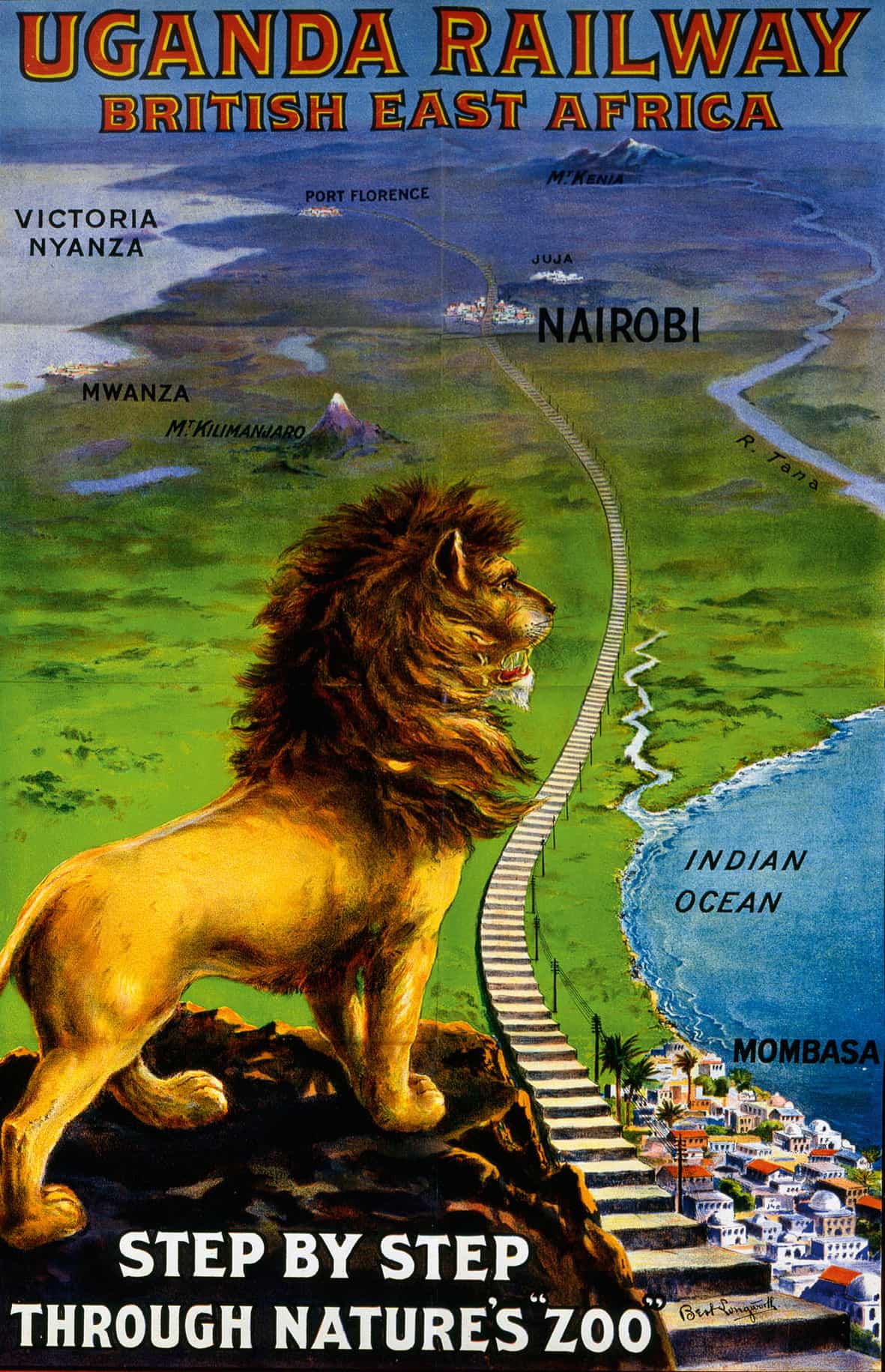

1908 Uganda Railway poster, showing the track from Nairobi to Mombasa.

Mary Evans

German school pupil with a Maasai boy, 1938.

