The ink was hardly dry on the Treaty of Union of 1707 when the Scots began to smart under the new constitutional arrangements. The idea of a union with England had never been popular with the working classes, most of whom saw it (rightly) as a sell-out by the aristocracy to the ‘Auld Enemy’. Scotland’s businessmen were outraged by the imposition of hefty, English-style excise duties on many goods and the high-handed government bureaucracy that went with them. The aristocracy who had supported the Union resented Westminster’s peremptory abolition of Scotland’s Privy Council. Even the hardline Cameronians – the fiercest of Protestants – roundly disliked the Union in the early years of the 18th century.

Prince Charles in his finery as the Young Chevalier, c.1740.

Hulton Picture Library

All of which was compounded by the Jacobitism (support for the Stuarts) that haunted many parts of Scotland, particularly among the Episcopalians of Aberdeenshire, Angus and Perthshire, and among the Catholic clans (such as the MacDonalds) of the Western Highlands.

Jacobite insurgency

Given that one of the main planks of Jacobitism was the repeal of the Union, it was hardly surprising that the Stuart kings cast a long shadow over Scotland in the first half of the 18th century. In fact, within a year of the Treaty of Union being signed, the first Jacobite insurgency was under way, helped by a French regime ever anxious to discomfit the power of the English.

Oil painting of Prince Charles Edward Stuart in Edinburgh in 1745, by William Brassey Hole.

Bridgeman Art Library

In January 1708 a flotilla of French privateers commanded by Comte Claude de Forbin battered its way through the North Sea gales, carrying the 19-year-old James Stuart, the self-styled James VIII and III. After a brief sojourn in the Firth of Forth near the coast of Fife, the French privateers were chased round the top of Scotland and out into the Atlantic by English warships. Many of the French vessels foundered on their way back to France, although James survived to go on plotting.

On dry land, the uprising of 1708 was confined to a few East Stirlingshire lairds who marched around with a handful of men. They were quickly rounded up, and that November five of the ringleaders were tried in Edinburgh for treason. The verdict on all five was ‘not proven’ and they were freed. Shocked by this display of Scottish leniency, the British parliament passed the Treason Act of 1708, which brought Scotland into line with England, ensuring traitors a gruesome death.

Bealach-n-Spainnteach (the Pass of the Spaniards), a niche in the Kintail Mountains, recalls the defeat of the Spanish when they joined forces with the Jacobites in 1719 and were swiftly routed by the British.

Bobbing John v. Red John

The next Jacobite uprising, in 1715, was a serious affair. By then disaffection in Scotland with the Union was widespread, the Hanoverians had not secured their grip on Britain, there were loud pro-Stuart mutterings in England, and much of Britain had been stripped of its military.

But the insurrection was led by the Earl of Mar, a military incompetent known as ‘Bobbing John’, whose support came mainly from the clans of the Central and Eastern Highlands. When the two sides clashed at Sheriffmuir near Stirling on 13 November, Mar’s Jacobite army had a four-to-one advantage over the tiny Hanoverian force commanded by ‘Red John of the Battles’ (as the duke of Argyll was known). But, instead of pressing his huge advantage, Mar withdrew his Highland army after an inconclusive clash.

Culloden’s victor, the Duke of Cumberland.

Hulton Picture Library

The insurrection of 1715 quickly ran out of steam. The Pretender himself (or the Old Pretender – James Stuart) did not arrive in Scotland until the end of December, and the forces he brought with him were too little and too late. He did his cause no good by stealing away at night (along with ‘Bobbing John’ and a few others), leaving his followers to the wrath of the Whigs. The duke of Argyll was sacked as commander of the government forces for fear he would be too lenient. Dozens of rebels – especially the English – were hanged, drawn and quartered, and hundreds were deported.

Not that the debacle of 1715 stopped the Stuarts trying again. In 1719 it was the Spaniards who decided to try to shake the Hanoverian pitch by backing the Jacobites. Again it was a fiasco. In March 1719 a little force of 307 Spanish soldiers sailed into Loch Alsh where they joined up with a few hundred Murrays, Mackenzies and Mackintoshes. This Spanish-Jacobite army was easily routed in the steep pass of Glenshiel by a British unit, which swooped down from Inverness to pound the Jacobite positions with their mortars. The Highlanders simply vanished into the mist and snow of Kintail, leaving the wretched Spaniards in their gold-on-white uniforms to wander about the subarctic landscape before surrendering.

