When Jackson began his withdrawal from Manassas on the evening of 27 August, which included the wholesale destruction of whatever his men could not carry off, he marched north toward Centreville and other sites along the Warrenton Pike. This would make it more difficult for Pope to cut him off from the approaching Longstreet. By the next morning, Jackson reported that he made immediate disposition of his command based upon the belief that the Union main body “was leaving the road and inclining toward Manassas Junction.” Thus, in his own words, he advanced his command “through the woods, leaving Groveton on the left, until it reached a commanding position near Brawner’s house [the residence of a local farmer named John Brawner].”

Jackson’s guess about Pope’s plans proved correct. He had indeed directed the Army of Virginia to converge upon Manassas Junction, where he believed the Confederates were in position. A brief fracas with some of Sigel’s troops on the morning of 28 August confirmed Jackson’s suspicions. During the fight, Captain George Gaither’s troop of the 1st Virginia Cavalry managed to capture a courier, who carried the order of march for the Union forces dictated by Pope. Jackson knew what his enemy had in mind – the same could not be said of Pope.

In fact, Sigel had captured some Confederate prisoners as well, but the information they gave misleadingly indicated Jackson was still at Manassas. In reality the men of William Taliaferro’s Division were concealed in the woods north of Groveton, with another division under Richard S. Ewell heading toward Stone Bridge, and A.P. Hill’s Light Division moving westward from Centreville towards the Groveton area.

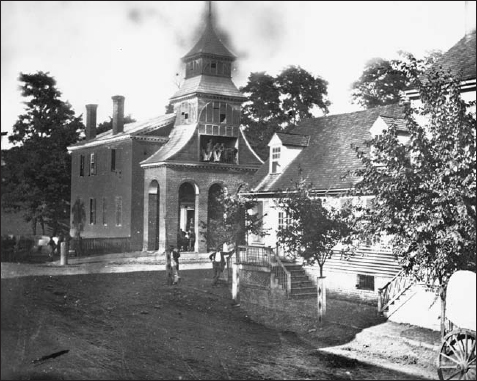

In the aftermath of Cedar Mountain, local citizens, such as the Robinson family, who owned this home, could return to their precarious lives. USAMHI

Late in the afternoon with Jackson’s men out of sight in the woods, a Federal column marched onto the scene. Brigadier General John F. Reynolds’s Division was in the vanguard, and engaged in a brief clash with a Southern screening detachment. The action was brief and Reynolds continued on toward Manassas Junction, not realizing the Confederates were concealed nearby.

Following behind came Rufus King’s Division at around 5.00pm. A little earlier, McDowell had been with King, but had departed in search of Pope to confer with his superior. King was thus the senior officer although he was unwell, having recently suffered an epileptic seizure. Unfortunately, he would be debilitated by another attack later that evening.

Given the number of troops who fell on 9 August the Confederate name for the battle, Slaughter Mountain, was appropriate. But it was the home of Reverend Slaughter, who lived on the mountain that was the source of the name.

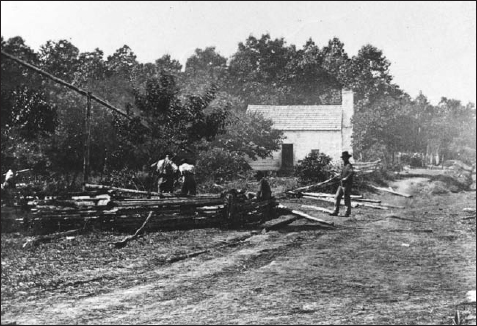

The Confederates lost 1,418 troops killed or wounded at Cedar Mountain, including Brigadier General Charles S. Winder, who led Jackson’s 1st Division. Winder breathed his last in this rustic residence. USAMHI

The Union buried 314 of their dead on the field, almost in the shadow of Cedar Mountain. In all 2,403 Union men were wounded, killed, or missing after the battle. LC

