‘German or not, the pilot’s a human being!’ I shouted over the general hubbub. ‘So are we – we’re not animals!’

Mrs Wilcox glared at me, unimpressed. ‘Who are you calling an animal, young lady?’

‘What I’m saying,’ I insisted, ‘is that we should treat him the same way we’d hope they’d treat a pilot of ours.’

‘There’s a war on, you stupid girl,’ the fisherman chipped in. ‘An enemy’s an enemy.’

‘Come here, Olive. Let the adults sort it out.’ Mrs Drummond tried to take my arm, but I shurgged her off.

‘Imagine if it was your son or brother, or … your father,’ I pleaded. ‘You’d want things done properly, wouldn’t you?’

For a few people that seemed to hit home. There were nods and sounds of approval. Then a hand grabbed me by the scruff of the neck, startling me. Mrs Wilcox pushed me towards the pilot.

‘Go on, then,’ she snarled, releasing me with such force I stumbled to my knees. ‘You sort it out.’

The German was so close I caught a whiff of something bloody, sickly, like a butcher’s-shop smell. I could see his injured arm properly now, except it didn’t look quite real. It was bluish-white bone, skin gaping and red like the inside of someone’s mouth.

The ground tilted beneath my feet, and the next thing I knew someone had pushed my head between my knees.

Mrs Henderson was beside me, her arm round my shoulders. ‘You had a little faint, lovey.’

And then a voice much louder than mine cut through the noise: ‘What on earth is going on?’

Everyone fell quiet. Looking up, I saw Queenie, hands on hips, her gaze flitting over the crowd. I felt rather silly for fainting.

She spotted Mr Spratt. ‘Did you allow this to happen?’ she asked in amazement.

‘Now just a minute,’ Mr Spratt protested. ‘I suggest you watch your tone—’

Queenie talked over his head: ‘You should be ashamed of yourselves, all of you.’

People stared at their feet, embarrassed. As Queenie made towards the pilot, Mrs Wilcox stood in her way.

‘Can I remind you that this is my land?’

‘And this is my country, Mrs Wilcox, during a time of war. So I’d advise you to step aside and let me escort the prisoner to where the military police can arrest him.’

Mrs Wilcox didn’t reply. I gulped uneasily, wondering if the mood of the crowd was about to change again.

‘If you don’t move out of my way,’ Queenie said frostily, ‘you’ll be in breach of international law, and with this crowd as my witness, I’ll be taking you to the military police, as well as our enemy here.’

The two women squared up to each other. Finally, with a terse sigh, Mrs Wilcox moved back. The rest of the crowd parted to let Mrs Henderson and Miss Carter through. They went straight to help Queenie, who was trying to get the pilot to sit up, but even the tiniest movement made him yelp in pain.

‘This arm needs a splint,’ Mrs Henderson was saying.

The ground swung a bit as I stood up, but as long as I didn’t look at the pilot I was fine.

‘The doctor needs fetching, Olive. Can you manage that?’ Mrs Henderson asked. ‘He’s called Dr Morrison and he lives in the last house before the church.’

I nodded: I knew where it was.

‘Good girl. Quick as you can.’

Glancing over her shoulder, I noticed Queenie crouched beside the pilot holding his hand. She was speaking to him very quietly. The one word I caught was ‘Nine’.

In a sudden moment of panic, I was sure she was talking about Sukie’s note. But then I twigged the tone of her voice: calm, clear, sensible.

Sukie once said we should learn a few German words just in case they invaded us. She’d taught us ‘no’ and ‘yes’, ‘please don’t shoot’ and ‘do you have oranges?’ So I knew ‘nine’ wasn’t just an English word. It was a German one too, spelled ‘Nein’.

*

True to Mr Spratt’s word, by sunset that day the paint job was finished. Budmouth Point lighthouse now looked like an enormous sandcastle, and was probably about as much use as one. Surrounded on all sides by grey sea, grey sky and an even greyer beach, it was devilishly hard to pick it out.

It made me ever more concerned for the missing boat from France. There were quicksands, rocks, all manner of hazards – Ephraim had told us. How awful it would be to escape the Nazis only to die the moment you hit the Devon coast.

As soon as I told Ephraim about the washed-up suitcase, he went off in search of it. Meanwhile Cliff said he still felt ‘iffy’ so Pixie belly-crawled under the blankets to keep him company, and I sat at the foot of his bed.

‘I saw the German pilot through the binoculars – he was trying to turn the plane so he didn’t hit us.’ Cliff looked flushed in the cheeks. I wasn’t sure if it was the excitement of the near miss or a nasty fever causing it.

