DURING the long newsless months that followed Patsy tried to sink his anxiety in constant movement. He rode restlessly about the countryside, went several times to Brisbane to supervise the building of his new house, and twice to the New South Wales town of Molong to reassure his Uncle Darby’s widow about her brother Tom and her three big sons.

In March ’85 they received a wire to say that all was well and some weeks later a letter from Darwin with further brief details of the trip. The party was then camped on the Leichhardt River and had obtained provisions and despatched mail to Darwin from a depot that had been set up for droving parties near the mouth of the Roper River. They had lost nearly half the cattle, for numbers had perished in the Queensland drought and of pleuro before it was controlled, while further animals had been speared, chased off by blacks, or taken by crocodiles in the Gulf rivers. That was about all, they said, except for the fever, on which they wasted few words since everyone in the Australian bush had experienced fever of some kind. This form, they suspected, was malaria, carried by the teeming mosquitoes from one man to another, and, since none escaped it, hardly worth mentioning. None-the-less the almost invisible dagger of the little winged anopheles accounted for more lonely graves along the stock routes of the north than native spears or any other single cause. It is terrible to think of how men with aching heads and limbs and parched throats rode doggedly on beside the cattle, mile after mile through the hot and comfortless wilderness. To these hardy and dedicated drovers the fear of sickness and even death was far less than that of being a burden to their mates or in any way delaying the progress of the cattle to their promised land.

Later the family was to hear the stark details of a wet weather camp on the wild banks of the Roper. The drovers had managed to swim their cattle across the flooded stream but the waggons were trapped on the other side until the water level fell. By this time the natives had pillaged the supplies and further provisions had to be obtained from the depot. All this meant delay, and a rule of the road that no drink was to be brought into the stock camps somehow broke down. Traders who brought supplies by ship from Darwin began smuggling rum to some of the fever-stricken stockmen, who no doubt thought it might help to ease their sufferings and give them fresh heart for the journey. Of course it made matters worse and the leaders of the party, returning with the supply waggons, found some of their party too sick to move. John Urquart, the fine old bushman who had saved the day by inoculating the cattle on the Nicholson River, was by this time delirious and it was feared he might die if they could not get him on board a schooner to seek medical aid in Darwin. Before the boat arrived to take him away, however, Urquart, tortured by fever and depression, had ended his own life. He had been much loved and respected by his companions, one of whom, feeling, as the party was about to move on, that he too had reached the limit of his endurance, put an end to his misery in the same way.

With heavy hearts the party pushed on west through the steaming mire and rank green grass of the Territory wet season.

In May of the same year a more cheerful message by Overland Telegraph from Elsey Station told that the party was travelling well and hoped to reach the Ord within five months. The next news was from Black Pat to say he and Tom Hayes had left the drovers at the Victoria River and were chartering a schooner to take them with supplies from Darwin to Cambridge Gulf, where they would await the arrival of the party. This had been the original plan but after the loss of the two drovers on the Leichhardt it was feared no members of the party could be spared. By good luck they had met up with a drover and two natives who had been with Buchanan into Kimberley and who agreed to accompany the cattle on the last difficult lap. The natives proved to be none other than Pintpot and Pannikin, who had gone across Kimberley with Stumpy Michael’s party and were delighted to meet up again with their old friend Tom Kilfoyle.

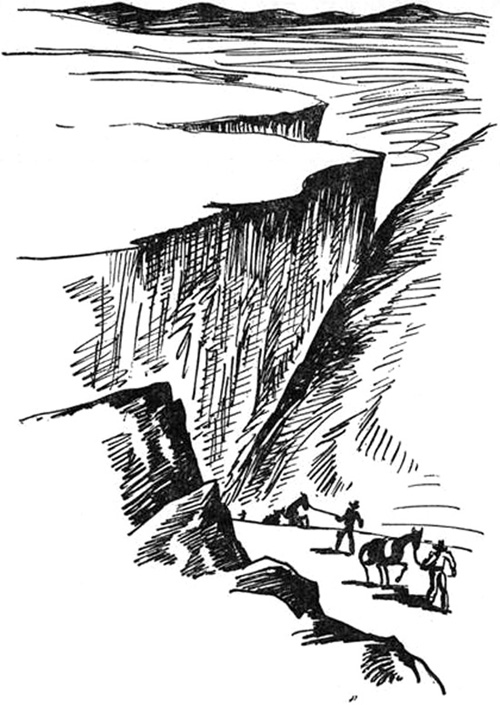

. . . the perilous canyon gorges . . .

