Nina Lübbren

The artistic range of responses to authoritarian regimes has varied from utter conformism, as exemplified by the New Year’s posters distributed to communities during the decade of the People’s Republic of China’s Cultural Revolution, to overt political critique, such as that found in the anti-fascist photomontages of John Heartfield, produced in exile from Germany during the 1930s.1 Those who do not emigrate are obliged to come to terms with power and authority in some form or another. Resistance is one way among others to imagine how art might relate to power in a totalitarian environment. This chapter examines three German sculptors’ creative practice under National Socialism. Continuing as a professional sculptor during the fascist regime necessitated at least a degree of accommodation to circumstances lest one be punished with Berufsverbot, that is, be prohibited from publicly exhibiting and selling work or from teaching art. From the first months after the National Socialist take-over it was clear that persons who were identified as communists or Jews were dismissed from posts and forbidden to practice; the case with regard to the formal or iconographic language of art works themselves was much less clear-cut. The careers and works of the sculptors Oda Schottmüller, Hanna Cauer, and Milly Steger allow us to trace a range of responses to the power of authoritarian art policy, from political resistance to aesthetic conformism and opportunist negotiation.

The monumental, state-sponsored character of much National Socialist sculpture would seem to make it difficult to use this medium in order to “resist” the established order. Sculpture, one might say, resists resistance. Sculpture would appear to be particularly susceptible to co-optation by authoritarian systems because of its potential as propaganda in the form of monuments in public spaces.2 Ellen Schwarz-Semmelroth, editor of the official National Socialist women’s journal NS.Frauen-Warte, wrote of the 1942 Great German Art Exhibition in Munich: “Heroic demeanor, toughness and discipline have made human souls more receptive than ever to monumental form and content.”3 In its public address, sculpture differed from painting, and James van Dyke notes, sculpture in fascist Germany was in many ways treated as superior to the “hyper-refined” products of modern painting.4 In 1942, art historian Hans Weigert formulated the difference between painting and sculpture thus: “Easel painting is suited to a room, sculpture to the public square. Inside the room, there lives the individual, the square absorbs the crowd.… Sculpture radiates out into a space and can thereby dominate many people.”5 I take Weigert’s notion of domination not only to pertain to sculpture’s physical command of space but also to its psychological authority and emotional interpellation. Sculpture was deemed on a par with architecture in its public reach and was often conceived as part of an architectural urban environment.6 However, figurative sculpture (and there was no other in National Socialist Germany) could operate at an affective level in a way that architecture could not. National Socialist art historian Johannes Sommer wrote in 1943:

Of all the visual arts, sculpture is the one medium most capable of forming an immediate and replete image of the human. Sculpture retains the essence of ephemeral being in non-perishable material and in spatial tactility. A sculptor’s work reveals the force of life that is at work within humans and elevates individual existence into the greater circle of creation.7

Given the preponderant focus of the literature on public sculpture and on large monumental work in particular, it is worth recalling that the public arena is not the only space where sculpture can unfold its affective impact. Sculpture can also be located in semi-public and domestic spaces where it could elicit more intimate responses. Indeed, the majority of sculptural works produced during the fascist era were not large-scale monuments but small-scale figurines, mostly portraits or animal motifs.8 The Great German Art Exhibitions held between 1937 and 1944 may be taken as a measure of mainstream and officially sanctioned practice. In 1938, of the circa three hundred and fifteen sculptures shown at the Exhibition, only forty-seven or less than one-sixth were life-size or larger-than-life. Monumental statues were set up in the central halls near the ground-floor entrance but the overwhelming majority of three-dimensional works were statuettes, figurines, and medals, displayed in glass cases and on tables and plinths in the top-floor galleries. Well over half of the sculptures were of animals, heads, or busts rather than of full-scale nudes or draped figures.9 Partly this is a reflection of the commercial character of the Great German Art Exhibitions. All the art on show was for sale, ranging in price from under one hundred to two hundred thousand Reichsmark.10 It is to be assumed that small-scale works were affordable and appealed to a larger segment of the potential buying public than monumental statues, which were the purview of official patronage.

The three artists I have chosen exemplify positions on a possible spectrum ranging from apparently absolute conformity to seeming absolute resistance. All three artists remained in Germany and carried on their careers, exhibiting in private galleries or (from 1937) in the annual, state-sponsored Great German Art Exhibitions in Munich, being reviewed in the press, taking part in competitions, or bidding for commissions. These sculptors’ cultural practices span a range from official patronage and apparent conformism (Cauer) to pragmatic adaptation (Steger) and political opposition (Schottmüller). The case of Steger points to the ambivalence of National Socialist cultural policy itself, a shifting ideological field of proscriptions and pronouncements that posed a challenging terrain for any individual to negotiate. These three cases are relevant to issues of cultural resistance because they point to the parameters within which resistance could take place within a fascist context; they show that there was considerably more leeway for sculptors to work than would perhaps be expected within a so-called totalitarian state but that there were also definite and lethal limits to that leeway. Each example also opens up the issue of to what extent the work or the person’s activities could be considered as resisting, conformist, or anywhere in between.

Oda Schottmüller (1905–43), niece of art historian Frida Schottmüller, comes closest to having participated in a resistance movement.11 In September 1942, Schottmüller was arrested, along with 120 other persons, for illegal broadcasts to the Soviet Union and the distribution of rebel leaflets. Schottmüller was also accused of being affiliated with a communist “Red Orchestra” espionage and resistance group in Berlin.12 In August 1943, she was executed by decapitation, having been condemned to death for “assisting in the preparation of activities of high treason and favoring of the enemy.”13

Schottmüller was a sculptor, mask maker, and dancer. She studied dance at the Berlin dance school of Vera Skoronel and Berthe Trümpy, both students, among others, of Mary Wigman. Schottmüller also studied sculpture with Milly Steger in Berlin and, in the early 1930s, began to design costumes and wooden masks. She integrated these masks and outfits into her own dance performances (Figure 4.1).

Her first solo performance was in 1934. The eccentric dance performances took up the legacy of 1920s Expressionist Ausdruckstanz or “expressive dance.” Throughout the 1930s, Schottmüller received favorable press reviews, including from official quarters. In 1937, dance critic Fritz Böhme of the Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung was asked to write a reference for the Ministry of Propaganda’s dance caucus. Böhme wrote: “I deem Oda Schottmüller to be a dancer of unusually intensive powers of experience, that is, of a devotion to her interior felt visions, that seem to her elementary and necessary …”14 Böhme recommended Schottmüller to the Ministry as of above average talent and “desirable.”15

Figure 4.1: Oda Schottmüller, Alraune (Mandrake), c. 1941. Photograph of Oda Schottmüller dancing and wearing a mask of her own making © Archiv Susanne und Dieter Kahl, Berlin.

