Three

WAR IN THE STREETS 1863

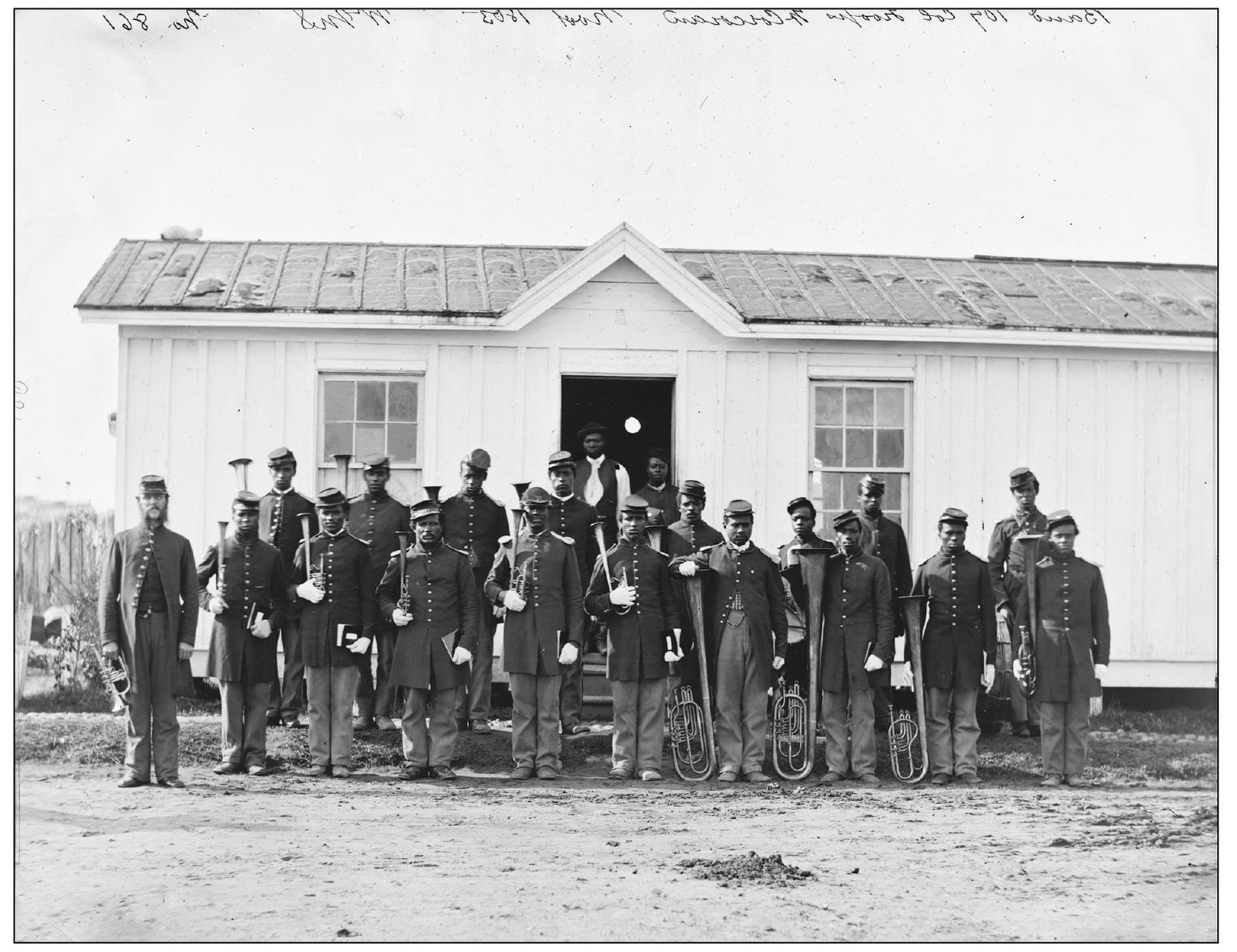

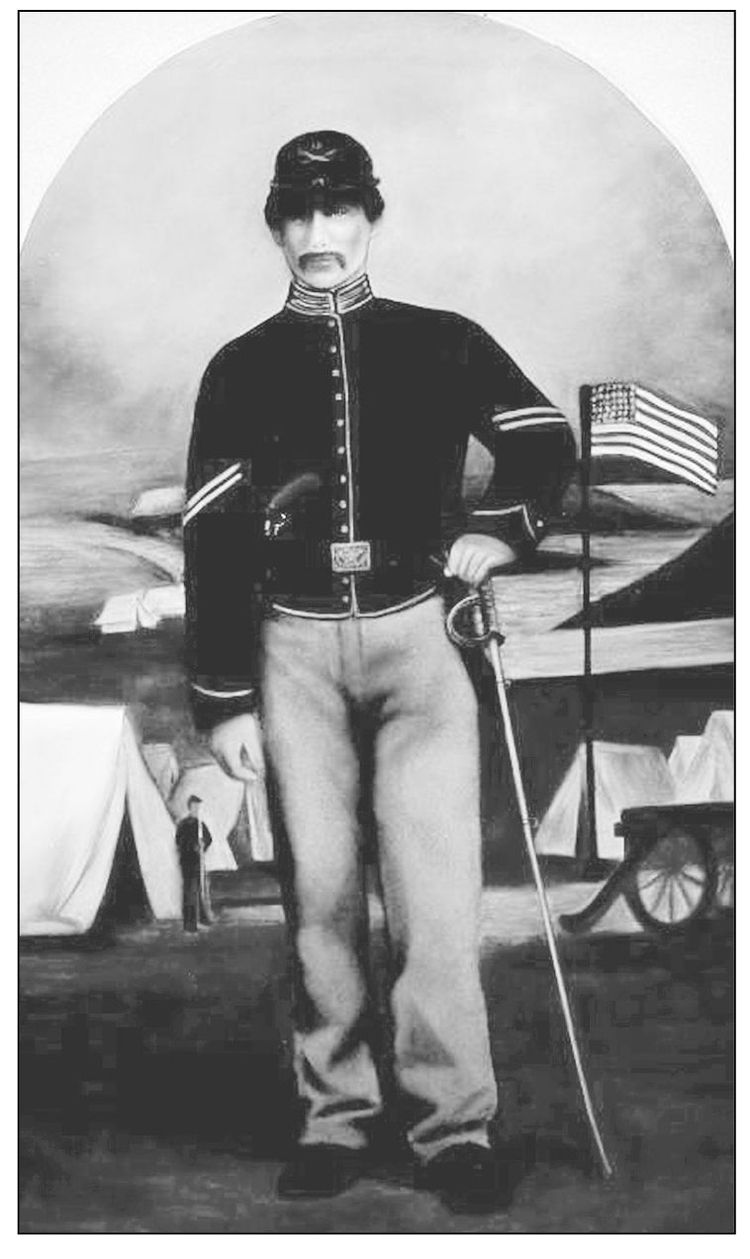

Prior to the Civil War, a group of local slaves formed a brass band and performed in what is now Jacob Wheaton Park. It was known as the Robert Moxley Band, named after the bandmaster. In 1863, the army began recruiting African Americans into segregated units. A recruiting officer saw the band perform and was so impressed that he arranged for the entire band to be enlisted as a unit. Designated the Number One Brigade Band, United States Colored Troops, it performed at recruiting drives promoting African American enlistment. It also served in the Petersburg Campaign before being transferred to Texas where the band mustered out in 1866. No photographs of the unit survive, but it would have appeared very much like the regimental band of the 107th United States Colored Infantry, pictured here. (Library of Congress.)

Young Leighton Parks lived with his mother on South Prospect Street. Robert E. Lee knew his father in the army. In June 1863, Lee invited the family to visit his headquarters near today’s Hickory Elementary School. Armed with a pail of raspberries, Leighton was the only Parks who visited. He offered a diversion for the homesick generals. Lee walked him on his horse, Traveller. General Longstreet, still recovering from the loss of his three youngest children the year before in a scarlet fever epidemic, enjoyed time bouncing Leighton on his knee. (WMR-WCFL.)

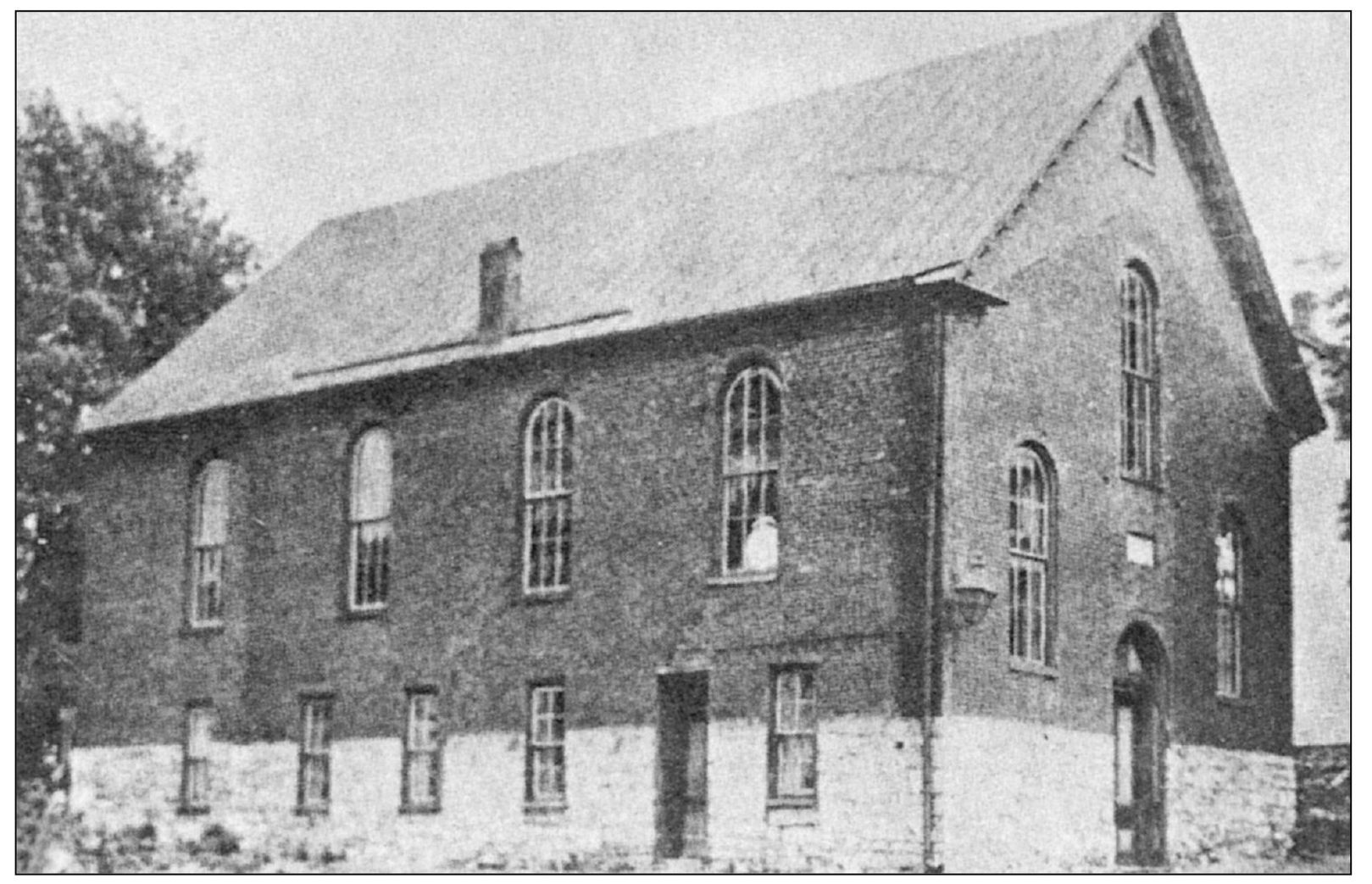

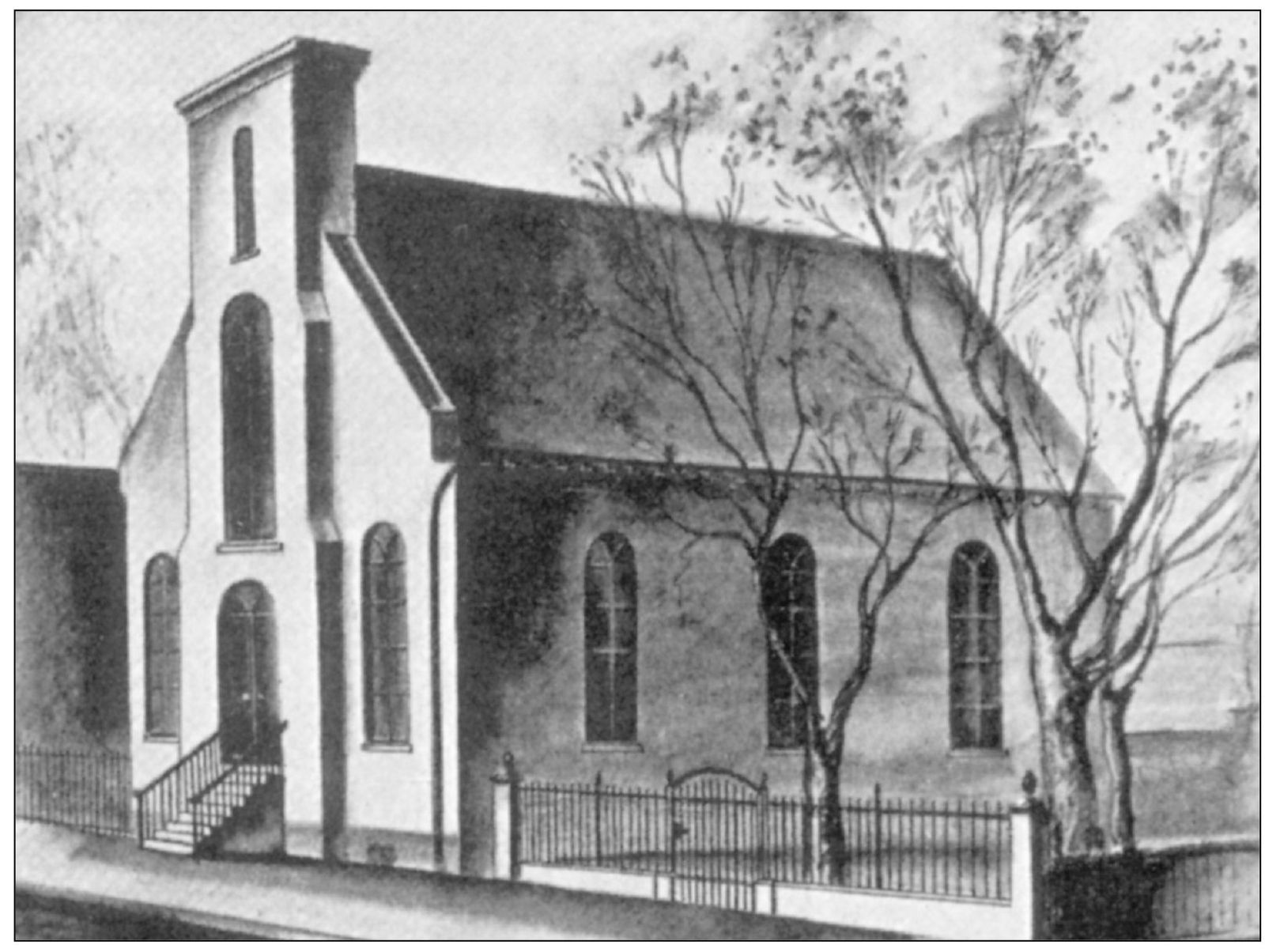

Ebenezer African Methodist Episcopal Church stood on Bethel Street from 1840 until it was rebuilt in 1910. In January 1863, several African Americans in town contracted smallpox. Fearing an epidemic, the town leased the basement for three months as a hospital “with arrangements for furnishing food and making them as comfortable as possible.” Dr. W. H. Lee cared for the sick, and local African Americans Thomas Henry and Jacob Wheaton were hired as steward and nurse. It is believed the church may have been used as a military hospital at times during the war. (Marguerite Doleman Collection.)

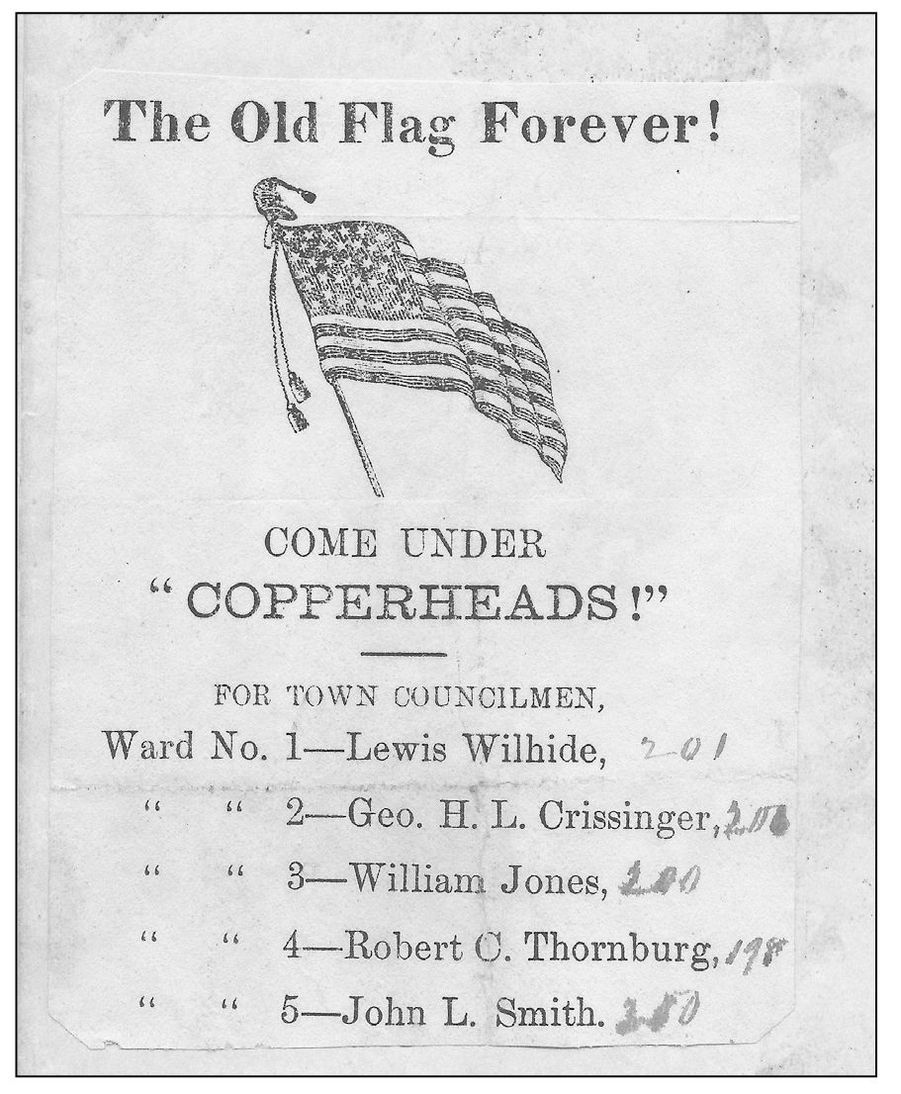

The annual election for city council was held around April 1, 1863. During the war, many communities settled on a “Union Ticket” and avoided contested elections that might serve to further divide the populace. This ballot from the 1863 election was recently discovered in the city council’s mid-19th century minutes book. Citizens would vote by handing a copy of the ballot to the election judge. The judge would then deposit the ballots into a box to be counted when the polls closed. (City of Hagerstown.)

After passing through Hagerstown in late June, the Army of Northern Virginia met disaster at Gettysburg on July 3. Torrential rains pounded the exhausted armies on July 4 and 5 as the rebels struggled to put an army and its thousands of supply wagons and ambulances full of thousands of wounded into motion. The rains quickly drove the Potomac River to flood stage, meaning the Union army could potentially trap the crippled Confederate forces before they could reach the relative safety of Virginia. (Author’s collection.)

Regardless of the miserable weather, the Union army moved to harass the retreating Confederates. General Meade’s infantry mostly marched toward Frederick to keep between the rebels and Washington, then turned west toward Williamsport hoping to cut off the Confederate withdrawal. Union cavalry attacked the Confederate trains at Monterrey and west of Cashtown, Pennsylvania. The warring armies crawled slowly through the mud toward Hagerstown. At 3:00 a.m. on July 5, troopers of the 1st Vermont Cavalry attacked a Confederate train at Leitersburg and captured 100 men and their wagons. So fatigued were the men of both sides that one reported “never had the men and horses been so jaded and stove up. One of our men who dropped at the foot of a tree in a sort of a hollow, went to sleep, and continued sleeping until the water rose to his waist ... battery horses would drop in their traces ... the men and officers on horseback would go to sleep without knowing it.” Other battles occurred in the area between July 5 and July 11, including such places as Cearfoss, Clear Spring, Smithsburg, and Boonsboro. This c. 1900 photograph of Leitersburg gives the reader an accurate view of what the weary cavalrymen and teamsters would have seen in town 37 years earlier. Pictured are Abraham Lincoln Smith; his wife, Catherine; and their daughters Maude and Sarah in front of the family’s tavern on the town square. (Dorothy Smith.)