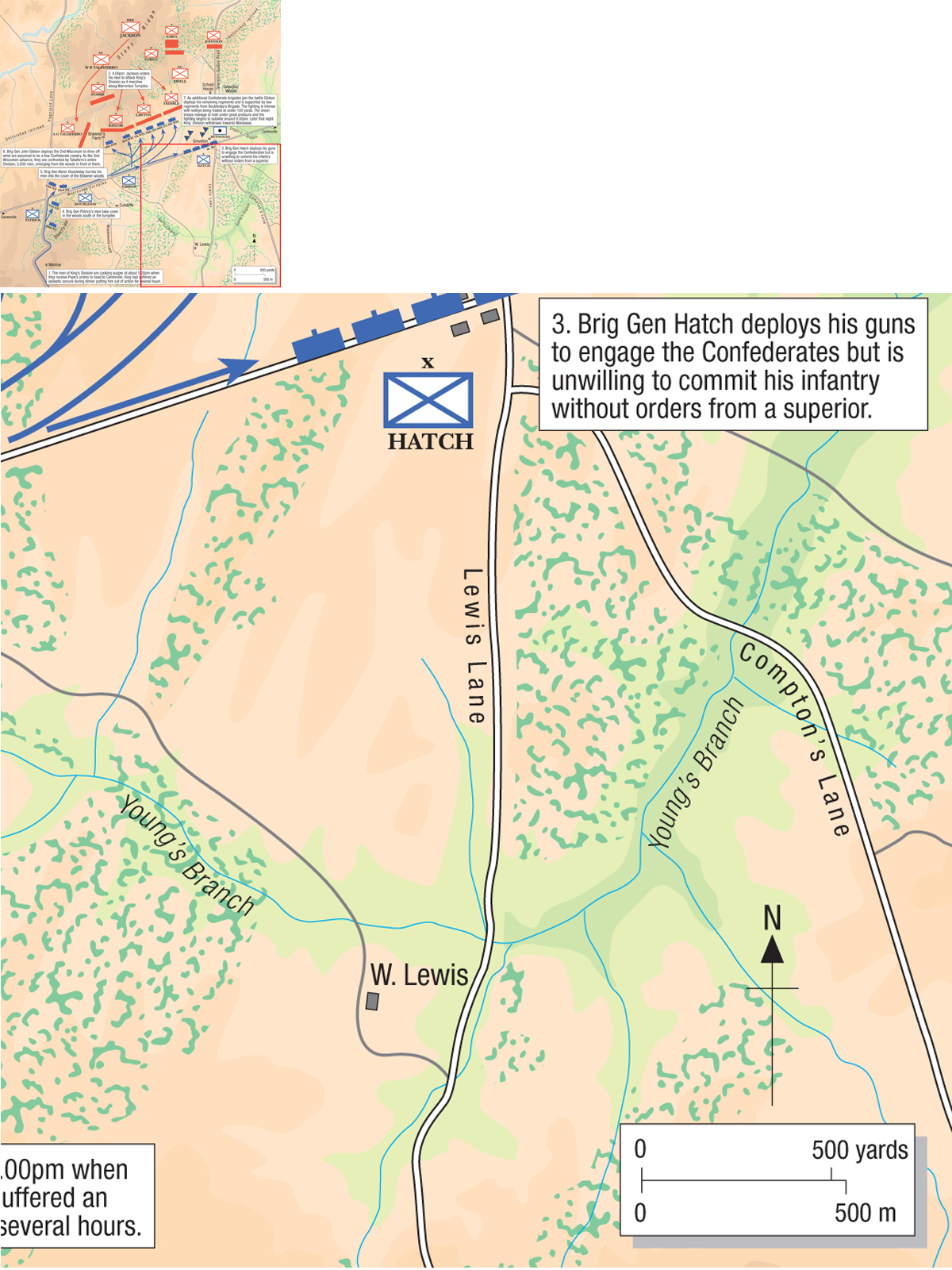

Unaware of their commander’s condition, the division proceeded along the turnpike, with the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry riding point for the lead brigade under John P. Hatch. The cavalrymen noticed nothing unusual, nor did the 14th Brooklyn, a zouave unit that Hatch sent out as flankers to guard against surprise attack. They, too, failed to detect the enemy waiting in numbers to spring an ambush.

