FOREWORD

A quick look at the cover of Me & Lee will tell you this is an autobiographical book about a young woman named Judyth Vary Baker and her relationship with Lee Harvey Oswald in New Orleans in 1963. Lee was the 24-year-old man who burst upon the national stage faster than any person in American history. On November 22, 1963, his unknown name was transformed into a household phrase in a matter of hours, when he was publicly accused of murdering President John F. Kennedy.

President Kennedy had been gunned down by sniper fire in Dallas as his motorcade passed in front of the building where Lee worked. Denied his lawful right to an attorney, Lee Oswald vehemently denied committing the crime at every opportunity. In his words, “No, sir, I didn’t shoot anybody.” He then asked for legal representation.

Two days later, Lee was written into the history books himself for something he could not deny. He became the first person ever murdered on live television. The nation watched helplessly as Oswald was shot down before their eyes, while handcuffed and paraded through the basement of the Dallas police station. America heard the blast of Jack Ruby’s .38 caliber pistol as he shot Lee Oswald at point-blank range, but we did not hear the screams of the 20 year-old girl watching from her television set in Gainesville, Florida – screams that echo throughout the pages of this book.

The narrative starts with that same young girl in Florida and drives patiently, but relentlessly, toward that infamous weekend in Dallas; a weekend that changed history. It would be reasonable to read such a story to gain new insights into what role Lee Harvey Oswald actually played in those events. This much you can expect. What is unexpected is the realization that you might have wound up reading a biography of Judyth Vary Baker even if she had never met Lee Oswald, but for a completely different set of reasons.

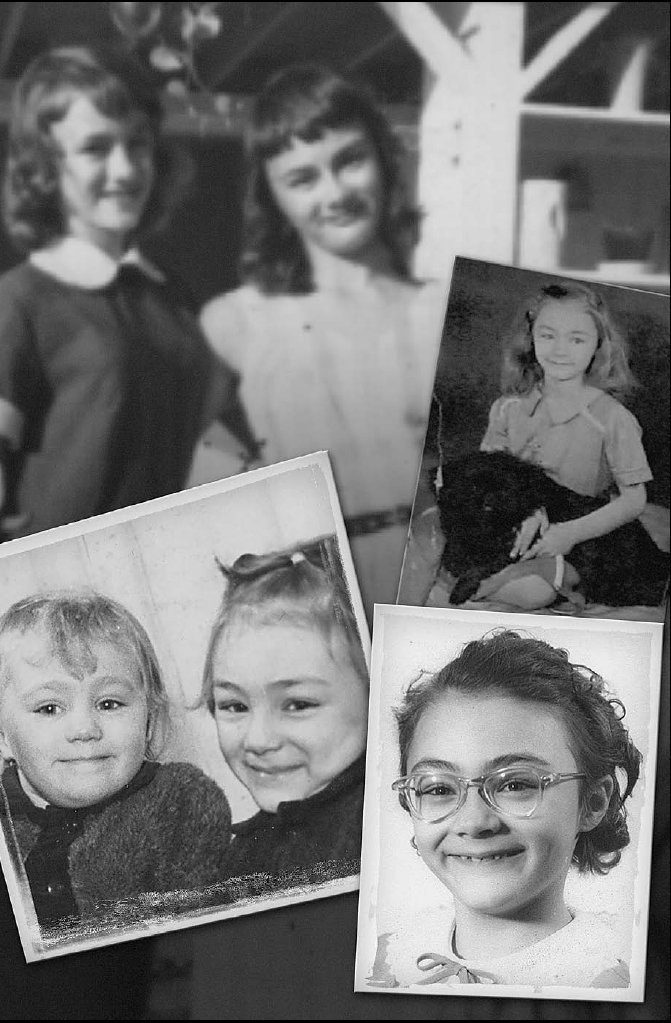

Here is an unusual tale about a remarkably talented young woman who used her unique combination of brains, beauty, personality, and determination to chase her dream of finding a cure for cancer. The astonishing thing is how successful she was in that effort, particularly at such a young age. Considered a scientific superstar by the press in her home town, and recognized for winning awards at prestigious science competitions, Judyth achieved prodigious feats while still in high school. These accomplishments attracted the attention of America’s top scientists and some of the nation’s most powerful political figures. Universities sent her offers. Scholarships were handed to her by prominent organizations. Newspaper articles enthusiastically praised her efforts to fight cancer and promoted her dream of finding a cure. All of this happened before she met Lee Oswald. In fact, the name Lee Harvey Oswald is not even mentioned in the first five absorbing chapters.

The fateful summer of 1963 in New Orleans derailed her life and cast her future into obscurity with the same vengeance that Oswald’s name was cast into infamy. Fearing that she would be murdered, just as her friend Lee had been, she kept silent for decades. Warned that she would not be allowed to continue in the world of cancer research, she dropped out of science and abandoned her dream of finding a cure for cancer.

Instead she had five children and educated them to her own high standards. So, we are left to ponder the question: Would Judyth Vary Baker have found the cure for cancer if she had not been derailed? Or with her help, would we at least have a better weapon to fight the cancer epidemic that we face today? Is this omission part of the price we collectively pay for the subterfuge of the 1960s?

