ROCKET MAN

Flying an airplane in World War I was extremely dangerous. The newly invented planes were made of flimsy wood, cloth, and wires. They could be shot down by machine guns or crash in a ball of fire. Then something strange began happening to the pilots. As they flew higher and dove faster during combat fights, the pilots began passing out—while they were flying the planes.

Doctors were baffled and began calling the strange phenomenon “fainting in the air.” In reality, the pilots were passing out because of the effects of gravity forces on the body.

Gravity forces, or G’s, are the amount of pull on the body. One G is equal to what a person feels when he or she is sitting in a chair on Earth. When speeding up or slowing down very quickly, we feel more G’s, like on a roller coaster. At the bottom of a hill on a roller coaster, you feel more G’s and at the top of the hill the body feels less G’s. Airplanes experience increased G’s as they are moving fast and as they are turned to the left, right, or sent upward.

G forces also came into play when an airplane crashed. At the beginning of World War II, scientists believed that the human body could only survive 18 G’s, or 18 times the force of gravity, in a crash landing. Because of this, cockpits were only designed to withstand 18 G’s, but as the war went on, many pilots walked away from crashes that had much higher G forces. Doctors and scientists were amazed.

Dr. John Stapp was a physician in the Air Force, and he believed that what killed most pilots was not the G forces but the metal of the plane mangling the pilot’s body. He decided to begin testing to see how much the human body could withstand. Could a pilot be saved if he ejected out of the plane instead of going down with it? What kind of parachute or protection could save the pilot?

As they flew higher and dove faster during combat fights, the pilots began passing out— while they were Jlying the planes.

No human had ever tested what gravity forces the body could survive. There was no data to help engineers build safer cockpits or design better parachute harnesses. Stapp decided that he would investigate the effect of G forces on the human body, and he would volunteer his own body as a test subject.

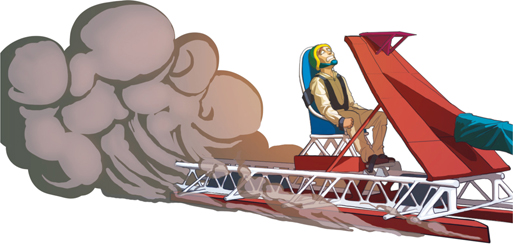

Stapp and his research team built a rocket sled in the American Southwest desert. The sled ran on rails and had an actual pilots seat for the rider. A rocket was attached to the sled to push the seat forward as fast as possible. Then brakes, and later water, were used to stop the sled as quickly as possible. The fast acceleration and immediate deceleration created gravity forces on the human body.

The team spent a year testing and preparing the run before they launched a human. In 1948, they began testing the sled with human subjects. Stapp was the first and most frequent volunteer. He didn’t like to allow any other volunteers to ride the rocket sled for two reasons: (1) because he feared for their safety, and (2) because he liked to know the test results personally. He felt he could make adjustments better if he had firsthand knowledge.

Stapp spent 5 years experimenting with the rocket sled. He strapped on more powerful rockets. He went from two rockets up to nine. His rocket sled could produce 50,000 pounds of thrust. And Stapp learned what the human body could endure.

When his body was hit with 18 G’s, he experienced concussions, lost the fillings out of his teeth, and twice broke his wrist. But the worst problem was with his eyes. The heavy forces caused the capillaries in his eyes to burst and gave him white-outs, where he had blurry vision and could not see. And this was when he was riding backward in the pilot seat. Facing forward, it was worse. Then, the blood was pushed up against his retinas and he experienced red-outs.

He strapped on more powerful rockets. He went from two rockets up to nine. His rocket sled could produce 50,000 pounds of thrust. And Stapp learned what the human body could endure.

Stapp proved that the eyes were the most vulnerable part of the body when facing high gravitational pull. Stapp also helped design better harnesses for parachutes and restraining straps for cockpits. He discovered that having pilots breathe pure oxygen for 30 minutes before flying would prevent the bends (getting sick from changes in altitude).

His final run was his fastest. In December of 1954, he launched with nine rockets for thrust and was clocked at 632 miles per hour. In 5 seconds, he slammed into two tons of wind pressure and then came to a stop. The gravitational forces made his 168-pound body act as if it weighed 7,700 pounds. He had survived more than 40 G’s of deceleration and had become the fastest man on Earth.

The heavy forces caused the capillaries in his eyes to burst and gave him white-outs, where he had blurry vision and could not see.

When his sled came to a stop, he had to be immediately rushed to the hospital. All of the blood vessels in his eyes had burst. He had cracked ribs, broken wrists, and difficulty breathing. But Stapp recovered and had no lasting damage.

His experiment proved that a pilot could survive ejecting from an aircraft traveling at 1,800 miles per hour at 35,000 feet. He also proved that with an adequate restraining system, a pilot could survive a crash of 45 G’s. Because of this, jet pilot seats were modified for stronger impacts.

Dr. John Paul Stapp continued working for better, safer airplanes and transportation for the rest of his career. He died in 1999 at the age of 89. When he died, he still held the record for the fastest human on Earth.