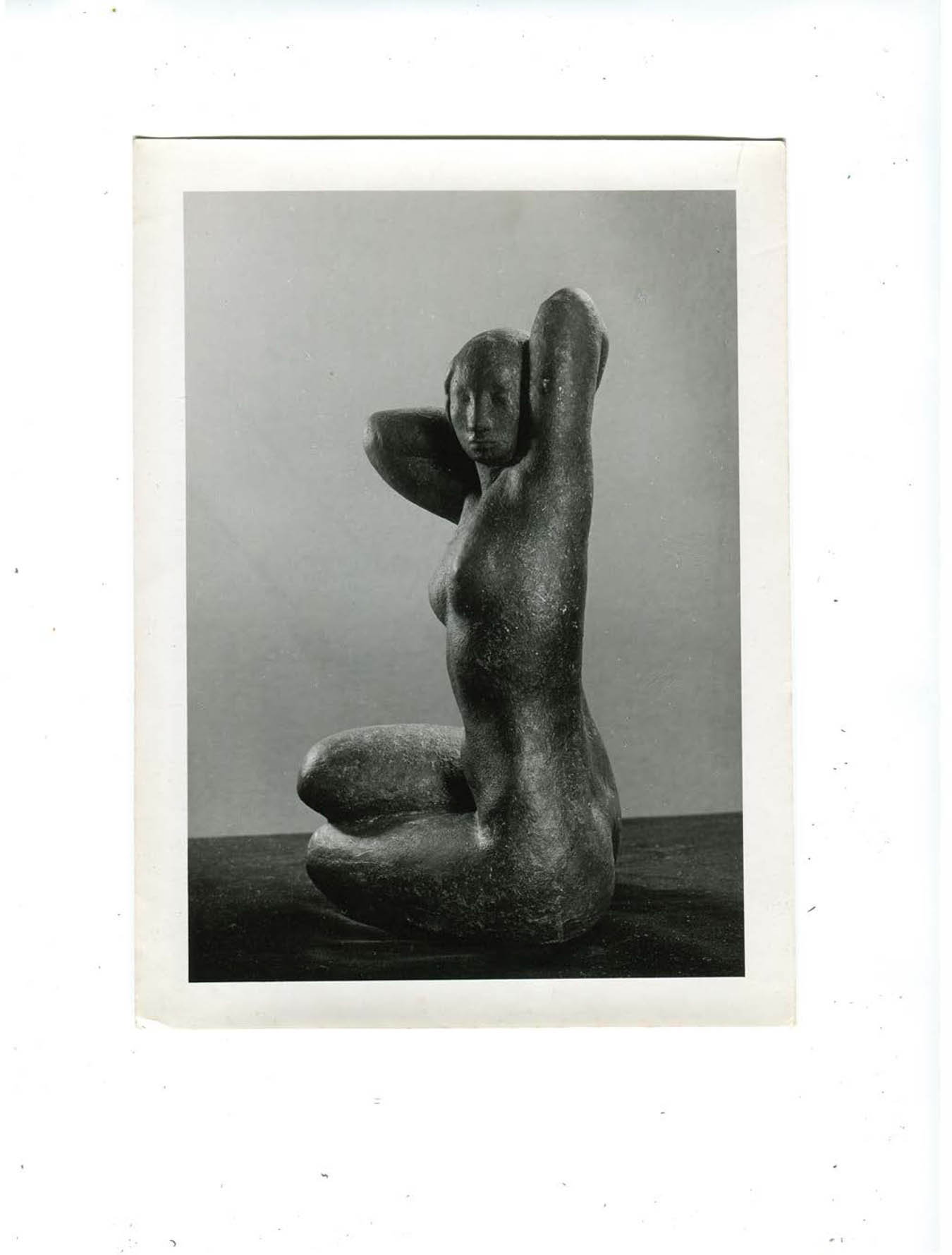

The artist’s sculpture was likewise heir to Weimar Expressionism. During the fascist period, Schottmüller’s sculpture was positively reviewed, and her bronze Dancer was reproduced in the Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung in 1941 (Figure 4.2).16

Figure 4.2: Oda Schottmüller, Studie zu einer Gartenskulptur (Study for a Garden Sculpture), undated (c. 1941). Plaster, whereabouts unknown. © Archiv Susanne und Dieter Kahl, Berlin.

In 1940, a reviewer named Nohara wrote highly of Schottmüller’s dual talent in both dance and sculpture which enabled her to “modulate the body and, vice versa, shape her sculpture according to living rhythms and impulses.”17 Only a few weeks before her arrest, a full-page spread in the women’s magazine Die junge Dame (The Young Lady) was full of praise and noted that the artist had gone on a tour of the army “to delight our field-grey soldiers … with her art.”18 Dancer represents a hybrid between a muted classicism and a remnant of an Expressionist idiom. It shows a female nude, seated with legs bent and tucked behind her, her torso twisted, arms angled at the elbow and bent behind shoulders and head, and an oval face with what appear to be closed eyes and chiseled features. The limbs are rounded; the surface of the material, probably plaster, roughened with punch marks. The sculpture does not conform to the stylistic mode of Cauer or Arno Breker but nor is it overtly avant-garde. Formally, it shows what was acceptable even within National Socialism. The positive press reception suggests that it was not Schottmüller’s art that ran counter to the authorities. It was her alleged political activity.

The police records of Schottmüller’s interrogations after her arrest do not survive. All we have are letters from prison, and it is to be doubted if Schottmüller expressed herself frankly in them. Schottmüller claimed not to have known half of the people she was accused of consorting with, nor to have known that the rest were communists, and not to have been aware of illegal broadcasts. In a letter to her father she wrote: “I was so glad that my stupidity + cluelessness about political things was proof enough that I could not have qualified for luring other people in or anything like that.… I’m entirely unaware of these things.”19 Even if Schottmüller herself may or may not have participated in counter-regime activities, she was certainly associated with people who did.20 She was part of the Berlin bohemian circle around the playwright and film critic Libertas Schulze-Boysen and her husband Harro Schulze-Boysen, a circle that also included, among others, photographer Elisabeth Schumacher; her husband, the sculptor Kurt Schumacher; clerical worker Hilde Coppi and her husband, industrial worker and former member of Weimar communist groups, Hans Coppi. The Schulze-Boysen circle was associated with espionage activities: Harro Schulze-Boysen was part of Hermann Göring’s intelligence staff at the Air Force Ministry and used his position to send secret documents and photographs to Soviet contacts while Hans Coppi broadcast messages in Morse code to Moscow.21 The National Socialist secret police coined the code name “Rote Kapelle” (“Red Orchestra”) for this and other communist groups.22 After 1945, these groups were largely ignored in the West as their links with the Soviet Union were seen as problematic in the Cold War climate; as a result, the “Red Orchestra” groups have only recently even been identified as resistance groups by scholars outside of the former Eastern bloc.23

