CHAPTER 1 Background to Aboriginal/non-Aboriginal interactions in Australia

After working through this chapter you should have an understanding of:

To this end, the chapter is divided into two sections: Part A, Colonisation in Australia, and Part B, Government policies.

PART A: COLONISATION IN AUSTRALIA

Introduction

This chapter provides a broad overview of the history of colonisation in Australia and its aftermath. It sets out the background to the interaction between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in Australian society today and a chronological guide to government policies. It is essential that we begin here in order to explore why Australian history developed the way it did and why, even today, Australian society finds it difficult to deal with its roots. We need to remember too that this history has influenced, and continues to influence, all Australians—Indigenous and non-Indigenous, and that it has left us with a legacy of far-reaching social and emotional dis-ease.1 To understand the history of Aboriginal/non-Aboriginal interaction in Australia, we need some tools, such as an understanding of culture and culture change.

What is culture?

Hunt and Colander (1984, pp 43–4) provide a neat summary of the many and varied definitions of culture, by pointing out that culture includes the totality of a group’s behaviours, values and beliefs, as well as its art, language, tools, world view, symbols, in fact ‘a blue print for all human behaviour’ which one generation teaches the next.

Similarly other writers, such as Matsumoto and Juang (2004), believe that culture is a dynamic concept which identifies systems of rules, beliefs, attitudes, values and behaviours, shared by a group, taught across generations, relatively stable but capable of change across time. Schein (2004, p 17) focuses on the role of culture in problem solving and states:

The culture of a group can … be defined as a pattern of shared basic assumptions that was learned by a group as it solves its problems of external adaptation and internal integration, that has worked well enough to be considered valid and, therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems.

As Schaller and Crandall (2004) point out, if you asked a hundred people what culture is, you would get a hundred different answers. Therefore, ‘cultures must not be assumed to be uniformly shared among some aggregate of people. Everyone does not know the same things …’ (Irvine 2002, p 9).

However, most writers would agree that the dynamic nature of culture is not only influenced by the individuals who are members of the cultural group, but is also subject to environmental influences. We will take this approach in our analysis of colonisation in Australia.

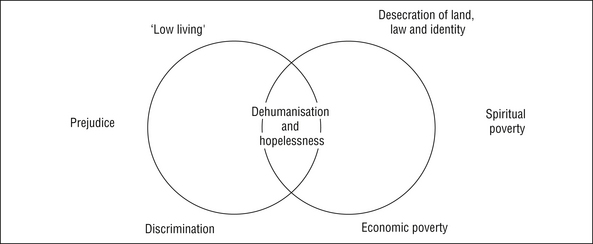

Our definition of culture is based on an ecological approach, which helps us to understand how environments influence cultural change and adaptation. Let’s start with the fact that all cultures are learned. Such learning takes place throughout life—people gain an understanding of the world and, in the first instance, learn values, beliefs and traditions from their families. Obviously these values, beliefs and traditions don’t exist in a vacuum; they are influenced by the class and ethnic group to which people belong. They are an essential part of the styles of living that guide action. They influence how people think, act, interact, are motivated and make decisions. Overarching these cultural values are the environments in which they are enacted. By ‘environments’ we mean more than the physical environment—how people think and act is very much influenced by the economic, political, social and historical environments in which they and their group(s) interact and have lived. This is a key to understanding culture and how it changes—that is, to accept that human beings, their social groups and their social, economic, political, historical and physical environments, are inseparably linked. The interaction of culture, environments and individuals is presented diagrammatically in Figure 1.1. Note that there is a feedback loop, which suggests that we respond to, initiate and adapt to change in our environments and vice versa.

Figure 1.1 The interrelationship of culture and environment

(Eckermann 1994, p 28; adapted from Ramirez & Castaneda 1974, p 60)

Such an approach to ‘culture’ is not without its critics. Some Aboriginal people maintain that the cornerstones of their culture are lore, law, language and land, which form the basis of their identity.

Culture, for us, then, is more than ‘a people’s way of life’. Culture tells us what is pretty and what is ugly, what is right and what is wrong. Culture influences our preferred way of thinking, behaving and making decisions. Most importantly, culture is living, breathing, changing—it is never static. Because of this, it is important to understand the forces that lead to change and adaptation.

Adaptation

The process of adaptation is important. It is based on problem solving, steeped in creativity, and characterises the process of coping when environments—physical, economic, political, historical and social—change. Because the process is dynamic, because it is influenced by perceptions, needs or perceived needs, wants and wishes, it is not easy or smooth. As Sahlins (1968, p 369) pointed out many years ago:

To adapt … is not to do perfectly from some objective standpoint: it is to do as well as possible under the circumstances, which may not turn out very well at all.

If we consider colonisation in Australia within this framework, we begin to see some of the forces at work.

Over the past 40,000-plus years, Aboriginal people clearly adapted to their environments in Australia. This adaptation proved wholly satisfactory and the people developed unique social, cultural, religious and economic ways of life.

In 1788 Australia was ‘discovered’—or should we say invaded and colonised—by Europeans. They too had developed unique social, cultural, religious and economic ways of life based on centuries of adaptation in Europe. But adaptation in the two societies had taken different forms and, alien and inexplicable to one another, the two met head on.

Culture clash, culture conflict and culture shock resulted. Ultimately, the ‘pushier’ culture, with greater numbers and more deadly weapons, won out—Australia was colonised by the European invaders.

Let us briefly step aside and consider what these terms mean.

DEFINITIONS

DEFINITIONS

CULTURE CLASH

McConnochie (1973) points out that two important factors will determine whether or not cultures clash: whether or not people recognise each other as human beings, and whether or not people share, or believe they share, similar values and beliefs. So, when people from different cultures ‘look alike’ and seem to ‘be alike’, culture clash is less likely to occur than when people from different cultures ‘look different’ and seem to ‘be different’. Human beings find it difficult to tolerate difference; they are generally suspicious of ‘strangers’ and apt to react to such strangers on the basis of ethnocentrism and stereotypes, or over-generalisations. Our own group, or Us, becomes the in-group; and strangers, or Them, become the out-group.

Let us spend a little time sorting out concepts such as ethnocentrism, stereotypes, prejudices and discrimination.

ETHNOCENTRISM

We found Matsumoto and Juang’s (2004, p 63) definition of ethnocentrism useful. They define:

… ethnocentrism as the tendency to view the world through one’s own cultural filters … it follows that just about everyone in the world is ethnocentric. That is, everyone learns a certain way of behaving, and in doing so learns a certain way of perceiving and interpreting the behavior of others. This way of perceiving and making interpretations of others is a normal consequence of growing up in a society. In this sense, ethnocentrism per se is neither bad nor good; it merely reflects the state of affairs—that we all have our cultural filters on when we perceive others.

The problem is that the ‘other’ becomes less good, or dangerous, or strange. ‘They’ become ‘the other’ to ‘Us’. A stranger in a small town is ‘other’, a person from another country is foreigner or ‘other’, a poor person is the ‘other’ to the privileged and vice versa. ‘Otherness’ may also be assigned to a whole range of human characteristics – gender and sexual orientation, religion or spiritual belief, ethnic origin or migrant experience, age or generation, and disability.

STEREOTYPES

Stereotypes are overgeneralisations (see Allport 1982). They, too, are part of human life and thinking because people are encouraged from an early age to categorise the things around them. For example, we categorise an object as ‘table’—whether it has four legs or one leg makes no difference. Consequently, overgeneralisations always deprive the ‘object’ of individuality. As a result, when stereotypes are applied to people, we develop ‘mindsets’ (whether these are positive or negative) which deny individual talents and abilities, e.g. all southern Europeans are hot blooded.

PREJUDICES OR PREJUDGeMENTS

These are the positive or negative attitudes people develop around the stereotypes they have about the ‘other’. Prejudices are based on half-truths, myths, rumours and overgeneralisations in which we invest a good deal of our emotions. As a result, prejudices become quite resistant to change. Prejudices in their turn can lead to discrimination.