Topfoto

By 1850, the likes of Portugal, the Netherlands, Britain and Germany had been using the East African coast as a staging point along the trade route between Europe and India for longer than three centuries. With the arguable exception of Portugal, however, none of these European powers had demonstrated any significant interest in territorial expansion beyond a few isolated coastal ports. Likewise, the East African interior, although it was regularly traversed by Swahili slave caravans as far inland as the great lakes, remained a cartographic mystery to European geographers.

All that would change in the second half of the 19th century, an era of terrestrial exploration that resulted not only in the mapping and opening up of the entire African interior, but also in most parts of the continent being colonised by, or entering into treaties as protectorates with, one or other European power.

Mapping the interior

In 1846, the German missionaries Johann Krapf and Johannes Rebmann established an evangelical mission in the Taita Hills, and went on to become the first Europeans to see the continent’s two tallest mountains, Kilimanjaro and Kenya, though their reports of equatorial snow caps were initially disbelieved back home. However, the main impetus for further exploration of the interior was the so-called slug map produced by another German missionary, James Erhardt, in 1855. Based on third-hand accounts from Swahili traders, this map was nicknamed for the large slug-shaped lake it depicted at the heart of the continent, which – though wildly inaccurate – generated fresh interest in a mystery that had tickled geographers since Roman times, namely the location of the source of the White Nile.

Within five years of the slug map’s publication, the continent’s three largest lakes had all been freshly ‘discovered’ by Europeans – Lake Niassa-Malawi by the Scottish missionary David Livingstone, Lake Tanganyika by Sir Richard Burton and John Speke, and Lake Victoria by Speke alone. The relationship between these three lakes and the Nile remained a matter of conjecture, with Speke controversially nominating Lake Victoria as the great river’s source, while Burton, Livingstone and most other geographers favoured Tanganyika. The controversy was settled only in 1875, when Henry Stanley circumnavigated both lakes and established that Tanganyika was part of the Congo watershed.

Joseph Thomson gained a reputation among the Maasai as a great laibon, or ‘medicine man’. His repertoire of tricks included frothing at the mouth with the help of Eno Fruit Salts and the removal of two false teeth.

Most of the Kenyan interior remained unexplored at this point, largely because these explorers travelled inland along slave caravan routes that mostly left from ports south of the present-day border with Tanzania, but also because of the Maasai’s renowned hostility to outsiders. The first European expedition into Maasailand was undertaken in 1882 by Gustav Fischer, who was forced to turn back to the coast when he was ambushed by the Maasai at Hell’s Gate near Lake Naivasha. The British explorer Joseph Thomson, who followed in Fischer’s footsteps a few months later, became the first European to document the existence of Lake Baringo and Mount Elgon, as well as the waterfall outside Nyahururu that still bears his name.

The first European visitor to northern Kenya was Count Samuel Teleki, a Hungarian aristocrat who hiked to an altitude of 5,350 metres (17,552ft) on Mount Kilimanjaro and 4,725 metres (15,502ft) on Mount Kenya, before heading northwards to Lake Turkana, which he reached in 1888. Arthur Donaldson-Smith became the first European visitor to Mount Marsabit in 1895, and Captain Stigand was the first to cross between these two northern landmarks via the Chalbi Desert in 1909.

