GRAMMAR (SYNTAX)

Grammar is the study and the formulation of how words relate to one another in a sentence. Consider the non-native attempting to speak English:

“Please…fish…little…cost…good…thank you.”

The foreigner doesn’t know English grammar. He or she has learned some words but not how to put them together. When the speaker develops his/her language skills, he learns to make connections. He doesn’t have to cover his heart with folded hands, drop to his knees, and look longingly with his eyes only. He can say: “I love you.” To a native speaker, this sentence seems so “natural,” what else could it be? Well, if you were a Roman, the verb would come last, and there would be no separate I. In some languages, the three words would be one word alone. In short, there are more than six thousand human languages that we know of, and all of these have different ways of relating words to each other; all have different grammars.

Remarkably, by the time children are three years old they have “learned” the grammar of their native languages. However, like the fish who takes the water it swims in for granted, unless we study our language, we may be unaware that the connections we make are not natural, nor are they given. Rather, we have absorbed a human-made system.

We speak and write our language following rules about how the words and phrases can be strung together. Grammar or syntax is the collection of rules that describe how to connect words, what goes next to what, in which order. To communicate what’s inside our heads or hearts to another, we need to know what does, what can, and what words and phases can’t go together.

Functions: In addition to rules of relationship, grammar also identifies what the different parts do, or their function. Let’s examine the sentence:

Jack looked at Jill lovingly.

Jack is the subject. That is, the function of the word Jack is as doer of an action. Looked is the action that Jack did. We call such action words verbs. Jill, unlike Jack, is “the done to.” Jill’s function is as object, not subject. Then, take the word lovingly. This word functions to describe the verb/action (how did Jack look?). Lovingly is functioning as an adverb, a part of speech we will soon discuss.

The words and groups of words in any sentence are identified, then, by their function, the way the players in a baseball game are identified. Ted Williams may be the batter at one time, and at another, an outfielder. It depends on what function he is performing. So, too, a word can play various functions depending upon how it relates to other words in a sentence. In the example above, look is an action verb, what Jack did. However, consider the difference: The look of love is in your eyes. In this case, look is a noun and subject of the sentence.

EIGHT PARTS OF SPEECH: DESCRIBING THEIR FUNCTIONS

English grammar is built upon the interrelationships of eight functions, or parts of speech: nouns, pronouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, voice, prepositions, and conjunctions. These are described and studied in this section. We will also identify the grammar and punctuation problems that often occur with parts of speech. Some of these problems are discussed again in other sections.

Nouns

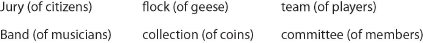

Nouns name people, things, places, animals, items that have shape and form, things we can touch. Things, however, can be less tangible and refer to abstractions such as ideas of freedom, independence, or concepts such as number and shape, or disciplines such as the sciences, the arts. Some nouns name groups of persons or things.

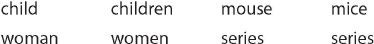

Number: nouns change in number—they can be one (singular), or more than one (plural.) Most nouns show this change in number by adding an s. One boat becomes two boats. However, some nouns show number change differently. One woman doesn’t become two womans, rather, she becomes two women.

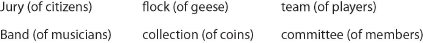

Collective nouns often cause difficulties because of number. They can be confusing because they refer to something made up of more than one.

But grammatically they are treated as singulars, as its rather than theys. For instance, “the team played their last game” is grammatically incorrect and should be “the team played its last game.”

Types of Nouns

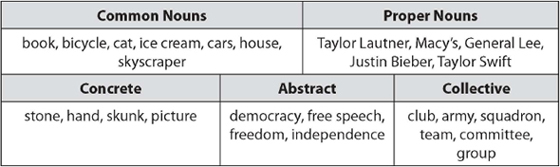

Noun Case: What do nouns do? First, the subject of a sentence is always a noun, as was Jack. But nouns can also be objects, as was Jill (the receiver of the verb’s action). Or, in their Possessive Case form, nouns are expressing belonging to, or a quality of. Case, then, means the function a noun plays in relationship to other words. There are three cases, and we will see the same when we examine pronouns.

Types of Noun Case

Note, however, we can rearrange these nouns—depending on what we want to say—changing their function and their case, like moving Ted Williams from the outfield to first base:

The mouse escaped from the cat.

Now, our rodent is the subject, and our cat is the object of the preposition from. And we mean something different from our first sentence.

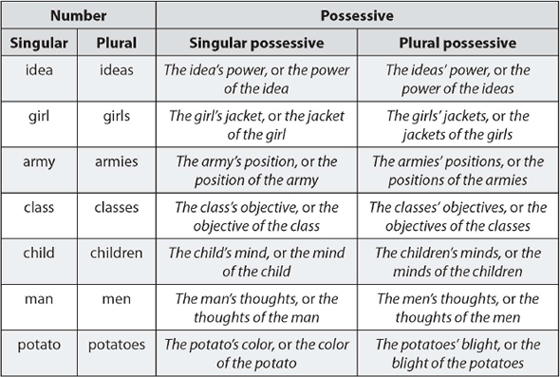

Note, too, the noun in the Possessive Case indicates ownership by use of apostrophe (‘) and the letter s: The cat’s prey instinct made him constantly hunt for mice. (whose instinct? The cat’s). Or, The girls’ dates were all waiting for them outside in the schoolyard. (Whose dates? The girls’.)

Pronouns

Pronouns stand in for a noun and give us ways to substitute for nouns, and thus we can speak with fewer and shorter words and phrases, and with greater variety! Consider what we would face without pronouns:

Jimi Hendrix is well-established in the history of music. Hendrix is the King of Rock, and Hendrix’s guitar playing is legendary. Jimi Hedrix’s death by an overdose made Hendrix an icon of the 1960s. Like Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix was the image of overindulgent youth.

Now, with pronouns:

Jimi Hendrix is well-established in the history of music. He is the King of Rock, and his guitar playing is legendary. Jimi Hendrix’s death by an overdose made him an icon of the 1960s. Like Janis Joplin, he is the image of overindulgent youth.

Antecedents: Because a pronoun substitutes for a noun, when one is used, the noun for which it is substituting has to be clear. For example, the pronoun he only communicates if we know the noun for which he is substituting. An example would be: He died by assassination. This sentence without a reference to which the pronoun is referring, makes little sense. However, the following sentence clears up any confusion:

Abraham Lincoln is a symbol as much as he is a former President. He died by assassination.

Now, the pronoun he is comprehensible because we have the antecedent noun for which it is substituting: Abraham Lincoln is he.

Antecedent is a term you will see in several important language situations. It means that which comes before. In the case of a pronoun’s antecedent, it is the noun to which the pronoun refers. Every pronoun has its “Abraham Lincoln,” if it is being used clearly! A clear and consistent relationship between the pronouns and to what or to whom it refers (antecedents) is a major grammar concern called Pronoun Agreement (A2 = Antecedent + Agreement).

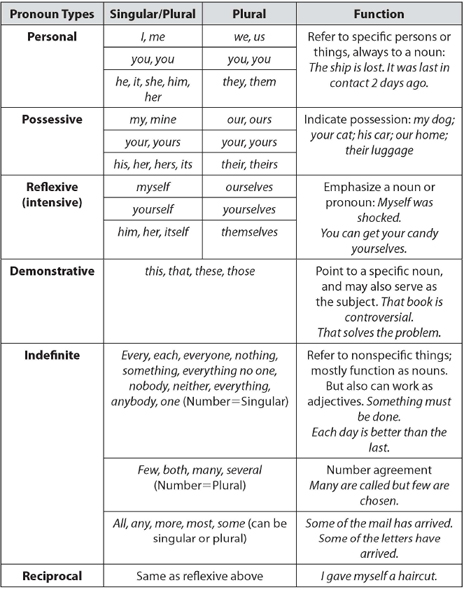

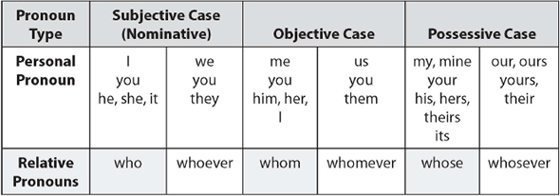

Pronoun Types & Cases: In the examples above, we have used different forms of pronouns (he, him, I, and me), so let’s give these differences a name and description. The most frequently used are the Personal Pronouns. But glance at the left column in the table below to view the eight various types of pronouns.

Pronouns: Their Number and Function

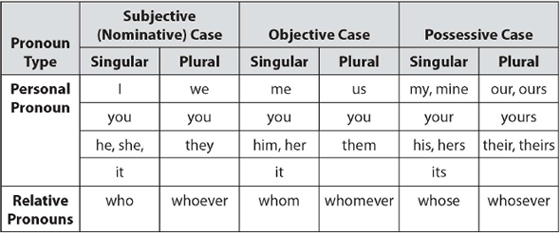

In addition to the eight types, pronouns—like nouns—have three cases. Recall, case refers to function in relations with other words. For instance, the personal pronoun I is the Subjective Case since its meaning (the doer, the subject) also puts it in a specific relation to another word, a verb:

I gave my ticket away.

I, however, has different meanings and relations with verbs and these differences are expressed by case. Thus, when I is not the doer/subject of the verb, it may be the done to and object of the verb. When this occurs, the pronoun I changes its case to the Objective Case and becomes me.

John gave me his ticket.

Personal and Relative Pronouns

Notice, too, his, which expresses belonging, is in the Possessive Case. Only two of the eight pronoun types have the case form or aspect. Unlike nouns that show possession by adding an apostrophe s, or by changing their ending (e.g., woman to women) pronouns in the possessive case remain unchanged. The relative pronouns bring up an important topic. That is, how we speak is sometimes different from how we write. In speech, we are allowed to be ungrammatical. For instance, many, perhaps most of us, would ask: Who did you go to the movies with? But this is not correct. Who is not the subject, you is the subject. It is the object of the preposition with; hence, the question needs the objective case: Whom did you go to the movies with? Again, like nouns, pronouns are either singular or plural.