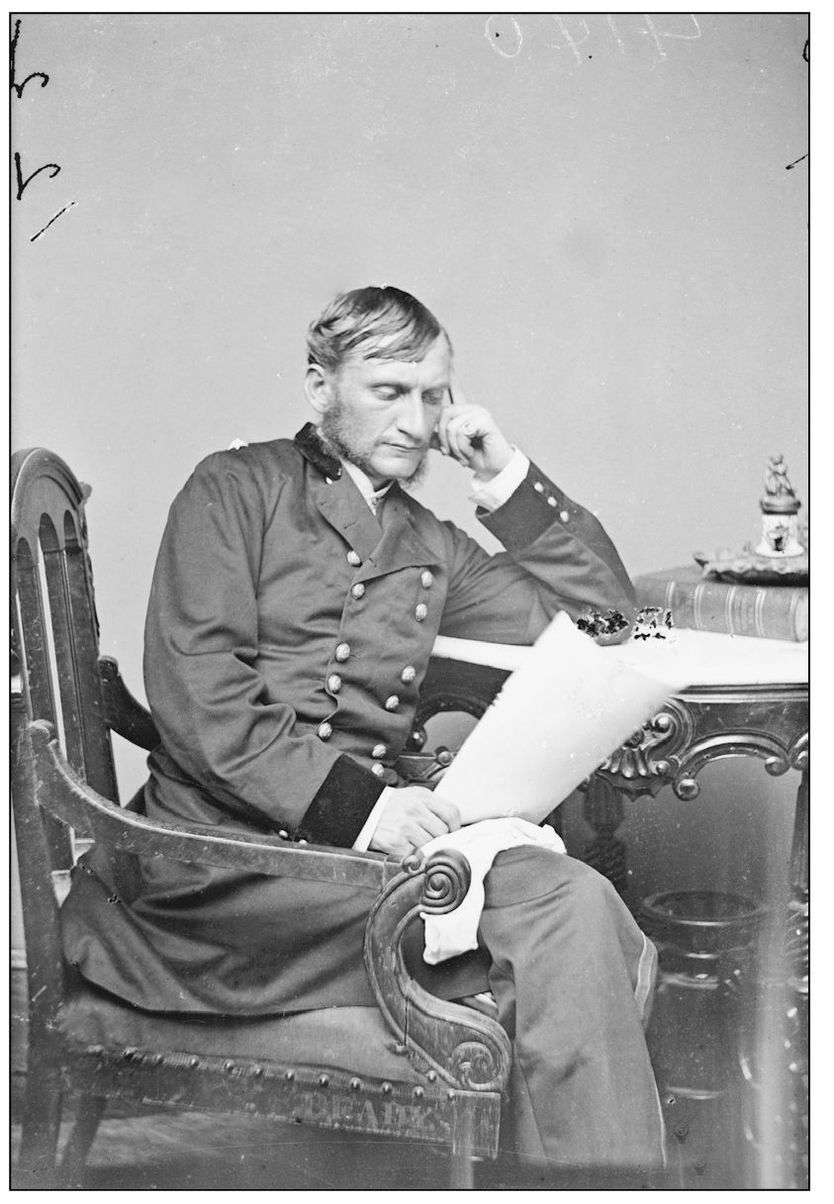

On July 6, 1863, combat reached the doorsteps of every Hagerstonian. Learning of a Confederate wagon train vulnerable to capture, Gen. Hugh Judson Kilpatrick (right) moved north from Boonsboro and ordered a charge into Hagerstown in an attempt to snare vital supplies. The battle opened around St. John’s Lutheran Church, where barricades were manned by the depleted ranks of the 9th and 10th Virginia Cavalry Regiments. They were overrun by squadrons from the 18th Pennsylvania, 1st Vermont, and 1st West Virginia Cavalry Regiments. The Yanks charged north from the area of today’s Rose Hill Cemetery. (Library of Congress.)

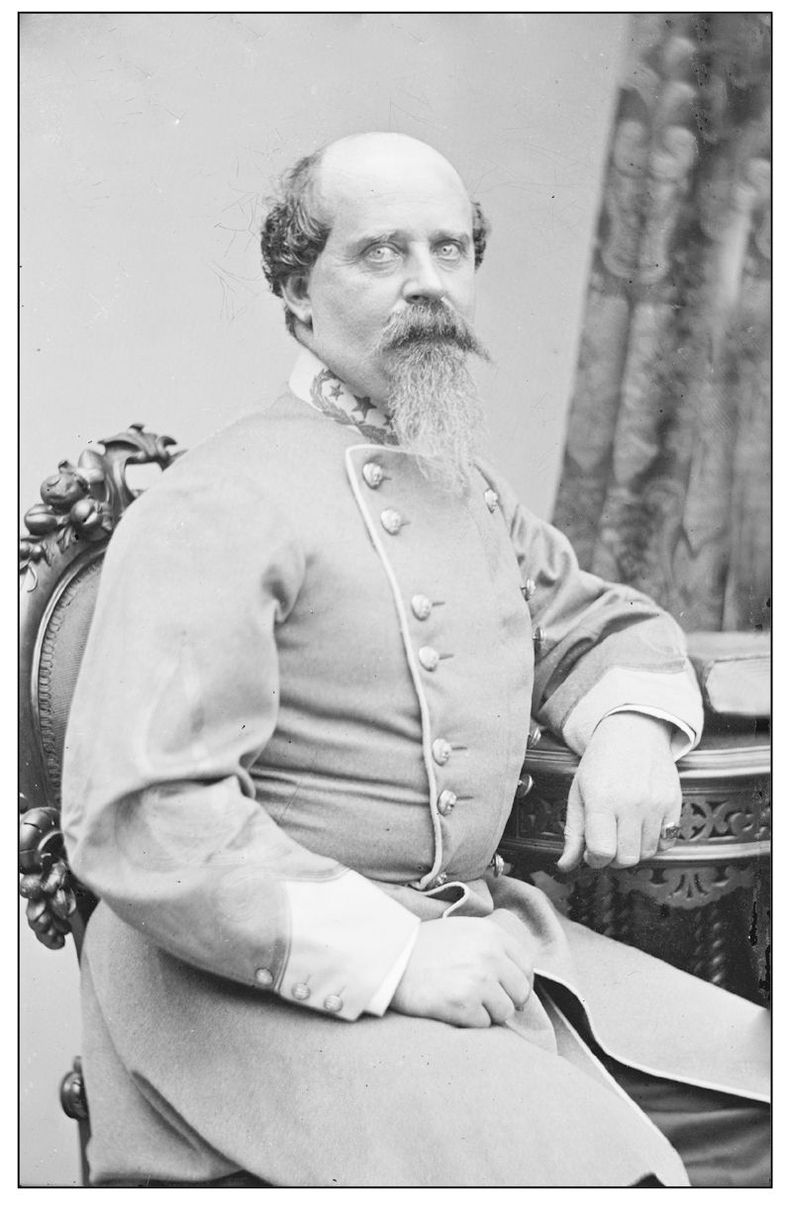

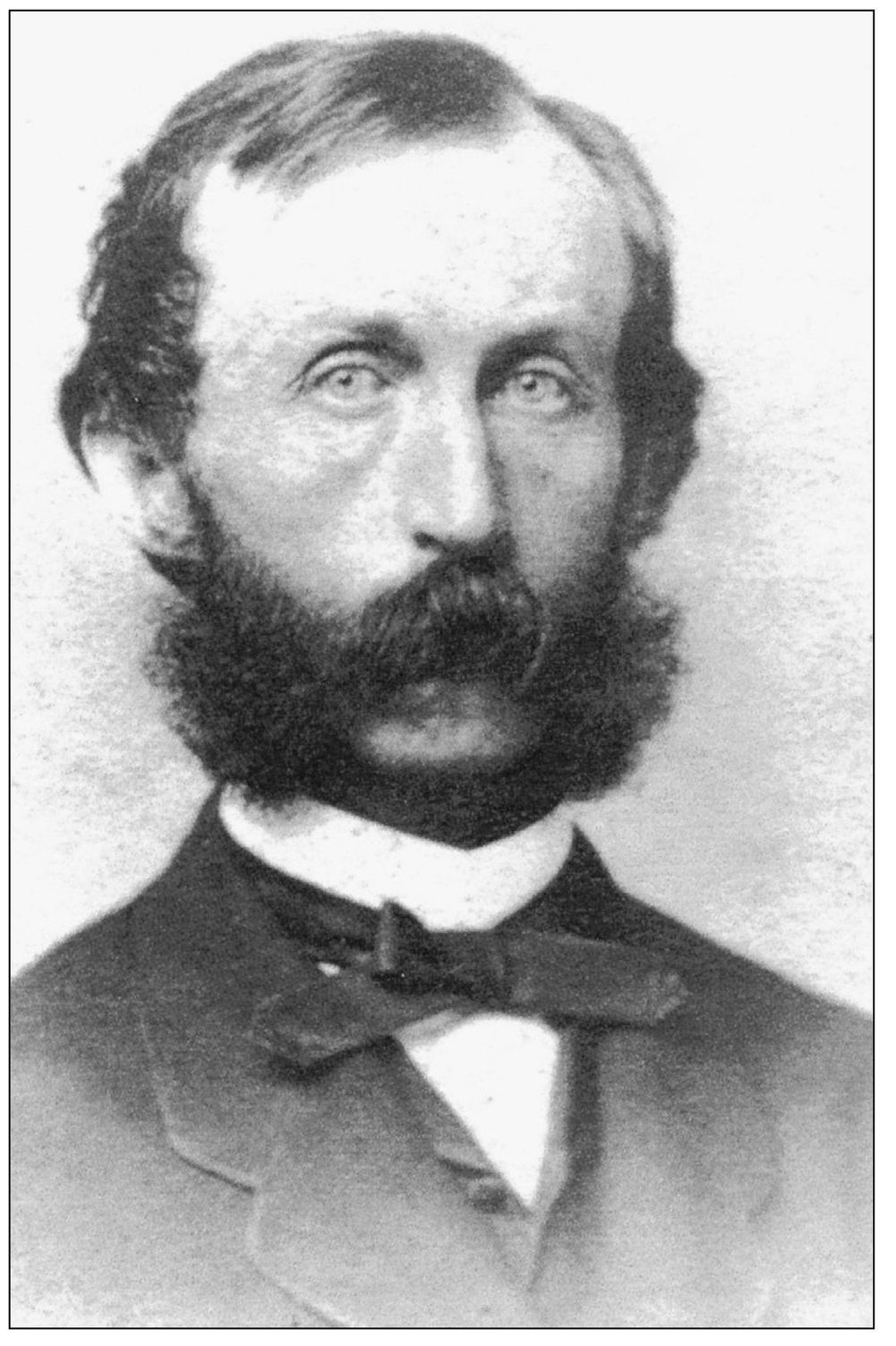

In addition to the Virginians posted on the south end of town, a small brigade of North Carolina cavalry under Brig. Gen. Beverly Robertson (left) took up a defensive position on the northern edge of the city. With fewer than a thousand men and horses, Robertson’s role was to keep the Union cavalry away from the wagon train and buy time until a stronger body of infantry could be brought into the fight. (Library of Congress.)

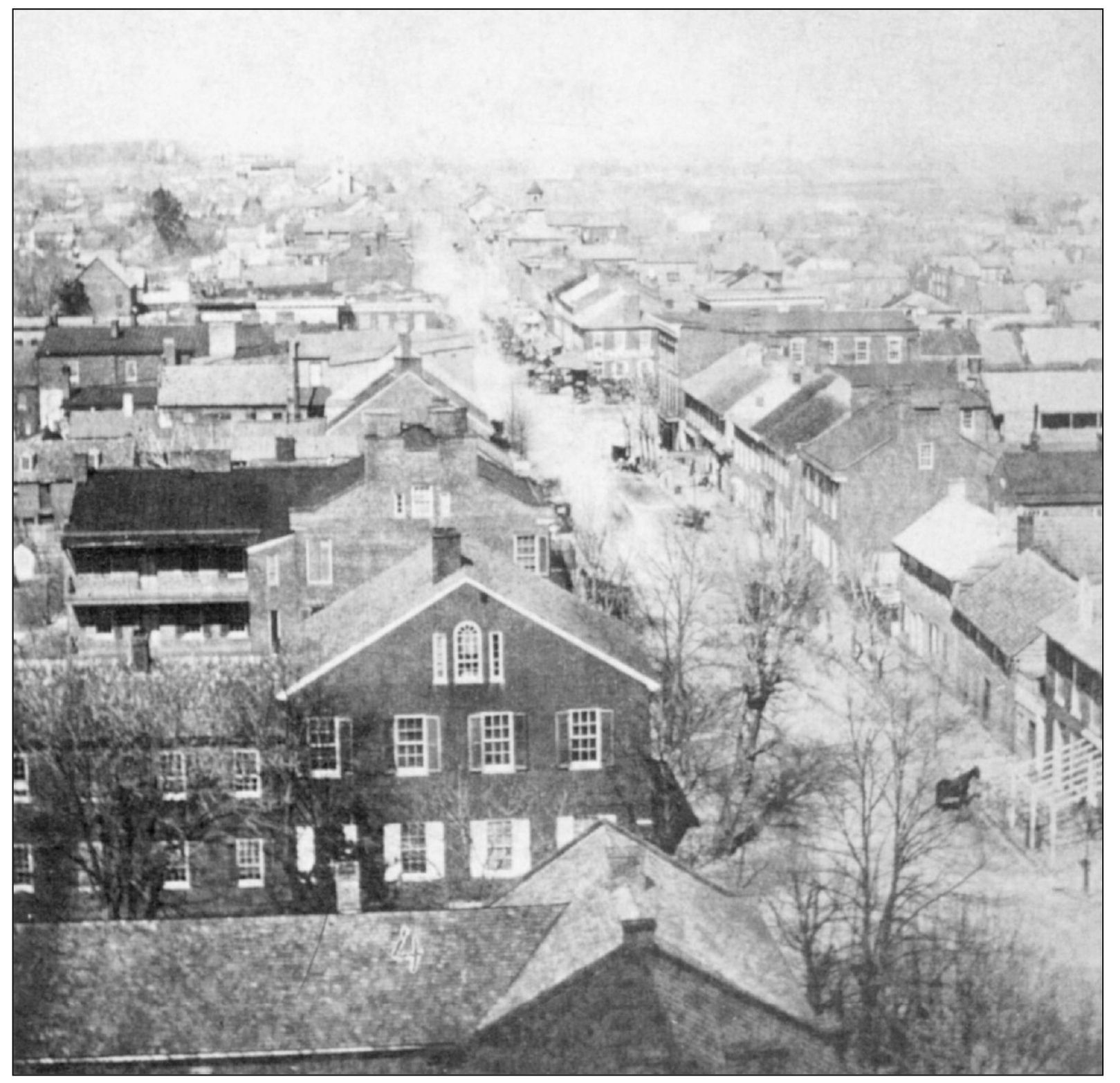

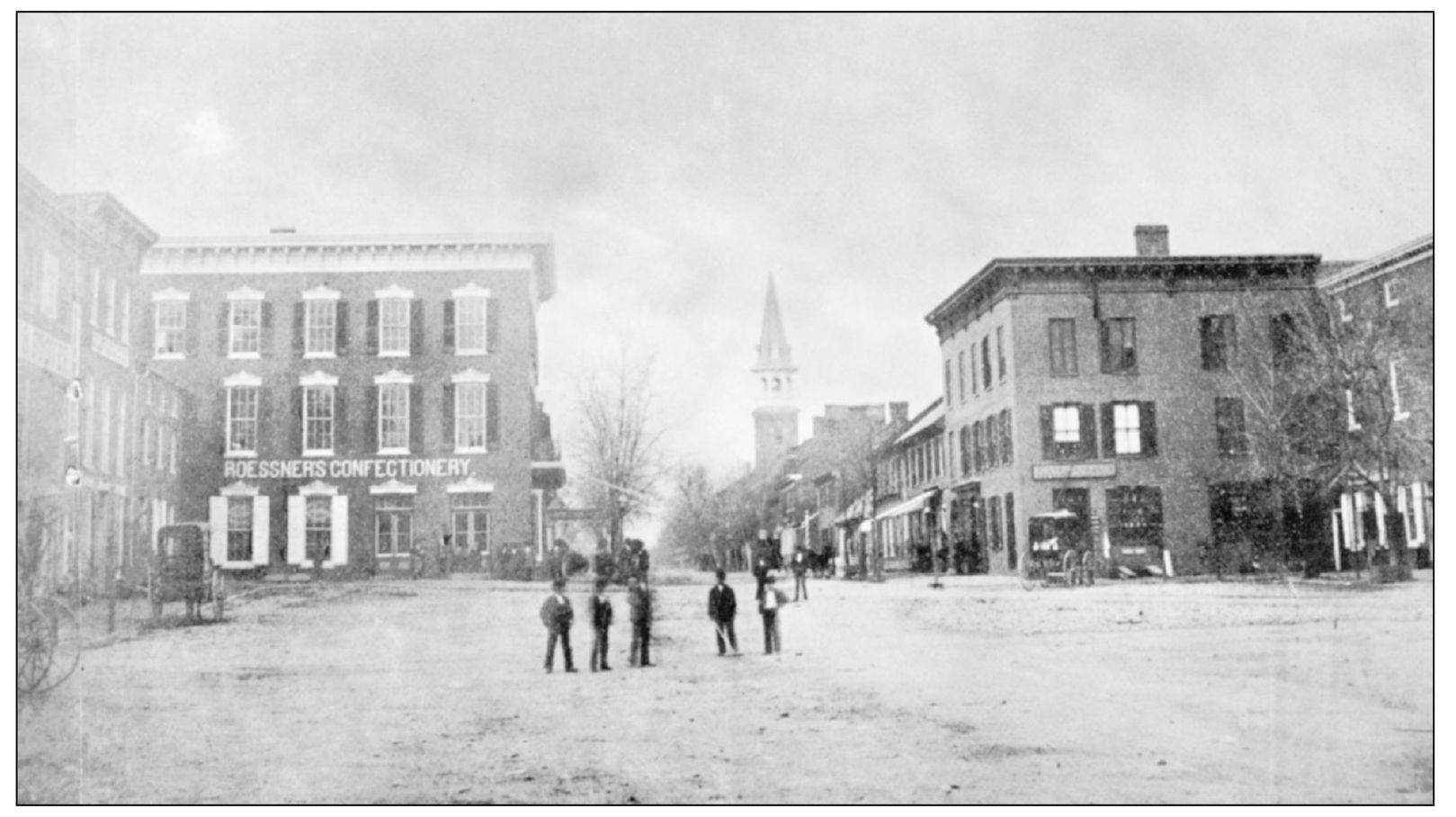

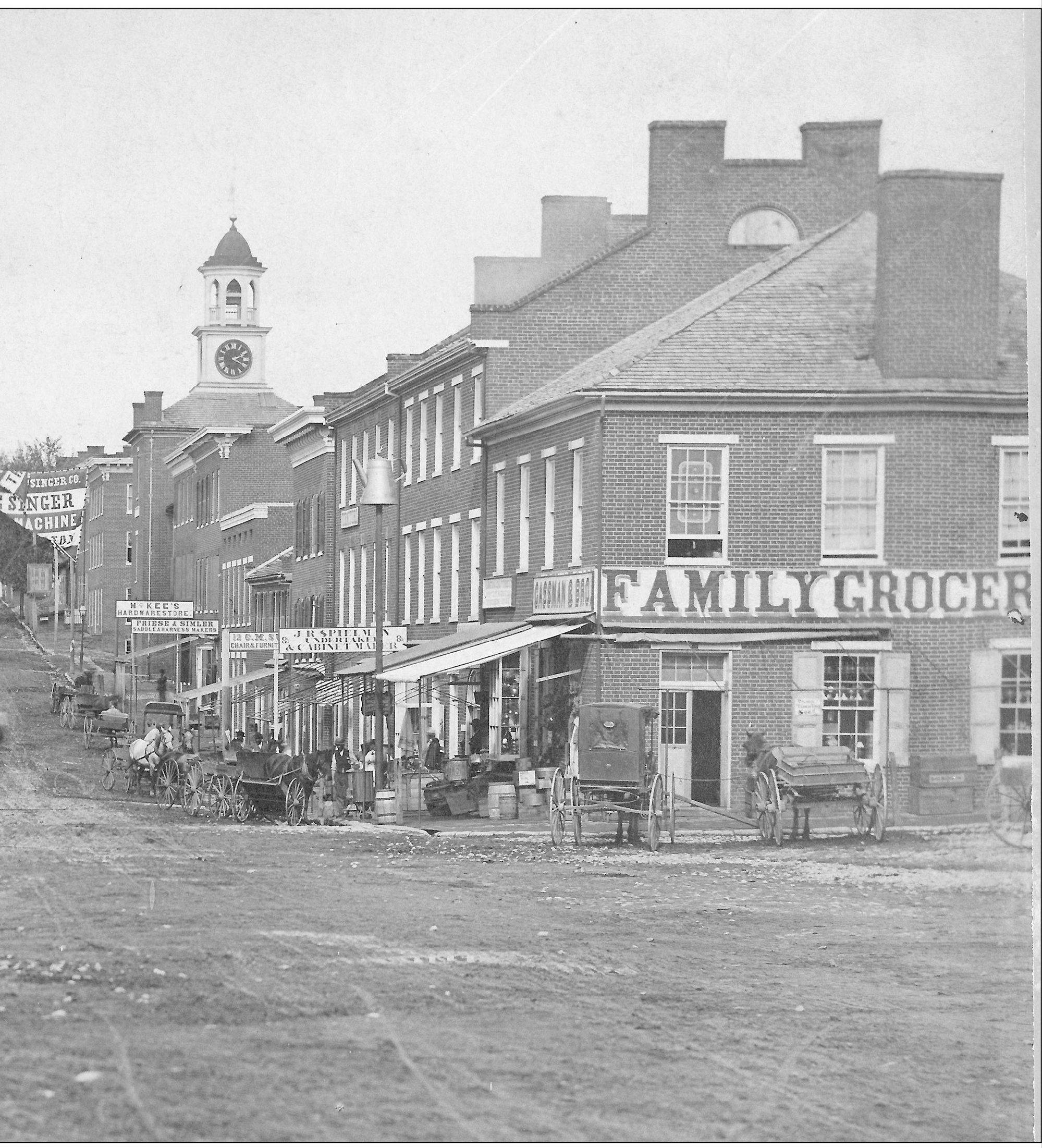

The rain-soaked and exhausted troopers of Chambliss’s and Robertson’s Brigades (the vanguard of the Army of Northern Virginia and guardians of the wagon train) entered Hagerstown from the north (rear center). Robertson took up position north of Public Square and Chambliss’s men built barricades just south of St. John’s Lutheran Church. This photograph was taken from the steeple of St. John’s just after the war. The barriers would have been behind the photographer. Arriving from Boonsboro, General Kilpatrick ordered an assault on the barricades. His men stormed north up South Potomac Street and breached the makeshift walls. The rebels were overwhelmed and retreated north and regrouped around Public Square. The commander at the barricades, Col. J. Lucius Davis of the 10th Virginia Cavalry was captured when his wounded horse fell and pinned him to the street. Yet he continued to fight while pinned beneath the horse. Nicknamed “Killcavalry” by his men, General Kilpatrick ordered his forces to pursue the rebels north on Potomac Street (in the center of this image), and a great cavalry clash occurred in and around Public Square. (WCHS.)

