St Margaret’s Church. It was here that the head of John Hayes was placed on display. Author’s collection

On 9 October 1926, Bertha Neilson presented her husband Arthur with a new baby daughter, whom they named Ruth. At the time, the family lived at 74 West Parade, Rhyl but a few years later, in 1933, they moved to Basingstoke in Hampshire.

In 1940, when she was fourteen years old, Ruth Neilson left school and, the following year, the family moved to Southwark, in London. Soon after this, their home was bombed in the German air-raids and the Neilsons were forced to move yet again, this time, to 19 Francis Road, Camberwell. Ruth was, by now, earning her living working at the OXO factory in Southwark but, in March 1942, she was diagnosed with rheumatic fever and spent a few months in hospital, being finally discharged, on 3 May 1942.

Ruth Neilson was not happy working at the factory, and wanted more from life. In due course she found herself a new position, as a photographer’s assistant. It was whilst working for him that one night she met a French-Canadian airman whose surname was Clare. An affair followed, Ruth found herself pregnant and, on 15 September 1944, gave birth to a son who she named Clare Andria Neilson. Unfortunately, there was no chance of a long lasting relationship with the father, as he had a wife and family back in Canada.

Ruth still hadn’t found her niche in life and other career moves followed. First, she found herself a job as a cashier in a café, but that didn’t satisfy her. Then she became a model at a camera club where she was paid the sum of £1 an hour, more than she had ever earned before. This was more Ruth’s style and she loved the glamour of the business. As part of that glamour, Ruth and her clique of friends used to spend a good deal of time at the Court Club in Duke Street and it was there that she first met the club owner, Morris Conley.

Ruth first met Conley in 1946. They hit it off from the outset and it wasn’t long before Conley offered Ruth a position as a hostess at the club, at a wage of £5 per week. More than that, there were customers to entertain and some of them were very generous indeed. They spent money freely and, since Ruth was on ten percent commission on sales, her income grew accordingly.

It was at the Court Club that Ruth Neilson first met a man who would change her name, to one of the most infamous in British criminal history. George Johnston Ellis was recently divorced. They met at a time when Ruth was somewhat fragile emotionally, as she had just undergone an abortion. A relationship developed, and the couple married on 8 November 1950.

Though the marriage was not a happy one, Ruth did get pregnant again and, on 2 October 1951, gave birth to a daughter, Georgina. Just one month later, Ruth and George split and she returned to her parents’ house, with the two children. Ruth didn’t stay there long, however. She did leave her son and her daughter with her parents, but Ruth contacted Morris Conley again. By now, the Court Club had been renamed Carroll’s but Conley was happy to take Ruth back as a hostess. Indeed, he was also happy to install Ruth in her own place, at Flat 4, Gilbert Court, Oxford Street. In fact, the only thing that seemed to have changed, was Ruth’s name. Though she had parted from her husband, Ruth would, from now on, be known to all by her new name, Ruth Ellis.

It was at Carroll’s, in 1953, that Ruth Ellis met two new men, who would play crucial roles in her life: Desmond Cussen and David Moffat Drummond Blakely. Both men were racing car enthusiasts and, at least at this stage, quite good friends. The first meeting with Blakely was anything but auspicious. He behaved in a most boorish manner and insulted some of Ruth’s fellow hostesses. Ruth gave as good as she got and told Blakely, in no uncertain terms, precisely what she thought of him.

It was in October 1953 that Morris Conley gave Ruth a new job. Now, she was promoted to manageress of another of his clubs, The Little Club, situated at 17 Brompton Road, Knightsbridge. Not only was Ruth in charge, but she was also given the flat over the club. No sooner had she taken over, than one of her first customers was David Blakely.

This time, however, his behaviour was totally different. He was charming, amusing and witty. Whereas before, Ruth had found him to be nothing more than obnoxious, now she was fascinated by him. Within a week, they were lovers. This did little to please Desmond Cussen, who was also attracted to Ruth, and the early stages of animosity between the two men, began to grow.

