Noah Soltau

On January 8, 2017, Meryl Streep walked onto the stage at the Seventy-Fourth Annual Golden Globe awards in her glittering black gown to accept a Lifetime Achievement Award. Before attendees and the public, Streep criticized then-President-Elect Donald Trump. She made a hopeful and democratic overture to the American people by imploring viewers to resist Trump’s vulgar and demeaning tendencies and to protect the free press from his authoritarian and anti-democratic attacks.1 Streep used her platform as a celebrity to protest the injustice of dominant social and political structures, and the ensuing furor across digital and social media platforms continued for days, if not weeks.

One month later, during Streep’s acceptance of an award from the gay-rights advocacy group, Human Rights Campaign, she continued her critique of the new president. Streep admitted the danger of stepping into the political arena, saying: “It’s terrifying to put the target on your forehead, and it sets you up for all sorts of attacks and armies of Brownshirts and bots and worse, and the only way you can do it is to feel you have to.”2 Streep’s guerilla take-over of the Golden Globes for political means and subsequent cautionary speech at the Human Rights Campaign awards was not her first attempt at using her celebrity for political ends. Additionally, Streep’s allusion to the “Brownshirts,” the Nazi SA paramilitary force, was not the first time she has used German history and culture, in conjunction with her celebrity status, to inspire change.

In August 2006, at the height of the Iraq war, Streep participated in a much larger, though ultimately less successful, cooperative effort at political resistance when she took the titular role in Oskar Eustis’ and Tony Kushner’s adaptation of Bertolt Brecht’s Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder (Mother Courage and her Children), which was staged for free at the Delacort Theater in Central Park.3 The production was a political and artistic attempt to resist the apparent public capitulation to mainstream narratives of both the political necessity and moral rightness of the invasion of Iraq.4 Mother Courage was one point in a constellation of Broadway productions that I have elsewhere described as “insurgent spectacles,” which attempted to confront reactionary and oppressive political and economic forces with art and encourage direct public responses, using the very trappings of the reactionary and neoliberal spectacles they undermined.5 First appearing as a response to the United States’ wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and rising domestic religious and social intolerance, the insurgent spectacles used the trappings of Broadway theater to confront audiences with politics and ideologies that ostensibly resisted those of the George W. Bush administration.

Arguably the best known and successful of these insurgent spectacles to come to Broadway was another revolutionary German drama: Steven Sater’s adaptation of Frank Wedekind’s Frühlings Erwachen: Eine Kindertragödie (Spring Awakening). Producers staged adaptations like Spring Awakening and Mother Courage in part to oppose the neoliberal Disney-fication of Broadway, and to demonstrate an alternative purpose to theater. Broadway adaptations of popular Disney films, such as Tarzan and Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark, were, they believed, the equivalent of cultural fast food: easy to consume, appealing to the widest possible market, and guaranteed to make a profit. In contrast, the insurgent spectacles offered political and ideological resistance to prevailing neoconservative social and political attitudes and policies. Unlike those Disney-inspired productions or the financially successful films they attempted to emulate, several of the insurgent spectacles offered moments of real political resistance to Bush-era policies and cultural trends.6 Mother Courage, in particular, provided an alternative to the “spectacle of terrorism,” even while co-opting the trappings of popular Broadway theater.7 However, it was less effective than many of the other insurgent spectacles, because, while the producers and actors attempted to retain their political autonomy and engage with the audience, the aura of celebrity surrounding the production pulled the audiences into the illusion of the spectacle, much like Siegfried Kracauer argues happens in the movie theater.8 Mother Courage was designed to promote citizen engagement but largely resulted in political fantasy.