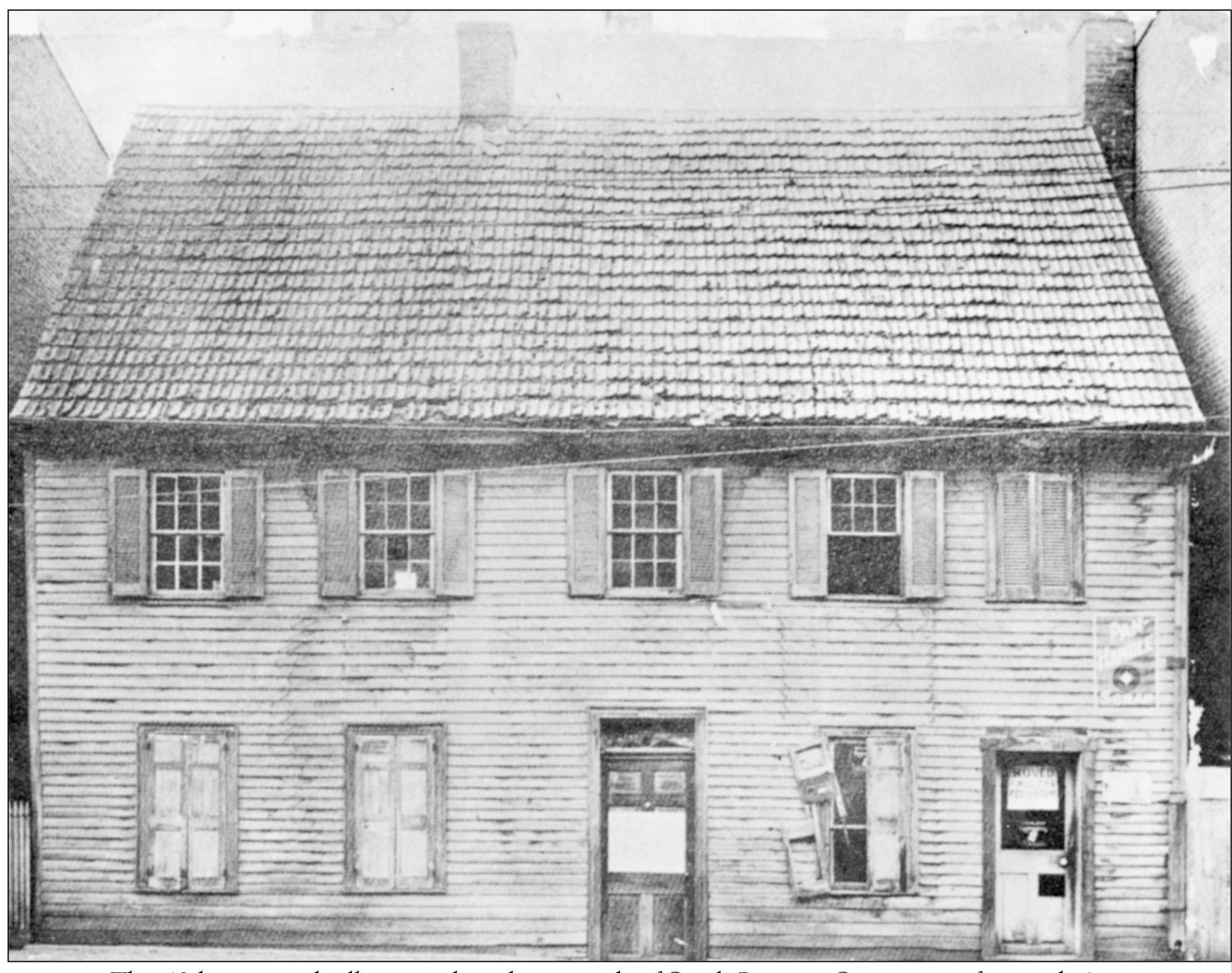

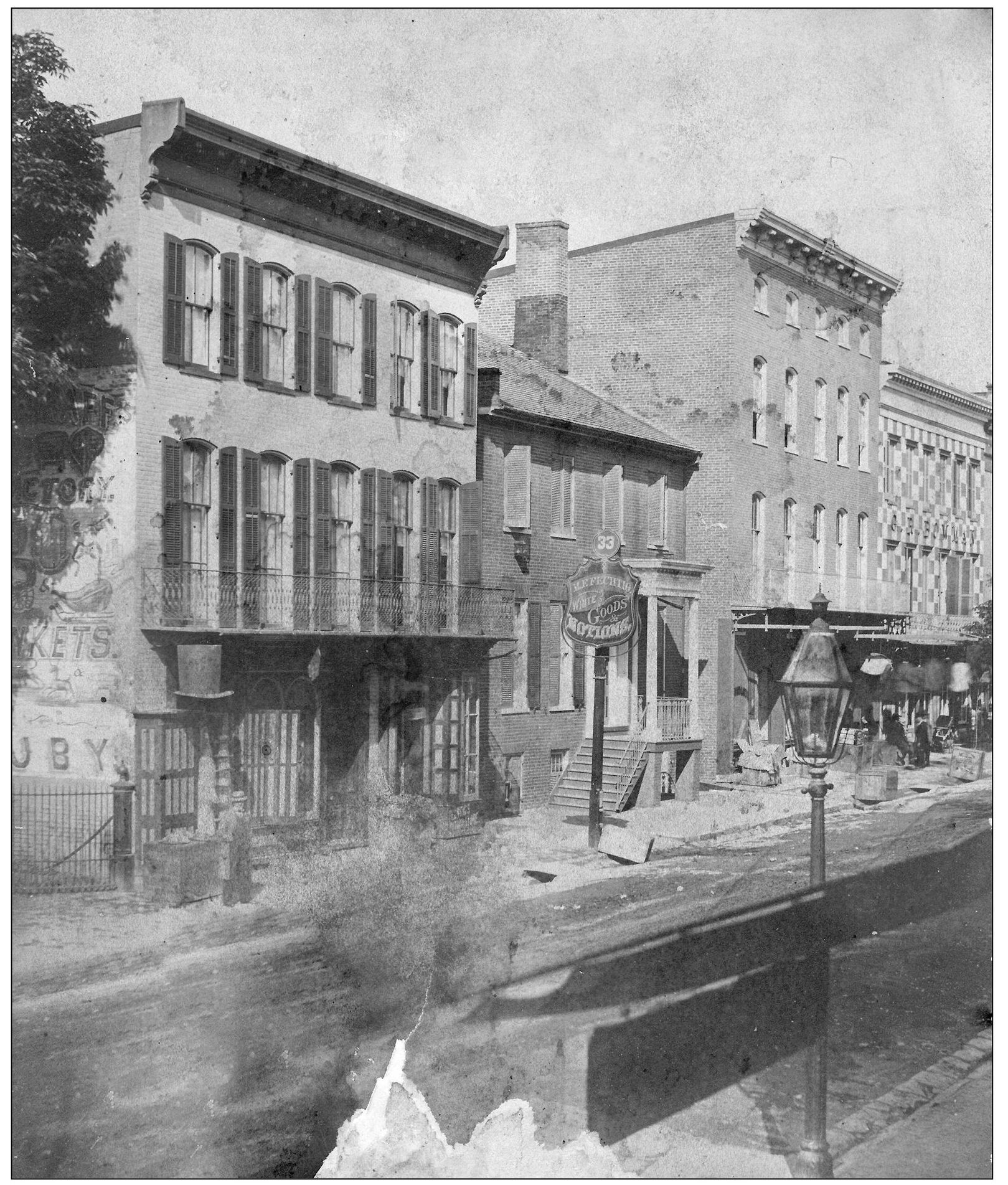

This 18th-century dwelling stood on the west side of South Potomac Street across from today’s Washington County Free Library’s central facility. It was demolished around 1912 to make way for an Odd Fellows Lodge that stands to this day. Countless soldiers marched past this house during the war; and in the battle on July 6, the cavalrymen of the 9th and 10th Virginia Regiments swept past its door with Col. Nathaniel Richmond’s Union troopers in hot pursuit. (Maryland Cracker Barrel.)

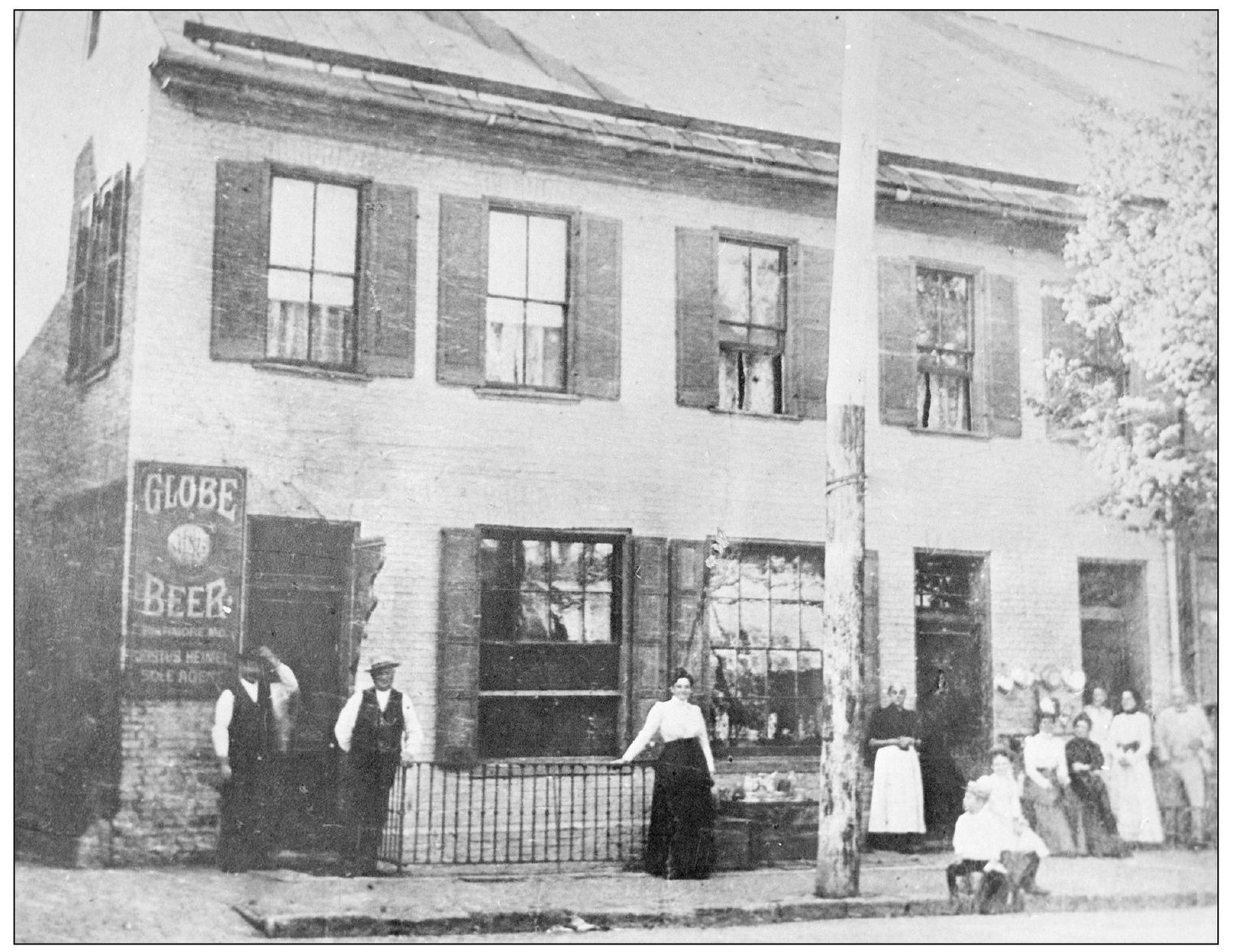

During the Civil War, Justus Heiml operated a store and brewery on his property on the west side of South Potomac Street. This site is located to the right of the Maryland Theater and is now occupied by a four-story apartment building. In this late 1800s photograph, Heiml’s brewery looks much as it would have to the blue and gray soldiers who fought their way up Potomac Street. (WCHS.)

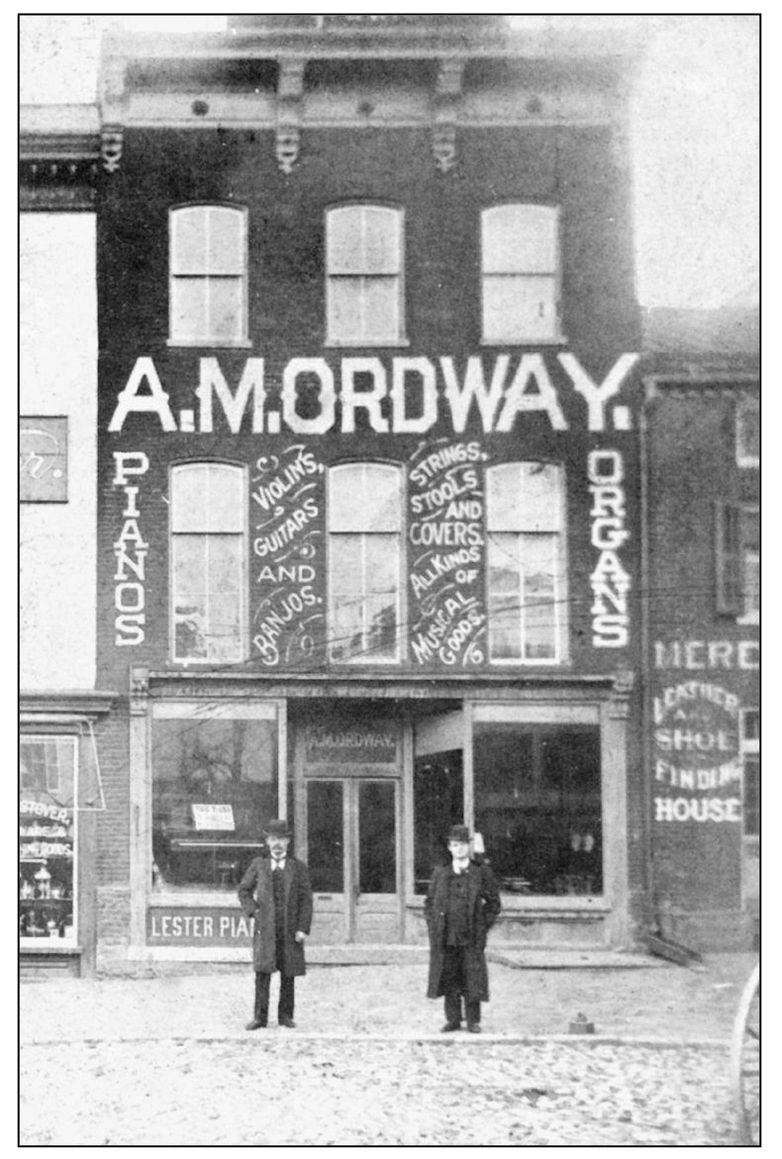

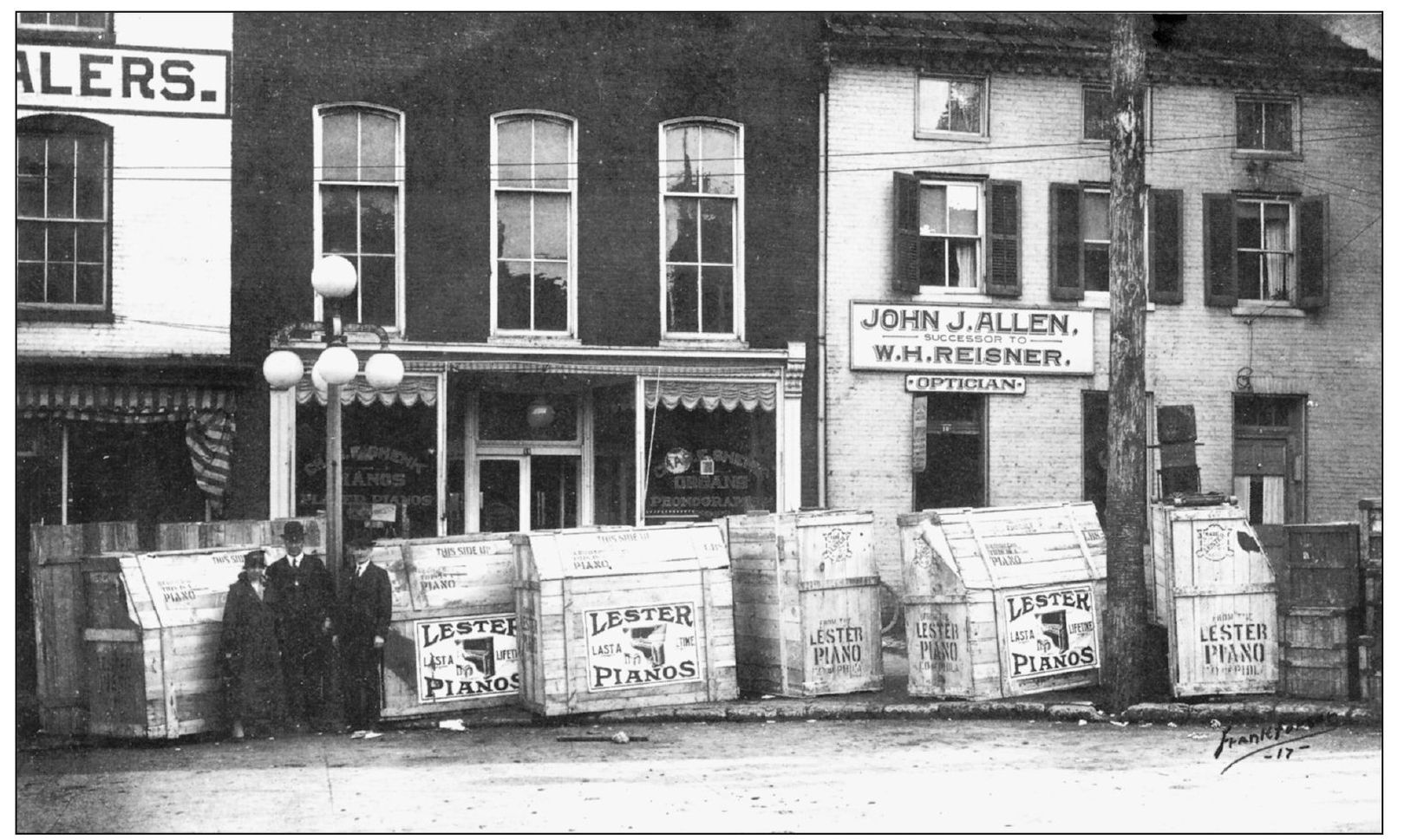

The building that later housed Ordway’s Pianos and Organs was located on the east side of Public Square in the late 1800s. The first two floors of this structure stood during the battle in the square; the third floor was added later. This site is now occupied by the Alexander House. (Maryland Cracker Barrel.)

The troopers of the 9th and 10th Virginia Regiments fled north from the church in the background. When their pursuers reached the square, 40 men from the 1st Maryland Cavalry crashed into the blue cavalry from West Washington Street (to the right). This checked the pursuit and afforded the Virginians time to regroup two blocks to the north. Andrew Hager operated a store on the site of Roessner’s Confectionery in 1863. (WCHS.)

