Jennifer Kapczynski

In September 1932, avant-garde artist and filmmaker Ella Bergmann-Michel took up her movie camera with the intention of gathering footage for a new documentary short. Wahlkampf 1932 (Election Campaign 1932) was supposed to capture the public climate in the lead up to the national vote, during what turned out to be the last months of Germany’s young democracy. It was a project Bergmann-Michel never completed, and one that came to epitomize the interrupted arc of Weimar leftist filmmaking in the fateful period of transition from democracy to totalitarianism. Recording political interactions on the streets of Frankfurt am Main, Bergmann-Michel documented the deadlocked character of public debate in the final days of the Weimar Republic. Her work was cut short, however, when she filmed a fistfight that took place in front of a polling station. For her actions Bergmann-Michel was arrested and briefly detained, and the police seized her camera and ruined her footage by exposing the 35mm cassette.1 Although Bergmann-Michel later declared that she ceased filming in January 1933 (that is, coinciding with Hitler’s takeover),2 my research indicates that she must have continued filming until some time after March 1933. This slight shift in timeline might be insignificant in another period, but not at a time of such rapid and drastic political change. My findings show that the film is not only, as has been commonly assumed, a final, portentous look at the collapse of the Weimar Republic, but also a bridge text that connects the moments before and after the National Socialist rise to power. This revised chronology opens up ways of thinking about how Bergmann-Michel’s film engages with the role of art in resistance, giving the film new meaning as a work that looks both backwards and ahead—like Walter Benjamin’s Angel of History, transfixed by the wreckage behind it and yet propelled forward into the future.3

Bergmann-Michel’s movie camera was returned to her following her release from custody, and she eventually edited what remaining material she possessed to create a dialectical reflection on the end of Germany’s first democratic republic. Although it is not clear just when she did the editing, the film was not screened publicly until 2012 (well after Bergmann-Michel’s death in 1971), and it remains classified as an unfinished work. With hindsight, Bergmann-Michel gave the thirteen-minute film a mournful new name: in place of Wahlkampf 1932, she titled it Letzte Wahl, meaning “Final Vote” but also “Last Choice.” It would, in fact, be her final film—a parting shot in the most literal sense. In the face of increasing authoritarianism and with an all-too-intimate awareness of the dangers faced by those agitating against the National Socialists, Bergmann-Michel probes the possibility that critical viewing practices might constitute a final avenue for resistance, offering up her film as an illustrative example. Encouraging viewers to watch reflectively, Bergmann-Michel prompts the audience to practice the art of “reading between the lines” as a means to create a counterdiscourse, i.e., a countervailing way of looking and thinking that might support critique and even change. At the same time, the film has a mournful, even mute quality in certain moments that seems to query whether art has any remaining room to maneuver. Shot not only before, but also after the Nazi takeover, the film captures a moment in time when the space for safe resistance was disappearing at a terrifying speed, and when prospects for a politically progressive artistic practice were never more bleak.

Bergmann-Michel spent most of the Second World War living in full retreat from public life at the “Schmelz,” a former paint factory in the rural outskirts of Frankfurt am Main (in Vockenhausen am Taunus) that had been inherited by her husband, fellow artist Robert Michel. There, the two had created a kind of artist colony in the 1920s (nicknamed by Robert “The Heimat Museum of Modern Art”),4 where they could engage in their own practices and also host frequent visits by friends, including many of the leading figures of the Weimar art scene: Willy Baumeister, László Moholy-Nagy, Ilse Bing, Jan Tschichold, Dziga Vertov, and Kurt Schwitters.5 After the National Socialist takeover, Robert established a fish farming business on the property, which he maintained into the postwar period. For a time, Ella managed to continue with her commercial artwork (work she devalued, but that provided useful income), spending two months a year in a London atelier between 1937–9 until the start of war made that impossible.6 She spent the remaining years at the Schmelz engaged in farming and raising livestock, while also continuing to produce some art (mainly drawing).7 A bomb that struck Bergmann-Michel’s childhood home in 1945 in Paderborn destroyed much of the couple’s early works.

In the postwar period, Bergmann-Michel began showing her graphic work once again, but she dedicated even more energy to promoting the revival of avant-garde film culture. She founded the “Film-Studio” (later renamed “Film-Club Frankfurt”), personally introducing or lecturing at most screenings, and later helped found the Kronsberg youth film club (near Hanover). In addition, she authored a lecture series on “50 Years of International Film,” which she brought to America House locations in Frankfurt, Heidelberg, and Marburg, and gave numerous talks on art-historical topics.8 Despite this intense engagement with cinema, Bergmann-Michel never seems to have resumed her own filmmaking endeavors. This was not for lack of desire, it appears. As she noted forcefully in a letter to close friend and art historian Hans Hildebrandt (employing playfully idiosyncratic spelling):

Auch ich habe Film-Ideen—ich ich—nicht Michel—vorläufig—aber die kann ich nicht aufs Papier spuckkken, da sie erst spuuuken und nur spuckkken wenn du hier neben mir sitzt, und dafür warte ich auf die Telefon-Klingel.

(I, too, have ideas for films—I, I, not [Robert] Michel—for the time being—but I can’t spittt them onto paper, since they initially just hauuunt me and only spittt forth when you sit here beside me, and for that reason I am waiting for your phone call.)9

In stuttering prose (almost as if to mimic a jammed projector), Bergmann-Michel voices not only her stalled cinematic vision, but also a certain frustration that her ambitions might be confused with those of her husband—understandable, since only she had ever undertaken any film work, and yet the two tended to be viewed as a collective entity.

Until the accidental discovery in 1982 of numerous reels of her work, uncovered after a West German television station decided to clean house, most of Bergmann-Michel’s films were effectively lost.10 As it stands, her film work has gone almost entirely unnoticed by scholars, despite the relative rarity of avant-garde women filmmakers of the Weimar era, and the fact that Edition Filmmuseum released a DVD of the director’s documentary films in 2006. There are a couple of notable exceptions: an overview piece by Jutta Hercher and Maria Hemmleb, published in 1990 in Frauen und Film, and, from 2017, an incisive article by Megan Luke on “Collective Homemaking in the Films of Ella Bergmann-Michel.” There has been more attention to Bergmann-Michel’s collage and drawing work, which is represented in a number of major museum collections, but even that is relatively scant and exists mostly in catalog form. As yet no published work treats Letzte Wahl in any detail.