DISCRIMINATION

Discrimination is the acting out of prejudice, the active speaking or acting against those who are different from ‘us’. But discrimination can also take the form of providing or not providing a service to an individual or family because we assume we ‘know’ what’s best for them. So discrimination can take the form of acts of commission as well as omission.

CULTURE CONFLICT

Cultures in conflict find it difficult to understand each other and consequently difficult to adapt to one another. If people do not share language, similar lifestyles and expectations, are not committed to similar goals and motivated by mutually understandable ambitions, do not make decisions on the basis of similar principles and philosophies, then culture conflict will occur. When one cultural group has power over another it may impose its systems and organisations, even to the extent of enforcing its beliefs and values on the less powerful group by violence or legislative sanctions.

CULTURE SHOCK

Any individual who has ever travelled, lived or worked with another cultural group has experienced some measure of culture shock. It is that feeling of uneasiness, anxiety and stress that arises when suddenly all our familiar cues, language, interpersonal relationships, tastes and actions appear to be out of place, suspect or even inappropriate, and we must reassess our behaviour in the light of foreign expectations.

When culture clash and culture conflict involve groups with unequal power, the less powerful, as individuals and as a group, experience the anxiety associated with culture shock. Subordinate status ensures that its members lose control over the process of adaptation, and their reality becomes defined by the oppressor.

Our framework for analysing the colonisation of Australia needs to incorporate the processes of culture clash and the inevitable ramifications of culture conflict and culture shock. It can do this if we remember two things.

Aboriginal people, like Europeans, have always had to adapt to other groups sharing their environments. In both cases they shared with groups fairly similar to themselves. Although there were many different Aboriginal cultures and languages in Australia BC (‘Before Cook’, as Oodgeroo2 used to say), Aboriginal nations shared some fundamental principles (see Berndt & Berndt 1988): a spiritual association with their land; a social commitment to kin; and a religious affiliation with the Dreaming from which they derived their values, norms and social–emotional and spiritual wellbeing. The economy was based on hunting and gathering, and although they have been described as ‘nomadic’, they actually followed a very structured/seasonal migration within their territory to make use of the resources it provided. Extremely sophisticated kinship structures and rules governed interpersonal behaviour, marriage and trade, while extraordinarily rich forms of art, dance and music enhanced their lives. Equally importantly, contact, and at times conflict, between nations was governed by strict rules of engagement and never led to land alienation.

When the colonists arrived, Aboriginal societies suddenly had to accommodate a group with a very different world view, economy and social structure. European society, on the other hand, did not have to adapt to traditional Aboriginal Australia; it simply took over. Consequently, the onus fell on the traditional owners, the subjugated, to ‘fit in’, to find a new niche in their own country. This niche was, and still is, largely defined by the more powerful non-Aboriginal majority.

Terra nullius

The process of colonisation began with the ‘discovery’ of Australia by Captain Cook, who claimed the land for the Crown as ‘uninhabited’. The classification of Australia as ‘terra nullius’—an empty continent—was based on extreme ethnocentrism combined with scientific racism, incorporated into the British and European legal codes. Australia was named ‘empty’ because Aboriginal people ‘failed’, in the invaders’ eyes, to use the land, to display those features then assumed to be the mark of ‘civilisation’—use of agriculture, settlement in towns or cities, government by chiefs, kings and/or parliaments. The invaders’ perception of ‘civilisation’ and ‘settlement/occupancy’ were clearly guided by political philosophers of the time. Thus de Vattel (1758) wrote that:

Of all the arts, tillage or agriculture is without doubt the most necessary and most useful. It is the chief source from which the state is nourished, cultivation of the soil increases greatly its produce, it constitutes the surest resource and the most substantial find of wealth and commerce …

… it is the justification, of the rights of ‘Property’ and ‘Ownership’ …

… when, therefore a nation finds a country uninhabited and without an owner, it may lawfully take possession of it …

… when the Nations of Europe, which are too confined at home, come upon lands which the savages have no special need of and are making no present and continuous use of, they may lawfully take possession of and establish colonies in them.

(de Vattel 1758, quoted in Wright B 1986 Aboriginal/Settler Relations)

Such concepts were also enshrined in the writings of the English economist Locke, who argued that land ownership was dependent on working the land. Land that was not cultivated was consequently empty, common land that could be taken by those who would cultivate it—other lands, annexed through colonisation, could be held by the Crown to be sold or leased to those who wanted to cultivate it later (Miller 1985).

As a result, two principles governed all future Aboriginal/non-Aboriginal interactions. The first was that Australia was considered an empty continent; the country was discovered, annexed and settled—Aboriginal people were not even accorded the status of ‘conquered people’ (Gumbert 1984). Consequently, the British government did not feel obliged to negotiate a treaty, unlike any other European colonial situation since the 1600s. The second was that, when Cook ‘claimed’ Australia, the whole of the continent became Crown Land. Both principles proved to have far-reaching consequences for the position of Aboriginal people in the country AC (After Cook).

Consider

Before we go on, stop for a minute and consider:

After reading about the basis on which Australia was declared ‘empty’, what does that tell you about Europeans’ perceptions and evaluations of different cultures?

They had no understanding of, but felt they had a right to evaluate, to measure, other cultures against their own. (We will pursue this theme and its roots later.) Importantly, this ‘habit’, established in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, persists—we continue to evaluate ‘others’ in terms of our own frame of reference. It is a common yet destructive habit, and shows little understanding of the intricacies and complexities of the term ‘culture’.

The process of colonisation in Australia was unique only because of the annexation of Australia as an ‘unoccupied continent’. In all other aspects, colonisation in Australia followed the patterns established in all other parts of the world. We will discuss how these were manifested in Australia next.

Cultural relativism

All cultures are learned and shared products of how groups come to terms with their environments, their needs, wants, aspirations, hopes and fears. A people’s culture is satisfying, appropriate and proper for them—others may follow different traditions, emphasise different values, because they have different needs and wants. Consequently, while a culture is right and proper for those who follow its traditions, it may not be appropriate for others, better than others’, or the only way to conceptualise the world. Those who wish to work with culturally different groups must therefore support a position of cultural relativism—that is, an acceptance that different cultures represent the legitimate adaptation of different peoples to various historical, natural, socio-economic and political environments. This does not mean that we should abandon our own traditions or philosophies. It does mean that we suspend judgement about those things that we do not understand, that we make a conscious effort to become sceptical of rash evaluation of what is ‘good’ and ‘bad’ for others, and that we constantly question our own predisposition to seek security in those things that we feel we ‘know’ about other groups. Fundamental to this process is identifying the cultural groups to which we belong—societies are not homogeneous; they are composed of many groups, which adhere to differing values and beliefs. What are our values and beliefs?

Principles underlying colonisation in Australia

The four keystones of colonialism in Australia, as anywhere else in the world since the eighteenth century, include:

We will apply these to the Australian situation as some of the variables that have influenced Aboriginal/non-Aboriginal interactions, which form the historical past on which our present is based.

Basic ethnocentrism and xenophobia

Previously we have argued that all groups are ethnocentric to some extent.

Unfortunately ethnocentrism may lead to xenophobia—a morbid fear of foreigners or, indeed, anything perceived as strange and different.

When Cook first visited Australia he believed that the Aboriginal people he saw were far happier than people in Europe because they did not have or indeed seem to want the trappings of European civilisation. Instead, he noted that ‘[t]hey live in a Tranquillity which is not disturbed by the Inequality of Condition … ’ (Cook, in Beaglehole 1955, p 399).

This now famous quotation from his journal reflects Cook’s philosophy of the ‘Noble Savage’, which, arising out of the Enlightenment, reflected ‘a sympathy and respect for primitivism which extended from the classical writers to the more recent accounts of the North American Indians’ (Williams 1985, p 43). While these descriptions of Aboriginal people appear favourable, they are nevertheless ethnocentric in that the ‘primitive’, the ‘Noble Savage’, is described as living in a utopian, elementary state of development. The stereotypes of tranquillity, simplicity and equality, however, do not persist for long.

