Kevin Berry

Walter Gropius must have allowed himself to dream up utopian scenes while working on the Dammerstock housing estate in 1929. The early photographs and perspective drawings of Dammerstock, including those made by Gropius, seem designed to evoke idyllic dreams. The viewer will encounter scenes in which, for instance, a chair in a dining nook is pushed away from the table, as if just used; or a single window is left open in the bedroom, indicating a breeze; or a stool is placed in the kitchen so that the appliances and ingredients, which are neatly stored in built-in bins and drawers, are all resting within arm’s reach. These scenes, perfectly framed and draped in natural light, ask the viewer to imagine themselves having dinner in the dining nook, with its large windows opened to a soft breeze and the night sky, to imagine enjoying a deeply restorative sleep in beds perfectly sized to the human figure and resting in uncluttered rooms, or to imagine easily preparing dinner in the modern kitchen.

It is easy to imagine how Dammerstock could have appeared to its architects like a “balm for factory workers returning from their labors in the hyperactive, energy-draining modern metropolis,” as one art historian has said of another housing estate of the same era.1 And yet, it is exactly Dammerstock’s ceaselessly attuned functionality—that same quality which upon first glance induces utopian dreams of a liberated, restored working class, inhabiting a world of domestic labor rid of drudgery—that allowed Dammerstock to be converted so easily from an instrument of liberation into an instrument of oppression.

In this essay, I examine the possibilities of an architectural resistance by looking back to Walter Gropius’s Dammerstock Siedlung, a workers’ housing settlement finished in 1929 in Karlsruhe, Germany. To Gropius, Dammerstock represented an architecture that was truly rationalized and humanized, not just economized and so made affordable for the working class. It is a dream his essay in the Dammerstock exhibition catalogue of 1929 reveals. In that essay, he says his design is “rational in the higher sense” and possesses the power to sculpt the complex and variegated “fabric of the community” (die Gemeinschaftsgebilde) in the modern city into a rationalized, more humanized whole.2 As such, Dammerstock stood not just as a balm to the worker of the city, but even more as an act of resistance against the irrationalities and inhumanities of the capitalist city itself. Yet as I have suggested, despite this grand vision, Dammerstock represents a failed attempt to build an architecture of resistance. Once built, it became a space that paradoxically reinforced those injustices which its architect, Walter Gropius, intended it to resist.

Dammerstock offers a cautionary tale. After all, it did not fail because it lacked socio-political effect, but because it had the opposite effect to that which was intended. It still had an effect. Accordingly, Dammerstock reaffirms the fact that even if architecture cannot resist hegemonic power as well as some of its more political practitioners may have wished, it does indeed possess some degree of political power over its subjects. Recognizing this, I will conclude that Dammerstock uncovers an important political task for architects today: making the general public more aware of the political messages implicit in the architecture of their built environments.

