10 A CROWBAR OR A KEY

THE DROWNED GODS CAME for her as soon as she fell asleep.

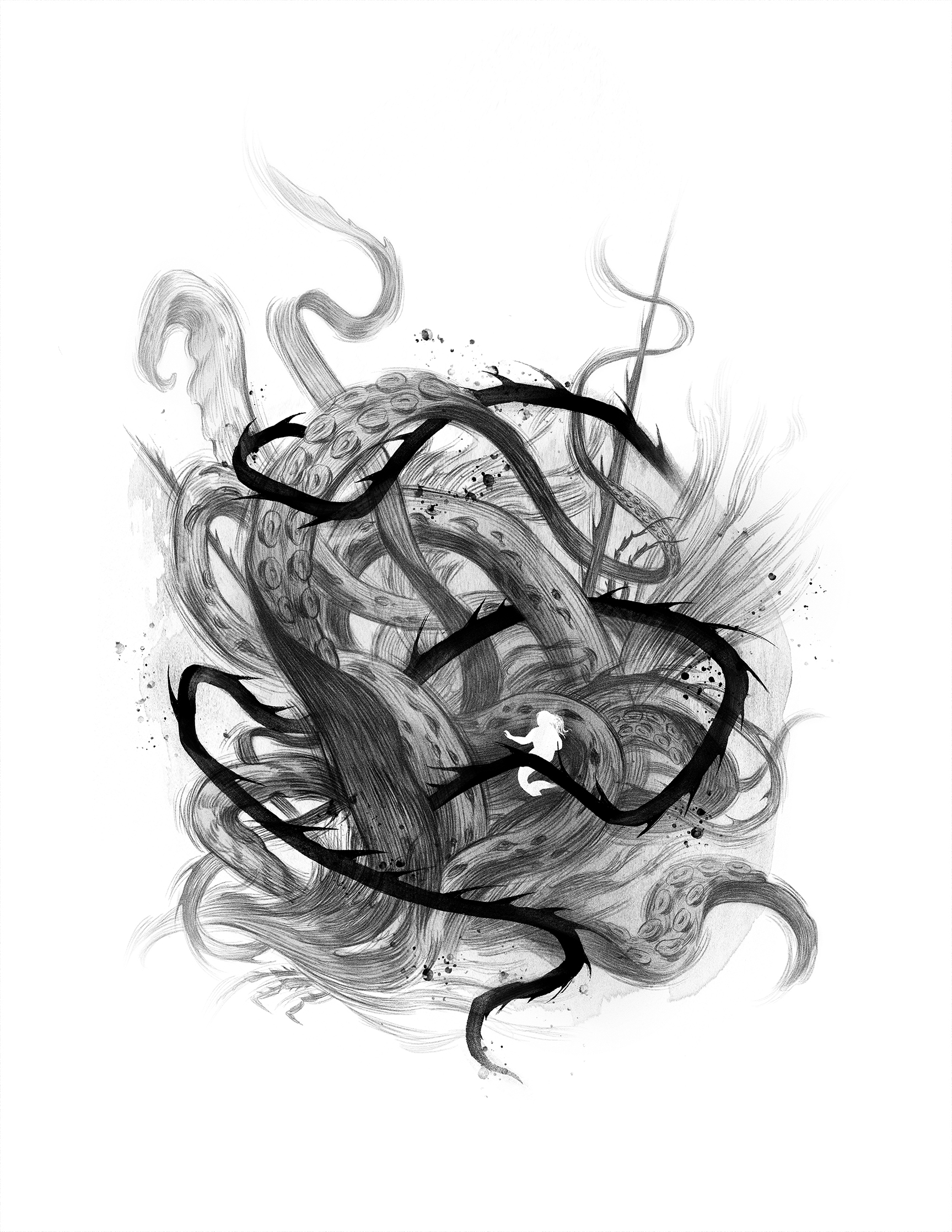

They came as she had seen them in the Moors, unspeakable towers of tentacled flesh, suckers pulsing, surfaces bristling with eyes in a thousand shades of sunset, their pupils like sine curves against fields of red and gold and pink.

“You belong to us, little mermaid,” they whispered. “We gave you back your legs. We gave you back your voice. You belong to us.”