Verbs

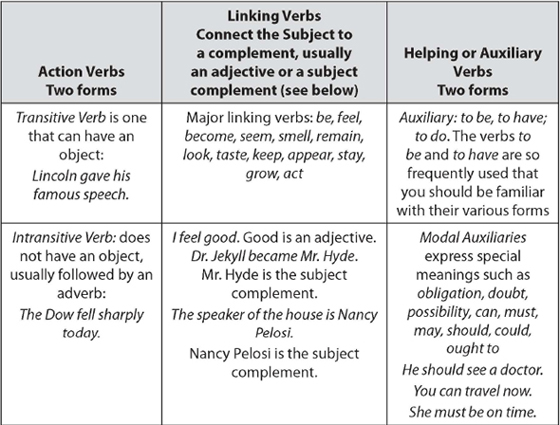

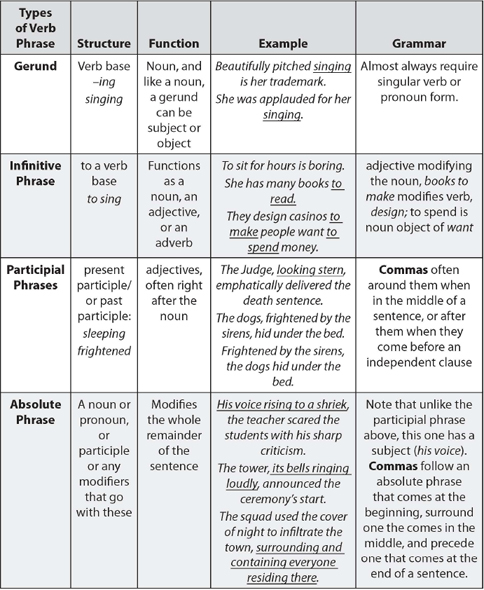

Verbs are where the action is! The cannibals ate their victims. The action verb is eating. Another kind of verb doesn’t so much describe an action, but rather it connects, and is called a linking verb. For example: Jack seems excited to have gotten that telephone call. Seems is a linking verb; it doesn’t describe an action such as eating, or traveling, or snoring. It does connect Jack to excited, and in making this link, it tells us something about Jack.

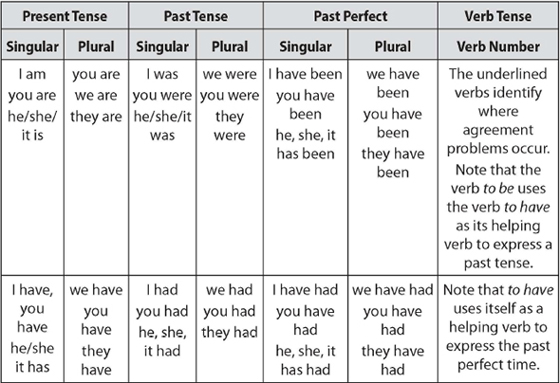

A third kind of verb is called a helping verb. These help another verb—which is the major one—to express a nuance, often a time aspect of the main verb. For instance: I am going to the movies. Going is the real action, the main verb; am is helping by giving going the sense of in process. Or, consider this sentence: I had seen her before she saw me. Seen is the main verb (act of seeing); had is its helping verb. It expresses that the seeing was done earlier, before she saw me. In fact, to be and to have are the most common, frequently used helping verbs, and they are used primarily to indicate verb tense as you will see below. However, there are other, less common helping verbs, and there are a few more things to be said about active verbs, so let’s examine this table below before moving on to verb tenses.

Types of Verbs

Grammar Highlight: Action verbs usually are followed by adverbs; but linking verbs are followed by adjectives. Because of how they sound in speech, modals with have are often incorrectly written as of: The car must of run out of gas. Which should read: The car must have run out of gas.

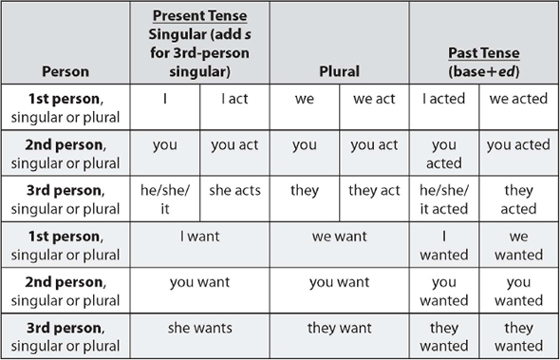

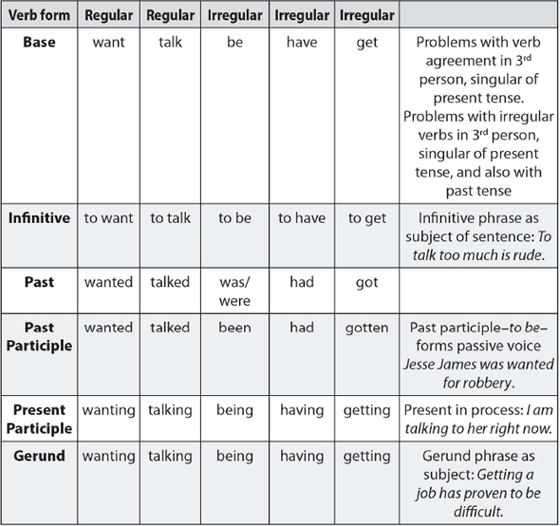

Verbs have various forms. Identifying these helps us understand the various ways a verb is used. Right from the start, we need to know how to distinguish between the two forms. Regular verbs follow the same general pattern: add -s on to the verb base to form the 3rd person, singular in present tense. Past tense adds -ed to the base verb. Irregular verbs are stubborn individuals who follow their own patterns (irregular verbs). Consequently, since the irregulars are individuals who dance to their own tune, we cannot apply rules to them, but have to learn them as individuals. Irregular verbs change either the 3rd person singular, or the past tense, or both, and some verbs like to be make unique changes in other persons and tenses (see lie, lay, rise below).

Look at the tables above where both to be and to have, irregular verbs, can be studied and contrasted with regular verbs. All regular verbs follow the same pattern in 3rd person singular and in past tense.

Verb Person

Verb Person: which of the three available is doing the action or linking? Is it the 1st, 2nd, or the 3rd?

Number: as with pronouns, how many? One, or more than one? Singular or plural?

Verb Tense

Verb Tenses: Verbs also change according to the time of their action or linking. These time changes are called tenses. Consider how tense adds to our ability to communicate with one another. Imagine, for instance, arriving at someone’s house who, being a generous host, offers you lunch. We take for granted that it’s a simple matter to decline without offense by explaining: No, thank you, I ate lunch but an hour ago. If we had no past tense, we would be forced to act out and hope to be understood, perhaps by: “I eat…” and then indicating past by gesturing behind our shoulder with our hand.

In writing, we dramatically alter the meaning of what we say by our use of tense:

I was studying when the lights went out and threw the dorm into darkness for the rest of the evening.

I had already studied when the lights went out and threw the dorm into darkness for the rest of the evening.

Present Tense: actions occurring now, actions occurring regularly, or general truths:

I see you sitting there; every day.

I speak to the homeless man.

Love is stronger than hate.

Past Tense: Actions that happened before now and are over and done with:

I ate dinner an hour ago.

Future Tense: Action that will happen in the future:

I will eat dinner within the hour.

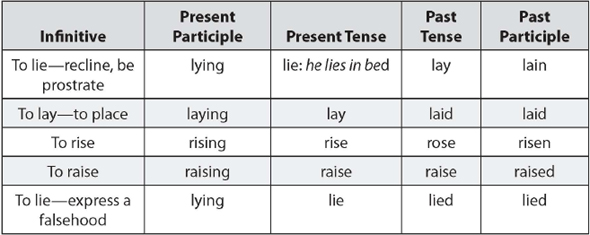

Finally, there are a few verbs that give people trouble such as the differences between the verbs to lay and to lie, or those between raise and rise.

Irregular Verbs-To Lay, To Lie or To Rise

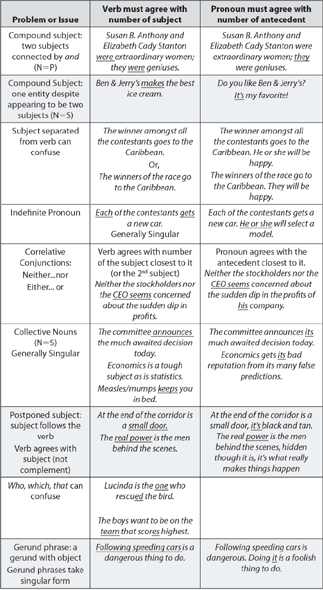

Subject Verb Agreement (agr): Speaking trains native speakers to follow this rule quite ‘naturally’; however, there are some grammatical structures that give many writers problems. First, let’s look at the typical sentence and how the law of agreement works:

Yesterday the children ate their lunches at their desks.

The verb must agree with the subject’s person and number. The subject is children; its number is plural and its person is the 3rd (see chart above). Now it’s true that the writer also had to know the correct past form of the verb eat which is ate and not eated, and also the correct tense.

Most agreement problems have to do with number, which means determining if the subject is singular or plural. Indeed, verb agreement with subject is very similar to pronoun agreement with antecedents, and the chart below will help this.

English strongly prefers that the subject come first, followed by the verb, then by the object or recipient of the actions, or, if a linking verb, by a subject complement or an adjective.

The batter hit the ball hard.

the ball hard.

The Academy of Film Arts gave Julia Roberts an award.

Julia Roberts an award.

This pattern with the subject going toward (with the verb) the object (formula, S+V+O) is the Active Voice.

However, writers sometimes (correctly, often incorrectly) use the Passive Voice. This reverses the formula, O+V+S, making a sentence with the object of the verb first, then the verb, and finally, the subject.

The ball was hit hard by the batter.

batter.