Stonewall had placed three batteries in front of William E. Starke’s brigade above the village of Groveton along Stony Ridge. Jackson told his division commanders Ewell and Taliaferro “Bring up your men, gentlemen!” In short order, the Virginia gunners of Captain Asher Garber’s Staunton Artillery began to fire over the heads of Confederate skirmishers. The gates of Hell had opened; Manassas would once again be the arena for a bloody struggle between North and South.

Garber’s artillerists had the Federals targeted after only three rounds. They were soon joined by the other two batteries, causing the Union troops to sprint for cover. Hatch ordered up one of his own batteries, Battery L, 1st New York Light Artillery, captained by John Reynolds. The six 3-in. ordnance rifles took position north-west of the scattering of half a dozen simple buildings that made up Groveton. Men of the 24th New York Infantry rapidly dismantled a fence obstructing the field of fire, allowing Reynolds to bring his pieces to bear.

The Yankees were outgunned though, as George Breck, a lieutenant in the outfit indicated. Breck wrote: “The shot and shell fell and burst in our midst every minute, exploding in the middle of the road between men and horses and caissons, throwing dirt and gravel all over us, and making it impossible for the cannoniers to man their pieces.”

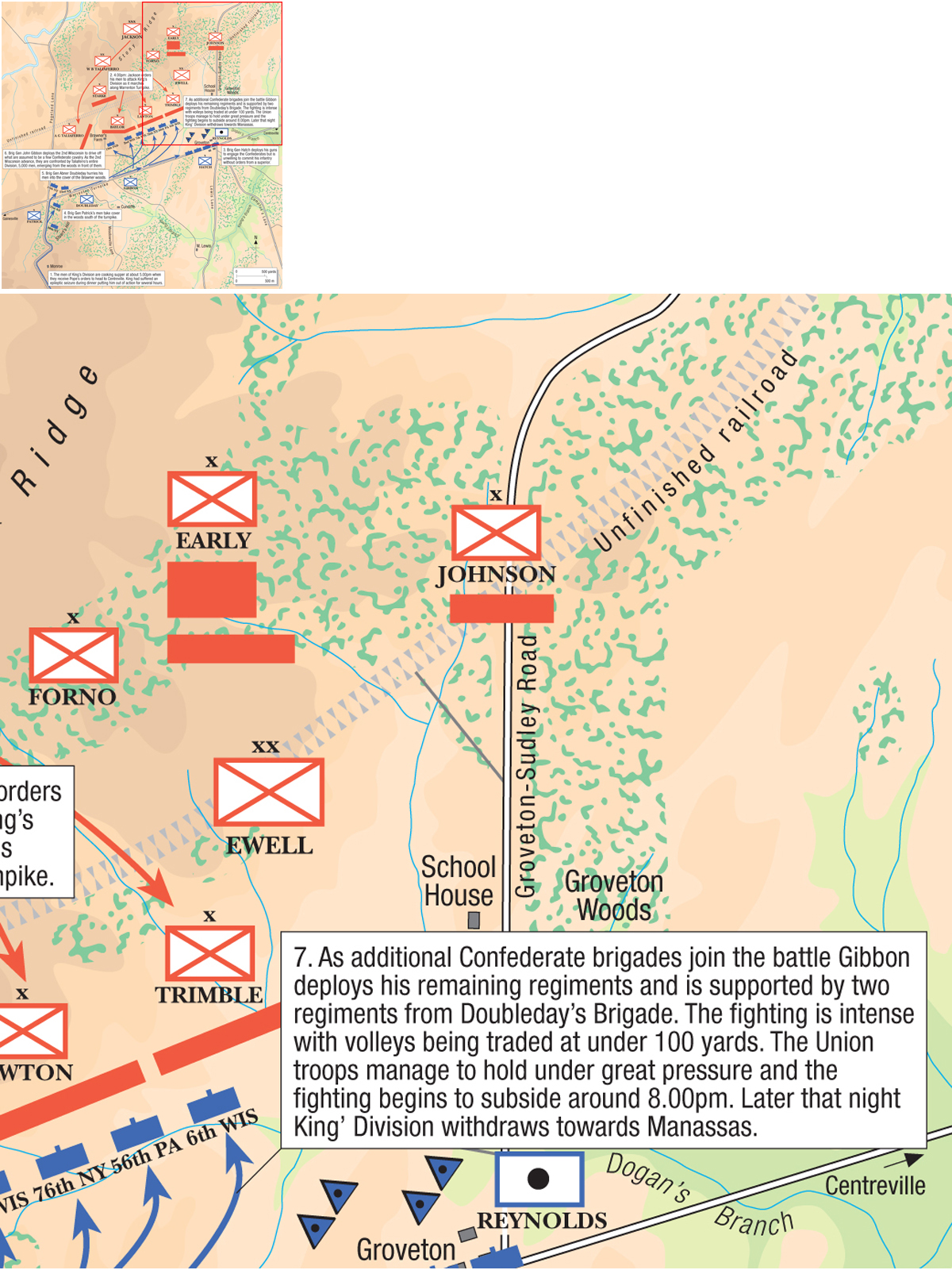