David Blakely, as was previously stated, was interested in motor cars and racing. With a business partner, Anthony Findlater, he was in the process of building a new racing car, which they, rather grandly, had named The Emperor. Unfortunately, building, testing, and racing the car proved to be a severe financial drain on Blakely’s resources. These financial concerns led, in turn, to temper tantrums and these meant that the new relationship with Ruth was, to say the least, volatile.

There was also the fact that, occasionally, David appeared to be ashamed of Ruth. He certainly did not believe that his parents would approve of her. On one occasion, David had driven Ruth to Penn in Buckinghamshire, where his parents lived. David called in at the local public house, only to find that his mother was already inside with some family friends. Instead of introducing his lover to his mother, David told Ruth to stay in the car and brought a drink out to her. Rather surprisingly, perhaps, Ruth did not argue and did as she was asked.

As a racing fanatic, one of the high points of the year for David Blakely was the twenty-four-hours Le Man race. In June 1954, David went to the race as a co-driver. However, he did not return to Ruth when he had said he would. This time, Ruth would not calmly accept this snub. She gained her revenge by taking Desmond Cussen to bed. When David found out about this, he was furious, but the blazing argument that ensued did not split Ruth Ellis and David Blakely. If anything, it threw them even closer together and they soon patched up the argument, in bed.

Meanwhile, Morris Conley had noticed that the takings at The Little Club, were falling. This might well have been due to the fact that Ruth’s mind was more on Blakely, than business, but Morris was not to be cajoled. In October 1954, he fired Ruth, which meant that she also lost the flat above the club. Desmond Cussen suggested that she move in with him at Goodwood Court, Devonshire Street. This led, once again, to a massive row between her and David.

Ruth lived with Desmond until February 1955, which put an extreme strain on her continuing relationship with David. After much discussion about their future, David suggested that they should get a place together. This was precisely what Ruth had wanted all along and she was deliriously happy, when she and David moved into a flat together, at 44 Egerton Gardens. Ruth and David took the lease as Mr and Mrs Ellis.

It might well be said that Ruth and David could not live apart, but equally, they could not live together. Even though they were now living in the same flat, the relationship was as tempestuous as ever. One moment they were at each other’s throats, the next they would be making love. Things were, however, moving towards some sort of crisis. That crisis came in April 1955.

On Saturday 2 April 1955, David Blakely entered The Emperor into a car race. Unfortunately, the vehicle blew up during the race. David’s already frayed temper was not helped by Ruth trying to console him. He turned on her, shouted that she was some kind of jinx, and blamed her for the problems with the car. Ruth was rather fragile emotionally as she had only recently discovered that she was pregnant once again. Back at the flat, the couple argued yet again. So heated did this argument become that, at one stage, David struck out at Ruth and hit her in the stomach. Ruth lost her baby and was unwell until Tuesday 5 April.

David’s racing partner, Anthony Findlater, lived at 29 Tanza Road, Hampstead, with his wife, Carole. Before the Findlaters had married, David had known Carole and the two had been lovers. Ruth knew about this and the knowledge that David and Carole had once been together, did not improve her state of mind that April.

On Friday 8 April, which happened to be Good Friday, David had been out with the Findlaters, drinking at the Magdala Tavern on South Hill Park. That evening, David had agreed to call for Ruth but, as he drank with his friends and brooded on the way his relationship with Ruth had been of late, David changed his mind. He simply couldn’t face Ruth that night and told Carole that he wished he had the courage to make the final break from her. Concerned that their friend had nowhere else to go, the Findlaters suggested that David spend that Easter weekend with them, in Tanza Road. A relieved David readily accepted the offer. However, he did not bother to let Ruth know of his change of plans.

At 8.30 pm that evening, a worried Ruth telephoned the Findlaters. The telephone was picked up by Anthony. Ruth said that she was very worried. David was supposed to be home by now and he hadn’t even telephoned her. When she asked Anthony if David were at Tanza Road, he denied it. Ruth did not believe him, so her next telephone call was to Desmond Cussen, who she asked to drive her from Egerton Gardens to the Findlater’s flat.