The action is turned around, the subject, batter, fades and the focus is on the object, the ball. In short, the passive voice puts the object in the limelight, and it weakens both the act (the verb action) and the subject (the doer). By contrast, then, the active voice highlights the subject and emphasizes that she/he is the doer. So, when is it correct to use the passive voice? Answer: when the object is more important than the subject. Consider:

Natalie Portman was awarded an Oscar for her performance in The Black Swan.

Or in the active voice:

The committee awarded Natalie Portman an Oscar.

The first sentence is preferred because the fact that Portman won the Oscar is more important than the committee that did the awarding. Now let’s examine the structure of that passive voice: Natalie Portman is the object, was rewarded, the verb, and the subject has so faded from importance that it isn’t even in the sentence!

Was rewarded also shows us the formula for a passive voice verb = to be + past participle.

The Mona Lisa is considered a Renaissance masterpiece by most art critics.

Is (to be) considered is the past participle of consider. In this case the doer is nowhere to be seen. A much stronger, active sentence is:

Art critics consider the Mona Lisa a masterpiece.

Here’s another case: This is to inform you that your application has been rejected. By who? As a rule, the active voice is the most effective, and it’s always more concise and less wordy.

While in a few instances, using the passive voice is fine, and, more rarely still, preferred, in the vast majority of instances, the passive voice is discouraged for two good reasons: the passive voice is weaker because the subject as actor is backstage—if present at all, in the rear rather than up-front. Thus, “the action” is muted and diluted. The passive voice is more wordy—always. Count the words in the two sentences above. Count them in the two following sentences:

Active: The instructor discussed the requirements and the time schedule for this semester’s class.

Passive Voice: The requirements and the time schedule for this semester’s course were discussed by the teacher.

Adjectives and Adverbs

Adjectives are words that describe nouns or pronouns. We use adjectives a lot in speech and writing; many common ones pepper our conversations. For example: a good day; a soft sound; a yellow car.

Adverbs have more possible roles than the adjective. Adverbs can describe verbs (he spoke slowly); they can describe adjectives (His face had a sickly yellow look. She is very sad.); they can describe adverbs like themselves; they can describe infinitives (he was urged to go quickly.)

Adverbs often answer the question how? How did he go? Quickly.

Adverbs often end in -ly: quickly, smoothly, sleepily, coldly

Those adverbs that don’t end in -ly are often those that refer to time and frequency:

today, yesterday, often tomorrow, soon, never, always, never, sometimes

Grammar Highlight: Remembering that adjectives modify nouns, and that, contrarily, adverbs modify verbs, adjectives, or another adverb will help you to identify what a prepositional phrase is doing in a sentence.

Prepositions

Your teachers may have advised: “Never end a sentence with a preposition!” But what’s a preposition? We use them very frequently (look at the list below), but defining them clearly is difficult. Prepositions, for instance, are words that connect a noun to other parts of its sentence. Or, prepositions are words that express space (on the table), time (at the appointed hour), and direction (towards the North Pole). There are two kinds of prepositions—simple, one-word prepositions, and group prepositions.

It’s easier to get a handle on the simple, one-word prepositions by identifying them in the prepositional phrase (where they most often are to be found, except when they end a sentence by themselves!). You will find the preposition before a noun or a pronoun, and it will almost always be working as an adjective or an adverb, modifying a part of the sentence of which it is itself a part. Here are the most common:

above, behind, except, off, toward

above, below, for, on, under

across, beneath, from, onto, underneath

after, beside, in, out, until

against, between, inside, outside, up

along, beyond, into, over, upon

among, by, like, through, with

around, despite, near, throughout, within

at, during, of, to, without

Group prepositions are made up of more than one word:

in addition to |

in place of |

next to |

in front of |

as well as |

along with |

according to |

due to |

in conjunction with |

because of |

Infinitives: The word to is one of the most used prepositions. When you find it, you are fairly sure that it is the first word in a prepositional phrase. However, another important construction using the word to is the verb infinitive, the base of a verb preceded by to. Infinitives: to go; to see; to believe; to investigate. All verbs have this simple infinitive form.

In a sentence, the infinitive can be a noun, both subject:

To read is heaven on earth to Julia.

or an object,

Julia likes to read.

An infinitive can be the subjects complement:

It is the responsibility of all expert detectives to investigate a crime for as long as it takes.

Conjunctions come in four basic varieties. They work to join parts of sentence, to join together words, or phrases, or clauses, or even sentences. And is probably the most used conjunction—observe how frequently we use it to join words: apples and oranges; work and play; sing and dance; toys and hobbies; Bill and Sally.

And is also one of a group of coordinating conjunctions: for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so, otherwise know as FANBOYS. We’ll use that term throughout the appendix when we refer to these coordinating conjunctions. These FANBOYS help create compound sentences, and when they serve this role, a comma comes before their use.

Correlative conjunctives: Remember these by their “relatives.” These are twins such as neither/nor, either/or, not/only, but/also, both/and.

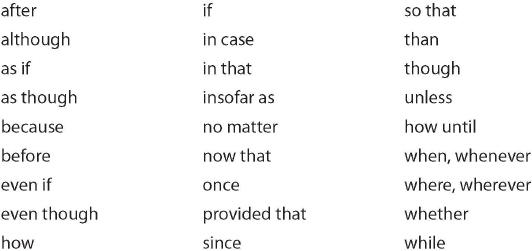

Subordinating conjunctions are

Conjunctive adverbs—make brain connection with semi-colons and commas.

however, then |

She went to the film; however, I didn’t go. |

therefore, hence |

It rained hard and fast; therefore, we stayed home. |

also, consequently |

The book focused on a popular topic; also, its central character was controversial. |

The importer pays the taxes, then sells the articles at an inflated price; thus it is the consumer who ultimately pays. |

Interjections: These are odd-balls in that they almost contradict our definition of a part of speech as defined by its function to other words. This is because they do not really function in relationship, but rather stand outside the grammatical connections. An interjection is strong expression, a powerful emotion, a cry from the soul that sometimes is barely a word:

O Heavenly Father, help us in this time of hardship!

Oh, she cried!

Yikes!

Help!

When we spill over in exasperation, we are likely to express ourselves in interjection:

oh hell; fine; drop dead; scram

Articles: These are so numerous in speech and writing that we want to give them a special focus even though they are not one of the eight parts of speech. A, an, the: Meet the articles—they always come before a noun. General vs. specific noun: A or a functions to identify a noun referring to something in general: a book; a door; a cat. The functions to identify or point to a specific: the book, the cat, the door. Spelling articles: a is used when the noun it identifies starts with a consonant: a book, a door, a cat. An is used when the noun starts with a vowel: an elf, an apple, an ice cream cone, an ox, an ulcer.

THE SENTENCE

The previous section reacquainted you with grammar or syntax: the laws of relationships and the function of the components of English, the eight parts of speech. This section focuses on the sentence: what it is (definition); what it does (function); what it’s made of (structure and criteria); its four forms (meanings), its four types (variations in structure); and the punctuation that sentences use to fulfill their function: to express a thought! In this section we will also identify the major grammatical and punctuation problems related to sentence structure.

What defines a sentence? Basically it is a complete thought—that is, it’s a grammatical unit that is composed of one or more clauses. Clauses are units of words that form a complete thought. The function of a sentence is to express an idea, a fact, or a desire.

Examples: |

I want an ice cream. |

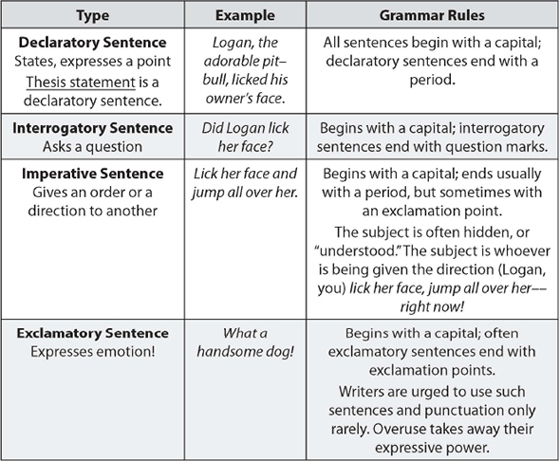

Sentence Function

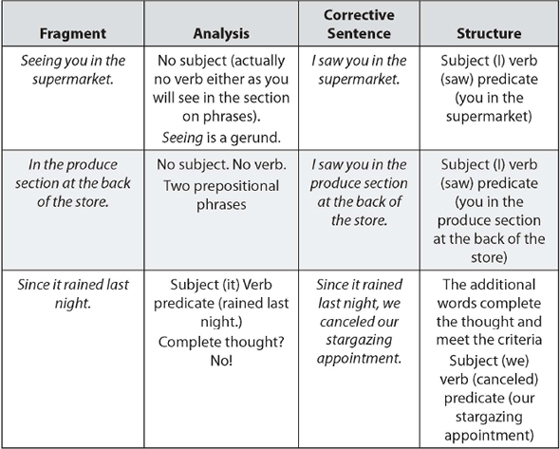

As we speak, the listener knows when our thought is complete by our inflection, by the tone of our voice, or by our body language. In writing, two signals “tell” the reader: “Mission accomplished!” The capital marks the start, the ending punctuation (period, question mark; exclamation point) in effect, says, “I’m done.” When we incorrectly give the signal telling the reader that we are finished, but it isn’t a complete thought—we cause confusion. This signal malfunction creates a sentence fragment. To qualify as a sentence, and earn its punctuation marks, a group of words must meet three criteria:

1. it must have a subject.

2. it must have a verb (and often has a verb predicate, verb + other words).

3. It must be a complete thought (this is the criteria that a fragment does not meet!).

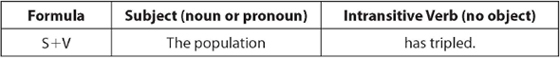

Sentence Patterns

English sentences tend to fall into patterns, and be represented as formulas. The following are the major ones.