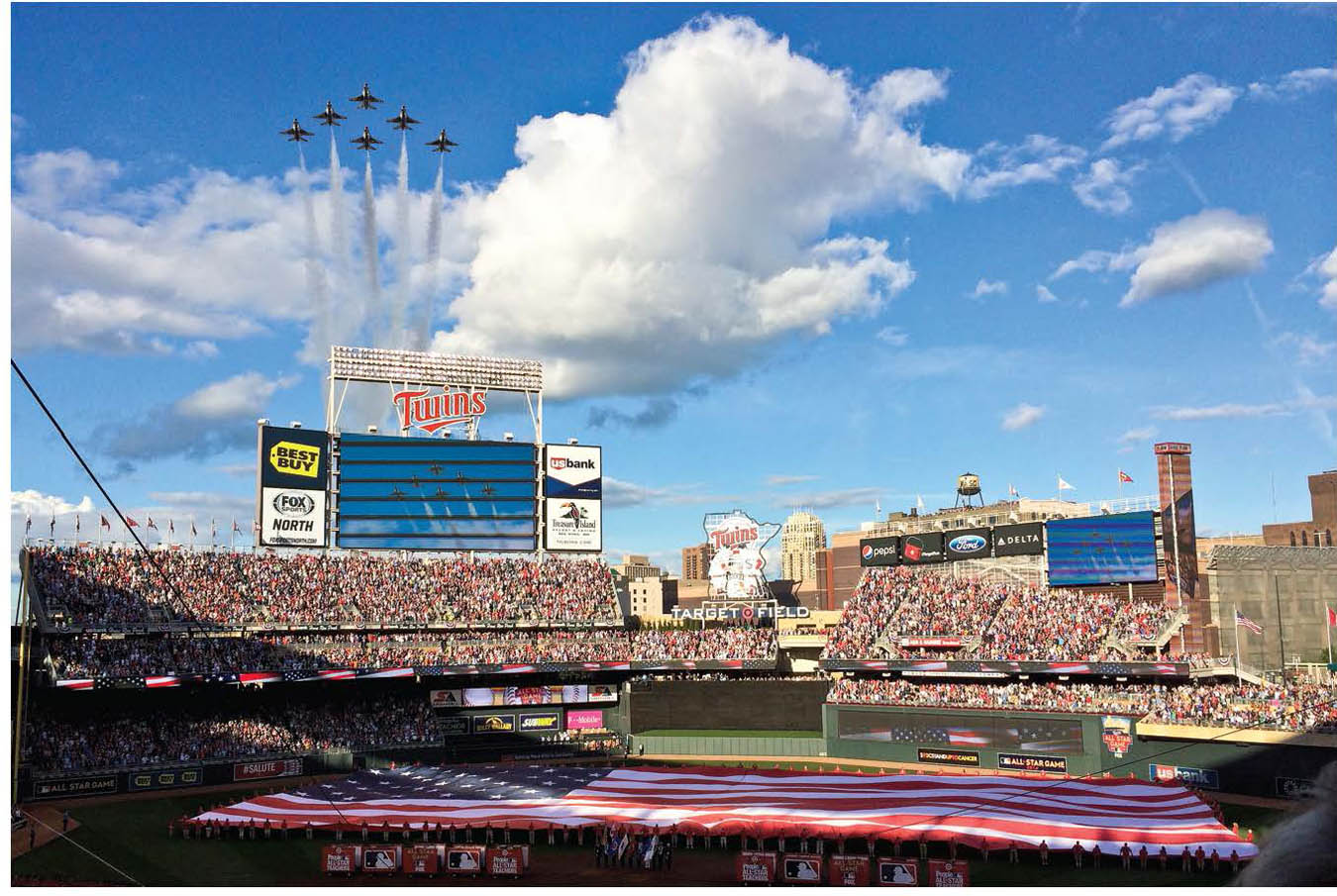

Critical theorist Henry Giroux argues that the spectacle of terrorism—the images of war, militarism, and violence that inundate television and new media—has sown chaos into our social and political lives and hobbled our democracy (Figure 7.1).This spectacle relies on marketing fear and anxiety to promote authoritarian causes and reinforce flaws and inequalities in our social structures.9 One of the most obvious ways the spectacle of terrorism influenced public discourse was the visibility of the military and veterans of the so-called War on Terror at seemingly apolitical sporting events, where the popularity of the spectacle guaranteed large audiences. From the military tributes and fly-overs at professional sporting events that began increasing in the early 2000s, to the current imbroglio surrounding National Football League (NFL) players protesting police brutality and that protest’s connection to patriotism, the spectacle of terrorism is a way to remind audiences of the state’s monopoly on violence. It uses the threat of violence from terrorists as a way of demonstrating the violence the state can enact on its enemies. Any resistance, then, to the state’s monopoly on violence (including even the appearance of anything but full-throated support for said government and its actions) is taken as an implied threat to democracy, freedom, and the American way.

Figure 7.1: The Airforce Thunderbirds aerial demonstration team flies over the opening of a Minnesota Twins game. © Department of Defense, July, 2009.

The spectacle of terrorism was so pervasive in the midst of the wars in the Middle East, that in 2004 even The New York Times was actively engaged in pushing an agenda of public fear and occupation when they argued for the existence of Iraqi chemical weapons and the invasion of Iraq even in the face of controversial and insufficient evidence.10 Under George W. Bush, the Defense Department paid professional sports teams to drum up support for the War on Terror by creating spectacles of televised flag waving and tributes to troops and veterans.11 Largely because of the public support of so many institutions for the policies of the administration, in 2006, Eustis, Kushner, and Streep found it necessary to resist outside the mainstream, in a place where the lighted screens of digital media could not reach: the theater. Much like the spectacle of terrorism imbued sporting events and cable television programming with political messaging, the stage production of Mother Courage blurred the lines between cultural and political realms. Mother Courage occupied a liminal zone in mass culture, neither an exemplary piece of radical political theater, nor an entirely co-opted cultural product. The ways Eustis and Kushner conceived and indeed misconstrued radical—in this case, Brechtian—theater, how Kushner and Streep executed that vision, and how the mainstream press interpreted Streep’s performance contributed to an understanding of the ways both celebrity and radical theater can (and cannot) resist reactionary politics within the culture industry.

Eustis, Kushner, and Streep, as well as the producers of other insurgent spectacles, like Spring Awakening, were waging ideological war on an uneven battlefield. With the co-optive power of neoliberalism taking over both the mainstream press and the Broadway theater, insurgent theater-makers were trying, as cultural critic and activist Stephen Duncombe would categorize their efforts, to “survive.”12 Extending the metaphor of “insurgent spectacles,” small, relatively powerless groups of theater-makers were using the tactics of insurgent warfare—guerrilla tactics, ambushes, training, and organizing away from surveillance by dominant powers—not to fight the prevailing cultural narrative but to merely survive as cultural producers against the spectacle of terrorism being proffered by the state. The fight waged in Mother Courage offers instructive lessons about the limits of resistance to entrenched political and economic power in this particular artistic milieu precisely because of its failure to achieve anything beyond increasing Streep’s fame or reinforcing audiences’ political attitudes.13

Eustis and Kushner took the political impetus for adapting Mother Courage from Brecht himself. In 1939, Brecht wrote Mutter Courage in a little over a month in resistance to the rise of Fascism and Nazism in Europe. Set during the Thirty Years’ War of 1618–48, the play follows the enterprising canteen woman Anna Fierling, nicknamed “Mother Courage,” who is determined not only to survive, but to profit from the war. In twelve scenes spanning twelve years, Courage hangs her fortune on the warring armies by following them with her cart of wares. Struggling, negotiating, and scrapping to survive, she loses all three of her children to the machinations of war. From the beginning of the play, Courage foreshadows the virtues that will kill her children in the war: Swiss Cheese will die for his honesty, Eilif for his bravery, and Kattrin for her kindness. Swiss Cheese is caught (badly) lying about the army to which he is loyal (while trying to save his mother’s cash box) and is shot eleven times. During a lull in the war, Eilif tries to steal some peasants’ cattle (something for which he was previously rewarded by his commanding officer) and is hanged. Kattrin rouses sleeping villagers to warn them of an attack (by the army she and her mother have been following) and is shot to death by a soldier. Courage picks up her cart and continues on. The play is not an anti-war play, but it does reveal the broken social and political institutions that grind up the virtuous and the evil alike. These institutions are corrupt and thus pay back virtue with death, and cause and reproduce suffering for its own sake—or in the service of capital.