Bergmann-Michel took a fluid approach to her own art, which may explain partially why her work has garnered relatively little scholarly interest, or the fact that from the beginning, her work was paired with that of her husband. Treated both in their lifetimes and after death as a “Künstlerpaar” or “artist couple,” Robert and Ella frequently exhibited as a team, and although more recent work has begun to recognize her particular contributions, it seems indicative that even their archive is jointly named: the Getty Museum’s partial collection is named the “Papers of Ella Bergmann-Michel and Robert Michel.” Ella Bergmann and Robert Michel first met in the avant-garde art hub of Weimar, where she had gone to study art (although the independent-minded Ella soon chafed at the culture of the academy and quit in 1918.)11 After the Bauhaus established itself in the city, the couple enjoyed an initially friendly relationship with the movement, with Walter Gropius even borrowing examples of their artwork in order to showcase pathbreaking practices on the walls of the newly opened school.12 Although the precise reasons for the couple’s departure from Weimar and break with Bauhaus are somewhat unclear, Jutta Hercher suggests that it was Robert who pushed for the move after growing frustrated with the movement’s dogmatism.13 The pair relocated to the Frankfurt area in 1920 and by mid-decade had joined the neue frankfurt movement, which was heavily engaged in promoting progressive architecture and art in the reformation of urban life, and where Bergmann-Michel, as a co-founder of the “Arbeitsgemeinschaft für neuen Film/Liga für unabhängigen Film” (Working Collective for New Film/League for Independent Film), began her first serious engagement with film.14 Much of Bergmann-Michel’s photographic and film work reflects the broader concerns of the movement. As a photographer, she often worked serially, as Luke describes, in order “to visualize patterns of tonal contrast and, above all, movement,” and she used photo series as preliminary studies for her films.15 In both media, Bergmann-Michel explored how architecture shaped daily life, from her photo series “Frankfurter Siedlungen” to her first film, Wo wohnen alte Leute (1932), which contrasted traditional with progressive housing for the elderly and was intended to “articulate a ‘social demand’ and make an argument for a reconsideration of housing more generally.”16 It was part and parcel of what Luke describes as a concern with the “quality of community in the modern city.”17 In Letzte Wahl, too, the director seeks to probe this quality of community, if on a rather different axis. As I argue in what follows, Bergmann-Michel uses the documentary form to examine the state of public discourse—not only the interplay of written text and image, but also the conversational dead ends of 1932/33, the literal word on the street. At the very moment when German commercial filmmaking truly and finally converted to sound and Weimar democracy was taking its last breaths, Ella Bergmann-Michel crafts a silent film about speech.

Consider the dynamic that unfolds in just the film’s first half minute. Bergmann-Michel opens her film at eye level, with a long shot approximately ten seconds in duration. A tilt pan of a city streetscape slowly swings upward to reveal a small vista in the Frankfurt Altstadt. From almost every window hangs a flag—for the most part, bearing either the KPD’s familiar hammer and sickle or the triple thrusting arrows of the SPD. There is an airless quality to the footage: the ubiquitous flags flap softly in the breeze, and the pace of Bergmann-Michel’s camerawork is tempered, steady. At the same time, the warring symbols signal from the film’s opening moments to a city embroiled in divisive political battle. Bergmann-Michel evokes a basic puzzle that will shape the remainder of her thirteen-minute film, between stasis and conflict, between warring words and lack of movement. The feeling is one of entrenched and irreconcilable oppositions.

Cut to a medium shot of a Litfaßsäule (an advertising column commonly found in German public spaces) plastered with political posters. Framed at an extreme canted angle, the column thrusts sharply toward the right of the frame, resembling a megaphone or even the mouth of a cannon, as if positioned to launch forth a volley of propaganda. The posters adorning the column are extremely text-heavy and, at this remove, mostly indecipherable except for their large graphics, which call upon voters to support this or that list—all with the urgency of the imperative: Wählt 8! 1! 4! (Figure 6.1). What follows are three shots that move ever closer toward the textual display: first, a canted close-up of a poster for Liste 4-Zentrum, its lettering partially obscured by Bergmann-Michel’s framing, now tilted to the left as if to mirror in reverse the trajectory of the leaning column in the preceding shot (Figure 6.2). As with Bergmann-Michel’s earlier architectural work, we find a play here between the abstract and concrete, surface and depth. As viewers, we attempt to piece together the text, but the truncation of word and image draws our attention to the graphic tonalities of the composition as much as its communicative function.18 At the same time, the camera’s proximity to its subject reveals a series of wrinkles and small air bubbles underneath the paper, a reminder of the poster’s materiality. Cut still closer, as segments of text from yet another advertisement shimmer before our eyes, the slight shaking of Bergmann-Michel’s handheld Kinamo camera is palpable. Although this shot is now level rather than canted, the extreme close-up eliminates the larger framework for the poster’s words, which swim to the surface randomly as our eyes scan and attempt to make meaning from them: Großherzogin, Mecklenburg, 100,000RM, 185,000RM (“archduchess, Mecklenburg, 100,000 Reichsmark, 185,000 Reichsmark”). Cut, and the camera zeroes in on a new set of words: Kriegerwaise, letzte Not, keinen Pfennig, Unterschenkel (“war orphan, emergency, not a penny, lower leg”). As viewers, we can imagine the thread of a dialogue about war and class inequities, but we never learn just how or for what purpose this curious assemblage of words comes together. Instead, cut to a medium shot of the top of the column, slanting sharply leftwards and now revealing the upper half of the Zentrum poster. Center Party candidate Heinrich Brüning (and chancellor of Germany from March 1930 to May 1932) gazes down sternly; bordering him to the right, on a separate poster, is a faceless uniformed officer of the Sicherheitsdienst. And then comes the first image confirming, front and center, what, at least as contemporary viewers, we know must be there among the propaganda images: a head-on shot of a swastika-emblazoned campaign poster for the Nazi Party, followed almost immediately by a visual rebuttal—an appeal (by which party, we cannot yet tell) to all women and children decrying the “Gefühlsrohheit der Nazis,” the “Nazis’ emotional brutality.”

Figure 6.1: Ella Bergmann-Michel, Wahlkampf 1932 (Letzte Wahl), 1932 (Figures 6.1–6.2 and 6.4–6.8). A Litfaßsäule plastered with campaign posters vies for voters ahead of the November 1932 national vote. Screenshot.

Figure 6.2: A close-up of a poster for the Center Party list for the November 1932 elections. Screenshot.