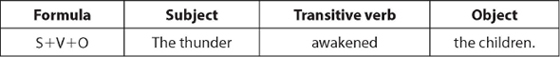

Pattern 1

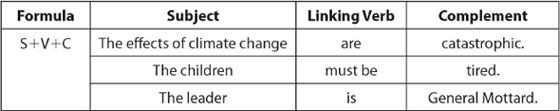

Pattern 2

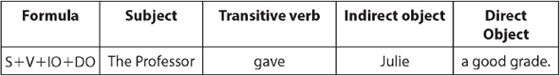

Pattern 3

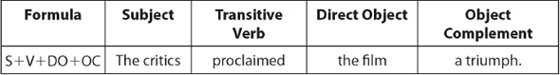

Pattern 4

Pattern 5

Simple Sentence: “Simple,” in this case, doesn’t mean short, nor does it mean that it is non-complex. Rather, it refers to its structure—to what its parts are. A simple sentence can be very long, but it will have only one independent clause.

Independent Clause: is a synonym for sentence. Another way of saying this: A sentence is an independent clause, or it is made up of more than one independent clause. Whenever you come across the phrase independent clause, think—it meets the three criteria for a sentence. We’ll examine clauses in the paragraphs below. Here is a short simple sentence.

Proust and Gide are the best known French writers of the 20th century.

Here’s another a little longer.

Both Proust and Gide wrote for a 20th century audience and yet retained their relevance for readers of the 21st century.

And longer still:

In the end, against our wishes, in opposition to all advice, our son, John, and the neighbor’s daughter, Janice, dropped out of school, left all their friends and family, and embarked on a trip across country despite the poor weather and the high cost of fuel.

Note: the underlined sections identify the skeleton of the one independent clause: compound subject and compound verb (three of them). The rest of the sentence is primarily prepositional phrases.

Compound Sentence: is one that has more than one independent clause, and no dependent clauses.

Examples:

The children baked three pies, and they took all of them to the patients.

Barack Obama began the presidential campaign of 2008 behind Hillary Clinton, but he still managed to win.

Look closely at each of the underlined sections. Think back on the sentence pattern. Identify how each has a subject + verb predicate, and each is a complete thought. Therefore, each of them could be a separate sentence. As the examples demonstrate, compound sentences connect independent clauses into one sentence, rather than allowing them to stand alone. They do this in two ways only:

1. With a coordinating conjunction (FANBOYS = for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so), and, as the two sentences illustrate, a comma before the coordinating conjunction.

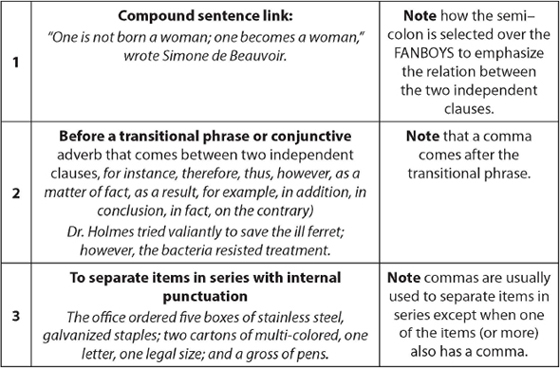

2. Compound sentences are also linked with semi-colons.

The victor is the quickest; Jane Levin’s the sure winner! Or:

Wealth is often coarse; poverty is frequently refined.

Grammar Highlight: a common comma error stems from not differentiating between the and connecting two independent clauses (requiring a comma) from the and, or, but, that is connecting a compound verb (no comma):

John scored well below his average level of performance, but he still passed the test. (Compound Sentence)

John scored well below his average level of performance but still passed the test. (Simple sentence with one subject, John, and a compound verb: scored/passed)

When do you choose a FANBOYS connection, or the semi-colon? The semi-colon is often used to pull the two independent clauses closer together for dramatic effect. Consider the dramatic difference between these two sentences:

John studied hard, but he still failed.

John studied hard; he still failed.

Or imagine how much less dramatic with a FANBOYS:

He came; he saw; he conquered.

Grammar Note: Linking two independent clauses is generally the only correct use of a semi-colon in the middle of a sentence. When you see a semi-colon, check on each side for a sentence that could stand alone. Other, less frequent semi-colon use is to separate items in series, when the items have internal punctuation.

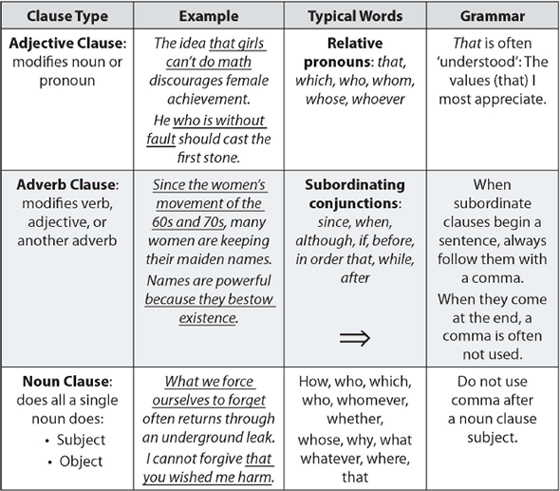

The next sentence type is the complex sentence. They contain one independent clause plus one or more dependent clauses (IC + DC, or IC+DC+DC). Let’s look at a complex sentence with more than one dependent clause:

When the ship comes in, he will get a handsome paycheck even though he never lifted a hand in actually delivering the goods to port.

This combination of one or more dependent clauses in a sentence with an independent clause forms a complex sentence. Let’s examine how dependent clauses in a complex sentence function:

Linguists have discovered at least three ancient languages.

This is a simple sentence: one independent clause. However, we change it to a complex sentence by adding a dependent clause:

Linguists have discovered at least three ancient languages that may be the origin of all others.

Complex-compound sentences are made of at least one dependent clause (making it complex) and two or more independent clauses (making it compound):

Because Gene has always been a big eater, no one was surprised at his obesity, and his congestive heart diagnosis also came as no surprise.

The underlining identifies the two independent clauses. The phrase in bold is the dependent clause. It’s not the length of the sentence but its structure that makes it compound-complex sentence-at least two independent clauses plus at least one dependent clause (2 IC+DC). Here’s another example:

Since Susan B. Anthony was such a staunch proponent of justice in the long struggle for women’s suffrage, the U.S. Postal Service finally, and justly, issued a stamp in her honor; we can only hope that such recognition will follow quickly for Elizabeth Cady Stanton; after all, Stanton and Anthony were indivisible beings, in a partnership that transcended space.

The underlining identifies the three independent clauses; the bold identifies the three dependent clauses that make up this compound-complex sentence. Note that the dependent clause adds more information to the complete thought of the independent clause. This addition of more information is called modifying.

Since Susan B. Anthony was such a staunch proponent of justice in the long struggle for women’s suffrage, the U.S. Postal Service finally, and justly, issued a stamp in her honor.

Clauses

Let’s begin our discussion of clauses by examining the simple sentences from the vantage of clause language:

Proust and Gide(A) wrote(B) for a 20th century audience and yet retained(c) their relevance for readers of the 21st century.

Proust and Gide (A) are the subjects, a compound subject because it has more than one actor.

(B) and (C) are the clause’s compound verb. Both wrote and retained belong to the subject, Proust and Gide. Take away all the other words, and you see the skeleton pattern (S+V) clearly: Proust and Gide wrote and retained.

Grammar Highlight: Comma errors often occur in sentences with compound verbs. The writer mistakenly places a comma before the and, thus separating the verbs that must, for clarity, remain together. Consider this sentence:

Dublin, the awesome pit-bull who lives down the street, habitually barks at, and chases cars.

The sentence reads much smoother if we take out the comma after barks at.

Dublin, the awesome pit-bull who lives down the street, habitually barks at and chases cars.

Let’s examine a sentence with a simple subject (one) and a simple verb (only one):

In the afternoon, after our long hike, we took a very long nap.

We is the subject; the underlined words are the verb predicate (S+VP). It is a complete thought. This is a simple sentence. The words indicated in bold are two prepositional phrases.

Summary: An independent clause is a group of words that has a subject, a verb, and is a complete thought. Since it meets all the criteria of a sentence, it can be one! It’s independent, then, because it is capable of standing alone as a sentence—with a capital and an ending punctuation. However, as in compound sentences, independent clauses are sometimes connected, so that there are two, or three, or even, four, or five of them in one compound sentence.

Dependent Clause as the name suggests needs “someone to lean on” because even though it has a subject and a verb, it does not meet the 3rd criterion of a sentence: it is not a complete thought!

Whenever a new discovery is made. (S= discovery, V= is made.)

But, what happens when a discovery is made?

If we go to church. (S=we, V=go)

Yes? What if we go to church?

In fact, in their current formation (incorrectly telling the reader they are sentences with the capitals and periods), they are sentence fragments. However, we can use them if we complete the thought:

Whenever a new scientific discovery is made, society inevitably benefits.

Look at the description of dependent clauses below to see the different ways that dependent clauses add information to, or modify their independent partners in a complex sentence.

Restrictive and Non-Restrictive Clauses, Misplaced Modifiers, and Parallelism

Identifying the grammar problems of these three issues depends greatly on the ability to identify the clauses we have just studied. These three are also very frequent problem areas for students, so understanding them is especially important.

Identifying the difference between restrictive and non-restrictive clauses will also tell you when to use that and which. Restrictive clauses are necessary to the sentence’s meaning therefore use that. Non-restrictive clauses are not necessary to the main meaning so you would use which plus commas. Here is a complex sentence with restrictive clause underlined:

The poet who served as England’s Laureate throughout Victoria’s reign was none other than Alfred, Lord Tennyson.

Why is that clause necessary to the meaning? Because if we did not have this information, we wouldn’t know which poet is being discussed. Here’s another example of a restrictive clause in a complex sentence:

The buildings that are scheduled for demolition are marked with red paint.

Try taking that restrictive clause out. Note that without the information in the restrictive clause, one cannot identify why the buildings are painted red and, therefore, cannot identify which buildings need to be removed.

Non-restrictive clauses add some information too, but their information is not vital to the main point of the independent clause in which they are embedded:

John Wilkes Booth, who was an actor, shot Lincoln in a theatre in front of the players and the audience.