On 28 August at Brawner’s Farm the untried 2nd, 6th, and 7th Wisconsin infantry regiments, and the 19th Indiana of BrigGen John Gibbon’s “Black Hat Brigade” underwent their baptism of fire. Around 6.00pm they engaged what Gibbon believed to be a cavalry rearguard supported by artillery. Leading his men forward Gibbon soon realized that the Rebels were present in strength. His 2,100 Midwesterners faced Taliaferro’s Division 6,200 strong. Before reinforcements could arrive, the Federal and Confederate forces had closed to within 75 yards of each other. The action continued until nightfall and Gibbon’s units took 33 per cent casualties. The resolve displayed by Gibbon’s men in this and later actions was soon to win them a new name as “The Iron Brigade” of the Union Army. (Mike Adams)

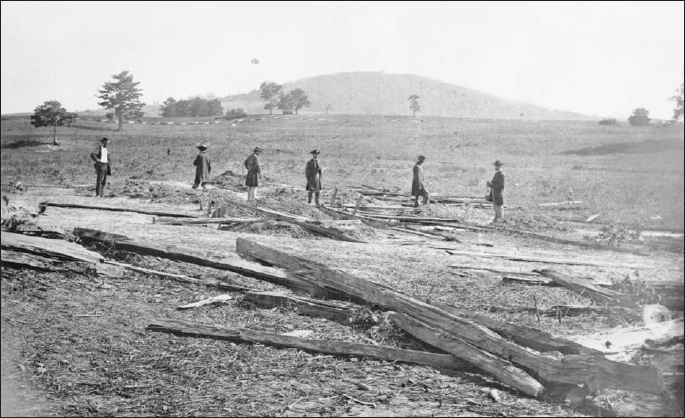

The 10th Maine served in Brigadier General Samuel Crawford’s Brigade, 1st Division, II Corps of the Army of Virginia. The regiment was at Cedar Mountain. Officers from this unit have returned a few days after the clash, perhaps to reflect on the fighting of 9 August. USAMHI

During the pounding, Hatch’s infantrymen remained frozen in place. Marsena Patrick’s unblooded command, which brought up the rear of the column, likewise halted and sought protection in the woods to the south of the roadway. Another of King’s brigades led by Abner Doubleday left the pike, too, and headed into the woods that stood on Brawner’s farm.

Only Southern-born John Gibbon, who had three brothers in the Confederate forces took the fight to the enemy. After Gibbon’s 6th Wisconsin, which marched at the head of his column, came under attack, he formed his men into a battleline. He also deployed the artillery of Captain Joseph Campbell’s Battery B, 4th US Artillery. Campbell’s regulars unlimbered their 12-pdr Napoleons on high ground to the east of Brawner’s farmstead.