As colonialism spread, the imagery reverted back to Dampier’s famous description of Aboriginal people as ‘the miserablest People in the World’ (cited in Williams 1985, p 35). By 1846, they were thought to be at the lowest rung of evolution, without civilisation, clothing, knowledge of housing or agriculture, eager to eat grubs, snakes and carrion (Woolmington 1973, p 16).

Similar statements were made by all sections of colonial society—see the works of Evans et al 1988, Lippmann 1999, Reynolds 1989 and Moses 2004 for excellent examples. Summarising the writings of the mid-1870s, Moses (2004, pp 5–6) points out that Aboriginal people were described as:

‘ineradicably savage’ … the male possessed the deportment ‘of a sapient monkey imitating the gait and manner of a do-nothing white dandy’ as well as suffering from a ‘low physiognomy’ that rendered him lazy and useless. ‘It is their fate to be abolished; and they are already vanishing’, … The ‘aboriginal Australian blacks … were so extraordinarily backward a race as to help them to hold their own’.

Obviously, perceptions of Aboriginal people had changed drastically since the image of the Noble Savage found in the journals of Cook and others. Why? Perhaps because colonisation and culture contact had brought home the realities of culture clash and culture conflict, of power and powerlessness, as well as the need to rationalise land alienation and exploitation.

This kind of ethnocentrism was not only extended to Aboriginal people. Consider the xenophobia inherent in the Boomerang’s (1891) editorials. (The Boomerang was a Queensland daily newspaper.) For example, the paper urged all good Queenslanders not to give way to the influences of Italians (considered to be at a lower level of human development) and their evil, cheap labour (see Evans et al 1988).

Similar material was published about the Chinese by newspapers, clergymen and so-called ‘scientists’. These writers maintained that:

[The Chinese] physiognomy indicates no beam of intelligence or play of fancy but rather stolid stoicism … They have been described as ‘materialism put in action’ being sceptical and indifferent to everything that concerns the moral side of man and destitute of religious feelings and belief …

Colonial society, then, was intolerant of all ‘others’, including many poor European immigrants, and convicts. From these short quotes it is obvious, however, that although ethnocentrism and xenophobia devalued those who were not ‘white’ Anglo-Saxon, the imagery varied between different groups. Italians and Chinese were clearly considered a real economic threat. Aboriginal people, on the other hand, were of such a ‘low species’ that they were believed to belong to the lowest rung of humanity.

Partly this kind of reasoning arose from and was supported by the scientific ‘research’ of the time.

‘Scientific’/intellectual climate

As long as people have lived in groups and met strangers who looked different from them, they speculated about the reasons for such differences in appearances. The ancient Greeks hypothesised that differences in appearance were due to climatic variations. During the 1700s theorising about such differences began to be couched in full-scale ‘scientific’ speculation about the nature of humanness. In line with physical scientists, philosophers and social scientists attempted to account for progress, development and cultural differences. At the same time, theologians as well as scientists attempted to explain evolution and change. Hundreds of research papers were published by Europeans speculating about the physical, cultural and spiritual qualities of non-Europeans.

This search reached fever pitch in the mid-1800s through the impact of Social Darwinism, a bastardisation of Darwin’s theory of evolution applied to physical, cultural and intellectual evolution. As writers such as Miller (1985) and Reynolds (1989) explain, much of this research was based on the concept of The Great Chain of Being by which all life was arranged in a hierarchy, from the simplest to the most complex—that is, ‘man’. In turn, human beings were arranged in a similar hierarchy, from the most ‘primitive’ to the most ‘civilised’.

Such research has been termed scientific racism. As McConnochie et al (1988, p 14) point out, it is based on three premises:

Consequently we need to sort out what we mean by racism and scientific racism.

DEFINITIONS

DEFINITIONS

Like McConnochie et al (1988), Cashmore and Troyna (1983, p 35) maintain that racism is:

The doctrine that the world is divisible into categories based on physical differences [most important of which are/were skin colour] which can be transmitted genetically. Invariably, this leads to the conception that the categories are ordered hierarchically so that some elements of the world’s population are superior to others.

This doctrine developed from the ‘scientific’ research which set out to establish the superiority of ‘whites’ over all other skin colours, cultures, religions, family organisations, art, music and general ‘development’.

Scientific racism, then, is the research carried out by scientists into the physical, social, intellectual and moral qualities of culturally different people where such differences are equated with inherent, biological inferiority, when compared to qualities associated with the scientists’ own in-group. Most frequently this in-group has been Western European.

Such ‘scientific’ research became the basis of and justification for a number of stereotypes about Aboriginal people, which, we would argue, are still being perpetuated. Some of these stereotypes included the notion that Aboriginal people were locked into a static Stone Age culture and environment; that they reacted/survived by instinct rather than by use of intellect; that they were ancient, archaic survivors of the ‘missing link’; that they had only a rudimentary religion, history and government; and that, overall, they were childlike and consequently unpredictable. These stereotypes are fully explored in the work of Chase and von Sturmer (1973), McGrath (1995), Lippmann (1999), Broome (2002) and Moses (2004).

Scientific racism was reflected in the ‘non-scientific’ statements of the day. As Woolmington (1973, p 14) points out, as early as 1789, the Aboriginal nature was blamed for the fact that the early settlers had failed to implement Governor Phillip’s orders to ‘conciliate their affections’. Thus, John Harper, who was to investigate the possibilities for establishing a mission around Batemans Bay, wrote that the Aboriginal people in the area were ‘degraded … almost to the level of brutes … [and] in a state of moral unfitness’ (Woolmington 1973, p 18)

The attitudes and values, misconceptions and stereotypes formed about Aboriginal people at that time on the basis of ‘scientific thought’ still persist today and are still used to justify the position of Aboriginal people in our society.

Let’s have a brief look at a ‘travel journal’ written in 1889 by an ‘anthropologist’ called Carl Lumholtz. This book, entitled Among Cannibals, describes Lumholtz’s four years of travel in Queensland and his experiences among Aboriginal people in the west and north of that State. Lumholtz portrays Aboriginal people as the lowest of the human race (p 113), lazy (p 162), and as having no traditions or historical sense (p 223). He claims that even the most ‘civilised’ cannot be trusted (p 294), know no religion (p 366) and lack any faculty of artistic appreciation (p 367). This he considers is clearly linked to their small skulls and low intellectual development (p 282), their childlike tendencies (p 211) and their treachery (p 285). In short, Lumholtz’s book is a supreme example of the scientific racism that characterised the nineteenth century. Why do we hark back to that book here? Because it was republished in 1979, and its blurb claims that it is a valuable account of ‘all aspects of Aboriginal culture and Australian wildlife’.

Similarly, consider some of the comments made in the press in 1984 by highly respected leaders of our community when the Federal Government was considering introducing national land rights legislation. Below is an article that appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald

Extract

Land rights: a step back to paganism

By PAUL KELLY and PATRICK WALTERS in Canberra

Aboriginal land rights threaten to wipe out the Australian mining industry, represent a spiritualism that is anti-Christian and will create a bitter backlash from the wider community, according to the executive director of Western Mining Corporation, Mr Hugh Morgan.

In a speech yesterday to the Australian Mining Industry Council here, Mr Morgan launched the most far-ranging attack on the land rights concept by accusing the Federal Government of supporting Aboriginal sovereignty over land and setting aside all constitutional prerogatives to the contrary.

Referring to the land rights movement, he said that the mining industry was being attacked on religious grounds by an anti-Christian doctrine when its own Christian basis had been established in St Paul’s First Letter to the Corinthians.

‘For a Christian Aborigine, land rights or the proposed Heritage Protection Act is a symbolic step back to the world of paganism, superstition, fear and darkness,’ Mr Morgan said.

He drew the battle lines by warning that the mining industry spoke not just for itself but for many Australians of European, Aboriginal and Asian descent who would not go in the direction set by the Government.

