Glasgow is a diverse and lively city. And yet there are few places in Europe that have been more publicly misunderstood and misrepresented. A city that has divided opinion, Glasgow exhibits the best and worst of commerce and capitalism, stunning architectural feats amid gritty urban scenery, and constant renewal and reinvention. Glasgow has – over the centuries – been a small fishing village, an industrial powerhouse, and a hotbed for severe social problems. Few cities can have changed so much, displayed so much character, or ignited so much controversy.

The Stock Exchange building.

Mockford & Bonetti/Apa Publications

Cosmopolitan Glasgow

Yet even in the darkest days of its reputation, when Glasgow’s slums and violence were the touchstone for every sociologist’s worst urban nightmare, it was still a city for connoisseurs. It appealed to those who were not insensitive to the desperate consequences of its 19th-century population explosion, when the combination of cotton, coal, steel and the River Clyde transformed Glasgow from elegant little merchant city to industrial behemoth; and who were not blind to the dire effect of 20th-century economics which, from World War I onwards, presided over the decline of its shipbuilding and heavy industries; but who were nevertheless able to uncover, behind its grime and grisliness, a city of nobility and invincible spirit.

Oversized seating outside the Riverside Museum.

Mockford & Bonetti/Apa Publications

Its enthusiasts have always recognised Glasgow’s qualities, and even at the height of its notoriety they have been able to give Glasgow its place in the pantheon of great Western cities. Today, it is fashionable to describe the city of Glasgow as European in character, for the remarkable diversity of its architecture and a certain levity of heart, or to compare it with North America for its gridiron street system and wisecracking street patter.

But these resonances have long been appreciated by experienced travellers. In 1929, at a time when social conditions were at their worst, the romantic but perceptive travel writer H.V. Morton found ‘a transatlantic alertness about Glasgow which no city in England possesses’ and – the converse of orthodox opinion – was able to see that ‘Edinburgh is Scottish and Glasgow is cosmopolitan’.

Modern Glaswegians have further reason to celebrate – Glasgow was voted the ‘friendliest city in the world’ by two separate polls in 2014.

Fists of iron

The Glaswegian comedian Billy Connolly said of Glasgow: ‘There’s a lightness about the town, without heavy industry. It’s as if they’ve discovered how to work the sunroof, or something.’ Yet Glaswegians themselves will admit that their positive qualities can have a negative side. Even today, mateyness can turn to menace, especially if there is alcohol involved. Religious bigotry – generally between Catholics and Protestants – the obverse of honest faith, simmers just below the surface, spilling out onto the streets and football terraces, although the city worthies are constantly trying to find ways to contain it. And Glasgow’s legendary humour, made intelligible even to the English through the success of comedians like Billy Connolly, but available free on every street corner, is the humour of the ghetto. It is dry, sceptical, irreverent and often dark.

Culture city

Glasgow today is visibly, spectacularly, a city in transformation. It hasn’t allowed its ‘hard, subversive, proletarian tradition’ to lead it into brick walls of confrontation with central government. The result? A city which has massively rearranged its own environment; which sees its future in the service industries, in business conferences, exhibitions and indeed in tourism; which has already achieved some startling coups on its self-engineered road to becoming ‘Europe’s first post-industrial city’; and which has probably never been more exciting to visit since, at the apogee of its Victorian vigour, Glasgow held the International Exhibition of Science and Art more than 100 years ago.

The Glasgow City coat of arms in stained glass, Glasgow Cathedral.

Mockford & Bonetti/Apa Publications

Glaswegians allow themselves a sly smile over their elevation to the first rank of Europe’s cultural centres. (It was European City of Culture in 1990, UK City of Architecture and Design in 1999, and hosted the Commonwealth Games in 2014.) But the smile becomes a little bitter for those who live in those dismal areas of the city as yet untouched by the magic of stone-cleaning, floodlighting or even modest rehabilitation.

Defenders of the new Glasgow argue that their turn will come; that you can’t attract investment and employment to a city, with better conditions for everyone, unless first you shine up its confidence on the inside and polish up its image on the outside.

View from Queen’s Park.

Mockford & Bonetti/Apa Publications

Hills and water

Like the other four main Scottish cities, Glasgow is defined by hills and water. Its suburbs advance up the slopes of the vast bowl that contains it, and the pinnacles, towers and spires of its universities, colleges and cathedral occupy their own summits within it. It is, therefore, a place of sudden, sweeping vistas, with always a hint of ocean or mountain just around the corner.

Look north from the heights of Queen’s Park and you will see the cloudy humps of the Campsie Fells and the precipitous banks of Loch Lomond. Look west from Gilmorehill to the great spangled mouth of the Clyde and you will sense the sea fretting at its fragmented littoral and the islands and resorts that used to bring thousands of Glaswegians ‘doon the watter’ for their annual Fair Fortnight.

The antiquity of this July holiday – Glasgow Fair became a fixture in the local calendar in 1190 – gives some idea of the long-term stability of the town on the Clyde. But for centuries Glasgow had little prominence or significance in the history of Scotland. Although by the 12th century it was both a market town and a cathedral city (with a patron saint, St Mungo) and flourished quietly throughout the Middle Ages, it was largely bypassed by the bitter internecine conflicts of pre-Reformation Scotland and the running battles with England.