The commas tell the reader: here’s a bit of interesting information. But knowing that Booth was an actor is not necessary to the main meaning—that he shot Lincoln in full view of the audience and actors. Here’s another to reinforce that which is preferred over that in a non-restrictive clause:

Lost, the television series, which was created five years ago, won three prizes at last night’s award ceremonies.

In the examples below, which is selected to head the clause in the second sentence because the clause gives the reader additional information. Unlike the first sentence, the information does not alter the meaning, nor is the correct understanding of the sentence dependent upon it.

The revolution that dramatically changed the form of Russian society began in 1905 with a bread strike.

The Russian revolution, which to this day has worldwide reverberations, began in 1905 and dramatically changed Russian society.

Who, whom, whoever, whoever are often confusing to writers. The key to using them correctly is pronoun case. Review the pronoun case chart previously displayed in the chapter. Who and whoever are subject case and whomever and whom are object case. Remember, too, that in speaking we commonly are ungrammatical. It’s ok in speaking, but not in writing!

Who killed Abraham Lincoln and altered American history?

Ask yourself what is the subject of “killed and altered”? It is who and thus the choice is correct.

To whom is much given and thus is much expected?

In this case the presence of the preposition, to, would require the objective whom. In addition, to whom is the indirect object of the verb given.

The law decreed that whoever violated the letter would be exiled forever. (Who violated the law?)

The book would belong to whomever won the spelling bee.

Phrases

Phrases look different from clauses—they do not have both a subject and verb. And, they do not determine sentence type as do the presence of independent and dependent clauses.

Major Types of Phrases

1. Verbal phrases (those made with various verb parts).

2. Prepositional phrases

3. Appositive phrases

Verbal Phrase. A verbal phrase uses a form of verb but the new form doesn’t function like a verb (to show action, to help, or to link). Instead, depending on the type, they function as nouns, adjectives, or adverbs.

Prepositional Phrases begin with a preposition and they end with a noun. In the sentence below the underlined words are all prepositional phrases. But note that to buy is an infinitive—to with the verb buy.

All of the children ran to the corner store to buy candy for the movies.

Prepositional phrases are always working as either an adjective or an adverb. Prepositional phrases that are functioning as adjectives are almost always right after the noun or pronoun they modify. Ask the question after all (indefinite pronoun) what? Or after candy (a noun), which candy? The candy for the movies answers the question. On the other hand, to the corner store modifies the verb ran; its functions, then, as an adverb, answering the adverb question, Where did they run?

Grammar Highlight: Remember that adjectives modify nouns, and that, contrarily, adverbs modify verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs. They will help you to identify what a prepositional phrase is doing in a sentence.

Appositive Phrases are nouns that describe another noun or pronoun.

Abraham Lincoln, the 16th President of the U.S., is considered by many the greatest of our leaders.

What makes this a phrase? First, it’s more than one word; second, the main definition or defining word is the noun, President. Appositive phrases nearly always require commas. If one comes in the middle, then commas are placed around the phrase.

American track-and-field athlete Jesse Owens, the winner of four Gold Medals at the 1936 Olympic Games, was a black man.

If one comes at the beginning of a sentence, then the comma follows.

A big thief without a doubt, Madoff deserves life in prison.

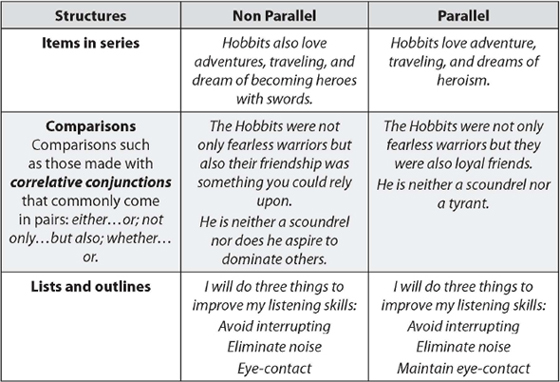

Language shares much with music, beginning, of course, with its basic reliance upon sounds and being heard. Parallelism requires that elements in a sentence that are in series or that are being compared or contrasted be expressed in the same grammatical and syntactical form.

Let’s look at parallelism in series construction: it’s only a hop, skip, and jump away. All three items are nouns, and this makes the sentence flow. Contrast the effect of violating parallelism: it’s only a hop, skip, and jumping away. The switch from a simple noun to a gerund phrase sounds awkward and it confuses the meaning. Consider, again, the difference:

Government of the people, by the people, for the people.

Perfect parallelism such as this is a masterful rhetorical style. Note that each item in the series is a prepositional phrase. In contrast to:

Government of the people, by the people, and with the needs of the people foremost.

Changing the 3rd item of the series from one prepositional phrase to two alters the rhythm and flow of the phrase, significantly damaging its impact. Sentences that violate parallelism disturb the reader like an off-key note disturbs a listener; both jolt and distract. The smooth flow of meaning is stopped until the reader can remove the blockage.

Misplaced and Dangling Modifiers

Modifiers are words or phrases that describe, identify, and specify another part of a sentence. We have examined adjectives, adverbs, adjective clauses, and adverb clauses—how they are used, how they are punctuated. How they are located in a sentence is another major concern. As the term indicates, a Misplaced Modifier (mm) is one not correctly positioned in its sentence. These are often the cause of unintended humor-and lack of clear meaning!

I saw the sick skunk driving down the street.

He wore a red beret on his head, which was much too small.

The underlined modifying phrase/clauses are placed next to the wrong nouns. The sentences need to be revised to place them next to the nouns they do modify:

Driving down the street, I saw the sick skunk.

He wore a red beret, which was much too small, on his head.

Dangling Modifiers (dm), too, are often sources of humor and twisted meaning:

Although exhausted and demoralized, the coach kept insisting on another lap.

Hanging by one toe from the rope 300 feet above, the performance was the most exciting of the circus.

The underlined modifiers are problematic because they refer to a subject who is either absent from the sentence or whose identity is unclear. In the above, the track team is missing as is the high rope performer. Revision is required:

Although the track team was exhausted and demoralized, the coach insisted on another lap.

Hanging by one toe from the rope 300 feet above, the high rope expert gave the most exciting performance of the circus.

Here’s one in which the subject of the modifier is present but unclear:

With only a 3.0 GPA, Rutgers’s graduate school nonetheless accepted Sarah.

As it is, Rutgers has a 3.0 GPA requirement. Revision:

Sarah, with only a 3.0 GPA, was accepted by Rutgers.

Squinting Modifiers occur when a modifier is placed between two words, either one of which could be its anchor. This confuses:

We were certain at noon our trip was canceled.

Does the writer mean: At noon, we were certain our tip was canceled, or that our trip was canceled at noon?

Placement of adverbs: Only, just, merely

Proper placement of these adverbs can determine and alter the meaning of a sentence.

For instance, consider the different meanings of:

I eat only one dessert per day.

I only eat one dessert per day.

Again:

Only I can eat the ritual meal.

I can only eat the ritual meal.

I can eat only the ritual meal.

Finally:

I can see merely the shadows.

I can merely see the shadows.

PUNCTUATION, MECHANICS, AND USAGE

Basic Rules and Conventions, Major Errors

This section focuses on the most important and most frequently occurring punctuation and mechanics errors—most important because they have negative effects on the clarity of meaning. Some are repeats and because they are often difficult to identify, the repetition should help you learn to “see” them more readily.

Sentence Fragments (frag) A sentence fragment is a group of words wrongly punctuated as if it were a sentence. The group starts with a capital and it ends with a period, question mark, or exclamation point. But it is not a sentence because it lacks one or more of the three ingredients: subject + verb + expression of a complete thought.

Fragments confuse readers who expect a complete thought but who get a partial product causing them to try to “figure it out” Thus, fragments undermine the purpose of writing, clear communication, and they frustrate readers who do not want the burden of puzzle solving.

The most common configuration you will find is illustrated as follows (from a student paper):

After everyone takes their* (pn agr) share, I refuse to take treasure; instead, I offer it to my good friend, Gandalf. Which shows how good natured I am. frag

The underlined fragment (dependent clause) comes after a correct sentence. The fragment expresses a point that is related to the sentence, but it is a dependent clause. Note: dependent clauses are often the most difficult for students to identify because they meet two criteria of a sentence; they have a subject and a verb. They are not, however, complete thoughts.

Grammar Highlight: Reading out loud will frequently make the reader hear the incomplete thought. “When I get home” Hearing that voiced will make the listener say, “When you get home, what?” Encourage students who habitually write fragments to read aloud—not under their breath!

Run-on (fused) Sentences (run) and Comma Splices (cs)

Like the fragment, these errors violate the rules of sentence structure. In this case, it’s about connections and misconnections. A railroad analogy helps explain this common error. Imagine that sentences are railroad cars. Now, like them, sentences or separate cars can be linked together—or coupled; they don’t have to be separate. Often to get an idea communicated most effectively, as to transport materials across the country, linking is the most effective method. But how?

To begin with, there must be a link. Just as you can’t expect to connect by placing two cars next to one another without a coupling mechanism, so, too, the writer cannot simply place two sentences (independent clauses) together without a link, as in:

The evening showers were soft and warm they made the night enchanting.

Dublin, king of his breed, strutted as he patrolled his yard his posture blared his dominance through every street and alleyway.

The underlining identifies where two independent clauses have been fused, or run on, without a coupler. Note: in the second example of a run-on sentence, there are two possible independent clauses.

Grammar Highlight: a run-on sentence is not about length; rather it’s about structure. A run-on lacks the coupler (FANBOYS, or semi-colon) necessary to link independent clauses.

Comma splice is the second type of fused sentence. Again, it’s a problem of connection. You can’t link two railroad cars with rubber bands; they are not strong enough. You can’t link two independent clauses with a comma—it’s not strong enough to do the job of communicating clearly.

The evening showers were soft and warm, they made the night enchanting.

Dublin, king of his breed, strutted as he patrolled his yard, his posture blared his dominance through every street and alleyway. cs

ONLY the FANBOYS or the semi-colon can do the communication job:

The evening showers were soft and warm, and they made the night enchanting.

