Four

RANSOM, REDEMPTION, PEACE, AND TRAGEDY 1864–1865

As warring armies fought within miles and while troops regularly marched through and occupied Hagerstown, life went on for the local citizenry. Here several Hagerstown men lounge outside of Ullrich’s Tobacco Store in 1864. Ullrich’s was located on the south side of West Washington Street between today’s Washington County Historical Society and the Discovery Station. Instead of the usual cigar store Indian, an African caricature is used in front of the shop. (WCHS.)

This photograph from around 1900 depicts a row of houses on the south side of East North Avenue, just east of North Potomac Street. The steeple of St. Paul’s (now Otterbein United Methodist) Church on East Franklin Street is in the right background. Many of Hagerstown’s Civil War–era homes have disappeared, including these, but they represent the working-class housing stock that existed in Hagerstown during the Civil War. (WCHS.)

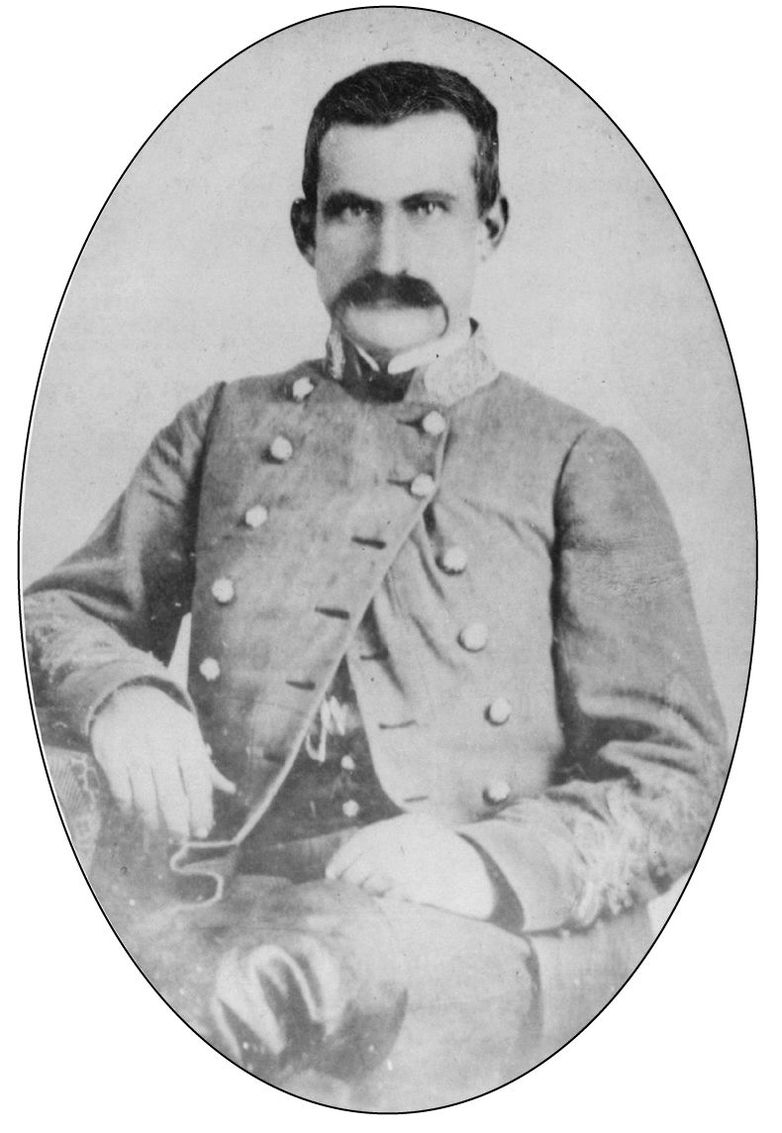

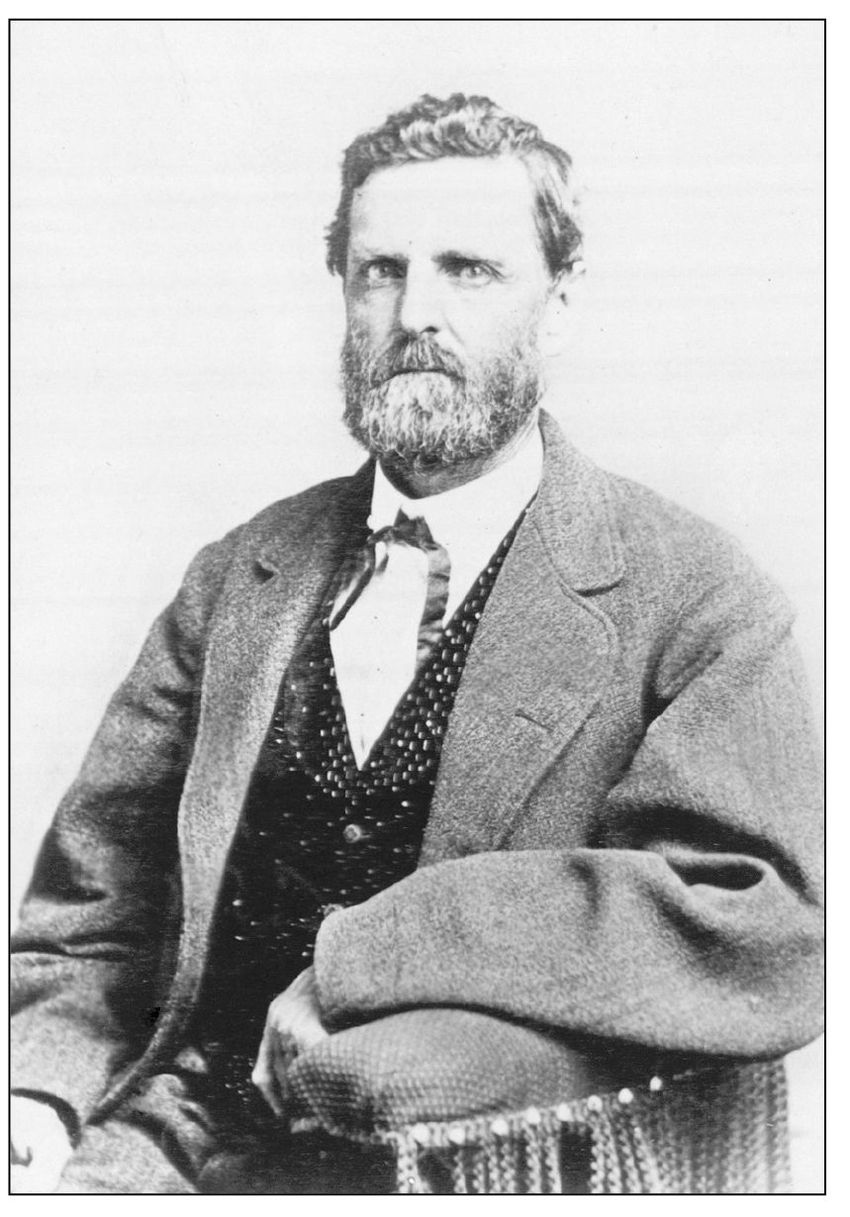

On July 6, 1864, exactly one year after the Battle of Hagerstown, a 1,500-man cavalry brigade under Brig. Gen. John McCausland (left) came to Hagerstown. They were part of a small army under Gen. Jubal Early that had invaded Maryland to draw Union forces away from Lee’s beleaguered army outside of Richmond. McCausland came with orders from Early to demand a ransom from the citizens to prevent the burning of the city in retaliation for scorched-earth tactics employed by Generals Hunter and Sheridan in the Shenandoah Valley. (West Virginia State Archives.)

