When Lincoln reached the conclusion that McClellan was not the man to bring the war to an end, he turned to a fellow native of Kentucky – John Pope. Pope, like Lincoln, had left this state and relocated to Illinois, and it was from here that he received an appointment to the United States Military Academy. After graduation in 1842, his class standing (17 out of 56) was high enough to secure a posting to the prestigious Corps of Topographical Engineers.

Pope eventually ended up apparently trapped in the backwater of Maine, but he was rescued by the outbreak of the Mexican War in 1846. His service and valor in this conflict earned him promotion to brevet captain.

By 1 July 1856 Pope had advanced to a captaincy in the Topographical Engineers, a rank he held until 14 June 1861. On that day, having had the good fortune to serve as an escort officer accompanying Lincoln to the inauguration, and because of other ties to the new chief executive, he was advanced to a brigadier of volunteers. During the next year he held various commands in Missouri, serving under John C. Frémont. His performance was such that he ultimately was put in charge of operations along the Mississippi River.

By early 1862, after victories at New Madrid and the Mississippi River’s Island No. 10, he was made commander of one of the three field armies led by Henry W. Halleck toward Corinth, Mississippi. He soon added a second star to his shoulder straps when he was appointed a major general of US Volunteers on 21 March 1862. All this put him in line for consideration when Lincoln decided to combine the three divided Union commands in northern Virginia, which had all failed to bring Jackson to bay in the Shenandoah Valley.

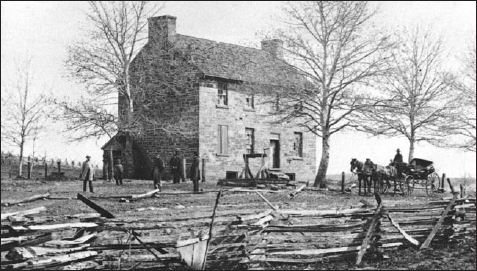

During July 1861, at the Battle of First Manassas, Jackson made “Portici” his headquarters. Over 12 months later, the din of muskets and cannon could again be heard in the vicinity of this stately home. LC

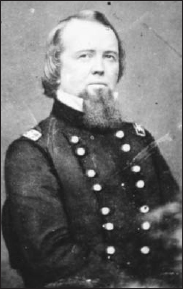

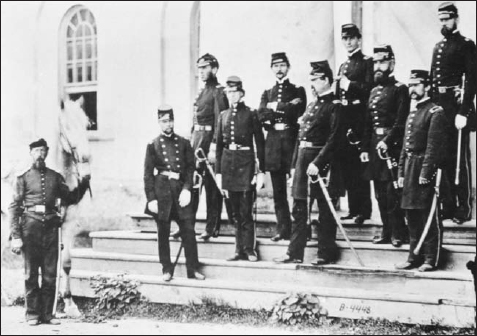

Major General George B. McClellan (center) had been hailed as the man who would bring swift victory for the North. “Little Mac” did not live up to expectations, although he continued to command the Army of the Potomac after he failed to capture Richmond. Many other generals in this group portrait would serve at the Battle of Second Bull Run. NA

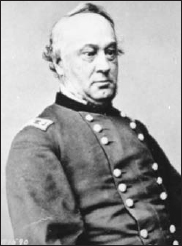

Known as “Old Brains” Major General Henry Wagner Halleck assumed duties as general-in-chief of the Union Army during the summer of 1862. He was a good administrator, but lacked strategic capabilities and the strong leadership needed to direct his fellow Union generals during the campaign that brought the Northern and Southern armies back to Bull Run. NA

With the disparate corps combined into the Army of Virginia, Pope took charge of the organization on 26 June 1862. Frémont would not serve under his former subordinate, and was replaced by another officer. He was not the only one to disdain Pope, who became unpopular with many of his fellow officers, as well as the rank and file. This bad feeling could be traced to the early days of Pope’s command of the Army of Virginia. He issued a pompous communiqué to his new command boasting: “Let us understand each other. I have come to you from the West, where we have always seen the backs of our enemies; whose business it has been to seek the adversary, and to best him where he was found; whose policy had been attack and not defense.” Not only did these words grate with McClellan and his supporters, but they also raised the hackles of the troops in the Army of Virginia, many of whom had been serving in the theater for some time and resented being portrayed as ineffective or even worse, cowardly!