In Schottmüller’s case, resistance led to death but Schottmüller’s art seems to have played no role in her arrest. This invites the question why she should be included in a discussion of artists and political resistance. One could argue that for Schottmüller it was almost incidental that she was a sculptor. It was, however, relevant that she was part of a politically resistant bohemian circle of artists and cultural producers. We may speculate to what extent she saw her art as an extension of her possible political affiliations, and how her aesthetic choices flew under the radar of official sanction, so to speak. She did not exhibit her work in any of the Great German Art Exhibitions and was, perhaps, not so easily categorized with her eccentric combination of dance, masks, and sculpture. Whether her art was read as subversive by audiences, whether the artist herself saw it as an effective tool of resistance to mainstream norms, or whether she regarded it as an escape from political reality, we may never know.

Hanna Cauer is an example of a sculptor who collaborated with National Socialism and whose aesthetics made it easy to do this. She would therefore seem to be a prime case study in what it meant not to resist. Cauer (1902–89) was thirty years old when the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) seized power. In a letter of April 20, 1933 to the newly appointed National Socialist minister of culture, Bernhard Rust, Cauer blamed the Weimar Republic for what she claimed was her lack of professional success to date, aligning her language with the public discourse of the new regime: “After my return to Germany [in 1930, after a sojourn abroad] I could not get a foothold anywhere because the reigning Jewish-Marxist circles were absolutely hostile to my German approach to art. Therefore I now appeal with renewed hopes to our national government, firmly trusting that I will find the necessary appreciation and support.”24 Cauer’s claim that she could not get a foothold was somewhat disingenuous as she had in 1930 been awarded the Rome Prize, administered by the Prussian Academy of Arts and the Prussian Ministry of Culture; she had, as she mentioned in her letter, only recently returned from the associated sojourn at the Villa Massimo in Rome.25 The “appreciation and support” that Cauer sought in her 1933 letter was the provision of studio space free of charge at the Berlin United State Schools of Fine and Applied Arts which that school’s director Max Kutschmann had refused her. A handwritten comment scribbled onto the letter by National Socialist state secretary Hans Hinkel shows the extent of official support for Cauer: “Kutschmann! Hanna Cauer must be provided for! Dr. Frick once again requests this.”26 As art historian Magdalena Bushart notes, Cauer had been told that there was no room in the school, but Wilhelm Frick, National Socialist minister of the interior, lobbied actively in order to secure a studio for her.27

The references to “Jewish-Marxist circles” and to her own “German art” were a tactical move, designed to appeal to the new political authorities. The amalgam “Jewish-Marxist” did not necessarily refer to the entire nexus of what we now understand as the racial ideology of the regime, an ideology that in 1933 did not yet (if it ever did) represent a stable and internally consistent program. In the context of cultural production, “Jewish-Marxist” was more likely to connote “avant-garde” or “anti-classical,” a reminder of how National Socialist racist discourses mapped onto other anti-modernist discourses dating back to the Wilhelmine era. Cauer’s own practice was mostly classical in orientation. The artist drew on a heritage of classical sculpture, part of a family tradition that reached back over four generations to the early nineteenth century.28 Her work was indebted to a particular form of classicism filtered through the nineteenth-century academy, a style in sculpture much in favor in Germany before the First World War. Cauer’s relatives had carried out numerous public commissions during the Wilhelmine empire. Her father Ludwig, for example, designed statues for Wilhelm II’s Siegesallee in Berlin between 1897 and 1900, and her uncle Emil the Younger designed the Siegfried fountain on the Rüdesheimer Platz in Berlin-Wilmersdorf around 1911.

In 1933, it was not yet clear that classicism was to be a favored style of the new National Socialist regime. Expressionism and folk art were equally posited as candidates for a revived national German art.29 Cauer putting forward her own classically inflected sculpture as a “German approach to art” was therefore, at this early date, a bit of a gamble; it was a gamble that paid off. By 1936, it had become evident that classicism was to be, if not the only, then certainly the most elevated of the styles to be associated with German sculpture under National Socialism.

Starting in the early years of the Hitler regime, Cauer received a string of public commissions, including two statues ordered by the city of Nuremberg for their opera house in 1934–5 (Allegretto and Moderato), and a fountain to mark the 1936 Olympic Games, placed in front of Berlin’s Red Town Hall.30 In 1936, Joseph Goebbels, Reich minister for propaganda, praised the Olympia fountain as “wonderful.”31 In the following year, Goebbels noted in his diary: “Hanna Cauer has created some magnificent sculptures of female figures. She is very capable. I’m giving her a whole string of commissions. The Führer, too, who joined us a little later, is giving her commissions and financial advances. She is completely happy.”32

Cauer received a lump sum of five thousand Reichsmark from Hitler in 1937.33 Between 1938 and 1940, her works were displayed in Gallery Two of the House of German Art at the Great German Art Exhibition in Munich; this was one of the galleries that flanked the central Hall of Honor, and it was reserved for the most prestigious sculptors of Germany.34 Most other sculptures were exhibited upstairs in the smaller galleries.35 One of the two Nuremberg figures, Allegretto, was awarded a gold medal at the Paris World’s Exposition in 1937, and subsequently placed in Gallery Fifteen of the House of German Art; in this gallery, Allegretto and Arno Breker’s Decathlete (commissioned for the Reich Sports Field at the Olympic Games) flanked Heinrich Zügler’s painting of sheep going out to pasture.36 Breker was to go on to become the most state-honored artist of the late 1930s and early 1940s, and one of Zügler’s paintings was purchased by Hitler in 1939. These commissions, placements, and personal commendations all show Cauer to have been favored by official authorities at the highest level throughout the fascist period.