‘The Australian people would be appalled if the consequences of Crown ownership of minerals for everybody else, but Aboriginal control and hence de facto ownership of minerals on Aboriginal land, were carefully and simply explained to them,’ he said.

‘If the doctrines and principles underlying the Northern Territory legislation are applied to the rest of the Commonwealth, then there will be no exploration activity in this country, and ultimately, no Australian mining industry.

‘We are entirely legitimate in complete obduracy when such fundamental issues are at stake,’ he said, adding that land rights was an area where compromise was impossible.

‘Either the Crown owns the minerals or it does not. If it does not then those who do own or control minerals have, in particular places, very great potential financial, even political advantages when compared with the rest of the Australian community.

‘Belonging to that particular group of people will become a major ambition for those not belonging.’

Aboriginality was now virtually ‘a matter of self-definition’. But, because such financial advantage was going to be bestowed upon people by virtue of descent, self-definition would become impossible and a register of Aborigines would be needed with all of the racial classifications that implied.

‘I do not think that either governments or commentators have realised the full implications of present policies,’ Mr Morgan said.

‘If these creeds are given legislative support, if the legislation uses these beliefs as justifying argument, then it will be very difficult to deny either legitimacy or financial support for the whole package of tribal belief, custom and practice.

‘On what grounds can a minister or a parliament say, on the one hand, we respect, recognise and give legal support to the spiritual claims you have to a very substantial portion of this country, but on the other hand we cannot sanction infanticide, cannibalism and the cruel initiation rites which you regard either as customary or as a matter of religious obligation …

‘It is relevant there to note that vengeance killing, a religious duty, exacted a far greater toll on the Aboriginal population in the nineteenth century than any depredations by the Europeans.

‘Charges of genocide of the Aborigines by our nineteenth century forebears, whether they be made by ministers or by land rights activists, are nonsense.’

Mr Morgan said that Aborigines exacted a fearful toll on each other—a greater toll in proportion of their number than the casualties sustained by the European armies at the battle of the Somme in 1916.

‘Nineteenth century accounts of clashes between Europeans and Aborigines, particularly in North Queensland, are quite explicit concerning the partiality of the Aborigines for the particular flavour of the Chinese, who were killed and eaten in large numbers.’

Defending the mining industry, Mr Morgan quoted St Paul saying, ‘Let every man abide in the same calling wherein he was called.’

He said that St Paul was a tent maker and knew in his own time that mining was a key factor in the prosperity and defence of the Roman Empire.

‘Those who attack us as materialist, unspiritual, are themselves heretical in their religious philosophy. They are followers of Manichean doctrines which have always been condemned by the Christian church as heresy.’

Mr Morgan likened some ministerial statements on land rights with Manichean doctrines—founded by a third century Arabian preacher, Mani.

He drew the contrast with Christianity as a ‘religion which celebrates work and the physical world which is universal’.

Land rights attack

Mr Morgan’s comments signal the industry’s determination to fight the Government’s proposed legislation on both sacred sites and land rights and they ensure that these issues will return to a very high place on the political agenda.

Questioning the basis of sacred sites, Mr Morgan asked whether orebodies were sacred sites. He said the mining industry was being made a scapegoat since the orebody was usually found before the sacred site was declared.

He quoted the lines spoken by Ben Blakeny when the Queen opened the Sydney Opera House more than 10 years ago, which began with: ‘I am Bennelong. Two Hundred years ago, fires burned on this point … the fires of my people.’

Mr Morgan asked whether anybody could deny with confidence that the Opera House site would not be claimed as a sacred site.

Speaking to the same conference, the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs, Mr Holding, said the campaign against land rights was being used by more extreme groups as part of a broader effort with racist overtones.

Note how illogically Morgan links land rights with paganism, and cannibalism and mining with Christianity and progress; how he denies and dismisses the true history of colonisation; and how cleverly he supports ignorance and fear of Aboriginal rights.

Activity

Look at the newspapers today, check out the web, and analyse the kinds of statements made about Aboriginal people. Are similar arguments perpetuated in the twenty-first century?

But let’s not get too far off the point. What message did ‘scientific’ material of this kind put across and how did it support official and unofficial policy towards Aboriginal people?

Certainly the all-pervading message of ‘inferiority’ made it easy to justify alienation of land and colonial exploitation of Aboriginal labour. Both land and labour were important to the colonisers and their commitment to ‘progress’ and ‘development’ born out of the period of industrialisation that dominated Europe in the nineteenth century.

The Protestant ethic and industrialisation

Again we need to recognise that extremely far-reaching changes in European value structure, economic and social organisation, and political structure made it almost impossible for Australia not to become a colonial possession.

From the mid-1700s and throughout the 1800s, Europe moved through enormous social, cultural and economic change. Societies that had a mainly rural economic and social base, governed by hereditary rulers, controlled by orthodox religion, became urban-based nation States reliant on industry, governed by parliaments and influenced by belief systems, which questioned orthodox dogma. Changing values stressed the importance of achievement, of materialism and wealth as indicators of God’s grace, where once piety, resignation to fate and acceptance of the established order had ruled the day. No longer was it a sin to reach beyond one’s station in life—progress, development and achievement were defined materialistically and the more one had (individually as well as nationally), the better one was. These rapidly changing States of Europe required resources in order to feed their nationalistic and industrial fervour. No continent escaped their militaristic and economic expansion.

Broome (2002) maintains that Aboriginal resistance to this new order was frequently interpreted as ‘laziness’ by those committed to the value of work as an expression of piety, and quotes a Moreton Bay missionary who described Aboriginal people as follows:

Among these evil dispossessions of the Aborigines I may mention an extreme sloth and laziness in everything, a habit of fickleness and double dealing … They are deceitful and cunning and prone to lying. They are given to extreme gluttony and if possible will sleep both day and night.

Christie (1979) presents an interesting analysis of how these forces influenced the pattern of invasion in Australia. In Christie’s account, the struggle for land, the ‘scientific’ rationale to support such theft, and the cruelty of this time, all interact. He concentrates his analysis on Victoria and shows that:

It was the ‘best way’, wrote Black, ‘provided the conscience of the party was sufficiently seared to enable him to, without remorse, slaughter natives right and left’.

Similarly, Stevens (1981), Yarwood and Knowling (1982), Lippmann (1999) and Broome (2002) point out that ‘scientific’ rationale, negative attitudes towards ‘primitives’ and religious arrogance were not the only factors underlying Australian colonisation. An equally strong motive was economic exploitation, particularly land/labour exploitation. Indeed, in his analysis of Aboriginal labour relations, Stevens (1981) demonstrates that the tie between ‘scientific’ rationale and economics created Aboriginal living conditions, which were akin to slavery.

This early contact set the framework for the present position of Aboriginal groups in Australian society. Resultant poverty, the vicious circle of dysfunctional adaptation and the miserably constrained ecological niche prescribed for Aboriginal groups by the dominant non-Aboriginal system sets the scene for what Galtung (1990) calls cultural violence.

Cultural violence

European cultures were/are exemplified by a ‘hard’ religion (Galtung 1994)—one that demands complete commitment and is relatively intolerant of other belief systems. Their ideology was and continues to be shaped by the Protestant ethic and its emphasis on achievement and wealth, which continues to shape Australian society. Thus as late as 2006, Hugh Morgan believed that Australia, like the great city states of Northern Italy, should celebrate wealth and linked this value to the parables in the Bible.

I would like to see the word ‘rich’ recover its respectability. Margaret Thatcher once gave a sermon on the parable of the Good Samaritan in which she emphasised that the hero of the story was a businessman who was rich enough to pay for the hotel costs of the traveller (rescued by the Good Samaritan) who had been beaten and left for dead.

Similarly, European sciences have been instrumental in raising racism to respectability by ‘proving’ that non-whites were inferior on the human ladder of development and evolution.

The process of colonisation certainly demonstrates the level of direct violence to which Aboriginal people were subjected—so far we have identified forcible dispossession supported by racist language, science and ideology. As a consequence, European culture(s) ‘preaches, teaches, admonishes, eggs on, and dulls us into seeing exploitation and/or repression as normal and natural, or into not seeing them (particularly exploitation) at all’ (Galtung 1990, p 295).