As the camerawork, framing and editing of Letzte Wahl pull us backwards and forwards, side to side, Bergmann-Michel draws the viewer into a discursive maelstrom characterized by intense yet strikingly amorphous oppositions. Barraged by text and images stripped of their full setting, the spectator struggles to make sense of their interrelationship—forced to fill in the blanks, either from memory or via the imagination, and at the same time made acutely aware through the film’s provocative juxtapositions that a profound struggle underlies these warring words. In essence, Bergmann-Michel’s cinematography and editing conjure a sense of “shouting,” of visual and verbal volleys grown to such a crescendo that clear communication and conversation have become impossible—a literal form of Papierkrieg. She evinces a world of political non-sense, cleverly highlighting the very breakdown of dialogue by deploying the principles of dialectical montage (a style of editing that uses contrasting images in order to generate provocative associations, employed most famously by Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein in works such as Strike [1925]). Letzte Wahl is a silent work, and the film relies entirely on the relationship between images to generate its sense of discordance. The film evokes a striking duality: like the opening image of the city’s languidly waving flags, we find a tension here between the film’s visual clash and its acoustic stillness, giving rise to an image of Frankfurt as both riven by conflict and at the same time stifling, as if lacking the air for real debate.

In this respect, Bergmann-Michel’s preoccupation with the space of and around the Littfaßsäule cannot be coincidental. Not only were the columns a key site for political advertising and public engagement—a world with which Ella Bergmann-Michel was well acquainted through her own and Robert’s commercial work—and as such constituted an obvious location on which to train her camera, they also featured prominently in one of the most sensational feature films of the Weimar era: Fritz Lang’s M, released the year before Bergmann made her study.19 As a director with a general interest in avant-garde work, Bergmann-Michel certainly would have known Lang’s film, which drew on the case of a notorious child murderer to explore, on the one hand, the breakdown of civil discourse in communities in crisis, and on the other hand, the rise of authoritarianism. In the fictional work, the Littfaßsäule serves to disseminate information about the search for the serial killer, but it also becomes a crime scene in and of itself: the murderer lures his child victim while standing in front of a poster announcing a hefty reward for tips leading to his capture (Figure 6.3). The Littfaßsäule, linked to a sensationalizing press that publicizes the murders in “extra editions” in order to maximize the amount of copy sold, becomes another instrument in a media network fomenting collective hysteria and suspicion in the general public while yielding little of value for the investigation. Notably, in Lang’s film, sound rather than image provides the critical clue that leads to the apprehension of the suspect. Lang—and like him, Bergmann-Michel—reflects on both the disseminative power of the printed word and its limits. Echoing Lang’s earlier work, Bergmann-Michel suggests that the Littfaßsäule leads to more social discord than communication, and points toward the manner in which the general excess of media messaging around the election has contributed to the breakdown of public discourse.

Figure 6.3: On a Berlin Litfaßsäule, the profile of the murderer in Fritz Lang’s M (1931) casts a shadow on the wanted poster describing his own crimes. Screenshot.

Strikingly, Letzte Wahl does not exploit the camera’s exceptional capacity for rendering mobility (in contrast to Bergmann-Michel’s other films, such as Fliegende Händler in Frankfurt am Main of the same year, or to the astonishing dynamism found in Joris Ivens’s De Brug, Arnold Fanck’s mountain films, or Walter Ruttmann’s Sinfonie der Großstadt—all of which were made with the same type of Kinamo camera that Bergmann-Michel employed).20 Indeed, although Bergmann-Michel creates a clear sense of rhythm with her editing, her emphasis on static shots seems deliberate—a gesture intended to communicate the political blockages of 1932/33 at the level of film form. There is a sense of clash but little movement, except for one notable moment of aerial footage showing the snaking lines of brownshirts marching through the city (apparently shot from the window of the director’s centrally located atelier).21 Instead, through her focus on the materials of advertising, Bergmann-Michel presents an image of political debate now literally fixed in place.

As the film wends on, we find the senseless shouting effect of this opening segment echoed in numerous shots of actual public debate. Bergmann-Michel observes as pedestrians mill about, stopping to read the ubiquitous political posters and to confront one another with wagging fingers. In part, this reflects the extent to which Letzte Wahl is an exploration of community—a point of continuity, as mentioned before, with Bergmann-Michel’s earlier films, although here we remain confined to its forms as engendered in the narrow spaces of the city center, with no glimmer of architectural progressivism. Bergmann-Michel is not simply an observer of this community, though. Indeed, Bergmann-Michel herself stands at the heart of the film, as she repeatedly elicits curious and sometimes angry stares from her subjects. This was partly a feature of her equipment: the Kinamo was remarkably compact and spring-loaded, which meant it could be operated without a tripod, a veritable extension of the body behind the lens. (After his own first experiments with the camera, Joris Ivens raved “that the camera was an eye,” and declared “if it is a gaze, it ought to be a living one.”)22 As a rare female filmmaker, Bergmann-Michel would have drawn particular attention as she captured Frankfurt street life, especially in such a politically volatile time. Indeed, even though Bergman-Michel adopts mostly static shots, there is—as I mentioned earlier—a slight vibration to her camerawork that, coupled with so many shots of subjects looking back, conjures in the film a sense of immediacy and intimacy, vulnerability, even (Figure 6.4 and 6.5). As an archival document concerning one of her earlier works makes clear, the dangers she faced were quite real. In a memo from April 6, 1932 detailing a call with a certain Dr. Frey concerning Bergman-Michel’s request to film in the courtyard of the unemployment office for her documentary Erwerbslose kochen für Erwerbslose (Unemployed Cook for the Unemployed, 1932), it was noted that “Zusicherungen, dass Frau Bergmann-Michel durch die Arbeitslosen unbehelligt bleibt, können nicht gemacht werden. Es sei vorgekommen, dass die Arbeitslosen den Filmoperateur bedroht hätten und ihm beinahe die Jacke vollgehauen hätten.” (“No assurances could be made that Mrs. Bergmann-Michel would not be molested by the unemployed. In the past, some of them had threatened a camera operator and had nearly torn his coat clean off.”)23