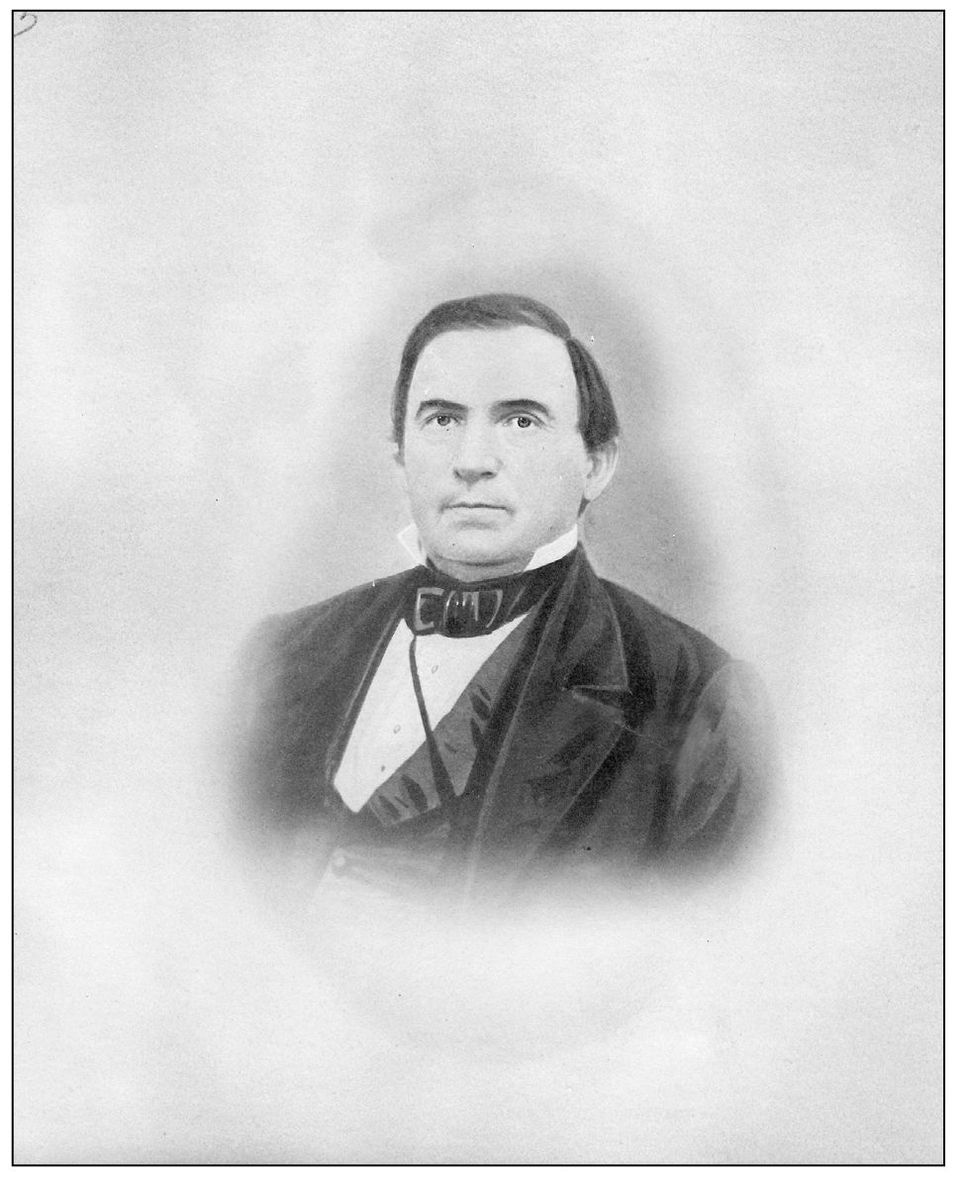

McCausland established his headquarters in the town hall and met with city treasurer Matthew Barber (right) and the teller of the Hagerstown Bank, John Kausler (below). McCausland presented a written demand for $20,000 and 1,500 complete sets of men’s clothing, with a deadline of three hours to produce all the funds and materials in the written demand. Barber and Kausler argued with the general that the expectations were impossible to meet on such short notice, but there was no negotiation. (Author’s collection.)

John Kausler was employed in various positions by the Hagerstown Bank from the 1850s until the 1890s—first as teller, then bookkeeper, and finally as cashier. This photograph was taken late in his life, years after the war. (Author’s collection.)

McCausland’s demand was photographed by Bascom Phreaner in 1869. McCausland exacted $20,000 from the city plus 1,500 complete sets of clothing, a number corresponding with the number of men in his command. (Author’s collection.)

Barber and Kausler turned to James Dixon Roman, president of the Hagerstown Bank and a former congressman during the Mexican War. Hobbled by a spinal illness, he could not walk to town hall from his home on West Washington Street. McCausland met him at the county courthouse. A stern discussion commenced in which Roman made it clear that they would find the funds but that it was entirely impossible for a town of 4,500 to secure 1,500 complete sets of clothing in three hours. (City of Hagerstown.)

