Jackson had done, and that shortly before he died, Ruby told family and friends, “I have been injected with cancer cells.”

The hour had come. I wanted to remember it all. Record it all. Leave my memoirs for my children, and for Lee’s. I called my sister and asked her to go with me to New Orleans. After more than 35 years I was ready to go back and confront what had happened. With our friend Debbee in tow, we headed to New Orleans to visit the places burned into my brain by the events I lived through. When we did, I had vivid and painful flashbacks. Some were overwhelming. At one point, when we were riding on a streetcar down St. Charles Ave., I was suddenly overcome and burst into tears. I began sobbing hysterically and got off the streetcar, followed by a puzzled and worried sister and friend. It terrified me to realize how much pain was still locked inside. Now I knew that the very act of speaking up would be difficult for me emotionally. Would I break down and start crying in the middle of interviews? Could I maintain my composure enough to get my story out?

Nevertheless, I was determined to break my silence. But, how? Where do you go to tell a story like mine? And to whom?

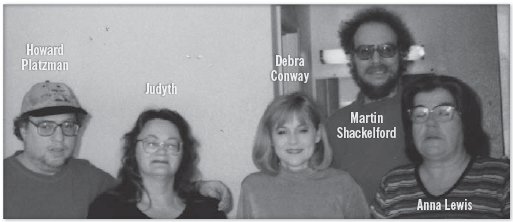

In 1999, I contacted a TV documentary program and they asked producers at 60 Minutes to interview me. While these telephone interviews were being conducted, I obtained a literary agent and gave him a teaser book, for I was afraid of who might sue me or try to hurt me. I told him that later I’d give more information. With my daughter gone, I was able to get more access to the Internet and I decided to find people within the JFK research community who might help me present my story to researchers, publishers and the press. I observed that Dr. Howard Platzman and Martin Shackelford were not “anti-Oswald” as were most on the newsgroup I was reading about. I contacted Dr. Platzman, who worked for an insurance company in New York City. By this time I had found several witnesses, a few of whom consented to be taped or filmed. Among them was Anna Lewis: her husband, David, had died of cancer. I was pleased to learn that she had told her family about having known Lee and “his friends” for years.4 When I told Platzman and Shackelford about how Lee and I had double-dated with Anna and David Lewis, we decided to meet in January, 2000, so they could meet Anna Lewis face to face, along with Dr. Joseph Riehl. I regret that I did not share as much information with Dr. Riehl as I should have – he was my dissertation director at the time, and I was too fearful of conflicts of interest. He did offer a shoulder to cry on!

By then, I had confirmed much of what Edward Haslam had written about the secret labs and the Project – I had learned of Haslam’s little-known book, Mary, Ferrie, & the Monkey Virus, late in 1999 and obtained a copy in November. I was amazed how Haslam had ferreted out so much that I thought had been buried forever, out of reach.

Dr. Platzman invited Debra Conway, who was an executive with JFK Lancer (they run conferences and sell books about the JFK assassination) to attend our January meeting in New Orleans. She and Shackelford brought their video cameras. I hadn’t been aware that any filming would be conducted, and thought we were simply going to have interviews and then do a tour of the various sites.

By then 60 Minutes had hired Dr. Platzman and others to investigate my story, which they did for 14 months. Everyone’s expectations were high. 60 Minutes had the ability to get the story into millions of households in a single day. They interviewed me repeatedly in New York and elsewhere, as their investigators scoured the National Archives to find evidence that might support my story. They paid expenses for me and two investigators to visit New Orleans, but unfortunately one of them was Brian Duffy: he had written glowing reports about Gerald Posner’s Case Closed. He said it was too hot to tour the city as I wished, stayed in the shade and went nowhere, as did the trip to New Orleans. In 2001, after three promises that the story would be aired, 60 Minutes backed out. What a disappointment! A few weeks later, I saw an email from Phil Scheffler, one of the producers, who said that their investigation into my story was the “longest and most expensive investigation” ever conducted in the history of 60 Minutes. Respected producer Don Hewitt, who created 60 Minutes, sent me an apology.

Not airing the story must have been a grave decision after making such an investment. When C-Span asked Don Hewitt about their decision a year later, he said, “[We] were convinced that we were about to break the biggest story of our times... but the door was slammed in our face.”

For the next few years, I struggled to tell my story and earn a living. I was having difficulty holding a job because my name was now out there on the Internet, with websites telling lies about me. Several times I was fired from a teaching position due to being ‘notorious.’

One incident that was both a success and a set-back occurred in 2003. As the 40th anniversary of the Kennedy assassination approached, I was contacted by Nigel Turner, a British film and television producer who had developed a well-respected series called The Men Who Killed Kennedy, The six episodes had become a fixture on the A&E’s History Channel and were shown several times a year, but with special emphasis each November. Turner was planning to add two new episodes when Gerry Hemming, whom I had visited, told Turner about me. Turner looked into my past and then interviewed me for days. In the end, he asked the History Channel to allow him to make a third new episode about my relationship with Lee.