It was many anxious weeks before Patsy and his family heard of the last, nightmare stages of that now famous trek. The drovers knew that of all the wild and dangerous places they had come through there had been no such fearful hazard as the Wickham Gorge, through which ran the only stock route to the west then known. This was a narrow pass between sheer canyon cliffs where the winding palm-fringed river had cut its way in ages past. So far only Buchanan’s party, about a year before, had attempted this perilous task and the three new hands, who had been with this expedition, told how even these experienced drovers had been unable to get through without some loss of stock. They warned that a good night’s rest and steady nerves were needed, for if the cattle were to panic in this pinch it could mean not only the complete destruction of the mob they had nursed along for over two years, but the loss of human lives as well. The natives were numerous and reportedly hostile in this region and if it occurred to them to launch an attack from the cliffs above everything could well be lost. It was decided to bring the cattle through in small lots, as slowly and quietly as possible, and to use every trick of the drover’s trade to avoid a fatal rush.

Although cattle that had survived so many miles of hard travelling and were so used to being handled stood a far better chance of getting through than a newly mustered mob, they soon became footsore and frightened as they slipped and stumbled over stones and other obstacles in the narrow pass. Even small numbers at a time made an almost deafening noise as the clatter of hard hoofs, and the rumble of nervous bellowing, mingled with the steadying voices and cracking stock whips of the drovers, was magnified many times by the echoing rock walls of the ravine. Several beasts, on the outer edge of the precipice, slipped and went hurtling to their death but the rest plunged on, urgently straining towards the far, sunlit opening of the gorge.

. . . through the perilous canyon cliffs . . .

And then, as if this were not enough suspense, the drovers’ apprehensive upward glances revealed that their progress was being observed by a large gathering of tribal warriors who stood, with their long-handled spears, outlined against the sky. For all their varied experience of Aborigines the white men could never predict how a strange tribe would behave and had no way of telling whether the excited gestures of the blacks should be taken as friendly curiosity or angry threats. They knew, however, that the fate of their long expedition now depended on the mood or whim of the wild people.

Perhaps it was the very drama and excitement of the scene that decided them after all to let the show go on. No spear was thrown and the dark figures following along the edge of the cliff disappeared as the drovers and their herd neared the end of the gorge.

Through the ravine at last, with fewer losses than they had believed possible, the men sighed with relief and their hearts rose as the cattle strung quietly on and over the border into the western colony. Shortage of food was now their main problem for the stores they had brought from the Roper River depot had almost gone.

Lack of important items of diet had caused sores to break out on their faces and limbs and every small scratch festered painfully. With the help of the two native boys they scrounged the bush for natural food—wild honey, yams and lily roots—and as they rode along their chewed, like the stock, at pigweed and other succulent plants. Fever, that had improved somewhat during the cooler months of the year, began to harass them again as the season progressed and, had they not known that the journey was almost to an end, some would not have had the heart or strength to continue.

Following the Negri River to its junction with a larger stream, they knew they had reached the Ord at last, and Tom Kilfoyle here pointed out the tree they had marked on finding this spot in September ’82. He recalled the relief and joy of this party and their resolve somehow to get stock across the continent to drink from the deep Kimberley streams and fatten on the richly pastured plains. Now, almost exactly three years later, after two years and nine months’ travelling and at a cost of something over £70,000 they had arrived—although with only about half the stock they had started with.

So much they had achieved, but the task of pioneering a vast area inhabited by native tribes still lay before them.