Located west of Public Square, the Hagerstown Bank (left) was the heart of the city’s financial industry. Roman arranged for his bank and two others to provide the cash ransom. The building was demolished in 1937 for a Montgomery Ward department store, which is now an office building for the Washington County government. The bank’s successor in 2010 is the Hagerstown Trust Division of The Columbia Bank. The Updegraff buildings to the right still stand. (Maryland Cracker Barrel.)

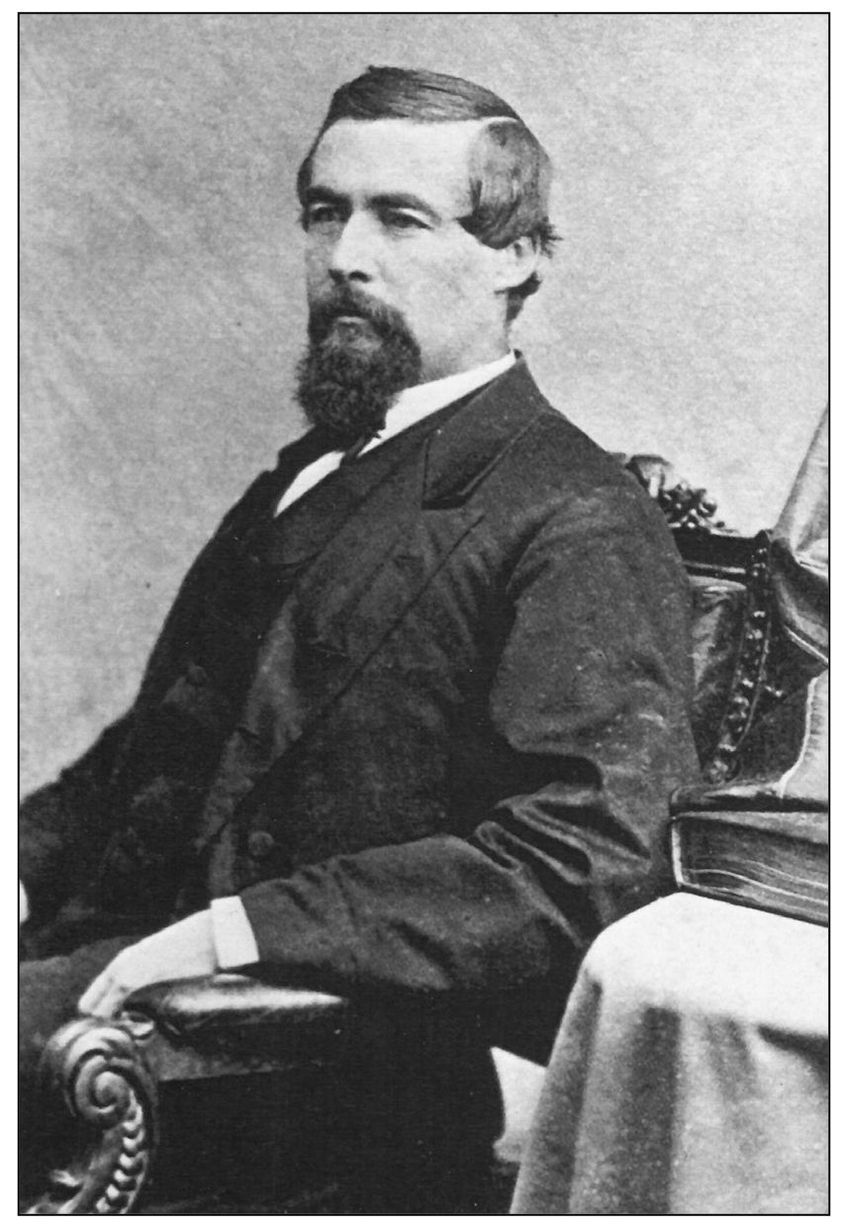

Former congressman and Hagerstown Bank officer William T. Hamilton met McCausland and Roman at the courthouse. He strongly argued the lack of reason in requiring 1,500 sets of clothing in three hours from a town the size of Hagerstown. McCausland relented, demanding all the clothing that could be rounded up in three hours, with the understanding that Roman, Hamilton, and Kausler would keep the arrangement a secret from the citizens, so as to not encourage holding out or a slow response. As far as the citizenry knew, they had to produce 1,500 sets of clothing to save Hagerstown from the torch. (U.S. Senate Historical Office.)

