The Ghosts of the Forks of Cypress

June 6, 1966, started as an unusually hot and muggy day. By late afternoon, dark clouds had gathered in the sky and rain began to fall. An ominous stillness in the air alerted animals, and they began to grow restless. By nightfall, the angry roiling clouds opened, and sheets of rain pummeled the earth. White-hot bolts of lightning slashed through the dark sky. Across the Midwest and South, tornadoes touched down, leaving a wide swath of death and destruction. In Lauderdale County, Alabama, lightning struck the earth with ever-increasing frequency; each flash eerily illuminated a dark and empty mansion standing on a hill overlooking what was once an enormous plantation. It seemed as if Mother Nature was on a mission. Another flash of lightning streaked across the sky toward the earth, ending with an explosion of sparks. Within minutes, fire raged through the beautiful mansion. Flames licked the enormous columns, burning far more than wood, glass and plaster. The Forks of Cypress and over 140 years of history were gone—and, perhaps, the restless ghosts.

In the days before and after June 6, 1966, fifty-nine tornadoes touched down, leaving eighteen dead in the devastation. About four miles outside of Florence, Alabama, wisps of smoke rose from the smoldering ashes of an antebellum mansion. Twenty-three columns, two stories high, were all that remained, scorched but standing like silent, ever-vigilant sentries.

The man who built the mansion more than a century before, James Jackson, was born on October 25, 1782, in Creeve, County Monaghan, Ireland. James’s mother died when he was only two years old, leaving eight young children, all under the age of thirteen, without a mother’s love and gentle guiding hand. Jackson’s widowed grandmother stepped in to help her son raise the young children. She lived an additional nine years, and shortly after her death, James left the stone two-story, ivy-covered house to live with his uncle in Dublin. He studied civil engineering, but his education ended abruptly with the Rebellion of 1799. Seventeen-year-old James escaped Ireland, along with his uncles Henry and John, to seek refuge first in Germany and then in the United States. After some time in Baltimore, James Jackson moved again. Records indicate that he was living in Nashville by 1804.

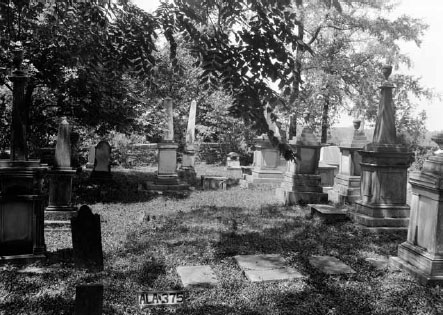

Forks of Cypress.

The Jackson family cemetery at the Forks of Cypress. HABS-HAER photograph.

To say that James Jackson was ambitious and hardworking is an understatement. He had a mercantile business in Nashville and spent much time with another ambitious fellow with the same last name—Andrew Jackson. In 1810, James married a twenty-year-old widow with a young daughter. His attention soon turned to the fertile land in the Alabama Territory now opened up for sale. In 1817, General John Coffee, Supreme Justice John McKinley and James Jackson organized the Cypress Land Company and began a collaboration to lay out the town of Florence, Alabama. No doubt, his background in civil engineering served him well.

Jackson’s own home was a masterpiece. While living temporarily in a log house, Jackson started his home in 1819 on a hill where, according to legend, a wigwam had once stood. The man who had lived in it was the Cherokee chief Doublehead.

The mansion, named the Forks of Cypress for the nearby Big and Little Cypress Creeks, took three years to complete. Twenty-four massive columns surrounded the home. They were constructed of pie-shaped bricks and mortared with a concoction of sand, molasses, charcoal and horsehair. The columns, wider at the bottom than at the top to give the optical illusion that they were much taller, were then covered with plaster. The finished home was stunning.

