The suitcase wasn’t going any further. Waterlogged, it weighed a ton, and when we tried to move it even a few feet along the beach, we had to give up, panting. I knew Ephraim would want to see it, but there was no way on earth we’d get it up the lighthouse ladder.

‘I’m going to open it,’ I decided. Crouching beside it on the shingle, I flicked the catches. Cliff shuffled closer, breathing fast.

It’d probably once been an expensive piece of luggage. Now the sea had warped it and the leather was all scratched. With a gritty creak, the lid lifted. Inside were blouses, a few dresses – damp ones – with sandy, salty stuff caught in the folds. Tucked down the side were a couple of books. I couldn’t understand their titles; the words were in a different language. There was a pot of face cream, a toothbrush with its bristles splayed a little. I wondered who’d used it last – and where.

‘Is there a name on it?’ Cliff asked.

I pointed to the inside of the suitcase lid. There was a sticker that might once have said ‘Vienna’, which I knew was in Austria. In tiny writing underneath was an address I couldn’t read because the ink had all but washed away.

This suitcase belonged to someone. And that someone had packed up their books and clothes and toothbrush, much like we had, and had left their home far behind. I wondered if they’d felt frightened, unsure of where they were going and what sort of welcome they’d receive when they got there. At least we’d arrived in one piece.

The more I looked, the more I was sure this luggage was from Queenie’s missing boat. I could feel it too, a sort of foreboding in the air, because if my instinct was right, then where were the passengers? Had their attempt to help people gone tragically wrong? And what about Sukie? The awfulness of what this washed-up suitcase implied almost overwhelmed me.

‘Olive?’ Cliff tugged on my sleeve. ‘You’re crying.’

‘Am I?’ Quickly, I wiped my face on my sleeve. ‘Come on. Let’s go and tell Ephraim.’

We left the suitcase where it was.

*

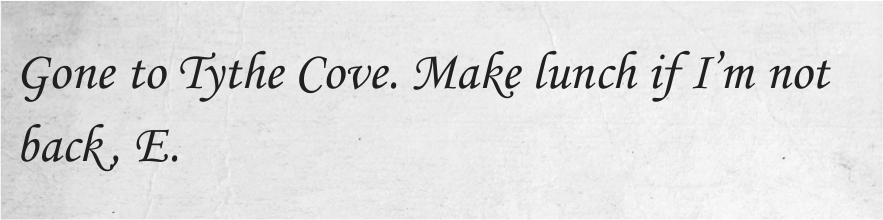

Back at the lighthouse, there was a note on the table.

Tythe Cove was the next village along the coast. You reached it by a path that went up steeply over the clifftops. I’d never walked it but could well imagine why Ephraim might want to: the views down on to the beach made it an excellent lookout for anything that might’ve washed ashore. And you’d not need to record your observations in a log book or mention it in conversation on the lighthouse radio. I only hoped he found something more cheering than a suitcase.

By the time we’d cleaned up and changed out of our sandy clothes, it was lunchtime and Ephraim hadn’t returned. I rather enjoyed rummaging freely in the kitchen cupboards and, finding parsnips and a bottle of banana flavouring, I made Cliff’s favourite mock-banana sandwiches. It was a total shock when he said he wasn’t very hungry.

‘Are you feeling all right?’ I asked.

‘My belly button hurts.’

‘You probably hurt yourself pulling me out of that quicksand,’ I told him. ‘A torn muscle or something.’

‘Have a look, will you?’ He pulled up his sweater, but I couldn’t see anything wrong with his belly button, apart from it being full of grit and fluffy grey stuff.

‘You need another wash,’ I said.

Yet by the time we put our coats on ready for school, he’d come out in a cold sweat so I insisted he go to bed.

*

As usual, the Budmouth Point kids were gathered at the school gates – not as many as there’d been that first day, but enough to remind me we were still a bit of a novelty. Today though, something else had their attention.

‘Listen to that engine. He’s in trouble,’ said a red-haired boy.

I heard the spluttering of what I thought was a broken-down van, until I realised they were looking at the sky. Moments later, the plane came fully into view. The black cross of the Luftwaffe, visible on its tail, made my stomach drop. So much for the camouflage paint protecting us: just like the others before him, this pilot was turning right, away from the open sea towards land, using the lighthouse to guide him.

It was obvious something was wrong with the plane. Thick black smoke trailed from the engine on the left. Flames were visible under the wing. There was another spluttering. Then silence. Another splutter. Silence. It was horrible yet compelling to watch.

About four hundred yards off the coast, the plane started losing height. It didn’t drop down gently, either. There was a terrific lurch. The whole aircraft shuddered. It veered left, then right, almost drunkenly. I was afraid it was going to keep going and crash into the village. The truth was worse: it wouldn’t make it that far.

Two hundred yards out to sea, the plane dropped further. The left wing dipped down. Straightened. The right one did the same. The horror of what was happening flashed before me: the German plane was on a collision course with the lighthouse. It’d never clear the top of the building. But it had to. Cliff and Pixie were still inside. Not that I could do anything, it was too late for that. I couldn’t even scream: my heart was jammed in my throat.

‘He’s aiming right for it!’ one of the Budmouth kids cried out.

‘Flipping heck! He’s going to hit it!’

‘He must have a parachute. Why doesn’t he bail out?’

I couldn’t watch. Yet I couldn’t bear not to. Shut up, I willed them all, hand pressed to my mouth, just shut up.

Everything slowed. The plane spluttered again, then seemed to bounce on the air. It came at the lighthouse almost level with the front door. I braced myself for the impact. The engine gave a dying roar. At the very last moment, it swerved right. Miraculously, it missed.