Cussen agreed to the request and, when Ruth arrived at Tanza Road, she saw David’s station wagon parked outside the flat. Now she knew the truth. David was with the Findlaters, they had lied to her and perhaps there was something after all in her suspicions that the relationship with Carole wasn’t really over after all.

Ruth rang the doorbell but there was no reply. Finding a telephone box, she then rang the Findlater’s flat again but as soon as they recognised her voice, they hung up on her. A furious Ruth returned to Desmond Cussen’s car, took his rubber coated torch, returned to David’s car and pushed in some of the windows. The police were called and they strongly advised Ruth to go home. She did, but not until 2.00 am.

After catching up on some long overdue sleep, Ruth telephoned the Findlaters again on the morning of Saturday 9 April. Once again, the receiver was replaced once her voice was recognised. Later that same day, Desmond Cussen drove Ruth back to Tanza Road and she then spent some hours, a little further down the street, watching the flat. That evening, Ruth saw that there was a party going on at the flat. Then, at around 10.00 pm, she finally saw David emerge, with an attractive woman on his arm. A distraught Ruth made her lonely way home.

Ruth spent much of Sunday 10 April, brooding on what had happened over the last few days. Meanwhile, back at Tanza Road, Carole Findlater had run out of cigarettes. It was David who volunteered to get some from the Magdala Tavern. A friend of his, Bertram Clive Gunnell, who preferred to use his middle name, said that he would accompany David down there, and perhaps they might have a drink whilst they were there. The two men left together at around 8.30 pm.

Approximately one hour later, at 9.30 pm, David and Clive left the public house. Clive walked to the front passenger seat whilst David fumbled for his car keys and strode around to the driver’s side, carrying some bottles of beer. As David rummaged through his pockets, a blonde woman stepped forward and spoke his name.

It is almost certain that David Blakely knew that the woman who had called him, was Ruth, but he chose to ignore her. He didn’t notice as Ruth reached into her handbag and brought out a .38 Smith and Wesson revolver, calling his name once more as she did so.

This time, David did react. He turned to face Ruth and, for the first time, noticed the gun in her hand. As he dashed back and tried to run around the back of the car, Ruth fired twice into his fleeing form. David fell on the pavement, close to the newsagent’s shop, next door to the Magdala. Ruth then stood over him and fired two more shots into his body.

In all, Ruth Ellis fired six shots. One bullet missed completely, four struck David Blakely, and the final one ricocheted off the wall of the Magdala and struck Gladys Kensington Yule who was walking, with her husband. Ruth, though, knew none of this, for she was still pointing the gun at David’s prone figure, and pulling the trigger repeatedly. The click of the hammer on the empty chambers was all that could now be heard.

Having heard all the commotion outside, customers of the Magdala ran outside to see what had happened. A dazed Ruth turned to one of the customers and asked him to call the police. The man, Alan Thompson, identified himself as an off duty constable, carefully took the revolver from Ruth, and placed her under arrest.

Ruth Ellis’ trial for murder opened at the Old Bailey, on 20 June 1955, before Mr Justice Havers. Throughout the two days of the proceedings, the case for the Crown was led by Mr Christmas Humphreys, who was assisted by Mr Mervyn Griffith-Jones and Miss Jean Southwood. Ruth’s defence was led by Mr Melford Stevenson, assisted by Mr Sebag Shaw and Mr Peter Rawlinson.

The first witness was Constable Philip Banyard, who had prepared a plan of the area where the shooting had taken place. He was followed by Detective Constable Thomas Macmaken, who had photographed the body of David Blakely in the mortuary.

The first major witness was Anthony Seaton Findlater. He detailed David Blakely’s movements over that Easter weekend, and went on to admit that he had lied when Ruth telephoned and he had told her that David was not at the flat.

The next witness was Bertram Clive Gunnell, who had been with David in the Magdala Tavern and who had then witnessed the shooting outside. Gunnell had left the Magdala a few steps in front of David. As Gunnell waited at the passenger door, David, carrying a flagon of beer, walked around to the driver’s side.