Most of Scotland’s trade, too, was conducted with the Low Countries from the east coast ports. But Glasgow had a university, now five centuries old, and a distinguished centre of medical and engineering studies, and it had the River Clyde. When trade opened up with the Americas across the Atlantic, Glasgow’s fortune was made.

Fact

Today, the names of the streets of 18th-century Glasgow – like Virginia Street and Jamaica Street – tell something of the story which turned a small town into the handsome fief of tobacco barons, and hint at a shameful ‘profit’ from the slave trade.

The tobacco trade with Virginia and Maryland brought the city new prosperity and prompted it to expand westwards from the medieval centre of the High Street. (Little of medieval Glasgow remains.) In the late 18th century the urbanisation of the city accelerated with an influx of immigrants, mainly from the West Highlands, to work in the cotton mills with the new machines that had been introduced by merchants who had been forced to desert the tobacco trade. The Industrial Revolution had begun, and from then on Glasgow’s destiny – grim and glorious – was fixed.

Instant city

The deepening of the Clyde up to the Broomielaw, near the heart of the city, in the 1780s and the coming of the steam engine in the 19th century consolidated a process of such rapid expansion that Glasgow has been called an ‘instant city’. In the 50 years between 1781 and 1831 the population of the city quintupled, and was soon to be further swelled by thousands of Irish immigrants crossing the Irish Sea to escape famine and seek work. The Victorians completed Glasgow’s industrial history and built most of its most self-important buildings, as well as the congested domestic fortifications that were to become infamous as slum tenements. Since World War II, its population has fallen below the million mark to fewer than 600,000, the result of policies designed to decant citizens into ‘new towns’ and the growing appeal of commuting from green-belt villages and towns.

Glasgow Green

One translation of the original Celtic suggests that the city’s name, Glasgow, means ‘dear green place’. Other translations include ‘dear stream’ and ‘greyhound’ (which some say was the nickname of St Mungo), but the green reference is most apt, for Glasgow has, after all, more than 70 parks – ‘more green space per head of population than any other city in Europe’, as the tour bus drivers will proudly tell you.

The most unexpected, idiosyncratic and oldest of its parks – in fact, the oldest public park in Britain – is Glasgow Green, once the common grazing ground of the medieval town and acquired by the burgh in 1662. To this day Glaswegians have the right to dry their washing on Glasgow Green, and its Arcadian sward is still spiked with clothes poles for their use, although there are few takers. Municipal Clydesdale horses, used for carting duties in the park, still avail themselves of the grazing, and the eccentricity of the place is compounded by the proximity of Templeton’s Carpet Factory, designed in 1889 by William Leiper, who aspired to replicate the Doge’s Palace in Venice. (The factory is now a business centre.)

Here, too, you will find the People’s Palace 1 [map] (tel: 0141-276 0788; Tue–Thu, Sat 10am–5pm, Fri, Sun 11am–5pm; free), built in 1898 as a cultural centre for the East End community, for whom its red-sandstone munificence was indeed palatial. It’s now a museum dedicated to the social and industrial life of the 20th-century city.

Statue of Eve in the Kibble Palace, Botanic Gardens.

Mockford & Bonetti/Apa Publications

The most distinguished of the remaining 69-odd parks include the Botanic Gardens 2 [map] (tel: 0141-276 1614; www.glasgowbotanicgardens.com; daily 7am–dusk, glasshouses 10am–6pm, winter until 4.15pm; free) in the heart of Glasgow’s stately West End, with another palace – the Kibble Palace – the most enchanting of its two large hothouses. It was built as a conservatory for the Clyde-coast home of a Glasgow businessman, John Kibble, and shipped to its present site in 1873. The architect has never been identified, although legend promotes Sir Joseph Paxton, who designed the Crystal Palace in London.

Across from the gardens is one of Glasgow’s most popular cultural centres, Òran Mór (tel: 0141-357 6200; www.oran-mor.co.uk) set in the converted Kelvinside Parish Church. All manner of theatre, live music and dance events are held here, including the ever-popular A Play, A Pie and A Pint series, and there’s a range of bars, restaurants and cafés.

Other parks and gardens

Kelvingrove Park 3 [map] , in the city’s West End, was laid out in the 1850s and was the venue of Glasgow’s principal Victorian and Edwardian international exhibitions, although that function is now performed by the modern Scottish Exhibition and Conference Centre on the north bank of the Clyde (for more information, click here). It is a spectacular park, traversed by the River Kelvin and dominated on one side by the Gothic pile of Glasgow University (this seat of learning was unseated from its original college in the High Street and rehoused on Gilmorehill in 1870) and by the elegant Victorian precipice of Park Circus on the other side.

‘Floating Heads’ installation in the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum.