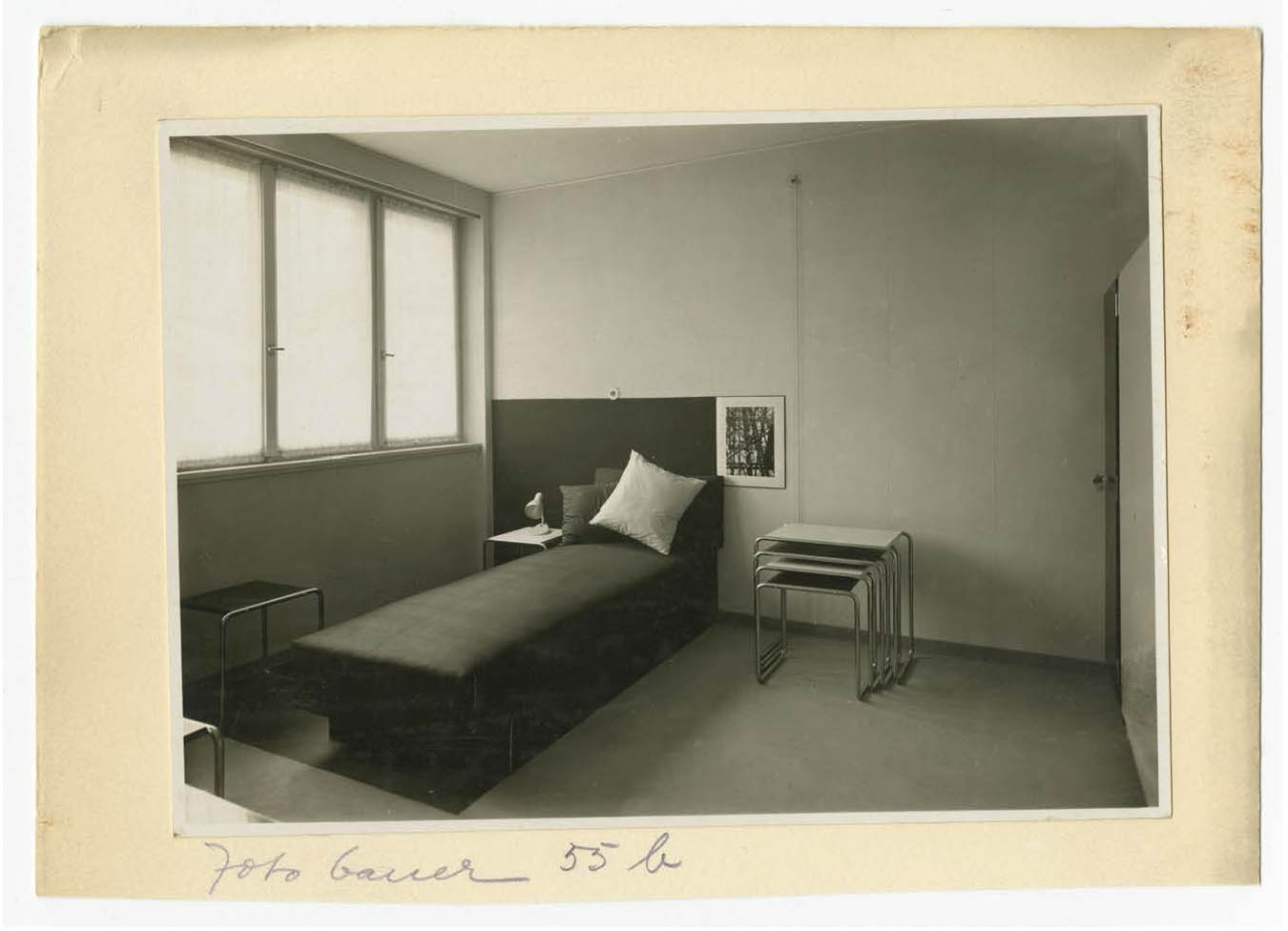

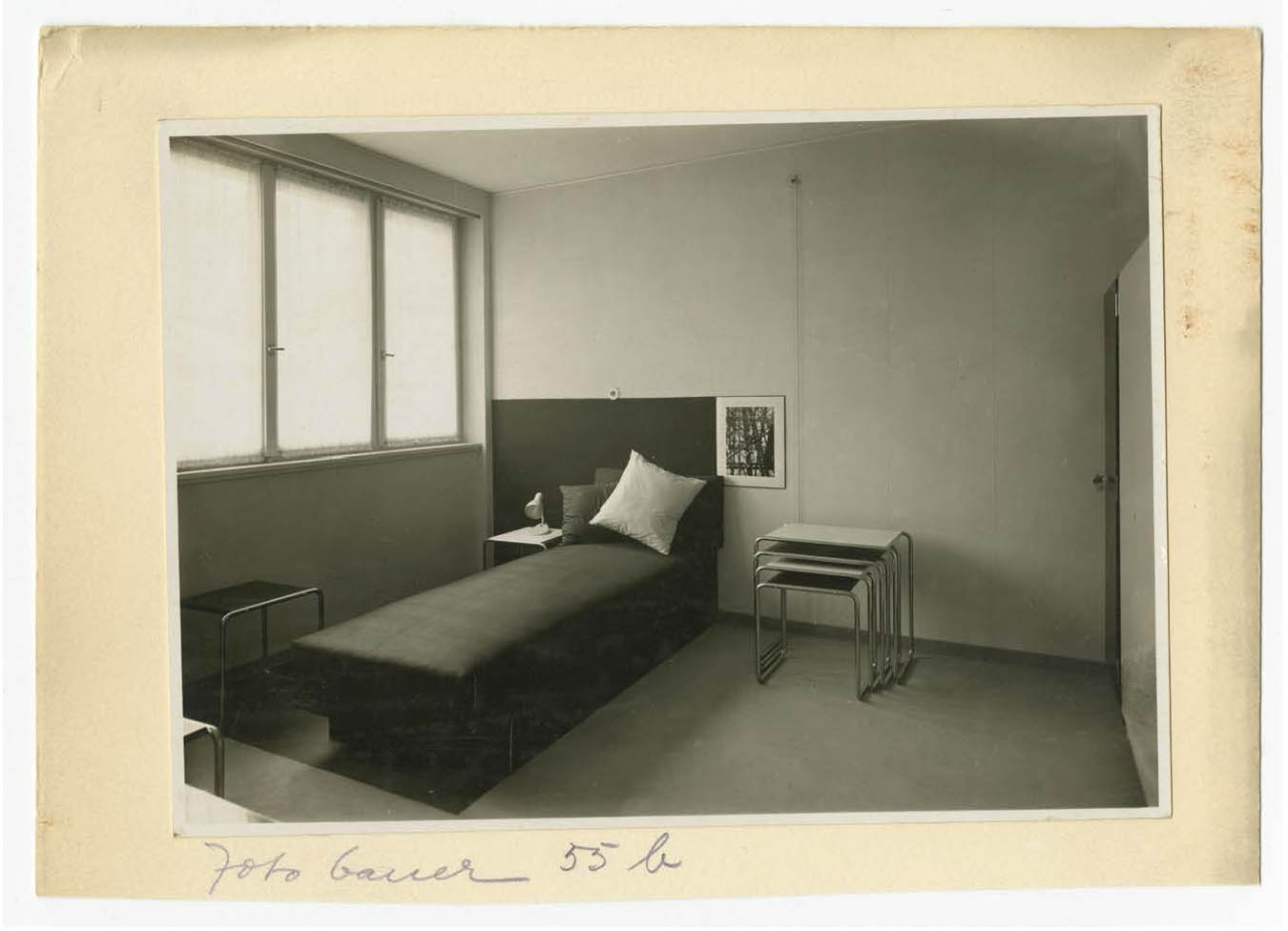

In 1926, in response to Germany’s ongoing housing shortage, the city of Karlsruhe designated a large site south of the central train station for the development of a working-class Siedlung (housing estate). It was to be partially financed through city funds.3 To popularize the project a design competition was held in 1928. The winning design was by Gropius, the modernist architect famous for having founded the Bauhaus in 1919. The final product provided Karlsruhe with 228 new dwelling units out of a projected 750.4 The seven rows of small, functionalist dwellings (Kleinwohnungen) were sized between 500 to 800 square feet, intended for families of five to eight, and held varying floorplans designed by several architects and designers alongside Gropius.5 These included Otto Haesler, who designed several other Siedlungen across Germany, Kurt Schwitters, who contributed graphic designs and advertisements, and Marianne Brandt, who contributed interior and furniture designs.6 Through this collaboration Dammerstock became a model of mass-produced dwellings, rationalized, functionalist, and sachlich (objective)—as modernist architects would have said in the 1920s.7 Even the several pieces of furniture included in the units, from beds to radios and kitchen appliances, were designed in a functionalist manner (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1: Walter Gropius. Bedroom Dwelling Group 9, Siedlung Dammerstock, Karlsruhe, 1928–9. Photographer: Atelier Bauer. Credit: Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