Men and horses fell at Cedar Mountain. The carnage of war was evident for sometime after the battle. USAMHI

Confederate soldiers taken as prisoners of war during Cedar Mountain hang out their laundry to dry from their impromptu place of incarceration in Culpeper, Virginia. LC

In the meantime, without a corps or division commander to take charge, Gibbon rushed off to consult with Doubleday. The latter officer postulated that Jackson was in Centreville, and therefore the column only faced cavalry, who could be driven off with relative ease. With that Gibbon rode back to his men and launched his only veteran unit, the 2nd Wisconsin, against the Confederate artillery.

As the Federals advanced on the Southern guns, the 800 men of the veteran Stonewall Brigade emerged from the woods. The fighting was ferocious, with the two sides exchanging volleys at a scant 80 yds! Despite the devastating power of rifled musketry at this range, neither Union nor Confederate forces gave way. Confederate Brigadier General Taliaferro stated, “Out in the sunlight, in the dying daylight, and under the stars they stood, and although they could not advance, they would not retire.”

Talaiferro further described the scene as “one of the most terrific engagements that can be conceived … ” Confederate troops “held the farmhouse,” he concluded, while “the enemy held the orchard. To the left our men stood in the open field without shelter of any kind.” It appeared to Taliaferro like a painting depicting a moment of battle frozen in time. This surreal situation continued for some 20 minutes before the 19th Indiana came up to support the stalwart Wisconsin soldiers on their left. The commanding officer of the Hoosier troops, Colonel Solomon Meredith, captured the moment: “The enemy was secreted under cover of a fence and did not make their appearance until we had approached to within 75 yards. Immediately upon our halting the enemy fired. Three different times they came up at a charge, but the 19th stood firm.” And each time the Confederates fell back to their fence line.

Some residences in the vicinity of Cedar Mountain were pressed into service as medical facilities for the several thousand casualties that were sustained during this brief, but sharp engagement. USAMHI

After Cedar Mountain, Clara Barton was one of the individuals who set to work to care for the wounded and dying. Decades later she became a prime mover in the founding of the American Red Cross. NA

Meanwhile, on the right, Starke’s Louisianians pressed the Federal troops. Jackson also sent nearly half of the Georgians from Lawton’s Brigade to lengthen the Confederate line, but they met stiff opposition from the 7th Wisconsin, which Gibbon had added to his line. These blue-coated foot soldiers stood their ground, keeping the Southerners from moving forward, although the two forces remained but 100 yds apart.

The 6th Wisconsin, the last remaining regiment under Gibbon, also was sent to the front of Campbell’s Battery. This regiment’s commanding officer, Colonel Lysander Cutler, after learning that the 2nd Wisconsin was being slaughtered, and receiving the order to “join on the right of the 7th [Wisconsin] and engage the enemy,” took his place in front of his command. Once in position, he called out, “Forward, guide center, march.” In response, according to Major Rufus Dawes of the 6th, “ … every man scrambled up the bank and over the fence, in the face of shot and shell … ” Thus, by 6.45pm Gibbon’s whole brigade was engaged in furious action.

Their adversaries clearly were not just a few Confederate cavalry troopers, but a strong force of infantry with substantial artillery support. There were six Southern brigades with 6,000 fighting men pitted against Gibbon’s 2,100. Gibbon certainly needed urgent support, and made this known in a dispatch to divisional headquarters. When no response was forthcoming, Gibbon turned to the other brigade commanders. Again there was silence, except from Doubleday. To his credit, Doubleday did not stand by and watch the butchery. He sent two of his regiments, the 76th New York and the 56th Pennsylvania into the whirlwind. Still the battle raged. Colonel Dawes again depicted what he saw: “Through the intense smoke, through which we were advancing, I could see a blood red sun sinking behind the hills … The two crowds, they could not be called lines, were within, it seemed to me, fifty yards of each other, and they were pouring musketry into each other as rapidly as man can shoot.”