In another unfortunate piece of bombast, Pope claimed his headquarters would be in the saddle. This boast backfired with several of Pope’s peers maintaining he had his “headquarters where his hindquarters” ought to be.

Lincoln unilaterally selected Pope as a “western man” who could prosecute the war, but his choice of champion did more than antagonize the forces of the eastern theater, however. Pope became a target for particular hatred in the South by prescribing harsh treatment of Confederate sympathizers. Virginians in areas controlled by his troops were to be brought in and instructed to take the oath of allegiance to the United States. If they balked, they were to be turned out from their homes and expelled to enemy territory. Additionally, not only did he order his troops to live off the land, but also directed that guerrillas were to be executed as traitors when captured. Furthermore, five local civilians of prominence were to be rounded up and put to death if partisans shot at his men.

Disappointed with McClellan’s performance, President Abraham Lincoln cast about for a new head for his army. He now pinned his hopes on John Pope, who despite much bravado was no match for the opposition he encountered at Second Bull Run. Pope’s shortcomings proved costly, opening the way for the Confederates to bring the war north. NA

In this foretaste of the total war concept practised so effectively later by Ulysses Grant, Pope provoked the usually mild-mannered Lee in a way that no other adversary ever had. Lee developed a personal enmity toward Pope, referring to him as a “miscreant” who had to be “suppressed.”

In response, the Confederate government made it known that Pope and his officers would not be accorded consideration as soldiers. If caught they would be held prisoner so long as Pope’s odious dictates remained in effect. Should Southern civilians be killed, a like number of Federal prisoners would be sent to the gallows.

These harsh measures were not carried out and after the Second Manassas campaign the point became moot. In fact, at that time Lincoln also lost faith in his protégé and shortly after Pope’s defeat in northern Virginia he was transferred.

For most of the remainder of the war Pope oversaw the Department of the Northwest, and among other things dealt with the 1864 Sioux uprising in Minnesota. Having redeemed himself in the eyes of the administration, in 1865 he received a brevet as a regular army major general in recognition of his actions at Island No.10. The following year he mustered out of the volunteers, but returned to the regulars where he served as departmental commander in various locations until his retirement in 1886. Six years later he died.

At the same time that Lincoln was looking for an alternative to McClellan as his eastern field commander, he was also seeking to replace McClellan as general-in-chief. On 11 July 1862 Henry Halleck, a New York native and Military Academy graduate (1839), was given the mantel previously worn by Winfield Scott and George McClellan.

An engineer officer who had been breveted for his performance in Mexico, Halleck previously had overseen construction of coastal fortifications, served as a member of the faculty at West Point, and conducted a study of France’s military. These endeavors and his writings Report on the Means of National Defense and Elements of Military Art and Science, along with a translation of the influential French volume Vie Politique et Militaire de Napoleon by Henri Jomini, earned him the nickname of “Old Brains” but this sobriquet became derogatory during the Civil War.

Major General Irvin McDowell had commanded at First Bull Run, but his reputation suffered greatly as the Union Army left the field in disarray. During the summer of 1862 McDowell, seen here (center) with his staff, was to return to the scene of this earlier Federal defeat. NA

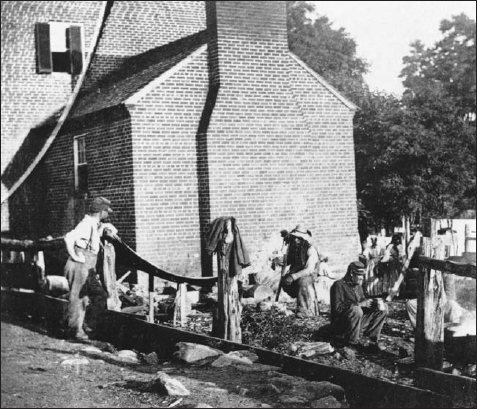

During both battles at Manassas, Henry P. Matthew’s solid stone house on the Warrenton Turnpike would be pressed into service as a hospital. USAMHI