Cauer’s academic style not only fitted in well with the monumental tasks and (from the mid–1930s) the classical formal language promoted by National Socialism; it also actively shaped that language. The two bronze figures of Allegretto and Moderato were placed in niches on either side of the Führer’s box at the Nuremberg Opera (Figure 4.3 and 4.4).37

Bushart points out that the life-size female nudes were shown without attributes but evoke a narrative by way of their mannered gestural language. Bushart suggests that Cauer in fact pioneered these “gestures, emptied of meaning,” which were later taken up by Breker in his sculptures for the new Reich Chancellery.38 The wrists of Cauer’s Allegretto bend at right angles to the arms, with the fingers of the hands held languidly, thumb curled into the palm. The curved hands and arms could be taken to signify “grace”; taken together, the two statues stand for art in a feminine mode. In an appraisal published in 1936, art historian Artur Kreiner praised Cauer as an artist who had enabled the Hellenic tradition in sculpture to evolve under Germanic auspices.39 He wrote of the Nuremberg statues: “Both of them softly elated and entirely balanced, they shape different emotions in similar measure. The lifted hand of Allegretto has the effect of a request, while the Moderato curbs with both hands.”40 A similar form of hand and finger shape can be detected in other sculptures of female figures in the late 1930s and early 1940s, very different to the angular hand-and-arm formations found in Expressionist sculptures of the 1910s and 1920s.41 Cauer’s sculptures, like other classical works of the 1930s, are not dynamic in character, and they do not reach out into space but rest in themselves, embodying a kind of Winckelmannian idealism of calm innocence. In this calm demeanor it is left to the hands, nay the fingers, to perform any affective address. Art historian Max Imdahl critiqued the poses and gestures of nude fascist statues for propagating the loss of individual freedom under National Socialism.42 Arguably, however, the loosely held hands and quasi-boneless arms also came to signify “art” itself; these gestures are what animate these figures and soften the effect of what feminist art historian Silke Wenk has called “erect female bodies.”43 Contemporary critics were clear that this was art’s function: not to communicate political ideologies in any overt way but to embody the German nation’s “soul” and thereby also to transport the viewer’s “soul.”44 This is how I read Cauer’s contribution to an incipient official language of sculptural classicism.

Figure 4.3: Hanna Cauer, Allegretto, 1935–6. Bronze, whereabouts unknown © Bildstelle und Fotoarchiv Stadt Nürnberg.

Figure 4.4: Hanna Cauer, Nischenfigur (Niche Figure, or Moderato), 1935–6, exhibited at the Great German Art Exhibition, 1937, in Gallery 15 [at right]. Plaster, dimensions unknown, location unknown © Stadtarchiv München, Fotosammlung; Photo: Georg Schödl, 1937.

It might seem appropriate to describe Cauer’s sculpture and career as conformist. Yet this characterization would miss the point in some ways, since it implies an effortful process of self-alignment with the agenda imposed by a regime. Cauer was not obliged to invest effort in processes of accommodation or negotiation. Her invocation of the classical fitted neatly with the recently hardened political line: until 1934, it had not been evident which style would prevail as truly expressive of “German” nationhood. In working to classicist expectations, Cauer remained true to her own tradition and stylistic preference, in the footsteps of her father, uncle, and grandfather. Her strategy was mostly one of exploitation: she worked to get the most out of her environment to support something she was already doing. Jonathan Petropoulos divides “artists under Hitler” into those who emerged from a modernist background in the 1920s to pursue accommodation, and those who realized accommodation to the regime.45 An artist like Cauer did not really have a modernist background. One could argue that she neither pursued nor realized “accommodation.” In that sense she resembled those artists analyzed by historian Alan Steinweis, whose work within the remit of regime policy was not based on tactical accommodation, but on a convergence of aesthetic, reputational, and economic interests.46 Cauer did not resist or accommodate fascist policies or aesthetic dicta. She is particularly interesting in view of the fact that it was not only sculptors such as Arno Breker and Josef Thorak with their hyper-masculine formal language who welcomed the chance to collaborate through art.

Milly Steger’s career is in many ways the most typical of the three artists discussed here in that she neither overtly resisted nor overtly collaborated. Steger is an example of a sculptor who “muddled through,” of someone who tried to continue her pre–1933 artistic practice and at the same time attempted to make the most of opportunities that presented themselves to her. Steger (1881–1948) was aged fifty-one when the NSDAP seized power in January 1933.47 Unlike Cauer and Schottmüller, Steger was in 1933 already an artist with an established career who was best known for her monumental architectural sculptures, commissioned for the Municipal Theater of the Westphalian city of Hagen in 1911. A number of further commissions in Hagen followed, including two figures for the Secondary School Altenhagen (1913), a bronze male blacksmith in the Volkspark (1914), and a set of colossal panthers for the Municipal Hall (1917).

Although Steger’s career began with public monuments, in the wake of the First World War and after her move to Berlin in 1917, public commissions dried up. The lack of state- and municipality-sponsored projects was partly a factor of the economic situation during the Weimar Republic, and partly a result of the changing architectural style for public buildings in the 1920s.48

After 1918, Steger’s work became smaller and more inward-turning. This may simply have been her response to the lack of large-scale commissions, though it may also have signaled an effort to address the chastened mood of a public traumatized by war, defeat, and political and economic instability. Her sculptures also started to look more Expressionist. Jephtha’s Daughter (1919, artificial stone) has an angular and semi-abstract design. Art critic Max Osborn analyzed it in formalist terms: “A game of effect and counter-effect, of harmonies and dissonances of line, practiced with a high degree of artistic maturity …”49 Other creative and critical practitioners also positioned Steger within the cutting-edge avant-garde, if not within Expressionism itself.

Steger herself remained committed to the idea of large-scale public sculpture and welcomed the renewed attention paid to monumental ensembles in fascist Germany. In a 1936 interview, Steger said:

Happily, we sculptors are in recent times once again and more and more invited to contribute by architects, and it is therefore the case that we can hope that we will soon experience once again the unified, great work of art, the work of art of our time, a harmonious combination of the three sister arts: architecture, painting and sculpture.50

Sculpture historian Birgit Schulte suggests that Steger’s hope for a renewal of some form of Gesamtkunstwerk is ironically reminiscent of the policies of the Arbeitsrat für Kunst, the Workers’ Council of Art, the socialist revolutionary group active between 1918 and 1921.51 The Council championed a fusion of all the visual arts under the umbrella of architecture. Steger was a founding member of the Worker’s Council, and in 1919, she contributed a text advocating equal rights for women in art education to the Council’s publication.52 Her later appeal to the new National Socialist state to realize the erstwhile utopian hopes of the socialist state of 1919 would reveal not so much a position of resistance but one of negotiation, turning a situation to advantage, and misprision of political purpose.

As it happens, during the National Socialist period, Steger did not receive the kind of large-scale, high-profile public commissions she had enjoyed before the Great War. However, the artist did receive official recognition on a smaller scale: in 1936, she was given a state commission for the statue of a stallion for the town of Insterburg in East Prussia, and she won awards for her entries to the Olympic Art Competitions of 1936 and 1940.53 Steger was also awarded the Rome Prize in 1938, the same award that Cauer had received eight years earlier.54 A figure for a fountain was illustrated in Die Kunst im Dritten Reich.55 In 1937, Steger joined two official National Socialist organizations, the Reich Chamber of Visual Arts and the German Women’s Welfare Organization (Deutsches Frauenwerk).56 Membership in these groups does not in and of itself indicate any degree of conformity, however, as it was very difficult to obtain art supplies or exhibition permits without such membership.57 In March 1934, Steger had asked the chair of the Reich Culture Chamber, state secretary Hans Hinkel, if Hitler would sit for a portrait bust for the German Lyceum Club in Berlin.58 It is unknown whether this bust was ever completed, but Steger’s initiative does at least demonstrate the artist’s endeavor to come to an arrangement with the new kinds of commissions on offer.