Kushner’s adaptation follows the narrative structure of Brecht’s play, with the notable addition, in an attempt to capture Brecht’s colloquial style, of profanity, jokes, puns, and rhymes (Figure 7.2). The staging, too, starts with Brecht: a timeline removed from contemporary events, intertitles, scene breaks announced in a flat voice regardless of the drama on stage. Kushner then departs from Brecht and lays on the spectacle with cannon fire, whole squads of troops dying in exploding ruins, the stage machinery whirring, and jeeps rolling on and off the stage. The final departure from Brecht is the music, scored by Jeanine Tesori, and Streep’s energetic singing, which take the play out of a bombed-out Berlin in 1949 (the first time it was staged) and sets it firmly down on Broadway.

Figure 7.2: Meryl Streep as Mother Courage in the Delacort Theater production. © Kino Lorber/Kanopy, 2008.

Eustis included Kushner and Streep in an attempt to give Brecht, and more importantly his subversive politics, renewed mass appeal in the US. Yet the ploy backfired: Streep’s emotionally moving performance in Kushner’s adaptation eclipsed and undermined the aesthetic tools of politically conscious theater. Theater critic Ben Brantley picked up this fault in the production when he reviewed the show, writing, “Mother Courage should open for Ms. Streep the same future in advertising endorsements that awaits grand-slam sports champions. I, for one, would love to know what vitamins she takes and how to get them.”14 The popularity of Streep-doing-Brecht was not in doubt; in fact, it was the problem. Similar to the time McDonald’s famously co-opted Kurt Weill’s “Mack the Knife”—a murder ballad from Brecht’s Threepenny Opera about class-politics—in advertisements during the 1980s to sell cheeseburgers and Coca-Cola products,15 Mother Courage underscores the difficulty of resistance within the culture industry.16

In an interview with The New York Times in 2007, Eustis foreshadowed the power of neoliberal capitalism to co-opt even the most revolutionary voices, when he used a Meissen china plate decorated with Brecht’s smiling face to illustrate the difficulty of being a celebrity trying to engage in cultural resistance.17 Eustis recognized that there is something deceptive about an image of a clean-shaven, smiling Brecht (neither attribute for which the cantankerous Brecht was particularly well-known) applied to such obvious kitsch.18 He found humor and a hint of warning in this image of Brecht—someone both so politically engaged and averse to the habits and trappings of bourgeois existence—immortalized and smiling on a knick-knack. However, Eustis was also convinced that the best response he could mount to the horror of the Iraq war was to have Tony Kushner adapt a Brecht play performed by celebrities in Central Park, merchandizing be damned.

As part of an aesthetic and political insurgency into Broadway theater, Eustis and Kushner had one chance for their play to go off like a bomb. Conscious of the Iraq war as a motivator of the production, at a time when reports of casualties from Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) were constant, the dramaturgical approach to political content as explosive was timely. The components of the bomb—crude language, humor, music, and star power—were intended to react and effect political change among theater viewers and broader American society alike. This should have been an explosive production. Instead, if the insurgent spectacle can be described as a kind of IED, then Mother Courage was a dud. The producers’ misapprehension of Brechtian theatrical technique as well as the social circumstances surrounding the production meant Mother Courage became the deterrent rather than the impetus for political change.

The celebrities themselves, Streep and Kushner, actively opposed the political inaction to which their efforts would fall victim. They were horrified by the apparent public acceptance of the invasion of Iraq and the War on Terror and frustrated with the way the mainstream media were in lockstep with the political goals of the administration. In response, they tried to use their fame and Brecht’s drama to inspire political action from people who felt the same.

In Voicing Dissent, Violaine Roussel and Bluewenn Lechaux outline the perceived power that celebrities have in political arenas. The “figure of the ‘engaged celebrity’ defines his/her civic role as the result of a direct relation with a public: the symbolic coup at work is based on the equivalence stated between ‘having audiences’ and ‘having constituencies,’ justifying the self-assignation of an ability/legitimacy to speak for others, especially for voiceless people, here against the war.”19 The false equivalence between audiences and constituencies; Eustis’s over-estimation of the extent to which celebrity leveraged into radical theater could help him resist the spectacle of terrorism; and Kushner and Streep’s own misjudgment of how their celebrity would be used, divorced from the politics of the play, all worked against the play’s efficacy as an act of cultural resistance.

Because the play’s producers misread both Brecht and the social conditions into which they adapted the play, Mother Courage did not achieve its potential political or critical resonance. As the critic Robert Brustein noted, Brecht “helped turn our Pepsodent smile into a Weimar sneer.”20 When Brecht wrote Mutter Courage, he did so under the rubric of Epic Theater and made extensive use of Verfremdungseffekte (alienation effects). He conceived that the mechanics of Epic Theater, including colloquial language, humor, and extradiegetic songs, would detach audiences from the action of the play and arouse them intellectually rather than emotionally. Epic Theater would thereby transform them from spectators into engaged observers and encourage them to take political action.21 Brecht knew that disrupting emotional connections with the characters would be difficult, which is why he made use of so many alienating techniques. But in Eustis and Kushner’s adaptation, there was tension between the content of the text, its staging, and popular response to the production that may have defined the limits of theater-as-politics, in particular when the driving force of that theater is celebrity, as critic Georg Monbiot argues, is the “smiling face of the corporate machine.”22