James Jackson had come a long way from his humble beginnings in Ireland. By the time Alabama was admitted into the Union as the twenty-second state, he was a wealthy man. James turned his attention to politics and a wealthy man’s indulgence: horse racing. No doubt his interest in horses was influenced during his youth in Ireland. His uncle Hugh Jackson owned an award-winning mare named Jane, and family lore claims that upon the mare’s death, she was buried just outside Hugh Jackson’s door.

James Jackson was serious about his horses and the sport of racing. He had a racetrack built on his three-thousand-acre cotton plantation. Three horses were imported from England: Glencoe (once owned by King George IV), Leviathan and Pocahontas. Some of the finest racehorses were bred from them, and an amazing fourteen descendants of Glencoe went on to win the Kentucky Derby. Peytona, sired by Glencoe, had a stride of twenty-seven feet, and she remained undefeated for some time. In a wager to settle which region of the country raised superior racehorses, Peytona was chosen to race against her northern equivalent, a mare named Fashion. Peytona was led by a stableboy to Long Island, New York, from Florence to represent the South. This famous race, which occurred on May 15, 1845, was so important that the artists Nathaniel Currier and James Merritt Ives were present to record the event in color. Carrier pigeons waited to carry the results to New York newspapers. It was estimated that a crowd of 100,000 people would come to see the historic race. Peytona did not disappoint the people of the South. She won the race, and the newspapers had the results within nine minutes of the finish.

Peytona’s win did not come without sacrifice. Immediately after the race, her front legs were declared to be feverish, and she did not compete in the Jockey Club Purse days later. When she next competed against Fashion, she was defeated, and soon it became clear that Peytona’s racing days were behind her.

Although James Jackson watched the early progress of Peytona after her birth, he did not live long enough to appreciate Peytona’s famous victory. He died in August 1840 at the age of fifty-eight. His newspaper obituary gave a detailed account of Jackson’s unexpected death:

He departed this life suddenly on Monday last, between the hours of twelve and one o’clock in the 58th year of his age. Mr. J. had experienced, a week or two before his death, a violent and dangerous attack of fever, but had recovered from it sufficiently to take moderate exercise, and on that fatal morning rode out upon his plantation as was his custom when in health. It is probably however, that in this occasion he presumed too far upon his restoration and his naturally robust and stirring habits—he returned to the house with a chilly, full sensation, and before one o’clock was a corpse.

Over two decades later, much of North Alabama was occupied by Federal forces in the Civil War. Colonel James Jackson Jr., who was forty at the beginning of the war, had inherited his father’s fearlessness and love of beauty. Although he was educated at Princeton and a member of a prominent family, he enlisted in the Confederate army as a private in the Fourth Alabama Infantry. Jackson was shot in the chest in the first Battle of Manassas and sent home. After his recovery, he organized the Twenty-seventh Alabama Infantry and was commissioned a lieutenant colonel. He, along with most of his company, was captured at Fort Donelson in February 1862. After seven months in the Johnson’s Island prison camp, he was exchanged. Jackson took over as colonel of his regiment upon the death of Colonel A.A. Hughes and went on to Vicksburg, where he and his men remained until July 1863. Interestingly, while in Vicksburg, he ordered his men to fix their bayonets and charge a Georgia regiment as it needlessly trampled the flowers of a private home. The Georgians backed off immediately and were no doubt surprised at Jackson’s need to preserve a little beauty in the midst of chaos.

By 1864, about 150 members of the Ninth Ohio, riding white horses, occupied part of Lauderdale County, harassing and living off the civilians. Colonel Jackson had been informed that they were living in and around the Forks of Cypress, where his widowed mother also lived. Jackson quickly gathered together his most fearsome and trusted men to cross over enemy lines and run them out. On the night of April 11, he and his men ferried across Tuscumbia Landing on the Tennessee River and took a slave guide, who informed them that it was actually the home of Jack Peters that was occupied. They crept quietly on, avoiding the roads, until they were within 150 yards of the campfires of members of the White Horse Company. At the signal, they charged, firing their weapons and yelling the name of the dreaded Nathan Bedford Forrest, sure to strike fear into the hearts and minds of the enemy. Forty-two prisoners were taken along with forty-four white horses. Jackson ordered that the mules and cattle taken from local civilians be turned loose in the fields in the hope that they would return to their owners. James Jackson Jr. survived the war and died in 1879 at age fifty-seven.