Clerk of the circuit court Isaac Nesbitt was also engaged in the heated debate at the courthouse. After a settlement had been reached, McCausland, being in a hurry to rejoin Early’s army, required Nesbitt to give his personal bond assuring that he would arrange for the destruction of the government’s stores of war material at the Franklin Railroad’s Walnut Street depot. His son, Alexander, was a captain in the 1st Maryland Cavalry (Union) and died in 1863. (WCHS.)

The grind of war resulted in the Confederates’ conduct deteriorating from the largely respectful presence they exhibited during the two previous invasions. In the July 30, 1864, issue of Harper’s Weekly, rebel quartermasters are shown commandeering the contents of Andrew Hager’s Mill on Mill Street. (Tim Snyder.)

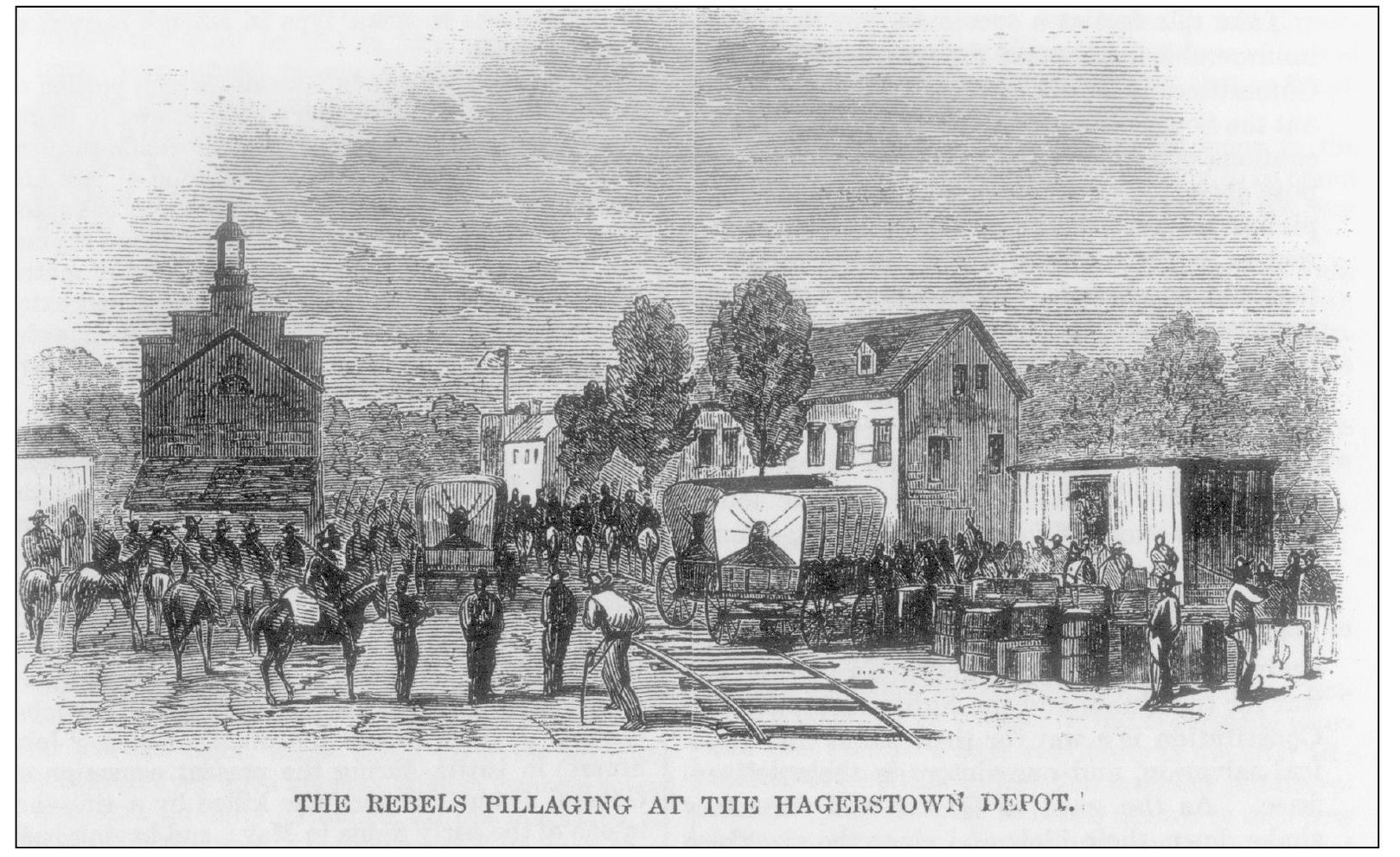

The Confederates also took as much from the army depot on Walnut Street as they could before it was burned. This image, looking south on Walnut from Franklin Street towards Washington, shows the back of St. Mary’s Church on the left. This image also appeared in the July 30 issue of Harper’s Weekly. (Tim Snyder.)

Those stores that were not cleaned out to meet McCausland’s demand were treated roughly by Confederate soldiers, who paid for their “purchases” in Confederate money, which had no value in the North. Many small businesses were affected by Early’s Raid. This c. 1880 photograph shows the common appearance of storefronts in Hagerstown during the war. (WCHS.)