When the Siedlung neared completion in October of 1929, the city of Karlsruhe staged an exhibition titled “Die Gebrauchswohnung” (“the dwelling as a utility”), which displayed Dammerstock to the public as modern, rationalized type of housing that guaranteed an Existenz-Minimum (minimum existence) life.8

The issue which Dammerstock promised to solve was not new. Workers’ housing had been a problem across Europe for decades by the time Dammerstock was built, as Friedrich Engels’s 1845 The Condition of the Working Class in England demonstrated.9 Since the rise of industrial capitalism, factory owners and cities had failed to provide humane, sanitary, and safe living conditions for their workers. If workers were left on their own to find housing that they could afford, they would turn to overcrowded tenements. These tenements failed to provide even an Existenz-Minimum life for their occupants, as Heinrich Zille’s photography showed in the context of early twentieth-century Berlin, and, more famously, as Jacob Riis’s 1890 How the Other Half Lives showed in the context of New York City.10 Even within Germany, a nation late to unify and modernize, workers’ housing was an issue well before the twentieth century.11

In the early twentieth century, liberal and conservative architects alike lamented that city officials continued to allow more and more of Berlin’s notorious Mietskasernen (literally, “rental-barracks”) to be built.12 Despite the fact that article 155 of the 1919 Weimar constitution declared the right to adequate housing for all Germans, due to economic and political instability, the workers’ housing problem only worsened during the period of the Republic, and soon became a crisis.13 By 1929, overcrowded, cheaply constructed tenements had taken over much of eastern Berlin, leading one architectural critic to claim in his 1927 book Neues Wohnen, Neues Bauen (New Living, New Building), that a Mietskaserne “could kill a man as well as an axe.”14 Many cities across Germany faced the same problem.

In response, and especially following an upturn in the economy after the Dawes Plan of 1924 stabilized hyperinflation, several modernist-style Siedlungen were built across Germany.15 The Siedlungen of the architect Ernst May in Frankfurt-am-Main were minimal but rationalized, hygienic, filled with sun and space, often situated in park-like settings, and built by a well-coordinated industry.16 May’s “New Frankfurt” stood in stark contrast to the old Frankfurt with its twisted, crowded streets and old housing stock.

Similarly, Bruno Taut and Martin Wagner would construct many modernist Siedlungen in Berlin, like the “Horseshoe” Siedlung, so named because of its U-shaped plan which seemed to embrace sunlight and nature, in contrast to the dark cement courtyards and inner chambers of that city’s Mietskasernen. Karlsruhe-Dammerstock was certainly influenced by these works.

Gropius followed the precedent set by Ernst May in a second way as well. May positioned the architect as the manager of a “planned state capitalism,” and in Frankfurt May succeeded in controlling policy, securing government funds, and coordinating building industries so well that he was able to produce nearly 11,650 units (by Manfredo Tafuri’s count).17 Similarly but on a much smaller scale, at Dammerstock Gropius coordinated work between building trades and cartels, and positioned the architect as designer, city planner, and overall manager of the total building process.18

Dammerstock is therefore part of a long history of social housing, and its ideal of rationalization in style, interior design, and construction process is found in several Weimar-era housing estates. But as I will show, Gropius’s interest at Dammerstock is more than reform, and rationalization more than a stylistic preference. In this project, Gropius believed he was seizing an opening provided by the housing crisis to accomplish something greater, that he and his modernist colleagues were positioning architecture to stage a resistance against the prevailing socio-political hegemony.19 Specifically, Dammerstock was intended to resist two architecturally enforced injustices: class exploitation and the subjugation of women to domestic servitude. As Gropius’s first attempt to realize this vision, Dammerstock is intended as a design that does more than make the proletariat more comfortable within the confines of the prevalent socio-political hegemony of unplanned capitalism. Gropius designed Dammerstock as an architecture capable of resisting that power structure as a whole. It was to be an architecture capable of opening a space of resistance for the working class and women, a space through which these groups could attain political agency and subject-hood. As I will show, Gropius’s architecture ultimately failed to achieve these goals, but its failings nevertheless prove to be instructive for questions of architecture and resistance today.

To see Gropius’s design intention more clearly, as well as the two injustices he wished to resist, it is necessary to turn to his essay, “The Sociological Premises for the Minimum Dwelling of Urban Industrial Populations.”20 Written in 1929, the year after Gropius had stepped down from his role as director of the Bauhaus and while Dammerstock was being built, it can be read as a statement of intent for that Siedlung.21 In “The Sociological Premises,” Gropius hides his political ideals behind sociological terminology. Rather than communism, he advocates for “communal union” and “social individualism” and to avoid using the word capitalism, he argues against “egotistical individualism” and “rule by money in the industrial state.”22 Some of these terms, like “egotistical individualism,” were terms associated with Marxist theory in Gropius’s time.23 But the direct source for Gropius’s terms is a 1912 text written by the German sociologist Franz Carl Müller-Lyer.24

Like Gropius’s de-politicized theory, Müller-Lyer’s sociology conceals its broadly Marxist narrative under sociological terms. Müller-Lyer’s history of European humanity is, like Marx’s, the story of the progressive liberation of humanity through the powers of industry. From “rule by force in the warring state” (i.e., feudalism), humanity progressed to “rule by money in the industrial state,” (i.e., unplanned capitalism). Following this Marxist framework via Müller-Lyer, Gropius argues in “The Sociological Principles” that the industrial age promised to free humanity from its subjugation to nature—but only after industry has been freed from its domination by capitalists, who have selfishly bent industry to serve their own desire for individual profit. The factories, which should ease the burden of labor, have under the money economy of unplanned capitalism only intensified the burden of labor for the disenfranchised classes.