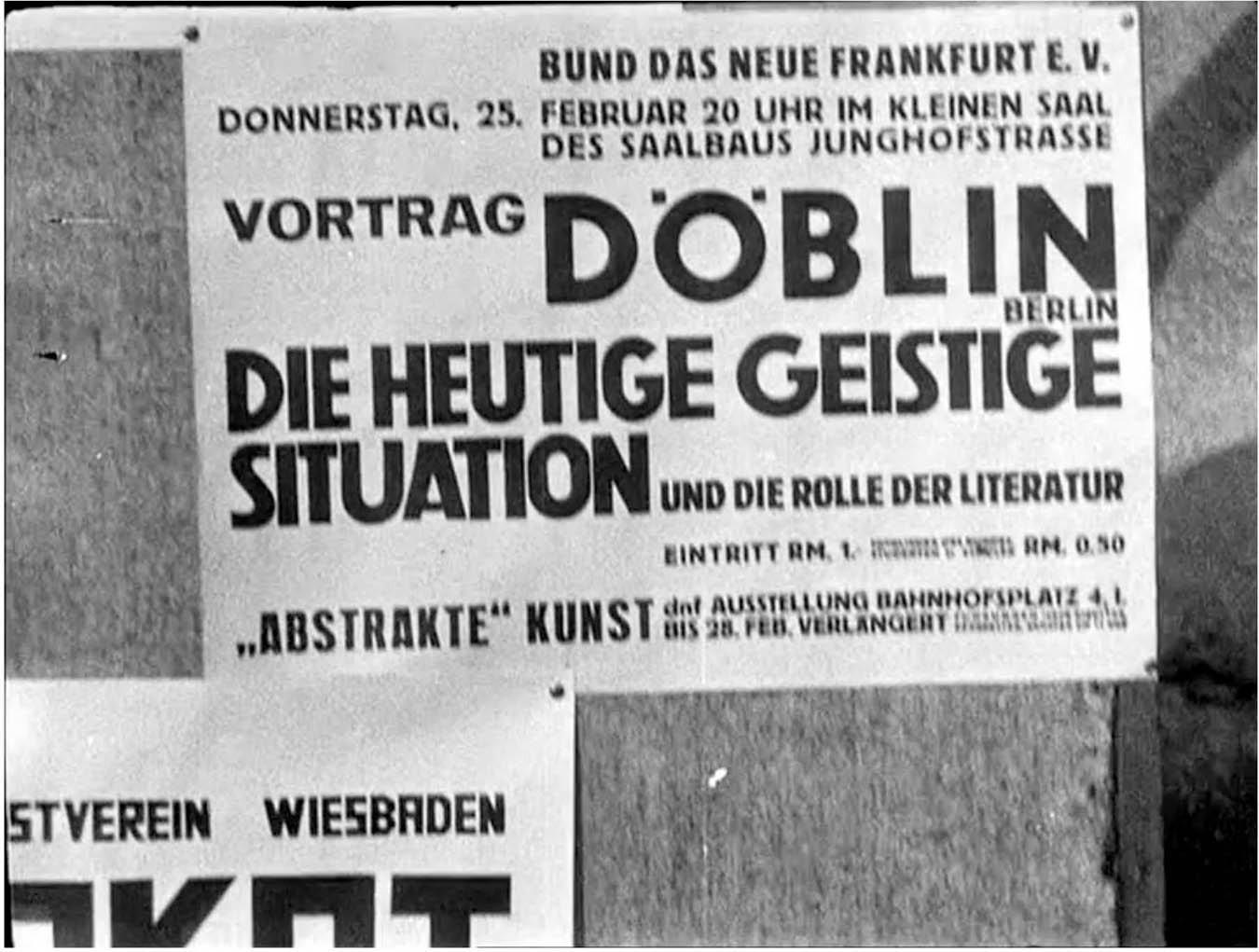

Although she never turns the camera on herself in Letzte Wahl (a neat feature that would have been possible with the Kinamo), Bergmann-Michel is omnipresent in the film—part of its query, I contend, concerning the place of the artist in a moment of political crisis. This question is presented most succinctly in the film’s final shot, a slow diagonal scan of a cluster of rare non-partisan posters advertising a talk by novelist Alfred Döblin, held almost exactly one year before he fled Nazi Germany (Figure 6.6). The topic was “The Spiritual Condition of our Day and the Role of Literature,” sponsored by das neue frankfurt. Resting on this image, the film provides no further answers, but ends by placing the figure of the artist at the center of social inquiry.

Figure 6.4: Pedestrians gathered before a Frankfurt NSDAP outfitting shop stare sternly at Ella Bergmann-Michel as she films. Screenshot.

Figure 6.5: A rally attendee heckles the filmmaker while she works. Screenshot.