Brecht thought that the artist could harness the trappings of popular culture to inspire the proletariat to effect social and economic change, but his mid-twentieth-century theories about European society were an anachronism on twenty-first-century Broadway that undercut his intent.23 Whereas Brecht, in the 1940s, tried to rouse audiences to political consciousness through appeals to their ethics and intellect, in 2006 Kushner appealed to their passion and emotional bewilderment. He placed Mother Courage at the epicenter of the terrible effects of war, which set the tone for the political critique she attempted to make as part of the spectacle. For instance, at the beginning of the fourth scene, after Courage’s son Swiss Cheese has been killed and she refuses to claim his body out of fear of reprisal, Kushner inserts her as an engaged observer of a dispute between an aggrieved soldier and his guilty commander. The soldier storms onto the stage, shouting: “I’m not letting myself get fucked like this. You come outside right now and let me cut your fucking head off!”24 This violent outburst sets the stage for a confrontation, but as the scene plays out and Courage encourages him to be reasonable, the obscenity and passion lessen, the soldier’s conviction fades, and the expected conflict and resolution never come. Both the soldier and Courage slink away, beaten and embittered, before either gets the justice that they both deserve—justice they ultimately realize they cannot expect or even fight for.

Mother Courage underlines the central problem with Broadway theater and perhaps all commercial art as a means of resistance to political crisis. Art cannot respond to war in kind. Art or an individual artist can only produce representations of social and political positions and perspectives. Describing his sense of frustration over the political situation, Kushner wrote, “I can’t get out of bed and it’s fucking horrible and I don’t know what to do. I don’t know what to do. I don’t know what to do. And nobody knows what to do.”25 Instead of direct action—which he admitted is the most effective way to resist authoritarianism and crisis—he adapted a play. Eustis and Kushner’s political theater, in which entertainment replaces social engagement, falls into the same trap of which Theodor Adorno wrote decades earlier, namely, it “treats conflict but in fact proceeds without conflict.”26

And this was not the only ideological or theoretical problem of using Brecht to resist the broad cultural support for an unjust war of occupation. Kushner seems to read Brecht as if the social structures and the material history that Brecht engaged were still in place. However, even shortly after the Second World War, the renowned East German playwright Heiner Müller recognized that Brechtian techniques could no longer create democratic spaces within the theater, even under the political and economic framework of socialism.27 But, on Broadway, Brecht still retains some ideological and political currency, if only in the form of nostalgia and with a whiff of high culture.28 Kushner recognized this and tried to leverage it into resisting, or at the very least protesting, the effects of the War on Terror.

Kushner uses a slightly modified Brechtian technique, crude language, to reckon explicitly with the way that war reorders and flattens our collective life. It comes early on in the play, when a soldier remarks on the state of the civilians, “The problem with these people is they haven’t had enough of war.… Everything rots in peacetime. People turn into carefree rutting animals and nobody fucking cares.”29 Kushner’s use of crude language heres draw attention to the paradox of war (which is inimical to life) as a projection of strength, when in fact it is ultimately an expression of moral and human failure. The spectacle of terrorism, like Brecht’s Thirty Years’ War, projects strength while promoting weakness. The false projection of strength, both in war and under the aesthetic regime of the spectacle of terrorism, is also seductive. Ultimately, Kushner’s Mother Courage could not respond in kind, either aesthetically or ideologically, to the spectacle of terrorism. Its media dominance and “pedagogy of fear” are simply too effective at creating “the conditions for transforming a weak American democracy into a dangerous authoritarian state.”30 As Brecht tried to warn audiences in Mutter Courage, the political institutions grind up the virtuous and the evil alike.

Kushner, like Brecht, weaves this metaphor of the seeming futility—and yet necessity—of resisting overwhelming systems of power into the play with the Epic Theatrical device of humor. First, he has the Chaplain (played by Austin Pendleton) tell a joke about Martin Luther that underscores the longevity of giant systems of inequality and avarice: “Martin Luther met a priest who was begging for alms by the side of the road. Luther said to the beggar priest, ‘After I turn the world inside out we won’t need priests!’ ‘Maybe not,’ said the priest, ‘but you’ll still need beggars,’ and he went on his way.”31 At the end of the same scene, Courage herself weighs in on the predicament: “We’re prisoners, but so are head lice.”32 Here Courage concisely sums up her role and those of her family in the world: to feed off the lives (and deaths) of those around them. These moments are laconic and might even elicit a chuckle, but they also lay bare the vast powers arrayed against anyone (the audience) who wants to escape the exploitative system. The recognition of the collective response of laughter in the face of those powers to which Mother Courage refers can create solidarity among audience members even as they are confronted by their dire political circumstances.

Kushner claimed his spectacle aimed to remind people that “[we] make and are made by history.… [Like] all great plays Courage demands that its audience think, and think hard, about what it’s seeing and hearing, but no one watching Mother Courage can watch it cold or remain unmoved.”33 For example, Kushner has Courage and the Cook (Courage’s erstwhile companion, played by Kevin Kline) engage in a darkly comic political debate that lays out the stakes of war for them and for the audience. The Cook points out to Courage the necessary but problematic nature of torture, a clear allusion to Abu Ghraib and another instance where Kushner ties the aesthetic devices of the insurgent spectacle to the particular historical moment of the Iraq war. Torture, the Cook quips, “adds to the cost of the war, since contrary to expectations the Poles have preferred to remain unliberated, the King’s tried everything, the rack and the screw and the prisons are expensive, and when the King discovered they didn’t want to be free, even after torture, he stopped having any fun.…”34 Courage quickly rejoins that the Poles thoughts on liberation are irrelevant: “The King will never be defeated, and why, his people believe in him, and why? Precisely because everyone knows he’s in the war to make a profit.… If it’s business, it makes sense.”35 This political conversation is very clearly meant to parallel the audience’s own condition, as well as implicate them in the war. Kushner’s text contains the potential to motivate political action, but audiences were left overwhelmingly with the sense of how entertaining political theater could be. While Brecht did indeed intend his plays to move his audiences, it was to move them out into the streets and their social circles, to motivate political and social change, not to bewilder them or have them empathize with Courage. Kushner’s seems to suggest that he wanted the audience to be moved emotionally, which undermines the play’s fierce criticism of war, religion, and capitalism.