“I do not.” In dreams, Cora had her fins and her scales again, and the lashing of her tail held her upright, as freed from the bonds of gravity as the Drowned Gods themselves. “I fell because you designed the bridge to fall. An animal that falls into a trap may be caught, but that doesn’t make it a possession.”

“We flushed you out of hiding. You are ours.”

“I am not. I refuse.” The water was sweet. Cora inhaled deeply. “The gods of the Trenches and the gods of the Moors aren’t the same. You don’t belong in these currents. Be gone.”

“Not alone.” A tentacle lashed out, wrapping tight around her waist, trying to drag her forward. Cora shook her head, silently refusing to be moved, and try as the Drowned God might, it couldn’t budge her. She hung in the sea like a star.

“I will not,” she said. “I am not yours to cling to or claim. Go back to your own waters.”

Her time at the Whitethorn Institute had weakened their hold on her. She knew that now. In the months of resisting Whitethorn’s pressure to transform her into something else, she had somehow built up her strength to resist the Drowned Gods’ attempts to do the same thing. And their desperation was growing, or they wouldn’t have approached her so directly. She was stronger than they were, here in this familiar sea.

Slowly, the tentacle unwound from her waist. “We will be back.”

“And I will not go with you. Now, or ever. This is not your place.” She took another breath. “I am not your door.”

The eyes of the Drowned Gods slammed shut, taking the light they had cast with them, leaving Cora alone in the dark water. She floated in place, arms spread, hair a skirl around her face. To the silence she repeated:

“I am not your door.” After a pause for thought, she added, “But I might be my own.”

Cora sighed, and stretched, and woke in a cold, white-walled room with a thin blanket wrapped around her legs, binding them together into a child’s approximation of a tail. She kicked once, enjoying the way her industrial cotton “flukes” bounced, and waited for someone to come and let her out.

It was several hours later when she stepped into the dorm room, a matron behind her and her eyes pointed at the floor, so she wouldn’t have to look at any of the people in the room. She was back in her uniform, her hair perfectly combed and pulled back in a neat French twist that wouldn’t have looked out of place in a senior portrait.

“Please remind Miss Miller of how we do things around here,” said the matron. “I trust you can be gentle with her.” She stepped out of the room without waiting for an answer, closing the door as she went.

Sumi, seated cross-legged on her bed, didn’t move.

Emily gasped. “Cora, your hair…”

“I know. Pretty, isn’t it?” Cora lifted her head, smiling like a shark’s fin cutting through still water. There were no rainbows left on her skin. They had all flowed into her hair, which was still blue-green, but now gleamed nacre-iridescent and impossible.

“You’ve been gone for three days,” said Sumi. Her voice was flat. “They only kept me for one.”

“It didn’t feel like three days to me,” said Cora. “I was dreaming for most of it.”

Sumi nodded as if this made perfect sense. “Did they feed you?”

The nameless girl scoffed from her place on the other side of the room. “Of course they fed her. This is a school, not a prison.”

“No,” snapped Emily. The nameless girl flinched, looking startled. “For you it’s a school, because you want to be here. The rules are different for people who enrolled voluntarily. They’re not afraid you’re going to run. This is a prison. You’re just lucky enough not to be able to see the bars.”

“I enrolled voluntarily,” said Cora. “But no, they didn’t feed me.”

“Not like you needed it,” said the nameless girl, forcing the sneer back onto her face like she thought no one would have noticed when it disappeared.

“I bet you’d fit under the bathroom sink,” said Emily pleasantly. “You wouldn’t have a month ago, but now? You look like you’re just the right size.”

The nameless girl paled, clapping a hand over her mouth like she was going to be sick. Then she bolted from the room, presumably heading for the bathroom. Rowena lowered her book and gave Emily a reproachful look.

“That wasn’t kind,” she said.

“She isn’t kind,” said Emily. “It’s not my fault if she can’t take what she dishes out.”

Cora started laughing.

Rowena looked at her with disgust. “No food for three days, rainbows in her hair, and now she’s laughing? She’s dangerous.”

“She can hear you,” said Emily.

“Maybe.” Rowena leaned back against her pillows. “If she starts screaming for no reason, you’ll have to get rid of her. I need my sleep.”

“You’re a monster,” snapped Emily.

“That’s why I’m here,” said Rowena, and went back to her book.

“Why did they keep you for three days?” asked Sumi.