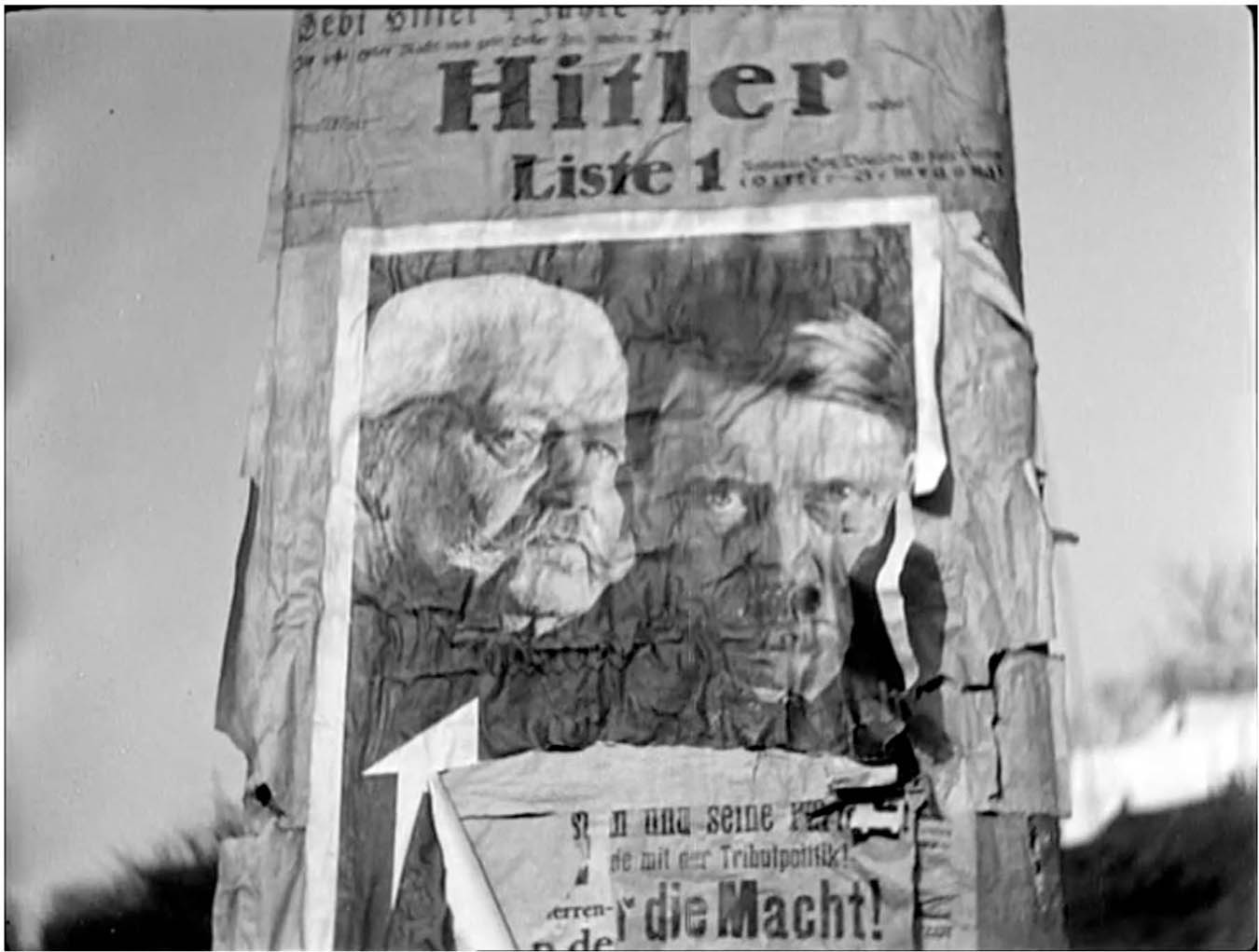

This is not all that Bergmann-Michel undertakes in this powerful little film, however. Inserted in the midst of the visual tumult of political propaganda that literally tilts left, right, and center are two brief companion shots that offer a powerful reflection on the paralyzed state of debate, and that introduce an entirely new mood into the work. The first occurs at approximately minute 1:58 and lasts around eighteen seconds: in a medium close-up, the camera trains our eyes on a tattered posted of Hitler and Paul von Hindenburg. The texture of the thin poster and the many layers of older materials that lie beneath it collectively render the candidate grotesquely wrinkled, the light and shadow of the image conspiring to make his face look skeletal as his signature mustache is reduced to a black gash (Figure 6.7). Although documentary, Bergmann-Michel’s shot here recalls certain aspects of John Heartfield’s photomontage Adolf der Übermensch: Schluckt Gold und redet Blech (Adolf the Superman: Swallows Gold and Spouts Junk), which famously features an x-ray image of the despot, his spine constructed from a column of gold coins and a swastika in place of a heart. It is possible the filmmaker knew Heartfield’s image: it first circulated in July 1932 on the cover of the magazine AIZ, and then later as a mass-produced poster, so around the time when Bergmann-Michel was shooting Letzte Wahl. In either case, Bergmann-Michel, much like Heartfield, captures the National Socialist leader as a haunting specter. Indeed, a sense of decrepitude characterizes the shot, as Bergmann-Michel trains our eye on the movement of the poster’s fluttering edge peeling away from the surface just at the level of Hitler’s cheek, threatening to eliminate the bombast’s main weapon, his mouth. Above the tear, Hitler’s domineering gaze appears, below it, the remnants of at least two previous advertisements. Although much of the text of these older posters is unreadable, two words pop out: the National Socialist buzzword “Tributpolitik” (“politics of tribute”), a term used to castigate the system of postwar reparations as a kind of modern slavery, and in larger print just below that, “die Macht,” “power.” Bergmann-Michel offers viewers a visual-verbal puzzle, the strident tone of the poster’s language and look at odds with the sensation created by her focus on the peeling of the posters, which bespeaks not only decay or decline, but also the weathering caused by the force of the elements and the various human hands that have intervened to apply each of the many layers. Training our eyes on the image for a full eighteen seconds, Bergmann-Michel also compels us to slow down and take full stock of the horror that Hitler represents.

Figure 6.6: A frame from the final shot of Letzte Wahl, of a poster advertising for a February 1932 lecture by novelist Alfred Döblin for neue frankfurt. Screenshot.

Figure 6.7: Hitler and Hindenburg stare down from a tattered poster appealing to voters before the March 1933 election that completed the Nazi takeover. Screenshot.