After the first shot had been fired, David began running around the back of the car. He was followed by Ruth and at one stage, she had told Gunnell to get out of the way. By now, David was on the pavement, running up the hill at the side of the Magdala, but Ruth pointed the gun and fired again. David Blakely fell face down on the pavement. Ruth stood over him and fired into his back.

Constable Alan Thompson, the officer who had been enjoying a quiet off-duty drink in the Magdala, then gave details of Ruth’s arrest. Before the shooting, he had noticed a blonde haired woman looking into the bar, through the window. He thought nothing of it at the time, but later realised that it was the same woman who had fired the gun. Constable Thompson testified that, when he went outside, he saw Ruth standing with her back to the pillar between the two windows. She still had the revolver in her right hand.

Thompson was followed to the witness box by Ernest Pett, an ambulance driver, who had arrived at the scene at approximately 9.25 pm on 10 April. He noted the position of David Blakely’s body, lying face down with his feet towards the public house and his head pointing up the hill. The body was placed inside the ambulance and Clive Gunnell accompanied it to the New End Hospital.

The next witness, Dr Elizabeth Beattie, was waiting for the ambulance at the hospital. She examined Blakely, at 9.45 pm and confirmed that he was dead. The body was still warm to the touch.

Doctor Beattie was followed to the witness box by Gladys Yule, who lived at 24 Parliament Hill. Gladys explained that she and her husband were walking down towards the Magdala, when they saw two men come out of the public house and stand near a car. A blonde haired lady, who she now knew to be Ruth Ellis, spoke to one of the men, and this was followed, almost immediately, by a flash and the sound of a shot. Further shots were fired and after the last one, Gladys felt a sudden searing pain in her right thumb. She realised that she had been hit by a ricochet and had to go to the hospital, by taxi, for treatment.

Doctor John Rea was on duty at the Hampstead General Hospital when Gladys Yule arrived at around 10.00 pm. He found a penetrating wound at the base of her right thumb, and a fracture of the first metacarpal bone. The bullet causing that wound had passed entirely through Mrs Yule’s hand.

Further evidence of events at the hospital were given by Dr Albert Charles Hunt, who testified that he had examined David Blakely after he had been pronounced dead. Dr Hunt went on to detail the wounds in the body. There was an entry wound in the lower part of the back on the right hand side. Tracing the path of this bullet, Dr Hunt finally found it in the tissues of the tongue. This bullet had caused wounds to the intestines, liver, left lung, aorta and windpipe.

The second injury was above the hip-bone on the left hand side, with an exit wound very close by. This bullet had merely penetrated through the fatty tissues. There were also other wounds on the inner left forearm and beneath the left shoulder blade.

Dr Hunt was followed to the stand by Ruth’s other lover, Desmond Cussen. He began by admitting that he and Ruth had been lovers, albeit briefly, in June 1954, after the Le Mans race. He went on to say that on many occasions he had assisted Ruth in using make-up to cover bruises she had received from David, after a particularly furious argument. That brief exchange, was the limit of the questioning Cussen had to suffer and later developments might possibly suggest that other questions should have been asked.

Joan Ada Georgina Dayrell Winstanley, was the housekeeper at Egerton Gardens and she confirmed that Ruth and David had lived there together, using the surname Ellis. She was followed to the stand by three separate police witnesses.

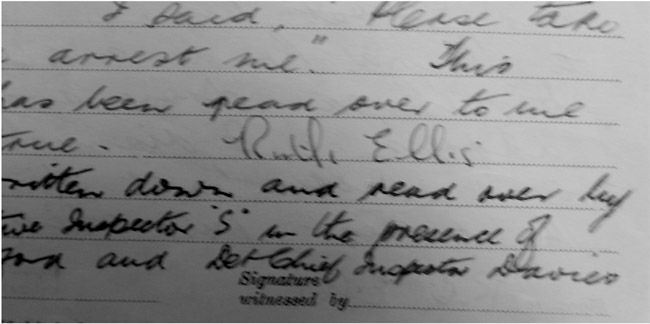

The first of these was Detective Chief Inspector Leslie Davies, who gave details of Ruth’s written statement, after she had been arrested and taken to Hampstead Police Station. This long statement included two important claims. The first was that, having decided on a course of action, Ruth had taken a revolver, which she had had in her possession for some three years. She said that she had obtained it from a customer at the club, in payment of a debt. The second claim was that she had then taken a taxi to Tanza Road