‘Queenie spoke to him in German,’ I told him. ‘What d’you make of that?’

Cliff pulled a face. ‘That she’s clever?’

It wasn’t as exciting an idea as her being a double agent or spying for Great Britain, but it was probably nearer the truth. I was beginning to be rather in awe of Queenie. She had that quiet authority that made you respect her, even if she wasn’t overly friendly. Unlike Sukie, she didn’t need everyone to like her. In her old, baggy sweaters I don’t think she even cared. She simply did what she thought was right, and stuck to her guns. It was this, to me, that made her impressive.

‘Queenie’s convinced Sukie’s not involved in any of this,’ I mused. ‘What d’you think?’

But Cliff had already fallen asleep.

*

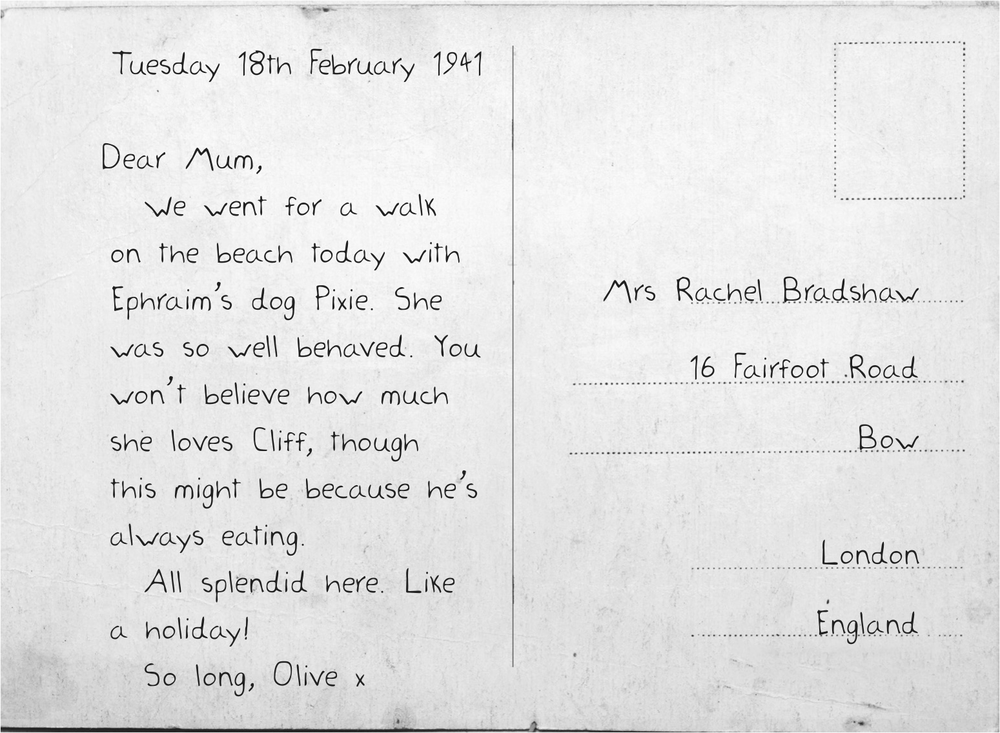

For a while I sat listening to the wind as it got stronger, making eerie whistling sounds at the windows. Then I started imagining huge waves crashing over a tiny boat, and whoever’s suitcase we’d found clinging on for dear life. Hoping to distract myself I wrote a quick postcard to Mum.

It was all lies, of course. Stupid, silly lies to stop Mum being sadder than she already was. Writing it didn’t slow my churning brain, either. So when Ephraim returned with the suitcase and called me to the sitting room, I took Sukie’s note with me.

*

The suitcase from Vienna sat dripping on the floor. With the oil lamps lit, the stove hot and the blackouts closed, it should’ve felt cosy. Yet from somewhere a chilly draught breathed around our necks.

‘The suitcase probably is from the French boat,’ Ephraim admitted miserably.

‘Or it could mean they’re very close,’ I suggested. ‘Maybe they’ve landed already?’

Ephraim shook his head. ‘It looks like it’s been in the water for a few days.’

Which made me more afraid than ever to ask about Sukie but I had to know whether Ephraim, like Queenie, thought she wasn’t involved.

‘When you wrote to my sister, what did she talk to you about?’ I asked tentatively.

‘Sukie?’ Ephraim rubbed the back of his neck, embarrassed. ‘That’s not really any of your business, Olive.’

‘Not the slushy stuff,’ I said quickly, feeling myself go red. ‘I meant anything about helping people trying to escape Hitler.’