In 1852 Franz Sigel journeyed from his native Baden in Germany to the United States. He was outspoken and held liberal views, leading him to support the unsuccessful Revolution of 1848 against Prussia. The former army officer fled his native land, which brought him to St. Louis, Missouri. His influence among the German community led to him being commissioned as a brigadier general of volunteers soon after the Civil War began. NA

Although Halleck had left the army in 1854 to establish a law practice in California, he continued his interest in the profession of arms. When the war broke out, Winfield Scott recommended Halleck be given an important assignment, and as such, on 19 August 1861, he was commissioned a major general in the US Army.

After modest accomplishments in the western theater of operations he was called to Washington, where it was believed his administrative capabilities would bear fruit in galvanizing the Union army into a viable force. This was not to prove the case, however, and a number of his subordinates criticized him for a failure to clearly communicate both what was expected of them and the actions of the various commands. To some degree both of these characteristics were evident during the Second Manassas campaign.

Furthermore, Halleck tended to attribute failures to others, thereby alienating most of his fellow generals. Consequently, he was finally reassigned as the army’s chief of staff, and in this role performed well, although he remained one of the most unpopular men in Washington.

At war’s end he remained in uniform, first as commander in Virginia and later as head of the Military Division of the Pacific. In 1872 he died while serving in Louisville, Kentucky.

Massachusetts governor “Bobbin Boy” Banks, who had been speaker of the state’s lower house, and for a time one of its US congressmen, was just one of many political appointees to be named a general in the Union volunteers. With no military background, he remained in divisional and departmental commands near the capital during the early stages of the war, but was then sent to the Shenandoah Valley. The Confederates under Stonewall Jackson outfought the politician-turned-soldier, and after capturing a significant cache of his supplies jokingly referred to him as “Commissary Banks”.

Massachusetts governor Nathaniel P. “Bobbin Boy” Banks was just one of many political appointees to be named a general in the Union volunteers. Lacking a military background, he remained in divisional and departmental commands near the capital during the early stages of the war, but by the time of Second Manassas was II Corps commander in the Army of Virginia.

Not long after Banks was assigned to the Army of Virginia, Jackson goaded him again at Cedar Mountain, then once more faced him at Second Manassas. After a short assignment in Washington, the administration shipped him to New Orleans as Benjamin F. “Beast” Butler’s replacement. In that command Port Hudson was his first target, but he failed to overcome the defenses until after Vicksburg had been taken by Grant.

His effectiveness during the Red River Campaign of 1864 was little better. Despite such lackluster martial performances, Congress decided to honor him with a resolution of thanks. Banks mustered out of the volunteers on 24 August 1865 and returned to politics.

As a young man Irvin McDowell attended the Collège de Troyes in France, then went on to the US Military Academy where he graduated 23rd of 45 cadets in his class of 1838. He was commissioned in the artillery, with a stint of frontier duty before returning to West Point as a tactics instructor and adjutant.

During the Mexican War he became General John Wool’s aide de camp and adjutant, followed by another posting to the frontier. He ultimately secured a transfer to army headquarters in Washington. While serving there, Winfield Scott introduced him to a number of influential members of Lincoln’s administration. Secretary of the Treasury Samuel Chase particularly championed his cause and was instrumental in obtaining Major McDowell a promotion to brigadier general in the Regular Army on 14 May 1861. Two weeks later he assumed command of forces south of the Potomac and in the vicinity of the capital.