Dublin, king of his breed, strutted as he patrolled his yard; his posture blared his dominance through every street and alleyway.

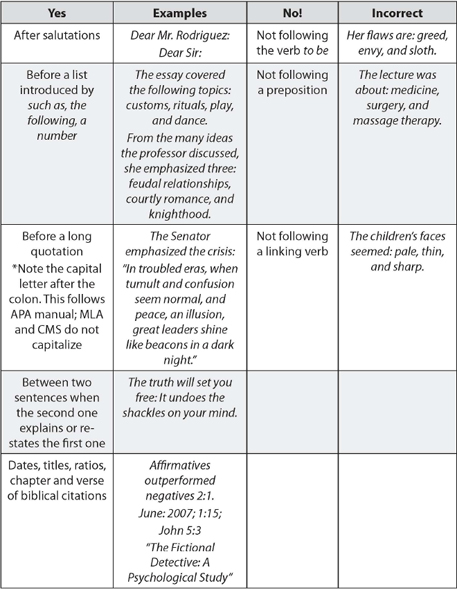

Semi-colons are confusing to many students. Yet their correct usage is straightforward and very limited. There are three grammatical situations which require them.

Requirements for a Semi-colon

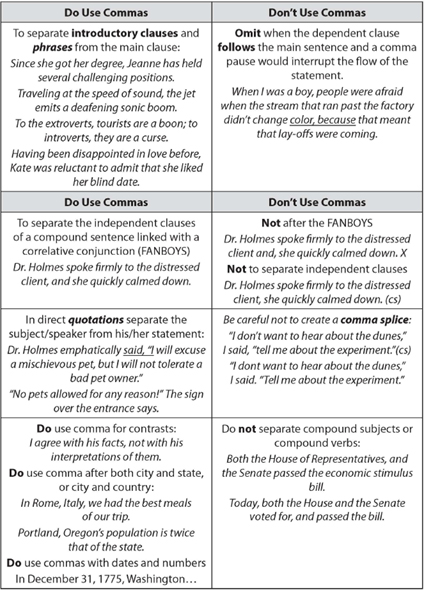

Commas

I have spent most of the day putting in a comma and the rest of the day taking it out.

Oscar Wilde

Wilde’s wry observation about comma choice highlights two important points: First, and this guides you in editing your and others’ writing, that placing commas where they don’t belong is a bigger problem with students’ writing than failing to use them where they do belong; two, that while we do have rules to guide these decisions, it is often not clear-cut when a comma is necessary.

The uses and misuses of commas are probably the single most troubling punctuation question. Perhaps this is because there are so many situations that require them and also so many situations in which they are incorrectly used. The correct use of commas is crucial to communicating meaning and also to the coherence of writing. Readers are ornery; they don’t like to be confused; they do like the sensation of smooth, flowing writing—that’s what coherent writing produces.

One guiding principle for all comma use is your best tool. That principle simply is that commas help the reader keep the various parts of a sentence in their proper places. Consider, for instance:

After leaving his friend John made his way to his mother’s apartment.

When you read the above sentence, you probably experienced a moment of confusion because your brain connected friend to John, which is not the meaning of the sentence. Rather:

After leaving his friend, John made his way to his mother’s apartment.

Here, the comma helps the reader; it “tells” the reader, “pause to meet John, who is the person who left his unnamed friend.” As for writing that is incoherent, consider this:

Since Alice hadn’t cooked the family decided to dine out.

To which the reader does a double-take: did Alice cook the family? After a confusing moment, the reader may succeed in getting it right—but not without some annoyance. The correctly placed comma avoids the confusion:

Since Alice hadn’t cooked, the family decided to dine out.

Now let’s look at a different comma problem. Consider: John took a walk, and talked with Mary about their engagement. This illustrates a frequently made error: placing a comma to separate a compound verb. The comma both breaks the flow of the verb action, putting a brake on the forward movement of walk and talk, and it confuses the meaning, suggesting that walking and talking are being compared, or that they happened at a different time. It’s important to foster this understanding with students.

Pronouns: Case, Agreement, and Reference

These frequent problems involve the all-important connection between a pronoun and the word to which it refers—its antecedent. As we have previously discussed, confusion in this relationship will obstruct meaning. Pronoun agreement is a very frequent error!

Agreement (agr): Does the pronoun match (agree) the number (singular/plural), gender (male/female), and person (1st, 2nd, 3rd) of its antecedent?

Examples:

Athletes frequently suffer injuries to their bodies.

Athletes, the antecedent is plural in number, neutral in gender, and in the third person. Their is plural in number, neutral in gender, and in the third person.

A reader must focus his/her attention sharply in order to see the miniscule marks in the margins.

A reader, the antecedent, is singular in number, either male or female, and in the third person. So, too, are his and her.

To be inclusive, whenever an antecedent can be either male or female, you need to use both his and her (so as not to exclude either the female or the male). However, too many of these constructions in a piece of writing make for awkwardness. To avoid these gender constructions often requires creating different sentence formats. For instance, changing the antecedent to plural removes the awkwardness because the plural doesn’t have different gender form.

Readers must focus their attention sharply in order to see the miniscule marks in the margins.

Agreement Challenges: Once the basic “mirror relationship” is understood, it seems easy to follow the agreement rule. However, there are several words and grammar constructions which cause difficulties.

Collective nouns—that is, nouns that refer to more than one person such as team, jury, committee, army. Note these words are singular in form; they therefore require a singular pronoun as in this example:

The committee left the boardroom and announced its decision to the court.

Sometimes, however, a writer does mean to describe the separate members of a collective and in this case, since the reference is to more than one, then the pronoun should be plural.

The committee left the boardroom and went to their offices to cast their votes for the proposal.

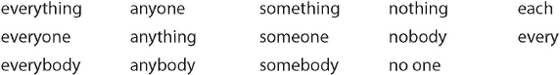

Personal pronouns called indefinites because they don’t specify gender or number take the singular.

Everyone is responsible for his/her belongings and must take precautions to secure them.

Anybody can apply by submitting his/her qualifications and years of experience.

Each student has his/her own computer.

Every book must be returned with its cover.

Commonly used Indefinite Pronouns

Faulty or unclear pronoun reference (ref)

Consider the pronouns in the sentence:

Jane hit the ball so hard that she sent it flying twenty feet over the fence.

We understand this because we clearly understand that the antecedent of she is Jane and that the antecedent of it is ball. This clear relationship is sometimes ambiguous or incorrect.

Claudia threw the vase at the window and broke it.

It is ambiguous; is it the window or the vase that was broken?

The Andersons told the next door neighbors that their children were chasing the chickens.

(Whose children—the neighbors’ or the Andersons’?)

Pronoun Case (case)

Subjective case is for pronouns functioning as subjects.

Examples: |

She purchased every bottle the store had. (subjective, singular) |

We purchased every bottle the store had. (subjective, plural) |

Objective case is for pronouns functioning as objects.

Examples: |

They called him from the pay phone. (objective, singular) |

They called us from the pay phone. (objective, plural) |

Possessive case is for pronouns functioning to indicate “belonging to.”

Examples: |

Gloria Gaynor sang her disco hits. (possessive, singular) |

The Bee Gees sang their hits from Saturday Night Fever. (possessive, plural) |

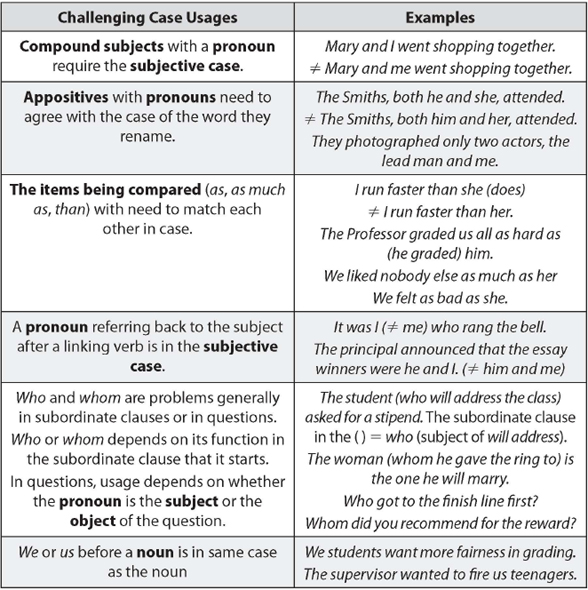

Pronoun Case

When you struggle to decide between using I and me, or who and whom, you are grappling with pronoun case. The right answer is in the rules above. However, two situations can make pronoun case difficult. One is because we often violate these rules in speech, so much so that the correct use sounds unnatural or pedantic as in “Whom did he call?” Yet, this is correct because whom is the object of the verb call. Second, there are several grammatical formats that cause confusion and make it tricky to determine whether the case we need is the subjective or the objective. Knowing these confusing formats helps us identify the most common problems people have with pronoun case.

Common Problems with Pronoun Case

Forming plurals

Most nouns can be singular or plural. The usual plural form adds -s to the end of the word.

desk desks |

book books |

However, there are exceptions to this guideline. After a -y preceded by a consonant, the -y changes to -i and -es is added.

sky skies |

secretary secretaries |

If the final -y is preceded by a vowel, no change is made, and the plural is formed by adding -s.

decoy decoys |

attorney attorneys |

If the last sound in the word is a sibilant—a word ending in -s, -z, -ch, -sh, or -x, or -z—add -es.

churches, sashes, masses, foxes, quizzes (however, with words ending in the sound of -z, it must be doubled before adding the -es)

class classes

However, if the -ch is pronounced -k, only -s is added.

stomach stomachs

Often the final -fe or -f in one-syllable words becomes -ves.

half |

halves |

|

wife |

wives |

There are exceptions, of course.

chief |

chiefs |

|

roof |

roofs |

Many nouns have plural forms that are irregular or the same.

