The sight of us setting off into the dark brought Mrs Henderson running. Together, we soon found Queenie’s house, which stood halfway down the main street. Just as Gloria predicted, you could see the lighthouse properly from here – or as properly as was possible in the dark.

‘This is it,’ Mrs Henderson shouted over the wind. ‘The post office.’

Yet the post office part was only one small bay window with the blinds pulled down. The rest of the house towered above us, important-looking with wide steps leading up to a huge front door. My jaw dropped in amazement at the size of it.

‘Blimey!’ Cliff gasped. ‘It’s massive!’

Shivering with cold and tiredness and the last glimmers of excitement, I tucked my arm through his. ‘Isn’t it marvellous?’ I couldn’t wait to see inside.

Yet after three hearty raps on the front door Queenie still didn’t appear.

‘She’ll be down in the cellar, unable to hear us,’ Mrs Henderson muttered in annoyance. ‘Knock on the glass, Olive, will you?’ and she pointed to the left of the steps where, almost hidden by ivy and blackout curtains, was a cellar window.

I did as she asked. Finally, as we heard footsteps approaching from the other side of the door, a sudden bout of shyness came over me. The person I was about to meet was Sukie’s penpal. She’d be wonderful, I was certain. I just hoped she didn’t mind having us foisted on her, a pair of windswept, homesick kids.

The door inched open. From behind it peered a small, plain-looking woman who at first glance could’ve been fifteen or fifty. She was wearing an enormous green sweater that reached her knees. Assuming she was the housekeeper, I stared past her into the hallway.

‘Your evacuees are here, Queenie,’ Mrs Henderson said rather pointedly.

‘My –?’ The woman clapped a hand over her mouth. ‘Oh! Is it that time already?’

I put down my suitcase in surprise. So this was Queenie? I could see now she wasn’t that old. She wore glasses and had freckles and reddish, poker-straight hair. I supposed I was expecting someone fashionable like Sukie, and she wasn’t.

Clearing my throat, I stammered, ‘We’re … ummm … We live next door to Gloria in London. She … umm … arranged for us to come and stay.’

Queenie eyed us coolly. Her glasses were so thick it was like being stared at through a fish tank. ‘You’re rather weedy-looking. I was expecting someone stronger.’

I blinked, taken aback. Sukie always said I was slender, which sounded nicer even if it wasn’t true.

Queenie brightened. ‘Can you run? Who’s the faster, you or your brother?’

‘Umm …’ I stuttered. ‘I’m not sure.’

‘I was the fastest in my class at school,’ Cliff chipped in.

‘And even weedier than your sister, by the looks of you,’ Queenie remarked.

Cliff stared at her, wide-eyed and open-mouthed. It was almost funny, except it was taking all my concentration now not to burst into tears.

Mrs Henderson sighed. ‘For heaven’s sake, Queenie, let the poor devils at least get inside. They’re exhausted.’

‘I’m checking their credentials,’ Queenie replied sharply. ‘I need workers, Mrs H. You know how busy it’s been here since I lost the Jenson boys.’

‘Who’re the Jenson boys?’ Cliff asked before I could.

Queenie ignored him. It was Mrs Henderson who explained: ‘A couple of local lads who worked for Queenie in the shop, doing deliveries. They’ve been called up for the army.’

‘I’ll be expecting you two to pull your weight,’ Queenie added. ‘Call it the war effort if you like, but be warned: I’ve no time for idlers.’

My hopes of exploring the beach tomorrow faded, though I was willing to do my bit – more than willing – especially if it meant getting back at Mr Hitler. I’d lost my dad to this stupid war, which surely meant I had the right credentials. I’d have explained this too, had Mrs Henderson not given me a little shove in the direction of the door.

‘In you go,’ she said.

We stumbled inside. I was glad to be out of the wind at last. But as the door closed, I realised Mrs Henderson was no longer with us and I suddenly didn’t feel so brave about being on our own.

‘She’s gone to milk her goats,’ I reminded Cliff, who managed a feeble smile. Reaching for his hand, I put the last of Gloria’s toffees in his palm.

Queenie took us into a hallway. There weren’t coats or umbrellas or gas masks hung on hooks like at home. This hall smelled fusty as a church and echoed like one too, as the floor was paved with flagstones. The only light came from the candle Queenie held. It wasn’t what I expected: none of this was.