McDowell was not to remain encamped for long, however. Political pressures and the short term of enlistment of some of his troops, forced him to lead his unprepared army to Manassas. Part of his command marched against Blackburn’s Ford along Bull Run. A few days later McDowell launched his main attack, which resulted in the First Battle of Manassas (Bull Run). The failure of Union arms at First Manassas brought an end to his rapid rise. Four days after this defeat, McClellan assumed control, while on 3 October McDowell was assigned a division. After the Army of the Potomac was organized, he gained a better berth, being entrusted with I Corps. His first assignment was the protection of Washington as McClellan began the Peninsula Campaign. In due course his men were to proceed overland to support McClellan in his drive against Richmond, but as events transpired McDowell and his men were diverted to face Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley.

Following this unsuccessful effort, he was assigned III Corps in Pope’s Army of Virginia. In that capacity he participated in the actions at Cedar Mountain and Rappahannock Station. Several years later the former engagement gained him a major-general’s brevet in the Regular Army.

In the wake of Second Manassas he was relieved from his command, being singled out as one of the parties responsible for the Union defeat. He requested a court of inquiry, and was absolved of blame for the débâcle; a fate not shared by fellow Union general Fitz John Porter, who became the scapegoat for the loss, not clearing his name until many years after the war.

South Carolinian James Longstreet began his military career as a cadet at West Point, graduating in 1842. Commissioned as a second lieutenant in the infantry, he served in the Mexican War where he was wounded at Chapultepec. He subsequently became a major in the US Army Paymaster Department. On 1 June 1861, Longstreet, who would come to be known variously as “Old Pete” and “Old War Horse”, resigned his commission to join the Confederate forces. Longstreet’s performance in various engagements during the early stages of the war gained him Lee’s confidence, as a result of which he was given command of a “wing” of the Army of Northern Virginia. NA

Although McDowell managed to lift this cloud from his record, he would not receive another field command. Instead he served on commissions and boards in Washington until 1 July 1864 when he was sent west to take over the Department of the Pacific, which was then headquartered in San Francisco.

On 1 September 1866, McDowell mustered out of volunteer service, but secured a billet as a brigadier general in the Regular Army, and six years later advanced to major general, the grade at which he retired in 1882. He ultimately became park commissioner for the City of San Francisco.

In 1852 Franz Sigel left his native Baden bound for the United States. He was an outspoken liberal, and had supported the unsuccessful Revolution of 1848 against Prussia. This former army officer was subsequently forced to flee his native land, and not long after landing in his new country, he made his way to St. Louis, Missouri. He worked there for nearly a decade as a schoolteacher. Then, in 1861, having become something of a pillar of the influential German population in the area, he attracted Lincoln’s attention. The president desired to win support among transplanted Europeans with an anti-slavery, Unionist bent. With this objective in mind, during the summer of 1861, Sigel was commissioned as a brigadier general of volunteers.

Thereafter he became active in Missouri, fighting at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek. On 8 March 1862, he commanded two divisions at the Battle of Pea Ridge, helping defeat Southern troops under Major General Earl Van Dorn.

Promotion to major general followed on 22 March 1862. Soon afterwards he was brought to the eastern theater to face Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley. When Pope was selected to command the Army of Virginia, Sigel was appointed commander of I Corps. Following the Second Manassas campaign he briefly commanded XI Corps in the Army of the Potomac, but his military career was lackluster at best after that. Sigel’s defeat at the Battle of New Market (15 May 1864), led to his removal from field command. Almost a year later he resigned his commission, returning to civilian pursuits until his death in 1902.

As the son of a Revolutionary War hero it came as no surprise when young Robert E. Lee obtained an appointment to West Point. He entered the academy in 1825, and after four years as a cadet had managed to avoid receiving even one demerit. In addition, he graduated second in his class of 1829, which earned him a commission as second lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers.

His first assignment to work on fortifications at Hampton Roads was followed by a detail to serve as an assistant to the chief of engineers, a duty that began in 1834. This posting to Washington allowed him to live in a fine home that his new bride’s family had given the couple. The stately home still stands overlooking Arlington National Cemetery.