The second police witness was Detective Inspector Peter Gill, the officer who had actually written Ruth’s words down, read them back to her and then got her to sign the statement as being accurate. The final police witness was Detective Constable George Claiden, who had been present at the postmortem, carried out by Dr Hunt, on Easter Monday.

The final prosecution witness was Lewis Charles Nickolls, who gave evidence about the gun which was used to kill David Blakely. He had test fired the weapon and, comparing these bullets with those taken from the dead man, proved that the gun taken from Ruth Ellis was indeed the weapon which had caused Blakely’s injuries. Nickolls was then asked if he might give an opinion, on the distance the weapon might have been fired from. Nickolls said that he had examined Blakely’s clothing and found a bullet hole on the left shoulder at the back. The bullet used to cause this hole, and the corresponding wound on Blakley’s body, had been fired from a distance of less than three inches. This was the only bullet hole which had powder burns associated with it. In Nickolls opinion, all the other bullets had been fired from a distance.

The defence did call Ruth Ellis herself. She made no attempt to deny culpability in any way. At one stage, Mr Humphreys, for the prosecution, asked Ruth, ‘Mrs Ellis, when you fired that revolver at close range into the body of David Blakely, what did you intend to do?’ Without emotion, Ruth replied, ‘It was obvious that when I shot him, I intended to kill him.’

On the second day of the trial, the jury retired to consider its verdict at 11.52 am. After an absence of just fifteen minutes, they filed back to announce that they had found Ruth guilty of murder. She was then sentenced to death. The following day, her defence team announced that there would be no appeal. The execution date was set.

In the condemned cell at Holloway, Ruth Ellis, prisoner number 9656, wrote a number of letters. One of these, dated 12 July, was to David Blakely’s mother. It began:

Dear Mrs Cook,

No doubt these last few days have been a shock to you. Please try to believe me when I say how deeply sorry I am to have caused you this unpleasantness.

No doubt you will hear all kinds of stories regarding David and I. Please do forgive him for deceiving you. Has [sic] regarding myself, David and I have spent many happy times together.

Thursday, 7th April, David arrived home at 7.15pm. He gave me the latest photograph he had, a few days hence, had taken. He told me he had given you one Friday morning at ten o’clock he left and promised to return at eight o’clock, but never did. The two people I blame for David’s death, and my own, are the Findlaters. No doubt you will not understand this, but perhaps, before I hang, you will know what I mean. Please excuse my writing, but the pen is shocking.

I implore you to try to forgive David for living with me, but we were very much in love with one and other[sic]. Unfortunately, David was not satisfied with one woman in his life.

I have forgiven David. I only wish I could have found it in my heart to have forgiven him when he was alive.

Once again, I say I am very sorry to have caused you this misery and heartache. I shall die loving your son and you should feel content that his death has been repaid.

The letter was signed, ‘Goodbye. Ruth Ellis’

Questions still remained and Mr Victor Mishcon, Ruth’s solicitor, urged her to tell the truth, even at this late stage. No taxi driver had been found who could remember driving the distinctive blonde woman to Tanza Road, and Ruth’s story of having the gun for some three years, was also not accepted. On the same day that Ruth wrote to David’s mother, she also wrote a letter to finally reveal the truth.

This letter was written the day before Ruth Ellis was due to die. It was timed at 12.30 pm, by which time she had less than twenty-four hours to live. It began:

I, Ruth Ellis, have been advised by Mr Victor Mishcon to tell the whole truth in regard to the circumstances leading up to the killing of David Blakely. It is only with the greatest reluctance that I have decided to tell how it was that I got the gun with which I shot Blakely. I did not do so before because I felt that I was needlessly getting someone into possible trouble.