‘Follow me,’ she said, leading us deeper into the house.

From the hall, we went up a staircase lugging our suitcases, satchels and gas-mask boxes. All day I’d built up an idea of Queenie in my head: the reality was … different … and, I had to admit, horribly disappointing. She hadn’t remembered we were coming. She hadn’t even mentioned Sukie, and she was supposed to be her friend. As for supper, I was beginning to give up hope.

At the top of the stairs, we trudged along a landing where the floor tilted and creaked, and where the dark grew ever darker.

‘She’s not on the electric, is she?’ Cliff hissed in my ear.

‘Doesn’t look like it,’ I agreed, wondering what else Gloria hadn’t told us about her sister.

Finally, we stopped in front of another staircase, this one so steep it was almost vertical.

‘I’ve put you in the attic,’ Queenie said.

Beside me, I sensed Cliff stiffening up. He hated heights. And those stairs – slippery, painted, uncarpeted wood – looked capable of breaking necks.

‘You’ll want to unpack, I expect. Don’t let me keep you,’ muttered Queenie, though once she’d given me what was left of her candle it was obviously us keeping her.

Cliff and I shared a bewildered look.

‘Um … I don’t mean to be rude,’ I said. ‘But are we having supper?’

‘Are you expecting me to cook?’ She made it sound like I’d asked for a trip to the moon.

‘We haven’t eaten since the train,’ Cliff replied, swallowing his toffee in one gulp.

Queenie said nothing.

I knew when we were beaten. ‘I’m done in, Cliff. Let’s just go to bed.’

*

The attic stairs weren’t as bad as all that. I made sure of it by insisting Cliff go first, so if he slipped I’d at least try to catch him. At the top were our bedrooms, two huge rooms that stretched the whole length of the house. There wasn’t much furniture in mine – a bed, a chest of drawers, a bedside table, a rag rug on the floor. It reminded me of a horrid boarding school, the sort that naughty children get sent to in stories. Despite putting away my skirts and sweaters and arranging my hairbrush and clips on the bedside table, it still didn’t feel homely. My books looked lost on the huge, wide windowsill. I didn’t even unpack Dad’s seashell.

Cliff’s room was just as vast and cold, with a bed that sagged like a hammock. This I found out as I perched on it to wish him goodnight.

‘It won’t be for ever,’ I promised. ‘I’m sure we’ll have a decent breakfast in the morning.’

Luckily, Cliff was already falling asleep. ‘It’s not that bad,’ he mumbled into the pillow. ‘Though I was really hoping she’d have a dog.’

It was Queenie’s chilly welcome that sat uneasily with me. Odd that our sister – popular, fun, pretty as a pin-up – would be friends with someone who wore old droopy sweaters and didn’t actually seem to like people very much. Other than being a similar sort of age, I couldn’t think what they had in common.