Galtung’s analysis becomes very real when we look at the process of colonisation in Australia in more detail.

The process of colonisation

The colonial ‘push’ took different forms in different States and occurred at different times—approaches towards the ‘Natives’ varied, but never the end result, which was dispossession. Such dispossession was firmly based on a belief in absolute superiority, and legal as well as philosophical justification which argued that:

given the Divine injunction to subdue the earth, the Indian [or Native] could not expect to remain forever in exclusive possession of the whole … continent.

As a result, Australia’s history is characterised by a long struggle for land, marked by up to thirty years of guerrilla warfare, massacres, retaliatory raids and open genocide.

To clarify the process of colonisation, we will follow Bodley (1975) and consider colonisation in terms of the uncontrolled frontier, establishment of government control, development of government control, and the aftermath of contact.

The uncontrolled frontier

We all know that Australia was fully occupied BC (Before Cook). We also know that Captain Cook ‘discovered’ the continent and took possession of it. Colonisation spread fairly rapidly after the turn of the nineteenth century, across New South Wales at least. Still, until the 1850s, Australia could be described as a ‘frontier’ situation in which British law was supposed to cover all subjects of the Queen (Aboriginal as well as non-Aboriginal people) but in which the law did not actually reach much beyond the major settlements. In some areas, such as Queensland, Western Australia and the Northern Territory, the frontier days lasted well into the 1900s.

This time was marked by local guerrilla warfare between settlers and Aboriginal people as well as by some accommodation between the two groups. A steady increase in the numbers of settlers, the areas ‘opened up’, and improved communications also led to the rapid dehumanisation of those Aboriginal groups closest to places of major British settlement.

Some historians talk about the influence of convicts and sheep (Yarwood & Knowling 1982, for example) and this is a good way of conceptualising some of the factors in Australia’s colonisation. However, we would maintain that the loss of the American colonies played a much greater part in ‘opening up’ Australia than a need to find a ‘home’ for British convicts. Perhaps the fact that Aboriginal groups first came into contact with the most dehumanised sections of European society—the convicts—did influence later contacts.

Thus Ward (1982), in his book Australia Since the Coming of Man, presents a vivid and enlightening picture of Australian colonial society, its general lawlessness (the activities of the Rum Corps, for example) and its brutality (floggings, hangings, systematic sexual exploitation of convict women):

A more wicked, abandoned, and irreligious set of people have never been brought together in any part of the world … order and morality is not the wish of the inhabitants; it interferes with the private view and pursuits of individuals of various descriptions.

Yet Ward’s analysis, as well as that of most other historians, suggests that the real damage was done by ‘civilised’, arrogant, racist, free settlers rather than the convict element. This makes sense, particularly in view of the fact that the ‘real problems’ were related to land alienation and value conflict.

McConnochie’s (1973) model clarifies this. As we have pointed out, McConnochie maintains that the two most important factors that determine how negative colonialism/culture clash will be are: whether or not groups recognise each other as human beings, and whether or not groups share similar values. Yarwood and Knowling (1982) demonstrate that value consensus at initial contact was low—individualism, ‘achievement’, personal gain, ‘improvement’, ‘work’, values based on the Protestant ethic, found little reflection in the value structure of traditional Australia. Further, there was no ‘religious’ consensus. Europeans brought with them a ‘hard religion’ (Galtung 1994) that was intolerant of other philosophies, maintained rigid rules of right and wrong tied closely to the Protestant ethic, and functioned within hierarchies of established power and class. It seems to us that the people most likely to exhibit such values and also most likely to be in positions of power over Aboriginal people were not convicts, but squatters, farmers and traders (apart from the police, government officials and ministers of various religious groups). Ward (1982) suggests that the ‘squattocracy’ in Australia was drawn from the English middle class rather than the upper class. Perhaps it proved more ‘open’ in its exploitation than the ‘upper’ class because it was not steeped in the same tradition of ‘sensitivity’ or ‘humanism’. These were the people who took on ‘the white man’s burden’—that is, to uplift the poor savages, or to drive them off land that the settlers wanted, or to exploit their labour where possible.

Inevitably, then, the level of conflict between the traditional owners, who had suddenly become ‘reduced to “want land” ’ (Reynolds 2003a, p 23), and the colonists was high. The literature is full of references to the ferocity with which small Aboriginal groups defended their country. Broome (2002) records many battles, such as those along the Darling River, which kept pastoralists and stock away, or the fierce Aboriginal campaign for the east coast of Van Diemen’s Land; or, for example:

In South Australia the Milmenrura people of the Coorong region carried out an effective resistance in the early 1840s. They raided stations and settlements, often in groups of 300 warriors, firing pastures, dispersing and destroying stock. Several detachments of the military had to be sent against them. Similar fighting raged in the south Queensland region in the 1840s.

Similarly the contributors to Perkins and Langton’s (2008) First Australians, recorded Aboriginal freedom fighters in every state.

There is, then, no doubt that Aboriginal warfare played havoc with non-Aboriginal settlement. For example, in the Condamine, ‘[s]everal stations had been abandoned, twelve white men murdered, and a considerable number of cattle and sheep lost’ (Skinner 1975, p 31). Similarly, Reynolds (1987, p 9) points out that ferocious warfare was carried out over extended periods of time and that from 1830, right through to the 1880s, farm workers and squatters in New South Wales, Queensland and South Australia were in constant dread of being attacked and killed.

Many writers, including Skinner (1975), Broome (2002) and Kinnane (2008) further argue that such guerrilla warfare did not cease until the formation and deployment of the Native Police, which was composed of Aboriginal troopers recruited from distant areas, commanded by white officers. Their job was to re-establish confidence among the settlers and, to that end, they ruthlessly pursued any group of Aboriginal people in the vicinity of any disturbance. Thus in the Fitzroy Region of Western Australia there:

… was one of the most horrific incidences of mass murder in the history of this state … it was a ruthless campaign designed to inflict mass fatalities; men, women and children …

The numbers actually killed during such raids or massacres throughout Australia ‘no one but their commander and themselves ever knew’ (Skinner 1975, p 31). Broome (2002) adds that the war between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people was fairly evenly pitched, until, in addition to the Native Police, the introduction of the repeater rifle and Aboriginal decimation by disease took their toll.

Even today, the ‘frontier times’ are remembered and form a part of the people’s present folklore. Mrs Quinlan from Armidale, for example, recounts in her life story:

that was the time of the killing … They were killing all through the area. The worst was a fella called — … Suppose he had a lot of others to help as well. I lost one grandmother over the bluffs near Armidale. They killed a lot of our people—pushing them over the bluffs—Wollomombi, you know. Then the other grandmother, I lost on the Macleay on Pee Dee Creek. They used to herd them up and shoot them—go about shooting blacks like wallaby I suppose. They were only young women …

Establishment of government control

After the period 1830–50 in south-eastern Australia, and much later in northern and western parts of the continent, settlement density and the extent of agricultural/herding exploitation increased. As Lippmann (1999) and McGrath (1995), among others, have pointed out, government agents such as police, magistrates and the Native Police took over the task of keeping law and order. Early government policy of extending to Aboriginal people the privileges of British citizenship had been largely forgotten. The law now considered them wards of the State, unable to testify before the courts because they were not Christians. Further, neither the upholders of the law nor the general public showed much respect for or patience with Aboriginal people. Aboriginal people, they maintained, had given ample evidence of their treachery, laziness, mental inferiority and general barbarity. Therefore, in any conflict between Aboriginal people and Europeans, the law tended to favour Europeans.

Indeed, it seems that fewer Aboriginal people died through actual conflict of arms than because of the destruction of their livelihood (alienation of their land), undermining of their social organisation (dispersal of groups, capture of Aboriginal women, addiction to alcohol), and disintegration of their religious world view (activity of missionaries).