The build-up to colonisation

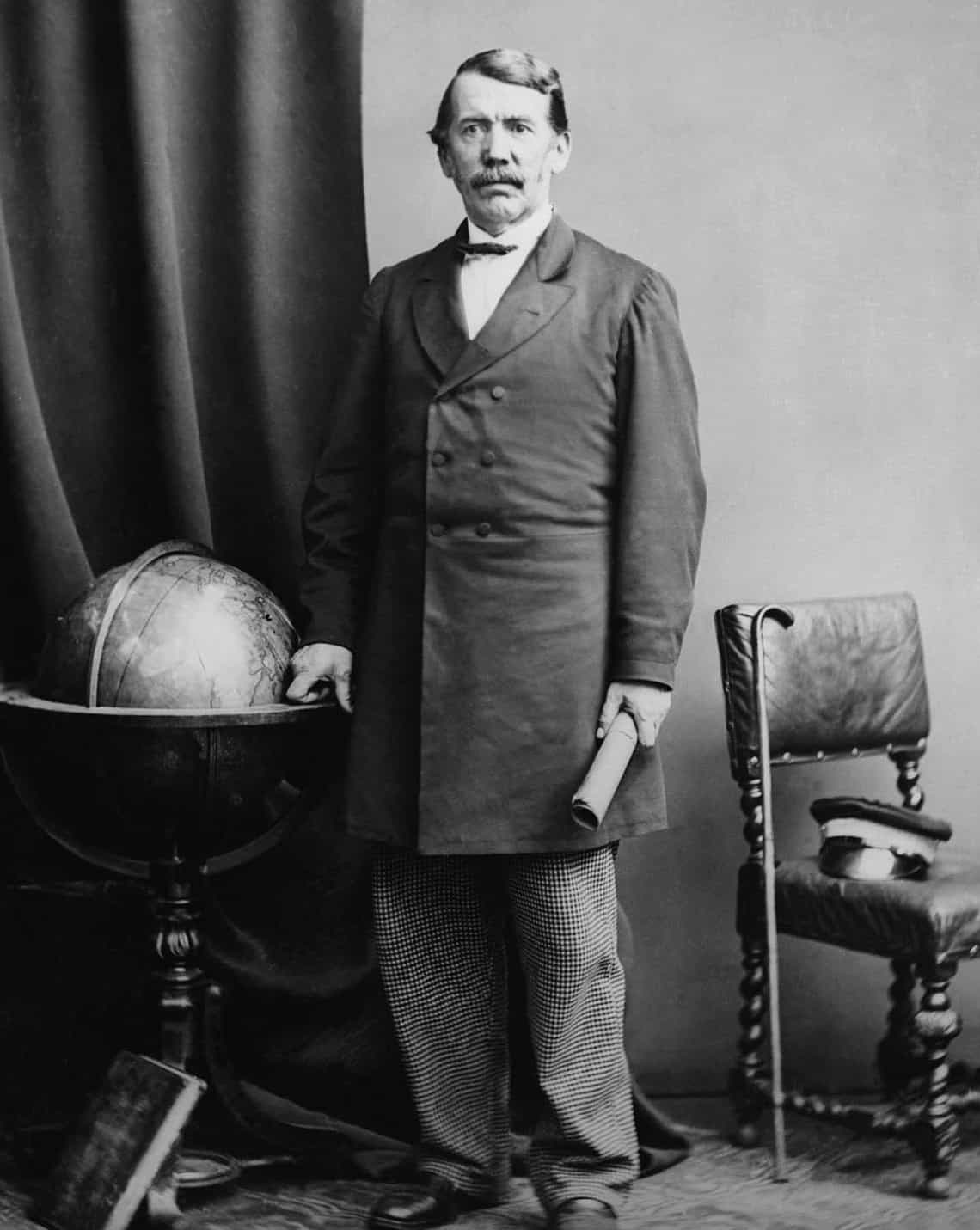

Although hindsight lends the colonisation of East Africa a certain aura of inevitability, it was an unexpected turn of events at the time, one entered into with mixed motives and little premeditation by the concerned European powers, of which Britain was dominant. Nor were British motives for colonisation as entirely self-serving as is often assumed. Indeed, a major advocate of colonisation was the anti-slaving lobby, whose attempts to stop the flourishing coastal trade in human lives were galvanised in 1872 by the emotional funeral of the explorer David Livingstone, an outspoken abolitionist who had ample opportunity to witness the unspeakable cruelties perpetrated by the slavers along the caravan routes he followed into the interior.

The Victorian explorer David Livingstone led numerous expeditions in Africa.