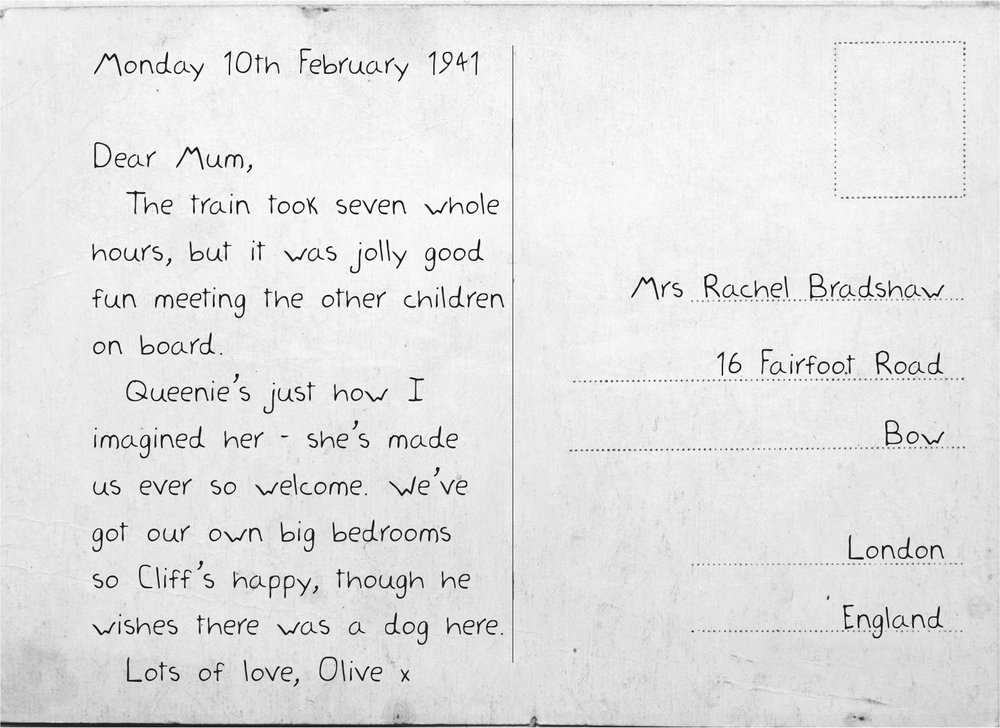

Back in my room, I got into bed. The sheets, the pillowcases – everything felt damp with cold. Heaping all the blankets I could find over me, I climbed back under the covers and decided to write a postcard home to Mum; we’d all been given a pack of blank ones earlier by Mr Barrowman.

‘Keep your messages cheerful,’ he’d warned us. ‘No homesick blubbing. No moaning about your hosts. Your parents have more important things to worry about than you lot.’

Blowing on my almost-numb fingers, I got to work.

The candle Queenie’d given me soon burned low. What helped was the lighthouse beam as it swept through the attic: count to six and it was dark, count another six and it went bright again, edging the blackout curtains with gold.

It didn’t bring any heat, though, and once I’d done the postcard, I got out of bed and put on Mum’s coat over my nightdress. It smelled faintly of Sukie still and something smoky and bitter. Giving it a big sniff, I breathed my sister in, though the smoke smell was stronger and I didn’t like the way it reminded me of the air raid, filling my head with shadows.

Enough, I told myself. Go to sleep.

I couldn’t get comfortable. The sandwich wrappers from earlier were still stuffed in my pocket, and every time I moved they crackled. In the end I took them out. Yet when I lay down again, the rustling noise was still there, coming from inside the coat. I checked the pockets again: both were empty.

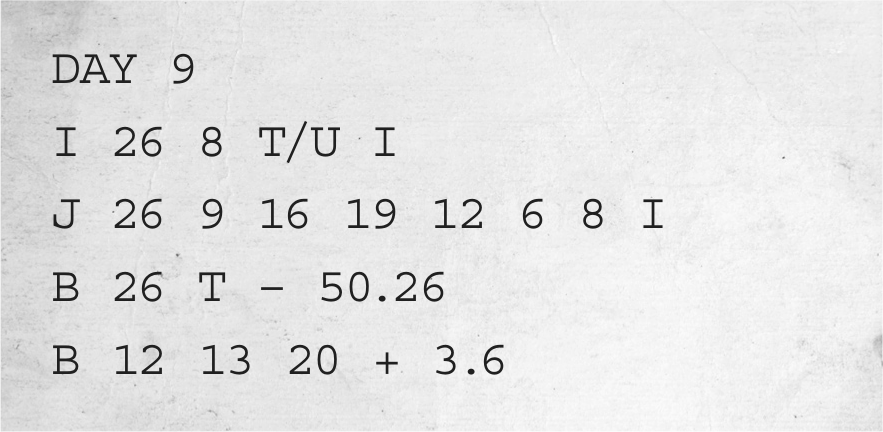

What I could feel was something stuffed into the lining. Intrigued, I sat up, lighting the remaining stub of candle. I was now able to see loose threads in the seam below the pocket. A slit big enough to put my hand in … and pull out a folded-up piece of paper, though at first it looked so wrinkled I thought it was a tissue.

Then I saw the writing – it was big and clear and nothing like Sukie’s own. It wasn’t a letter. I wasn’t actually sure what it was – and I spent a good few minutes staring at it. It looked like this:

I wondered if it was measurements, or a lock number, or a list of those plates that go on the front of cars. Yet the more I studied it, the more I felt uneasy, and certain.

It was some sort of code.