Mulvaney (1975) provides some excellent insights into the ecological upheavals caused by changes in land use due to non-Aboriginal settlement. He points out that:

To judge from numerous recollections of early European settlers, the advent of stock and unsystematic burning had drastic ecological effects … Pastoral occupation upset the delicate balance of nature through over-grazing and the destruction of grasslands and forest which provided many edible seeds and roots and supported a rich fauna; erosion also followed. In Western Victoria, brush and useless timber grew thickly in areas of former open woodlands; even in 1900 it was possible to gallop a horse near Aboriginal art sites in the Grampian Mountains where today the brush is almost impassable; Major Mitchell recorded the same impression for the Sydney area a century earlier … In arid areas, where erosion was so marked, another factor operated. After a few good seasons grazing on slowly regenerating native grasses, stock fouled and trampled shallow waterholes, and by destroying the surrounding vegetation, ensured their elimination through evaporation and erosion …

Such ecological changes caused havoc with Aboriginal food supplies. Further land alienation disrupted the social/spiritual structure of groups. Woolmington’s (1973) analysis of archival records indicates the influence of alcohol, prostitution and disease on the fragmented groups, which sought some form of livelihood on the outskirts of non-Aboriginal settlement. The work of Evans et al (1988) records equally depressing facts. These authors demonstrate how, through the process of colonisation, Aboriginal people’s social, economic, political and physical environment changed rapidly and drastically, while their participation in the new environment(s) was strictly defined and constrained by the dominant white society. As a result their new social, economic, natural and political environments became predominantly negative.

Consider

A whole people became the victims of social, economic and cultural trauma, and as a subordinate group they became subject to the colonisers’ definitions of themselves.

This pattern finds clear reflection in Aboriginal people’s legal status in colonial society. Little (1973), one of the first to explore the legal status of Aboriginal people, maintains that they were never really admitted to the status of British subjects—despite the fact that there were a number of concerned humanitarians who advocated for Aboriginal rights throughout the nineteenth century (see Reynolds 1989). Instead, at various times they were accorded features of such subordinate statuses as ‘conquered subjects’, ‘wards’, ‘hostile Aliens’, and ‘persons unworthy of legal protection’. Indeed, Little (1973) argues, Aboriginal people were most often confined to slave status—certainly throughout the nineteenth century. Reynolds (2000, pp 88–9) records that:

Many station owners—and other people who had Aboriginal servants—clearly believed that they owned rather than employed the blacks who worked for them. In 1885 a correspondent wrote to the Queenslander from Thargomindah describing the situation of Aboriginal servants in the south-west of the colony. They were employed in all the towns and on all the stations. Indeed it was hard to see how the stations could ‘be worked without their assistance’. They were ‘bound by no agreement’, but were talked about ‘as my, or our niggers, and [were] not free to depart when they like[d]’. It was not considered etiquette to employ blacks ‘belonging’ to another station and when ‘boys’ or ‘girls’ ran away they were pursued, taken back and flogged.

Why did non-Aboriginal society react like this? Hartwig (1973), Evans et al (1973), McConnochie (1973), Reynolds (1982, 1987) and Lippmann (1991), to mention just a few, demonstrate that colonial Australia needed to rationalise and justify its actions—that is, dispossession of land and exploitation of labour. In the process, Aboriginal people throughout Australia became subject to institutional racism

DEFINITION

DEFINITION

Institutional racism is manifest in the laws, norms and regulations that maintain dominance of one group over another. It is covert and relatively subtle; it originates in the operation of essential and respected forces in society and is consequently accepted. Because it originates within the society’s legal, political and economic system, is sanctioned by the power group in that society and at least tacitly accepted by the powerless, it receives very little public condemnation.

Why have these facts been ignored for so long? From a non-Aboriginal perspective, the kind of ‘scientific’ material produced by Lumholtz ([1889], 1979) and his contemporaries has helped non-Aboriginal Australians ignore Aboriginal people and their place and plight in Australian society. The history of dispossession has ensured that most non-Aborigines have shied away from clear analysis, while in the past the legal system has helped to subjugate Aboriginal people and to sanction their oppression. Equally importantly, historians, as Hartwig (1973) argues, displayed the same ‘mental block’ by consistently ignoring and minimising the place of Aboriginal people in history as well as the role of race relations in Australian society. Indeed it was not until the early 1970s that historians, such as Hartwig or Evans et al (1973), became seriously involved in the debate about Aboriginal issues and the reality of racism in Australian history.

It could be argued that such neglect bears all the marks of cultural violence—remember how many generations of Australian schoolchildren heard either nothing about Aboriginal people in their classes, or were presented only with the explorer Dampier’s comments that Aboriginal people are among the most brutal and primitive in the world. Hartwig (1973) also argued that such neglect reflected a cult of forgetfulness and disrespect.

Obviously, ‘forgetfulness’ and ‘disregard’ of Aboriginal people have been a feature of the Australian education and social, as well as legal and economic, systems for generations. Undoubtedly such ‘mental blocks’ have had their effect on our present attitudes and values. Indeed, reactivating the disregard and disrespect of past Australian histories, Windschuttle (2002) has argued that there were no atrocities associated with colonisation; that Aboriginal people never owned the country and that they were far too primitive to understand the concept of property ownership, to carry out warfare and to survive European settlement.

Activity

Return to Galtung’s (1990, p 291) definition of cultural violence:

By ‘cultural violence’ we mean those aspects of culture, the symbolic sphere of our existence—exemplified by our religion and ideology, language and art, empirical science and formal science … —that can be used to justify or legitimise direct or structural violence.

Now reflect on the establishment of government control in colonial Australia and list those aspects of cultural violence inherent in colonial society that have demonstrably disadvantaged Aboriginal people.

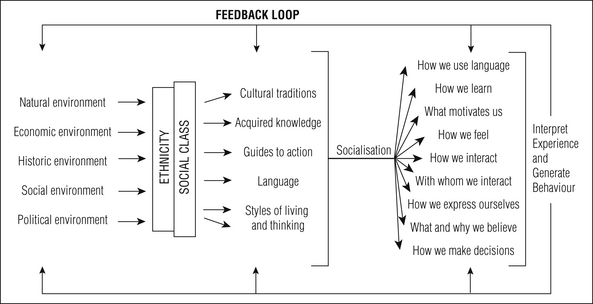

To understand these factors a little better, we will focus on Myrdal’s (1971) analysis of race relations.3 Myrdal argues that any interaction of minority and majority (or Indigenous and colonising cultures) is marked by the following aspects. Minority and majority act towards one another on the basis of distinct statuses. The inferior status of one (minority/Indigenous group), based on numerous factors (e.g. cognitive conflict, stereotyping, prejudice, history of contact), results in a standard of lower living and this ‘lower living’ reinforces inferior status. In this vicious circle, one state accommodates the other. The effect is cumulative. As one state occurs, other aspects of the circle are brought into play and these have repercussions on all other factors of interaction and adaptation. Change, Myrdal (1971) argues, frequently demands some readjustments, but these tend to reinforce the vicious circle rather than reverse its effects, particularly if the circle is maintained by institutional racism.

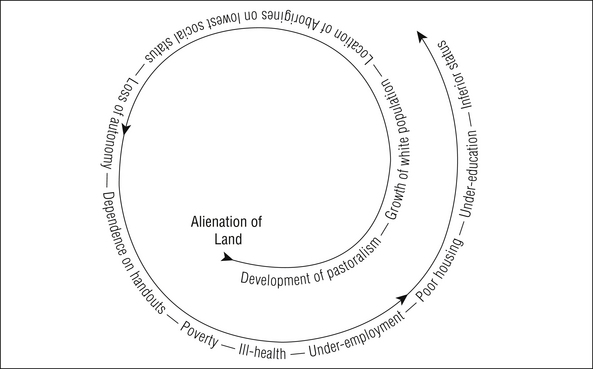

Consequently, in Australia, cultural, social and economic disruption led to ‘low living’ in Myrdal’s terms, which reinforced and supported disruption. In the process, two vicious circles were set up. One perpetuated Aboriginal poverty, the other consolidated negative attitudes towards the minority by means of the earned reputation theory. Diagrammatically we can represent this as two intertwining circles, as in Figure 1.2.

