The first thing to disappear was the light itself. Starting that night, Budmouth Point lighthouse, the sea and the quicksands were to remain in absolute darkness. As promised, Mr Spratt came in person with the news but didn’t even stay long enough to sit down. Ephraim accepted his duty with a heavy heart, saving his true feelings for when Mr Spratt had left.

‘What a stupid idea!’ he raged. ‘Doesn’t he realise how deadly this coast is? We’re protecting no one by keeping the light off!’

There were other plans too, which Mr Spratt was ‘not yet at liberty to share’. It sounded ominous. Though I tried not to, I imagined awful scenes of people taking down the lighthouse brick by brick.

I didn’t like to say I’d only ever seen fishing boats go by. The coastline might be dangerous but it was also very quiet. Whoever used these waters – and someone did because the radio was often busy – was obviously doing so out of sight from us.

*

Cliff went to bed early that night. Knowing I’d not sleep I stayed by the stove trying to read, but my mind kept jumping in and out of the story. That word ‘erase’ really bothered me: as if you could just wipe out a person’s home and move them on somewhere else and expect life to pick up again as normal. Being evacuated had felt like that. You just had to get on with it and try to fit in. The Kindertransport, though, must’ve been so much worse because on top of everything else Esther had to learn a new language and new customs, which would have made the fitting in part doubly hard.

I shut my book with a sigh. I was trying to understand her, I really was. It wasn’t surprising she was angry – difficult, Mum would say. I wondered what Esther thought of me: was I annoying? Quiet?

Maybe.

Or was the uncomfortable truth that perhaps, from Esther’s viewpoint, it was me who was the angry, difficult one?

Mulling it over, I wasn’t really listening to Ephraim as he talked on the radio upstairs. But at some point I became aware that his voice was raised.

‘They were expected days ago, you know that. It was always going to be tough. With such a small window of time they’d have to be incredibly quick,’ he was saying.

‘No, I’ve not had any contact … no … not a word.’

I moved to the bottom of the stairs to listen properly.

‘The weather was set fair so that shouldn’t have been … She has the co-ordinates … Yes, I know the whole north coast is German-occupied, that’s why they had to act fast. And it’ll be dangerous landing a boat here without the light …’

He went silent. Somewhere in the crackle of the radio I detected a familiar woman’s voice – Queenie’s. It startled me for a moment, though it also made sense. My hunch from the other night had been right: whatever they were up to, they were in it together.

‘Patience, Ephraim,’ Queenie said. ‘We need to sit this out for a few more days.’

‘But it’ll only get harder, won’t it? Spratt’s got other plans for the lighthouse. He told me so this afternoon …’

‘Losing your nerve won’t help anyone,’ she insisted. ‘Look, it sounds like we need a meeting. I’ll contact the others. Come over as soon as you can.’

I only just managed to get back into my seat before Ephraim came rushing down the stairs.

‘I’m going out for an hour,’ he muttered, grabbing his oilskins from their hook.

‘Where?’ I tried to sound innocent.

‘Out,’ he repeated. The tension, still there in his voice, made me ever so slightly afraid. Whatever was going on involved a boat, and danger, and someone who’d been expected here but still hadn’t arrived.

Once Ephraim had disappeared, I shut my reading book. I really couldn’t concentrate any more.

*

Straight away the next morning I noticed the breakfast table hadn’t been laid. Normally, Ephraim left us porridge on the stove and a jug of fresh milk that came from Mrs Henderson’s goats. Today there was no porridge, no milk. The stove hadn’t even been lit.

Ephraim wasn’t here, either. After what I’d overheard last night, I doubted he’d been home at all: I’d been awake for ages and hadn’t heard him come in.

‘I’m starving,’ Cliff moaned, looking longingly at the stove. ‘I could eat a horse.’

I was hungry as well. We weren’t meant to touch anything, but we needed food.

‘Honestly, I’m going to die of starvation,’ Cliff went on. And on, moaning and clutching his stomach. It was starting to grate on me.

‘You’re not starving in the slightest,’ I snapped. ‘You don’t even know what starving is.’

‘And you don’t care!’ Cliff looked visibly hurt.

Feeling mean, I offered him a cup of tea, thinking that might help. But the kettle was cold and I couldn’t see a tea caddy anywhere. I grew steadily more frustrated.