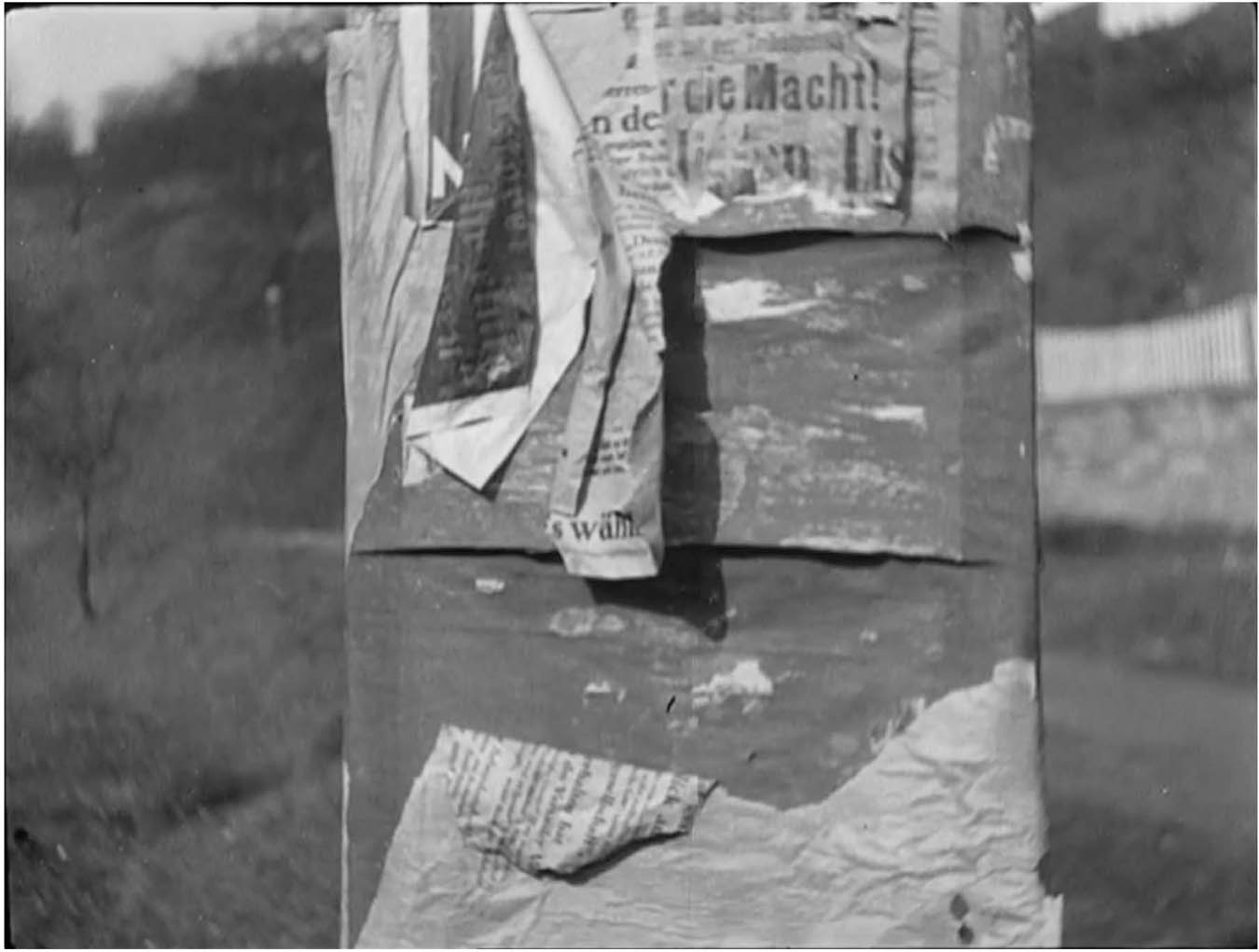

Following two separate brief scenes of pedestrians engaged in street-corner arguments, the companion shot comes just twenty seconds later, running for roughly forty-two seconds (2:35–3:17). Bergmann-Michel returns to the very same location, but presents the image of the poster from a slightly different perspective. The shot begins with the camera directed in an upward angle that captures the top of the column of posters, then tilts downward, traveling smoothly past the image of Hitler and Hindenburg, and finally comes to rest on the area immediately below the poster. Only the detritus of bygone advertisements is visible, as the remains of torn posters frame a dark zigzag of blank space, its shape echoing the jagged lines of a lightning bolt or even a swastika. We can now discern a bit more of the image’s setting as well. The column on which the poster is mounted no longer has the traditional cylindrical shape of the Littfaßsäule, but rather is slightly squared, perhaps a utility pole, and stands in a space that looks far less urban, with trees, wide swaths of grass, and a gravel footpath, giving the impression that we are now at the edge of the city space. Using a curious holding pattern, Bergmann-Michel then trains the camera on this bared section of the column for a full twenty-five seconds, or more than half of the entire shot duration (Figure 6.8). Even in a film characterized by a contemplative tempo, the decision to pause for almost half a minute (considerable time in a film that lasts only thirteen minutes in toto) on the curious image of emptiness creates a disconcerting pause for viewers, compelling us to ask, what are we looking at, or for? Bergmann-Michel offers us a palimpsest with layers that we are asked to read but are unable to—a challenge to look below the surface and imagine what might have been, or what could yet fill this space.

Certainly, these remarkable shots take aim at the figures of Hitler and Hindenburg, who appear both frightening and rather shabby. More strikingly, although these shots focus on yet another example of political propaganda, in contrast to the warring flags or the political posters described earlier, they lack a discernible counterpoint; instead, they are stand-alone moments that, I argue, are designed to engender a more contemplative mode of spectatorship. With their deliberately slow pacing and ambiguity, with the absence of clearly identifiable opposing opinions, these shots invite the viewer to stop, look, and reflect—to go deep, that is, and in so doing, to step away from the back-and-forth volley of debate. In the process, these shots suggest an alternative mode of discourse, one that eschews stark polarities and instead encourages the kinds of critical insight and dialogue essential for a healthy deliberative democracy. They point toward film as a medium especially suited to encouraging serious looking, as they direct our eyes to slow down and take the time to take in the image, to consider its significance, and perhaps even to project into the future. In this manner, the film articulates at the level of form something about the significance of art in times of cultural upheaval: it is the work of art, Bergmann-Michel seems to suggest, that may encourage us to perceive the world differently, and so perhaps to envision alternative political outcomes. In other words, she suggests that the act of reading—and more crucially, those artistic practices that make alternative interpretations possible—might constitute a form of resistance.

Figure 6.8: Below the poster of Hitler and Hindenburg, a provocative blank space that Bergmann-Michel compels us to contemplate. Screenshot.

At this point, however, the question of timing arises with particular poignancy: the poster on which Bergmann-Michel trains her camera—and our eyes—was not created for the November 1932 national election that first prompted her to capture Frankfurt street culture. In March 1932, Hitler and Hindenburg had run against each other for the position of president; the latter won. In Fall 1932, when Bergmann-Michel began her work, President Hindenburg was still seeking ways—however ineffectual—to mitigate Hitler’s power, governing by decree together with a politically weakened Chancellor von Papen. In Fall 1932, in other words, the situation was dire but not yet hopeless. The final blow to Weimar democracy would come a few months later, on January 30, 1933, when Hindenburg named Hitler chancellor, and, a day later, dissolved the Reichstag at Hitler’s behest.

