AFTER their marriage, early in 1865, John and Mary Costello prepared to set out again to the far north. They had taken up a block in the spring country between the Warrego and Paroo Rivers, just south of the Queensland border. The season was then said to have broken well in the north and they thought this would at least be a good place on which to start, though, later on, they thought they might expand into better country.

John’s mother had protested but she soon saw that her son was not to be put off. The thought, however, of the brave young couple going off alone into the wilderness had been more than either she or her husband could endure and they decided at the last to leave a manager in charge of their own property and accompany them.

Patsy would also have liked to join the party with his wife and baby daughter, but the child became ill, and he knew she could not have survived a journey to the lonely north. He waited, hoping that she would become stronger and in the meantime two sturdy sons, Michael and John, were born. Still the little girl did not improve and it was not until after her death, at three years old, that the family decided at last to join the Costellos at Waroo Springs.

They had heard from their Costello relatives that settling in had proved difficult. The seasons had not been very good and some of the springs they had thought permanent were drying up.

At first the natives had given no trouble, but later they had taken to chasing and spearing the stock and had killed one of their stockmen while he lay asleep in his swag. None the less a few natives had drifted in to the homestead and were making good stockmen. One in particular, whom they called Soldier, was an outstanding native, very tall and straight and a splendid rider. This boy had become devoted to the family and had told them that there was better country and some splendid, big rivers somewhere to the northwest. John Costello suggested that when Patsy and the rest of the family joined him they should abandon Waroo Springs and move on together in search of this promised land.

Soon the family in Goulburn was ready for the northward trek, with their two covered waggons with bunks inside that could be folded up when not in use, two drays full of equipment and stores for the journey. Everything they possessed was to go with them, including their furniture, their Irish linen and lace, their silver, china and glassware, for this time there was to be no turning back.

Patsy’s greatest sorrow was parting with his mother, who was forced to stay behind with her youngest, unmarried daughter and little son Jerry. It was arranged that she should divide her time between Darby Durack’s family and her married daughters until, when a permanent settlement had been made, they might all move north to be together.

It was in June 1867 that the family cavalcade moved out of Goulburn to catch up with the stock already started north along the Lachlan in charge of hired stockmen. Mrs Patsy, with the two-year-old Michael and the baby John, travelled in the buggy with her husband, while Stumpy Michael and another assistant brought on the heavier waggons. At night the entire party camped together, fires were lit, and billies, cooking pots and camp ovens in which bread had been rising on the way came rattling off the cook’s waggon. Every man took his turn at watching the cattle while the others gathered at the fire, and sometimes Patsy would liven the party up by playing his fiddle and by making up rhymes of his own to sing to well-known tunes. Soothed by the sound of music and voices the cattle would graze peacefully, some edging close to the camp and throwing themselves down within a few yards of the fire.

‘Merrily sings the drover

With his stock so fat and sleek,

Up to the border and over,

His fortune for to seek. . . .’

The first stages were fairly easy travelling, over wheel-made tracks and past farms and stations, and they would sometimes stay a day or two with hospitable bush people, who were touched to see the little family forging on into the never-never. They would stock up at bush towns, that grew sparser as they went along, until two hundred miles north of Goulburn all signs of settlement petered out and they followed a compass course through more or less trackless bush.

They reached Bourke after about three months on the track, and having stocked up with stores for the last time, moved north-west to the Costello station between the rivers. We can picture the joy of that reunion, all the questions and exchange of news. The young Costellos now had a two-year-old son to compare with Patsy’s eldest Michael. They were still full of hope and good cheer, but as little rain had fallen in those parts for a long time Costello was anxious to move on to a big permanent waterhole he had discovered on Mobel Creek, over the Queensland border.

‘We can make a depot there for a while,’ he said, ‘and after rain we can move out and find still better country further west.’

As there was no hope of selling out in such times it was simply a matter of packing up, mustering the stock and abandoning the little bush homestead to the wilderness.