After interviewing me on tape, comparing that with his notes, and doing more research, Nigel came to my house in Orlando again and interviewed me on camera for 38 hours over the next several days. The result was reduced to a 46-minute-long segment called “The Love Affair” that aired five times, along with his two other segments (“The Smoking Guns” and “The Guilty Men”) on the History Channel in November, 2003.

The show was extremely successful and over 50,000 copies of its DVD were sold by the History Channel the following week. However, one of the two episodes that had accompanied “The Love Affair” had made the unambiguous claim that then Vice-President Lyndon B. Johnson had cooperated in the assassination of President Kennedy. Though Johnson was dead, his wife was alive, wealthy, and angry. She and other LBJ supporters, including two former Presidents, Jack Valenti (President of the Motion Picture Association of America) and Disney’s distributors, attacked the History Channel with threats of law suits. All three new episodes were hastily withdrawn and the masters were supposedly destroyed, though there was no specific allegation about the content of “The Love Affair” itself. Yes, this was a major disappointment but, fortunately, irrepressible renegades have repeatedly posted videos of the episode on the internet to get the story out. The History Channel has never aired it again.

Frustrated, I tried to communicate my story on the Internet. What a disappointing experience that was! I figured that anti-conspiracy opponents who believed that Lee had killed Kennedy would argue with me, but I did not anticipate that they would resort to rude, personal attacks in an effort to discredit me... or drive me away. Yes, it hurt. But they only drove me away from their websites, not from my goal of getting the truth out about Lee. But what really surprised me was the volatile reaction of many pro-conspiracy JFK researchers, some of who were heavily invested in their own theories (and in their book sales). New eyewitness testimony of Lee Oswald’s involvement in a bio-weapon project forced them to rethink everything and challenged their views. I learned, rather late in the game, that such people can say almost anything on the Internet without having to back up their accusations with hard facts. One researcher claimed I changed my family name from ‘Avary’to ‘Vary’ because I did not like my family name. Another one solemnly declared that I had been diagnosed with a mental illness by a psychologist friend (who had never met me). I learned that the groups and forums on the internet, whether pro-conspiracy or anti-conspiracy, were basically fan clubs led by a handful of leaders who wished to promote their books, theories and personal beliefs. They like to argue and want to win. It’s a sport for them. If they ‘like’ a new witness, who fits their theories, all is well. If they don’t like you, watch out.

Along the way, however, I made some good contacts with JFK researchers like Pamela Brown, who has simply kept reminding people to consider my story without preconceptions. Jim Marrs interviewed me in person and on camera on several occasions, as have more iconoclastic researchers with open minds such as Dr. Jim Fetzer, Wim Dankbaar, and Harrison Livingstone. Peter Devries, the Dutch investigator who uncovers frauds and criminals, has also filmed me as a witness after investigating me. These people took the time to study the evidence and then embraced my story. I also met other witnesses (e. g., Gerry Patrick Hemming and Dan Marvin) who had worked in Lee’s covert world themselves and understood its rules and rhythms. But it was 60 Minutes that introduced me to author Edward Haslam, who had been doing his ground-breaking research into the death of Dr. Mary Sherman and her connections to David Ferrie and his cancer research project for over a decade before I met him.

Haslam studied my documents in detail and interviewed me extensively and repeatedly (in person, on the phone, and by email) before deciding to include my story in his 2007 book Dr. Mary’s Monkey, which helped people to understand the players (like Dr. Ochsner) and issues (like anti-Communism) behind our bio-weapon project in New Orleans.5

Today, convincing evidence continues to emerge that is exonerating Lee from the lies of 1963 and beyond. First, we know that Lee could not have killed Dallas Police officer Tippit, which is what he was originally arrested for. At the time Tippit was shot, Lee was already sitting in the Texas Theatre, which is where the police arrested him minutes later. Further, the shells found at the scene of the Tippit murder had been fired from a semi-automatic pistol, not a revolver like the one the police said they wrestled away from Lee in the theatre that day.

Second, Lee could not have shot President Kennedy, because witnesses saw Lee on the second floor of the Texas School Book Depository moments before and after President Kennedy was shot. Lee was seen in the second floor lunch-room, where he bought a coke from a vending machine, not on the six floor as has been claimed. If there were multiple snipers on the sixth floor, as some have claimed, Lee was not one of them.