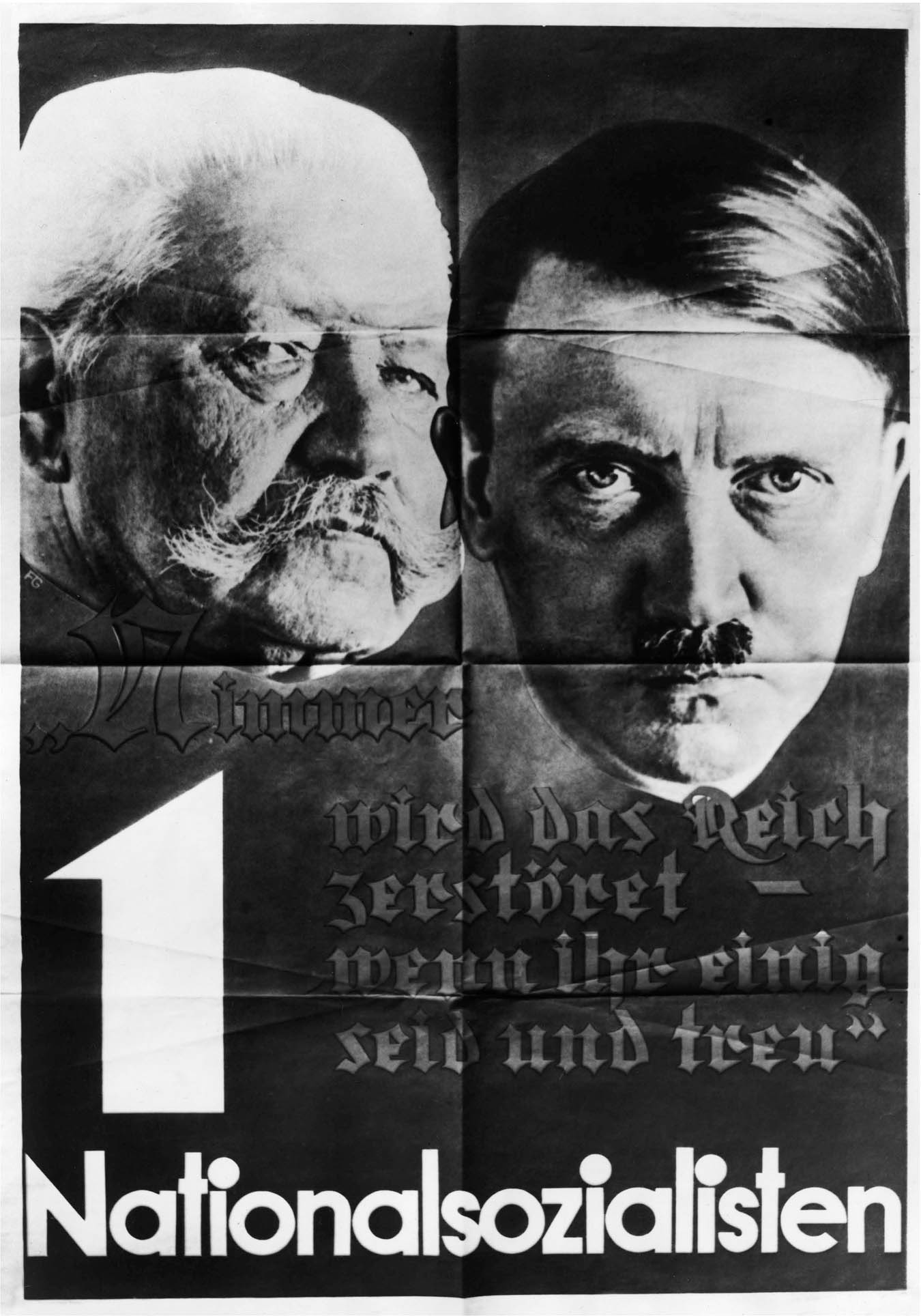

This poster—of Hitler now flanked by Hindenburg to his rear—derives from an even later moment. As a dated image from the bpk-Agentur notes, it was printed for the occasion of the March 1933 elections—i.e., post-takeover, when the relationship between Hitler and Hindenburg could now be pictured as here, with the latter appearing in the role of a supporting figure (Figure 6.9). The poster is credited to Heinrich Hoffmann, Hitler’s personal photographer and a central figure for the Nazi propaganda machine. It is not clear how long before the election the poster was printed, but it cannot have been before February. Moreover, the weathered look of the poster suggests that Bergmann-Michel probably filmed her footage even after the March election—that is, after the burning of the Reichstag, the emergency decrees that demolished remaining civil liberties, and after Hitler’s consolidation of power. The trees in the background look as though they are just beginning to bud, suggesting that the season is early spring, perhaps April. There is no way to be certain of the date, except that it was almost certainly after the fateful turn from democracy to totalitarianism that followed the March 1933 election. In other words, the poster signals the beginning of the film’s “after” moment, that is, when the tipping point in the crisis of the republic has been passed and the country finds itself in full slide toward dictatorship. It is the moment when Ella Bergmann-Michel would have been able to recognize that recent election as “final.”

This truth has been obscured until now by Bergmann-Michel’s own flawed recollections of the period. In a biographical essay drafted in 1967, she noted:

Der letzte Film blieb ein Fragment. Es waren Aufnahmen von Wahlplakaten, von lebhaften Straßen-Diskussione, von typische, den jeweiligen Parteien zugehörigen Anhängern. Die Frankfurter Straßen und Gassen bereits mit Hakenkreuz-Fahnen sowie Hammer und Sichel, und der bekannte Flagge mi den drei Pfeilen geschmückt wurden dokumentarisch festgehalten. Dann musste ich die Aufnahmen aus politischen Gründen abbrechen. —Es was Januar 1933. Filmstreifen, Fotos und Bericht brachte das vorletzte Heft 10, Jg. 6, die neue stadt, vom “bund das neue frankfurt.”

(The last film remained a fragment. There was footage of campaign posters, of lively conversations on the street, of the typical adherents of each of the parties. It documented the Frankfurt streets and alleyways already decked out with swastika flags as well as the hammer and sickle, and the famous flag with the three arrows [of the SPD]. Then I had to stop shooting for political reasons. —It was January 1933. Film strips, photos and a report were published in the next-to-last issue— 10/6—of the new city, by the “league of the new frankfurt.”)24

Figure 6.9: The complete campaign poster featuring Hitler and Hindenburg, created for the March 1932 election. The poster reads: “Never shall the Reich be destroyed if you are united and faithful.” Reprinted courtesy of Art Resource. Credit: bpk Bildagentur / Heinrich Hoffmann (1885–1957).

Certainly, it is easy to understand how Bergmann-Michel might recall ending her work in January 1933—that date, more than any other, has come to be viewed as the final caesura dividing Germany’s first democracy from Hitler’s dictatorship, and she was reconstructing her account thirty-four years later. The fact that Ella Bergmann-Michel continued to film for a brief period after the takeover sheds new light on her work in Letzte Wahl: it points toward the historical reality that the transition from democracy to totalitarianism was not, as is sometimes remembered, instantaneous, but rather occurred unevenly and over time; and it also explains the new tone that enters the film with these two remarkable sequences. For along with the feeling that Bergmann-Michel is urging her audience to slow down and contemplate the specter of Hitler, there is a certain mute dread that characterizes these images. That is, they not only point toward an alternative mode of seeing and critical reflection that is specifically tied to avant-garde artistic practices, but these startling companion shots also do this in a fashion that evokes a kind of horrorstricken and mournful gaze—a Benjaminian stare directed at the destruction behind it. Training our attention on the grim visage of the man at the helm of the project to destroy Weimar democracy, the film seems to ponder the dreadful consequence of the deadlocked climate first captured in the opening scenes of the film, and to probe whether the project of avant-garde art even has a future. The setting alone makes one curious: had Bergmann-Michel taken her camera out of the densely populated Frankfurt streets in order to document political culture on the margins, or was she perhaps seeking to avoid trouble with the police?

Although it is not a literal companion to these shots, I would like to suggest that Bergmann-Michel constructs a subtle triptych when she ends her film with the panning footage of the flyer announcing Döblin’s talk. (To picture this, imagine a sequence composed of figures 6.7, 6.8, and 6.6 from this article.—i.e., the correct order in which they appear in the actual film.) Might we not imagine that advertisement occupying the blank space beneath Hitler’s fierce gaze? Not as an “answer” perhaps but a comment, a question even. If you allow this flight of fancy, the film opens up once more as a rumination on the critical role that art must play in times of political crisis, as a force that asks us to consider more fully the cultural, intellectual, and spiritual impasses of our age and—instead of shouting—think.