For nouns ending in o, it depends on the word whether you add -s or -es to form the plural. These spellings must be memorized individually.

potato potatoes |

hero, heroes |

Finally, there are a number of foreign words that have become part of the language and retain their foreign plural form. There is a trend to anglicize the spelling of some of these plural forms by adding -s to the singular noun. In the list that follows, the letter(s) in parentheses indicate the second acceptable spelling as listed by Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary.

datum |

data |

|

medium |

media |

|

crisis |

crises |

|

parenthesis |

parentheses |

|

criterion |

criteria |

|

phenomenon |

phenomena (s) |

As you can see, there are many peculiarities associated with plural formation. Keep a dictionary on hand to check plural forms.

Possessive nouns (those that own something, or to which something belongs) use apostrophe plus an s (s’) as in,

Eleanor Roosevelt’s husband was perhaps the most famous president of the twentieth century; or,

The classroom’s ceiling is too high to be energy efficient; or,

Charles Manson’s behavior has become synonymous with modern psychosocial disorder.

If the noun showing possession is plural, and it ends as most plurals do, with an -s (boys, girls, and engineers), then only an apostrophe is used:

The engineers’ computers are left on even during the evening when they are not around.

The girls’ attitudes made them a delight to work with.

However, there are nouns that do not use an -s to form their plural. These non -s ending plurals—such as children, men, women—use an apostrophe and an -s to show possession:

The women’s hats are all different colors.

The children’s playground is across the street.

Joint Possession: In situations where two nouns “possess” something together, add the s apostrophe (s’) to the last noun owner:

John and Mary’s Mercedes Benz is frequently borrowed by their son for dates.

Be careful, however, if the subject nouns “own” separate and different things, then each requires an ’s:

Although they are married, John’s and Mary’s bank accounts are in different banks.

Possessive Pronouns do not use any form of apostrophe s. They are possessive in themselves and require no special sign:

The tree cast its shadow across the field. (Not it’s, which means it is; not its’: It’s not a word!)

Singular and Plural Possessives

Special Uses of Apostrophes

With plural words that end in s, add the apostrophe to show possession:

All of the boats’ lights shone in the harbor. (the lights of all the boats)

When showing the plural of individual letters of the alphabet, add an apostrophe s.

John could write his as perfectly clearly but he had difficulty with his b’s.

Note how the omission of the apostrophe in the lowercase plural for the letter a would confuse the reader (is it as?).

Contractions use an apostrophe to show that letters have been omitted, frequently in auxiliary verb constructions such as does + not = don’t, have + not = haven’t, and the one often misused as a possessive, it + is = it’s.

Faulty Predication (fp) occurs when the subject (the ‘who’ or “what” of the verb) doesn’t fit with the predicate:

Writing is where I have my greatest problems. (The subject writing is not a place (where)).

Horses are the activity she most relishes. (The subject horses is not an activity)

Revision:

I have my greatest problems with writing. Or, writing is my greatest problem.

In the second example, note that “my greatest” uses subjective case because it is the complement of a linking verb (to be).

Revision: Horseback riding is the activity she most relishes.

Quotations and Quotation Marks

Quotation marks are necessary with direct quotes, which are words that someone else exactly said or words exactly as they are written or spoken from a source such as a book or film.

Mary gave me very precise directions. “Do not,” she urged, “enter the kitchen, and do not open the door to the basement.”

According to the philosopher, Hannah Arendt, “Evil is banality.”

Indirect quotes are reports on what someone said, summarizing or paraphrasing it. They do not take quotation marks.

Sarah said that yesterday had been the worst of her life.

The historian Barbara Tuchman claimed that World War I was an unnecessary mistake.

Note: the word that is generally a sign that you are dealing with an indirect quotation. To indicate someone’s exact words, not the writer’s, requires quotation marks as when a character in a short story makes a statement:

John turned to Mary and confessed, “I quit my job.”

In essays, however, most quotations are to acknowledge another writer’s words on the subject of the essay; and in an argumentative/persuasive essay, we often use quotations as evidence to support our arguments.

Quotation Mechanics and Punctuation

Where and when to capitalize, to place quotation marks and punctuation marks such as period, question marks, and exclamation points is largely dependent upon the position of the quotation.

If it is at the beginning, the quotation starts with a capital, and ends with a comma inside the quotation marks. The same is true for question marks and exclamation points.

“I have loved you since we were children,” Mary admitted to John.

“Did you really love me all along?” John asked. “Yes!” Mary exclaimed.

If it is at the end of the sentence, place a comma after the source of the quotation, a capital letter for the first word, and the terminal punctuation if a period, question mark, or exclamation point inside the quotation marks.

Wendell Phillips says, “The Tree of Liberty requires constant pruning to maintain vital and true.”

The broken quotation is a bit more complicated. Let’s examine the varieties:

“The unexamined life,” says Socrates, “is not worth living.”

Note: The beginning follows the same format as noted above. The second part, which is a continuation of the first, is not capitalized, needs a comma after the source, and follows the same rules for placing the period inside the quotation marks. If, however, the quotation consists of two sentences with its source in the middle, note the changes:

“The unexamined life is not worth living,” says Socrates. “It is the life of the beast, not of the man.”

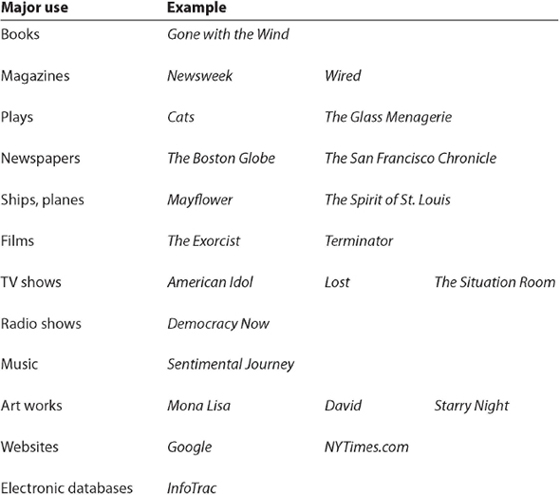

Quotation marks for titles

Colons and semi-colons go outside of the quotation marks:

The document stressed the accident’s “special circumstances”: It insisted that the holiday atmosphere changed normal behavior.

The killer coldly confessed that he “felt nothing at all”; then, he leaned back in his chair and yawned.

Grammar Highlight: Commas, periods, question marks and exclamation points are inside the quotation marks; colons and semi-colons are outside of them.

However, there are some tricky situations: Sometimes a quotation is not itself a question or an exclamation, but it’s part of a larger sentence that is a question or exclamation. In these cases, the question mark and exclamation point go outside the quotation marks.

Does Mr. Babbitt think he is alone in thinking that new courthouse is “a monument to injustice more than a temple of justice”? (It’s not Mr. Babbitt’s question.)

Samson didn’t have to go so far as to call the defendant “disreputable, heartless scoundrel”! (It’s not Samson who is outraged at these words.)

Embedded Quotations: When quotations are part of the larger sentence, note that there are no commas:

I pointed out to Jason that his belief that “all abuse cases should be treated the same” would lead to an abuse in justice.

The Judge concluded that the defendant is “a total psychopath incapable of redemption”; no doubt, his sentence will be harsh and invoke the maximum penalty the law permits.

Ellipses are used to indicate that material has been omitted from a quotation:

The author stated that his work “is meant to entertain, to instruct…but not to preach.”

If the omitted material comes in between two sentences in a quotation, add a period:

The author stated that his work “is meant to entertain, to instruct, to promote good values.…”

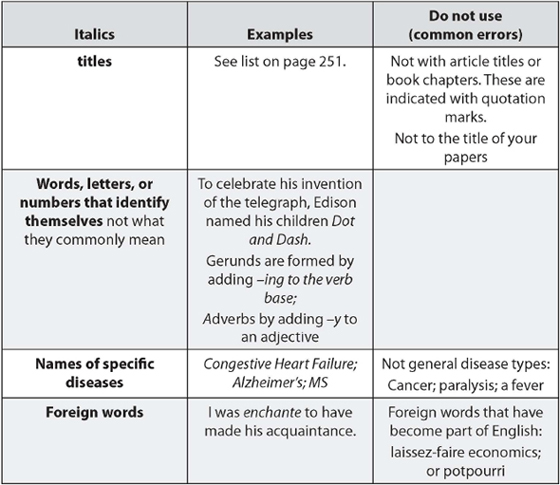

Word processing has made font styling easier and thus italics have replaced underlining in many instances.

CAPITALIZATION

A very important element of writing is knowing when to capitalize a word and when to leave it alone. When a word is capitalized, it calls attention to itself. This attention should be for a good reason. There are standard uses for capital letters. In general, capitalize (1) all proper nouns, (2) the first word of a sentence, and (3) the first word of a direct quotation. The following lists outline specific guidelines for capitalization.

Capitalize the names of ships, aircraft, spacecraft, and trains:

Apollo 13

Boeing 767

DC-10

HMS Bounty

Mariner 4

Sputnik II

Capitalize the names of divine beings:

God

Allah

Buddha

Holy Ghost

Jehovah

Jupiter

Shiva

Venus

Capitalize the geological periods:

Cenozoic era

Neolithic age

Ice Age

late Pleistocene times

Capitalize the names of astronomical bodies:

Big Dipper

Halley’s comet

the Milky Way

North Star

Ursa Major

Capitalize personifications:

Reliable Nature brought her promised Spring.

Bring on Melancholy in his sad might.

She believed that Love was the answer to all her problems.

Capitalize historical periods:

Age of Louis XIV

Christian Era

the Great Depression

the Middle Ages

Reign of Terror

the Renaissance

Roaring Twenties

World War I

Capitalize the names of organizations, associations, and institutions:

Common Market

Franklin Glen High School

Girl Scouts

Harvard University

Kiwanis Club

League of Women Voters

Library of Congress

New York Philharmonic

North Atlantic Treaty Organization

Smithsonian Institution

Unitarian Church

Capitalize government and judicial groups:

Arkansas Supreme Court

British Parliament

Committee on Foreign Affairs

Department of State

Georgetown City Council

Peace Corps

U.S. Census Bureau

U.S. Court of Appeals

U.S. House of Representatives

U.S. Senate

A general term that accompanies a specific name is capitalized only if it follows the specific name. If it stands alone, comes before the specific name, or is used on second reference, it is lowercased:

Central Park, the park

Golden Gate Bridge, the bridge

the Mississippi River, the river

Monroe Doctrine, the doctrine of expansion

President Obama, the president of the United States

Pope Benedict XVI, the pope

Queen Elizabeth I, the queen of England

Senator Dixon, the senator from Illinois

Treaty of Versailles, the treaty

Tropic of Capricorn, the tropics

Webster’s Dictionary, the dictionary

Washington State, the state of Washington

Capitalize the first word of a sentence:

Our car would not start.