‘You can’t do that!’ Cliff cried as I reached for the first cupboard.

I gave him a look. ‘Do you want breakfast or not?’

‘Course I do.’

Opening the cupboard door, I stepped back in complete surprise. Packet after packet of food tumbled out on to the floor. The shelves had been stuffed full.

‘Wow!’ I breathed.

‘Flaming heck!’ cried Cliff.

I’d never seen so much food, not in Queenie’s shop or even back home in the Lipton’s Tea Room on Edgware Road. There were tins of fruit and peas and peaches. Jar after jar of strawberry jam. Pickled vegetables, biscuits, packets of things that didn’t have labels on. Flour in sacks, rice, bags of sugar.

There was so much of everything – easily enough to feed twenty or thirty people, maybe more. Ephraim was expecting someone to arrive, that I knew, but I hadn’t realised quite how many ‘someones’ seemed to be coming.

Once I’d got over the initial shock, I wondered how we’d get all the food back in the cupboard again. The shelves under the sink were equally full: more tins. More rice. A basket of muddy onions. In the next cupboard there were dishes, plates, rolled-up bandages, a few pillows, some blankets.

‘Perhaps he got in extra knowing we were coming,’ Cliff suggested.

I shook my head. ‘Queenie sprang it on him, didn’t she? He didn’t know we’d be staying so I don’t think this stuff is for us.’

In the final cupboard, I found socks – twenty, maybe thirty pairs. There were scarves, hats, a few lumpy-looking sweaters. I couldn’t believe Ephraim had knitted all this – and for who? Unlike Mum and Gloria, he obviously wasn’t sending any of it away.

Downstairs, the front door slammed. We heard Pixie bark, then footsteps climb the steps.

Ephraim was back.

‘Quick! The cupboards!’ I cried.

We shut them quickly, quietly, one by one. Then we sat at the table, hearts pounding, just in time to calmly ask Ephraim if he’d got any food in for our breakfast.

*

‘I think you’re on to something,’ I said to Cliff, once we’d eaten and were in our room alone. Pixie was lying between us, nose on paws, grunting contentedly in her sleep. Now seemed a good time to share what I knew. ‘It’s definitely not for us, that stuff in the cupboards. He’s waiting for a whole load of people to turn up.’

‘Is he?’ Cliff propped himself up on an elbow. ‘Who?’

‘I don’t know yet.’

‘He was all nervous at the table just now,’ Cliff observed. ‘Did you see? He could hardly sit still.’

‘He didn’t come home last night, either,’ I remarked and told Cliff what I’d overheard last night on the radio.

‘Wowzers!’ Cliff was clearly impressed. ‘They’re like secret agents, aren’t they?’

‘No,’ I said firmly. ‘But what they’re working on sounds pretty dangerous. They had a meeting at Queenie’s with some other people too – I’m not sure who.’

It was all so mysterious. Sukie had disappeared; Ephraim was stockpiling food and waiting for a boat to arrive that was already days late, and I couldn’t think how that might link to our sister.

I had her note in front of me now, spread across my knee. Having a break from it hadn’t helped. It was still completely baffling.

‘Every time I look at this code it feels like a stupid dead end,’ I moaned.

‘Don’t look at it, then,’ Cliff replied. Getting off the bed he crossed to the window. The binoculars were on the sill where he’d left them. Staring out to sea was fast becoming one of his favourite pastimes.

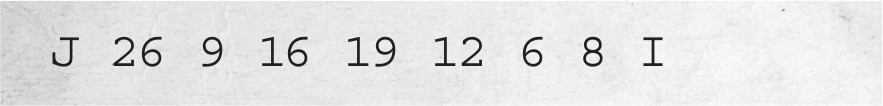

Narrowing my eyes, I tried the code again. I gave the first line a miss this time and started on the second:

Then the third.

All the way through, the highest number was 26. Which was the number of letters in the alphabet, wasn’t it?

I sat up straight. Could that be right? Could each number be a letter of the alphabet? Encouraged by the idea, I grabbed a pencil from my school bag and tried working out the second line: so 26 was Z, 8 was H. Though that didn’t explain the T or U or I.

I was just about to try the next line down when over by the window Cliff gave a long, low whistle.

‘Uh-oh,’ he said dramatically. ‘Olive, I think they’ve arrived!’