Brecht designed the aforementioned alienation effect and other Epic Theatrical techniques to disrupt emotional connection. Brecht wanted audiences to engage in a kind of dialectical relationship even with their own empathy, not to be forced into it.36 Empathizing with a war-profiteer like Courage does not fit into a political program designed to resist the acceptance of the neoliberal economy of war in which Kushner saw the US engaged.37 Interrogating that empathy and recognizing that even Courage, “one of those lower-class Capitalists” and “hyena of the battlefield,” loses everything but her life in the war she profits from should make audiences and critics interrogate their own social systems that duplicate that suffering, not feel badly for or even admire Courage.38

Streep’s charisma as Courage, as well as the moving and emotional score from Tesori, also caused the potentially revolutionary work to misfire. Rather than disrupt the narrative and diegetic space of the play and draw the audience’s attention to politics, the music as sung by Streep unified the performance and created a decidedly un-Brechtian illusionism. In arguably the defining musical moment of the production, Courage sings “The Song of Great Capitulation.” Spare piano accompaniment joins Courage’s voice, sometimes slightly ahead, sometimes behind, to create an awkward dissonance as Courage gives in to the despair of having to deny knowing her dead child in order to keep her business.

(Singing.) I’d accepted that I’d only got the shit that I deserved. On my ass, or on my knees, I took it with a grin.

(Speaking.) You have to learn to make deals with people, one hand washes the other one, your head’s not hard enough to knock over a wall.

(Singing.) Birdsong from above:

Push comes to shove.

Soon you fall down from your grandstand

And join the players in the band

Who tootle out that melody:

Wait, wait and see.

And then: it’s all downhill.

Your fall was God’s will.

Better let it be.

Many folk I’ve known planned to scale the highest peak.

Off they go, the starry sky high overhead.

(Speaking.) To the victor go the spoils, where there’s a will there’s a way, at least act like you own the store.39

The moment should have engaged audiences to consider their responsibility for the war, but instead it leaves audiences heartbroken at Courage’s tribulation and loss.40 This gap between the stimulus (war) and the response to it (the production of theater) is a space created by the culture industry, one of politics-as-entertainment, rather than politics-as-action. By atomizing the body politic and by treating politics and war as spectacle, mass culture encourages passivity and the consumption of outrage and emotion rather than promoting organized political action in the public sphere.

Kushner may have tried to hedge his bets and create the space for audiences to achieve emotional distance with other musical numbers. Toward the end of the play, a starving Cook sings “The Song of Solomon.” In the song, the Cook attempts to get an innkeeper to open his doors to him and Courage not out of virtue, but under threat of theft and violence, critiquing virtue and showing how useless it is in this world.41 Kline’s delivery of the song—complete with “jazz hands” and awkward looks out into the audience—underlined at once the scene’s silliness (he is literally singing for his supper) and served as a foil for the despair and desperation of the interstitial spoken lines. Audience members laughed and nodded their heads with the melody, but there remained tense stillness and recognition, at least among some critics, that this part of Courage’s world was an uncanny proxy of their own.42 This montage of unsettling techniques was meant to promote, if not political action, then at least political awareness. But outside of the theater, particularly in the popular press that covered the production, that political awareness, much less a discussion of political action, was largely absent.

It was political awareness and an understanding of the fraught historical moment out of which Brecht wrote, that convinced Streep to leverage her star power for a political purpose and take on the role of Courage. The potential of Mother Courage to effect political and social change was not lost on other artists at the time either, as John Walter’s 2008 documentary about the production, Theater of War, demonstrated. The film explores the creation of the production and in it, Streep said of her role in the spectacle:

I’m the voice of dead people. So … I’m the interpreter of lost songs, and I’m the person who, you know, filtered through the sensibility of right now, 2006, with everything we know, I’m the interpreter. I’m between the audience that’s going to hear it and my sense of what language they understand and the person who wrote it years ago and conceived it—Brecht.43

Assuming this almost metaphysical role of mediator between the dead, Brecht, and the audience, Streep sought to leverage her celebrity to fulfill what she perceived as a political need, while concurrently shedding that celebrity to fulfill an artistic function.44 She also understood very well the emotional and intellectual platform that music gives to the actor, beyond speech. She said, “I wanted to make [the play]—it’s because of the lullaby, [which] we see over and over and over and over on television, Lebanon, Srebrenica, women, just going ‘Why?!’ over the body of their children. ‘Why?!’ That’s what it was. That’s the whole thing. For me.… What’s the end result? Bones in the landscape.”45 Streep’s insight into the potential of this work of art is both enlightening and infuriating to her political allies. The bones in the landscape have piled up, unceasingly, in the intervening twelve years.

Mother Courage is off the stage, but Streep is still an enormously accomplished actor. The subtlety of the continuing effects of Streep’s celebrity is compelling. Unlike the majority of women in Hollywood who are sold and marketed as sex symbols, Streep is marketed for her skill as an actor.46 Audiences line up to see her in whatever medium, not to be titillated, but to be “cultured” and to witness her craft. Like classical music performances for Adorno, Streep represents the commodity of high culture.47 She is the sign of serious art, and of liberal social and aesthetic sensibilities. And now, as then, in the age of tribal politics, anti-elite sentiment, disenfranchisement, disaffection, and anti-intellectualism, those signs heavily circumscribe her audience. Streep’s available audience then consumes that image, embracing her role as purveyor of middle-class commodity culture. That perceived cultural and social power was exactly what Kushner and Streep were trying to use for their own political ends, but their spectacle’s lack of self-reflexivity on its use of stardom and its self-selecting audience ultimately contributed to the play’s equivocal critical reception.