Third, Doug Horne, a former military intelligence analyst who worked on the staff of the Assassination Record’s Review Board (ARRB), published a comprehensive five-volume series entitled Inside the ARRB, which presents evidence to support his conclusion that the U. S. Government’s evidence (including the x-rays and medical evidence) was tampered with and falsified. In the process, Horne revealed that critical frames from the Zapruder film, which showed the exact moment Kennedy had been shot, had also been altered to hide visible damage to the back of Kennedy’s head – damage caused by a bullet from the front. Extremely high resolution blow-ups of these frames, presented to Horne by Sydney Wilkinson, whose team of professional film restoration experts (“The Hollywood Seven”) found evidence of gross tampering in the Zapruder film, including the fact that the back of Kennedy’s head had been crudely painted black to hide a shot from the front. As Sydney told me herself on the phone, “He didn’t do it, Judy! This proves it!”

And finally, in his well-researched and powerfully written book, JFK and the Unspeakable, author James Douglass explains why powerful forces inside the U. S. Government decided to kill JFK. Before looking at the event itself, he establishes the context of the assassination. In the process of tracing the story step-by-step, he reveals that a plot to assassinate Kennedy in Chicago on November 2, 1963, had been foiled thanks to a tip from an informant named “Lee.” Douglass poses the question: Was this “Lee” really Lee Harvey Oswald? Suddenly, I understood the cryptic comments that Lee had made to me in October about getting a “trusted FBI contact” in Chicago from Dr. Mary Sherman. If Lee had not warned them about Chicago — and if Kennedy had been killed in Chicago on November 2 — then he would never have come to Dallas. Lee would never have been accused of assassinating him, nor been murdered himself. Due to Lee’s heroic actions, Kennedy lived three extra weeks, and Lee died as a result. Such was the cost of his courage.

I have paid my own price for speaking up. Not only have I been subjected to rude insults and conspicuous harassment on the internet, I have experienced mysterious car crashes that appear to have been efforts to discourage me from telling the world what I know. I have experienced death threats so terrifying that I applied for political asylum in a Scandinavian county; while under their protection, I had to miss my own mother’s funeral. For my own safety, I now live outside the United States year-round, and members of my own family have disowned me. I’m only in touch with two of my children now, and I haven’t seen any of my seven grandchildren for years. One son, who now refuses to speak to me, asked me to publish my story as “historical fiction.” I refused. This story is true, and I have told it as accurately as I can.

Now I leave my testimony in your hands.

Judyth Vary Baker

__________________________

I placed a little note inside the green glass, where it sat for many years next to Lee’s handwritten “receipt.” The note explained where my evidence files were hidden, with instructions to take the files to our family attorney in case I was found dead. My sister wrote a long letter describing what I told her:

Subj: memories Date: 05/16/2000 1:29:29 AM Central Daylight Time From: bxxxxxxx) To: electlady63@aol.com (Judyth V. Baker) Dear Judy, I am sorry for not writing you sooner, but with my new job and school, it has been quite hectic. I don’t need to tell you about hectic because I think you wrote the book on that already. Speaking of books, I told you I would write to you about what we shared in conversations many years ago... I believe in the fall of 1964 when I lived with you and Bob in Flavette at U of F. I remember on one particular evening, we were reminiscing about our past and what we hoped would be in our future lives, and that was the night when our conversation turned to even more serious talk about you. I remember we stayed up very late, and you were quite concerned about whether or not you should tell me something so serious in nature that you weren’t sure if we should continue our discussion. But, you know me, I egged you on to tell me what was so important that you couldn’t share it with me. I remember you told me that if I wanted to know what you were keeping to yourself, I had to swear to secrecy and never tell anyone about this. You said if anything ever happened to you.... such as an early or premature death, then I should tell anyone that would listen about what you were about to tell me. I swore to you I would keep your secret, and up until this day I have done that. Now, because of the writing of your book, and with your permission, I will repeat what you told me so many years ago. You told me you were afraid for my well-being, but felt I needed to know what had transpired in your life at that time. Here goes.....You told me that you had a love affair with a man who was trying to help our country and he was involved in very secret and covert activities for our country. You said you met him when Bobby left you all alone after you were married and you fell in love with each other. You told me if anything ever happened to you, I was to look for a green glass that he had given you as proof of what you were telling me. You said that my life might be in danger if I ever mentioned this to anyone and made me promise that I would never speak of this conversation again unless something happened to you. I was full of questions, and you were very hesitant to give me many details, other than you and he had shared a common interest in saving our country and the President, and that you were both very much in love. You said you wanted to be buried next to him some day, and someday you would tell me the whole story about the two of you. You said you worked closely together and had some close friends who were also working with you. You said the friends were also in danger and you wouldn’t tell me much more. You said someday I would know everything, but it would mean you probably would not be alive if that knowledge came to me. I remember I was frightened for you and didn’t understand what it was all about, but I also knew you were in pain and hurting over this man you loved so much. You reminded me about the green glass several more times during our conversation that night, and wanted me not to think badly of you for being in love with another man when you were already married to Bobby. I told you I would never judge you, Judy, and I never have. I have kept this secret all these years, including how you and he had loved each other so much and how you wanted to be buried next to him when you die. I now know why you wanted to protect me and not tell me the details of you and Lee... and I also know why you feared for your life for all of these years and wanted to protect me and your children from any danger. I know what you told me was the truth back then, and I still remember the fear and at the same time the love in your voice when you told me this information. I hope people will believe you and me as well, because I swear what I have just written is true. I love you honey, with all of my heart. Your sister, Lynda

1. Mr. Mays said I had erased some data and changed it. But only ink-written data was permanent. Data written in pencil was double-checked, then re-written in ink.