Mockford & Bonetti/Apa Publications

The Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum 4 [map] (tel: 0141-276 9599; Mon–Thu, Sat 10am–5pm, Fri, Sun 11am–5pm; free) includes a major collection of European paintings and extensive displays on the natural history, archaeology and ethnology of the area. Rembrandt, Matisse and Van Gogh are just three of the great artists on exhibit here, while there’s also a superb focus on Scottish art, from the Colourists to the Glasgow Boys. It has a magnificent organ, which is regularly used for recitals, and in the main hall a World War II Spitfire hangs from the ceiling, above the vast stuffed elephant known as Sir Roger.

Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum.

Mockford & Bonetti/Apa Publications

Victoria Park, near the north mouth of the Clyde Tunnel, has a glasshouse containing several large fossil trees some 350 million years old.

Pollok Country Park 5 [map] on the city’s south side (those who live south of the Clyde consider themselves a separate race of Glaswegian) has a well-worn path beaten to the door of the Burrell Collection (tel: 0141-287 2550; free; closed for refurbishment until 2020), where there are more than 9,000 exhibits, from artefacts of ancient civilisations, to medieval treasures, to Impressionist paintings, including a wonderful Degas exhibition. It was all lovingly gathered together by the shipping tycoon Sir William Burrell, who donated the whole lot to the city in 1944, although a suitable exhibition space couldn’t be found for almost 40 years, when the current site opened in 1983. Also in the park is the 18th-century Pollok House (tel: 0141 616 6410; daily house 10am–5pm, gardens until dusk), designed by William Adam. It, too, is an art gallery, with works by El Greco, Murillo, Goya and William Blake. The windows look out on a prizewinning herd of Highland cattle and Pollok Golf Course.

Not far away, towards East Kilbride, is Rouken Glen, another lovely area of parkland with a walled garden and tumbling waterfall.

Also on the city’s south side, south of Queen’s Park in Cathcart, stands Holmwood House (tel: 0141 571 0184; Easter–Oct Thu–Mon noon–5pm, last entry 4pm), the best domestic example of the work of Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson, Glasgow’s most famous Victorian architect. It was built in 1857–8 for a paper manufacturer, James Couper.

‘Le Château de Médan’ by Cézanne, Burrell Collection.

Mockford & Bonetti/Apa Publications

River Clyde

Stobcross Quay on the north bank is the site of the ultramodern Scottish Exhibition and Conference Centre (SECC) 6 [map] (www.secc.co.uk) and the Clyde Auditorium, known as The Armadillo, a 3,000-seat concert venue designed by Lord Foster. Adjacent to these two vast buildings, another, The Hydro opened in September 2013 to complete this trio of entertainment venues. It is the city’s main location for large music concerts and comedians’ arena-style tours. You can also marvel at the industrial colossus of the Finnieston Crane, now redundant from its original use for lifting heavy machinery but an admirable (and some might say beautiful, in its own way) testament to the importance of the Clyde in days gone by.

Fact

Glasgow District Subway, opened in 1896, was one of the earliest underground train systems in Britain and the only one in the country that is called, American-style, ‘the Subway’.

Across Bell’s Bridge is the Glasgow Science Centre 7 [map] (tel: 0141-420 5000; www.glasgowsciencecentre.org; summer daily 10am–5pm, winter Wed–Fri 10am–3pm, Sat–Sun 10am–5pm), a collection of futuristic buildings that includes Glasgow’s IMAX Cinema, with an 80ft (24-metre) -wide screen; the Science Mall, a hands-on extravaganza where visitors can explore, create and invent; a planetarium; and the Glasgow Tower, the tallest free-standing structure in Scotland and the only one in the world that will rotate through 360 degrees; the views are spectacular.

To the west, beyond Stobcross Quay and adjacent to Glasgow Harbour, the £74-million futuristic Riverside Museum 8 [map] (tel: 0141-287 2720; Mon–Thu, Sat 10am–5pm, Fri, Sun 11am–5pm; free) opened to great acclaim in 2011 and has since become one of Britain’s most popular attractions, even winning the European Museum of the Year award in 2013. Replacing the former Museum of Transport, this purpose-built glass-fronted space houses every manner of transport that has at one time or another graced Glasgow’s streets, from horse-drawn omnibuses to old trams and vintage cars from the 1930s to the 1970s. The railway system is not forgotten either, with four locomotives from different time periods, while overhead a velodrome of bicycles displays life on two wheels over the ages. Two streetscapes have also been created, reimagining shops, pubs, sounds and aromas from the 1890s to the 1960s. The permission to ‘climb aboard’ many of the exhibits makes the museum particularly fun and exciting for children. In summer the forecourt in front of the museum is awash with food stalls, buskers and the occasional brass band.

Behind the museum is The Tall Ship (tel: 0141-357 3699; www.thetallship.com; daily Mar–Oct 10am–5pm, Nov–Mar until 4pm), a restored 19th-century three-masted barque named the Glenlee that is now permanently moored so that visitors can explore what life was like on deck for crews who once sailed as far afield as Asia and Australia. As well as the crews’ cabins there’s an onboard hospital area and a galley kitchen.