It took a moment for my brain to catch up. The plane was on its side, its left wing clipping the waves. With a final lurch, it dipped behind the rooftops and trees, disappearing from sight. Seconds later we heard a huge DOOF as it hit the ground. Fresh smoke billowed into the sky.

All at once everyone was trying to work out where the plane had come down.

‘It’s over by the Wilcoxes’ farm.’

‘No, it’s by the harbour, just past Jim’s house.’

‘I reckon it’s hit the woods.’

Still stunned, I didn’t much care where it was. Cliff being safe was what mattered to me.

At the school gates people from my class started appearing, Mr Barrowman amongst them. School, it seemed, had been forgotten.

‘Where’s everyone going?’ I asked a boy called Luke Mitchell.

‘To see the plane, of course.’ He grinned. ‘And what’s left of the pilot.’

It sounded a bit horrid, to be honest. Though I was intrigued to see what a German actually looked like, and I knew Cliff would want to hear the gory details. So I went with them.

*

Just beyond the harbour was a blackened hedge: the pilot had ploughed right through it, coming to a halt in the field beyond. The plane’s nose was buried in the ground, the tail sticking into the air. Pretty much everyone in Budmouth Point had come along for a look. The mood was wary, hushed, as if the plane was a sleeping dog that might suddenly wake up and bite. I should’ve been amazed at the sight of it, but instead it made me feel a bit uncomfortable to be gawping at someone else’s misfortune.

Just shy of the wreckage, the crowd stopped. Quickly word spread that the pilot wasn’t dead. He was sitting in the grass with a broken arm and you could see the bone sticking out through his shirtsleeve.

‘Do we tend him or leave him?’ asked Mrs Moore.

‘I don’t fancy touching him.’ This was Mrs Drummond.

‘Call the police,’ someone else suggested.

‘Or the coastguard.’

There was a lot of confusion, with no one really knowing what to do.

Then a familiar voice said: ‘I want to see his arm.’

I was aware of Mr Barrowman pushing past as he tried to grab someone’s coat collar. ‘Don’t stick your nose in, Miss Jenkins. Stay back here out of the way.’ But Esther was quicker than him, her dark pigtailed head soon lost in the crowd.

Everyone started shuffling forwards, moving closer to the aircraft as a group, as if there was safety in numbers. I shuffled with them, though the idea of seeing sticking-out bones was beginning to lose its appeal.

We came to a stop just in front of the aircraft. The smell of engine fuel was strong enough to make your eyes water. I could see the ground all churned up and the plane’s cockpit smashed on one side. It was incredible to think anyone had even survived.

Yet there he was, head bowed, kneeling on the grass maybe twenty feet away. The pilot’s uniform was in tatters. The damaged arm hung limp at his side. I didn’t see a bone, thankfully, but it was certainly bleeding badly. He was skinny in a way that made him look young – perhaps not much older than Ephraim. I’d not expected that; I’d not expected him to be crying, either. It made me more uncomfortable than ever.

The crowd now had the pilot surrounded.

‘Put your hands on your head where we can see them!’ This was Mrs Wilcox, the farmer’s wife, who looked scarier than any German.

But the pilot couldn’t lift his wounded arm. And he could barely stand, swaying dizzily and gasping in pain. He soon sank to his knees again.

‘He’s putting it on, don’t trust him,’ said a woman I didn’t know.

From the back of the crowd, someone shouted: ‘Spratt’s here. Let him through!’

A pathway opened up and the coastguard appeared, stern-faced and broad-chested.

‘Everybody calm down,’ he insisted, patting the air with his little hands. ‘We’ll deal with this situation. Go home now, please.’

No one moved. Just yesterday the locals had welcomed him like a hero: today’s mood was different. People folded their arms, shook their heads. It was, I had to admit, rather satisfying to see bewilderment on the coastguard’s face.

‘Painting the lighthouse didn’t work, did it, Mr Spratt?’ a woman in overalls called out. ‘The Germans still found it easy enough.’

‘Waste of bloomin’ time,’ old Mr Watkins agreed.

‘The painting isn’t yet finished.’ Mr Spratt quickly regained his composure. ‘Rest assured we’ll have the job completed by sundown today.’

My heart sank. This wasn’t going to help the missing boat one bit. What if it was still on its way from France? What if they were trying to find a lighthouse that didn’t appear to be there?

Mr Spratt’s answer didn’t quieten the crowd, either. If anything everyone moved closer to the pilot. Before I knew it I was just a few feet away. Mrs Wilcox and another woman were standing over him in a threatening manner. The pilot sensed it too, covering his head protectively with his good arm.

‘That’s for what you’re doing to our boys.’ Mrs Wilcox spat at him. The other woman prodded him with her foot. The pilot pleaded, using words I didn’t know. But he was sobbing – that I did understand.

‘Don’t!’ I burst out. ‘He’s injured!’

Someone told me to be quiet.

Surprisingly, Mr Barrowman stuck up for me: ‘Olive’s right. We should do things properly and follow international law. Hand him over—’

‘Oh belt up, Barrowman!’ snapped the fisherman who’d argued with Queenie yesterday. ‘The chap’s a German. When’ve they ever done anything properly, eh?’

Shouts of ‘Call the police!’ and ‘Give Jerry what for!’ rippled through the crowd. Yet still no one knew what to do. It infuriated me how Mr Spratt did nothing. He’d been so particular with Ephraim about the lighthouse, checking and double-checking the log book, yet now he very conveniently chose to look the other way.

I only hoped that when Dad’s plane came down someone kind had found him, to hold his hand when he was hurting and tell him not to be scared. Better still if it’d been so quick he’d died before his plane hit the ground.

No, I wouldn’t keep quiet. I had a voice, and it was time to make some noise with it.