All of this would seem to indicate a career that was by and large negotiated around the exigencies of the new fascist state. Yet the overall picture is more equivocal. Steger’s work was not included in the touring exhibition of “Degenerate Art” that was opened in Munich in 1937, but eight of her works were confiscated as part of the associated project to “cleanse” the German “temples of art,” carried out on behalf of the Reich Ministry of Propaganda.59 The confiscated works were six drawings and prints, and two sculptures, Kneeling Woman (confiscated from the Municipal Museum in Hagen) and Walking Girl (taken from the National Gallery in Berlin).60 Given that Steger faced no discrimination elsewhere (as far as can be ascertained), it is difficult to reconstruct what it was about these sculptures in particular that elicited the label “degenerate.” Both sculptures were lost and believed destroyed until a fragment of the Kneeling Woman was recovered as part of the Berlin archaeological sculpture find of 2010 and dated to 1914/20 (Figure 4.5).61

The reclaimed fragment is too destroyed for us to be able to make any conclusive aesthetic judgment about it but it does seem to have been similar in style to some of Steger’s sculptures of the early 1920s, such as Female Half-Figure of 1920.62 That figure is executed using an attenuated, angular formal language, with legs cropped at the thigh and sharply defined abdominal muscles. Whether the choice of torso was deemed to violate the ideal of the “whole” human figure or whether it was an agonistic gestural idiom that contravened the calm classicism that had by 1937 become sculpturally acceptable, I can at this juncture only speculate. Adolf Ziegler, the head of the five-person commission that was tasked with choosing “degenerate” works to be removed from public collections said that the selection was to be made not on political but purely on artistic grounds; however, no specific guidelines as to the artistic criteria to be applied were issued.63

Figure 4.5: Milly Steger, Kniende (Kneeling Woman), cast stone, 32 in. / 81 cm high; fragment of Kniende as it was discovered as part of the Berliner Skulpturenfund of 2010. Property of the German Federal Republic © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte, Berlin; Photo: Achim Kleuker. .

In the very same year, and in seeming contradiction, Steger’s Musing Woman (plaster) was chosen for exhibition in the first Great German Art Exhibition of 1937 (Figure 4.6).64 Musing Woman was shown in Gallery Nine of the House of German Art, along a wall with five other unequivocally conformist works, including Richard Klein’s portrait bust of Hitler and Franz Bernhard’s high relief of two Hitler Youth boys. Christina Threuter suggests that Steger’s oeuvre presents a continuity of style from her time in Hagen to her death in 1948, with Expressionism only a short interlude in what was otherwise a “closed, voluminous design, reduced to its simplest form.”65 Amy Dickson, by contrast, argues that Steger’s practice was in dialogue with a classicized “Nazi aesthetic.”66 Stylistically, Musing Woman represents a departure from the Expressionist phase of Steger’s career. Whether this is a purely formal development within the artist’s oeuvre or an adoption of a more realistic style thought to be amenable to National Socialist ideological preferences, is difficult to say with any certainty. It is the case that during the 1930s classicism came to be privileged as a sculptural style in many Western countries of the globe, including the United Kingdom and the United States.67 This circumstance alone should sound a cautionary note against attempting to equate style with politics in a direct manner.

Figure 4.6: Milly Steger, Sinnende (Sitzende Figur) (Musing Woman [Seated Figure]), c. 1937. plaster, whereabouts unknown © Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München, Fotoarchiv Hoffmann; Photo: Heinrich Hoffmann, 1937.

It was unusual to have works exhibited in both the Great German Art Exhibition and the “Degenerate Art Exhibition” but Steger was not the only artist so situated. The sculptors Georg Kolbe and Rudolf Belling were also represented in both exhibitions. The regime was as polycratic in its cultural policy as it was in its economic, social and political endeavors. Much depended on regional and local micro-climates and the second- and third-tier party officials who wielded power within them. This may also explain Steger’s choice of Hitler for subject matter in her application for a commission in 1934. Within a regime marked by bitter in-fighting across many policy domains, Hitler was a “safe” choice of subject, unlikely to fall foul of local potentates who were themselves often locked in a struggle for power.

Within limitations, Steger found a way to work within the new framework of expectation. She was already a mature artist in 1933 and arguably accommodated her developing style to what promised success in terms of exhibition and commission opportunities. The inclusion of some of her works in the National Socialist art confiscation campaign did not imply a dissident art-political stance. Nor did it stigmatize her in the eyes of the authorities as an enemy of the regime and its policies. Artists whose work was confiscated and/or shown in the “Degenerate Art Exhibition” had not necessarily “resisted” in any way. Nearly all of the confiscated works had been produced before the National Socialist take-over in 1933, in a context where resistance meant something else entirely. Artists had no say in the matter of their work being confiscated or not; redress was not an option. Inclusion in the Great German Art Exhibition, on the other hand, was an active choice, and competition was stiff.68

In 2002, the American cultural critic and political agitator Stephen Duncombe proposed a sliding scale of understanding cultural resistance: cultural resistance as a free space, a launch pad for political activism, a rewriting of dominant discourse, an escape from politics and, finally, non-existent because the dominant system will ultimately exert hegemony over all cultural expression.69 An authoritarian regime like that of National Socialism was arguably one such hegemonic system that placed severe limits on the range and diversity of sculptural expression. Idealized classical figures, like those of Cauer, were tolerated within officially sanctioned channels; indeed, an artist like Cauer could be said to have exploited the system to her own advantage. On the other hand, hegemony was not absolute and cultural policies could be contingent, even muddled, as is suggested by the case of Steger’s works being both confiscated and exhibited. The regime responded with deadly swiftness to the suspicion of actual political resistance; the question of whether Schottmüller’s artistic practice was conformist or carved out a residually avant-garde niche within an authoritarian system was rendered irrelevant in the face of accusations of political subversion. Exploring the careers of three very different sculptors in fascist Germany has, I hoped, shed some light on the nuances that were possible even within the purview of dictatorship.

1Craig Clunas, “The Politics of Inscription in Modern Chinese Art,” Art History 41, no.1 (2018), 132–53. The literature on Heartfield is extensive; most recently: Sabine Kriebel, Revolutionary Beauty: The Radical Photomontages of John Heartfield (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014).