Death on the Clyde

The old adage that ‘the Clyde made Glasgow and Glasgow made the Clyde’ cannot be taken as a true description of the relationship today. In his book In Search of Scotland, journalist and writer H.V. Morton describes the launching of a ship on the Clyde in a passage that brings tears to the eyes: ‘Men may love her as men love ships … She will become wise with the experience of the sea. But no shareholder will ever share her intimacy as we who saw her so marvellously naked and so young slip smoothly from the hands that made her into the dark welcome of the Clyde’. That was written in 1929 – at a time when the Clyde’s shipbuilding industry was on the precipice of the Great Depression from which it never recovered.

Soon, another writer, the novelist George Blake, was calling the empty yards and silent cranes ‘the high, tragic pageant of the Clyde’, and today that pageant is nothing more than a side-show. Not even the boost of demand during World War II, nor replacement orders in the 1950s, not even the work on supply vessels and oil platforms for the oil industry in the 1970s, could rebuild the vigour of the Clyde. Today Glasgow no longer depends on the river for its economic survival but developments like the Clyde Walkway, the Glasgow Science Centre and the Riverside Museum represent a new future for the river as part of the leisure industry.

A recreated Glasgow street scene in the Riverside Museum.

Mockford & Bonetti/Apa Publications

A cultural explosion

After the decline of the shipbuilding industry, Glasgow turned its mind to creating a more refined city of culture, winning loud applause for its combination of design, modern architecture and café lifestyle.

Glasgow’s elevation to the position of European City of Culture in 1990 (a title bestowed by the European Community) was received with a mixture of astonishment and amusement in Edinburgh, which had long perceived itself as guardian of Scotland’s most civilised values.

But, quietly, Glasgow had been stealing the initiative. Edinburgh had been trying to make up its mind for nearly 30 years about building an opera house, but Glasgow went ahead and converted one of its general-purpose theatres, the Theatre Royal, into a home for the Scottish Opera and venue for Scottish Ballet. The city is also home to two major orchestras and the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama.

Besides its traditional theatres – the King’s and the Pavilion – Glasgow has the Tramway Theatre 9 [map] (www.tramway.org), the former home of the city’s trams and now an internationally acclaimed contemporary visual and performing-arts theatre. Peter Brook inaugurated the theatre in 1988 when he staged his nine-hour epic Mahabharata, contributing to the cultural explosion that would lead to the city’s prestigious title in 1990.

Studio theatres include the Tron, founded in 1979, the Mitchell Theatre, housed in an extension of the distinguished Mitchell Library, and two small theatres in the dynamic Centre for Contemporary Arts on Sauchiehall Street. However, Glasgow’s most distinctive stage is the innovative Citizens Theatre ) [map] (www.citz.co.uk) started in 1943.

Each year, it seems, Glasgow adds a new festival to its calendar. The West End Festival, the city’s biggest, has been followed by international jazz, cabaret and piping festivals, each held during successive summer months to keep visitors coming.

Distinguished art galleries

The turning point in Glasgow’s progress towards cultural respectability came with the opening, in 1983, of the striking building in Pollok Country Park to house the Burrell Collection, bequeathed to the city in 1944 and now under major refurbishment. Until recently, the enormous popularity of the Burrell Collection has tended to overshadow Glasgow’s other distinguished art galleries and museums: Kelvingrove, at the western end of Argyle Street, which has a strong representation of 17th-century Dutch paintings and 19th-century French paintings as well as many fine examples of the work of the late 19th-century Glasgow Boys; the Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA), opened in 1996; the university’s Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery; and the St Mungo Museum of Religious Life and Art.

Architecture and design

In 1999, The Lighthouse, designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh and formerly the offices of The Herald, reopened as an architecture and design centre, with displays on the work of Mackintosh, and exhibition galleries. Other museums of note are Haggs Castle, a period museum, on the South Side and the miniature repository of social history, the red sandstone Tenement House ! [map] (Mar–June, Sept–Oct daily 1–5pm, July–Aug Mon–Sat 11am–5pm, Sun 1–5pm) a two-room-and-kitchen flat in an 1892 tenement in Garnethill, wonderfully preserved. The former Museum of Transport has now made way for the exciting Riverside Museum on the Clyde, which opened in 2011.

The Clyde Walkway

Stobcross Quay is also a terminus of the Clyde Walkway, an area that has been part of a £1-billion 9-year-long ‘Clyde Waterfront Regeneration’ scheme introducing new residential and leisure developments to the once heavily industrialised banks of the Clyde. It is possible to walk from the quay through the centre of the city past Glasgow Green to the suburb of Cambuslang, but in its entirety it stretches 40 miles (64km) all the way to the Falls of Clyde at New Lanark (for more information, click here). It’s particularly popular with cyclists, offering wonderful vistas without the pressures of motor traffic and links up with other cycle routes such as Glasgow to Inverness or Edinburgh.

Before you reach George V Bridge and Central Station’s railway bridge, you come to the Broomielaw, an area rich in sailing history and being regenerated into the rapidly expanding financial services district with modern offices and hotels. It was once the departure point for regular services to Ireland, North America and the west coast towns and islands of Scotland. You can sail from here on the world’s last seagoing paddle steamer, the Waverley (tel: 0845-130 4647; www.waverleyexcursions.co.uk; July–Aug Mon–Fri, times vary), which cruises during the summer to the Firth of Clyde, the Ayrshire coast and the Isle of Bute.