Prince Charlie’s much romanticised farewell to Flora MacDonald in 1746.

Hulton Picture Library

The Young Pretender

But it was the insurrection of 1745, ‘so glorious an enterprise’, led by Charles Edward Stuart (Bonnie Prince Charlie or the Young Pretender), which shook Britain, despite the fact that the government’s grip on the turbulent parts of Scotland had never seemed firmer. There were military depots at Fort William, Fort Augustus and Fort George, and an effective Highland militia (later known as the Black Watch) had been raised. General Wade had thrown a network of military roads and bridges across the Highlands. Logically, Charles, the Young Pretender, should never have been allowed to set foot out of the Highlands.

But having set up a military ‘infrastructure’ in the Highlands, the British Government had neglected it. The Independent Companies (the Black Watch) had been shunted out to the West Indies, there were fewer than 4,000 troops in the whole of Scotland, hardly any cavalry or artillery, and Clan Campbell was no longer an effective fighting force. The result was that Bonnie Prince Charlie and his ragtag army of MacDonalds, Camerons, Mackintoshes, Robertsons, McGregors, Macphersons and Gordons, plus some Lowland cavalry and a stiffening of Franco-Irish mercenaries, was able to walk into Edinburgh and set up a ‘royal court’ in Holyrood Palace.

In that September the Young Pretender sallied out of Edinburgh and wrecked General John Cope’s panicky Hanoverian army near Prestonpans, and then marched across the border into England. But Stuart’s success was an illusion. There was precious little support for his cause in the Lowlands of Scotland. Few Jacobite troops had been raised in Edinburgh, and Glasgow and the southwest were openly hostile. Some men had been drummed up in Manchester, but there was no serious support from the Roman Catholic families of northern England. Charles got as far as Derby and then fled back to Scotland with two powerful Hanoverian armies hot on his heels.

Culloden Cairn.

David Cruickshanks/Apa Publications

Battle of Culloden

After winning a rearguard action at Clifton, near Penrith, and what has been described as a ‘lucky victory’ at Falkirk in January 1746, the Jacobite army was cut to pieces by the duke of Cumberland’s artillery on Drummossie Moor, Culloden, near Inverness on 16 April 1746. It was the last great pitched battle on the soil of mainland Britain.

It was also the end of the Gaelic clan system, which had survived in the mountains of Scotland long after it had disappeared from Ireland. The days when an upland chieftain could drum up a ‘tail’ of trained swordsmen for cattle raids into the Lowlands were over.

Following his post-Culloden ‘flight across the heather’, Charles, disguised as a woman servant, was given shelter on the Isle of Skye by Flora MacDonald, thus giving birth to one of Scotland’s abiding romantic tales. He was then plucked off the Scottish coast by a French privateer and taken into exile, drunkenness and despair in France and Italy. A few dozen of the more prominent Jacobites were hauled off to Carlisle and Newcastle where they were tried, and some hanged. And for some time the Highlands were harried mercilessly by the duke of Cumberland’s troopers.

In an effort to subdue the Highlands, the government in London passed the Disarming Act of 1746, which not only banned the carrying of claymores, targes, dirks and muskets, but also the wearing of tartans and the playing of bagpipes. It was a nasty piece of legislation, which impacted greatly on Gaelic culture. The British Government also took the opportunity to abolish Scotland’s inefficient and often corrupt system of ‘Courts of Regality’ by which the aristocracy (and not just the Highland variety) dispensed justice, collected fines and wielded powers of life and wealth.

A Skye crofter prepares some winter comfort.

Mary Evans Picture Library

The Age of Enlightenment

It is one of the minor paradoxes of 18th-century European history that, while Scotland was being racked by dynastic convulsions, which were 17th-century in origin, the country was transforming itself into one of the most forward-looking societies in the world. Scotland began to wake up in the first half of the 18th century. By about 1740 the intellectual, scientific and mercantile phenomenon that became known as the Scottish Enlightenment was well under way, although it didn’t reach its peak until the end of the century.

