A Military Occupation of a Different Kind

At 9:40 p.m. on February 15, 1898, a fiery explosion filled the darkened sky in Havana Harbor. The USS Maine, a 6,682-ton, second-class battleship filled with more than five tons of gunpowder, blew sky-high. Through roiling clouds of flames and black smoke fell debris of metal, burning wood and bloody body parts of more than 260 men whose torn remains sank into watery graves. After a short and less than thorough investigation, the explosion of the ship was blamed on Spanish terrorists who had been sent to Cuba to quell an insurrection. Stories of Spain’s torture and oppression of Cuban citizens had decent Americans screaming for justice. While the American government was hesitant to get involved in an international dispute, the USS Maine had been sent to warn the Spanish government that American citizens living in Cuba had better be left alone. Cuba was struggling for independence from Spain, and the seditious details reported by the media set the stage for the events to come.

Although several plausible explanations for the explosion were suggested, American outrage began to snowball, growing faster and larger as it rolled into the nation’s capital. Was it sabotage? Was it an explosive mine? It didn’t seem to matter, the result was the same. The one thing eyewitnesses agreed on was that there were two distinct explosions, seconds apart. “Remember the Maine— to hell with Spain!” became a rallying cry. And so, on April 25, two months after the explosion, the United States declared war on Spain.

Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt worried that there would be few men to volunteer to fight, but he was wrong. The War Department was inundated with volunteers, and Roosevelt resigned from his position to serve as second in command under his friend Leonard Wood, of the famed cavalry unit that would become known as the Rough Riders.

Military leaders used some practical insight to determine battle strategy. Knowing that the tropical climate of Cuba would be a detriment to U.S. soldiers, much recruiting was done in the southwestern states where residents were more accustomed to higher temperatures. As a result, the Rough Riders were a curious mixture of ranch hands, gold prospectors, lawmen, Indians, bandits, former Civil War soldiers and even some Ivy League college boys from the East who were right at home on polo ponies. The challenge, so it seemed, was to get the diverse soldiers to bond. By the end of May, hastily trained recruits made their way to Tampa, Florida, where they would board ships and head to Cuba.

The sentiments across the United States had certainly changed from a few decades earlier. As the men traveled from their homes to Florida, preparing to set sail for the conflict ahead of them, many noticed that old wounds inflicted some thirty-five years earlier in the War Between the States were beginning to heal. City boys from Boston rode alongside country boys from Tennessee, wearing the same uniform and cheered on by the same people, who waved the same flag. Confederate veterans, stooped over with age and infirmity, smiled wistfully at these young men as they passed by and shouted words of encouragement. There was, for the first time in decades, a sense of unity. And with that unity came a renewed sense of American pride.

But although more than three decades had passed, the fears of the mothers and wives were the same. Their expressions were identical in every war, every conflict. They could not hide the worry in their eyes, the sadness and dread that came with knowing that wars were not fought without great sacrifice of human life. The blood of their loved ones would soak the soil of a strange land, and God forbid, perhaps their bones would lie in unmarked graves forevermore. It was all too much.

Alabama was represented well by a Georgia transplant by the name of Joe Wheeler. Even though he was sixty-two years old, and despite the fact that, as a former Confederate general, he (officially) once bore arms against the U.S. government, he was determined to participate. Wheeler had been a Rebel to the bone and had even been imprisoned after the Civil War. He earned the nickname “Fightin’ Joe” while stationed in the New Mexico Territory before the Civil War. While he was escorting a caravan of civilians along the Santa Fe Trail, Indians attacked the covered wagons. Joe fought with all his might, firing his Colt pistols until the Indians abandoned their plans.

After the Civil War years, Wheeler settled down to married life at his Pond Springs, Alabama home and entered politics. He could have spent his golden years retelling war stories and planning his next political campaign, but the call of battle appealed to his deep sense of service. Washington politicians relented, and General Joe Wheeler took command once again.

General Joseph Wheeler as a young man. Photo courtesy Huntsville–Madison County Public Library.

THE BUFFALO SOLDIERS

When the War Between the States broke out, approximately 180,000 slaves enlisted to fight for the Union army. There are estimates that about 33,000 of the total 620,000 men who died in the war had been slaves.