Corbis

Livingstone and his supporters believed that the slave trade could be halted only by opening up the African interior – where murderous slave raids generally resulted in entire villages being razed, as all their inhabitants were either killed or taken captive – to the ‘three Cs’: Christianity, Commerce and Civilisation. And it was in the wake of Livingstone’s funeral that Britain took its first step towards colonisation, formalising its already strong links with the dominant regional power Zanzibar in 1873. A naval blockade was placed around the island, and the British consul John Kirk, a former travel companion of Livingstone, persuaded Sultan Barghash (the son of Seyyid) to sign a treaty offering him full British protection against all other foreign powers if he banned the slave trade. As a result, Barghash closed down Zanzibar’s notorious slave market, and allowed an Anglican Church to be built on the site.

The partitioning of the East African mainland was initiated by the German premier Leopold von Bismarck, whose main interest in the region was probably to acquire pawns to use in territorial negotiations with Britain and France closer to home. In 1884, based on a series of questionable treaties acquired by the German metaphysician Carl Peters, Bismarck announced claims to a large tract of land between the Pangani and Rufiji rivers in present-day Tanzania. Since large parts of the area claimed by Germany were conventionally regarded to be part of the Zanzibar Sultanate, Britain was bound to protect them in accord with the treaty signed with Barghash in 1873, especially as failure to do so might result in it losing control of Zanzibar’s lucrative import and export trade, which generated an annual turnover of two million pounds.

Heliogoland-Zanzibar Treaty

In 1886, as the so-called Scramble for Africa hurtled towards its hurried climax, Britain and Germany agreed to a coastal territorial partition that corresponds to the modern border between Kenya and Tanzania. An administrative and trading concession, covering the whole coast from Vanga to Kipini, was granted to the Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEAC) under a Royal Charter in 1888. However, this agreement didn’t set a northern or western border for the British sphere of influence, which allowed Germany to claim a block of territory north of the Tana River (including the Lamu archipelago) in 1890, along with much of what is now Uganda.

By this time, Bismarck had resigned as German premier, paving the way for his successor Leo von Caprivi to knock out the amicable Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty with his British counterpart Lord Salisbury. This treaty affirmed British protectorateship over Zanzibar, as well as German possession of what is now mainland Tanzania, Burundi and Rwanda. In addition, Salisbury surrendered the tiny but strategic North Sea island of Heligoland (which had been captured by Britain in the Napoleonic Wars), in exchange for which Germany revoked all its claims to parts of present-day Kenya and Uganda, and both parties agreed that the coastline to a depth of 10 miles (16km) should remain part of the Zanzibar Sultanate, a British Protectorate. (It was to stay this way right up until the independence in 1963, when Sultan Seyyid Khalifa ceded his mainland territory to Kenya.)

British East Africa

In July 1895, the virtually bankrupt IBEAC was rescued by the British Government, which bought the company assets for £200,000, and took over what is now the territory of Kenya as ‘British East Africa’. The Sultan in Zanzibar was paid an ‘honorarium’ of £17,000 a year for British protection of his 16km (10-mile) long strip of coastline. The news that the British Crown had taken over from the IBEAC angered many locals, in particular the prominent Mazrui family, which had never fully acknowledged Omani rule over the Sultanate of Zanzibar, and which led organised attacks on Mombasa and Malindi as part of a unilateral declaration of independence for the coastal strip. These uprisings were dealt with by detachments of the British Army brought over from India.

The people of the interior – few of whom would even have heard of Britain ten years earlier – proved to be equally unwilling to accept their new colonial masters. It took four military expeditions, for instance, to persuade the Kamba tribe to accept the British administration. Further up-country, more troops were garrisoned at Fort Smith to control a territorial expansion of the Kikuyu out of the highland forests. Around Lake Victoria, the Nandi and other tribes began a guerrilla resistance in 1895 which was to last over 10 years until the Nandi laibon, spiritual leader and chief strategist, was shot dead at peace talks.