2Jost Hermand points out that National Socialist fascism could assert itself more extensively in sculpture than in painting because sculpture could adorn squares, sports stadia, ministry and other public buildings, and because of this potential placement in public spaces always had a social dimension. Jost Hermand, Kultur in finsteren Zeiten: Nazifaschismus, Innere Emigration, Exil (Cologne: Böhlau, 2010), 87–8.

3“Heroische Haltung, Härte und Disziplin haben die Seelen der Menschen empfänglicher denn je gemacht für monumentale Form und Inhalt. Unsere heutige monumentale Bildnerei hat ihre markantesten Vertreter in Arno Breker und Josef Thorak gefunden.” Ellen Schwarz-Semmelroth, “Kämpfendes Volk: Die 6. neue große Ausstellung im Haus der Deutschen Kunst in München,” NS.Frauen-Warte [sic]: Die einzige parteiamtliche Frauenzeitschrift 11, no.3 (1942), 34.

Semmelroth’s husband was SS–Hauptsturmführer Franz Paul Schwarz. On Semmelroth, see Laura Bensow, “‘Frauen und Mädchen, die Juden sind Euer Verderben!’ Eine Untersuchung antisemitischer NS-Propaganda unter Anwendung der Analysekategorie Geschlecht” (PhD diss., Leuphana Universität Lüneburg, 2016, and Hamburg: Marta Press, 2016), 118 n.435.

4James A. van Dyke, “Zur Geschichte der Staatlichen Kunstakademie Düsseldorf zwischen den Weltkriegen in Künstler im Nationalsozialismus: Die “Deutsche Kunst,” die Kunstpolitik und die Berliner Kunsthochschule, ed. Wolfgang Ruppert (Cologne, Weimar, Vienna: Böhlau Verlag, 2015), 156.

5“Dem Tafelbild ist ein Zimmer gemäß, der Skulptur der Platz. Im Zimmer wohnt der Einzelne, der Platz nimmt die Menge auf […] Die Plastik strahlt aus in einen Raum und kann dadurch viele Menschen beherrschen.” Hans Weigert, Geschichte der deutschen Kunst von der Vorzeit bis zur Gegenwart (1942), quoted in Entmachtung der Kunst: Architektur, Bildhauerei und ihre Institutionalisierung 1920 bis 1960, eds Magdalena Bushart, Bernd Nicolai and Wolfgang Schuster (Berlin: Frölich & Kaufmann, 1985), 105. On Weigert’s checkered career during the 1930s and 1940s, see Ruth Heftrig, “Neues Bauen als deutscher ‘Nationalstil’? Modernerezeption im ‘Dritten Reich’ am Beispiel des Prozesses gegen Hans Weigert, in Kunstgeschichte im Nationalsozialismus: Beiträge zur Geschichte einer Wissenschaft zwischen 1930 und 1950”, eds Nikola Doll, Christian Fuhrmeister and Michael H. Sprenger (Weimar: VDG, 2005), 119–37.

6On the integration of sculpture and architecture under National Socialism, see for example Alexander Heilmeyer, “Münchener Plastik,” Die Kunst im Dritten Reich 3, no.7 (1939), 203–13.

7“Ein unmittelbar und erfülltes Bild vom Menschen vermag von den bildenden Künsten am ehesten die Plastik zu formen. Sie bewahrt in unvergänglichem Stoff räumlich tastbar das Wesen des vergänglichen Seins. Das vom Bildhauer gestaltete Werk enthüllt die im Menschen wirkende Kraft des Lebens und hebt sein Einzeldasein in den großen Kreis der Schöpfung.” Johannes Sommer, Arno Breker, 2nd edn (Bonn: Ludwig Röhrscheid, 1943), 5. Sommer was professor for art history at the Hermann Göring-Meisterschule in Kronenburg; see Dieter Pesch and Martin Pesch, Werner Peiner— Verführer oder Verführter: Kunst des Dritten Reichs (Hamburg: disserta, 2014), 76.

8Anja Cherdron and Barbara Schrödl, “Frauen, Kunst und Karriere im Nationalsozialismus: Die Bildhauerin Hanna Cauer und der Spielfilm ‘Befreite Hände,’” in Deutsche Kunst 1933–1945 in Braunschweig—Kunst im Nationalsozialismus: Vorträge zur Ausstellung (1998–2000), ed. Erika Eschebach, (Braunschweig: Städtisches Museum Braunschweig, 2001), 183.

9In 1938, over 254 bronzes, 49 works in plaster and 12 in marble were shown. 183 works were heads, busts or animal sculptures. As regards medals and plaques, up to twelve or so works could be grouped into one catalogue entry; hence these figures are conservative. The quantities and percentages in the other Great German Art Exhibitions are comparable. I compiled these statistics from the entries and photographs available in the excellent database of the Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte, Munich, in associaton with Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin, and Haus der Kunst, Munich, “GDK Research: Grosse Deutsche Kunstausstellung 1937–1944,” 2011, http://www.gdk-research.de

10For commercial statistics, see Sabine Brantl, “Das Haus der Deutschen Kunst als Wirtschaftsunternehmen,” Haus der Kunst, Munich, lecture October 20, 2010, https://issuu.com/

11Frida Schottmüller was a specialist in quattrocento sculpture and assistant at the Kaiser Friedrich- Museum in Berlin. Hannelore Nützmann, “Ein Berufsleben: Frida Schottmüller,” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz, 40, no.1/2 (1996), 236–44.

12On the “Red Orchestra,” see Corina L. Petrescu, Against All Odds: Models of Subversive Spaces in National Socialist Germany (Oxford, Berne, Berlin, Frankfurt am Main, Vienna: Peter Lang, 2010), chapter 4, “The Anti-State Activism of the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack Organisation,” 169–240.

13“Beihilfe zur Vorbereitung eines hochverräterischen Unternehmens und zur Feindbegünstigung.” Quoted in Geertje Andresen, Die Tänzerin, Bildhauerin und Nazigegnerin Oda Schottmüller 1905–1943 (Berlin: Lukas Verlag, 2005), 276.

14“Ich halte Oda Schottmüller für eine Tänzerin von ungewöhnlich intensiver Erlebniskraft, das heißt Hingabefähigkeit an die innerlich erlebten Visionen, die sich ihr elementar und zwingend scheinen …” Quoted in Andresen, Die Tänzerin, 165–6.

15Andresen, Die Tänzerin, 167.

16Andresen, Die Tänzerin, 176, 180.

17“… sie kann den Körper modulieren, die Plastik wiederum nach lebendigen Rhythmen und Impulsen formen.” Nohara writing in Die Koralle, April 1940; quoted in Andresen, Die Tänzerin, 225.