‘Actually, she hasn’t written to me for a couple of weeks. I don’t know what I’ve said to upset her.’

I blinked; caught my breath. ‘You don’t know she’s gone missing?’

‘No!’ He was visibly shocked. It surprised me; since discovering their connection I’d assumed he knew – that he was part of it, even. ‘What happened? Tell me!’

So I told him about the night at the cinema. About the tall man she’d gone off to meet and how I’d followed her, until she noticed and got angry with me. I showed him the note. It was a sorry sight – smoke-smeared and water-stained, and still smelling of air raids.

Ephraim leaned forwards to take it from me, but I didn’t let go.

‘Queenie says Sukie’s not working with you,’ I said. ‘But I’m pretty sure she is.’

Ephraim shook his head. ‘She isn’t, Olive. Our contact in London was a Mrs Arby. She was nothing to do with Sukie.’

The name didn’t mean anything to me, either. I slumped back in my seat.

‘We chose Mrs Arby – we all chose her – because she was one of the best,’ Ephraim added. ‘It was such a difficult run, sailing overnight from the northernmost tip of France to here. And now without the lighthouse functioning and this dreadful weather …’ He stopped dismally, but I was keen to keep him talking.

‘Tell me about the code. How does it work?’

Ephraim glanced at the note in my hand. I still didn’t give it him, and I think he saw my determination: I wanted to crack the code myself.

‘Everything’s an opposite,’ he said. ‘Try it.’

Spreading the note over my knee, I studied it once again.

If the code worked on opposites then day would be night. And on a clock face the direct opposite of 9 was 3. Which must mean Day 9 was night at three. Three o’clock in the morning, the sort of time people did things they didn’t want anyone else to know about.

Opposites, I reminded myself: Day = night, so the opposite of the alphabet might be … numbers? Could A = 1, B = 2, right up to Z = 26? I tried it on the next line of the note, I 26 8 T/U I, swapping letters for numbers, and numbers for letters … until I ended up with a different code: 9 Z H 20/21 9. It still didn’t mean anything.

What if the numbers/letters idea worked as opposites, from A = 26 down to Z = 1? Each line started and ended with a letter. Were they opposites too? I tried swapping A with Z and so on, but that didn’t work either. I was stuck again. I went back to the opposites idea: day/night, light/ dark – yet it still didn’t seem to fit.

I’d always been rubbish at codes. Last summer holidays, Cliff and his friends invented one you had to read backwards in the mirror, and I couldn’t even break that. Though you’d hardly expect an important wartime message to be written in a simple schoolboy code.

Or would you?

I looked at the note again. Could the alphabet be a sort of reflection? If you halved it and went backwards … so A became M … Which meant the first line read as E 26 8 T/S E.

Now for the numbers. For my brain this bit was harder. Keep thinking backwards, I told myself. So I swapped all the numbers for letters, starting from the opposite end of the alphabet with 26 = A. The result this time was different:

I was getting somewhere. The message almost made sense, especially if you remembered that ‘East/SE’ was really ‘West/SW’. The last lines, looking like directions on a map, were also probably opposites. And it was obvious what ‘Darkhouse’ meant.

I wasn’t sure any of this was good news, though.

‘Well?’ Ephraim asked expectantly.

I shook my head. Cracking the code had confirmed my worst fears. ‘She was coming here. The note says “Darkhouse” and there are numbers like you get on maps. She was on the missing boat.’

Ephraim frowned: ‘That can’t be right.’

‘It must be. That man she met gave her the details and she hid them in her pocket, but then she lost the coat, didn’t she? So your boat full of visitors tried to make the crossing without the information. That’s why their journey went wrong.’

Ephraim blew out his cheeks.

‘Well?’ I asked. ‘That’s it, isn’t it?’

‘No, it isn’t.’

‘But I did the opposites thing you said and—’

‘Show me the note again,’ Ephraim demanded.

This time I handed him the piece of paper. He read it in seconds.

‘What d’you think it says?’ I asked.

Ephraim scratched his head so his hair stood up on end. ‘The boat was meant to come here, you’re right. But I still can’t see how Sukie would’ve got hold of this information.’

‘What do we do now?’

Ephraim stood up.

‘I need to speak to the others,’ he said, clearly agitated. ‘This changes everything. If the instructions never got to Mrs Arby in the first place, those poor people might still be in France. I dread to think what’s happened to them if that’s the case.’

‘So d’you believe me now? You think Sukie’s involved?’

He hesitated. ‘I really hope not.’

It was a grim answer. For it meant the boat I was certain my sister was on was unlikely ever to arrive.