Only the Maasai came into the Protectorate of their own accord. At that time they were having difficulty dealing with predatory raids of the Kikuyu and Kamba since the prophesied plagues of rinderpest and smallpox had seriously weakened them. In the north, a revival was started with food-aid cattle from the Protectorate and a couple of seasons of good rain. The Maasai moran (warriors) picked themselves up and replenished the tribe with cattle and women collected in reprisal raids against the Kikuyu, and the Meru and Embu on the eastern shoulder of Mount Kenya.

By the end of 1895, the British rated the Maasai ‘a menace and a force to be reckoned with’ after they massacred half a caravan of 1,100 men in the Kedong section of the Rift Valley above Nairobi. A passing trader, Andrew Dick, decided to exact retribution on behalf of the Crown. He attacked the Maasai sentries guarding the cattle, made off with a large herd, and was halfway up the eastern escarpment before the main body of the moran caught up with him. Trader Dick was thus added to the casualty list, which also included 452 Kikuyu and 98 Swahili. At the official Court of Inquiry, the Maasai were found to have been unreasonably provoked but were charged compensation for the massacre in the amount of the cattle taken by Dick.

Kenya and Uganda Railways freight train, Mombasa.

Getty Images

Economic growth

A Scotsman, Sir William Mackinnon, the former chairman of the IBEAC, brought the first scheduled steamship line to the East African ports and built a road from Mombasa upcountry to Kibwezi. He also advocated the construction of a railway line from Mombasa to Lake Victoria The original purpose of the line was strategic, to get a permanent line of communication into Uganda ahead of the Germans coming up from the south. A vocal opposition group in the British Parliament called it a monumental waste of time and money, ‘a lunatic line to nowhere’. But the scheme went ahead in 1896, with the import of 32,000 Indian labourers from Gujarat and the Punjab.

The single-track railway from Mombasa to Lake Victoria covered 935km (581 miles) and cost the British taxpayer £9,500 a mile, which is equivalent to almost £1,000,000 per mile in modern terms.

In May 1899, a temporary halt to railway construction was called at mile peg 327, and a tented depot was established at the site, now the city of Nairobi, but then a dank, evil-smelling, frog-infested swamp, where wildlife wandered in from the Athi Plains. The Maasai stayed aloof from the new encampment, but the Kikuyu came in to market their crops and livestock. The first coffee was planted by Catholic priests at St Austin’s Mission on the outskirts of the township, and tea was started on the wooded uplands of Limuru close to the 600-metre (2,000ft) precipitous drop into the Rift Valley. This, the worst of the natural obstacles in the way of the line, was negotiated first by a funicular system of cables and winches. Later a zigzag slant was cut out on the face of the scarp. From there on it was fairly easy going across the Rift floor, up the gentler wall of the Mau Range to an English country landscape around Njoro, and on down to the shores of Lake Victoria. The last spike was driven in at Port Florence (Kisumu) on 19 December 1901, just over five years after construction started.

Boosted by the rail link to the interior, Mombasa rapidly took over from Zanzibar as the main regional trade centre. But while the railway brought prosperity to Mombasa, the companies resident there soon acknowledged that their future lay in Nairobi. As they moved up the line, so did the planters’ association, the commercial associations and, finally, the colonial administration, which decided to make Nairobi the colonial capital in 1907.

Sir Charles Eliot, the Commissioner of British East Africa from 1900 to 1904, decided that the huge cost of the railway should be recouped through European settlement along the line, wherever the land could be farmed or ranched. The Scottish-looking Aberdares, with their cool climate and fertile valleys, offered the best prospect for arable development. Several of the first farmer-settlers were the rootless younger sons of the minor British aristocracy. In a sense, these ‘White Highlands’ became the officers’ mess of colonial Africa, with the Asians barred from owning land in the area and the Kikuyu either retained as labourers or asked to remove themselves to a patchwork reserve on the range’s lower eastern slopes. Elsewhere, albeit to a lesser extent, local tribes were forced to make way for white settlers, with the likes of Lord Delamere, for instance, being granted a tract of ranchland in the vicinity of Lake Elmentaita, forcing its Maasai residents either to take up employment on the ranch, or to vacate it for a designated tribal reserve.