Whatever created it, the Scottish Enlightenment was an extraordinary explosion of creativity and energy. And while, in retrospect at least, the period was dominated by David Hume, the philosopher, and Adam Smith, the economist, there were many others, such as William Robertson, Adam Ferguson, William Cullen and the Adam brothers. Through the multifaceted talents of its literati, Scotland in general and Edinburgh in particular became one of the intellectual powerhouses of Western Europe.

The Clearances

But the Enlightenment and all that went with it had some woeful side effects. The Highland ‘Clearances’ of the late 18th and early 19th centuries owed much to the ‘improving’ attitudes triggered by the Enlightenment, as well as the greed of the lairds. It was realised that, while the Highlands were capable of producing from £200,000 to £300,000 worth of black cattle every year, the land would produce double the amount of mutton, with the additional benefit of wool.

The argument proved irresistible. Sheep – particularly Cheviots – and their Lowland shepherds began to flood into the glens and straths of the Highlands, displacing the Highland ‘tacksmen’ and their families. Tens of thousands were forced to move to the Lowlands, coastal areas, or the colonies overseas, taking with them their culture of songs and traditions.

The worst of the Clearances – or at least the most notorious – took place on the huge estates of the countess of Sutherland and her rich, English-born husband, the marquis of Stafford. Although Stafford spent huge sums of money building roads, harbours and fish-curing sheds (for very little profit), his estate managers evicted tenants with real ruthlessness. It was a pattern that was repeated all over the Highlands at the beginning of the 19th century, and again later when people were displaced by the red deer of the ‘sporting’ estates. The overgrown remains of villages are a painful reminder of this sad chapter in Scottish history.