Gropius’s apolitical framework is troubling in many ways.25 Nevertheless, his message is clear. When “the propertied class rules, the masses become impoverished.” Under unplanned capitalism, “The masses are trained to labor, but the rights of individuals are suppressed.”26 In his 1929 essay Gropius is advocating for the socialization of industry. Industry should not be ruled by money, nor should laborers be exploited for private profit. Industry should be placed in the service of fulfilling humanity’s true needs, which can be defined to a precise degree by sociology, Gropius believes. This is the goal of “rationalization” for Gropius. Rationalization was not an architectural style alone; it was a social vision which would be achieved once industry had been made a liberating and fulfilling, rather than oppressive, force. This is why he defines “rationalization” in that essay as “a major intellectual movement in which the actions of the individual are gradually being brought into beneficial relation with the welfare of society as a whole, a concept which transcends that of economic expediency for the individual alone.”27

At the time of writing “The Sociological Premises,” Gropius’s ultimate goal, architecturally speaking, was a residential typology which would consist of a complex of Kleinwohnungen (small apartment dwellings surrounding a large central building that housed socialized domestic services). Though Gropius avoided politics and even any political terms like “socialism” or “communism” in “The Sociological Premises” as stated above, certain similarities to Russian communist housing types like the “Dom-kommuna” as it was advocated by two of Gropius’s colleagues, Karel Teige and El Lissitzky, can be detected in Gropius’s vision.28 At one point in his essay Gropius even declares, “every adult shall have his own room, small though it may be!”29 Eventually, he hoped, society would come to be built around types of institutions more capable of satisfying individuals’ desire for “social intercourse” than the private, familial home.30 This shows that Gropius was imagining Dammerstock as a first step towards a new architectural typology for Germany which would stand, as a step towards a socio-political rationalization, in resistance to the irrational injustices of capitalism. Specifically, Gropius imagined his design would resist two injustices perpetuated by the patriarchal-capitalist socio-political system which he describes in “The Sociological Principles” as an “egotistical individualism”: first, class exploitation, and second, the exploitation of women.

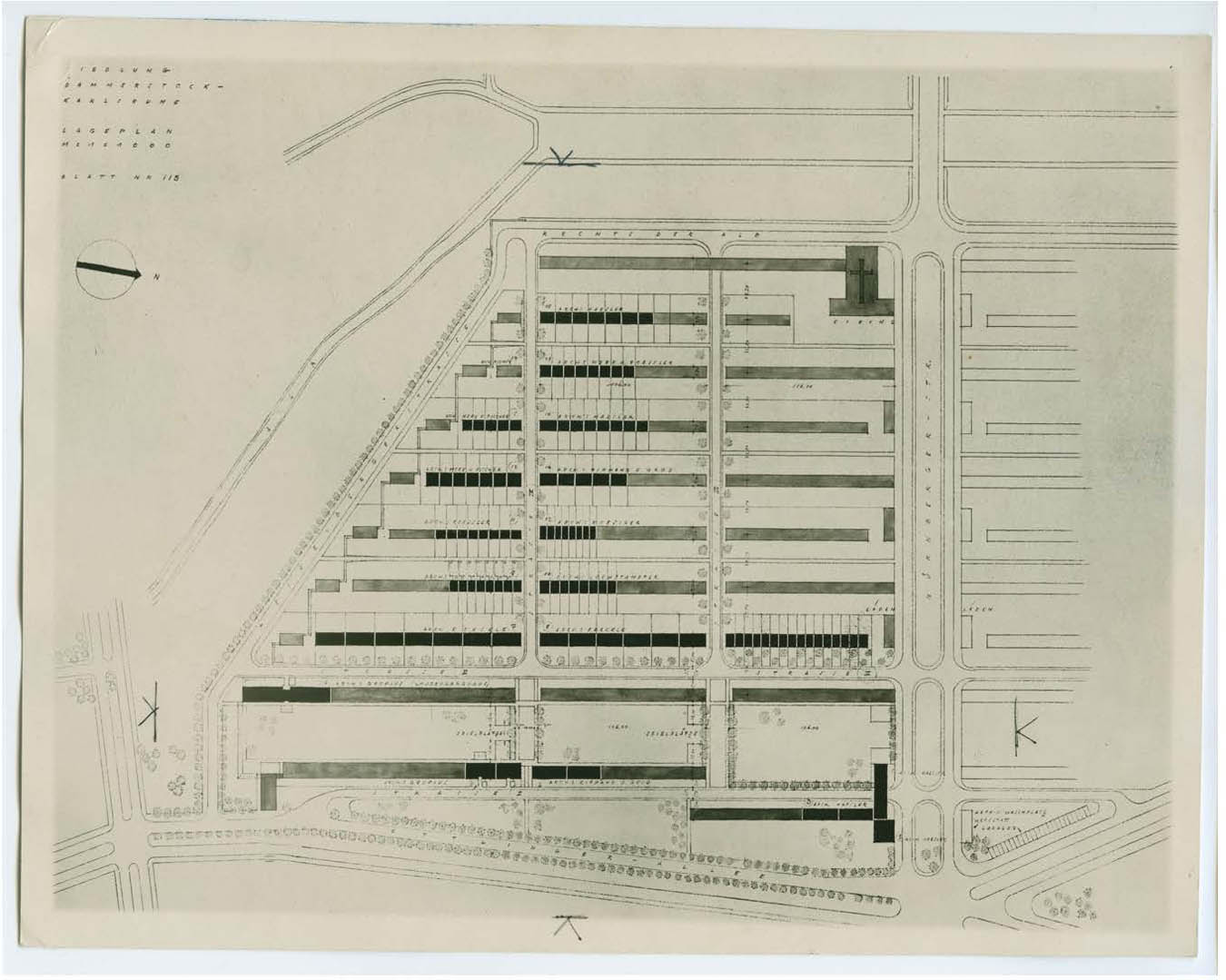

First, Dammerstock was intended to resist class exploitation by socializing more of the built environment. Remnants of his intention remain in Dammerstock as it was built. For instance, in the northeast corner of the site is located a centralized building with shared utilities and space for offices. It holds the heating equipment for the housing complex as well as a shared laundry facility—a symbol of socialized domestic labor.31 Another remnant of his resistant desire is visible in aerial photography and in some renderings of the site plan, where the entire complex appears as a communal green space. The long, narrow strips of dwellings stand uninterrupted in gardens like permeable screens open on both sides, as if they were cells in a single common space rather than isolated, private instances, with their backs turned on their neighbors. Yet another remnant can be found in the fact that a church was placed in the northwest corner, if one is permitted to see in the inclusion of a religious building the expressionist dream of a “cathedral of socialism,” an idea found in Gropius’s writings around the time of the 1919 Bauhaus manifesto (Figure 3.2).32