In 1866, Congress passed a law to form two all-black cavalry and four all-black infantry regiments. Many of the all-black regiments, nicknamed the Buffalo Soldiers, were stationed in the Midwest and Southwest, where they came into contact with Indians, and it was the Cheyennes and Comanches who gave them the name. It was, on one hand, a sign of respect because the Indians admired the wooly buffalo that roamed the open country; on the other hand, the Indians thought the black soldiers’ hair resembled the coat of the shaggy beast. Some say they were given the name because they wore buffalo hides to keep warm during the bitter winter months. A large number of the Buffalo Soldiers had been slaves on Texas cattle ranches before the Civil War, and many others had either been born into slavery or were sons of former slaves.

While stationed in the Southwest, the Buffalo Soldiers worked to map the dust-blown Great Plains with their fields of lava rock and petrified sharks’ teeth from prehistoric times. The Buffalo Soldiers also put up telegraph wires, helped build frontier outposts and protected the railroad men from hostile Indians led by the likes of Geronimo, Sitting Bull, Chief Victorio and Lone Wolf. The men who laid the tracks for the iron horse to chug out west also had to contend with thieves and outlaws.

In Lincoln County, New Mexico, trouble was brewing. Two factions formed in support of the two merchants in the tiny town of Lincoln. There were ranchers and their hired hands on one side against ranchers and their hired hands on the other side. In the fall of 1877, Englishman John Tunstall was murdered. Over the next few months, there were retaliatory murders, and in the summer of 1888, a full-blown range war erupted with the infamous Billy the Kid in the middle of the fray.

The Buffalo soldiers, who were stationed at Fort Stanton, were sent to Lincoln with howitzers and Gatling guns, but as the battle raged, they were ordered to wait. The conflict ended very shortly after they got there when the second of the two leaders was shot to death. Billy the Kid escaped and became one of the most famous fugitive outlaws of all time.

Later, there was another history-making event. The Battle of Wounded Knee was fought to stop the escaped Indian chief Big Foot. It was a terrible battle, and many innocent Indians were killed. The Buffalo Soldiers got there almost too late but in just enough time to save the white soldiers from getting killed themselves.

Still later, members of the Buffalo Soldiers’ scouting party were surrounded by about fifty Apaches in the mountains near Deming, New Mexico, when Corporal Clifton Greaves used his gun as a club to free his men. Two years later, Apache chief Victorio ambushed them. Several Buffalo Soldiers won the Congressional Medal of Honor for bravery during these skirmishes.

But in the spring of 1898, the Buffalo Soldiers were preparing to fight a new enemy. Of the men who made their way to Cuba, the Buffalo Soldiers were the most highly trained, the most seasoned and the most experienced. And it would soon show.

THE TRIP TO CUBA

Even before the fighting began, there were disasters aplenty. The June heat in Tampa was steamy, suffocating and oppressive. The American soldiers, wearing prickly wool uniforms, were crowded onto the ships. The cavalry units, trained to fight on horseback, were forced to leave their horses behind due to lack of room on the ships. In fact, many men were left behind for the same reason. By the time they arrived in Cuba, many of the soldiers were wretchedly sick. Malaria and yellow fever thinned the ranks even further, and General Wheeler himself was sickened. He led a charge, however, and his men did double takes when, in his weakened state, he yelled, “Come on boys! We’ve got those Yankees on the run!”

Captain John “Black Jack” Pershing, commander of the Ninth and Tenth Cavalries known as the Buffalo Soldiers, was standing waist-high in a creek when he saw General Wheeler nearby on horseback. Pershing saluted his division commander just as an enemy shell landed between them. As the drenching water from the explosion subsided, Wheeler returned his salute. With that, both men turned back to the battle.

As shells exploded all around, some men ran in panic through the dense jungle. The Spaniards used smokeless powder so that it was impossible to determine where they fired from, while the Americans’ guns churned up thick black smoke, giving their positions away. Time and time again, Captain Pershing personally went back into the jungle to find lost troops, guiding and encouraging them back into battle. An officer who watched him described Pershing as “cool as a bowl of cracked ice.”