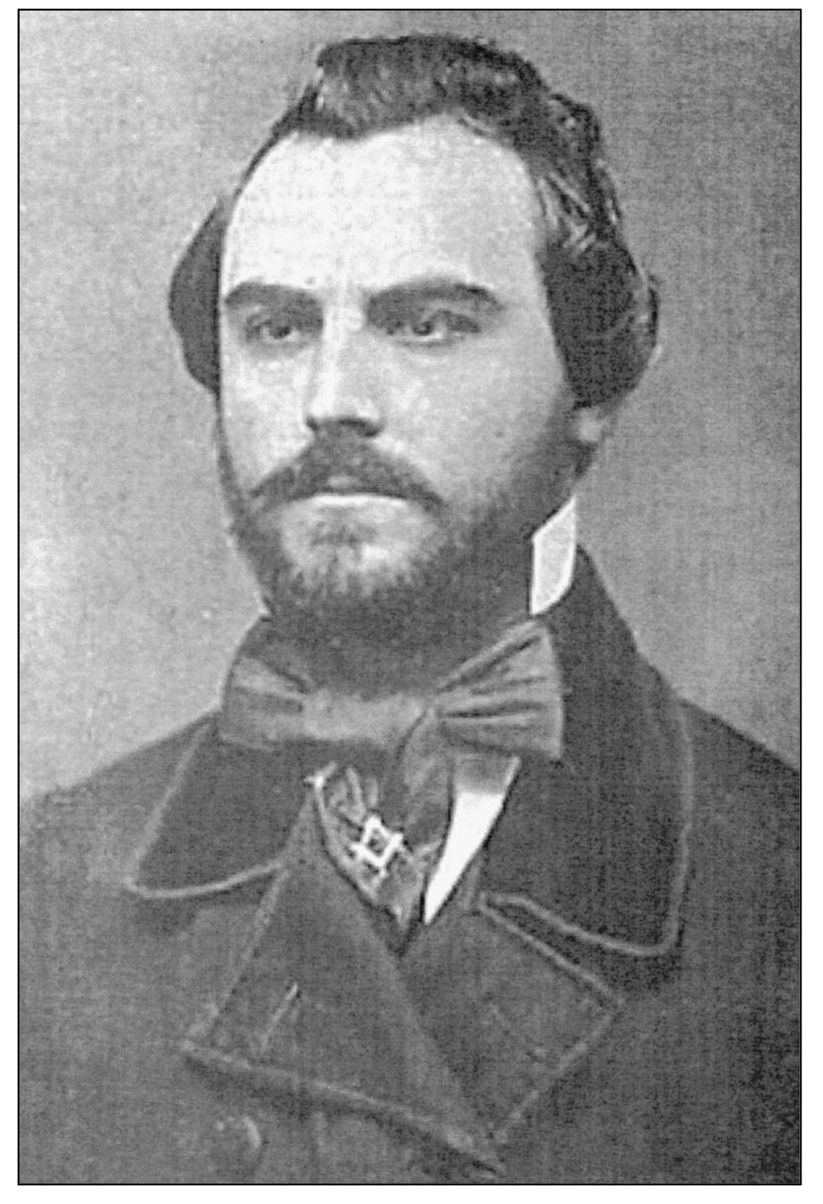

Capt. Frank A. Bond commanded the small band of Marylanders. Born in Harford County, he was a resident of Anne Arundel County. After the war, he became the warden of the Maryland House of Correction in Jessup and received a commission in the Maryland National Guard, rising to the rank of general. Bond was wounded in the leg later on July 6 in the pursuit of Kilpatrick’s men toward Williamsport. This wound would preclude further field service. He was serving on the staff of Gen. Collett Leventhorpe at the war’s end. (Dr. Mark Bond.)

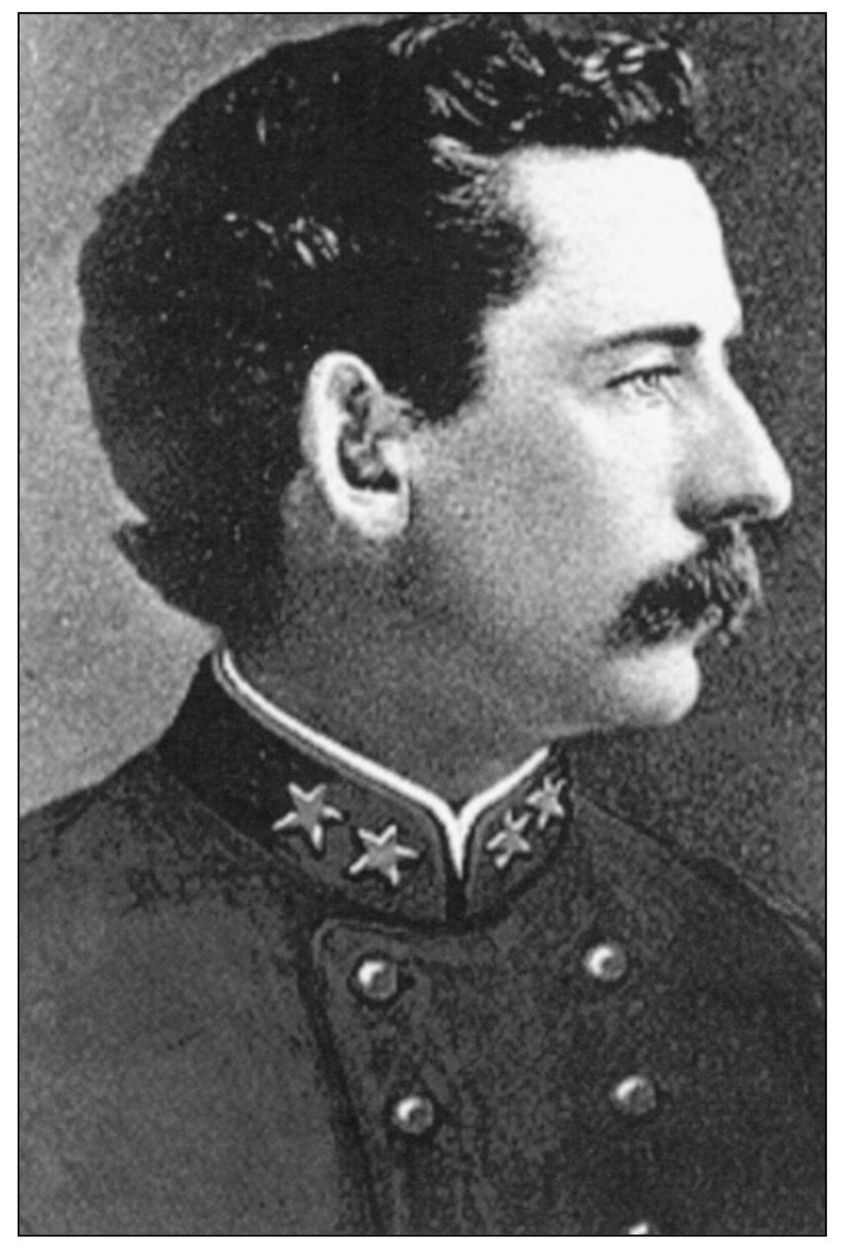

With the sound of the guns, Col. Milton Ferguson’s brigade rode hard from Chewsville to aid their fellow Confederates. Ferguson’s force entered the fray from Chewsville Pike (now Jefferson Boulevard) and took positions in the area of today’s city golf course. An artillery duel rocked the homes of Hagerstown to their foundations when a battery commanded by Capt. Roger Preston Chew of nearby Charles Town (left) unlimbered his guns and began shelling the arriving Union cavalry. (Author’s collection.)

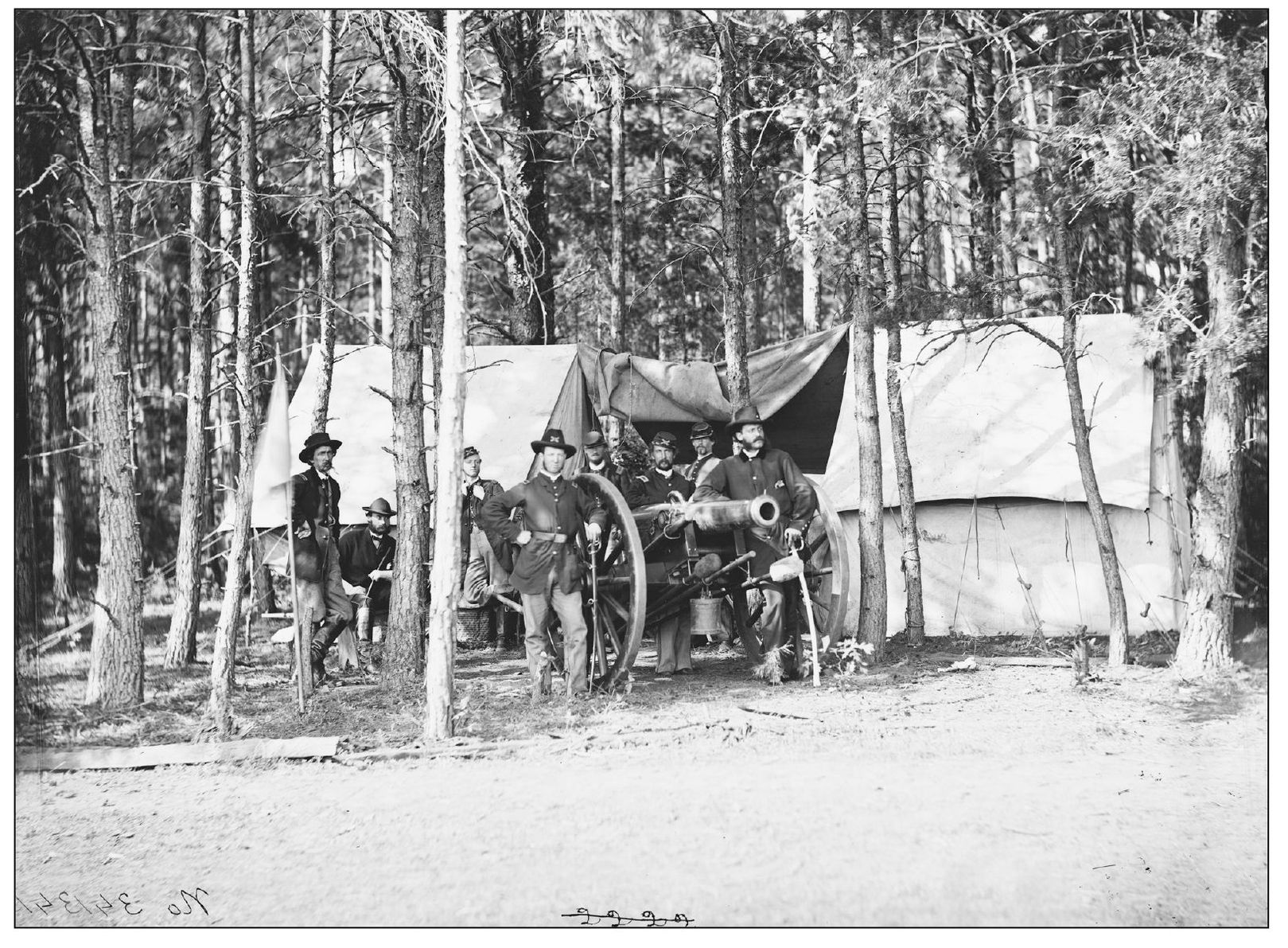

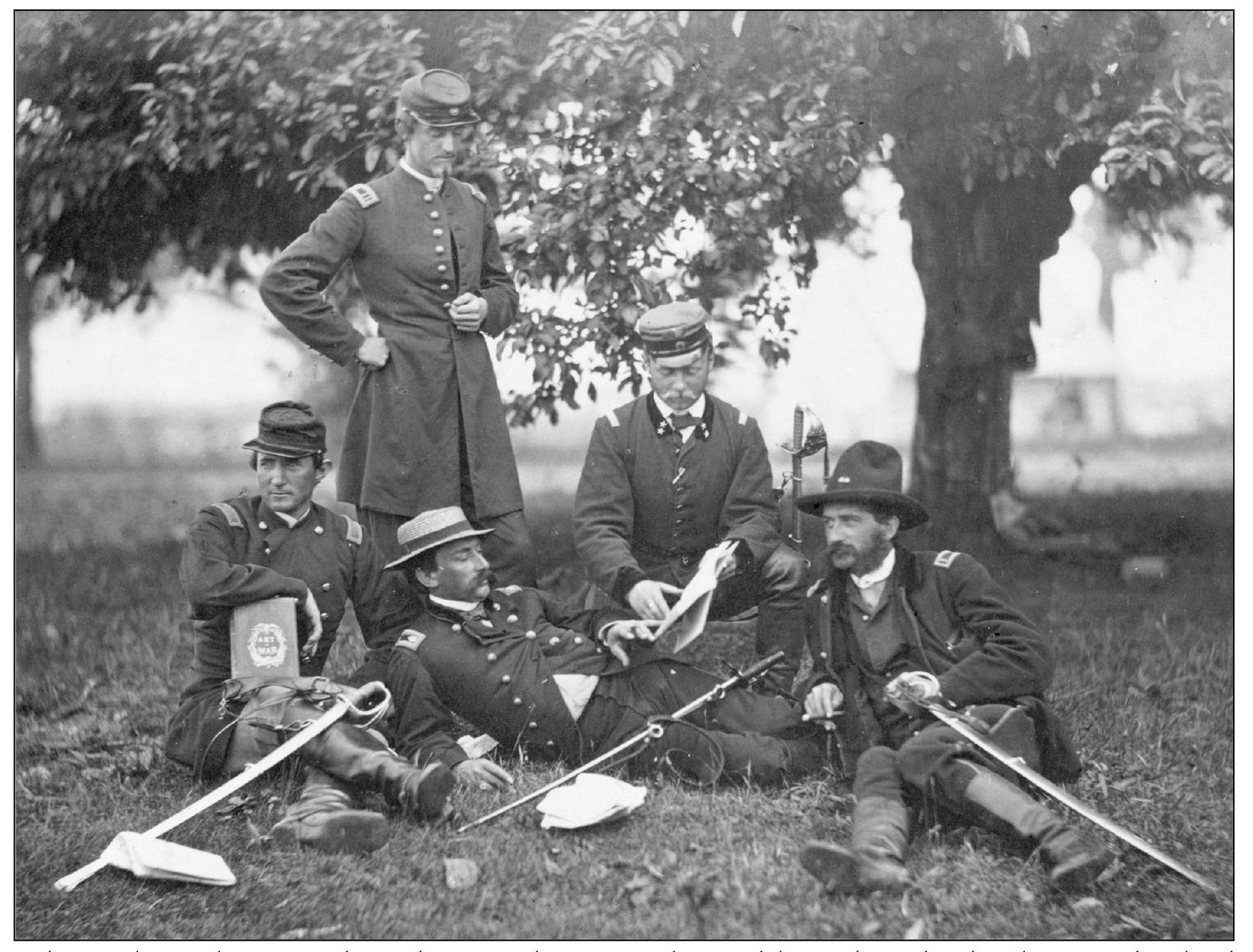

Battery E, 4th U.S. Artillery was ordered to the high ground on the north side of Kee Mar College. Commanded by Lt. Samuel Elder (standing far left), the troops dueled with Chew’s battery for about 30 minutes and fired into Ferguson’s force with grape and cannister (short range antipersonnel ammunition). Elder’s hilltop position was reinforced by elements of the 5th New York and 1st Vermont Cavalry Regiments. This photograph of Elder and his fellow officers was taken about six weeks after the battle. (Library of Congress.)

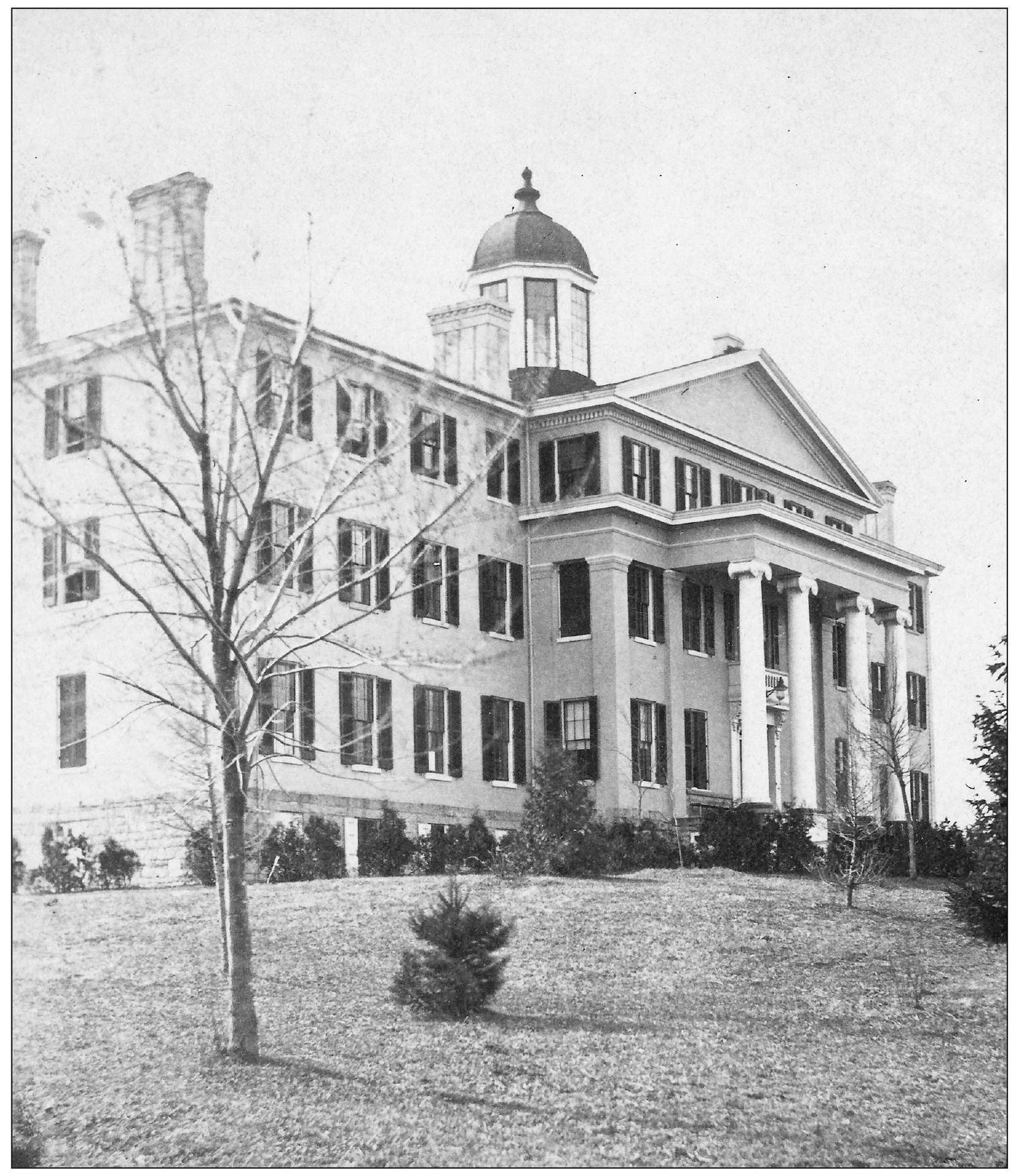

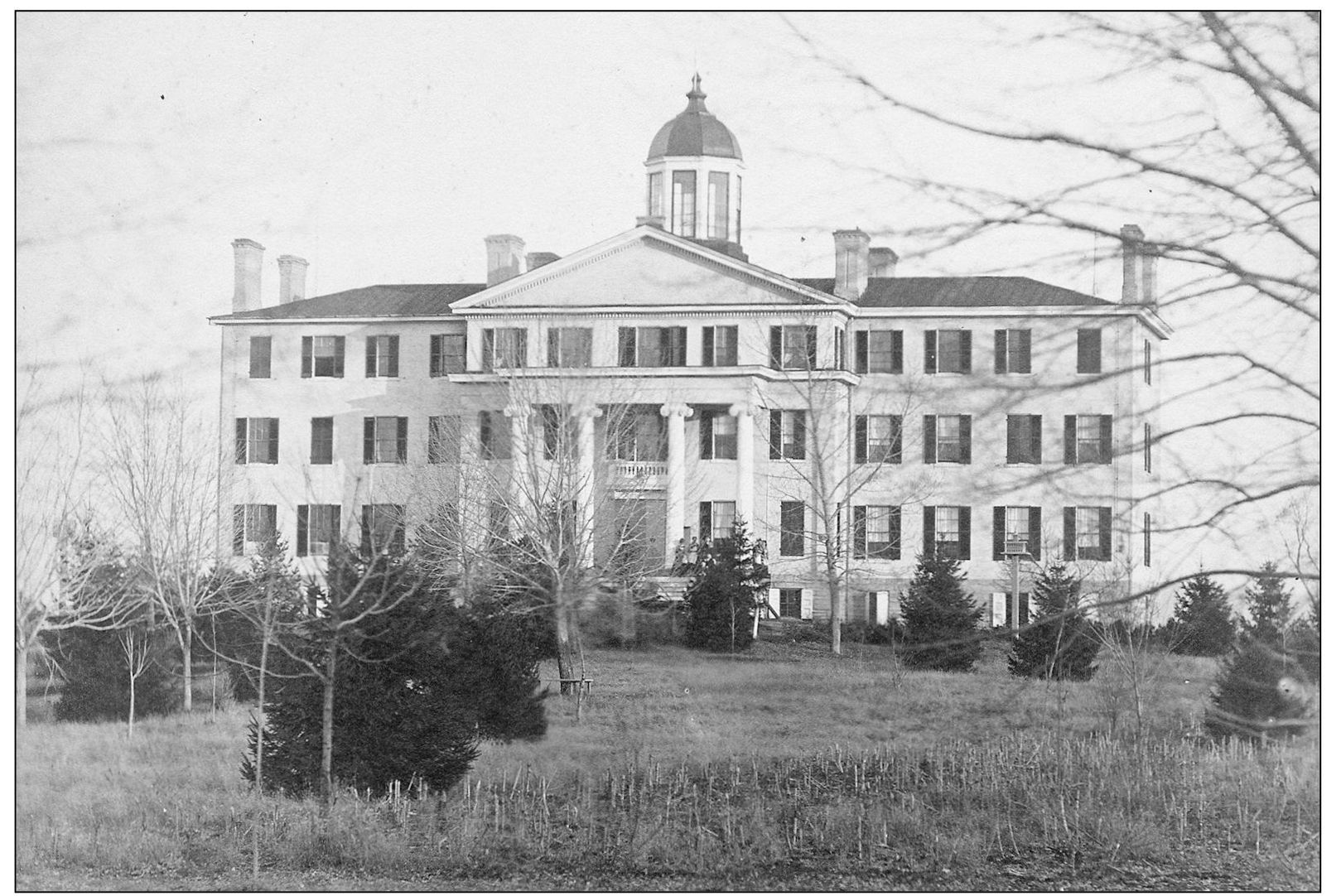

Kee Mar College occupied the heights at present-day King Street. Its elevation and minimal number of trees made the site optimal for placing artillery, as it commanded a sweeping view of the battlefield. Although the Confederates were on the defensive in town, Ferguson’s brigade arriving from Chewsville was on the offensive. However, the commanding location enabled Elder’s battery and its cavalry support from the New Yorkers and Vermonters to fend off several attacks and attempts to swing around the right of the Union line. After the Battle of Hagerstown, the college was once again commandeered for military use as a field hospital. (WCHS.)