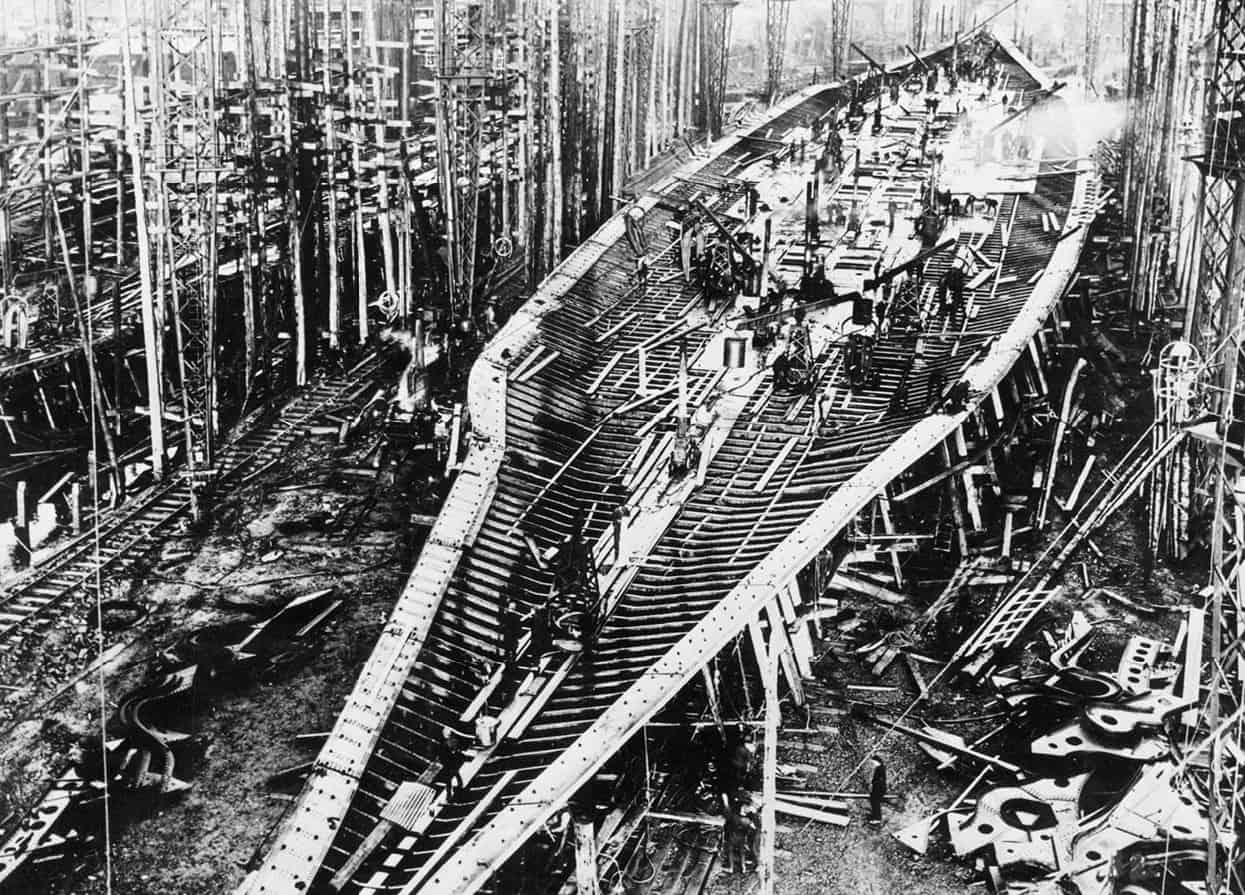

Glasgow in the 18th century.

Mary Evans Picture Library

Radicals and reactionaries

As the industrial economy of Lowland Scotland burgeoned at the end of the 18th century, it sucked in thousands of immigrant workers from all over Scotland and Ireland. The clamour for democracy grew. Some of it was fuelled by the ideas of the American and French revolutions, but much of the unrest was a reaction to Scotland’s hopelessly inadequate electoral system. At the end of the 18th century, there were only 4,500 voters in the whole of Scotland and only 2,600 voters in the 33 rural counties.

And for almost 40 years Scotland was dominated by the powerful machine politician Henry Dundas, the first viscount Melville, universally known as ‘King Harry the Ninth’.

As solicitor general for Scotland, lord advocate, home secretary, secretary for war and then first lord of the Admiralty, Dundas wielded awesome power.

Industrial glory

The Enlightenment was not just confined to the salons of Edinburgh. Commerce and industry also thrived. ‘The same age, which produces great philosophers and politicians, renowned generals and poets, usually abounds with skilled weavers and ship-carpenters,’ the Scottish philosopher David Hume wrote in 1752.

By 1760 the famous Carron Ironworks in Falkirk was churning out high-grade ordnance for the British military and by 1780 hundreds of tons of goods on barges were being shuttled between Edinburgh and Glasgow along the Forth–Clyde Canal.

The Turnpike Act of 1751 improved the road system dramatically and created a brisk demand for carriages and stagecoaches. In 1738 Scotland’s share of the tobacco trade (based in Glasgow) was 10 percent; by 1769 it was more than 52 percent.

There was also a huge upsurge of activity in many trades such as carpet-weaving, upholstery, glassmaking, china and pottery manufacture, linen, soap, distilling and brewing.

The 18th century changed Scotland from one of the poorest countries in Europe to a state of middling affluence. It has been calculated that between 1700 and 1800, the money generated within Scotland increased by a factor of more than 50, while the population stayed more or less static (at around 1.5 million).

But nothing could stop the spread of libertarian ideas in an increasingly industrialised workforce. The ideas contained in Tom Paine’s Rights of Man spread like wildfire in the Scotland of the 1790s. The cobblers, weavers and spinners proved the most vociferous democrats, but there was also unrest among farmworkers, and among seamen and soldiers in the Highland regiments.

Throughout the 1790s a number of radical ‘one man, one vote’ organisations sprang up, such as the Scottish Friends of the People and the United Scotsmen (a quasi-nationalist group that modelled itself on the United Irishmen led by Wolfe Tone).

