Cliff was just waking up as I got in.

‘Is Sukie here?’ he asked.

Desperate as I was to fall into my bed I sat on his, trying to decide what to tell him. Sukie hadn’t arrived and it seemed I was the only one who’d expected her to. Yet no one could explain why she’d had the coded note, and now, to top it all, Miss Carter was acting strangely.

‘Did the Jewish people come too?’ Cliff peered at me, bleary-eyed.

‘Yes,’ I replied, happier to talk about this. ‘They made it, and you’ll never guess what, but Esther’s dad was with them. She’s completely over the moon.’ I told him about the ballerina with the lovely name and the family who made puppets and the old ladies with rain-splattered glasses.

Cliff shut his eyes again. ‘Really? Sounds nice.’ He didn’t seem to be listening any more.

It concerned me that he wasn’t getting better. If anything this morning he seemed worse.

‘Is your belly button still hurting?’ I asked.

‘The pain’s here now.’ His hand hovered over his right side. Suddenly he tried to sit up. ‘Quick! I’m going to be sick!’

I found our chamber pot just in time. Poor Pixie didn’t like the retching sounds and hid under the bed.

‘You need to see a doctor,’ I told him, when he’d finished. ‘As soon as Ephraim gets home we’re taking you. And that’s an order.’

Luckily, Ephraim was back within half an hour. After wrapping Cliff in a blanket, we realised he was too ill to even stand.

‘Right.’ Ephraim braced himself. ‘Let’s get him down.’

I watched in horror as he heaved Cliff on to his shoulders. It was exactly how he carried Pixie down the ladder. I didn’t think I could bear to watch. ‘Shouldn’t we get the doctor to come here?’ I asked anxiously.

But Ephraim already had one foot on the ladder. Pixie, cross at being left behind, whined and scratched at the front door. What with that and Cliff’s groaning, I was very glad when we made it safely on to the ground.

‘Try not to cry,’ I told Cliff, giving him a quick hug. ‘You’ll soon be better.’ He really didn’t look good, though.

Between us, Ephraim and me carried him out of the harbour and up the hill. Cliff wasn’t heavy exactly, but we were trying to hurry and at the same time not hurt him, so it was arm-achingly awkward.

At last, we turned towards the church. The house just before it – red-brick, severe-looking – was Dr Morrison’s. His housekeeper showed us into a stuffy room that smelled of cigars. Very gently, we lowered Cliff on to a chair. The pain nearly made him pass out. When the doctor joined us, he was still chewing what I guessed was a mouthful of his breakfast. He looked in a hurry to get back to it too.

One by one, I reeled off Cliff’s symptoms. It was quite a list – in normal circumstances, my brother would’ve been rather impressed.

‘There’s a nasty stomach upset doing the rounds,’ Dr Morrison told us. ‘I suggest you take him home and put him to bed.’

I stared at him in surprise. ‘Aren’t you going to examine him?’

‘Examine him?’ the doctor said tetchily. ‘My dear, I can spot a stomach upset at fifty paces.’

*

Out in the street, I couldn’t contain my anger. ‘A stomach bug? What twaddle! I bet he doesn’t treat his local patients like this!’

Cliff was getting worse before our eyes. Even breathing seemed to hurt him now.

‘What the heck should we do?’ I was beginning to despair.

‘There’s a woman in the next village who uses herbs,’ Ephraim offered.

Herbs?

‘Blimey, it was just a suggestion,’ Ephraim muttered, reading my expression.

‘What about Dr Wirth?’ I said, suddenly. Queenie’s – where we’d find him – was just a few doors down the street.

*

Dr Wirth was in Queenie’s kitchen, discussing with Esther how best to wind up the stopped clock. One look at Cliff and the doctor got to his feet.

‘I’ll wash my hands,’ he said.

While Dr Wirth prodded Cliff and listened to what Ephraim told him, I slipped into a seat opposite Esther. She didn’t speak or smile or do anything pally. But things did feel different between us, like we’d accepted each other’s right to exist.

‘This young man needs an operation urgently,’ Dr Wirth said, once he’d finished his examination. He had the same slightly husky accent as Esther. ‘His appendix is about to rupture, and if that happens …’ He made a horrible exploding gesture with his hands.

I wished Mum was here.

‘Where’s the nearest hospital?’ Dr Wirth asked.

‘Plymouth,’ said Ephraim. ‘About twenty miles away.’

‘We must get him there as quickly as we can.’