When Kilpatrick prepared another assault, Capt. Ulric Dahlgren (standing) volunteered to lead it. He dismounted 20 men from the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry and the small force made its way up Potomac Street toward the square, 10 on each sidewalk and Dahlgren riding in the street. They reached Franklin Street before fire from a church and the Oak Spring to their left (west) checked their advance. Dahlgren was shot in the right ankle. He is shown here about a month before the battle. Kneeling next to him is Prussian count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, who later popularized air travel in dirigibles. (Library of Congress.)

The walls and fences around Oak Spring (now the location of the Pioneer Hook and Ladder Company) and an adjacent church provided Confederates excellent cover from which to fire into the left flank of the attacking Union cavalry. This image is taken from Franklin Street looking south toward Washington Street (WCHS.)

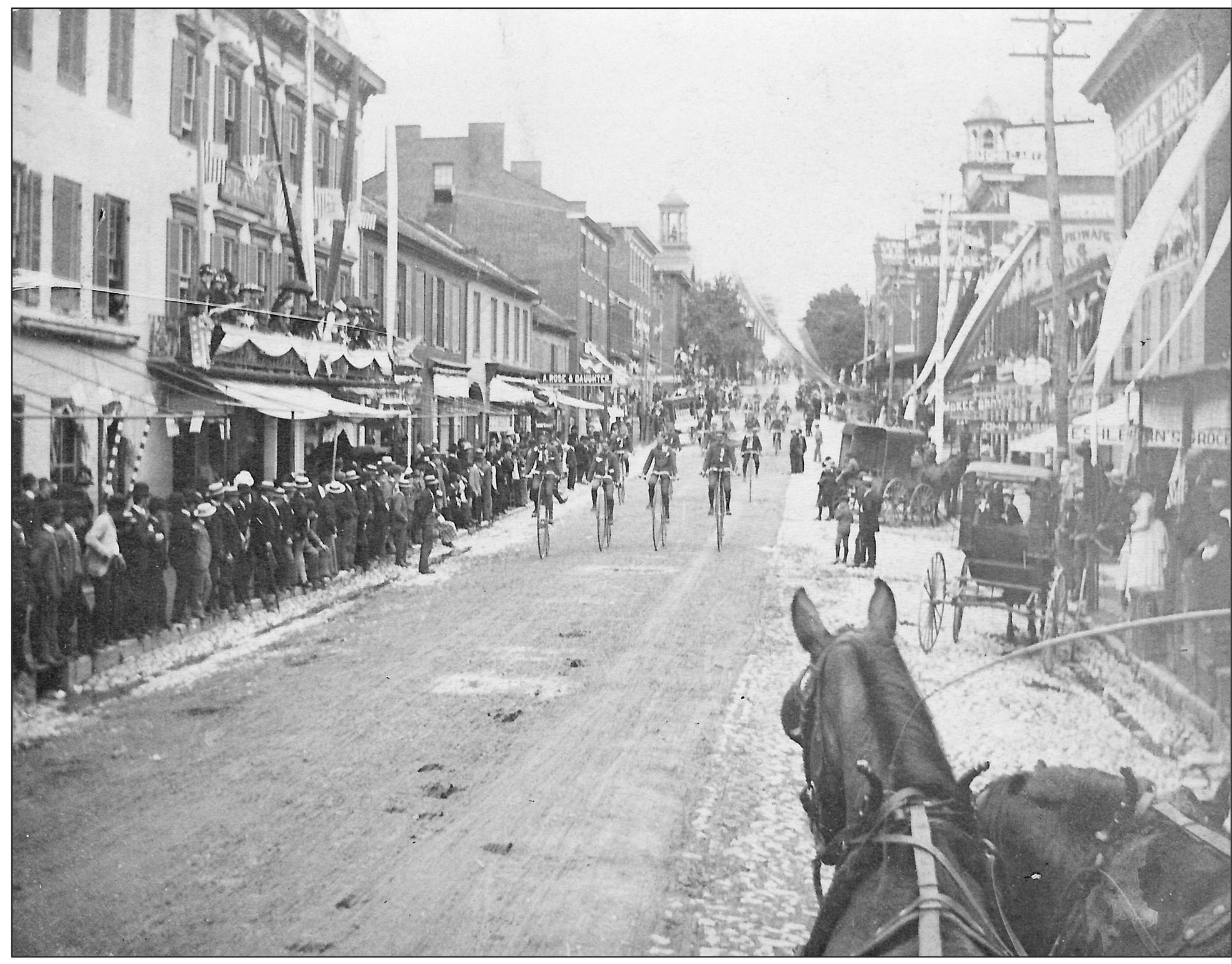

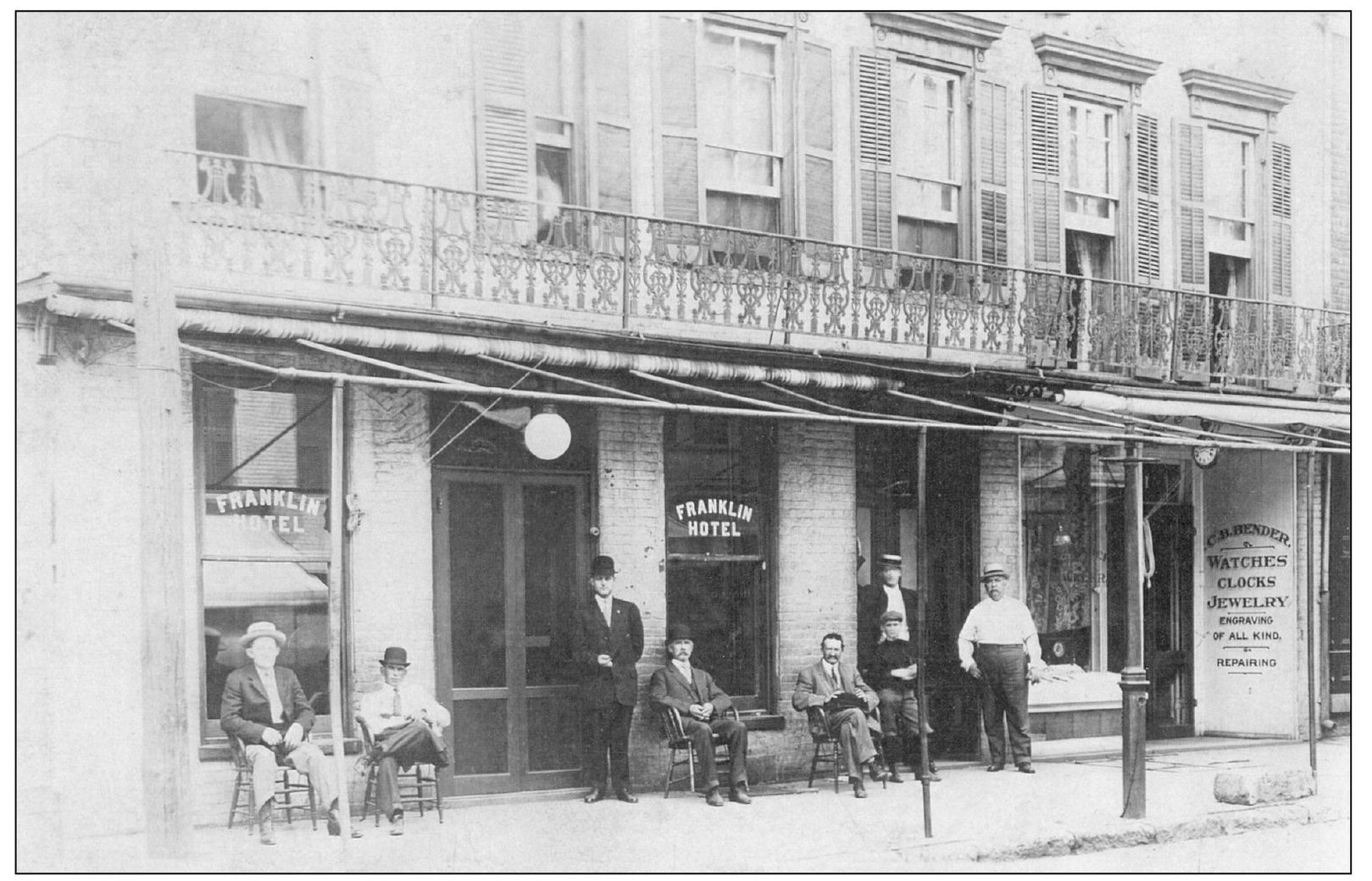

The 20 troopers from the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry who charged up the sidewalks of North Potomac Street would have encountered this view, minus the wheelmen and throngs of spectators. This early 1880s image from a wheelmen’s convention shows a streetscape little changed in 20 years. The Franklin Hotel can be seen at left, as well as the cupolas of the Independent Junior Fire Company (left) and Hagerstown Town Hall (right). To the right of the photograph, a sergeant was struck down in the service of his country when an unidentified Hagerstown woman fired at the troops from an upper window. (WCHS.)

This faded stereograph image from the late 1860s or early 1870s places the viewer in the boots of the Confederate cavalrymen as they watched Kilpatrick’s Union horsemen storm up Potomac Street into the city. The gallant Captain Dahlgren was wounded in the area shown in the right foreground of this photograph. The town hall is conspicuous on the left, with the spire of St. John’s Lutheran Church visible in the distance. (WCHS.)

The Oak Spring Church was constructed in 1855 on the south side of West Franklin Street between Potomac Street and today’s Pioneer Hook and Ladder Company building. It served as a good barrier to shield Confederate marksmen shooting into the Union cavalry advancing up Potomac Street past the town hall. The church congregation relocated farther west on Franklin Street in the late 1800s; it is now Christ Reformed Church. (Maryland Cracker Barrel.)

The residence of Dr. James B. McKee near the Independent Junior Fire Company was approximately the farthest point north to which Union cavalry advanced. With flanking fire from the Oak Spring and an opponent taking full advantage of the tall wall at Zion Reformed Church, the Union advance stalled in the face of numbers, superior position, and geography. (WCHS.)

As Union soldiers fell, they were hurried by their comrades and local men into nearby buildings such as the Franklin Hotel. The hotel served as a hospital at times throughout the war and was situated where the North Potomac Street parking deck is located today. (Roger Keller.)

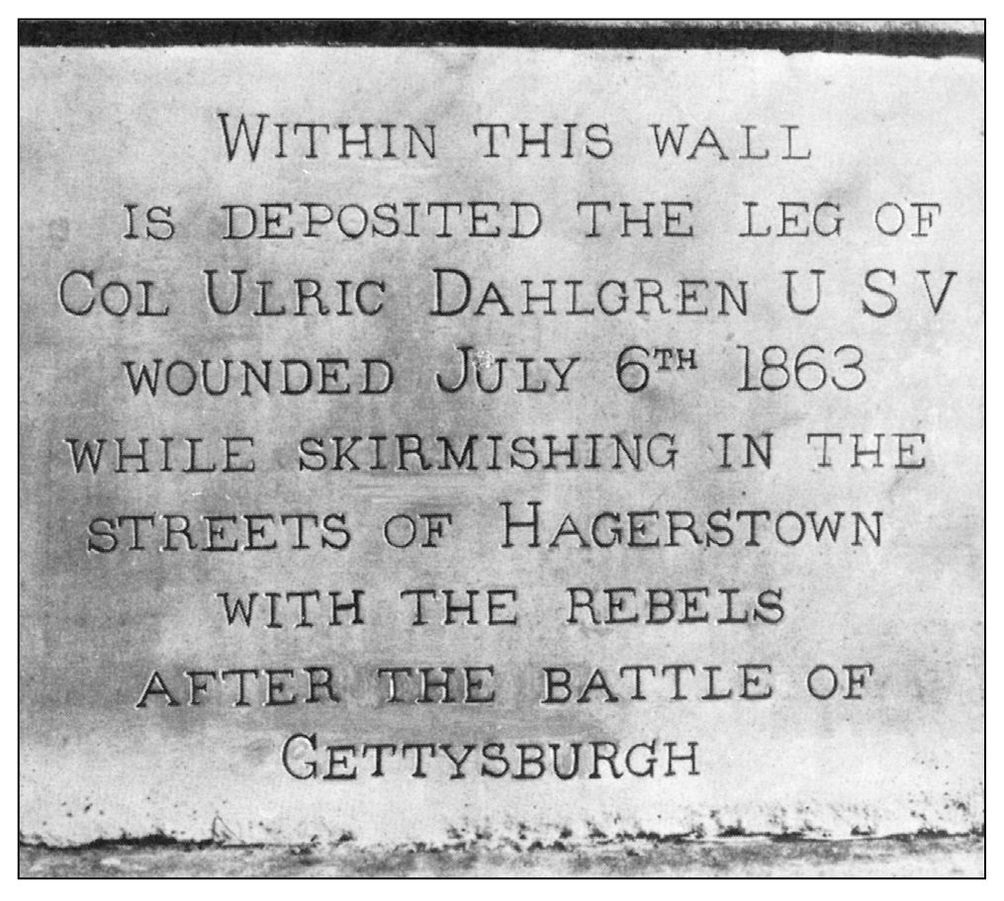

Captain Dahlgren was taken to his father’s home in Washington. Gangrene set in, and the foot had to be amputated at the lower leg. An admiral in the U.S. Navy, Dahlgren’s father had the leg buried in the wall of a building at the Washington Navy Yard. Captain Dahlgren was promoted to colonel and was killed in a raid on Richmond on March 2, 1864. Controversy ensued when Confederates found orders on his body that called for burning the city and assassinating Pres. Jefferson Davis and his cabinet. His father spent the rest of his life trying to clear Ulric’s name. (Maryland Cracker Barrel.)

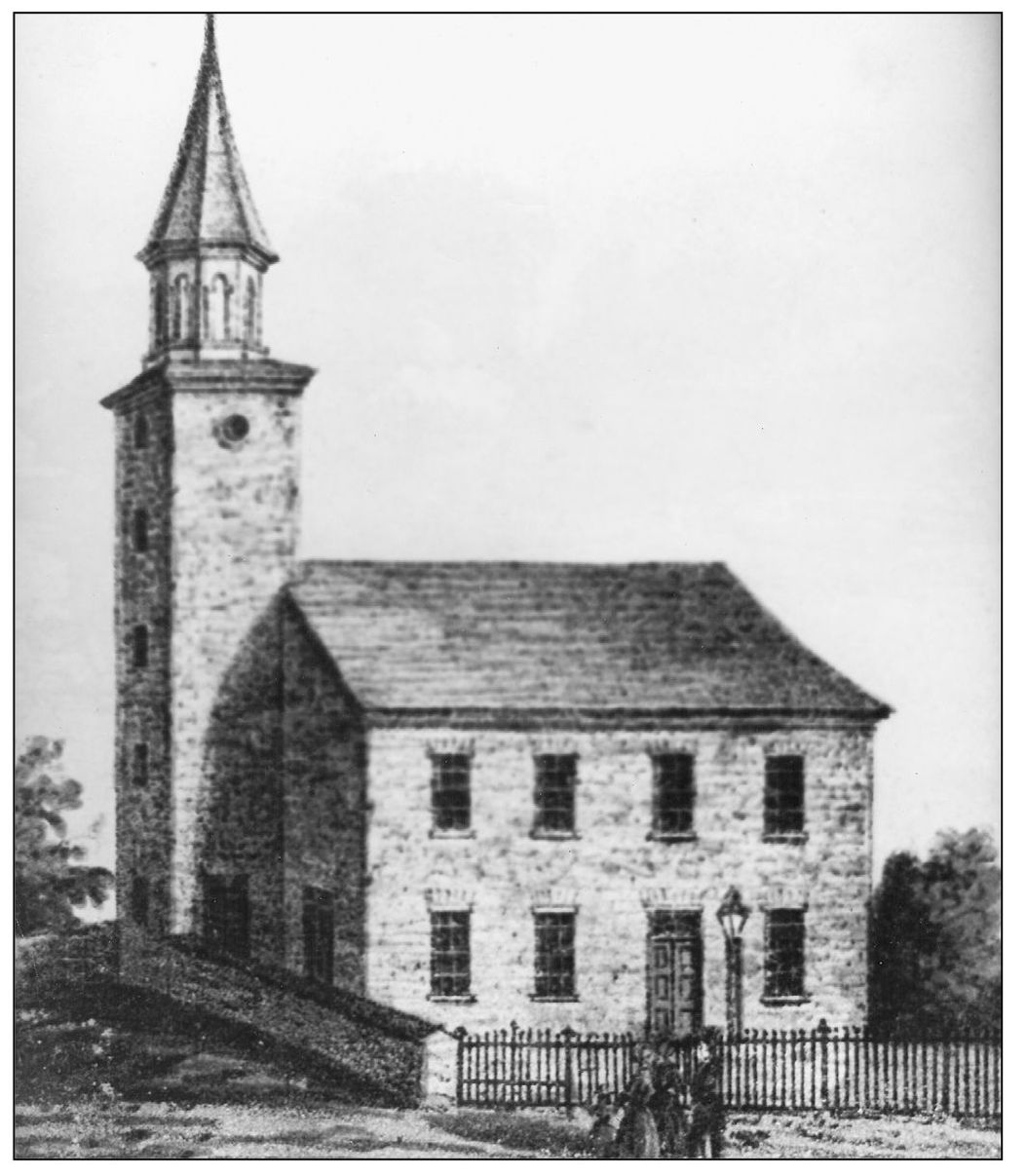

Zion Reformed Church was constructed in the 1770s. The Confederate defensive line took full advantage of both the church’s placement on a hill and the stone retaining wall that runs along West Church Street to create an impenetrable barrier to the attacking Union horsemen. After the Confederates evacuated town a week later, Gen. George Custer observed Confederate movements from the steeple. A sharpshooter’s bullet is said to have ricocheted off of the church bell, nearly cutting Custer’s career short. (City of Hagerstown.)

The actions of Chambliss and Robertson and the little band of Marylanders bought time for a brigade of North Carolina infantry under Gen. Alfred Iverson (left) to hurry to the front and develop a defensive position at Zion Church. Iverson also sent men forward to occupy houses and buildings in the block between the church and town hall to create sniper’s nests. With this development and Col. Ferguson making progress at Kee Mar College, Kilpatrick withdrew his forces and moved to reinforce another Union brigade attacking Williamsport. (Library of Congress.)

This photograph of North Potomac Street in 1867 is believed to be published here for the first time. The streetscape is little changed from the great cavalry battle four years earlier. Captain Dahlgren’s 20 troopers ran up the sidewalks seen here toward the Confederates awaiting around Zion Reformed Church. The church was reconstructed to its current appearance in 1867. This image shows scaffolding erected to dismantle its pre–Civil War steeple. The weather vane Little

Heiskell, which appears on page 2, can barely be seen as a ghostly image above the ball at the top of the cupola of the Hagerstown Town Hall. The 1818 town hall was demolished in the 1930s to make way for the current city hall. Captain Dahlgren was wounded in front of this building at the intersection of Potomac and Franklin Streets. (WCHS.)