Confusion was everywhere as the men waited for orders, wasting valuable time. Lieutenant Jules Ord of the Seventy-first New York yelled to his men to follow him. The Rough Riders and the Tenth Cavalry joined the Seventy-first as they slowly made their way through the enemy lines. The casualties were horrific, but the Americans pressed onward. The men of the Tenth were divided in the confusion, and some followed Ord’s charge up San Juan Hill while others joined Roosevelt’s Rough Riders and John Pershing up Kettle Hill.

Lieutenant Ord was the first American to reach the top of San Juan Hill, with the help of the Tenth Cavalry. The brave young man was felled by an enemy bullet, becoming the first American to die on top of San Juan Hill. General Wheeler later remarked that it was the worst fire he had ever seen. The battle claimed half of the officers of the Tenth Cavalry, as well as one out of every five men in the unit. Pershing watched one of his Buffalo Soldiers hold up a wounded Spaniard’s head and give him the water out of his own canteen. A wounded officer asked Pershing how badly he was hurt. Pershing told him that he couldn’t tell; he then said, “But we whipped them, didn’t we?”

The Spaniards lost the battle, and although the war was not yet won, this was a turning point. The Americans, suffering in the intense heat, now had to cope with the onslaught of the rainy season. Malaria and yellow fever were rampant. Pershing and Wheeler were sick. On July 10, American forces began an intense assault on Santiago. The Spaniards finally surrendered on July 17, 1898.

Meanwhile, one month earlier, the town of Huntsville, Alabama, had extended an invitation to the heroes of the Spanish-American War. The “Splendid Little War,” as it was called, had ended in mere weeks, but many of the soldiers were still suffering from the effects of malaria and yellow fever. The president of the Huntsville Chamber of Commerce wrote to the secretary of war extolling the virtues of Huntsville’s immunity from disease, healthy air and available space. Apparently, the authorities were convinced enough to send Lieutenant Colonel J.A. Cleary in July to see for himself. By August, word had leaked out that regiments from Florida, Georgia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Indiana, Ohio, New York and Michigan would be sent to Huntsville to recover. It was predicted that Huntsville would have the largest military camp in the entire southeastern United States.

The military encampment was named Camp Wheeler to honor former Confederate general and now U.S. general Joseph Wheeler, but the number of soldiers would far outnumber the number of residents. Within weeks, thousands of soldiers began to arrive. They were weary, war torn, heartsick and homesick. The people of Huntsville welcomed them with open arms. Among them were the men of the Ninth and Tenth Cavalries, the Buffalo Soldiers, who arrived in October.

Though much advancement had been made in the lives of former slaves since the end of the War Between the States, some things had not changed. It was still the segregated South, and so the black and white soldiers were not stationed together in Huntsville. On October 18, 1898, the day of their arrival in Huntsville, members of the Sixteenth Infantry got into a skirmish with members of the Tenth Cavalry. Two Buffalo Soldiers were killed, one provost guardsman was killed and several others were seriously wounded. All had been shot.

Another guest of Huntsville, a member of Troop G, Second Cavalry, served as General John Joseph Coppinger’s bodyguard. But this wasn’t the first visit by Robert James. He had visited several years before, as a young lad, when his father, famous bank robber Frank James, was tried for robbing the federal payroll near Muscle Shoals.

There were those who were old enough to remember a time when the soldiers in blue were in Huntsville. During the Civil War, the Union army had occupied the town, and bitter feelings of that time still lingered. But this time was different. This time, General Joseph Wheeler himself wore a blue uniform.

Veterans of the Spanish-American War relax in Huntsville. Photo courtesy Huntsville–Madison County Public Library.

Members of the Tenth Cavalry pose for a picture in Huntsville. Photo courtesy Huntsville–Madison County Public Library.

Tents of the Spanish-American War veterans encamped in and around Huntsville. Photo courtesy Huntsville–Madison County Public Library.

General Joe Wheeler was a short, slim man with the demeanor and manners of the stately southern gentleman that he was. His men loved him, and he took care of them. The citizens of Huntsville, ten thousand strong, gathered on December 1 to cheer as he was presented with a fine horse. He changed the name of Camp Wheeler to Camp Albert G. Forse in memory of a man who died during the daring charge up San Juan Hill.