The Hydro arena on the Clyde.

Mockford & Bonetti/Apa Publications

Custom House Quay @ [map] , which looks across to the delicately restored Georgian facades of Carlton Place on the south bank, is also the subject of a major regeneration project.

The central section of the walkway is the most interesting, taking in the city’s more distinguished bridges and many of the buildings associated with its maritime life. The two most impressive bridges are the pedestrian Suspension Bridge and the Victoria Bridge. The Victoria Bridge was built in 1854 to replace the 14th-century Old Glasgow Bridge, and the graceful Suspension Bridge was completed in 1871, designed by Alexander Kirkland, who later became the Commissioner of Public Buildings in Chicago.

There is also new life on the inner-city banks of the Clyde, as cranes and wharves are replaced by modern residential apartments. On the south bank, near Govan, up-market apartments have been built at the old Prince’s Dock, the £20-million Clyde Arc links the Finnieston Quay with the BBC Scotland complex on the south bank at Pacific Quay, and the massive Rotunda at the north of the old Clyde Tunnel, designed for pedestrians and horses and carts, has been restored as a restaurant complex.

Other opportunities to get on the river are offered by Seaforce (tel: 0141-221 1070; www.seaforce.co.uk), which runs powerboat trips from beside The Tall Ship, and the Clyde Waterbus, a river taxi between the Broomielaw and Braehead.

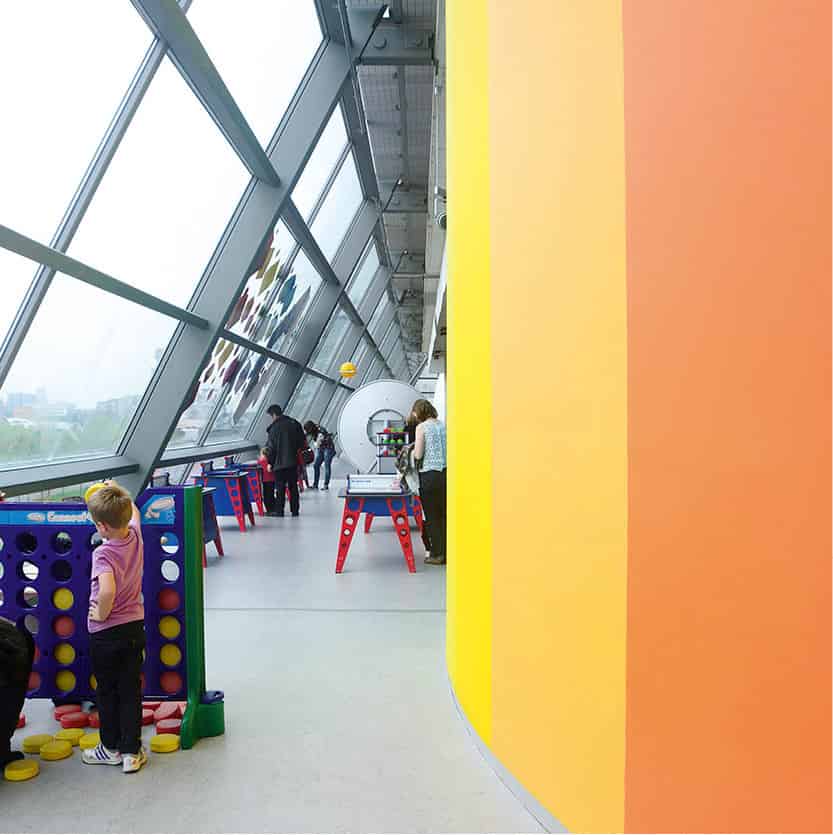

Interactive games in the Glasgow Science Centre.

Mockford & Bonetti/Apa Publications

Tip

Hampden Park, in the south of the city, has been redeveloped as Scotland’s National Football Stadium, with a museum of Scottish football (tel: 0141-616 6139; www.scottishfootballmuseum.org.uk; Mon–Sat 10am–5pm, Sun 11am–5pm).

The built environment

‘Rough, careless, vulnerable and sentimental.’ That’s how the Scottish poet Edwin Morgan, who died in August 2010 aged 90, described Glaswegians, and they are certainly qualities that Glaswegians have brought to their environment. The city has been both brutal and nostalgic about its own fabric, destroying and lamenting with equal vigour. When the city fathers built an urban motorway in the 1960s they liberated Glasgow for the motorist but cut great swathes through its domestic and commercial heart, and were only just prevented from extending the Inner Ring Road, which would have demolished in the process much of the Merchant City. But the disappearance of the last trams in the 1960s has been regretted ever since, even though Glaswegians have grown to love the ‘Clockwork Orange’ – the violently coloured underground transport system.

But to Morgan’s list of adjectives might have been added ‘showy’ and ‘aspirational’, two sides of the architectural coin that represents Glasgow’s legacy of magnificent Victorian buildings. They aren’t hard to find: the dense gridiron of streets around George Square and westwards invites the neck to crane at any number of soaring facades, many bearing the art of the sculptor and all signifying some chapter of the city’s 19th-century history.