The reification of Brecht and Mother Courage and the lack of engagement with its politics and the concomitant critique of power, fame, and spectacle compromised the production’s political efficacy and trickled down to the way Streep as Courage was treated in the public sphere. Hilton Als wrote for the New Yorker: “It’s difficult to see Meryl Streep the actress without being dazzled by Meryl Streep the legend.”48 In perhaps the only indication that the gears of the culture industry faltered a little because of Streep’s performance in Mother Courage, Als ends his critique of her as Courage by noting, “Her grandeur is merely a façade, she seems to be telling us, and she is as committed to the job at hand as any other conscientious working actress.”49 The appeal to a workman-like performance, of sacrificing her glamor on the altar of art, is attractive and useful to the program of establishing theater as an effective response to dominant forms of spectacle and political agendas. However, almost all the other voices from the audience undermined Als’ observation. Jeremy McCarter (though he is one of the rare critics that gestures to the techniques and politics of Mother Courage) put it succinctly when he noted: “Of course, it’s not the prospect of seeing unforgiving German drama that has people camping out for tickets. However equivocal the result, Streep in ‘Mother Courage’ represents a genuine episode in New York stage history.”50 The equivocal result, timely political theater undermined by spectacle and stardom, is the legacy of Mother Courage.

Mother Courage was neither simple spectacle nor subversive political theater. It did not draw the same audiences or critical regard as either Tarzan or The Gay Slave Handbook, to cite examples of other spectacles on offer in New York in 2006, from two ends of the theater spectrum. This alloy of conflicting politics and ideology can only be partially attributed to the context surrounding the production, the actors and celebrities involved, and the media coverage. The conflict is also essential to the text; it is the problem constantly posed by Brecht’s work, and is something Kushner achieves in his adaptation: the inability to reduce its conflicts to specific political functions. For example, in a conversation with Courage about the (terrifying) possibility of peace, the Chaplain elucidates the problem both of effective political theater and seemingly intractable global conflict in a moment of drunken clarity. He is optimistic about the certainty of perpetual war:

Wars get stuck in ruts, no one saw it coming, no one can think of everything, maybe there’s been short-sighted planning and all at once your war’s a big mess. But the Emperor or the King or the Pope reliably provides what’s necessary to get it going again. This war’s got no significant worries as far as I can see, a long life lies ahead of it.51

Ultimately, Kushner’s Mother Courage became a story about the struggle for survival and a challenge to change the social circumstances in which that struggle occurred. The play’s call to consider the sources and causes of the US’s wealth were inimical to the smooth function of the culture industry. As a result, the culture industry adapted itself to Mother Courage’s mode of spectacle, requiring potential elements of opposition to fight merely to exist, rather than to resist, because, as Courage notes, “war feeds its people better.”52

However, artistic resistance to political regimes and existential threats from the culture industry are never wasted efforts. In reading Ben Brantley’s critical review of the production, the effects of the schema of mass culture, both on this production and the aesthetic sensibilities of members of the audience, become vivid. He argues that the elements of the spectacle do not form a “fully integrated and affecting portrait” except, ironically, “when Ms. Streep sings the Brechtian songs that have been newly (and effectively) scored by Jeanine Tesori.”53 In fact, Brantley is so impressed by Streep-the-greatest-living-actress when he should be the most alienated by her Brechtian performance, that—due to her athletic dramatic performance—he ironically suggests a future in advertising for her and then seriously hints at a possible future for her as “queen of the Broadway musical.”54 The nexus of celebrity, commodity, and entertainment that Brantley saw in Streep’s performance shows precisely how theater that uses the tactics of asymmetric warfare has the potential to function (though it failed in this case) and how the schema of mass culture co-opts those tools to fulfill its own ends.

One of celebrity’s primary functions is to sell, not just products, but ideology.55 Brantley’s invocation of Brecht without any apparent understanding of how “Brechtian” songs should function (certainly not as a “seamless, astonishing whole”), the comparison of Streep to a sports figure (with the implied advertising opportunities), and the insistence on a monolithic, consistent spectacle all betray the deleterious effects that fetishized celebrity and the schema of mass culture can have on political theater, and more broadly, commercial art. As other recent scholarship on the reception and production of theater has shown, Mother Courage was compromised because the assumed audience turned out to expect a “fully integrated,” “astonishing” production that makes full use of Streep’s celebrity capital.56 That celebrity capital, in fact, is all that many critics could focus on. Reviews from the Washington Post, USA Today, New York Daily News, and the New York Observer focused solely on Streep on stage and made no mention of the techniques of the production or its politics.57