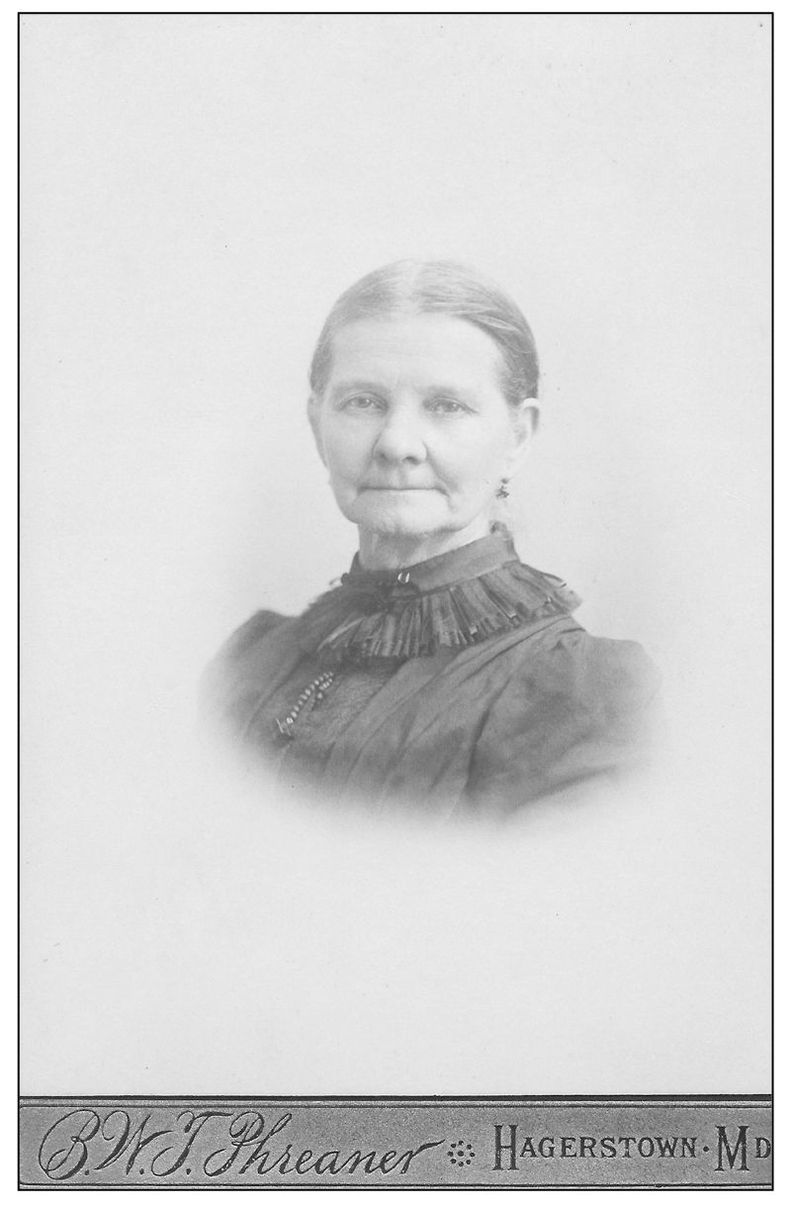

In the preparation of this book, the following note was discovered on the back of this c. 1890 image of Margaret Greenawalt at the Washington County Historical Society: “waived the flag over retreating Confederate soldiers and was roundly cursed as they sped up West Washington Street while her sister, Mrs. Bowman pulled at her skirt and begged her to come in saying ‘they’ll shoot you Maggie, they’ll shoot you!’. Miss Margaret was standing on the iron balcony where the hardware store is now - then bakery - waving the flag to the soldiers in blue just coming through the square below.” Is it possible Hagerstown can boast of its own Barbara Fritchie? (WCHS.)

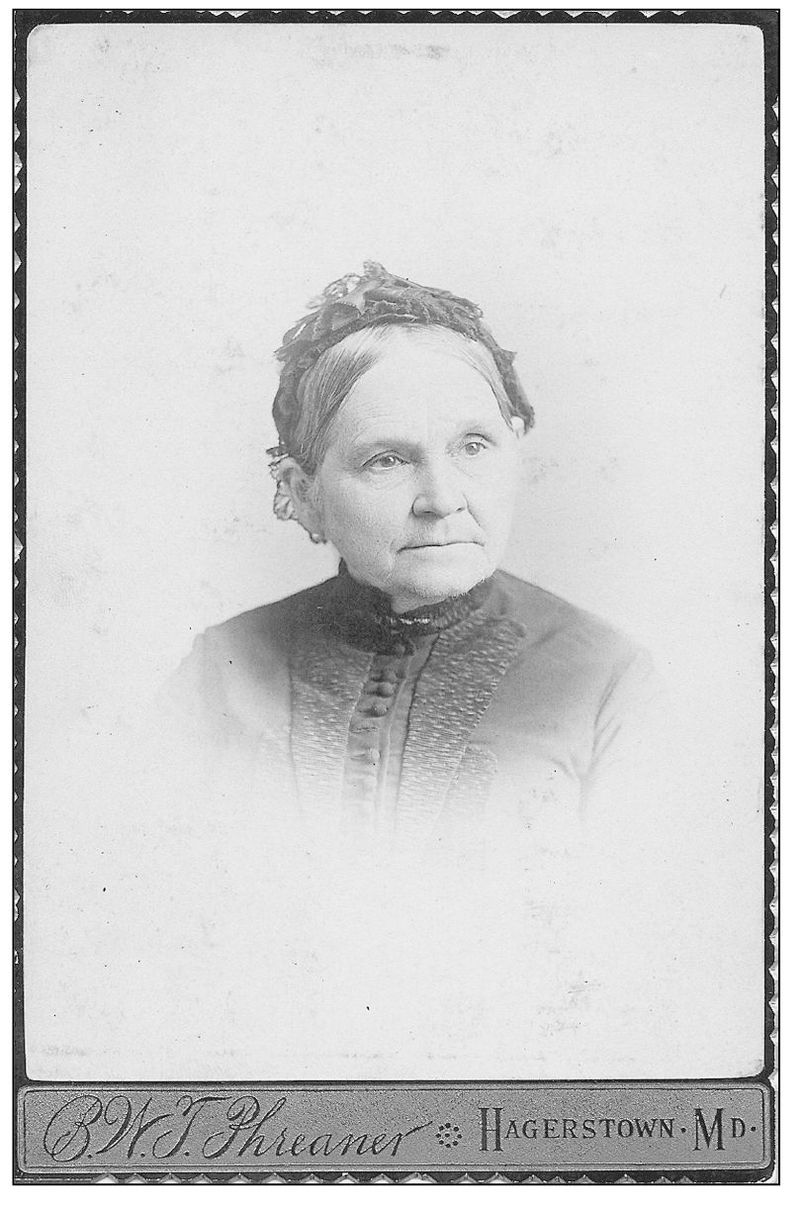

Myra L. McDade (the author of the note on the back of Maggie’s photograph) wrote the following on the back of this image of Mrs. Bowman: “told me the story of her sister several times when I was 12 years old.” Catharine and George Bowman ran a successful confectionery and bakery business on West Washington Street from the 1850s to the 1880s. Maggie lived with them. The Bowmans retired in the 1880s and purchased a house on Broadway, and Maggie stayed with them. After Catharine passed away in 1906, Maggie moved to Yonkers, New York, to live with Clyde Furst, her grandnephew (Catharine’s grandson) until she too passed in 1911. These photographs were taken about 30 years after their encounter with the Confederate army. (WCHS.)

Since the only time Confederates “retreated” through town was after Gettysburg, Maggie’s brave act likely occurred during the street battle in July 1863. This 1862 image by Elias Recher shows the George R. Bowman Confectioners and Bakery on the south side of West Washington Street. It is the checkered building at the extreme right. This is the building on which Bowman kept his telescope and observatory (mentioned on page 53). The Updegraff hat store building on the left still stands. (WCHS.)

Col. Samuel Lumpkin of the 44th Georgia Infantry was wounded on the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg. His leg amputated, Lumpkin was loaded into a wagon and endured a horrific, rain-soaked journey to Hagerstown. Col. Lumpkin died at the Kee Mar Army Hospital in September and was buried at the Presbyterian church on South Potomac Street (now the Fundamental Baptist Church). When the cemetery was removed, his remains were taken to Washington Confederate Cemetery. His is one of the very few individually marked graves at the Confederate cemetery. (Richard Clem.)

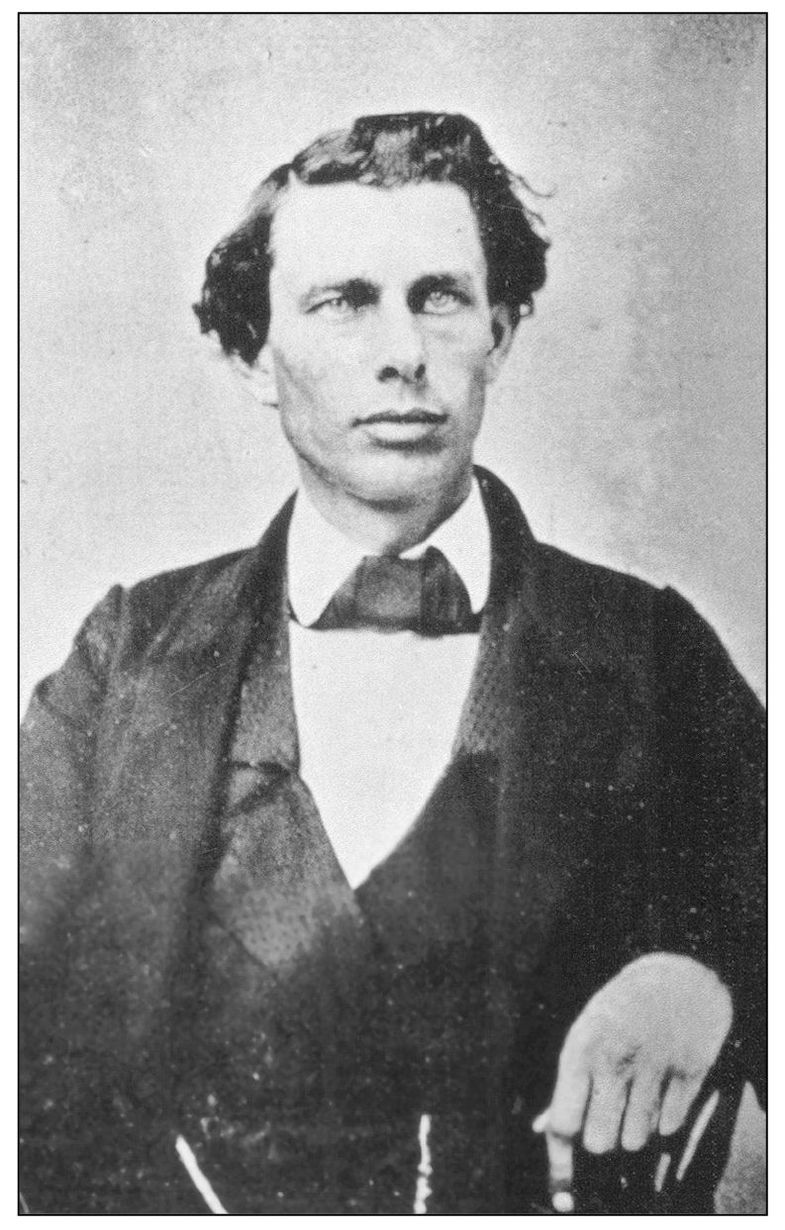

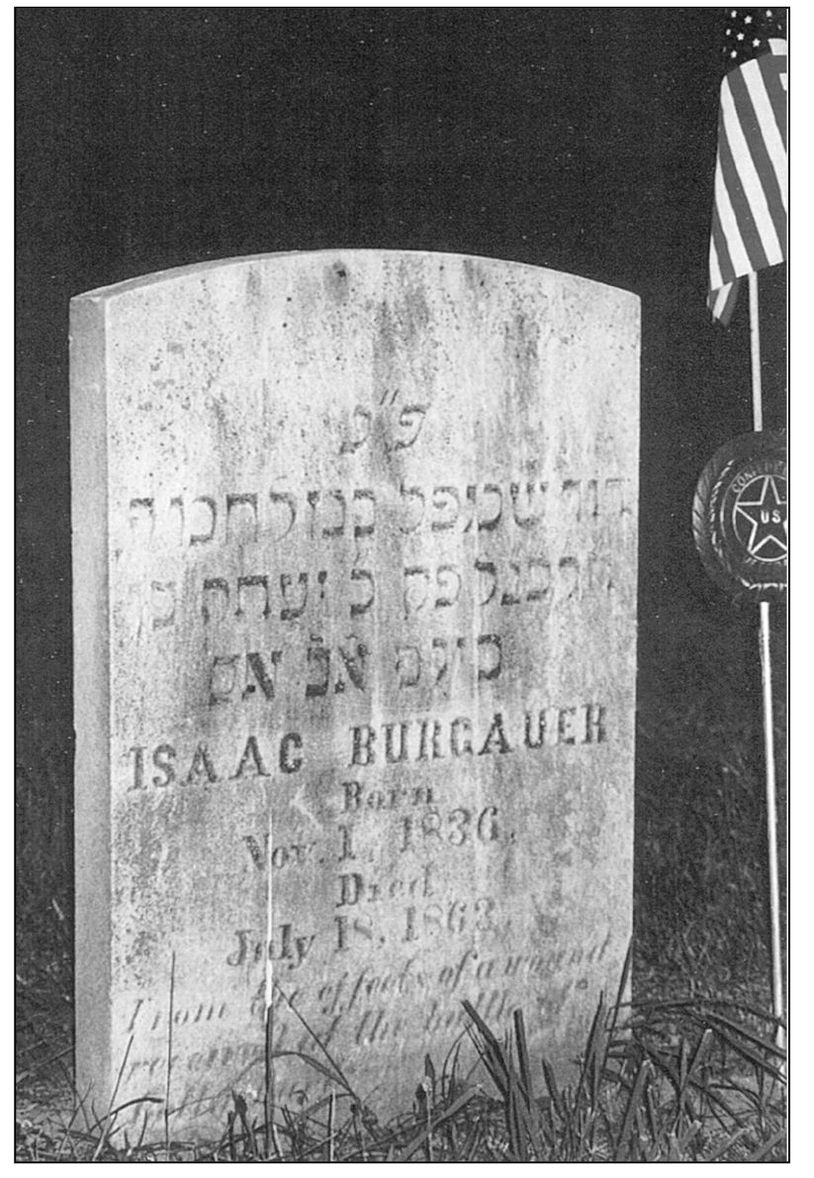

Lt. Isaac Burgauer, 3rd Arkansas Infantry, was wounded at Gettysburg and transported to Hagerstown. When he died on July 18, his last request was that he be buried in a Jewish cemetery in accordance with Jewish custom. The Israelite Benevolent Society of Hagerstown collected funds to have his remains prepared and taken to the Jewish cemetery in Chambersburg. Levi Stone transported the rebel lieutenant in his carriage to his final resting place in Pennsylvania. (Jim Wolfson.)

Van Wilson was a resident of Fayette County, Alabama, at the outbreak of the war. He enlisted in the Sumter Light Guards, a cavalry company that later mustered into Mississippi state service and became Company D of the Jeff Davis Legion. His brother served in an Alabama infantry regiment and died in the service of the Confederacy in the Peninsula Campaign of 1862. Van survived the carnage at Gettysburg only to be killed in action in Hagerstown during the retreat toward the Potomac. (Frances L. Brasher.)

Cpl. Lawrence Feigenschuh served in the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry and was captured by the Confederates in Hagerstown on July 6. His company was involved in the repeated charges up Potomac Street. Feigenschuh was held as a prisoner of war until swapped in an 1864 prisoner exchange. (Robert Figenshu.)

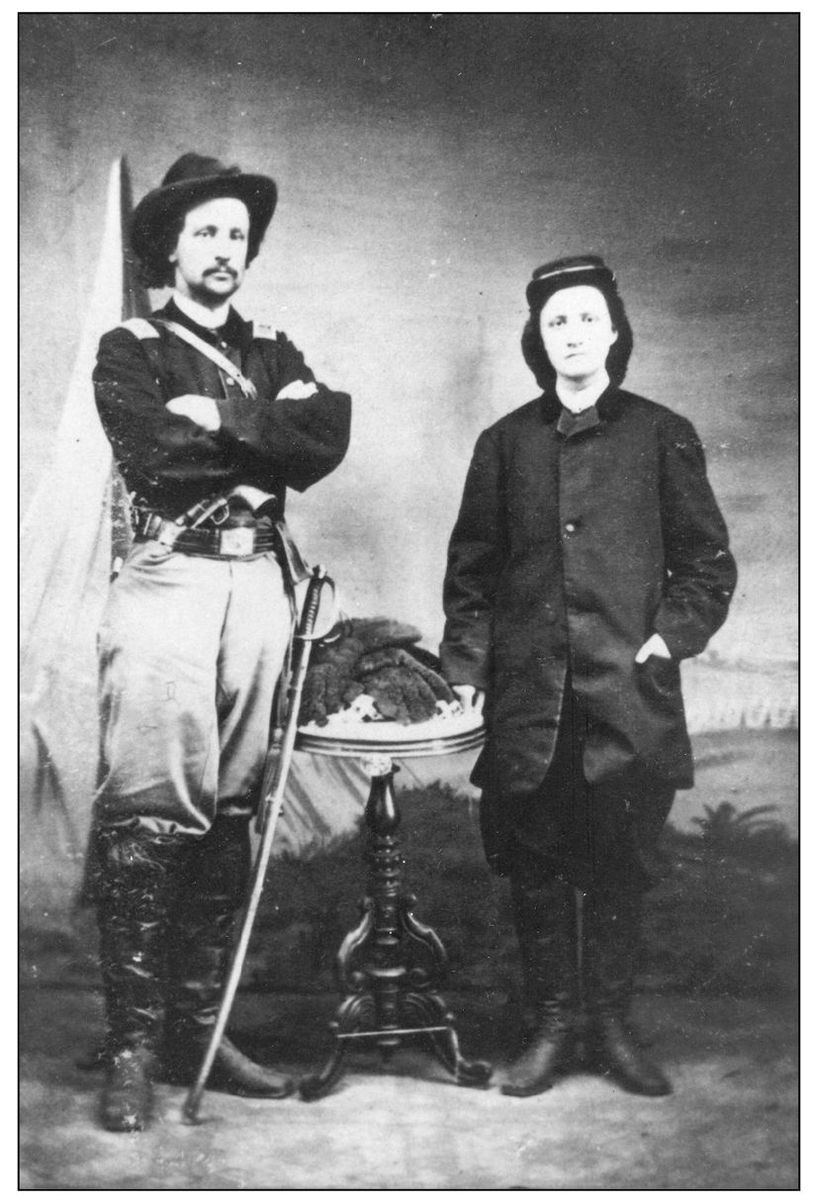

First Lt. Gilbert Steward (left) poses here in a very rare image with an unidentified woman dressed in a man’s uniform. Steward served in Company G, 1st Vermont Cavalry. He was wounded in the chest in the July 6 Battle of Hagerstown but recovered. (USAMHI.)

Pvt. Joseph E. Brewer served in Company B, 1st Vermont Cavalry. He was captured in the Battle of Hagerstown and was held at the Belle Isle prisoner-of-war camp, located on an island in the James River outside of Richmond. Private Brewer died of an unspecified illness at the prison camp on October 20, 1863, 14 weeks after his capture. (USAMHI.)

Brattleboro native Capt. Robert Schofield Jr. commanded Company F, 1st Vermont Cavalry. He was captured in the savage house-to-house fight in the streets and yards of Hagerstown in early July. Schofield mustered out as major of the regiment and lived in Wisconsin after the war. (USAMHI–Civil War Library and Museum, Philadelphia.)

Pvt. Dorence Atwater of the 2nd New York Cavalry was captured near Hagerstown on July 7 while carrying dispatches for General Kilpatrick. He was sent to Camp Sumter in Andersonville, Georgia, and assigned to the camp hospital. His job was to keep a record of all deaths that occurred. He kept the official Confederate record and maintained a second secret copy for himself. The official copy disappeared at war’s end; but using his own copy, Atwater teamed with Clara Barton and ensured that 13,000 deceased prisoners’ graves were individually marked. Due to his efforts, thousands of American soldiers do not lie in graves marked “unknown U.S. soldier.” (USAMHI–Massachusetts Commandery, MOLLUS Collection.)