George Square and Merchant City

George Square is the heart of modern Glasgow. Like most Scottish squares, it contains a motley collection of statues, commemorating 11 people who seem to have been chosen by lottery. The 80ft (24-metre) column in its centre is mounted by the writer Sir Walter Scott, gazing southwards, so they say, to the land where he made all his money. But the square is more effectively dominated by the grandiose City Chambers £ [map] (tel: 0141-287 4018; ground floor only Mon–Fri 8.30am–5pm, guided tours Mon–Fri at 10.30am and 2.30pm; free) designed by William Young and opened in 1888. The marble-clad interior is even more opulent and self-important than the exterior. The pièce de résistance is the huge banqueting hall, 110ft (33 metres) long, 48ft (14 metres) wide and 52ft (16 metres) high; it has a glorious arched ceiling, leaded glass windows and paintings depicting scenes from the city’s history. The south wall is covered by three large murals, works of the Glasgow Boys (for more information, click here).

George Square’s other monuments to Victorian prosperity are the former Head Post Office on the south side (now the main Tourist Information Centre) and the noble Merchants’ House on the northwest corner (now home to the Glasgow Chamber of Commerce). Its crowning glory is the gold ship on its dome, drawing the eye ever upwards – a replica of the ship on the original Merchants’ House.

Today the whole area south of George Square and down to Argyle Street is collectively known as Merchant City. The grandiose warehouses and mansions erected by the suddenly wealthy tobacco magnates of the late 18th and early 19th centuries have been preserved in all their exterior glory and converted into a bustling area of up-market shops, restaurants and cafés, many of which put out pavement tables on sunny days giving the whole area a decidedly European feel. It’s one of the most influential and successful aspects of Glasgow’s 1980s regeneration projects.

Window detail on the Merchants’ House.

Mockford & Bonetti/Apa Publications

Just off Buchanan Street is Nelson Mandela Place (its name having been changed from St George’s Place in tribute to the South African political leader, who was granted Freedom of the City in 1993). Here you will find the Glasgow Stock Exchange $ [map] , designed in the 1870s by John Burnet, whose reputation was to be eclipsed by his celebrated son J.J. Burnet; and the Royal Faculty of Procurators (1854).

Nearby are examples of the work of another distinguished Glasgow architect, the younger James Salmon, who designed the Mercantile Buildings % [map] (1897–8) in Bothwell Street and the curious Hat-rack in St Vincent Street, named for the extreme narrowness and the projecting cornices of its tall facade. Further west, J.J. Burnet’s extraordinary Charing Cross Mansions ^ [map] of 1891, with grandiloquent intimations of French Renaissance style, were spared the surgery of motorway development which destroyed many 19th-century buildings around Charing Cross.

Trades Hall.

Mockford & Bonetti/Apa Publications

Magnificent terraces

On the other side of one of these motorways are the first buildings of the Park Conservation Area. These edifices have given rise to the statement that Glasgow is the ‘finest piece of architectural planning of the mid-19th century’. Take a stroll upwards through this area to a belvedere above Kelvingrove Park and marvel at the glorious vistas.

The belvedere is backed by Park Quadrant and Park Terrace, which are probably the most magnificent of all the terraces in the Park Conservation Area. Still in the West End, in Great Western Road, you will find Great Western Terrace & [map] , one of the best surviving examples of the work of Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson, the architect who acquired his nickname as a result of his passion for classicism.

Back towards the city centre in St Vincent Street is Thomson’s prominent St Vincent Street Church * [map] . It is fronted by an Ionic portico, with sides more Egyptian than Greek and a tower that wouldn’t have been out of place in India during the days of the Raj. Here the streets rise towards Blythswood Square, which was once a haunt of prostitutes but now, with its surroundings, provides a graceful mixture of late Georgian and early Victorian domestic architecture.

Fact

No. 7 Blythswood Square was where Glasgow socialite Madeleine Smith allegedly poisoned her French lover in 1858, although the jury returned a verdict of ‘not proven’. She later moved to London, entertained George Bernard Shaw and married a pupil of the designer William Morris.

Art and architecture

In Buchanan Street is the Glasgow Royal Concert Hall (tel: 0141-353 8000; www.glasgowconcerthalls.com), a purpose-built venue that regularly attracts top artists and orchestras. Behind St Vincent Place is Royal Exchange Square, which is pretty well consumed by the city’s Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA) ( [map] (tel: 0141-287 3050; Mon–Sat 10am–5pm, Thu until 8pm, Sun 11am–5pm; free). The glorious building in which it is housed began life as the 18th-century mansion of a tobacco lord, and has since been a bank, the Royal Exchange, and more recently a public library and extensive archive. Today all aspects of modern art, from painting, sculpture, photography and video installations, by both Scottish and international artists, are housed on four floors.

Among the city centre’s most distinguished Georgian buildings are Hutcheson’s Hall, in Ingram Street (currently closed to the public), designed by David Hamilton; and, in nearby Glassford Street, Trades Hall , [map] , which, despite alterations, has retained the facade designed by the great Robert Adam.