Figure 3.2: Walter Gropius. Site plan of Siedlung Dammerstock, Karlsruhe, 1928–9. Credit: Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Dammerstock not only held symbols of resistance to capitalism’s oppressions, it also promised a real change for the working class. The substandard conditions within the Mietskasernen had inhibited workers from gaining the strength to revolt. Tenements forced workers into housing with only a quasi-legal status because violations from overcrowding or unsanitary conditions could be used as excuses for eviction or demolition. Dammerstock was intended to realize a space that enabled greater autonomy and solidarity for the working class, because in theory it would socialize domestic labor and build communally owned housing. Allowed to dwell in a space which forced the city to recognize them as legitimate and permanent members of the political community, the working class would be placed in a better position to unite and resist their oppressors.

Further, the construction method at Dammerstock promised a new socialized building industry with the architect acting as its director. Positioning the architect as city planner appeared to cut out the city bureaucracy, which seemed to bend so easily to the dominant class interests. The rationalization of the domestic sphere at Dammerstock, accomplished by the architect in complete control of the design and construction, was a prefiguration of the society-wide rationalization of life which Gropius believed was occurring at the time. This is an idea he expresses in both “The Sociological Principles” and in the Dammerstock, exhibition catalogue essay. In the latter, he explicitly confirms that rationalization as something much more than an architectural or economic phenomenon. It is in his vision a “great spiritual movement” (“grossen geistigen Bewegung”) happening across society, in resistance to the irrationalities of his day’s capitalist and patriarchal hegemony.33 Architectural rationalization, like the kind at Dammerstock would serve as a catalyst in a much larger, world-historical transformation occurring in modern society as a whole. His “Sociological Principles” essay indicates his belief in this, and that if more and more housing in the Dammerstock typology were built, then a socialized, rationalized way of life could infiltrate Germany’s cities. More and more of society would be socialized and the amount under the control of private industry would continue to decrease. A socialized housing industry, Gropius theorized in the “Sociological Principles,” would lead to a progressive reformation of society as a whole, as workers and women would come to gain more and more economic, social, and political power. Gropius theorized that this was the natural path—an “evolutionary development,” in his words—for industrialized society.34 The success of Ernst May in Frankfurt-am-Main and Martin Wagner in Berlin must have made this utopian transformation of society into a more rational order through architecture seem a real possibility to Gropius. One can see how the idea of architectural rationalization—the leading design idea behind Dammerstock, as I have argued—appeared to Gropius in 1929 as a means of resistance for the working class in the face of class exploitation.

Dammerstock promised to resist the patriarchal subjugation of women to domestic servitude by socializing domestic labor and ending the patriarchal family structure. The era of “communal union” would not be achieved until women also attained autonomy and subject-hood, as the patriarchy was another form of the same repressive “egotistical individualism” which exploited the working class, too. As the first prototype for a new residential typology, Dammerstock would also allow for, in Gropius’s words, “the awakening and progressive emancipation of woman.”35 Still following the sociology of Müller-Lyer, Gropius writes in “The Sociological Premises” that the patriarchal family structure, which relies on “the subjugation of woman by man,” is a residue of the “enslavement of man by the ruler” that occurred in the past epochs of feudalism.36

Traditional housing types, Gropius’s 1929 essay implies, reproduce the patriarchal family structure and its corresponding ideology, and thus perpetuate the subjugation of women to domestic servitude. The large, single-family, “ancestral” home, Gropius claims, is made to enforce a socio-political system which places the responsibility for raising the children, caring for elderly relatives, meal preparation, and cleaning, on the family. Gropius indicates that housing type itself is designed for a private economy to take place inside the home, one which the father and sons would traditionally have been excused from, due to their work in a specific trade. And so the management of the private domestic economy would fall to the responsibility of the woman. In conjunction with this economic arrangement, other architectural reinforcements of the patriarchy, such as the prevalence of social clubs and other public spaces exclusively for men, proliferated.37

According to Gropius, this patriarchal system would be prevented by smaller, Existenz-Minimum domiciles clustered around a “centralized master household” which would presumably hold communal child-rearing services, laundry facilities, businesses, and social clubs for both women and men, as is found in other utopian schemes for social palaces and condensers. Dammerstock was in Gropius’s mind a prototype of just such an architectural condition. Thus it stands as an image of the architecture he must have imagined when speaking, in “The Sociological Premises,” of a typology which would free “woman” for an equal intellectual and economic “partnership with man.”38

The patriarchal socio-political system is reinforced by architecture, Gropius has theorized; Dammerstock would resist that system—or so Gropius wished—by building an architecture which would disallow the spatial practices necessary for a patriarchal system. The aforementioned shared laundry facility at the northeast corner of the site

stands as a symbol of socialized, industrialized domestic labor (see Figure 3.2). Dammerstock is also designed to have highly efficient “Frankfurt” kitchens, following the precedent set by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky working with Ernst May in the mid–1920s.39 Such Taylorized kitchens were intended to save energy and time in food preparation and, by saving time, liberate the woman from the kitchen. As I will note below, while the intentions behind these design choices were potentially revolutionary, it quickly became apparent that this efficiency in fact only reinforced the patriarchal, sexist division of labor within the home more rigorously.