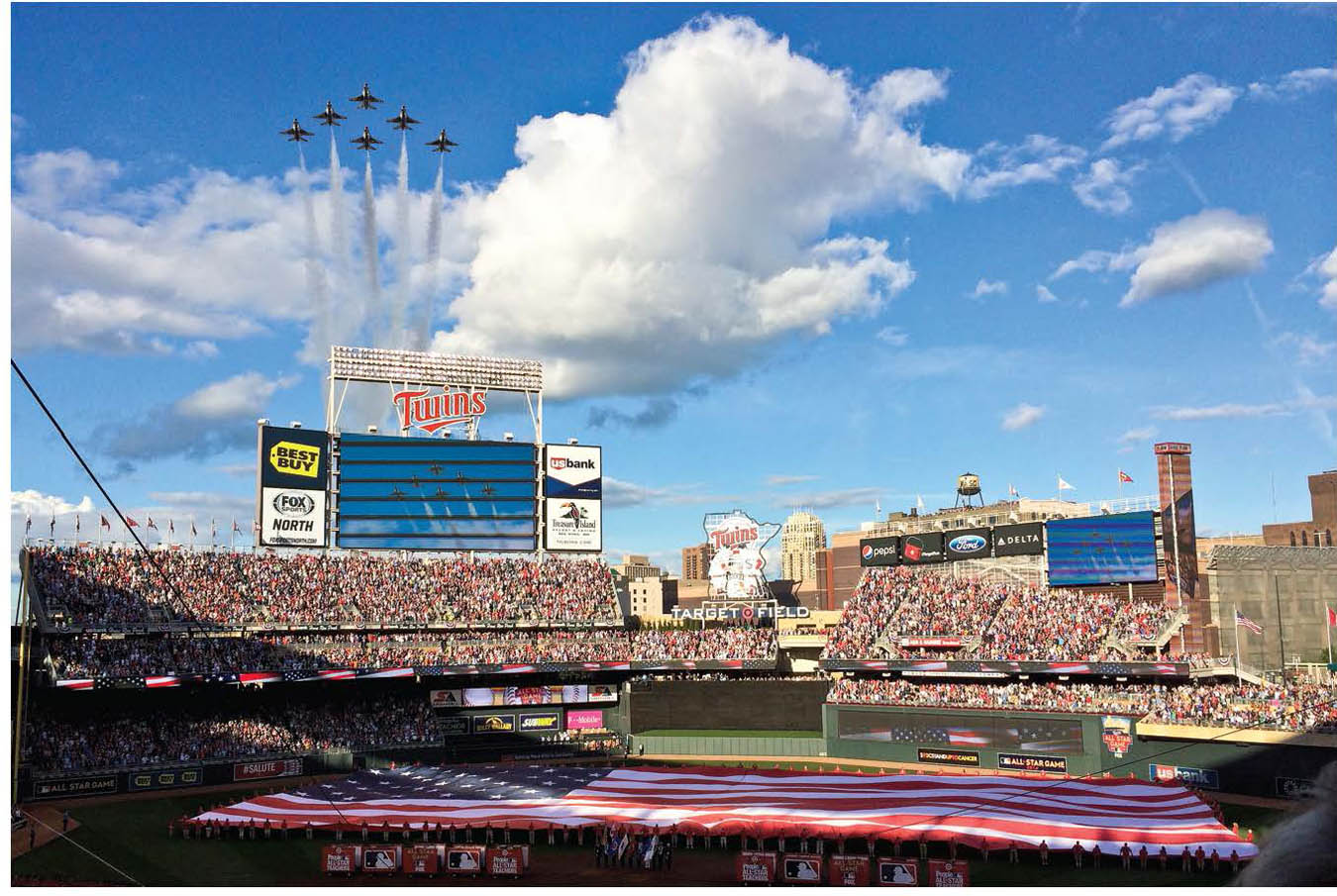

Streep’s interviews in Walter’s Theater of War demonstrate that she cannot simply remove her mantle of celebrity when she chooses, nor can she choose how her celebrity affects or is perceived by her audience.58 Even in the way she is sometimes costumed, like at the 2012 Oscars, she appears both as herself and as an image of something else (Figure 7.3).59 The fetishizing of celebrity happens not only in relation to the stars of the production and the audience, but also in relation to Brecht and to the participants in this particular performance. To quote Kushner’s soldier, the political goals of the play were “fucked” from the start.60

Figure 7.3: Meryl Streep at the 2012 Academy Awards. © Associated Press, 2012.

As a painful irony, Brecht’s own celebrity also compromised this production from the outset. Brecht is famous with theatergoers because he wrote compelling, cantankerous political theater that criticized Nazis, Western capitalism, and bureaucratic socialism with equal vigor. He made a laughing-stock of Joseph McCarthy and helped shape dramatic theory and dramaturgy in Germany, the UK, and the US.61 But it was his reputation and his fame from which Eustis and Kushner were trying to draw their political agency, rather than from a critical negotiation with his theory, politics, and critique of social structures and conditions. As Streep put in in her now-famous Golden Globes acceptance speech: “An actor’s only job is to enter the lives of people who are different from us, and let you feel what that feels like.”62 By her own understanding, Streep succeeded as an actor, but in Mother Courage, she failed to produce the political activity she so clearly desired.

The primary lesson critics and artists can learn both from Mother Courage and the current climate in Washington is that celebrity generally offers pyrrhic victory in the political arena. Even radical political statements in a spectacular format are susceptible to co-option. The volatile mixture of celebrity and politics in the US (but also throughout Western Europe, Russia and the former Soviet Republics, and East Asia) reveals the consequences of mediated social relationships and the political colonization of almost every aspect of public life. Kushner’s scripted ideological response to the horrors of war and late neoliberal capitalism, the mediated sparring between celebrity activists and celebrity politicians, the New York and Beltway-centered reception to both: all reveal a lack of authenticity and historical consciousness. This undermines public discourse and public trust in the figures and systems upon which the politically and socially conscious public has traditionally relied to reduce the chaotic influence of personality cults and irresponsible politics. The difficult solution, and one toward which it seems both Streep and Kushner were striving, would be to de-colonize our public, artistic, and intellectual spaces from the political and social forces that are preying upon and destabilizing them. US Americans’ attention, politics, histories, and daily lives are for sale to a myriad of interests with an equally wide array of political, social, and economic goals. These same US Americans have been complicit with and passive in the face of that selloff. Because of this, these decades-old problems of freedom, art, and robust public life have only compounded.63 It remains to be seen whether the current trends in Western democracies toward nativism, nationalism, and jingoism (with Brexit, Alternative für Deutschland [AfD, the right-wing “Alternative for Germany”], and France’s Le Front national party, for example) will spur the re-examination of the power of celebrity in the public sphere, but Mother Courage’s lessons and Streep’s recent public sparring with Trump offer a possible solution: reveal the wielders and structures of power, reveal their weaknesses, and promote solidarity and political action in the public.

1Daniel Victor and Giovanni Russonello, “Meryl Streep’s Golden Globes Speech,” The New York Times, January 8, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/

2Sopan Deb, “Meryl Streep Pledges to Stand Up,” The New York Times, February 12, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/

3I was able to see the August 19, 2006 production of Mother Courage.