But the brooding figure of Dundas was more than a match for the radicals. Every organisation that raised its head was swiftly infiltrated by police spies and agent provocateurs. Ringleaders (such as the advocate Thomas Muir) were framed, arrested, tried and deported. Some, such as Robert Watt, who led the ‘Pike Plot’ of 1794, were hanged. Meetings were broken up by dragoons, riots were put down by musket fire and the Scottish universities were racked by witch-hunts.

Although Dundas himself was discredited in 1806, after being impeached for embezzlement, and died in 1811, the anti-radical paranoia of the Scottish ruling class lingered on. Establishment panic peaked in 1820 when the so-called Scottish Insurrection was brought to an end in the legally corrupt trial of the weavers James Wilson, John Baird, Andrew Hardie and 21 other workmen. A special (English) Court of Oyer and Terminer was set up in Glasgow to hear the case, and Wilson, Baird and Hardie were sentenced to a gruesome execution, after making resounding speeches. The other radicals were sentenced to penal transportation.

Lord Cockburn summed up the relentless grip of the powerful Henry Dundas, also known as ‘King Harry the Ninth’, on Scotland: ‘Who steered upon him was safe; who disregarded his light was wrecked.’

Reform and disruption

By the 1820s most of Scotland (and indeed Britain) was weary of the political and constitutional corruption under which the country laboured. In 1823 Lord Archibald Hamilton pointed out the electoral absurdity of rural Scotland: ‘I have the right to vote in five counties in Scotland, in not one of which do I possess an acre of land,’ he said, ‘and I have no doubt that if I took the trouble I might have a vote for every county in that kingdom.’ Hamilton’s motion calling for parliamentary reform was defeated by only 35 votes.

But nine years later, in 1832, the Reform Bill finally passed into law, giving Scotland 30 rural constituencies, 23 burgh constituencies and a voting population of 65,000 (compared to a previous 4,500). Even this limited extension of the franchise – to male householders whose property had a rentable value of £10 or more – generated much wailing and gnashing of teeth among Scottish Tories.

No sooner had the controversy over electoral reform subsided than it was replaced by the row between the ‘moderates’ and the ‘evangelicals’ within the Church of Scotland. ‘Scotland,’ Lord Palmerston noted at the time, ‘is aflame about the Church question.’ But this was no genteel falling-out among theologians. It was a brutal and bruising affair, which dominated political life in Scotland for 10 years and raised all kinds of constitutional questions.

At the heart of the argument was the Patronage Act of 1712, which gave Scots lairds the same right English squires had to appoint, or ‘intrude’ clergy on local congregations. Ever since it was passed, the Church of Scotland had justifiably argued that the Patronage Act was a flagrant and illegal violation of the Revolution Settlement of 1690 and the Treaty of Union of 1707, both of which guaranteed the independence of the Church of Scotland.