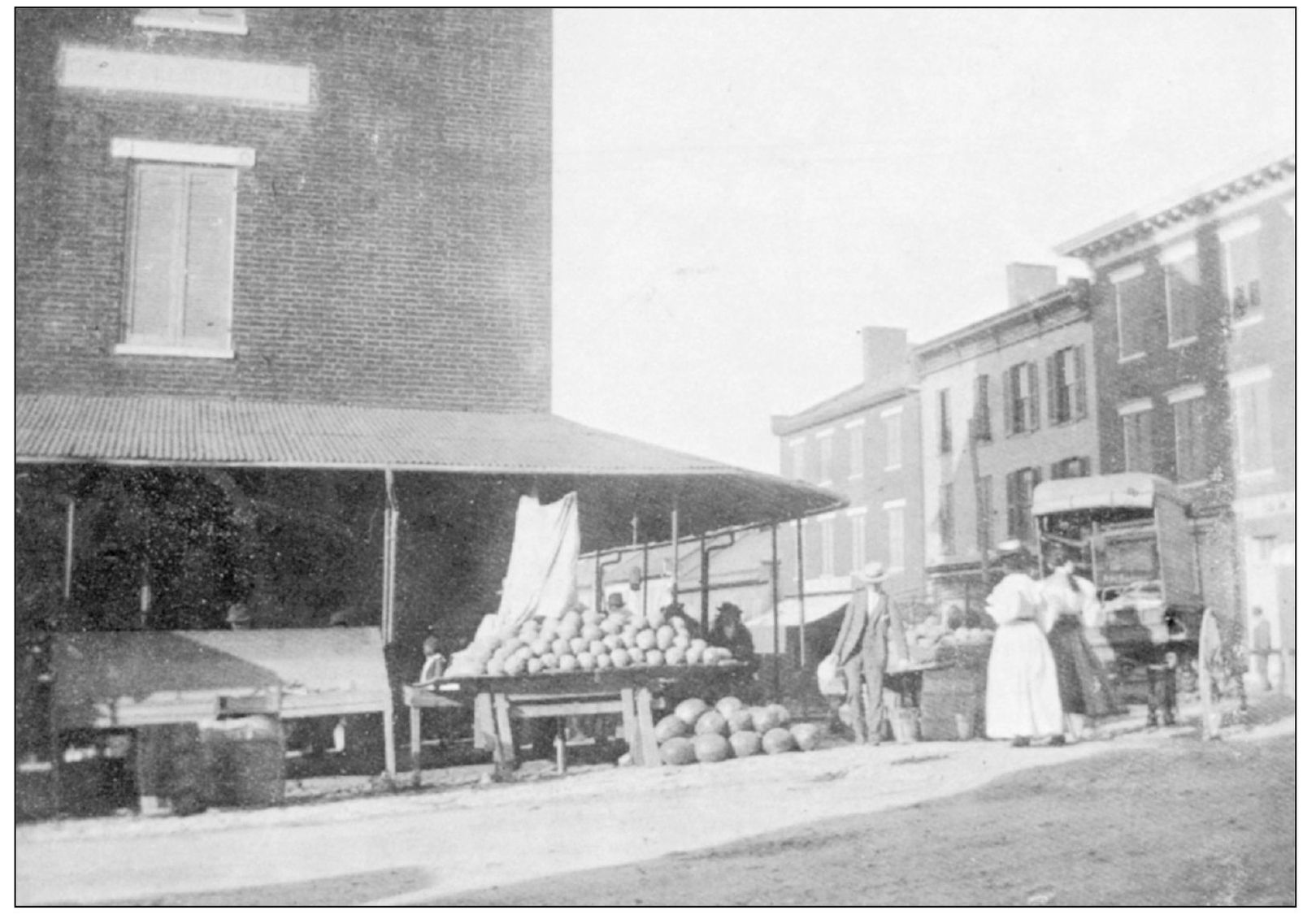

Although the city market canopy did not exist during the Civil War, this c. 1890s photograph of the intersection of Franklin and North Potomac Streets shows it much as it was when McCausland made the town hall his headquarters in July 1864. (Maryland Cracker Barrel.)

To confirm compliance and secure the town from further demands, General McCausland provided the city with a receipt for the ransom. Included in that acknowledgment was an inventory of the clothing that was collected in the allotted three-hour period. (Author’s collection.)

Col. Henry A. Cole of Frederick (left) commanded a regiment of Maryland cavalry. On July 29, his troops battled a brigade of Confederate cavalry for three hours until they were compelled to retreat toward Greencastle. The force he opposed was commanded by Brig. Gen. John Crawford Vaughn of Tennessee. (USAMHI.)

After pushing Colonel Cole’s men out of the city, Vaughn’s forces entered the Franklin Railroad yards on the west side of the town and destroyed as much of the railroad equipment and stockpiled supplies as they could in the limited amount of time they had to work. Vaughn’s force circled through the area again on August 5 and engaged in what would become the last Confederate occupation of Hagerstown. (USAMHI–Massachusetts Commandery, MOLLUS Collection.)

The topographical engineers (mapmakers) of both the Union and Confederate armies left fairly detailed records of the actions in local areas. General Meade’s engineers produced maps showing the trenches created between Hagerstown and Williamsport in 1863 that can be compared against modern maps to identify approximate locations of the positions both armies held. Here Jedediah Hotchkiss, the mapmaker attached to Early’s army, filed a report containing this map accurately showing Hagerstown’s street layout at that time and the positions of Union and Confederate cavalry involved in a skirmish on the edge of town in late July. (Author’s collection.)