But any excursion around Glasgow’s architectural treasures must include the work of the city’s most innovative genius, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, who overturned the Victorians in a series of brilliant designs between 1893 and 1911. Mackintosh’s influence on 20th-century architecture, along with his leading contribution to Art Nouveau in interiors, furniture and textile design, has long been acknowledged and celebrated throughout Europe, although all his finest work was done in and around Glasgow.

Mackintosh favourites

Mackintosh’s sometimes austere, sometimes sensuous style, much influenced by natural forms and an inspired use of space and light, can be seen in several important buildings: his greatest achievement, designed in 1896, the Glasgow School of Art ⁄ [map] (tel: 0141-353 4526; www.gsa.ac.uk; guided tours Apr–Sept daily 11am–5pm on the hour, Oct–Mar Mon–Sat 11.30am and 2.30pm; advance booking advisable) in Renfrew Street is not only one of Britain’s most esteemed art schools but is considered by many to be the designer’s masterpiece. Scotland Street School, on the South Side, opened in 1904 and is now a Museum of Education (tel: 0141-287 0500; Mon–Thu, Sat 10am–5pm, Fri, Sun 11am–5pm free) detailing experiences of Glasgow schoolchildren throughout the 20th century, including re-created classrooms. The Martyrs’ Public School (tel: 0141-946 6600; currently closed to the public), perched above a slip road to the M8 motorway near Glasgow Cathedral houses Glasgow Museum’s Conservation Department.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh design.

Mockford & Bonetti/Apa Publications

In Sauchiehall Street, the facade of the Mackintosh-designed Willow Tea Rooms ¤ [map] (1903) remains, and a room on the first floor has been turned over to teatime again, with reproduction Mackintosh furniture. But more stunning examples of his interior designs can be seen at the Mackintosh House at the University of Glasgow’s Hunterian Art Gallery ‹ [map] (tel: 0141 330 4221; www.gla.ac.uk/hunterian; Tue–Sat 10am–5pm, Sun 11am–4pm; gallery free) on Gilmorehill. There, rooms from the architect’s own house have been reconstructed and exquisitely furnished with original pieces of his furniture, watercolours and designs.

Dining room in the House for an Art Lover.

Mockford & Bonetti/Apa Publications

Also worth a visit are the House for an Art Lover (tel: 0141-353 4770; www.houseforanartlover.co.uk; times vary, check first) in Bellahouston Park, erected long after his death, but to his exact specifications; the Queen’s Cross Church (tel: 0141-946 6600; Apr–Oct Mon, Wed, Fri 10am–5pm, Nov–Mar until 4pm) – now often referred to simply as The Mackintosh Church – in Garscube Road; and The Lighthouse (tel: 0141-276 536; www.thelighthouse.co.uk; Mon–Sat 10.30am–5pm, Sun noon–5pm) in Mitchell Lane near Central Station, now a Mackintosh study centre as well as a broad-based architecture and design centre.

There’s not much left in Glasgow that is old by British standards. The oldest building is Glasgow Cathedral › [map] (tel: 0141-552 8198; Mon–Sat 9.30am–5.30pm, Sun 1–5pm, Oct–Mar until 4pm; free), most of which was completed in the 13th century, though parts were built a century earlier by Bishop Jocelyn. It was completed by the first bishop of Glasgow, Robert Blacader (1483–1508) and includes stunning stained-glass windows. The only pre-Reformation dwelling house is Provand’s Lordship (tel: 0141 276 1625; Tue–Thu, Sat 10am–5pm, Fri, Sun 11am–5pm; free), built in 1471 as part of a refuge for poor people and extended in 1670. It was preserved by William Burrell at the turn of the 20th century and now contains a museum of medieval material. Behind it is a Physic Garden, with a soothing array of herbs, and an orchard.

Both old buildings stand on Cathedral Street, at the top of the High Street – the cathedral on a site that has been a place of Christian worship since it was blessed for burial in AD 397 by St Ninian, the earliest missionary recorded in Scottish history. A severe but satisfying example of early Gothic, it contains the tomb of St Mungo.

Behind the cathedral, overseeing the city from the advantage of height, are more tombs – the intimidating Victorian sepulchres of the Western Necropolis (7am–dusk; free). This cemetery, modelled on Père Lachaise in Paris and intended to be a class-free interdenominational resting place, is a tribute to how important 19th-century society considered the rituals of burial. Many of the tombs, mausoleums and memorials are elaborately carved with statuary and symbolic motifs. It is all ‘supervised’ by a statue of John Knox, the 16th-century reformer, and among the ranks of Glaswegian notables buried here is one William Miller, ‘the laureate of the nursery’, who wrote the popular bedtime jingle, ‘Wee Willie Winkie’. In addition, on a clear day there are wonderful views of the city and surrounding countryside from here, including, in particularly fine weather, as far as Loch Lomond, so it’s worth a visit even if roaming around headstones doesn’t appeal.

A cream-coloured Scottish baronial building in front of the cathedral is home to the St Mungo Museum of Religious Life and Art (tel: 0141-276 1625; Tue–Thu, Sat 10am–5pm, Fri, Sun 11am–5pm; free), named after the city’s patron saint and dedicated to the exploration of the six main world religions (Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, Christianity, Buddhism and Sikhism). There is also a Japanese Zen garden and some lovely stained-glass windows. Don’t miss the comments on the visitors’ board, either.