Cora kept laughing.

“They wouldn’t have hurt her, would they?” asked Emily, a nervous edge in her voice. “They’re not supposed to hurt us.”

“Everything about this place is hurting us,” said Stephanie.

Cora choked on her laughter and stopped, falling silent. A single tear ran down her cheek. Like her hair, it was full of rainbows. “I enrolled here voluntarily, but we have to leave,” she said.

Sumi threw her hands up. “Thank the Baker! Now how do we get out of here?”

The door opened. The door closed. The nameless girl leaned against it, putting one more barrier between them and the outside world, and said, “You don’t.”

“Why don’t you go stuff yourself in a hole?” Emily never took her eyes off Cora. “Sumi, you can’t help her plan an escape attempt. She’ll just get us all hurt.”

Rowena slid off the bed, skirting the little knot of damaged, damaging girls to stand next to the nameless girl. “I’m going to get a matron,” she said.

Surprisingly, it was the nameless girl who said, “No, you’re not.”

Rowena turned to stare at her. The nameless girl shook her head.

“The matrons can’t help. If you go to get one now, we’ll all be in trouble.” The nameless girl moved so that she was standing almost nose-to-nose with Cora. Taking a deep breath, she said, “Be ready to grab Rowena.”

“But—”

“Do it.” She looked Cora dead in the eye, and said, “My name is—”

The sound that came out of her mouth wasn’t nothingness, wasn’t blankness. It was static loud enough to drown out the world. It was the howling of the limitless void between universes, and when it was over, Cora blinked, expression going thoughtful as she took a step backward.

“Oh,” she said.

“It was my own fault,” said the nameless girl. “I thought I could handle it.”

“We all make mistakes,” said Cora. She turned to Emily, and a flicker of regret crossed her face. “I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to frighten you all.”

“I still don’t get why they held you for three days,” said Stephanie. “Sumi’s the one who hit Regan, and she came back days ago. Why didn’t you?”

“I yelled at the headmaster,” said Cora.

Everything was silent for a long beat, before Sumi said, “Listen. I was dead once. It hurt. It wasn’t anything, and it hurt anyway, because death doesn’t need to be something to hurt. And then I went to a whole bunch of different places, pulled apart like taffy, and that didn’t hurt until I was together again. It hurts now when I dream. I fought in a war and I won and I lived, and I buried my parents and I broke my brother’s heart and I lived, and I died because a scared child wanted to go home, and I didn’t blame her, because I might have done the same thing if I’d been in her petticoats. She was trying to be clever the only way she knew how.”

Emily looked at her blankly. “Why does that matter?”

“Because the people here think they’re helping us. They think they’re heroes and we’re monsters, and because they believe it all the way down to the base of them, they can do almost anything and feel like they’re doing the right thing.” Sumi rubbed her wrist, almost idly. “They can lock someone in a white room where the light never goes off and say it’s because they can’t have any more illusions. They can not feed you but give you lots of water and no toilet, and say it’s because the real world doesn’t always meet your needs. They can do a lot of things. This isn’t a good place. Even if you’re here because you want to be, this isn’t a good place. This place hurts people. It makes them crawl into their own hearts to be safe, and then it turns those hearts against them.”

There was so much more she could have said, like the way the war was still echoing in her ears, the way she could hear the screams of the wounded and the weeping of the captured. She could have told them about the wisps she wasn’t sure were memories, the little fragments of the Halls of the Dead, her voice hollow and stolen from her mouth, her hands motionless by her intangible sides. Most of all, she could have told them about Sumiko, poor shade, discarded self, who was stirring more and more, because Sumi had been the necessary armor to survive Confection, and Sumiko was the necessary armor to survive the Whitethorn Institute.

She could have. She didn’t. The words were too much and would have distracted from the only thing that mattered.

“We can’t stay here,” she said. “They’ll devour us if we stay.”

“Well, I’m not leaving,” said Rowena. “They hurt you because you wouldn’t listen. You wouldn’t follow the rules. The rest of us don’t have your problems.”

For a long moment, the room was completely silent.

“I am,” said the nameless girl.

All four of the others turned to look at her. Her cheeks reddened.