Still, it should be noted, many aspects of Dammerstock lived up to the project’s modernist intentions. The use of space was more efficient: cellars were designed for ease of access from the kitchen; appliances were exposed for easy maintenance and cleaning; vegetable gardens could be planted at the backdoor of most units. In terms of the floor plan, not a single inch is wasted, and flat roofs were justified as a way to prevent the waste of space under sloping eaves (see Figure 3.4). Narrow beds, nesting end tables, and lightweight chairs free more floor space (see Figure 3.1). Each unit is equipped with electric appliances, like those advertised in the back of the exhibition catalogue, and each kitchen has a gas stove.

In short, Gropius believed that positive social change would follow from this design. It was the first step in a process in which, Gropius writes, “One product of domestic industry after another is wrested from the family and transferred to socialized industry.”40 With this new, social form of dwelling, marriage would continue to change from a “compulsory institution sanctioned by the state and the church,” to a “voluntary union of persons who retain their intellectual and economic independence.”41 This efficiency was intended to realize a greater degree of freedom and autonomy for women and the working class. But as will soon be seen, Gropius’s intentions went awry.

As explained above, rationalization was in Gropius’s mind a means of resistance. But when realized, Dammerstock accomplished just the opposite of Gropius’ intention. Gropius’s rationalized design inadvertently created an architecture that subjected its occupants to an even more potent repressive spatial regime. It became a symbol not of resistance to but of complicity with the Arbeitsideologie (work ideology) of capitalism.42 As soon as it was built, the Dammerstock Siedlung became yet another symbol of the oppressive socio-political system it was supposed to resist.

For the ruling classes viewing Dammerstock from the outside, the design symbolized an economic gain; it promised a more profitable and sturdier future for capitalism, a healthier, more satiated workforce less motivated to resist. The potential for this interpretation of the project was already evident in 1929, when Dammerstock opened as an exhibition. An image of the Siedlung under construction, taken from the west end of the site facing east, shows the view across the site in the months before its opening (Figure 3.3). The exterior form is extremely restricted, with its seven rows rigorously adhering to the Zeilenbau (line-building) technique. There is no color, no ornament; the exterior is uniformly white, with thin lines of gray running along the foundation of some of the buildings. Large windows go unframed under flat roofs. These rows of solemn repetition appear like soldiers on the march, or like seven assembly lines working in tandem, poised to manufacture a healthy life among its occupants. It is more an image of a smoothly running factory floor than an image of a liberated domestic landscape.

Figure 3.3: Walter Gropius. Exterior view of Siedlung Dammerstock, Karlsruhe, 1928–9. Photographer: Adolf K. Fr. Supper. Credit: Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Further, against Gropius’s intentions, Dammerstock could be read as the image of a sanitized working class. Combined with bands of large windows, the Zeilenbau technique allows for full sunlight, and the exhibition catalogue declares that Dammerstock has not only “Kein Raum ohne Sonne!” (“no room without sun!”) but that each room is placed so as to receive sun at the right time of day: the bedrooms face east for morning light, while living rooms are placed so as to receive midday and evening light.43 Following this idea as if it were a doctor’s order, the gardens and roof decks at Dammerstock evoke Alvar Aalto’s 1933 Paimio Sanatorium as much as Le Corbusier’s 1927 Weißenhofsiedlung roof terraces. The entire complex is like the sunbathing deck of a sanatorium, airing out the working class after what many saw as their long and degenerative tenure in the recesses of tenement buildings, cellars, and attics.

To the subjugated occupants within, Dammerstock wound up enforcing an ideology of passive acceptance—again, another result very different from Gropius’s intentions. The restrictive nature of Dammerstock is visible in the Zeilenbau exterior as well as the Existenz-Minimum interior. The units are typically two stories, consisting of the small Frankfurt-style kitchens next to a combined living and dining room, with two bedrooms and one bathroom upstairs. Beds are sized perfectly to the human body, and rooms are furnished with machine-aesthetic, tubular-steel furniture (see Figure 3.1 and 3.4).

Figure 3.4: Walter Gropius. Elevation, plan, and section of Dwelling Group 9, Siedlung Dammerstock, Karlsruhe, 1928–9. Credit: Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

In one unit, designed by Gropius himself, even the radio is designed to fit in one spot and one spot only, and the same seems true of the plants and bookshelves in another.44 The envelopes of the kitchen spaces are wrapped as tightly as possible around a single set of predetermined actions. The modern appliances produced by German firms such as AEG and Junkers are integral components in the spatial composition.45 In one layout—Group 11—racks are designed to fit a standardized set of dishes or, in some cases, utensils. Nothing, not even a fork or spoon, can be added or subtracted. Each dwelling is composed without any excess, without any breaks or gaps between the objects of use.

The design was supposed to yield a greater degree of autonomy and political agency to the working class. Yet the rigorously functional design turned every inch of the home into an assembly line, pre-determining how the occupants would act as they would move through their daily routines. Rather than allowing the working class to socialize domestic life and gain autonomy, the design effectively turned the inhabitants’ daily routines into private, Taylorized assembly lines and made even personal life a matter of endless production and consumption; rather than socializing domestic labor, Dammerstock only intensified the ideology of domesticity as a natural form of labor for women. One critic noticed the self-defeating nature of this vision early on. In his 1930 review of Dammerstock, Adolf Behne claimed that Gropius had turned the architect into a dictator. At Dammerstock,

the human is turned into a concept, a figure. The human is to dwell and through the Wohnen become sound, and the exact Wohndiät [life-diet] is prescribed to him in detail. He must … go to bed facing east, eat and answer mother’s letter facing west, and the dwelling becomes so organized that he cannot in fact do it any other way. […] Here in Dammerstock the human becomes an abstract dwelling-being, and over all the very well-intentioned specifications of the architects, in the end he wants to cry out, “Help … I’m being made to dwell!”46

Dammerstock enforces a Wohndiät, a restriction of life, by being so rigorously designed that it becomes suffocating. With the space of each room arranged so rigorously around a single particular activity, it barred the occupants from ever stepping away from a routine of production, and accordingly it stripped its subjects of what little control over their own lives that they held prior to settling into the rationalist architecture. The architecture prevents its occupants from freely occupying any space, from resisting by their own volition, from obtaining any degree of autonomy. The architecture, against Gropius’s intentions, could also speak to its occupants in such a way that it reminds them that they are subjugated to routines of production, and reinforces the subjugation of women to domestic servitude even more effectively than the Mietskaserne of Berlin were able to. It only more efficiently traps them in routines of production and converts them into more efficient consumers, even if they could not consume as much as the bourgeois classes above them. Here is another sense in which Dammerstock places its occupants on a Wohndiät: their dwellings, or Wohnungen, will never be as fully stuffed as their wealthier neighbors’.