The two oldest churches in Glasgow, other than the cathedral, are St Andrew’s In the Square fi [map] , which contains some spectacular plasterwork, and the Episcopal St Andrew’s-by-the-Green fl [map] , once known as the Whistlin’ Kirk because of its early organ. Both were built in the mid-18th century and both can be found to the northwest of Glasgow Green, in the Merchant City.

Tomb of St Mungo in the crypt of Glasgow Cathedral.

Mockford & Bonetti/Apa Publications

17th-century steeples

In the Merchant City you will also find two remnants of the 17th century, the Tolbooth Steeple ‡ [map] and the Tron Steeple ° [map] . The Tolbooth Steeple at Glasgow Cross (where the Mercat Cross is a 20th-century replica of a vanished one) is a pretty substantial remnant of the old jail and courthouses, being seven storeys high with a crown tower. The Tron Steeple was once attached to the Tron Church, at the Trongate, and dates back to the late 16th and early 17th centuries. The original church was burned down in the 18th century and the replacement now accommodates the lively Tron Theatre. Just to the west is Trongate 103, an art resource venue and centre of artistic creativity housed over six storeys.

Fact

Scottish poet and author Tobias Smollett, writing in 1771, had no doubts about Glasgow’s standing as a commercial centre: ‘One of the most flourishing in Great Britain…it is a perfect bee-hive in point of industry.’

Markets

Heavy industry has come and gone, but Glasgow still flourishes as a city of independent enterprise – of hawkers, stallholders, street traders and marketeers. Even the dignified buildings of its old, more respectable markets – fish, fruit and cheese – have survived in a city that has often been careless with its past, and have now become part of the rediscovery of the Merchant City area, which stretches from the High Street and the Saltmarket in the east to Union Street and Jamaica Street in the west. It contains most of the city’s remaining pre-Victorian buildings.

East entrance to Barras weekend market.

Mockford & Bonetti/Apa Publications

The old Fishmarket · [map] in Clyde Street is in fact Victorian, but it accommodates a perpendicular remnant of the 17th-century Merchants’ House that was demolished in 1817. Known as the Briggait, a corruption of Bridgegate, it is now home to the Wasps Artists’ Studios. (The genuine fish market is now out of town off the M8 motorway.)

In Candleriggs º [map] , slightly to the north and so-named because at one time candlemakers traded here, the old fruitmarket now houses a variety of cafés, restaurants and shops, while Glasgow’s market celebrity still belongs to the Barras ¡ [map] (Sat, Sun 10am–5pm), a thriving flea market in the Gallowgate to the east, where both repartee and bargains were once reputed to rival those of Paris’s flea market and London’s Petticoat Lane. Founding queen of the Barras was Mrs McIver, who started her career with one barrow, bought several more to hire out on the piece of ground she rented in the Gallowgate, and was claimed to have retired a millionaire. A mixture of genuine vintage and genuine junk, it’s heaven for any bargain hunter who enjoys a good rummage. Nearby is the Glasgow Antiques Market (tel: 0141-552 6989; Sat–Sun 9am–5pm), which is the place to go for more serious and more moneyed collectors. Also nearby is Barrowland Ballroom, one of the city’s most thriving live-music venues for the past few decades. Its fame briefly turned to infamy, however, in the 1960s when a serial killer known as Bible John murdered three women whilst quoting passages from the Good Book.

Pavement cafes on Byres Road in the West End.

Mockford & Bonetti/Apa Publications

Argyle Street, traversed by the railway bridge to Central Station, Sauchiehall Street and the more up-market Buchanan Street, with the Buchanan Galleries complex, are Glasgow’s great shopping thoroughfares, while the cosmopolitan café culture area round Great Western Road and Byres Road, in the West End, is a centre for interesting bric-a-brac and boutiques. Ruthven Lane is the place to go for vintage finds. West Regent Street has a Victorian Village (small antique shops in old business premises) and the area around the Italian Centre in the Merchant City is alive with stylish café-bars.

Glaswegians have always spent freely, belying the slur on the open-handedness of Scots, and the city’s commercial interests seem to believe that the appetite for shopping is insatiable. Just off Buchanan Street, up-market Princes Square Shopping Centre ™ [map] (www.princessquare.co.uk), with a range of high-end high street outlets and a number of cafés and bars, is worth visiting even for those who don’t wish to shop or eat. It’s also a welcome respite from the rain, which is no rare occurrence in Glasgow.

The site of the demolished St Enoch Railway Station and hotel (one of Glasgow’s major acts of vandalism) is now occupied by the St Enoch Centre # [map] (www.st-enoch.co.uk) a spectacular glass-covered complex of shops, a fast-food court, ice rink and car park. A popular leisure and retail development is the huge waterside Braehead Centre (www.intu.co.uk/braehead), at Renfrew on the western edge of the city.

‘Edinburgh is the capital,’ as the old joke goes, ‘but Glasgow has the capital.’ And it flaunts it.