The boy Soldier and a few of his relatives came along with the family when they set out at last into the trackless land. There was a little more feed and water than on their previous, ill-fated journey, but as they pushed north of the border they could see that the drought was closing in on them again. The heat was almost unendurable and before long most members of the party became sick through drinking stagnant water.

At this stage Patsy and John Costello may well have regretted bringing their women and children into this desolate place. They could expect no help from the outside world and knew they were completely at the mercy of the season and the unpredictable black tribespeople. In these times it is hard to believe that men took their families into this unknown land, and it is hard even to write that the Costellos’ little son actually died on this desolate journey and was buried in a lonely grave beside the track.

Still they struggled on and at last reached their temporary destination on Mobel Creek. The waterhole, between tattered paperbarks and coolabahs, was the colour of mud, but it was good water for a drought year and there was just enough grass about to keep the stock going for a little while. The men put up slab huts and a yard, watched their stock and soon got on good terms with the local blacks, who came shyly in to look at the strange newcomers and their children.

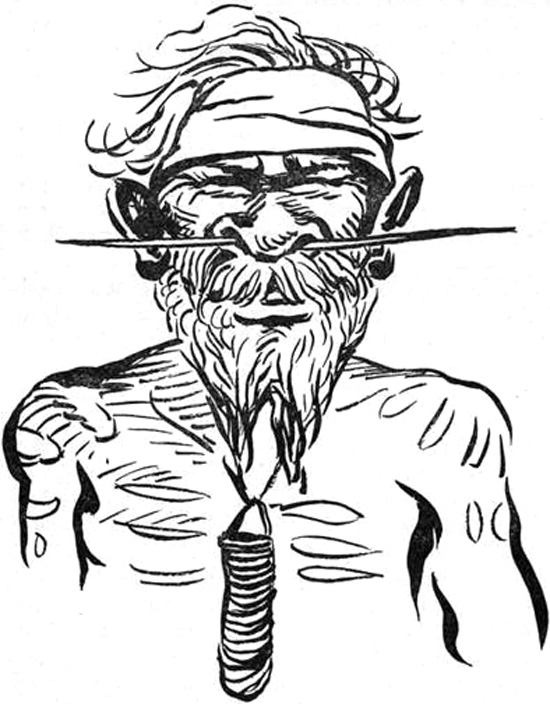

An old man with a long bone through his nose . . .

One fierce-looking old man with a long bone through his nose and many tribal scars on his body at once attached himself to Patsy, quickly picked up a little English and even learned to ride a horse and tail the cattle. Mrs Patsy was frightened of him at first, especially when she found him one day lifting the net and peering at her baby son. She was sure such a terrifying looking savage could be up to no good, but later on she realized that old Cobby, as they called him, had taken them to his kindly heart and would risk his life to protect them.

Not long after their arrival at Mobel Creek a baby girl was born to John and Mary Costello. Then, like a blessing from heaven, the rain came at last, filling the rivers and tributaries and bringing sweet, new grass to the bare plains. The stock fattened quickly on this good pasture and John Costello decided to drive a mob of two hundred horses to sell in South Australia. It was a journey that only the most skilled and confident bushmen could have undertaken, for most of the 800 mile journey was still unexplored and certainly no one had ever dreamed of taking stock that way before.

As helpers Costello took his wife’s brother, Jim Scanlan, and the two faithful Waroo Springs natives, Soldier and Scrammy Jimmy, and they proved an excellent team. Their route lay west to the Wilson River, south down the broken watercourse of the Strzelecki to Lake Blanche and Lake Frome and thence to the stock market at Kapunda, near Adelaide. They set out as though such journeys were very much a matter of course, but when they reached their destination without the loss of a single beast people could hardly credit they had come that hazardous distance from Queensland’s arid west. They were received like heroes and people for miles around turned up to the auction sale. Their horses brought £15 a head, which, multiplied by 200, was a small fortune in 1868. They were jubilant as they set off for their home in the wilderness, wondering whether, by now, Patsy and his brother had found the better country for which they had meantime gone in search.