In the end, the idea of rationalization, resistant and liberating in Gropius’s vision, was all too easily converted into an instrument for perpetuating the oppressive system it hoped to resist. By making class exploitation appear moral to the oppressors and inevitable to the oppressed, while also making the domestic subjugation of women appear unproblematic and unburdened because it was now aided by modern appliances, Dammerstock worked against Gropius’s intentions. Dammerstock’s sachlich design only left its occupants more susceptible to exploitation and subjugated them to a Wohndiät.

Dammerstock confirms the conclusion of the neo-Marxist architectural historian Manfredo Tafuri: the modernist ambitions for an architecture of resistance and social change were motivated by a naïve utopianism which was doomed to be a determinate failure socially.47 As Michael Hays explains, Tafuri has shown that architecture becomes, “when it is most itself—most pure, most rational, most attendant to its own techniques— the most efficient ideological agent of capitalist planification and unwitting victim of capitalism’s historical closure. In a certain sense … architecture’s utopian work ends up laying the tracks for a general movement to a totally administered world.”48 This is the first lesson of Dammerstock. Gropius believed he could act as a social engineer and attempted to build an environment which would reshape individuals’ actions and beliefs for the better. But this is a self-defeating idea, amounting to the claim that individuals can be forced to their freedom. Any attempt at resistance through functionalism, intended to act as a kind of social engineering, will backfire.

The second lesson is that if Dammerstock is a reminder of the power of architecture to reinforce the status quo, despite even the best intentions, it is also a reminder of the political power of architecture. As theorists like Peggy Deamer, Keller Easterling, Nadir Lahiji, and Douglas Spencer have argued, architectural ideology remains a powerful force that reproduces submission to the socio-political injustices of neoliberalism today.49 Architectural ideology does affect the public which inhabits it, just as it did in the case of Walter Gropius’s Dammerstock nearly ninety years ago, despite his best efforts to build an architecture of resistance. Unintentionally, Dammerstock wound up symbolizing the strength of the capitalist system to the residents of Karlsruhe, Germany in 1929. Today, in the context of globalized neoliberalism, architectural symbolism seems to have become an even more powerful tool for reproducing capitalist ideology. Neoliberal architectural symbolism of today—found in skyscrapers, city design, and even border walls—reinforces injustices like the growing gap between wealthy and poor as well as socio-political exclusions along lines of class, gender, nationality, and several other means of “identitarian inscription” across the globe.50

Recognizing this, it becomes clear that at least one act of resistance is possible for architects today. Architects may not be able to design socio-political change or even to build an anti-ideological architecture as Gropius had hoped. But they are among the few members of society today who specialize in discerning the ideological codes of the built environment. Gropius’s “Sociological Premises” testifies to this unique skill, as it can be read as a brilliant decoding of the architectural ideology of its time, similar to the decoding exercises found in Robert Venturi and Denise Scott-Brown’s Learning from Las Vegas over forty years later.51

Armed with this unique skillset, architects remain in a unique position to make the general public more aware of the injustices that contemporary society’s spatial practices silently enforce. Architects today can resist by working to expose today’s architectural ideology to the subjects affected by it most—not other architects, but the general public. One final lesson from Dammerstock, then, is that even if architecture cannot turn the profession itself into a protest or a form of social engineering, architects can focus on teaching the public how to better resist the Wohndiäten (to return to Adolf Behne’s term) that architecture reinforces. Putting this idea into practice has the potential to create a public that is even more resistant to today’s ideologies of neoliberalism and nationalism than were those of the past.

1Joan Ockman, “Three Monuments to the Norm,” Trans 24 (February 2014), 134.

2Ausstellung Karlsruhe Dammerstock-Siedlung: Die Gebrauchswohnung, Reprint (Karlsruhe: Miller-Gruber, 1992), 9.

3The financing model devised for Dammerstock was relatively successful, and came to be known as the “Karlsruhe System” among city planners. Brigitte Franzen, Die Siedlung Dammerstock in Karlsruhe 1929: zur Vermittlung des neuen Bauens (Marburg: Jonas, 1993), 11, 15, 21.

4Brigitte Franzen, Die Siedlung Dammerstock in Karlsruhe 1929: zur Vermittlung des neuen Bauens (Marburg: Jonas, 1993), 18, 25.

5Ausstellung Karlsruhe Dammerstock-Siedlung, 16.

6Peter Schmitt, “Was braucht der Mensch? Zur Einrichtung der ‘Gebrauchswohnung,’” in Neues Bauen der 20er Jahre: Gropius, Haesler, Schwitters und die Dammerstocksiedlung in Karlsruhe 1929, eds Brigitte Franzen and Peter Schmitt (Karlsruhe: Sonstige, 1997), 139–58.

7On the term “sachlich,” see Harry Mallgrave, “From Realism to ‘Sachlichkeit,’” in Otto Wagner: Reflections on the Raiment of Modernity (Santa Monica, CA: Getty Research Institute, 1996), 281–322.

8Ausstellung Karlsruhe Dammerstock-Siedlung, 1.

9Friedrich Engels, The Condition of the Working Class in England, ed. David McLellan (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009).

10Jacob Riis, How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York, ed. Charles A. Madison (New York: Dover Publications, 1971).