Confederate forces had wintered around Manassas, but had abandoned Fort Beauregard by the time this picture was taken in March 1862. USAMHI

Captain James S. Blain of the 26th Georgia Infantry knew what it was like to be on the receiving end of these volleys. He indicated the Georgians had been “ordered in just after dark.” They “marched steadily across an open field for about 400 yards, over which the balls were flying by the thousands.” Brigadier General Lawton was determined to press on. He ordered a charge. Captain Blain admitted: “The Yankees did fearful execution; men fell from the ranks by the dozens.”

Undaunted, by 7.15pm Jackson decided to increase the intensity of the offensive. He had reserves from Ewell’s command on hand, and Hill was approaching. He thought it was time for a head-on onslaught. This action fell to the 21st Georgia and the 21st North Carolina, known as the “Twin Twenty-ones”, of Brigadier General Isaac Trimble’s Brigade. They were ordered to assault the right of the Federal line, while Alexander Lawton’s Brigade was to press the attack to their right, closer to the Union center.

Captain James F. Beal, who commanded a company of the 21st North Carolina, provided a Southern perspective on this stage of the fighting. He revealed that the Confederate infantrymen halted at a fence, which they quickly tore “down and piled the rails in front. It offered good protection.” He went on to assert: “The Federals were in a gully, or branch about 100 yards distant. We opened fire on them, but it soon became so dark that we could not see their position, but could only fire at the flashes from their guns, as I suppose they would fire at ours.”

Sergeant Uberton Burnham of the 76th New York Infantry provided a view of the engagement from the Northern ranks: “Waving their colors defiantly, the rebels advanced from the woods to charge upon Gibbon’s brigade to our left. Gibbon’s men did not run. Those western men are not easily scared. They stood still and fired as fast as they could. We gave the Rebs a crossfire, thinning their ranks and prostrating their color bearer. The Rebels finding they were getting the worse of it turned their backs and pointed for the woods.”

Curious Virginia lads look on as Yankee cavalrymen water their mounts. Soldiers from both sides criss-crossed the state as the summer of 1862 campaign was waged. LC

When Jackson did not achieve his aim on the right, the Union left became his next target. The gallant Confederate artilleryman John Pelham rushed his guns to within 100 yds of the 19th Indiana. Following Pelham’s bombardment, the last three regiments in W.B. Taliaferro’s Division, commanded by his uncle Colonel A.G. Taliaferro, advanced. Gibbon was forced to withdraw the 19th, but the Indianians were able to slow Taliaferro’s Third Brigade. The attack ceased, as darkness and exhaustion brought an end to the fighting.

A private from the 2nd Wisconsin, Nathaniel Rollins, summed up the trying events of that 28 August. “Rebel infantry,” he said, had “poured from the woods by the thousand.” He continued: “For an hour and fifteen minutes the most terrific fire imaginable was kept up; the hill top, the valley, and the wooded side of the hill beyond was a continuous sheet of flame. Darkness came on, the stars came out, and still the bullets filled the air.” By 9.00pm, however, Gibbon and Doubleday agreed that it was time to make an orderly withdrawal.

Gibbon’s men in particular had performed admirably. The steely determination displayed in this and subsequent actions would earn his men the reputation as the “Iron Brigade” of the Northern armies. Despite the fact that they had been set upon without warning, the Federals sustained fewer casualties than the Confederates, with an estimated 1,000 dead and wounded.

The former Confederate facilities at Fort Beauregard provided the Union men with all the comforts of home, including a privy. Routine camp life would give way to campaigning once Pope took charge. USAMHI

Nevertheless, the Confederates gave a good account of themselves that evening, and during the course of the fighting some 1,250 had fallen, including nearly 40 per cent of Stonewall’s seasoned brigade. This was a dreadful blow in all respects, as was the loss of Ewell, who having been wounded during the encounter, subsequently lost his leg to amputation. This put him out of action for some time, depriving Lee of one of his more pugnacious and dependable officers. William Taliaferro likewise was wounded. Because of this, William E. Starke was temporarily assigned command of the division, while Ewell’s Division was placed under a Harvard-educated attorney named Alexander R. Lawton.