When will you leave? I need to know right away.

Never!

Let me in! Please!

When a sentence appears within a sentence, start it with a capital letter:

We had only one concern, “When would we eat?”

My sister said, “I’ll find the Monopoly game.”

He answered, “We can only stay a few minutes.”

The most important words of titles are capitalized. Those words not capitalized are conjunctions (and, or, but) and short prepositions (of, on, by, for). The first and last word of a title must always be capitalized:

A Man for All Seasons

Crime and Punishment

Of Mice and Men

Rise of the West

Strange Life of Ivan Osokin

Sonata in G Minor

“Let Me In”

“Ode to Billy Joe”

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

All in the Family

Capitalize newspaper and magazine names:

The New York Times

the Washington Post

National Geographic

U.S. News & World Report

Capitalize radio and TV network abbreviations or station call letters:

ABC

CNN

HBO

NBC

WBOP

WNEW

Capitalize regions:

the Northeast, the South, the West

Eastern Europe

but: the south of France, the east side of town

Capitalize specific military units:

the U.S. Army, but: the army, the German navy, the British air force

the Seventh Fleet

the First Infantry Division

Capitalize political organizations, and in some cases, their philosophies, and members:

Democratic Party, the Communist Party

Marxist

Whigs

Federalist (in U.S. history contexts)

But do not capitalize systems of government or individual adherents to a philosophy:

democracy, communism

fascist, agnostic

Do not capitalize compass directions or seasons:

north, south, east, west

spring, summer, winter, autumn

Capitalize specific diseases:

Alzheimer’s

Swine Flu

DON’T capitalize general diseases:

cancer

flu

heart disease

Capitalize search engines, names of computer programs, internet service providers, websites, electronic databases:

Yahoo

Microsoft Word

America Online

HotWired

LexisNexis

InfoTrak

When to spell out a number and when to use the numeral (ten, or 10)—that’s the question! Unfortunately, there’s no simple answer because the experts differ: some say spell out numbers between one and ten, and use numerals for all above ten: Only 59 students out of 100 passed the test. Some experts, however, recommend spelling out all the numbers from one to ninety-nine. So chose whichever you like best, but be consistent.

There are some clear cut guidelines however. Never begin a sentence with a number—it must be spelled out:

CORRECT: |

Fifty-nine out of 100 students passed the test. |

INCORRECT: |

20 students flunked the exam. |

Do not spell, rather use numbers for any requiring more than two words:

CORRECT: |

We sent out 157 invitations. |

INCORRECT: |

We sent out one hundred fifty-seven invitations. |

If two numbers are next to one another, spell out one and use a number for the other:

CORRECT: |

John ran three, 50 yard races. |

INCORRECT: |

John ran 3,50 yard races. |

Percentages, statistics, distances, money are not spelled out, unless they begin a sentence!

CORRECT: |

Recycling removes 25% of waste from landfills. |

INCORRECT |

25% of the population recycles. |

CORRECT: |

Twenty-five percent of the population recycles. |

CORRECT: |

We drove 10 miles out of the way to find a Starbucks. |

CORRECT: |

The sweater cost $59.99. |

Commonly Misused Words and Phrases

Note that many of the confusions involve parts of speech.

A lot/a lot: a lot is informally used a lot. But it is incorrect.

“A lot” is a much used informal phrase; do not use it in your writing.

Advice/advise: advice is a noun; advise, a verb.

I never asked for your advice.

The counselor advised me to research the biotechnology field.

Affect/effect: affect is a verb meaning “to influence, or have impact upon”; effect is a noun meaning results of; effect can also be used to mean influence, or impact but not as a verb: The effects of nuclear radiation are radiation sickness, soil contamination, and global pollution.

Poverty affects the incidence of animal neglect. When people are short on cash, they sometimes abandon their pets.

My paper concerns the effects of television violence on children’s behavior.

All ready/already: all ready means fully prepared; already is an adverb meaning previously or before.

I was all ready to leave for my trip when I got the surprise cancellation.

By the time I arrived home, the family had already eaten.

Bad/badly: bad is an adjective and thus modifies nouns and pronouns; badly is an adverb.

John looked bad after his accident

John was badly hurt in the accident.

Breath/breathe: Breath is a noun; breathe is a verb.

I was all out of breath by the time I reached the summit.

She was so frightened that she couldn’t breathe.

Capitol/capital: A capitol is a building wherein a legislative body meets. A capital is either a political center as in, Boston is the capital of Massachusetts, or it refers to the uppercase letter that must begin all sentences. Capital can also mean goods, assets, cash.

Madoff bilked many investors of their capital.

Complement/compliment: complement means to go along with, to match; compliment means “to flatter.” Both can be either nouns or verbs.

The professor complimented the class on its stellar performance.

As one of the class members, I felt honored by his compliment.

Conscience: the part of mind that experiences right and wrong

After lying to his girlfriend, Jim’s conscience bothered him.

Conscientious: an adjective meaning very careful, attentive to requirements

He is a very conscientious teacher; lectures are always well-prepared.

Conscious: an adjective meaning aware or deliberate

Irena is often not conscious of how alienating her behavior can be.

Continual/continuous: continuous refers to something that never stops; continual to something that happens frequently but not always.

The continuous force of evolution means that change is inevitable.

Rainfall is the result of the continuous cycle of evaporation and condensation linking the waters of the earth and the clouds of its atmosphere.

The college students in the apartment above us have frequent parties that continually disturb us in the middle of the night.

Council/counsel: council is a noun and signifies a group; counsel is either a noun or a verb meaning advice or to advise

Four magnificent mutts, Dublin, Logan, Molly, and Sasha elected me to the Council of All Beings.

The council debated heatedly before finally deciding to whom the prize was awarded.

The therapist counseled my best friend to leave her relationship.

When I met her partner, I gave her the same counsel.

Desert/dessert: desert is an arid land; dessert is a delicious sweet food.

Arizona contains many deserts.

Dessert is the best part of the meal.

Mnemonics: As a desert lacks water, so the word lacks an s.

Every day/everyday: every day is a phrase, two words meaning “happening daily”; everyday, one word, meaning ordinary, usual

Every day I go to the gym to work out.

Arguments at dinner are everyday affairs.

Farther/further: farther refers to physical distance, while further refers to difference in degree or time

The restaurant is about two miles farther down this road.

His shifting eyes were further proof of guilt.

Good/well: good is an adjective; well is an adverb. Hence,

I may look good, but I don’t feel well.

He cooks very well.

Hanged/hung: unless you are referring to stringing someone up by a rope, use hung.

The stockings were hung on the chimney. The clothes hung on the line.

The vigilantes hanged John Dooley for his thievery.

Its/it’s: its is a possessive form of it—a pronoun; it’s a contraction of it is.

Our town must improve its roads.

It’s time to leave the zoo.

Like/as: like is a preposition; as is a conjunction that introduces a clause. Hence, if a statement has a verb, use as; if not, use like.

Dorothy drank as heartily as a thirsty camel.

Her muscles were strong and ropey like a weight lifter’s.

Loose/lose: loose means “not attached,” the opposite of tight; lose means to misplace

He has been accused of having loose lips: don’t trust him!

If I lose these keys, I’ll be in serious trouble.

Passed/past: passed is the past tense of the verb, to pass, meaning to move by, or succeed; past is a noun meaning before the present time

We passed two hitchhikers on Route 22.

In times past, people enjoyed much richer social lives.

Principal/principle: principal means a supervisor or something of major importance; principle refers to a value, an idea.

The principal of Sunnyside High was fired for fiscal irresponsibility. Some pal!

The fired principal was evidently not a man of high principles.

Proceed, proceeds, precede: proceed is a verb meaning to carry on, to go forth; proceeds, a plural noun, meaning revenue raised; precede is a verb, meaning to be ahead or in front of, or earlier than:

“Proceed, counselor,” bellowed the judge, “or be fined for stalling.”

In the Easter procession, the Bishops, priests, and other clergy precede the parishioners.

The proceeds from the raffle are going to the Food Bank.

Quote/quotation: quote is a verb; quotation is a noun

I chose a quotation from Karl Marx to summarize the negative effects of capitalism upon family ties.

I quoted Karl Marx to emphasize the adverse effects of capitalism on family ties.

Raise/rise: raise means to elevate, or to increase. Past tense is regular, raised; rise means to stand up, to get up. Past tense is irregular rose.

The State Department of Education is charged with raising academic standards.

The reform effort has successfully raised student achievement.

“All rise for the benediction,” the minister directed.

The congregation rose for the benediction as surely as the sun rises every day.

Real/really: real is an adjective; really, an adverb.

He is a real artist, in my opinion, contrary to the hacks employed in advertising.

He is a really good artist, despite his large commercial appeal.

Set/sit: set means to put down or to adjust; its past tense is also set. Sit is a verb meaning to place oneself in a sitting position; the past is sat.

John set his hat on the bureau.

After setting his hat on the bureau, John sat in his favorite chair.

Than/then: than is a comparison word; then is an adverb referring to time

The politics of health care are more complicated even than those of public education.

I got up at 8:00 AM and, then, five minutes later, I was on my way to the office.

Their/they’re: their is a possessive pronoun; there’re is a contraction for they are.

The Smiths can be annoying; they’re always late for dinner.

Their habitual lateness annoys their friends.

Used to/use to: used to is the past tense phrase to express a former action/state; use to is simply incorrect.

When American artists migrated to France in the 1920s, they used to gather at the Café Metro in Paris.

Who/whom: who is the nominative case; whom, the objective case (Review pronoun section)