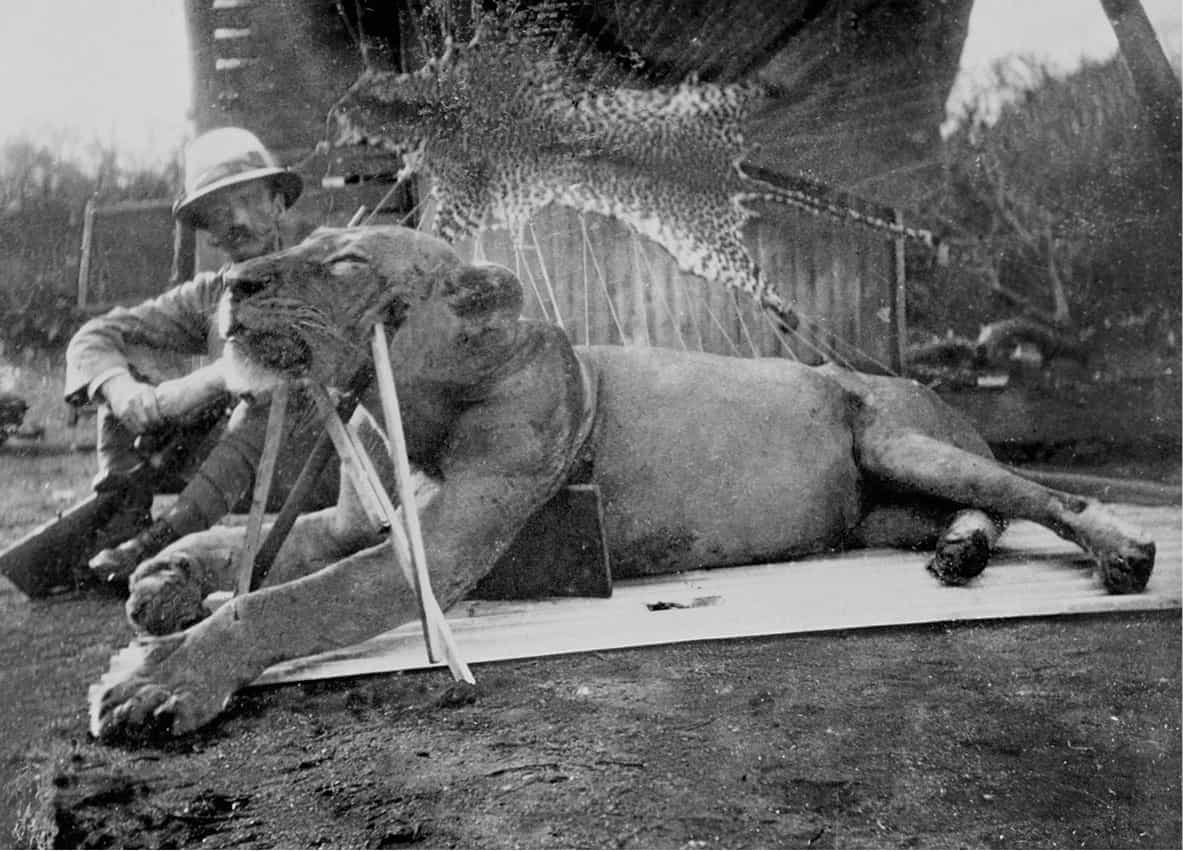

Lt. Col John Henry Patterson poses with the body of one of the man-eating lions he shot and killed near the Tsavo River, late 1890s.