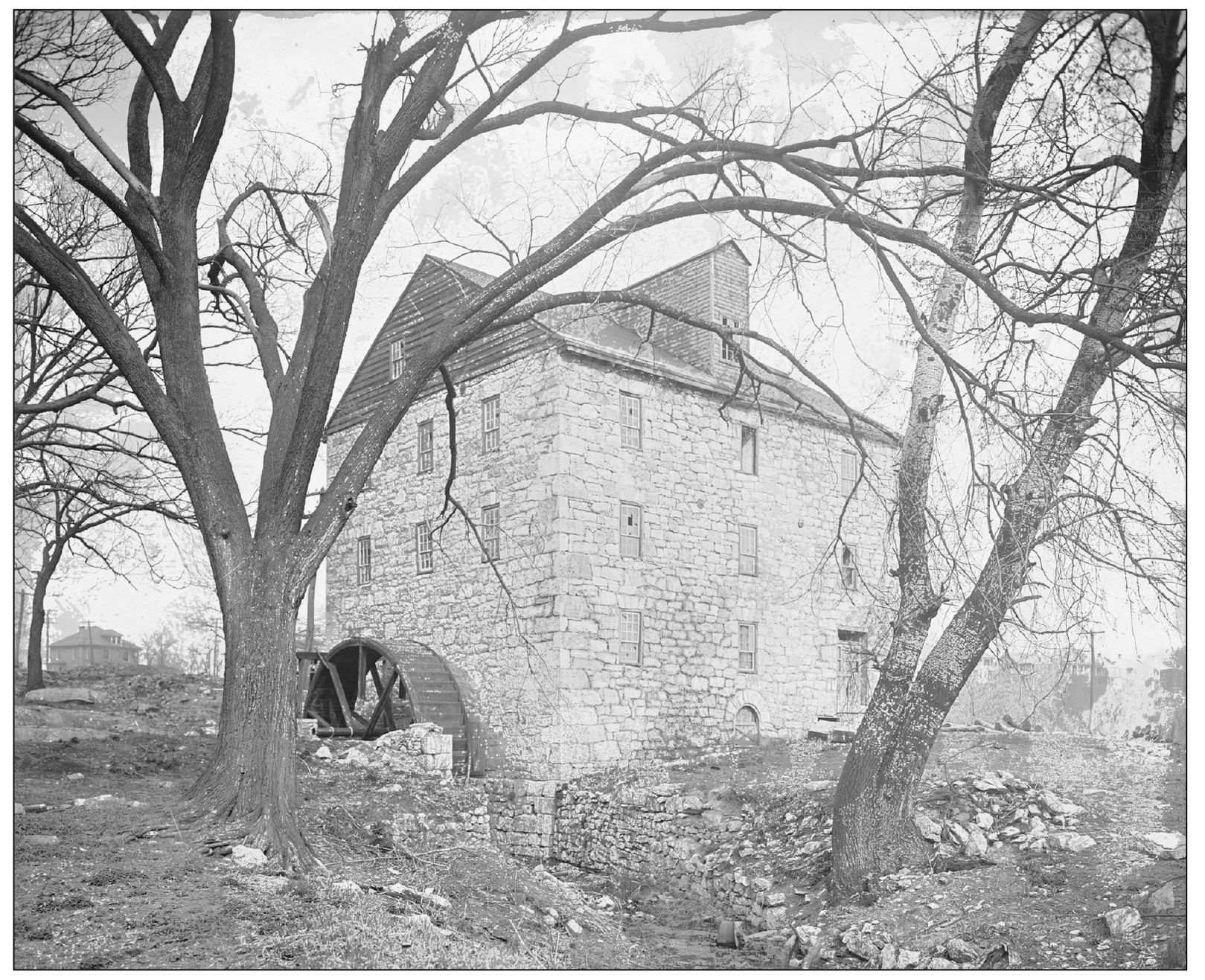

The Hager Mill on Mill Street is believed to be the scene of a July 6 encounter between troopers of the 11th Virginia Cavalry and a young girl with southern affection. She was wearing an apron in the red and white colors of rebel sympathy and was cheered by the soldiers as they passed. The girl gave the apron to Capt. Edward McDonald, whose command used it as a flag for the rest of the day. The “apron flag” became a noted sentimental artifact of the Southern cause, and an 1887 poem popularized the story. (Library of Congress.)

This replica of the historic apron flag was produced based on a photograph of the original in an old book. A Private Watkins of Romney, West Virginia, was mortally wounded near Jones’ Crossroads late on the July 6 carrying the apron flag in battle. The location of the original apron, if it still exists, is not known. (Author’s collection.)

Kee Mar College was again pressed into service by the Confederates as a hospital. Local doctors helped the Confederate medical staff tend to the hundreds of wounded arriving from Gettysburg and fresh Union and Confederate wounds inflicted in the battle in town. (WCHS.)

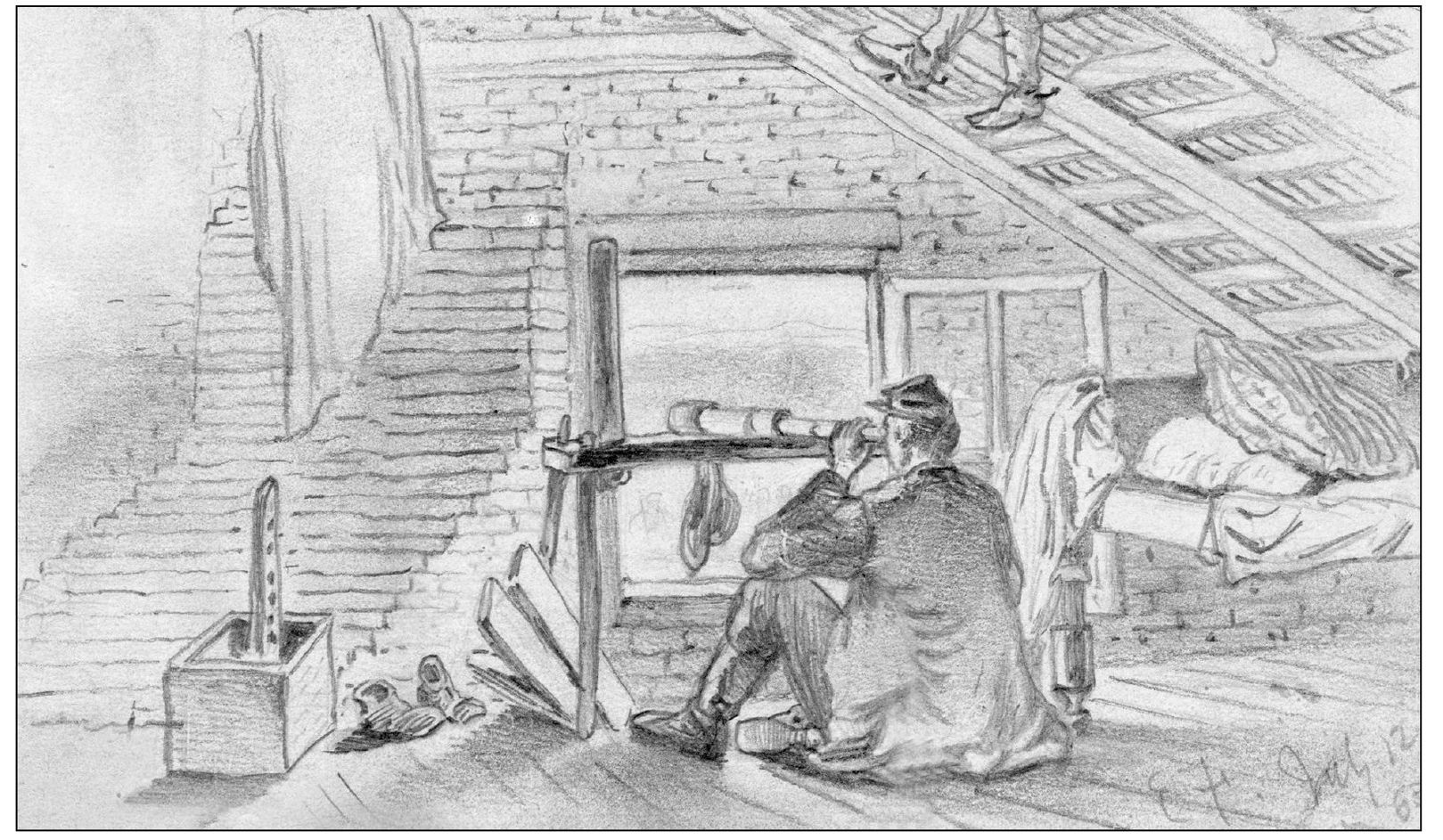

From July 6 until the Confederate withdrawal across the Potomac, the area between Hagerstown and Williamsport was a no-man’s-land between entrenched armies. Here newspaper artist Edwin Forbes depicts a Union observation post in the attic of a house in Hagerstown’s southern suburbs. The feet of a second observer can be seen near the top as he sits in a hatch or hole in the roof. (Library of Congress.)

When the Confederates evacuated Hagerstown, the wounded were entrusted to the care of such local doctors as John Absalom Wroe (pictured far right in the first row with his parents and siblings). Wroe must have felt many conflicting emotions dealing with the wounded Confederates. He was a native of the Commonwealth of Virginia. (Susan Howe.)

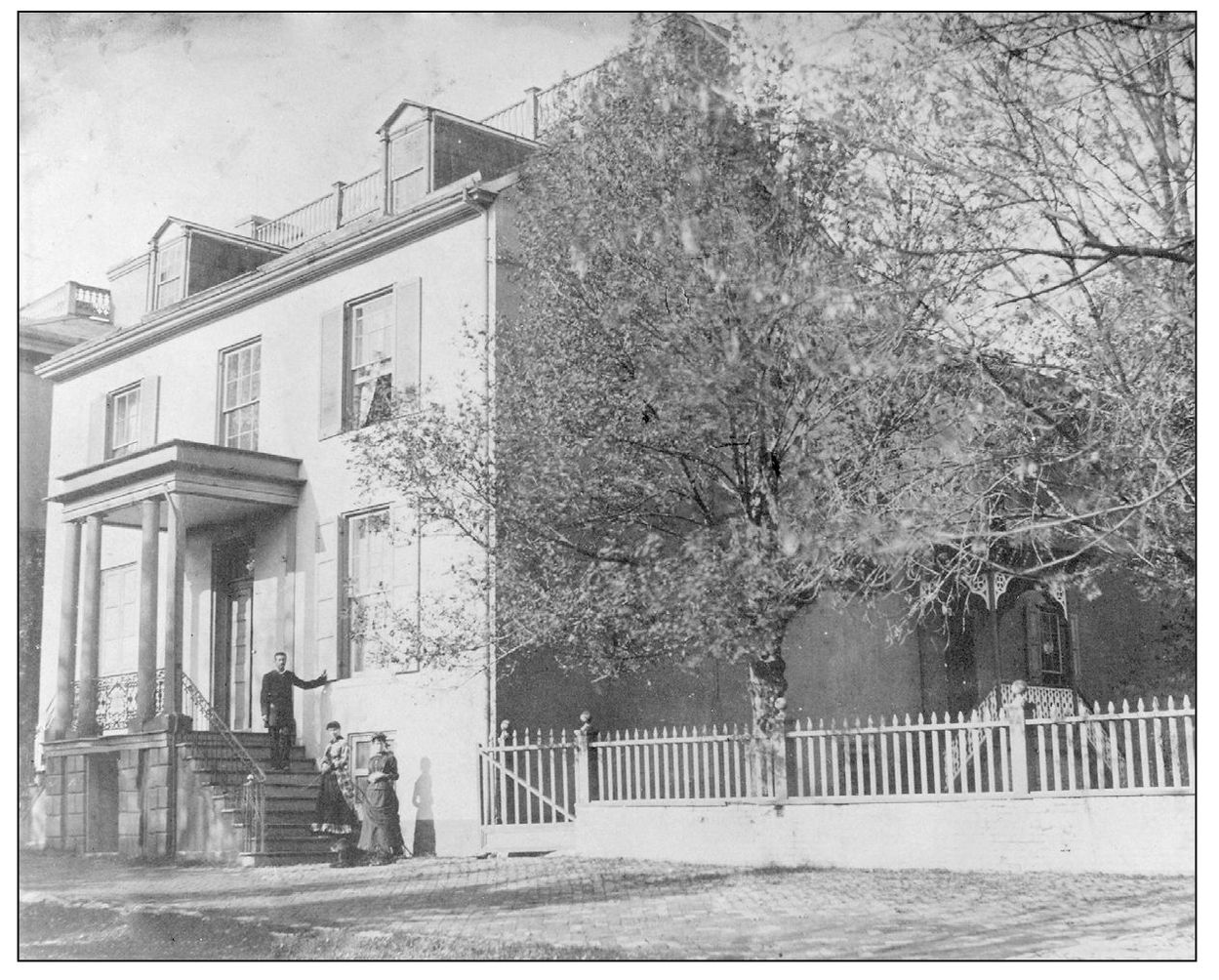

Dr. John A. Wroe lived on South Prospect Street. His residence, pictured here, stands today and is the home of the Hagerstown Women’s Club. Dr. Wroe hosted Gen. Robert E. Lee and his staff for dinner one evening during the retreat from Gettysburg.

(Susan Howe.)

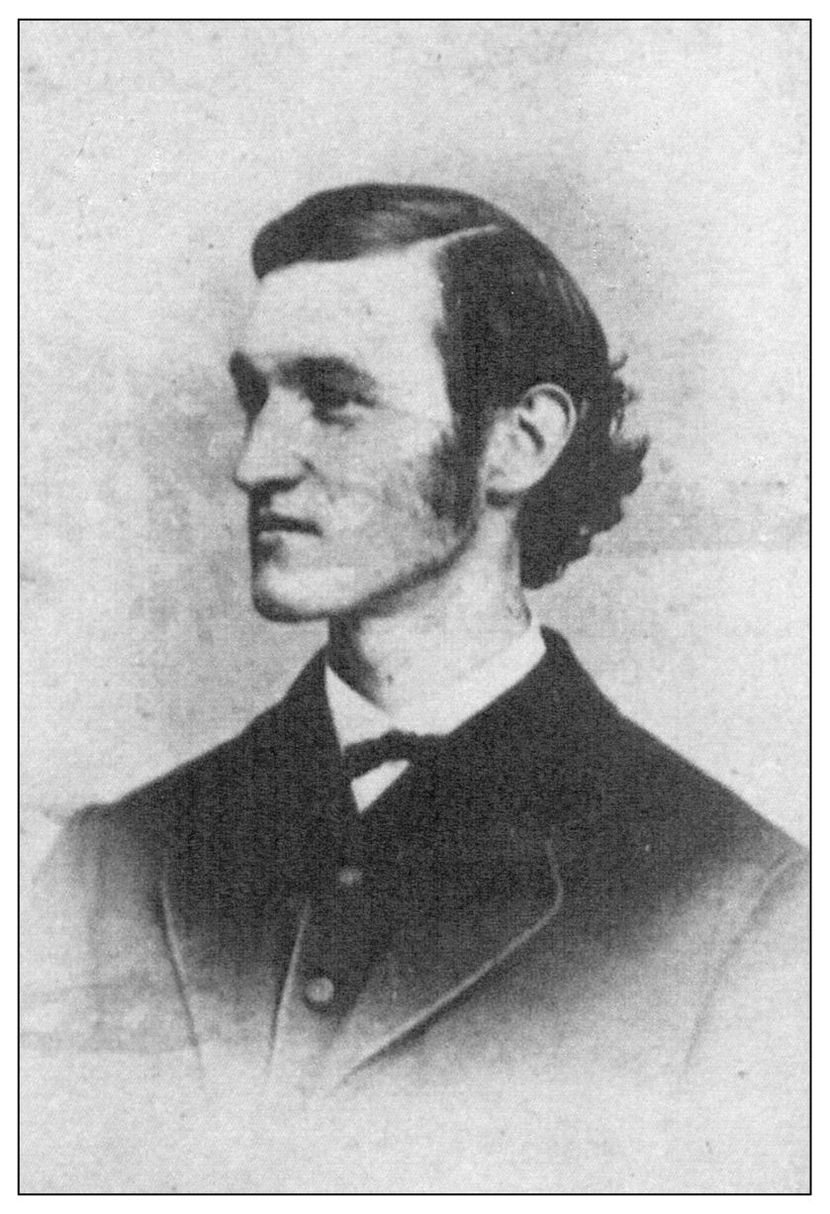

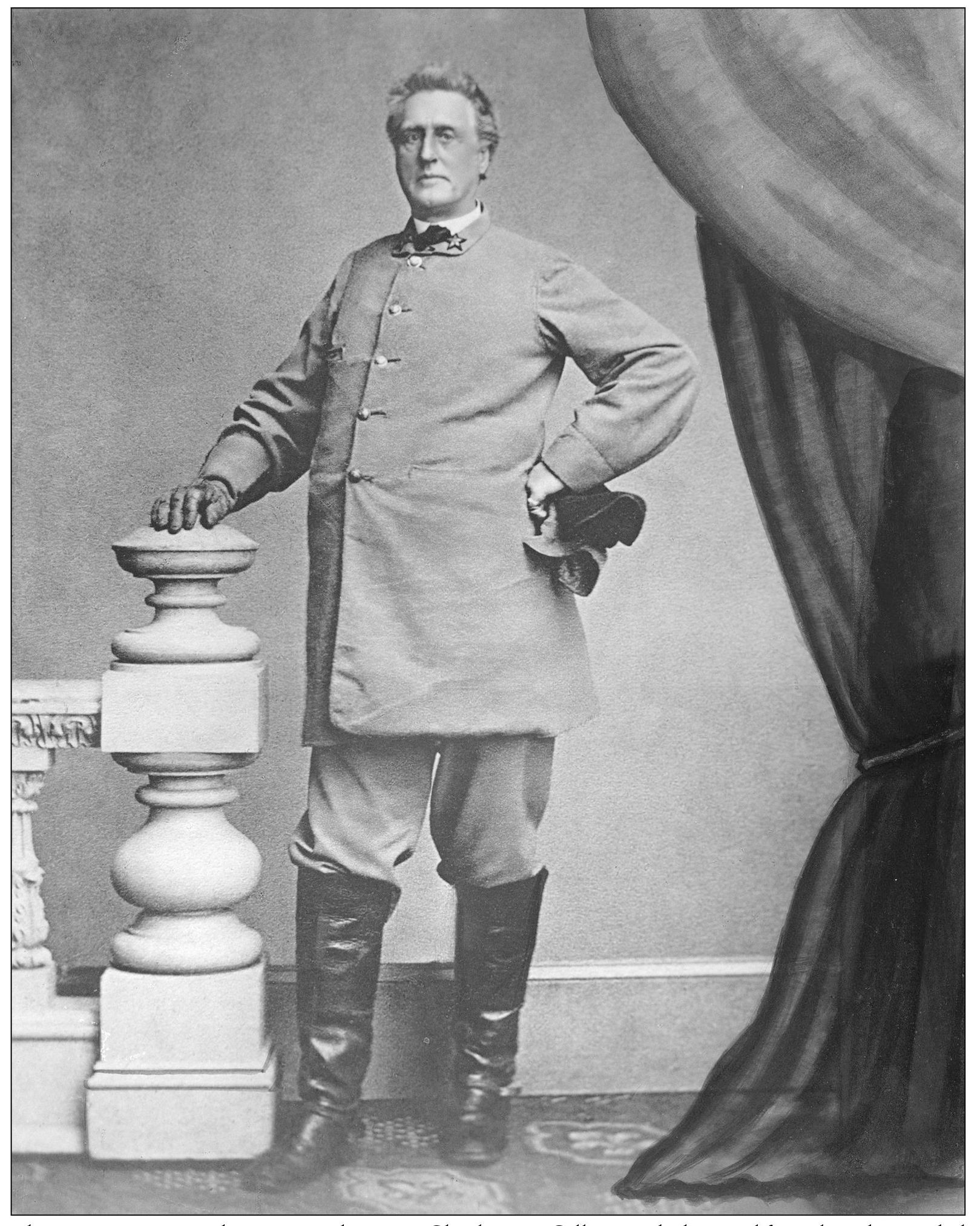

The unrepentant southern sympathizer Dr. Charles MacGill opened a hospital for sick and wounded rebels in Hagerstown. When Lee’s army retreated into Virginia, MacGill went with them and was commissioned a surgeon in the Confederate Medical Corps. He served in the hospitals around Richmond. His son, Charles G. W. MacGill, went to Gettysburg with Lee’s army. The younger MacGill also went south with his father and received a commission as assistant surgeon in the 2nd Virginia Infantry of the famed Stonewall Brigade. (Frederick D. Shroyer.)

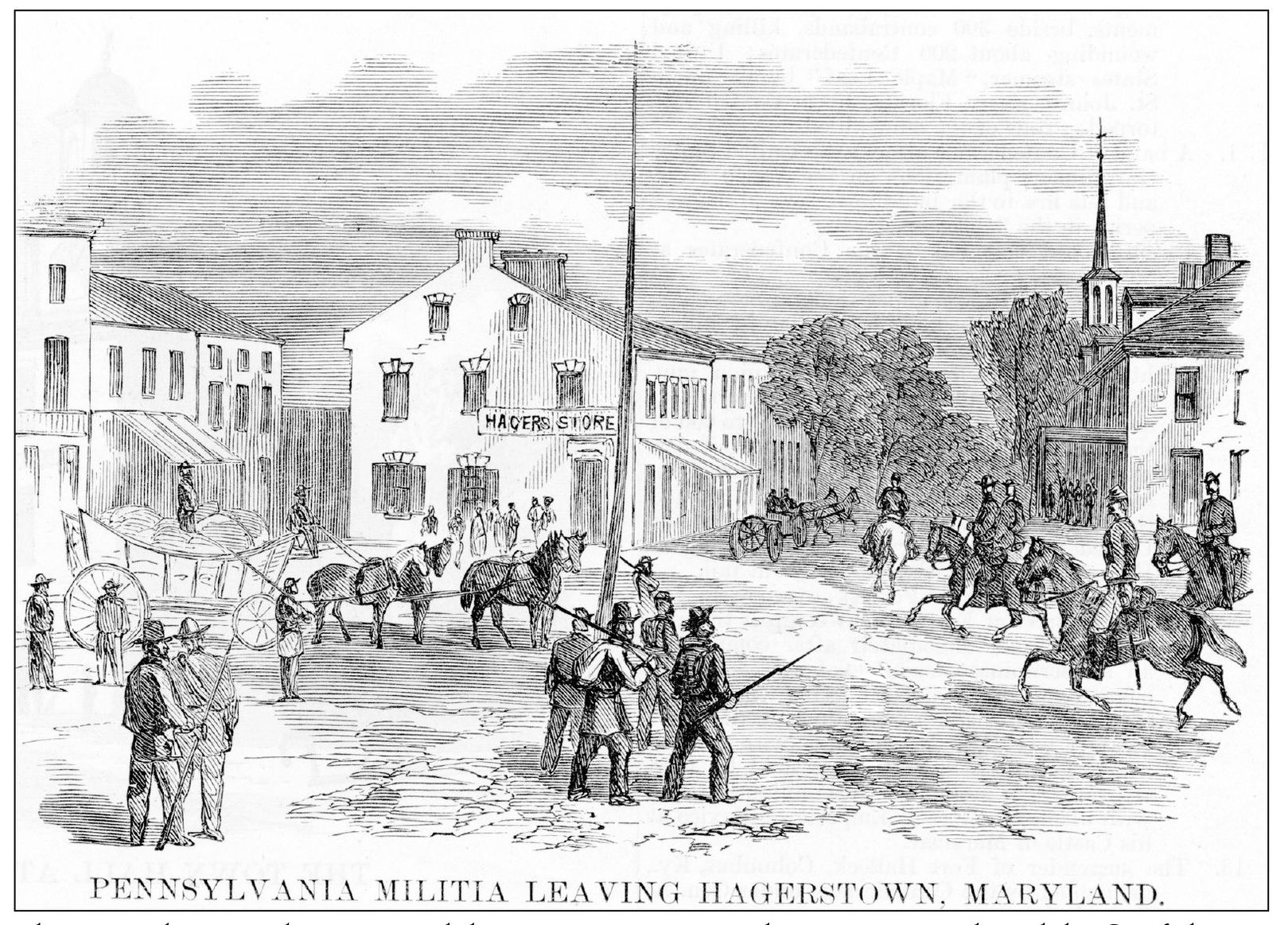

The Pennsylvania Militia occupied the Hagerstown area as the Union army chased the Confederates into Virginia. This image of South Potomac Street as seen from Public Square appeared in the New York Illustrated News in the weeks after the Battle of Hagerstown. (Ted Alexander.)