Thus, while scientific racism provided initial justification for discrimination on the basis of earned reputation (that is, Aboriginal people are so low on the human scale that they really are little better than animals and deserve to be treated as such), as contact intensified, dispossession and disruption also intensified, and observation of the latter provided further evidence of Aboriginal non-humanness and further justification for discrimination. This discrimination then became embodied in the law, regulations about where Aboriginal people could live, how long they could attend school, for how much they could sell their labour, and whether or not they were fit parents, capable adults and thinking decision makers. In this way, through the process of establishing government control in the colonial situation, racism became institutionalised—it was no longer an individually accepted phenomenon, but had become established within the system

Following Galtung (1990), it is clear that Australian culture became one of violence towards Aboriginal people. Think about the following descriptions of Aboriginal people as colonisation and government control spread, and more and more groups were dispossessed of their country:

George Carrington defined these ‘tame blacks’ as those who:

Hang about stations and public houses, and the outskirts of towns, begging always, stealing when they get the chance … They learn to drink grog and smoke and become weak and lazy, content to live on the white man’s scraps, rather than exert themselves to get their own living …

The stereotype of the derelict Aborigine which developed, therefore was built upon such observations as these …

Such stereotypes typified all Aboriginal people as:

a most idle thriftless lot … [who] will never settle to work with any regularity … They can never be made of much use to the settler … [They are] neither industrious nor trustworthy and will never become reliable servants …

Here is an excellent example of victim blaming. Aboriginal people are/were forced off their country, lost their independence, saw their social and religious institutions under attack from all sides, at times turned to ‘anti-social’ non-Aboriginal pastimes and were then blamed for the state of affairs in which they found themselves. Again consider Galtung’s (1990, p 295) words: ‘[it] dulls us into seeing exploitation and/or repression as normal and natural, or into not seeing them (particularly exploitation) at all’.

As a result of widespread colonisation, Indigenous people became completely demoralised—and with demoralisation came exposure to and death from European introduced diseases, which wiped out whole groups and totally undermined others. Between 1870 and 1890 the Indigenous population decreased to such an extent that ‘scientific’, popular and government opinion considered it inevitable that they would die out.

Consolidation of government control and aftermath of contact

Lancaster-Jones (1970) presents an excellent analysis of the decimation that took place. Consider his statistical analysis of the Aboriginal population between 1788 and 1966: the estimated Aboriginal population of 300,000 in 1788 had fallen by between 50 and 90 per cent by 1947, depending on geographic area … Even given the fact that—‘All figures except those of 1961 … involve considerable guesswork, are of uncertain reliability, and in some cases omit sections of the Aboriginal population’ (Lancaster-Jones 1970, p 5)—these are horrific statistics, particularly when we remember that Butlin (1983) estimates the population of Victoria and New South Wales alone to have comprised some 250,000 people BC, while Mulvaney (2002) has suggested that the Aboriginal population was about 750,000 at the time of first contact.

Lancaster-Jones’ (1970) and Rowse’s (2004) analyses indicate that by 1947 the population was once again on the ‘upsurge’, yet even then the estimated population sizes had recouped at most between 15 and 50 per cent of their original numbers. Different States reflect the decimation of colonial war and its aftermath at different times, depending on the years in which these processes occurred.

To salve public and private conscience, governments decided to protect Aboriginal people on reserves, where they could be housed and fed until their last remnants had disappeared. This was the beginning of the Protection Era, which Rowley (1978) calls the era of ‘Smoothing the dying pillow’. Numerous settlements, missions and reserves were set up—mainly on land which Europeans didn’t want—rations were handed out and the people’s lives were ordered and controlled by government or mission staff. A number of Acts were passed to ensure Aboriginal protection; they also ensured that Aboriginal people lost all vestiges of civil rights and became totally dependent on government/mission organisations.

Note that, although official policy changed from Protection/‘Smoothing the dying pillow’ to ‘Assimilation’ in the 1930s, missions and reserves were still being established until well into the 1940s. This period sees the expansion and solidification of institutional racism.

Before we analyse government policies in greater depth, let us summarise the materials we have discussed in relation to Aboriginal/European contact in Australia so far. Past cultural traditions and European attitudes, formed by the Industrial Revolution, basic ethnocentrism and the scientific traditions of the time, led to institutional racism and cultural violence, which characterised European reaction to Aboriginal people. A combination of basic racism and economic motivation led to the displacement of Aboriginal groups by means of force, the undermining of Aboriginal traditions through Christianity, the extermination of people by disease and war, the dislocation and dehumanisation of Aboriginal people through alcohol, disease, sexual abuse and economic exploitation. Diagrammatically we present this in Figure 1.3.

Activity

After working through the material on colonisation, it would be worth taking time to think about the following issues:

The land rights issue with which we battle today, which arouses such heated emotions—for as well as against—is with us now because hostilities between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people have never been settled, because the resentment of 100 years of institutional racism and resultant cultural violence have never been addressed on a national/political level or on a cultural level—that is, within an Australian cultural perspective, which recognises its roots, not only in Europe but also in traditional Australia.

To really understand current issues, we must be aware of the many policies and Acts that have shared Aboriginal/non-Aboriginal interactions. In Part B we will look at these in detail.

PART B: GOVERNMENT POLICIES

Every Act imposed on Aboriginal people between the 1890s and the 1960s can be classified as an example of institutional racism embedded in cultural violence. Let’s take each of the major policy eras in turn. Remember that from 1788 to the 1890s there were no overarching policies but rather piecemeal, missionary-inspired approaches within a general climate of neglect and ‘elimination’. This was followed by the segregation era, by assimilation, integration, self-determination, self-management, a decade of reconciliation as well as economic rationalism, and, now, after the Federal Government’s Apology to the Stolen Generations for past wrongs, the possibility of a new beginning. These eras are summarised in Table 1.1. Note that the dates indicated in the table relate largely to the eastern parts of Australia—some would argue that forcible assimilation still dominates Aboriginal communities in remote Australia. We have plotted government policy to the present, because we believe that Australia continues to be dominated by colonial attitudes and policies. It could be argued that the attitudes, beliefs and practices of colonisation were well and truly extinguished in the 1960s, but we do not agree. Aboriginal people are still subject to attitudes, beliefs and practices born out of the history of colonisation—and there is still no recognition of Aboriginal sovereignty.

Table 1.1 Interaction between the history of colonisation and legislation directed towards Aboriginal people

Each of these historical facts can be translated into actual or de facto policy eras, which have influenced and continue to affect Aboriginal communities.

Protection/segregation (1890s–1950s)

The first official, legally sanctioned policy was the Protection Policy. We have referred to it previously, but what did this policy mean to people’s lives?

Through ‘protection’ or ‘Smoothing the dying pillow’, as de Hoog and Sherwood (1979, p 29) point out, Aboriginal people were issued with rations, which were barely enough to survive, and the Chief Protector of Aborigines became the legal guardian of all Aboriginal and ‘part-Aboriginal’ children up to the age of 16, which gave him enormous power over these children’s lives—even the power to remove them from their parents. Further, reserves were set aside for Aboriginal people to live in segregated communities, Aboriginal children could not attend State schools, many country towns enforced curfews and they were not allowed to go to Perth. Aboriginal status was defined by an Act of Parliament, and anyone who wanted to escape the conditions imposed on Aboriginality had to gain exemption papers and refrain from associating with other Aboriginal people. ‘Protected’ Aboriginal people could not access social services payments, were not allowed to drink, vote or live with a non-Aboriginal person unless they had specific permission from the Chief Protector. Interestingly, as the Depression took hold, rationing was decreased which caused further pressures.

It is certainly true that de Hoog and Sherwood (1979) are referring specifically to Western Australia; however the conditions described applied fairly uniformly throughout the country. What struck us was that as the Depression hit, so ‘assimilation’ within ‘protection’ was adopted.