*

Mrs Henderson, it turned out, knew a goat farmer with a van. In next to no time, a tall, robust man, called Mr Fairweather arrived, and in one swoop hoisted Cliff out of his chair.

‘You weigh no more than my best Anglo-Nubian, you don’t,’ he said cheerfully. He’d put fresh straw down in the back of his van, and a clean bucket: ‘In case your guts don’t hold, lad,’ Mr Fairweather told Cliff. His kindness made me want to weep.

As I went to climb into the van beside Cliff, Ephraim stopped me. ‘He’ll need an adult with him at the hospital. I’ll go.’

‘I can’t leave him,’ I protested.

‘You’ve done your bit, Olive. Now let the doctors do theirs.’

Frustrated, I felt myself welling up. ‘He’s my brother. He needs me. He’ll be frightened on his own,’ though he probably wouldn’t with Ephraim looking after him.

‘Hurry up, you two,’ Mr Fairweather called from the driver’s seat.

‘Take care of Pixie for me.’ Ephraim got into the van before I could argue any more. ‘I’ll let Queenie know any news. Try not to worry.’

I stepped back on to the pavement, defeated.

Yet watching the van disappear up the street was almost a relief. I couldn’t do any more. I couldn’t help Cliff get better, nor could I make Sukie appear on a boat. I felt overwhelmingly tired. All I wanted was Mum to smooth my hair off my forehead and tell me everything would be fine.

Back inside, Queenie was about to open the shop for business. I’d expected her to be dead on her feet like me, but she was humming a tune under her breath. and her eyes were twinkling, almost smiling.

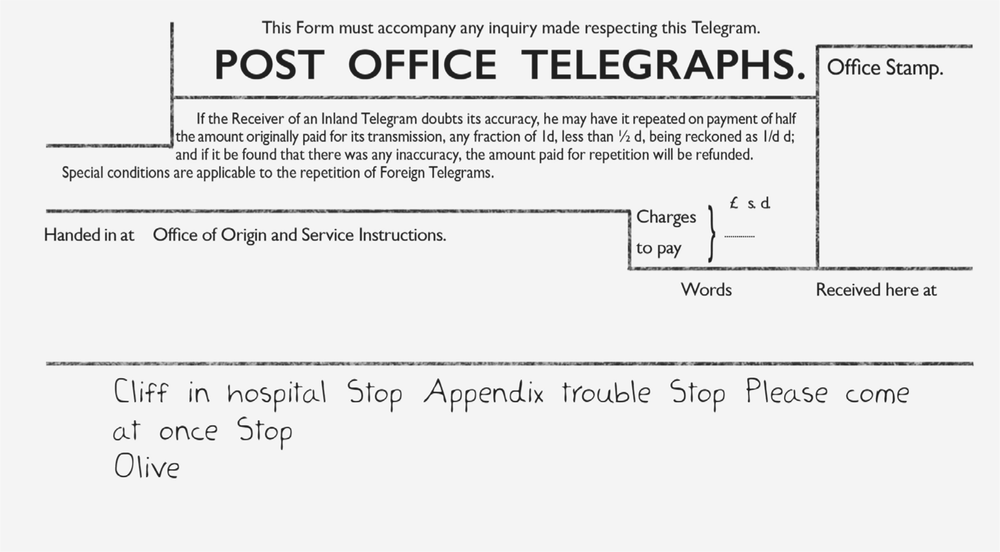

‘I need to send an urgent telegram to London, please,’ I said, trying hard not to stare.

Taking a form from a drawer, Queenie passed it to me with a pen. ‘Keep it brief,’ she instructed. ‘You pay by the word.’

In the ‘message goes here’ box, I wrote:

Mum arrived from Paddington on the 4.30 p.m. express. I went to the station to meet her, taking Pixie, who needed the walk. Throwing my arms around Mum’s neck, I breathed in her familiar lily of the valley smell and felt relieved.

‘Gosh, what a welcome!’ Mum stepped back anxiously. ‘Is there any more news? I telephoned the hospital before I left and Cliff was just going to theatre.’

‘He’s fine,’ I reassured her. ‘Ephraim just called to say he’s in recovery. He’s allowed one visitor tomorrow.’ We both knew that visitor would be Mum.

It was a shock to see how thin she’d got since we’d said our goodbyes just over two weeks ago. She’d put on her make-up more heavily than usual; it didn’t suit her. I wondered if I’d done the right thing, bringing her all this way when she still wasn’t well. But it was too late to worry about that.