Like most biographies that are worth reading, this one presents a flawed hero who was exquisitely human. Judyth was an ambitious selfpromoter who was both naïve and, at times, reckless. And she is full of contradictions: she loved animals, but killed hundreds of them by giving them cancer in her laboratory. Spoiled by her own success and cursed with questionable judgment, she zigged and zagged through life, running towards the things she loved and away from the things she loathed. She lunged from extreme to extreme with passion and conviction: From being an 18 year-old virgin who dreamed of becoming a nun, to committing adultery with a man who left a pregnant wife and baby alone at home in order to embrace her. What triggered her downfall, however, was not the fact that she strayed from her morality, but that she returned to it at an inconvenient moment. The problem was: She objected to intentionally killing a group of “human volunteers” in order to test the biological weapon which she and Lee had helped develop. In doing so, she endangered the reputation of a famous doctor - a sin that the doctor was not willing to forgive. Consequently, he banished her from medicine forever.

This is not a romance novel. It is a piece of history; a tile in our national mosaic that, once illuminated, changes the color of everything around it. It is the real-life story of a young girl trying to succeed in life. Trying to make her contribution. Trying to do something patriotic and important. Judyth Vary Baker is a witness, not a researcher.

Her tragic tale is an emotional odyssey told in the first person, but it is one with enormous political consequences. It shakes the very foundation of the explanations offered to the American people by their own government concerning the assassination of President Kennedy. Needless to say, getting her story out to the public has proven to be a long and difficult road. It presents new information which challenges the understanding of these important events. New information that is inconvenient for critics, historians and pundits, all of whom are vested in their own interpretations of these same events.

I was introduced to Judyth Vary Baker in 2000 by the staff of 60 Minutes, the CBS News television program. I had written about the underground medical laboratory in New Orleans in which Judyth told them she had worked back in 1963. 60 Minutes researched her story at their expense for 14 months, and their Executive Producer Don Hewitt called it “the biggest story of our times.” So I was disappointed when 60 Minutes decided not to air it. But I was interested in Judyth Vary Baker for my own reasons and subsequently arranged to meet with her in person. When we did, she allowed me to examine the volumes of evidence that she had organized into 3-ring binders. She was the witness that I had been missing in my investigation. She was “the technician” that I had predicted would have been necessary for the covert cancer laboratory that I had heard rumors of in the 1960s. A technician that had been trained to handle cancer-causing viruses.

I stayed in contact with Judyth over the years by phone and email. For the next nine years, I witnessed first-hand the difficulties and frustrations that she encountered as she tried to tell her story publicly. The reactions of both pro-conspiracy and anti-conspiracy JFK assassination groups on the internet was appalling. From either perspective, her story threatened their basic paradigms. They responded with insults, mockery and nit-picking. I begged her to stay off of the internet and to concentrate on writing a book that the public could read for themselves.

In 2003, I was encouraged when the History Channel aired “The Love Affair” as part of their popular series: The Men Who Killed Kennedy. This episode exposed for the first time that Judyth and Lee had been part of an effort to use cancer-causing viruses as a biological weapon. But it was withdrawn from circulation one week later, along with two other controversial episodes, for unexplained reasons.

In 2006, a long-awaited book was released, albeit in a print-on-demand format by a small publisher. It was withdrawn after only 85 copies had been printed. Its self-evident title was: Lee Harvey Oswald: The True Story of the Accused Assassin of President John F. Kennedy by his Lover. Fortunately, Judyth sent me one of the rare copies of that 700-page tome which, frankly, I struggled to read. But once I did, I found the basic evidence it contained so compelling, that I summarized the main points in two chapters of my 2007 book Dr. Mary’s Monkey. Not only did the paper-trail support both her claims of knowing Lee Harvey Oswald and of being trained to handle cancer-causing viruses, but her narrative of the people and events in New Orleans in the summer of 1963 helped explain the maze of connections between the Mafia, the CIA, business leaders, politicians, and the medical community. It was a confederation of corruption which Jim Garrison’s famous investigation had revealed.

The pursuit of power is a blood-thirsty game that knows few rules. It kills to silence. It punishes those who get in the way. It threatens those who might speak up. Lee was a casualty of this ugly game. His death preserved their secrets. He could not divulge his personal knowledge of the people and events leading up to Kennedy’s assassination, and he could not disclose the details of the biological weapon intended to kill Fidel Castro. He could not say who he really worked for. Those who run this game deemed his death necessary for “the good of our country.” Not only would it guarantee his silence, it would satisfy the public’s lynch-mob anger over the death of their President. Such was their plan. And it worked. But they overlooked something: The girl in Gainesville.

This book is thick with political intrigue, but it is also a story about something else: something softer, but stronger. It is about that invisible force commonly called “love.” A stubborn and enduring love, spiced with anger, frustration and yes, revenge. This is the story of the 20 year-old girl who screamed as she watched the man she loved murdered on national television, who saw him summarily convicted of the very crime that she knew he gave his life trying to stop. Judyth hid in silence for decades, afraid that she too would be murdered. But love eventually overcame fear. And love is ultimately the reason this woman decided to risk her life to tell the iconoclastic tale you are about to read.

You can listen to Madame Butterfly, or read Romeo And Juliet, but you are not likely to find a story about undying love in which a woman has “stood by her man” with more resolve. Despite their separation by death, the horrible accusations made against him, or the crude insults she has endured publicly for pleading his case, the bottom line remains that Judyth Vary Baker loves Lee Harvey Oswald. And she wants you to know the man that she knew: the man who ultimately died because of his efforts to save John F. Kennedy. Here is her story at last.

Edward T. Haslam

November 2009