By the time that Ella Bergmann-Michel finished shooting her film, Döblin had already departed Germany for exile: triply imperiled as a leftist critic of the regime, a German-Jew, and an avant-garde author, he made the decision to leave immediately following the Reichstag fire of February 26–27, 1933—almost exactly one year to the day after his Frankfurt lecture. It is uncertain when Bergmann-Michel filmed this footage of the poster, and so we cannot say whether she knew of Döblin’s departure. Could she have shot it later, as she did in the case of the poster of Hitler and Hindenburg? Certainly there is a noticeable resemblance in her framing and camera movement. Either way, there is a distinct poetic balance she creates in choosing the Döblin announcement as the concluding image for Letzte Wahl. She obviously took an interest in the novelist’s work, and the poster announcing his lecture is emblematic, moreover, for the larger impetus of the neue frankfurt movement. If that is the case, thinking of the film’s ending image as the final installment in a figurative triptych takes on an even more poignant meaning, doubly annunciating the significance of the jagged blank space of the column. Confronting us with the image of an advertisement for an event by a major intellectual who, just a year after offering a public talk on the state of German intellectual life, was forced to flee the country or face likely imprisonment, deportation, and even death (so that, from the standpoint of at least the latest historical phase represented in the film, that original event has now become impossible), Bergmann-Michel marks the dark space as both a site of potential and a marker of painful loss—at once a blank slate and a void. Working in the dark final moments of Weimar democracy, Bergmann-Michel seems to hold out some scant hope for an alternative world created through the imaginative labor of the artist, but she also records the terrible fissures already caused by the rise of Hitler’s regime. Her film offers a resistant view of the state of politics on the eve of the demise of Weimar democracy, focusing the viewer’s attention on the need to look and speak about the crises of the present with measured critical insight while also acknowledging the extent to which other, more tangible forms of resistance have become impossible. Hers is a resistance based on the work of reading between the lines—between lines of text, into the splices that connect her carefully composed cinematic images, and reading into the imaginative space that is created by the exchange of looks between the intrepid camerawoman and her subjects. In the fateful span between Fall 1932 and Spring 1933, Bergmann-Michel suggests that, however imperfect, these dual practices of critical looking and reflection may offer the only viable remaining measures for resistance, for negotiating and navigating the terms of that final choice between authoritarianism and its alternatives—and that even these limited means may now have been exhausted.

1Jutta Hercher and Maria Hemmleb, “Dokument und Konstruktion: Zur Filmarbeit bei Ella Bergmann- Michel,” Frauen und Film 49 (1990), 116.

2Ella Bergmann-Michel, “Meine Dokumentarfilme” (1967), reprinted in: Anneli Duscha, Ella Bergmann-Michel: Fotographien und Filme, 1927–1935 (Göttingen: Steidl, 2005), 80–1.

3This image of the angel, inspired by Paul Klee’s 1920 monoprint “Angelus Novus,” appears in Walter Benjamin’s 1940 essay “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” in Selected Writings, Volume 4: 1938–1940, eds Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press), 392.

4Anneli Duscha, Ella Bergmann-Michel: Fotographien und Filme, 1927–1935 (Göttingen: Steidl, 2005), 7.

5Megan R. Luke, “Our Life Together: Collective Homemaking in the Films of Ella Bergmann-Michel,” Oxford Art Journal 40.1 (2017), 31.

6Kathrin Beiligk, “Zur Werbegraphik bei Ella Bergmann-Michel,” Ella Bergmann-Michel: 1895–1971; Collagen, Malerei, Aquarelle, Zeichnungen, Druckgraphik, Fotos, Reklame, Entwürfe (Hannover: Sprengel Museum, 1990), 134–5.

7There are many brief biographical timelines available in catalogs of Bergmann-Michel’s work, but for a particularly thorough account see: Jutta May, “Biographie,” Ella Bergmann-Michel: 1895–1971; Collagen, Malerei, Aquarelle, Zeichnungen, Druckgraphik, Fotos, Reklame, Entwürfe (Hannover: Sprengel Museum, 1990), 154–8.

8May, “Biographie,” 156.

9Ella Bergmann-Michel, letter to Hans Hildebrandt, August 27, 1958. Papers of Ella Bergmann-Michel and Robert Michel, c. 1922–1971, Getty Museum, Special Collections. All translations by the author.

10Hercher and Hemmleb, “Dokument,” 107.

11Duscha, Ella Bergmann-Michel, 6.

12Duscha, Ella Bergmann-Michel, 6.

13Herta Wescher, “Die Michels, Pioniere der Bildcollage,” Ella Bergmann-Michel, Robert Michel: Collagen (Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh, 1970), 9.

14Herchner and Hemmleb, “Dokument,” 107, 109. It seems to have been common practice in the neue frankfurt movement to abandon capitalization as inefficient.

15Luke, “Our Life,” 32.

16Luke, “Our Life,” 41.

17Luke, “Our Life,” 47.

18Although we cannot know whether Ella and Robert discussed the issue, it is clear that they shared a deep sensitivity to the impact of advertising, and particularly the effects of certain text arrangements. Robert penned a fascinating short piece (which appears to be a rebuttal to a meddlesome client) regarding rules for “Verkehrsreklame” (or “advertising for public transportation”) in which he insisted on the importance of employing the largest possible vertical text and positioning it asymmetrically on the advertising column, so as to maximize its viewability for oncoming traffic and to the particular gazing habits of passengers, who he declared tended to read up and down as much as left to right. Undated memo by Robert Michel, “Erklaärungen: Reklame Säule,” in: “Papers of Ella Bergmann-Michel and Robert Michel, c. 1922–1971,” Getty Museum, Special Collections.

19Thanks to Brad Prager for first suggesting the connection between Lang’s and Bergmann-Michel’s deployment of the image of the Litfaßsäule. For more on Lang’s film, see: Anton Kaes, M (London: BFI, 2000).

20Michael K. Buckland, “The Kinamo Movie Camera, Emanuel Goldberg and Joris Ivens,” Film History 20.1 (2008), 56.

21Hercher and Hemmleb, “Dokument,” 116.

22Buckland, “The Kinamo,” 55.

23Memo of 6 April 1932, “Telephonanruf von Dr. Frey, Arbeitsamy Gallusgasse,” in: “Papers of Ella Bergmann-Michel and Robert Michel, c. 1922–1971,” Getty Museum, Special Collections.

24Ella Bergmann-Michel, “Meine Dokumentarfilme” 81. My italics. I have been unable to determine the accuracy of Bergmann-Michel’s account of the publication of her material.