Lee then went on to other duties, not the least of which was on Winfield Scott’s staff during the Mexican War, where he served at both Cerro Gordo and Churubusco. He conducted reconnaissance during this period that greatly assisted the movement of Scott’s forces. His services brought three brevets and Scott’s highest accolade. He ultimately pronounced Lee “the very best soldier that I ever saw in the field.”

Except for Robert E. Lee, no other Confederate commander gained such renown or was more exalted than Thomas J. Jackson. A graduate of the class of 1846 at West Point, Jackson had served in the artillery in the Mexican War, where he earned two brevets. After the war he resigned his commission, and took up a post at the Virginia Military Institute, where the humorless professor no doubt would have remained in obscurity had it not been for the Civil War. Certainly an eccentric he was undoubtedly one of the South’s boldest and most aggressive commanders. He played a key role in the Confederate prosecution of the war until his tragic death following the battle of Chancellorsville. NA

Lee went on to become the commanding officer of the 2nd US Cavalry, and later the superintendent of West Point. Soon after the Civil War began, Lee’s first-class reputation prompted Lincoln to offer him command of the Federal Army. He declined then resigned his commission, offering his services to his native state of Virginia.

On 23 April 1861, his offer was accepted with the rank of major general in the Virginia state forces. By 14 May he was also commissioned as brigadier general in the Confederate Regular Army. A month later he jumped to full general.

Jefferson Davis quickly appointed him as his military advisor, but after Joseph Johnston was wounded at Seven Pines, Lee departed Richmond to replace him. Thereafter, he remained in the field for the duration of the war, gaining many laurels and a legendary status. President Jefferson Davis ultimately appointed him general in chief of the Confederate States Army on 31 January 1865. It was, however, far too late for even Lee’s prodigious talents to turn the tide.

Lee was a very different type of military leader from Pope, except in one respect. He, too, sought a classic confrontation in the mold of Austerlitz. According to eminent military historian Russell Weigley, at Second Manassas Lee “came as close as any general since Napoleon to duplicating the Napoleonic system of battlefield victory by fixing the enemy in a position with a detachment, bringing the rest of the army onto his flank and rear, and then routing him from the flank.” It was a perfect textbook execution, but as Weigley concluded: “Lee was too Napoleonic. Like Napoleon himself, with his passion for the strategy of annihilation and the climactic decisive battle as its expression, he destroyed in the end not the enemy armies, but his own.”

South Carolinian James Longstreet began his military career as a cadet at West Point, graduating in 1842, as one of John Pope’s classmates. He then received his commission as a second lieutenant in the infantry, and his first field duty was in Florida. After that he served in the Mexican War where he received a wound at Chapultepec. His actions in this conflict brought two brevets. Duty on the frontier followed, but eventually he transferred to the Paymaster Department and there he secured the rank of major.

On 1 June 1861, he resigned his US Army commission and sought a post as paymaster with the Confederate forces. Instead, on 17 June, he was made a brigadier general and placed in command of a brigade. By early October, he rose to the rank of major general, at which time he became a divisional commander. He subsequently participated in the Peninsula Campaign, Yorktown, Williamsburg, Seven Pines, and the Seven Days.

His performance in these various engagements gained Lee’s confidence. Because of this he was placed in charge of a “wing” of Lee’s forces, a term that was pressed into service at that time to evade a piece of early Confederate legislation that disallowed organizations larger than a division. Ultimately Lee was able to have this prohibition repealed, and at that point Longstreet officially took command of I Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia, which in addition to other elements contained over 50 per cent of that army’s infantry.

At the outbreak of the war some Union troops appeared in gray uniforms, as shown in this portrait of Henry H. Richardson, a subaltern with Company F of the 21st Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. This regiment fought at Henry Hill on 30 August 1862. USAMHI

Although he was not as aggressive in pressing the enemy at Second Manassas as Lee may have wished, Longstreet nevertheless generally served his superior well. In fact, Longstreet’s seizing of Thoroughfare Gap proved pivotal in the ultimate routing of Pope’s troops. This accomplishment and his actions at Sharpsburg soon thereafter, led to his promotion to the rank of lieutenant general.