18“… um unsere Feldgrauen […] mit ihrer Kunst zu erfreuen.” hz, “Mädchen hinter Masken: Oda Schottmüller ist Tänzerin und Bildhauerin zugleich,” Die junge Dame (July 28, 1942); reproduced in Andresen, Die Tänzerin, fig.134.

19“Ich war so froh, daß meine Dummheit + Ahnungslosigkeit über politische Dinge zur Genüge bewies, daß ich nicht dafür in Frage kommen könnte, meinerseits etwa andere Leute zu interessieren oder dergleichen […] ich bin ja darüber nicht so orientiert.” Quoted in Andresen, Die Tänzerin, 279.

20I thank Christopher Clark for this point.

21Shareen Blair Brysac, Resisting Hitler: Mildred Harnack and the Red Orchestra (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 235–9, 294–6. American translator and lecturer Mildred Harnack and her husband, the lawyer Arvid Harnack, were also associated with the Schulze-Boysen circle. All were executed in 1942–3.

22Anne Nelson, German Resistance to the Nazi State Red Orchestra: The Story of the Berlin Underground and the Circle of Friends Who Resisted Hitler (New York: Random House, 2009).

23Hans Mommsen, “The German Resistance against Hitler and the Restoration of Politics,” Journal of Modern History, 64 (December 1992), 112–27.

24“Nach meiner Rückkehr nach Deutschland […] konnte ich nirgends Fuß fassen, da die regierenden jüdisch-marxistischen Kreise meiner deutschen Kunstauffassung absolut ablehnend gegenüberstanden. Ich wende mich deswegen jetzt mit neuen Hoffnungen an unsere nationale Regierung mit dem festen Vertrauen, die nötige Anerkennung und Förderung zu finden.” Quoted in Magdalena Bushart, “Der Formsinn des Weibes: Bildhauerinnen in den zwanziger und dreissiger Jahren, in Profession ohne Tradition: 125 Jahre Verein der Berliner Künstlerinnen (Berlin: Berlinische Galerie, 1992), 149.

25Jobst C. Knigge, “Die Villa Massimo in Rom 1933–1943: Kampf um künstlerische Unabhängigkeit” (PhD diss., Humboldt-Universität Berlin, 2013), 11, http://edoc.hu-berlin.de/

26Letter May 5, 1933; quoted in Bushart, “Der Formsinn,” 149.

27Bushart, “Der Formsinn,” 149.

28For the Cauer dynasty of sculptors, see Anne Tesch, Die Bildhauerfamilie Cauer (Bad Kreuznach: Harrach, 1977); Elke Masa, “Die Bildhauerfamilie Cauer im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert: Neun Bildhauer aus vier Generationen—Emil Cauer d.Ä., Carl Cauer, Robert Cauer d.Ä., Robert Cauer d.J., Hugo Cauer, Ludwig Cauer, Emil Cauer d.J., Stanislaus Cauer, Hanna Cauer” (PhD diss., Free University Berlin, 1988, and Berlin: Gebrüder Mann, 1989). A brief overview is given in Peter Bloch, Sibylle Einholz and Jutta von Simson, eds, Ethos und Pathos: Die Berliner Bildhauerschule 1786–1914: Ausstellungskatalog (Berlin: Gebrüder Mann, 1990), 67–71. Cauer was the daughter and student of sculptor Ludwig Cauer, the niece of sculptor Emil Cauer the Younger, the grand-daughter of sculptor Carl Cauer and the great-grand-daughter of sculptor Emil Cauer the Elder. Interior minister Wilhelm Frick also supported Cauer’s father, Ludwig.

29Writing in Kunst der Nation in November 1933, art critic Gert H. Theunissen advocated a new creativity in the spirit of Expressionism. Kirsten Baumann, Wortgefechte: Völkische und nationalsozialistische Kunstkritik 1927–1939 (Weimar: VDG, 2002), 156–7. The völkisch art journal Das Bild, edited by Bettina Feistel-Rohmeder, never embraced classicism and pointedly illustrated only folk art or mediaevalizing works. See the journal itself and also Annette Ludwig, Die nationalsozialistische Kunstzeitschrift Das Bild: “Monatsschrift für das Deutsche Kunstschaffen in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart.” Ein Beitrag zur Verlagsgeschichte (Heidelberg: C.F. Müller, 1997). See also Jonathan Petropoulos, Artists under Hitler: Collaboration and Survival in Nazi Germany (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2014), and Eckhart Gillen, “Zackig … schmerzhaft … ehrlich …: Die Debatte um den Expressionismus als ‘deutscher Stil’ 1933/34,” in Ruppert, Künstler im Nationalsozialismus, 202–29.

30Other commissions included a bust of interior minister Wilhelm Frick for the Reichstag in 1933, a fountain for the city of Posen, a marble statue of Pallas Athena for the ministry of the interior in 1938–9, and another fountain for the Prussian ministry of culture. Bushart, “Der Formsinn,” 149.

31Joseph Goebbels, diary entry, July 29,1936; quoted in Bushart, “Der Formsinn,” 149.

32“Hanna Cauer hat herrliche Frauenplastiken geschaffen. Sie kann sehr viel. Ich gebe ihr eine ganze Reihe von Aufträgen. Auch der Führer, der etwas später noch hinzukommt, gibt ihr Aufträge und Vorschüsse. Sie ist ganz glücklich.” Goebbels, diary entry, December 17, 1937; quoted in Bushart, “Der Formsinn”, 149.

33Bushart, “Der Formsinn,” 149.

34See “GDK Research.”

35Bushart, “Der Formsinn,” 149.

36Zügler’s painting was titled Ausfahrt. Another of Zügler’s landscapes, Lüneburg Heath, was purchased by Hitler in 1939. Bushart notes that Cauer’s Allegretto was placed on an honor podium next to Adolf Ziegler’s Four Elements. Photographs show that Ziegler’s painting hung on the opposite wall to the Breker-Zügler-Cauer ensemble in Gallery 15, and that Breker’s and Cauer’s statues were placed on low plinths. There is no sign of a special podium in the photographs. See “GDK Research”; and Bushart, “Der Formsinn,” 149.

37Bushart, “Der Formsinn,” 149.

38Artur Kreiner, “Neue Bildhauerwerke im Nürnberger Opernhaus,” Kunst und Volk, 4, no.9 (1936), 318.

39Kreiner, “Neue Bildhauerwerke,” 318.