4In the interest of clarity, “Mutter Courage” will refer to Brecht’s 1939 play, while “Mother Courage” will indicate Tony Kushner’s 2006 adaptation.

5Noah Soltau, “Insurgent Spectacles: Spring Awakening, Woyzeck, Mother Courage and the ‘New’ Broadway Spectacle” (PhD. diss. University of Tennessee, 2014), 5–7, 26.

6Soltau, “Insurgent Spectacles,” 97, and Siegfried Kracauer, trans. Thomas Levin, “The Little Shopgirls Go to the Movies,” in The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995), 291–2.

7Henry Giroux, Beyond the Spectacle of Terrorism: Global Uncertainty and the Challenge of the New Media (Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers, 2006).

8Kracauer, 293–4, 297, 303.

9Giroux, Beyond the Spectacle of Terrorism.

10“From the Editors; The Times and Iraq,” May 26, 2004, http://www.nytimes.com/

11“NFL Kickoff Live from the National Mall Presented by Pepsi Vanilla,” August 5, 2003, https://www.businesswire.com/

12Stephen Duncombe, ed. Cultural Resistance Reader (London: Verso, 2002), 8.

13Soltau, “Insurgent Spectacles,” 57–9.

14Ben Brantley, “Mother Courage, Grief and Song,” The New York Times, August 26, 2006. https://www.nytimes.com/

15See Mathew Sheffield’s piece for Salon from October 25, 2016, https://www.salon.com/

16Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment ed. Gunzelin Schmid, trans. Edmund Jephcott (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2002), 107. Horkheimer and Adorno conceive of popular culture in terms of a factory, wherein standardized products of mass culture are produced to manipulate and pacify the population. The schema of mass culture would be the means of and techniques whereby the culture industry exerted its influence.

17David Colman, “Citizen Brecht Puts on His Happy Face,” The New York Times, April 15, 2007, http://www.nytimes.com/

18David Colman, “Citizen Brecht.”

19Violaine Roussel and Bluewenn Lechaux, Voicing Dissent: American Artists and the War on Iraq (New York: Routledge, 2010), 22.

20Jonathan Kalb, “Still Fearsome, Mother Courage Gets a Makeover,” The New York Times, August 6, 2006, http://www.nytimes.com/

21Ekkehard Schall, The Craft of Theatre: Seminars and Discussions in Brechtian Theater (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015), 205.

22George Monbiot, “Celebrity isn’t just harmless fun,” The Guardian, December 20, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/

23Philip Glahn, “21st-Century Brecht,” Afterimage 38:6 (2011), 12–15.

24Bertolt Brecht, Mother Courage and her Children: A Chronicle of the Thirty Years’ War, translated by Tony Kushner, (London: Methuen Drama, 2009), 53.

25John Walters, Theater of War, DVD, 2008.

26Adorno, “Schema of Mass Culture,” in The Culture Industry: Selected Essays on Mass Culture, (New York: Routledge, 1991), 71.

27Michael Wood, Heiner Müller’s Democratic Theater: The Politics of Making the Audience Work, (Rochester, New York: Boydell and Brewer, 2017), 14.

28Kalb, “Still Fearsome.” Brecht’s relatively far-reaching influence on American theatrical culture is often taken for granted. Marc Bilstein’s 1954 Production of The Threepenny Opera ran for seven years on Broadway, and many of Brecht’s other works are staples among avant-garde and university theaters, popularized in particular during the Vietnam era.

29Brecht, Mother Courage, 7.

30Giroux, Beyond the Spectacle of Terrorism, 18.

31Brecht, Mother Courage, 39.

32Brecht, Mother Courage, 39.

33Jonathan Kalb, “Interview with Tony Kushner,” in Communications from the International Brecht Society, ed. Norman Roessler, Volume 35 (Fall 2006), 99.

34Brecht, Mother Courage, 34.

35Brecht, Mother Courage, 34.

36Anne Beggs, Brecht and the Culture Industry: Political Comedy on Broadway and the West End, 1960–1965, dissertation, (Cornell University, 2009), 71.

37Kushner, Communications.

38Robert Brustein, The Theater of Revolt: An Approach to Modern Drama (Boston: Little, Brown, 1991), 272.

39Brecht, Mother Courage, 56–7.

40Kalb, “Still Fearsome.”

41Brecht, Mother Courage, 89–91.

42Jeremy McCarter, “The Courage of their Convictions,” New York Magazine, August 22, 2006, http://nymag.com/

43John Walter, Theater of War, Alive Mind, 2008, DVD.

44Hilton Als, “Wagon Train,” The New Yorker, September 6, 2006, https://www.newyorker.com/

45John Walters, Theater of War.

46Wheeler Winston Dixon and Gwendolyn Audrey Foster, 21st-Century Hollywood: Movies in the Era of Transformation (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2011), 159.

47Adorno, “The Schema of Mass Culture,” 68.

48Als, “Wagon Train.”

49Als, “Wagon Train.”

50McCarter, “The Courage of their Convictions.”

51Brecht, Mother Courage, 63.

52Brecht, Mother Courage, 70.

53Brantley, “Mother, Courage, Grief and Song.”

54Brantley, “Mother, Courage, Grief and Song.”

55Christopher Bell, American Idolatry: Celebrity, Commodity, and Reality Television, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2010), 73.

56Wood, Heiner Müller, 155–7.

57http://www.simplystreep.com/

58Christopher Bell, American Idolatry, 73.

59Jack Shepherd, “Oscars 2017: Meryl Streep hits out at dress designer who ‘defamed’ her,” The Independent, February 26, 2017, http://www.independent.co.uk/

60Brecht, Mother Courage, 53.

61Chris Westgate, Brecht, Broadway, and United States Theater (Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholar’s Publishing, 2007), xv–xvi.

62Victor and Russonello, “Meryl Streep’s Speech.”

63Lena Partzsch, “The Power of Celebrities in Global Politics,” Celebrity Studies 6:2 (2015), 178–91.