Getty Images

The man-eaters of Tsavo

While the railway was being built across the Tsavo plains, a pair of elderly male lions developed a taste for the workforce, killing at least 30 Indian and African labourers, and possibly as many as 135, between March and December of 1898. Several explanations have been put forward for this unusual behaviour, one of the most credible being that it was due to a shortage of normal prey created by a severe rinderpest epidemic. Another theory is that their taste for human flesh was acquired by scavenging improperly buried bodies of malaria victims associated with the railway. Whatever the reason, the two lions – named ‘The Ghost’ and ‘The Darkness’ by terrified railway workers – were legendarily skilled at avoiding traps and barriers, and in one instance they actually boarded a train to drag off their victims.

The lions were eventually shot by Lt Col. John Henry Patterson, whose book about the lion attacks has inspired several movies, notably Bwana Devil (1952), Killers of Kilimanjaro (1959) and more recently The Ghost and the Darkness (1996, starring Michael Douglas and Val Kilmer). The country on both sides of the track was left as a wildlife reserve, later to become Tsavo East and West national parks.

War in Africa

World War I boosted the colonial economy, with troops and goods from overseas moving through the port of Mombasa. It also had a huge political impact on British and German East Africa, neighbouring territories administered by the war’s two main adversaries. At first the African campaign was a series of minor episodes. The German commander in Africa, Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, defeated the British embarrassingly at Tanga and then led a hit-and-run campaign against the railway supply line from behind the Taita Hills.

Army Scouts making their way through the forests of East Africa during World War I.

Alamy

Two-thirds of the British colony’s 3,000 male settlers left their wives to manage the farms while they rode after Germans in irregular cavalry units. The colonial government also made strenuous attempts to conscript the Maasai and other locals into the regular army. The British successfully attacked the German post at Bukoba, in the west shore of Lake Victoria. Then, led by the South African general Jan Smuts, they drove Vorbeck into a fighting retreat around Central Africa, thereby allowing the German general to achieve his main objective of occupying a large force of the British Army for the duration of the war. He was leading 155 Germans and 3,000 Africans into Portuguese Angola in November 1918 when he received news of the armistice.

Vorbeck ended the war undefeated, but Germany lost Tanganyika in the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. Britain was assigned to govern the larger part of it under a League of Nations mandate, and began thinking of an economic federation of the three East African territories.

White settler and two boys operate farm machinery, c.1940.

Corbis

The ‘Colony of Kenya’

Another significant consequence of the war was the British Government’s decision to offer estates in the highlands to veterans of the European campaign in what was called the ‘Soldier Settlement Scheme’. By 1920, when the country was designated the ‘Colony of Kenya’, the white population was around 9,000. The coastal strip remained detached for a few years on a courtesy lease from the Sultan of Zanzibar.

All this advanced the settler community’s objective of a permanent white man’s Kenya – but they were soon disillusioned. A Government White Paper in 1923 introduced a policy of ‘Africa for the Africans’. In what was seen as a Bill of Rights for the black Kenyans, the key paragraph stated that, ‘Primarily, Kenya is an African country. H.M. Government think it necessary to record their considered opinion that the interests of the African native must be paramount, and that if and when those interests and the interests of the immigrant races should conflict, then the former should prevail.’

From then on a succession of colonial governors were obliged to apply the paper policy, often facing abusive opposition from a settler community led by Lord Delamere and his National Legislative Council. A takeover attempt by the settlers was always a possibility, but there were never enough of them for any open rebellion or for the political fight, which was probably lost when the administration’s power base at Nairobi began a rapid expansion from the mid-1920s. This led to a major social revolution for the adaptable Kikuyu, who flocked to the fledgling city, in the process making a giant leap from a traditional African lifestyle to a more cosmopolitan urban environment with its complex cash economy.

A few young Kikuyu formed community groups as channels for Government protection of their tribal interests. But the fundamental issue was land, and the early associations of the Kikuyu in Nairobi were revivalist meetings for the return of the ‘alienated’ highlands. About this time, a remarkable former herd-boy called Johnstone Kamau took a job reading water meters for the Municipal Council. He later changed his name to Jomo Kenyatta as he increased his involvement in the political organisation of the Kikuyu in what was to become a long and eventually traumatic struggle with the settlers.