40“Beide sanft beschwingt und völlig ausgewogen, gestalten sie bei gleichem Maß verschiedene Empfindungen. Wirkt die erhobene Hand des ‘Allegretto’ wie eine Aufforderung, so dämpft ‘Moderato’ mit beiden Händen.” Kreiner, “Neue Bildhauerwerke,” 318. On Artur Kreiner, albeit glossing over the National Socialist period, see the obituary by Otto Barthel, Frankenland, (September 18, 1965), 302, http://frankenland.franconica.uni-wuerzburg.de/

41Languidly curved arms and fingers with loosely bent thumbs can be seen, for example, in the sculptures by Lore Friedrich-Gronau, Lotte Benter-Bogdanoff, Arno Breker, and Fritz Klimsch. Contrast the angular limbs of pre–1933 works by Emy Roeder, Milly Steger, Herbert Garbe, or Katharina Heise.

42Max Imdahl, “Pose und Indoktrination: Zu Werken der Plastik und Malerei im Dritten Reich”, in Nazi-Kunst ins Museum? ed. Klaus Staeck (Göttingen: Steidl, 1988), 87–99.

43Silke Wenk, “Aufgerichtete weibliche Körper: Zur allegorischen Skulpture im deutschen Faschismus”, in Inszenierung der Macht: Ästhetische Faszination im Faschismus (Berlin: Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst and Dirk Nishen Verlag, 1987), 116.

44See, for example, Sommer, Arno Breker; Georg Schorer, Deutsche Kunstbetrachtung (Munich: Deutscher Volksverlag, 1939), https://archive.org/

45Petropoulos, Artists under Hitler.

46Alan E. Steinweis, Art, Ideology, and Economics in Nazi Germany (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996). I thank Christopher Clark for this reference.

47On Steger’s career, see Carmen Stonge, “Women and the Folkwang: Ida Gerhardi, Milly Steger, and Maria Slavona,” Woman’s Art Journal, 15, no.1 (Summer 1994), 3–10; Birgit Schulte, “Von der Skandalkünstlerin zur Stadtbildhauerin: Milly Steger in Hagen,” in Die Grenzen des Frauseins aufheben: Die Bildhauerin Milly Steger 1881–1948, ed. Birgit Schulte with Erich Ranfft, (Hagen: Neuer Folkwang Verlag im Karl Ernst Osthaus-Museum, 1998), 33–44, http://www.keom02.de/

48On German architecture in this period, see the brilliant analysis by Barbara Miller Lane, Architecture and Politics in Germany 1918–1945 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985 [1968]).

49“Ein mit hoher künstlerischer Reife geübtes Spiel von Wirkungen und Gegenwirkungen, von Linienharmonien und -dissonanzen.” Max Osborn, “Berliner Sezessionsplastik,” Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, 45 (1919–1920), 293.

50“Erfreulicherweise werden wir Bildhauer in letzter Zeit wieder mehr von den Architekten zur Mitarbeit herangezogen, und so können wir hoffen, dass uns bald wieder das einige, große Kunstwerk erstehen wird, das Kunstwerk unserer Zeit, eine harmonische Verbindung der drei Schwesterkünste: Architektur, Malerei und Plastik.” Interview in Koralle, 4, no.5 (1936); quoted in Schulte, “Von der Skandalkünstlerin,” 14.

51Schulte, “Von der Skandalkünstlerin,” 14.

52Steger responded to a questionnaire sent out to all artist members. Arbeitsrat für Kunst, ed., Ja? Stimmen des Arbeitsrates für Kunst in Berlin (Berlin: Photographische Gesellschaft, 1919).

53Anita Beloubek-Hammer, “Die schönen Gestalten der besseren Zukunft”: Die Bildhauerkunst des Expressionismus und ihr geistiges Umfeld (Cologne: LETTER Stiftung, 2007), volume 2, 682.

54Beloubek-Hammer, “Die schönen Gestalten”, 682; Knigge, “Die Villa Massimo.”

55Bushart, “Der Formsinn,” 140.

56Amy Dickson, “Biology, Body and Sculpture: Milly Steger and Emy Roeder in the 1930s” (MA diss., Courtauld Institute of Art, 2003), 28.

57I thank Elizabeth Otto for this point.

58Beloubek-Hammer, “Die schönen Gestalten,” 682.

59On the Kunsttempelsäuberungsaktion, see Peter-Klaus Schuster, ed., Die “Kunststadt” München 1937: Nationalsozialismus und “Entartete Kunst” (Munich: Prestel, 1987).

60See the excellent database assembled by the Freie Universität Berlin, Datenbank zum Beschlagnahmeinventar der Aktion “Entartete Kunst,” Forschungsstelle “Entartete Kunst,” Fachbereich Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaften, Freie Universität Berlin, “Datenbank ‘Entartete Kunst,’” 2010, http://www.geschkult.fu-berlin.de/

61Birgit Schulte identified the recovered fragment with 98% certainty as Steger’s lost Kneeling Woman. Birgit Schulte, “Milly Steger, Kniende, um 1914/20”, in Der Berliner Skulpturenfund: ‘Entartete Kunst’ im Bombenschutt. Entdeckung—Deutung—Perspektive, eds Matthias Wemhoff, Meike Hoffmann and Dieter Scholz (Berlin: Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte, and Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner, 2012), 113–22. Walking Girl is possibly the stone Schreitendes Mädchen, illustrated in Westermanns Monatshefte 56, no.112, part 2 (1912).

62Whereabouts unknown; illustrated in Birgit Schulte with Erich Ranfft, eds, Die Grenzen des Frauseins aufheben: Die Bildhauerin Milly Steger (Hagen: Neuer Folkwang Verlag im Karl Ernst Osthaus-Museum, 1998).

63Mario-Andreas von Lüttichau, “‘Deutsche Kunst’ und ‘Entartete Kunst’: Die Münchner Ausstellungen 1937,” in Schuster, Die “Kunststadt,” 97.

64“GDK Research.” The catalogue mistakenly listed the artist as “Willy” Steger.

65Christina Threuter, “Die begehrten Körper der Bildhauerin Milly Steger”, in Gender-Perspektiven: interdisziplinär—transversal—aktuell, ed. Christel Baltes-Löhr and Karl Hölz (Berne, Berlin, Frankfurt am Main, Vienna: Peter Lang, 2004), 94.

66Dickson, “Biology, Body,” 28.

67Martin Damus,“Plastik vor und nach 1945: Kontinuität oder Bruch in der skulpturalen Auffassung,” in Bushart, Nicolai and Schuster, Entmachtung der Kunst, 119–40.

68In 1937, there were fifteen thousand submissions, and around one thousand five hundred or 10% were chosen by the jury for exhibition to the Great German Art Exhibition. Lüttichau, “‘Deutsche Kunst’,” 87.

69Stephen Duncombe, ed., Cultural Resistance Reader (London: Verson, 2002), 5–8. I thank Deborah Ascher Barnstone for this reference.