‘This is Pixie,’ I explained, trying to cheer things up. The little dog did her best, the dear thing, squirming in delight and rolling over for a tummy tickle.

Mum smiled. ‘She’s adorable.’

‘Cliff loves her. He’ll be wanting his own dog when we come home.’

‘We’ll see.’ Straightening up from stroking Pixie, Mum narrowed her eyes at me. ‘You’re not sleeping, are you? You look tired.’

‘So do you, Mum,’ I replied.

Slipping my arm through hers, I took her to Queenie’s, which was closest, and told her all about Dr Wirth as we walked.

*

At Queenie’s, Mum insisted on shaking Dr Wirth by the hand.

‘I cannot thank you enough for what you did for my boy,’ she gushed. ‘Olive tells me you saved his life.’

‘Kindness repays kindness,’ he replied. And he gave her a very sincere handshake in return, holding her hand in both of his, which made Mum go rather red-faced for some reason.

As I organised some tea, the kitchen became busy. Mr Geffen the violinist joined us at the table, then Miss Zingari, the ballerina, who insisted on pouring our tea and handing round the biscuits. Anna and Rosa Schoenman told Mum, in faltering English, that they’d made up a play with puppets about their journey and would she like to watch? Mum looked genuinely delighted – and it was lovely, if a little unexpected, to have such a warm welcome.

A quick, cheery knock at the back door announced Miss Carter’s arrival. ‘Hullo! Is Queenie here? I’m just … Oh!’ The sight of Mum made her visibly jump.

‘We meet at last,’ Mum said coolly, putting down her teacup.

‘You’re here!’ Miss Carter gasped. ‘How?’

‘By the Paddington train.’

Miss Carter seemed a bit thrown. So was I by her reaction: it was certainly odd.

‘It’s a great honour,’ Miss Carter said hurriedly. ‘You look just like your photograph.’

My confusion grew as she came into the kitchen and, wiping her palm on her slacks, went to shake Mum’s hand; Mum didn’t take it.

‘Oh.’ Miss Carter withdrew her hand.

It was horribly awkward. I liked Miss Carter, who’d always been nice to me, and couldn’t understand why Mum was being so rude. I wasn’t the only one who’d noticed, either. Dr Wirth, getting up from the table, gestured to the other refugees that it was time to leave the room. As the door closed behind them, the kitchen became ominously quiet.

‘Do you two know each other?’ I asked warily.

‘Yes.’ They both said it at the exact same time.

I glanced at Mum, who seemed suddenly fierce. In contrast Miss Carter looked terrified. Something was definitely going on between them. The only connection I could think of was Sukie.

Now I was nervous. ‘How do you know each other, exactly?’

‘Through work,’ Miss Carter said. ‘Though we haven’t met in person until now. It’s rather sensitive, the work we do, so the fewer the better.’

I didn’t understand what she was saying. Mum worked in the printworks in Whitechapel; she’d done so for ages.

‘But Miss Carter helps rescue refugees,’ I pointed out to Mum.

‘Yes,’ Mum replied. ‘She does.’

She spread her hands on the table, where I could see they were trembling.

‘Miss Carter,’ she said. ‘Why don’t you pull up a chair?’

Reluctantly, Miss Carter sat across the table from Mum. She fiddled with an empty teacup, unable to look either of us in the eye. It came to me again, in a rush. Miss Carter was the ‘man’ my sister met, wasn’t she?

‘You gave Sukie the note that night, didn’t you?’ I said outright.

For a moment, I thought Miss Carter was going to deny it. Then her face crumpled and she burst into tears.

‘I made a terrible error. It was too dark, that night, too wet. I read the code wrong and told everyone here the wrong date, didn’t I?’ she sobbed, taking off her glasses. ‘This stupid mess is all my fault.’

In that moment I didn’t know whether to hug her or hate her. Because of her mistake, my sister was missing. But I sensed there was more.

‘Who’s this Mrs Arby you all keep talking about?’ I demanded. ‘Were you supposed to give the note to her?’

Mum blinked. ‘Mrs Arby?’ She said it differently to the others – not ‘Arby’, with the stress at the start of the name, but ‘RB’, like initials.

I stared at her.

RB.

It was obvious. Sukie, dressed in Mum’s coat, with her hair styled glamorously, looked older – old enough to pass for Mrs Rachel Bradshaw. In the chaos of the air raid, it’d been an easy mistake to make, getting a person’s identity wrong. Which meant the mysterious Mrs Arby, the London contact who everyone trusted, who’d done jobs like this before, was Rachel Bradshaw.

My mum.