“I came here because my parents said it would help me,” she said. “I’ve done everything I was asked to do. I’ve followed all the rules, even the ones that don’t make sense, and for what? I’m still shrinking. I still don’t have a name. Anything that starts to feel like a name disappears. Maybe I’m doomed, but I’d rather be doomed in my own room, with my own things around me, than be doomed here, where they make me eat shredded wheat for breakfast and peanut butter sandwiches for lunch and act like cheese is the root of all evils. I want to go home.”

The longing in her voice was complicated and undeniable. She might not know where home was anymore, but she knew she wanted to be there. She knew she wanted to wrap it around herself and let it carry her away.

“You’ll never get better if you run,” said Rowena.

“I’m not getting better now,” said the nameless girl. She looked earnestly at Rowena. “We’re friends, aren’t we? We’ve always been friends. I’ve never asked you for anything. Well, I’m asking you for something now.”

“I’m not running away from school,” said Rowena. “I came here because this is where I need to be.”

“You don’t have run away,” said the nameless girl. “You just have to promise not to tell on us when we do.”

“I want … I want this to matter, but it doesn’t,” said Emily. “You understand that, don’t you? No matter how much we want to leave, we can’t. The doors are locked. The grounds are walled in. We’re all being watched, and that goes double for Cora. We’re here until we graduate, or until our families take us home.”

“That won’t happen,” said Rowena.

Sumi looked at her curiously. She shrugged.

“My first dormmate was this weird kid who liked to say math was negotiable and she could do the calculus at the heart of the universe if we’d give her some chalk. She wrote her parents every week, asking them to take her home. She said all the right things. But they never came for her, and when she finally graduated, her dad said something about how all that silence had been worth it if it meant they got their daughter back. Don’t you understand? They never saw her letters. The matrons control the mail, and the headmaster controls the matrons, and if he doesn’t want us talking to anyone on the outside, we won’t. There’s no rescue coming. You’re here until you graduate. That’s the only way out.”

“And you still don’t want to leave?” asked Cora.

Rowena shook her head. “I like it here. I like the rules and the structure and waking up every day knowing the air will be breathable and the water won’t be. I don’t enjoy having the laws of physics treated like a game of red rover, okay? Some kids get magical worlds full of sunshine and laughter. Me, I got ‘the floor is lava’ from a place that really meant it. I could graduate tomorrow if I wanted to. But out there, in the real world, doors can pop out of nowhere and sweep you away. Out there, the rules can change.”

“Huh.” Cora looked around the room, assessing every line and angle. “You’re right.”

“What?” asked Rowena.

“The rules never change in here. The rules never change at all.” Cora turned back to Rowena. “Be sure. That’s what all the doors say. Everyone I’ve talked to—and people at my old school talked a lot—has said that. Be sure, and if you are, wonderful things can happen to you. Be sure. If I was ever sure in my life, I was sure when in that room, when I told the Drowned Gods I didn’t belong to them. It was my moment of catharsis, and I can’t be the only one. This place is like a psychic licorice shop. A hundred flavors of ‘sure,’ and somehow none of them are enough to bring back the sun, none of them are enough to open a door, for anyone? That doesn’t make sense. Someone’s keeping the doors away.”

“The matrons say we have to give up the idea of going back, because it doesn’t happen,” said Emily uncertainly. “That’s part of why it’s so important we learn to let go of where we went, what we … were. Because even if we don’t, we’ll never get to go back.”

“Lots of people go back,” said Sumi. She waved a hand, like she was trying to brush away a particularly unpleasant smell. “Not everyone. Most people can’t be entirely sure they’d be happier in one place over another, so they don’t find their doors again. But lots of people go back. They have the right combination of selfish and lonely and hopeful and stupid and earnest and selfless, and they find their doors, and they go back. There’s more students here than there are at Eleanor’s. Someone should be able to find their door. If no one can, what does that say?”

“What does it matter what that says?” asked Stephanie. “If they’re being locked, they’re being locked. We don’t have a key.”

“Sometimes you don’t need a key,” said Sumi. Her smile verged on feral. “Sometimes a crowbar is good enough.”

“I have a plan, I think,” said Cora. “But I’m going to need you to work with me—even you, Rowena. You don’t have to come with us, but you have to be on our side.”

“What do I get out of it?” asked Rowena.

“We leave,” said Cora.

Rowena thought for a moment. Then she nodded. “All right,” she said. “What do I have to do?”