The buildings on the east side of the square in this c. 1890s image appear much as they did during the great street battle—although with some modifications. Today the Alexander House occupies the site of the buildings in the center and left of this image. (WCHS.)

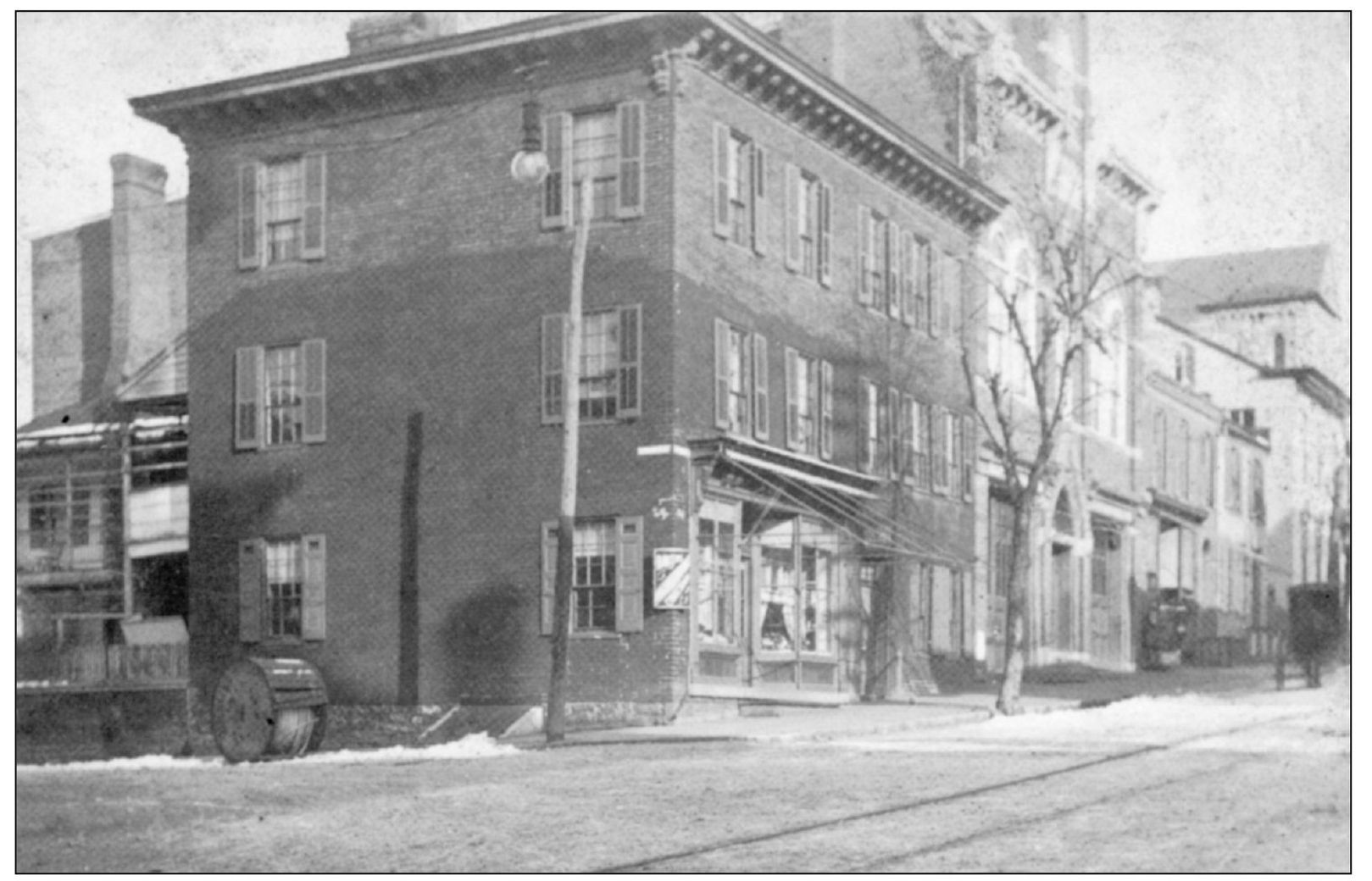

Time marches on for all things, and signs of change are everywhere. Here this 1890s photograph of the building on the northwest corner of Franklin and Potomac Streets shows that it was enlarged in the years after the war from a two-story building with a gable roof to a three-story flat-roofed structure. The rebuilt Junior Fire Company is at right. The area in the foreground is the site of Captain Dahlgren’s wounding during the battle, when he turned to the west upon discovering Confederates on West Franklin Street. (Maryland Cracker Barrel.)

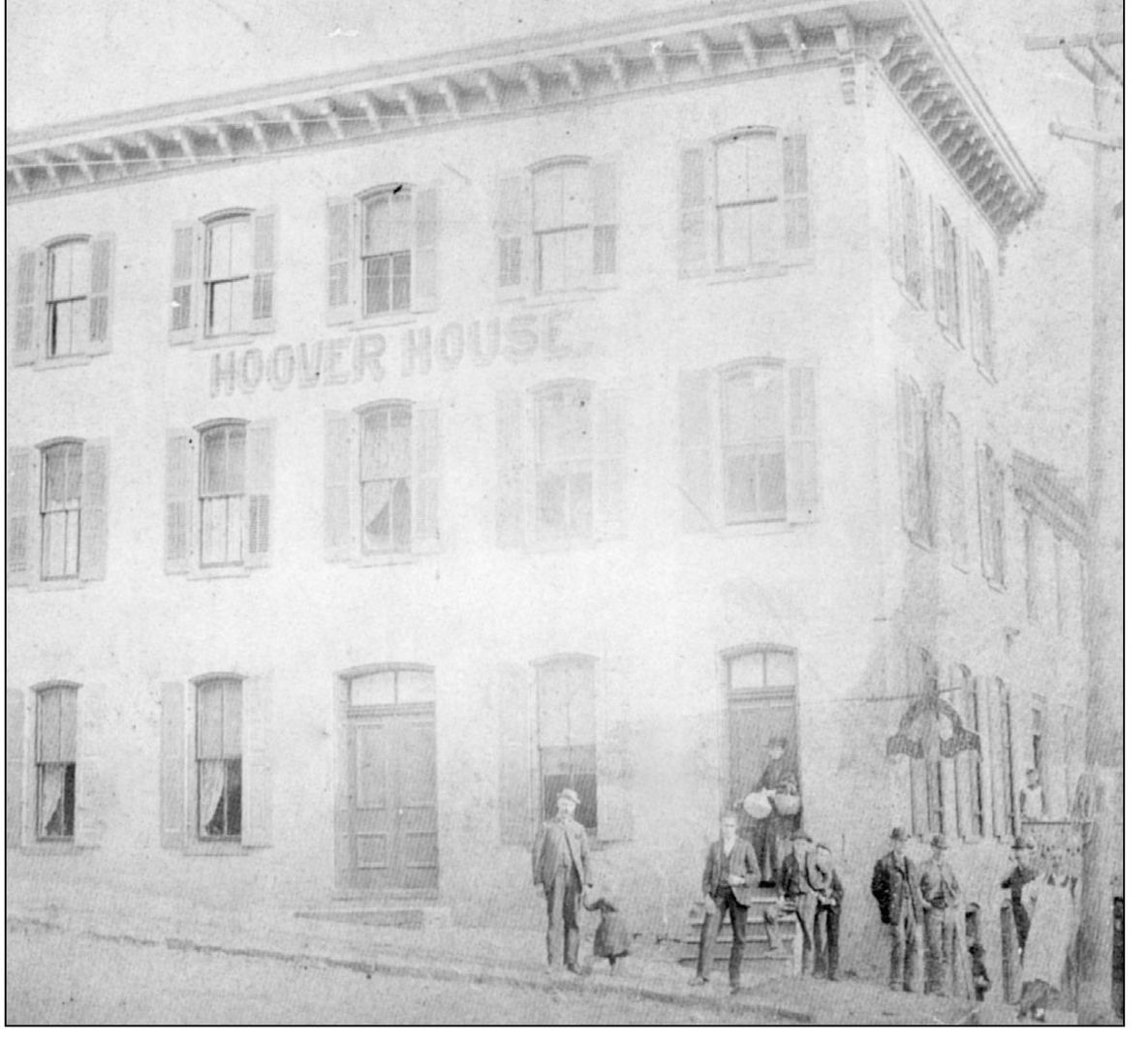

Another building that witnessed the Civil War is the Hoover House, now known as the Patterson Building. Located across Franklin Street from city hall, it was a popular hotel. On April 1, 1865, Joseph Hoover purchased the property from the estate of Agnes Finegan, but it is possible that he operated Hoover House as a tenant before he purchased it. (Maryland Cracker Barrel.)

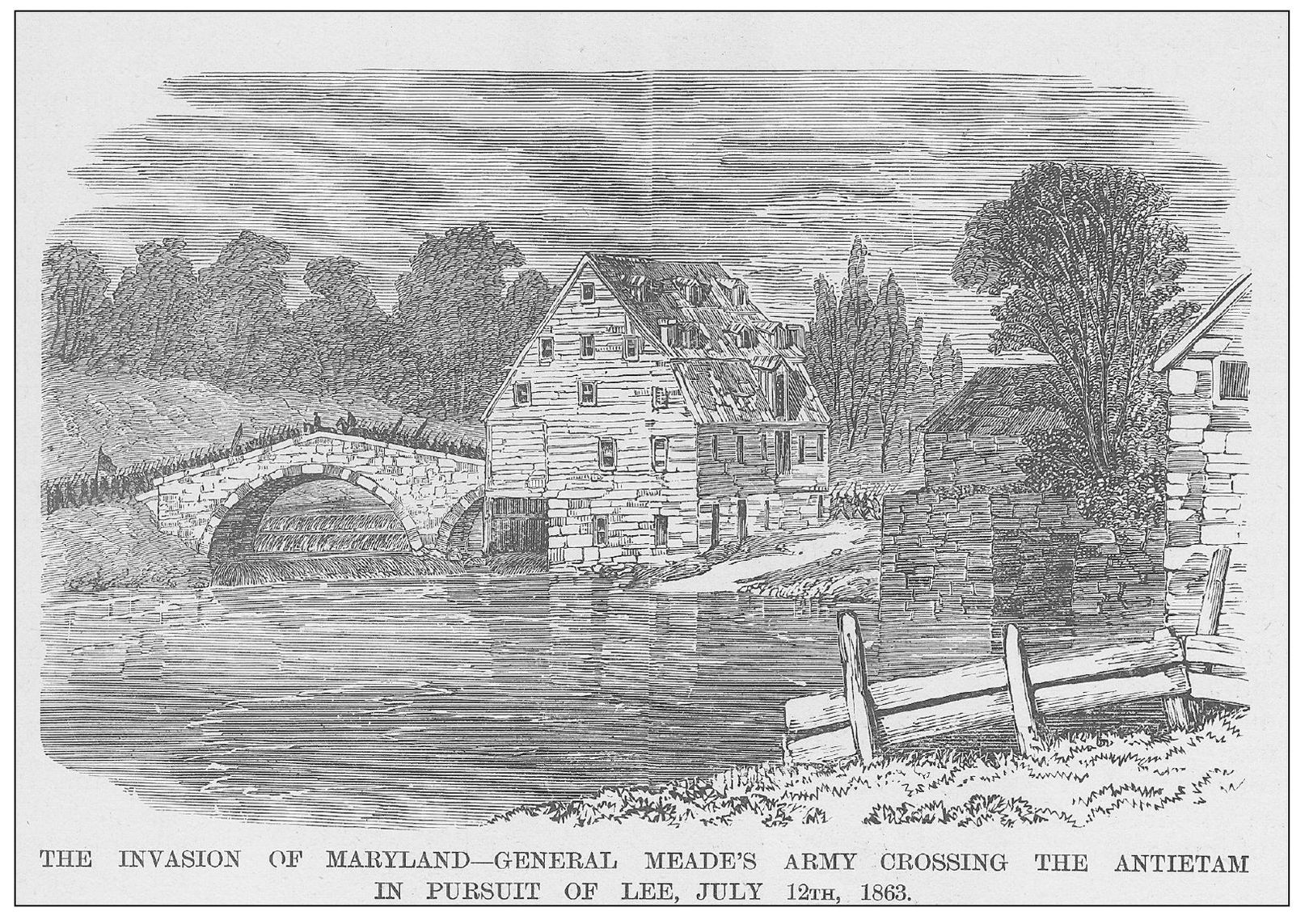

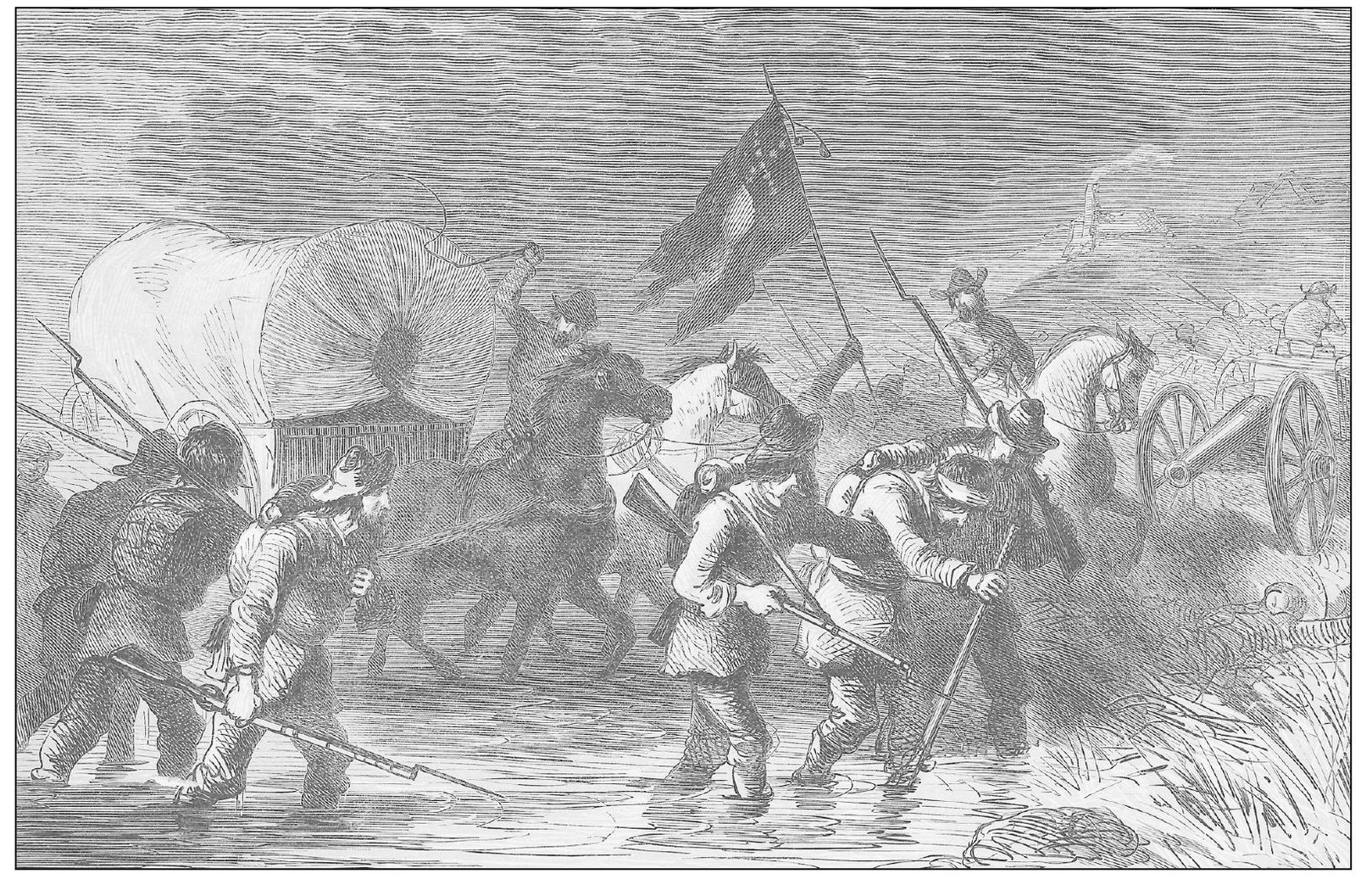

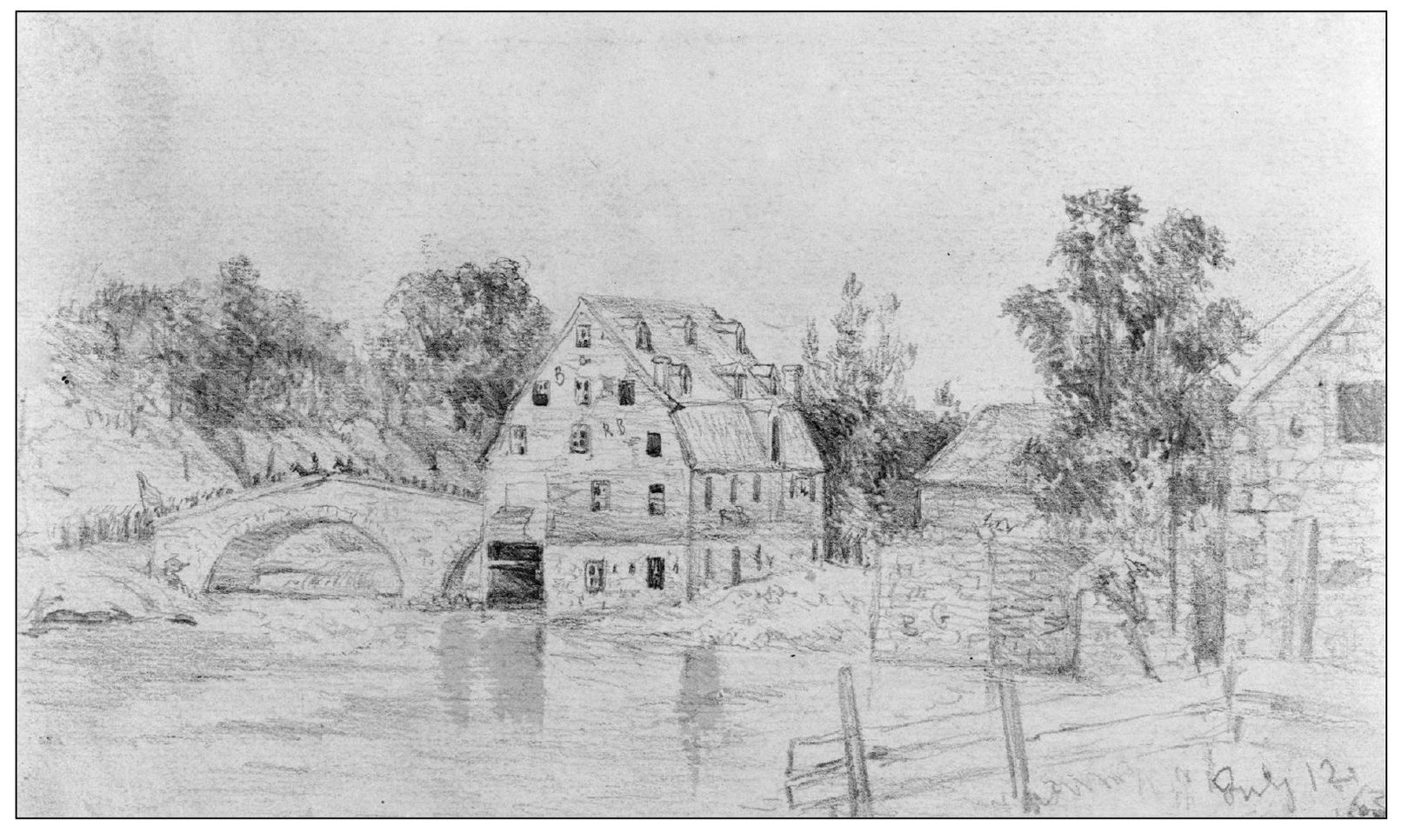

On July 12, Edwin Forbes, a correspondent/artist for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly, sketched Union troops crossing the Antietam “at Funkstown,” although it appears to be the Stull Mill at Mount Aetna Road’s crossing of Antietam Creek, with some artistic liberties. The sketch was sent by express to Leslie’s offices, where engravers transformed it into the woodcut seen below. The woodcut appeared in the August 1 issue of the magazine. (Above, Library of Congress; below, Tim Snyder.)