Assimilation within protection

Although assimilation became official policy during the 1950s, it had already been made explicit in 1939 when the then Minister of the Interior, John McEwan, said:

the final object of the Government in its concern for these native people should be the raising of their status so as to entitle them by right, and by qualification, to the ordinary rights of citizenship, and enable them and help them to share with us the opportunities that are available in their own native land.

Rogers (1973) believes that this policy had its roots in two distinct Australian traditions: the principle of equality of opportunity, and the egalitarian ethic. We don’t agree with Rogers and would urge you to remember the time when these sentiments were being expressed, as well as the actual actions that occurred. The times (the 1930s) were marked by widespread economic depression—the last thing on people’s minds was the welfare of the least-valued section of Australian society. The times were marked by political upheavals, particularly in Europe, which was still very dear to the heart of the Australian Government, at least.

The actions of State governments and their agents certainly belied any emphasis on equality of opportunity and the egalitarian ethic. Throughout the 1930s control and subjugation of Aboriginal people in fact intensified. This was the period when self-supporting, independent Aboriginal people were forcibly rounded up by police and placed on reserves under the pretext that ‘training’, in isolation, in segregation, was necessary before Aboriginal people could be admitted to citizenship and ‘equality of opportunity’.

the law in New South Wales allowed an Aboriginal or a person ‘apparently having an admixture of Aboriginal blood’ to be removed by order of a court to a reserve, where he must remain until the cancellation of the order … thus during the depression New South Wales authorities followed the hard practice of what was sometimes referred to in Western Australia as ‘clearing the towns’. This correspondence in time of economic disaster with harsh laws is suggestive of majority attitudes …

Not surprisingly, those people thus removed lost rights to unemployment benefits while, as de Hoog and Sherwood (1979) point out, rations on reserves were cut. Aboriginal people ‘found themselves in a very grim predicament’ indeed—unable to live off the reserves, yet economically dependent and living in poverty on the reserves. Governments, however, could save money while maintaining that they were concerned only with Aboriginal people’s welfare.

Some time ago, Anne-Katrin Eckermann recorded Mrs M Quinlan’s life story (1983). Her story clearly indicates that her people were dispossessed twice: once when the Dhunguddi were forced off their land during the time she calls ‘the killings’. The second time, when government policy, as described by Rowley, changed Bellbrook, her father’s farm, from an independent and self-sufficient Aboriginal settlement to a government institution. The parents and grandparents of many people currently living in north-western New South Wales had similar experiences at that time. They were forcibly removed by police from Tibooburra and placed on the nearest government settlement—Brewarrina, even though they lived and worked in self-supporting droving camps. This was the time of the NSW Aboriginal Protection Board, which had enormous powers over Aboriginal people in that State.

The Board, not the parents, was charged with the provision of custody, maintenance and education of children. It could appoint local (white) committees and (white) officers known as ‘guardians’ of Aborigines. It could remove any Aborigine from a reserve (regardless of the fact that his or her whole family were resident there) and could ‘apprentice’ a child to any occupation. Should the child refuse, he or she would be sent to an institution. Outside employment of adults could be terminated by the Board, which might require an employer to pay the wages of an Aborigine to one of its own officers …

Other States followed similar policies and supported similar boards or departments to enforce them. In Queensland, for example, complaints were made about Ena Chong’s father, whose number was W-163, because he and his friends were ‘cheeky’ and ‘seem to be under the impression that they can go about as they desire …’ (Office of Protector of Aboriginals North Queensland 1945) after which the Director of Native Affairs issued a memorandum that he:

… should be informed that if he continues to associate with aboriginals, i.e., allowing aboriginals controlled by the Act to reside with him in his house, he is making himself liable for the cancellation of his Certificate of Exemption issued to him in February, 1942.

Thus, assimilation as interpreted by McEwan, at times did little to ‘raise’ Aboriginal people’s status, instead it marked the continuance or imposition of protectionism.

Assimilation (1951–65)

In 1951, the Assimilation Policy became very clearly defined.

It stated that all Aborigines shall attain the same manner of living as other Australians, enjoying the same rights and privileges, accepting the same responsibilities, observing the same customs and being influenced by the same beliefs, hopes and loyalties.

One important aspect, deleted from later official policies, was McEwan’s (cited in Rogers 1973) reference to ‘their own native land’. Perhaps by the 1950s and 1960s the ‘threat’ of land rights was becoming real enough to ensure that no government would commit itself to acknowledging prior ownership officially. We would argue that this era in Aboriginal polity should be included within the framework of protection/segregation because, although policies may change, administrators generally do not. Although policies may be influenced by misguided but humanitarian principles, their implementation depends on attitudes and values that are influenced by a whole history of scientific/institutional racism and cultural violence. Thus, as Lippmann (1981) points out, the States continued the process of dehumanising Aboriginal people by means of special ordinances, such as the Welfare and the Wards’ Employment Ordinances 1953 of the Northern Territory, which made them wards of the State if their lifestyle was thought to be inappropriate, they were considered unable to manage their own affairs, they associated with ‘undesirables’, i.e. other Aboriginal people, and their behaviour was evaluated as unacceptable.

Consider

Consider the enormous amount of power that such an ordinance hands over to administrators.

Consider the dangers inherent in having your ‘personal associations’ classified and evaluated by someone who has the power to totally disenfranchise you. Consider this in relation to your own life.

By 1965 the Assimilation Policy was redefined to read:

The policy of assimilation seeks that all persons of Aboriginal descent will choose to attain a similar manner of living to that of other Australians and live as members of a single community—enjoying the same rights and privileges, accepting the same responsibilities and influenced by the same hopes and loyalties as other Australians.

(Commonwealth of Australia, Aboriginal Welfare Conference 1963)

However, even this element of choice, now introduced to the policy, did little to alleviate the cultural pressures exerted on Aboriginal groups to be ‘just like white Australians’. These were not social pressures, but legal pressures, enforced by a whole bureaucratic structure in each State and its agents.

These legal pressures made it possible for agencies to forcibly remove children from their families on spurious grounds. Even towards the end of the twentieth century, some eight per cent of Indigenous people in New South Wales ‘aged 25 years and over reported that they had been taken away from their natural families by a mission, the government, or welfare’ (ABS 1996, p 1).

The personal devastation caused by the policies of segregation/protection and assimilation are still being felt today and have been extensively documented by the report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families, 1997, Bringing Them Home. This publication caused enormous concern in Australian society, not only because it highlighted hundreds of heart-rending stories of abuse and neglect, but also because the reality of such abuses contradicted and challenged basic Australian values of social justice and human rights. It could be argued that, because this inquiry was open and public, many Australians had to face the fact that they had been so ‘dull[ed] … into seeing exploitation and or repression as normal and natural, or not seeing them (particularly not exploitation) at all’ (Galtung 1990, p 295) that they had become silent witnesses of cultural violence. Ten years after the release of the Report, comparisons of levels of dis-ease between those Aboriginal people who were removed from their families and those who were not, demonstrated that those who were removed experienced higher levels of long-term illness, poorer educational outcomes, higher rates of violence, higher rates of problems with the law and poorer rates of employment (MCATSIA 2006).

A change to self-determination or self-management? (1972–1988)

Since the mid-1960s, we have become familiar with policy statements advocating integration, self-determination and self-management. De Hoog and Sherwood (1979, pp 30–1) distinguish these three approaches in Aboriginal affairs as follows:

Integration puts an emphasis on positive relations between the Aboriginal and white community, while recognising that Aboriginal people may have different needs and aspirations in some aspects of their lives.

Self-determination takes these different needs and aspirations further, literally meaning that Aboriginal people should have the right to choose their own destiny, with government help in an enabling role, providing finance, technical skills, and social and economic support.

Self-management, which is the current Federal policy, has somewhat similar stated aims, but stresses that Aboriginal groups must be held accountable for their decisions and management of finance.

Consider

In our analysis, and we do stress that it is our analysis, we can see a big shift in policy from integration to self-determination.