The mansion survived the Civil War as well and continued on as one of the showpieces of architecture in Lauderdale County. Along with the survival of the mansion came an increasing number of stories of ghosts haunting the estate. In the early 1960s, the late Faye Axford, a well-known writer and historian from nearby Athens, visited the mansion on several occasions. Each time, there were unexplained occurrences.

During her first visit, Faye settled in for the night in one of the guest bedrooms. Sometime shortly after she drifted off to sleep, the door to her bedroom slammed shut. She quickly opened her eyes and cautiously looked about the darkened room. After a few minutes, assured that she was indeed alone, she was overtaken by sleep once again. A woman’s scream startled her into consciousness, and this time, her nerves were rattled. Within a short time, she was once again shaken by the loud blast of a gunshot in the darkness. She did not sleep for the rest of the night.

The next morning, Faye wandered downstairs, bleary-eyed and exhausted. Her host was surprised when she told him of her sleepless night, but when she told him what had happened, he had an explanation. The slamming of the door was caused when the air conditioner came on. The woman’s scream was not a woman at all but a neighbor’s peacock wandering past the home, making much the same sound as a woman. The gunshot was explained with an apology. The host had fired his gun in order to scare off local students of Florence State who frequently drove out for late-night beer sessions.

While the events of her first night were easily explained away, none of Faye’s other experiences could be dismissed in the same manner. On another visit, Faye had settled in to her guest room, and while rummaging through her purse, she accidentally dropped her wallet behind the dresser, where it slipped down to the floor. She started to retrieve it but was called down to supper with the others guests. She made a mental note to remember to find it when she returned. But after a pleasant meal, she returned to her room only to discover the wallet lying on top of the dresser. Faye asked her host who had gone to the trouble to get it for her so she could properly thank him. Her host had no idea what she was talking about, and the subject had not been discussed at supper that night. Perhaps it was the ghost of a tall stately woman that was known to walk the halls and grounds near the home. The ghost was said to wear old-fashioned clothing and seemed to be in search of something—or someone.

It could have been the ghost of Parson Dick, the slave who served as the butler inside the mansion. He was married, but his wife lived on a nearby plantation, which he frequently visited. During the Union occupation, Parson Dick rode a horse one day to pay a visit to his wife. He never arrived at his destination and was never seen or heard from again. Is he lost, looking for his way, or is he trying to communicate the mystery of his fate? Or could the ghost be that of a mulatto slave named Queen, thought to be the daughter of James Jackson Jr., who left the Forks of Cypress at the end of the Civil War, traveled to Decatur and went to Tennessee? Although Queen was treated differently—perhaps a little better than most of the Jackson family slaves—her father did not acknowledge her as his daughter. The beautiful former slave was the grandmother of writer Alex Haley, whose family stories were incorporated into his novels. It would make sense that, given the history of the home and the number of people who once lived there, more than a few ghosts remained.

Columns are all that remain of the Forks of Cypress. Photo courtesy Patrick Hood of Patrick Hood Photography.

On the occasion of Faye’s next visit, she was shown to a different guest room. She put down her suitcase and laughingly made a comment out loud, something to the effect of, “I suppose I will not be staying with the ghost in the other room tonight.” No sooner had the words come out of her mouth than a cut-glass candy dish flew across a table and clattered loudly onto the floor. She was shaken by the response of whatever, or whomever, she had encountered—but not enough to stay away. She was invited again to visit the Forks of Cypress and gladly accepted. She did not make that trip, however, because she planned to arrive on June 7, 1966—the day after the home burned to the ground.