11Mitchell Schwarzer, German Architectural Theory and the Search for Modern Identity (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995); Eduard Führ and Daniel Stemmrich, Nach gethaner Arbeit verbleibt im Kreise der Eurigen. Arbeiterwohnen im 19. Jahrhundert (Wuppertal: Peter Hammer, 1987).

12See, for instance, Ludwig Hilberseimer, Metropolisarchitecture, ed. Richard Anderson (New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2014); Karl Scheffler, Die Architektur der Grosstadt (Berlin: Bruno Cassirer, 1913).

13Dan P. Silverman, “A Pledge Unredeemed: The Housing Crisis in Weimar Germany,” Central European History 3, no. 1/2 (1970), 112–39.

14Adolf Behne, Neues Wohnen, Neues Bauen (Leipzig: Hesse & Becker Verlag, 1927), 4.

15On the relation of the Dawes Plan to architecture see Manfredo Tafuri, “Sozialpolitik and the City in Weimar Germany,” in The Sphere and the Labyrinth: Avant-Gardes and Architecture from Piranesi to the 1970s (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995), 203.

16On “The New Frankfurt,” see Susan R. Henderson, Building Culture: Ernst May and the New Frankfurt Am Main Initiative, 1926–1931 (New York: Peter Lang, 2013); David H. Haney, When Modern Was Green: Life and Work of Landscape Architect Leberecht Migge (New York: Routledge, 2010).

17Manfredo Tafuri, The Sphere and the Labyrinth: Avant-Gardes and Architecture from Piranesi to the 1970s (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995), 206, 222, 231.

18Tafuri, “Sozialpolitik and the City in Weimar Germany,” 212.

19For a definition of hegemony in relation to architecture, see Demetri Porphyrios, “On Critical History,” in Architecture, Criticism, Ideology, ed. Joan Ockman (Princeton, N.J: Princeton Architectural Press, 1985), 16.

20English translation taken from Walter Gropius, Scope of Total Architecture (New York: Collier Books, 1970), 91–102.

21Gropius’s speech was originally presented at CIAM II in Frankfurt. Sigfried Giedion read the speech in Gropius’s absence. Eric Mumford, The CIAM Discourse on Urbanism, 1928–1960 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000), 35. Gropius’s contribution to the Dammerstock exhibition catalogue provides further evidence that “The Sociological Premises” essay can be read as a manifesto for Dammerstock, as the exhibition catalogue essay repeats many of its key claims.

22Gropius, Scope of Total Architecture, 92.

23Andrew Feenberg, The Philosophy of Praxis: Marx, Lukács and The Frankfurt School (London: Verso, 2014), 31.

24Tanja Poppelreuter, “Social Individualism: Walter Gropius and His Appropriation of Franz Müller- Lyer’s Idea of a New Man,” Journal of Design History 24, no. 1 (2011), 37–58.

25For a helpful introduction to Gropius’s relation to capitalism and politics, see Robin Schuldenfrei, “Capital Dwelling: Industrial Capitalism, Financial Crisis and the Bauhaus’s Haus am Horn,” in Architecture and Capitalism: 1845 to the Present, by Peggy Deamer (New York: Routledge, 2014), 71–95.

26Gropius, Scope of Total Architecture, 92.

27Gropius, 91–3.

28Karel Teige would contribute an essay for the 1930 CIAM III publication which covered the same topic as Gropius does in “The Sociological Premises.” Teige’s essay was titled “The Housing Problem of the Subsistence Level Population.” Mumford, The CIAM Discourse on Urbanism, 1928–1960, 37, 53.

29Gropius, Scope of Total Architecture, 99. Emphasis in original.

30Gropius, 94.

31Dolores Hayden, The Grand Domestic Revolution: A History of Feminist Designs for American Homes, Neighborhoods and Cities (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1982).

32On the cathedral of socialism idea, see Marcel Franciscono, Walter Gropius and the Creation of the Bauhaus in Weimar: The Ideals and Artistic Theories of Its Founding Years (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1971), 113.

33Ausstellung Karlsruhe Dammerstock-Siedlung, 9.

34Gropius, Scope of Total Architecture, 96.

35Gropius, 95.

36Gropius, 92.

37Gropius, 94.

38Gropius, 92, 96.

39On the Frankfurt Kitchen, see Sophie Hochhäusl, “From Vienna to Frankfurt Inside Core-House Type 7: A History of Scarcity through the Modern Kitchen,” Architectural Histories 1, no. 1 (October 1, 2013).

40Gropius, Scope of Total Architecture, 93.

41Gropius, 96.

42Tafuri, “Sozialpolitik and the City in Weimar Germany,” 197.

43Ausstellung Karlsruhe Dammerstock-Siedlung, 11.

44Schmitt, “Was braucht der Mensch? Zur Einrichtung der ‘Gebrauchswohnung.’”

45See advertisements in Ausstellung Karlsruhe Dammerstock-Siedlung.

46Adolf Behne, “Dammerstock,” Die Form 5, no. 6 (1930), 164.

47Fredric Jameson, “Architecture and the Critique of Ideology,” in Architecture, Criticism, Ideology, ed. Joan Ockman (Princeton, N.J: Princeton Architectural Press, 1997), 53, 59.

48K. Michael Hays, Architecture Theory Since 1968 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000), xii.

49Peggy Deamer, Architecture and Capitalism: 1845 to the Present (London: Routledge, 2013); Keller Easterling, Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space (New York: Verso, 2016); Nadir Lahiji, ed., Can Architecture Be an Emancipatory Project? Dialogues on Architecture and the Left (Washington: Zero Books, 2016); Douglas Spencer, The Architecture of Neoliberalism: How Contemporary Architecture Became an Instrument of Control and Compliance (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016).

50Erik Swyngedouw, “On the Impossibility of an Emancipatory Architecture,” in Can Architecture Be an Emancipatory Project? Dialogues on Architecture and the Left, ed. Nadir Lahiji (Washington: Zero Books, 2016), 58.

51Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi, Learning from Las Vegas (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1972).