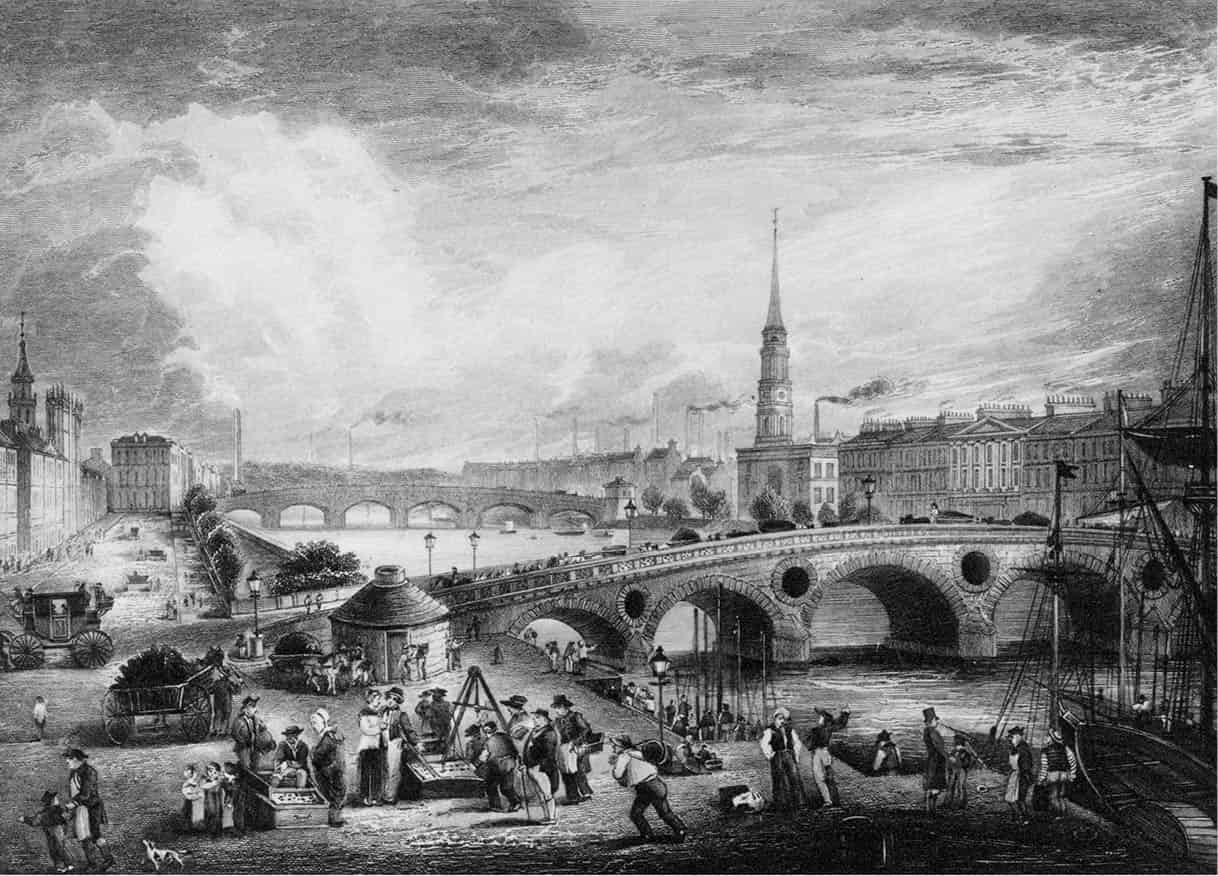

Broomielaw Bridge, Carlton Place and Clyde Street in Glasgow, 1830.

Bridgeman Art Library

A free church

But the pleas fell on deaf ears. The English-dominated parliament could see no fault in a system that enabled Anglicised landowners to appoint like-minded clergymen. Patronage was seen by the Anglo-Scottish establishment as a useful instrument of political control and social progress. The issue came to a head in May 1843 when the evangelicals, led by Dr Thomas Chalmers, marched out of the annual General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in Edinburgh to form the Free Church of Scotland.

Chalmers, theologian, astronomer and brilliant organiser, defended the Free Church against bitter enemies. His final triumph, in 1847, was to persuade the London parliament that it was a folly to allow the aristocracy to refuse the Free Church land on which to build churches and schools. A few days after he had given evidence, Chalmers died in Edinburgh.

The rebellion of the evangelicals was brilliantly planned, well funded and took the British establishment completely by surprise: 400 teachers left the kirk and, within 10 years of the Disruption, the Free Church had built more than 800 churches, 700 manses, three large theological colleges and 600 schools, and brought about a huge extension of education.

After 1847, state aid had to be given to the Free as well as to the established Church schools, and in 1861 the established Church lost its legal powers over Scotland’s parish school system. This prepared the ground for the Education Act of 1872, which set up a national system under the Scottish Educational Department. And, although it ran into some vicious opposition from landowners, especially in the Highlands, the Free Church prevailed.

Scottish Presbyterians in the 17th century defying the law to worship.

Mary Evans Picture Library

In fact, it can be argued that the Disruption was the only rebellion in 18th- or 19th-century British history that succeeded. Chalmers and his supporters had challenged both the pervasive influence of the Anglo-Scottish aristocracy and the power of the British Parliament, and they had won. The Patronage Act of 1712 was finally repealed in 1874, and the Free Church merged back with the Church of Scotland in 1929, uniting the majority of Scottish Presbyterians in one Church.