Both wounded divisional commanders had demonstrated shortcomings during the action. Ewell had been slow in bringing his forces to the field and William Taliaferro had held back one of his brigades, and committed the others piecemeal.

Although Pope now knew the whereabouts of Jackson’s wing, he seemed totally unconcerned as to the location and intentions of Longstreet’s men. This oversight was to prove costly in the days to come.

In fact, Longstreet and Lee had halted at White Plains on the evening of 27 August. His column did not press forward with any great urgency despite Jackson’s apparent vulnerability. Even on 28 August, Longstreet’s forces did not break camp until 11.00am. to march toward Thoroughfare Gap. This was a rugged cut through the Bull Run Mountains that narrowed to as little as 100 yds in some places. Its north face was nearly perpendicular, with the south face less steep, but covered with tangles of ivy and boulders that provided excellent cover for anyone determined to hold the pass. Down the center ran a muddy stream from which rose walls of rock that measured several hundred feet in height.

Jackson had passed through the Gap on his march to Manassas, and it was an obvious route for the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia. Indeed, the Federals had received intelligence that Longstreet was marching on the Gap. As such, it seemed reasonable to expect this pass would be guarded by a strong Union force. On his own initiative, Major General McDowell ordered the 5,000 men of James B. Ricketts’s 2nd Division to secure this vital pass, which was held only by the lst New Jersey Cavalry.

McDowell’s instincts were excellent, but Ricketts’s command was no match for Longstreet’s superior numbers. Even as he approached Thoroughfare Gap the New Jersey troopers were falling back, having been overwhelmed by the Southern advance.

Ricketts’s response was to commit the 11th Pennsylvania Infantry, just as the Confederate 9th Georgia were setting up camp just east of the Gap. The Federal strike caught the Georgians by surprise, and the Pennsylvanians briefly gained the upper hand – that is until Brigadier General D.R. Jones sent forward a brigade from his division with another in support. Even then the Northerners did not yield and the arrival of the 13th Massachusetts helped bolster the line. Ricketts’ men soon took up defensive positions, creating an impasse.

After dawdling for almost two days, Lee now became a dynamo. Colonel Evander Law’s Brigade was sent scrambling over the rugged mountains on Ricketts’ right, and C.M. Wilcox’s Division was sent further north to Hopewell Gap in a bid to turn Ricketts’s position. In addition, two regiments of Benning’s Brigade had won a race with a detachment of 13th Massachusetts to seize the summit of Pond Mountain on the southern side of Thoroughfare Gap. Law’s and Benning’s men succeeded in flanking Ricketts’s making his position untenable. He summarized the situation as follows: “The men moved forward gallantly but owing to the nature of the ground, the strongest positions being already held by the enemy, we were subjected to severe loss, without any prospect of gaining the gap.” Even under these circumstances Ricketts’s Division fought until darkness fell and then retired. At that point, nothing stood in Longstreet’s path to Jackson.

Longstreet’s move arguably constituted a major turning point for the Confederates. Not only did his breakthrough at Thoroughfare Gap allow him to combine with Jackson, but the fact that Pope seemed unaware of his presence had grave implications for the Army of Virginia.

Pope remained ignorant of Longstreet’s approach as he took a late supper around 10.00pm on 28 August. While dining, news reached him of King’s action at Groveton. He was delighted to learn that Jackson was still in the field, and was confident he could now bring the elusive Stonewall to bay. Pope dispatched orders for his commanders to concentrate their men at Groveton while King was to hold his ground to prevent Jackson escaping.

Although Pope intended King to maintain contact with Jackson, he learned that King had withdrawn to Manassas Junction at around 1.00am. A perturbed Pope issued new orders to his commanders around 5.00am on 29 August. These instructed McDowell to head toward Gainesville, taking King’s men with him, while Sigel was to attack the enemy vigorously, pinning him in position. However, Pope’s plan to surround Jackson was to disintegrate before him.