And this time, as they eased their cattle down the steep banks to drink from the great river the watchful natives, on the red cliffs above, did not stay their spears. Perhaps they sensed that these men and their mighty herd were not merely passing through their hunting grounds but had come intending to stay. A shower of long-handled, flint-topped spears came hurtling and whistling into the sprawling river bed. Pandemonium broke out as terrified beasts, some trailing spears from flanks and shoulders, floundered at the water’s edge, some plunging and milling in a maddened circle midstream. Some of the frightened horses swam the river and went galloping off on the other side. One of the men had his shoulder grazed by a glancing spear and others escaped by inches. All had agreed that to fire a shot must be a last resort and only in the extremity of life or death. This the drovers now knew to be their only chance. The leaders gave the signal. Revolvers were drawn and a sharp volley fired at the cliff top. With one last shout of rage and terror the natives dispersed and vanished from sight.

It was a bad beginning and the stockmen realized that there was to be no peaceful conquest of this wilderness, for the tribes had declared war. Day and night they must remain on their guard, wary of ambush by day and stealthy attack by night, resorting to the old trick of rigging a camp in one place and going off quietly to sleep elsewhere. Two mornings later Long Michael removed twenty spears from the dummy swag he had set up under his mosquito net!

To the newcomers it was not yet the home country of which the poet Jack Sorensen was to write in later years:

‘And sometimes on the winds that set the Leichhardt pines a-sway

I’d hear the cattle coming down the road from yesterday—

Coming home—the long trek over and a song would rise in me

Such as cheered the weary drovers striving West to Kimberley

Drought driven out of Queensland;

Flood driven out of Queensland;

To the dreamland, the stream land—

My grass gold Kimberley!’

Meanwhile Black Pat and Tom Hayes, anxiously waiting at the lonely Gulf, had run up a shack to house themselves and the precious stores. It was not long before three members of the party were on their way down the river to announce the arrival of the cattle and to return with much-needed stores and a pile of mail and newspapers. One letter had contained disturbing news of the widowed Mrs Durack who, sick with worry for her three sons and her brother, Tom Kilfoyle, had declared she would surely die if they did not soon return to prove themselves alive. They were a devoted family and it was at once decided that Kilfoyle, Long Michael and Big Johnnie should start back overland without delay. A three thousand mile journey, more or less, would be child’s play without the cattle, they said, and calculated on making it within about six weeks.

All this time Patsy had remained at Thylungra, unable to face the final break with the home he had built and loved, the country he had brought to life out of his dreams and the natives who had been his devoted helpers. At last, however, he could find no further excuse to remain and moved with his family to Brisbane and the now completed city home. ‘Maryview’, as he had named it, was the fine mansion he had always promised his family. From its wide balconies he could look down over a circular drive from the main gates, over stables, servants’ quarters and outhouses and across terraced lawns running almost to the river’s edge.

He at once organized a grand house-warming party that went on for several days and to which he invited friends and relatives from far and wide. Some prophesied that he would soon be off like John Costello in search of yet more new country, but Patsy declared he would henceforth conduct his affairs from his comfortable home. He had always been sociable and yearned to enjoy the things for which he had so little time in his busy life. His two brothers, Stumpy Michael and Galway Jerry, were of much the same mind and there seemed no reason why they should not enjoy the money they had made. In a very short time they and their families were at the centre of a social life of fashionable race meetings, theatres, garden parties and other entertainments.

Patsy’s elder sons, Michael and John, came back from college at the end of the year. They had gone to school much later than most boys but they proved good scholars and had matriculated with flying colours. Patsy, although tremendously proud of their success, was shocked to hear that they planned to return to the University and study for professions. It seemed to their pioneer father as though they were throwing away all he had worked and striven for. It had cost him dear to get cattle to ‘the land of neither drought nor flood’ for which he had been seeking all his life. The Ord River country was to have been his sons’ heritage and he was astonished to find they did not want it. However, he said they had their own lives to lead and he would not stand in their way.

And then, as so often in Patsy’s life to this time, fate stepped in on his side.