2. Jack Ruby’s death on January 3, 1967 has been considered suspicious since the day it happened. The main suspicion has always been that Ruby had been injected with cancer to prevent him from speaking more freely about what he knew during his upcoming re-trail outside of Dallas. Many discounted this claim since giving somebody cancer by an injection was not considered to be medically possible at the time. In his book, CROSSFIRE, Jim Marrs addresses “The Mysterious Death of Jack Ruby” (p.429) and notes that on October 5, 1966 the Texas Court of Appeals overturned Jack Ruby’s conviction and on December 7, 1966 ordered a new trial to be held outside of Dallas. Two days later, Ruby became ill and entered Parkland Hospital where doctors initially thought he had pneumonia, but quickly changed their diagnosis to lung cancer. Before the week was over, the Parkland doctors announced that Ruby’s lung cancer had advanced so far that it could not be treated (meaning it had spread to other parts of the body — Stage IV). The median survival time of a patient with Stage IV lung cancer is eight months, but twenty-seven days after the onset of his initial symptoms of cough and nausea, Jack Ruby was dead. Deputy Sheriff Al Maddox was Ruby’s jailer at the time. He later told researchers that Jack Ruby told him of being injected with cancer and handed him a note making that claim. Maddox also remembered what he described as a “phony doctor” had visited Ruby shortly before he became sick. A second law enforcement officer said Ruby had been placed in an x-ray room for about 15 minutes with the x-ray machine running constantly, an action that would have certainly compromised his immune system. The autopsy found the main concentration of cancer cells to be in Ruby’s right lung, but noted that cancer cells had spread throughout his body. These cells were sent to nearby Southwest Medical School for closer scrutiny using an electron microscope. Bruce McCarty, the electron microscope operator that examined Ruby’s cells there, told Jim Marrs that he was surprised to find Ruby’s cells had microvilli (tentacle-like extensions that grow out of the main cell), since microvilli were not normally seen in lung cancers. A decade later, however, cancer researchers at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York noted that when cancer cells of various types and origins were suspended in specialized liquids they would form microvilli extensions “when settling on glass.” This is consistent with my description of the need to separate their suspended cancer cells from the sides of the glass thermos every couple of days.

3. Robert A. Baker III of Stafford, Texas was awarded at least five patents by the U.S. Patent Office for his innovations in seismic science during his career. They were: US Pat. 6014344 - Method For Enhancing Seismic Data, US Pat. 7013218 - System And Method For Interpreting Repeated Surfaces, US Pat. 12041767 - Method For Editing Gridded Surfaces, US Pat. 6775620 - Method Of Locating A Surface In A Three Dimensional Volume Of Seismic Data, and US Pat. 6675102 - Method Of Processing Seismic Geophysical Data To Produce Time, Structure, Volumes. He also invented numerous patented processes that are held solely by Exxon Corp.

4. David Lewis said he had seen Banister, Ferrie and Lee together in 1962. People assume Lee never left the Dallas-Fort Worth area in 1962 after returning from the USSR, but he was estranged from Marina for weeks at a time, and his whereabouts are mostly unknown. Anna Lewis stated she remembered seeing Lee in the fall of 1962. These people were not lying: Lee told me in April ‘63 that he had recently been in Florida. From New Orleans, Lee flew to Texas and reputable witness Antonio Veciana told HSCA investigator Gaeton Fonzi that he met Oswald there at a time when Marina insisted her husband never left town.

In a debate between Jim DiEugenio and John McAdams on Black Op Radio it was stated, “You get people like David Lewis, who absolutely insisted he saw Oswald with Ferrie and Banister, but he insisted it was in 1962 — well, that was shot out of the water.” No, it was “shot out of the water” only for those who refuse to consider the eye-witness testimony of David Lewis, Anna Lewis, Judyth Baker and Antonio Veciana.

5. When I first talked to Edward T. Haslam he told me he had met a woman in New Orleans in 1972 who said her name was Judyth Vary Baker, and that she had been a close friend of Lee Oswald. Whoever this woman was, it was not me. Once we met, and he saw I was not the same woman, Haslam accepted that someone had gone to the trouble of presenting him with a double in an attempt to mislead him and discredit me.