For his role in the Cuban campaign, John Pershing received special recognition from Teddy Roosevelt. He had also come to Huntsville with his men, the members of the Ninth and Tenth Cavalries. Five members of the Tenth Cavalry were awarded the Medal of Honor: Sergeant Major Edward L. Baker Jr., Private Dennis Bell, Private Fitz Lee, Private William H. Thompkins and Private George H. Wanton. In addition, another African American sailor was awarded the Medal of Honor: Private First Class Robert Penn, U.S. Navy.

The people of Huntsville entertained the troops with cotillions and dinners during their stay. Within weeks after Christmas, the veterans of the Spanish-American War began to leave town. In late January 1899, the Tenth Cavalry Band played a song dedicated to their comrades: “The San Juan Trooper’s Schottische.” On January 28, the Sixty-ninth New York Volunteers returned to their homes, and the Twentieth Cavalry left for Fort Clark, Texas. Huntsville, Alabama, returned to business as usual.

EPILOGUE

John Pershing, who once remarked that he would not make a career of the army because “there won’t be a gun fired in the world in a hundred years,” was a military genius who trailed Pancho Villa after the Cuban War, before his appointment as leader of the American Expeditionary Force. In 1917, he was sent to England, on a secret journey, to meet with King George at Buckingham Palace. The task before him was enormous, and at times the enemy seemed to be the Allied commanders he was there to help. Allied commanders had insisted that the American troops be incorporated into theirs, while Pershing insisted that they retain autonomy as American troops under American commanders. Soon after, the Germans overpowered the British Fifth Army in a move that threatened to defeat the Allied army. Pershing sent a letter of support to Marshal Foch, which served to revive the morale of the British and French armies. In part, his message read, “I have come especially to tell you that the American people will be proud to take part in the greatest battle of history.”

Pershing commanded over one million American and French soldiers during the attack on the German lines near Verdun in the Meuse-Argonne campaign. The forty-seven-day battle began in late September 1918 and took the Allied army deep into the Argonne Forest. The twisted and mangled limbs of the once-lush forest were left as evidence, along with the thousands of dead soldiers, of the terrible battle. General Pershing was given the title general of the armies of the United States. Although he had received numerous medals, when he walked solemnly behind the caisson that carried the body of the Unknown Soldier to his grave at Arlington, General John “Black Jack” Pershing wore only the Victory Medal, which had been given to every man who served in World War I.

General Joseph Wheeler returned to Alabama and was elected to Congress. At the age of seventy, while visiting his sister in New York, he died of pneumonia. General Wheeler was buried at Arlington National Cemetery, one of the small number of former Confederate veterans interred there.

Theodore Roosevelt was propelled into the White House, largely because of the reputation he earned in the Cuban War.

On November 11, 2009, an impressive statue of a Buffalo Soldier was finally erected in front of the Academy of Arts and Academics in Huntsville, Alabama. It took thirteen years to raise the money for the monument and pedestal and finally get it out for all to see. The school—and now the monument— is located on a small hill in northwest Huntsville. Long before the school was there, the small hill was known locally as Cavalry Hill. Although the street that passes in front of the hill is also known as Cavalry Hill, it will now be apparent why, 111 years after the last Buffalo Soldier left town.

General Joseph Wheeler on a horse presented to him by the people of Huntsville. Photo courtesy Huntsville–Madison County Public Library.

General Joseph Wheeler surrounded by appreciative Huntsville residents. Photo courtesy Huntsville–Madison County Public Library.

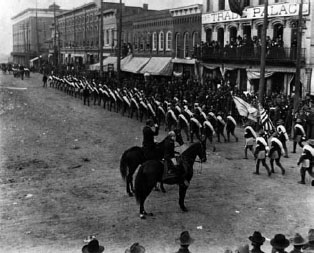

General Joseph Wheeler observing his men marching in formation around the courthouse square. Photo courtesy Huntsville–Madison County Public Library.

The cause of the explosion of the USS Maine has always been in question. Recent theorists have studied the facts and have come up with a sound explanation. It is now assumed that the ship was destroyed because of a boiler explosion. Who knows how the course of history would have changed if this had been discovered in time to avoid the Splendid Little War.