His friends sometimes called him “Pete” but to others he became Lee’s “Old War Horse”. Despite this latter title, his inclination toward strategic offense and tactical defense differed from that of his superior. While Longstreet’s philosophy was correct in some instances, such as at Gettysburg, his incapacity for independent operations marred his reputation. Whatever Longstreet’s shortcomings, he remained at Lee’s side until the final surrender at Appomattox.

Except for Robert E. Lee, no other Confederate commander gained such renown or was more exalted than Thomas J. Jackson. A graduate of the class of 1846 at West Point, Jackson had served in the artillery in the Mexican War, where he earned two brevets. After the war he resigned his commission then took up a post at the Virginia Military Institute, where the humorless professor no doubt would have remained in obscurity had it not been for the Civil War. Cadets considered him peculiar to say the least, and they gave him such nicknames as “Tom Fool Jackson” and “Old Blue Light”, in the latter instance because of his penetrating blue eyes.

Some of Irvin McDowell’s men encamped at Culpeper, Virginia, a town that boasted a key depot on the Orange & Alexandria Railroad. The seated man appears in the typical combat uniform that came to be associated with the Union Army – the dark blue “bummer’s” cap, with dark blue, four-button sack coat and sky-blue kersey trousers. USAMHI

Matthew Brady captured another gray uniform worn by a Northern officer, in this case an ornate example donned by the one-time commander of the 5th New York, Abram Duryée. Early in the war Duryée put aside this outfit for a brigadier general’s uniform. At Second Manassas he commanded the 1st Brigade, 2nd Division of III Corps, under McDowell. During the battle he received two wounds, but nevertheless continued on active duty. USAMHI

When war came he accepted a colonelcy in the Virginia forces. He was soon ordered to the Union arsenal at Harpers Ferry. From there he marched with Joseph Johnston, as commander of 1st Brigade, Army of the Shenandoah. Newly promoted to brigadier general on 17 June 1861, Jackson was part of Johnston’s army that moved to unite with Brigadier General Pierre Beauregard’s troops at Manassas. Jackson’s conduct during the subsequent First Battle of Manassas gained both he and his brigade the name “Stonewall”.

By the fall he was a major general with responsibility for the strategically important Shenandoah Valley. He would again sting the enemy, but not always with the desired results. For instance, at Kernstown (23 March 1862) he suffered a defeat, for which the pious soldier partially blamed himself because he had fought on a Sunday. Nevertheless, he was able to divert Federal reinforcements to the valley and away from the attack on Richmond.

In May Jackson’s performance improved. He halted Major General John C. Frémont’s advance from West Virginia at McDowell, then took the offensive against a number of other Union commanders, none of whom could bring him to bay. His victories in the Valley Campaign behind him, Lee ordered Stonewall to assist in the defense of Richmond.

Once George McClellan had withdrawn after the Seven Days battles, Lee sent Jackson north, informing him in a letter, “I want Pope to be suppressed … ” Knowing Jackson’s propensity to keep his plans to himself, Lee’s missive also suggested, “advising with your division commanders as to your movements, much trouble will be saved you in arranging details, and they can act more intelligently.” Unfortunately, Jackson never took this sage counsel to heart.

At Cedar Mountain he committed his forces piecemeal, suffering unnecessary casualties in his eagerness to engage General Banks’s Corps. His flanking movement later in the Manassas campaign was executed with great daring and threw Pope’s Army of Virginia off balance. He then held firm in the face of determined attacks until Longstreet was able to roll up the Union left flank.

After Second Manassas, Lee once again detached Jackson and charged him with the seizure of Harpers Ferry. He subsequently rejoined Lee at Sharpsburg. Then came another promotion and command of II Corps.

Fredericksburg followed; then Chancellorsville, where his men outflanked the Union right and devastated the XI Corps of the Army of the Potomac. Later that night, as Jackson was returning from a reconnaissance, some of his own men opened fire, striking him in the arm which was amputated. Complications set in, and on 10 May 1863 he died of pneumonia, depriving the South of one of her greatest commanders.