South Prospect Street was developed in the 1830s and 1840s. The house in the right background is located where North Prospect Street lies today. Beyond the fence in the center is the Rochester House. Both homes on the left in this c. 1870s photograph still stand. (WCHS.)

This postwar image depicts the 100 block of West Washington Street as it would have appeared during the Civil War. The building that now houses the Washington County Historical Society is on the far left. The photograph was taken in front of the home of Dr. Augustine Mason, who commanded the Confederate military hospitals in Richmond from 1863 until the end of the war. (WCHS.)

J. H. Beachley’s Dry Goods Store was located on the northeast corner of Public Square. This photograph appears to date to around 1870. The street to the right is East Washington Street. This streetscape, with the storefront, corniced buildings, and structures with sloped roofs and dormers is very characteristic of the city center area of Hagerstown during the mid-19th century. Beachley’s Dry Goods Store survives to this day as the Beachley Furniture Company. (Maryland Cracker Barrel.)

In early April 1865, word came from the hamlet of Appomattox Courthouse in Virginia that the Army of Northern Virginia had finally been compelled to surrender to Union forces. When this news reached Hagerstown, civic celebrations were held by the pro-Union majority in the community, while those who supported the vanquished Confederacy quietly mourned the loss. Less than a week later, joy turned to shock and sorrow on the parts of almost all residents, regardless of their sympathies in the war, when word was received that President Lincoln had been assassinated. Businesses closed, public buildings were draped in black, and churches conducted memorial services. This handbill, photographed in an exhibit at the Washington County Museum of Fine Arts, was published by the Herald and Torchlight to spread information as quickly as possible about the calamity that had befallen the nation. (WMR-WCFL.)