And continued:

I had been drinking Pernod (I think that is how it is spelt), in Desmond Cussen’s flat and Desmond had been drinking too. This was about 8.30 pm. We had been drinking for some time. I had been telling Desmond about Blakely’s treatment of me. I was in a terribly depressed state.

All I remember is that Desmond gave me a loaded gun. Desmond was jealous of Blakely as in fact, Blakely was of Desmond. I would say that they hated each other.

I was in such a dazed state that I cannot remember what was said. I rushed out as soon as he gave me the gun. He stayed in the flat. I rushed back in after a second or two and said, ‘Will you drive me to Hampstead?’ He did, and left me at the top of Tanza Road.

I had never seen that gun before. The only gun I had ever seen there was a small air pistol used as a game with a target.

That same day, police officers tried to find Desmond Cussen, to ask him about this confession. He was not at home and would only be traced after events had come to their conclusion. Ruth’s statement was not, of course, made public at the time, and for years afterwards, Cussen continued to deny that he had given Ruth the murder weapon, or had taken any part in the crime. Only now can the contents of Ruth’s final statement be revealed.

The following morning, Wednesday 13 July 1955, Ruth Ellis, still only twenty-eight years old, was given a tot of brandy to fortify her. She then walked calmly into the execution chamber at Holloway prison, where she was hanged, by Albert Pierrepoint. She was the last woman ever to be executed in the United Kingdom.

St Margaret’s Church. It was here that the head of John Hayes was placed on display. Author’s collection

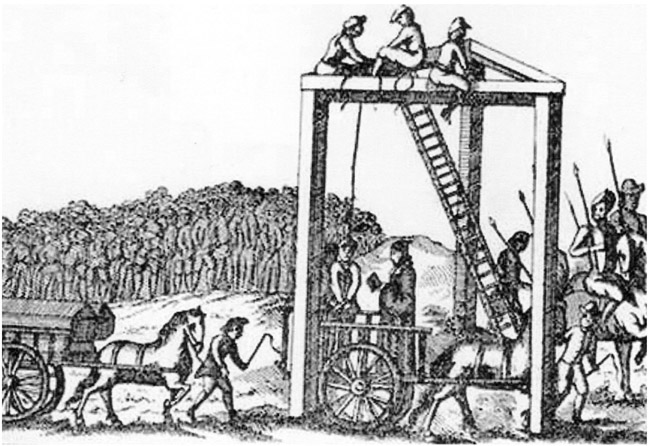

The Tyburn gallows, where Catherine Conway, Elizabeth Banks and Margaret Harvey were hanged in 1750. Author’s collection

Elizabeth Brownrigg, who cruelly murdered her servant girl. Author’s collection

An engraving of the time, showing how the Brownrigg crime was committed. Author’s collection

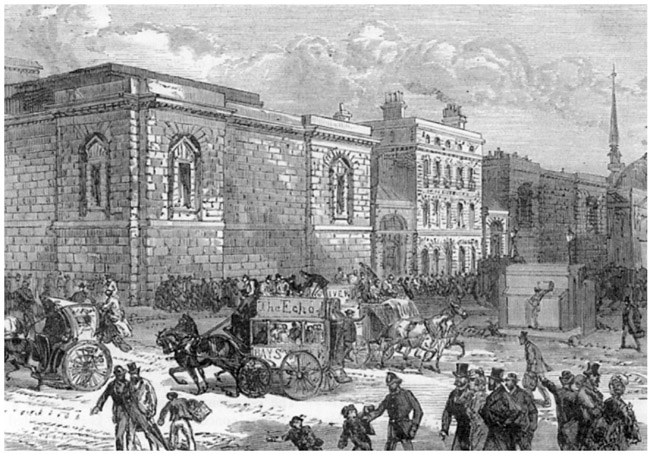

A contemporary illustration of Newgate prison, where Elizabeth Taylor was hanged. Author’s collection

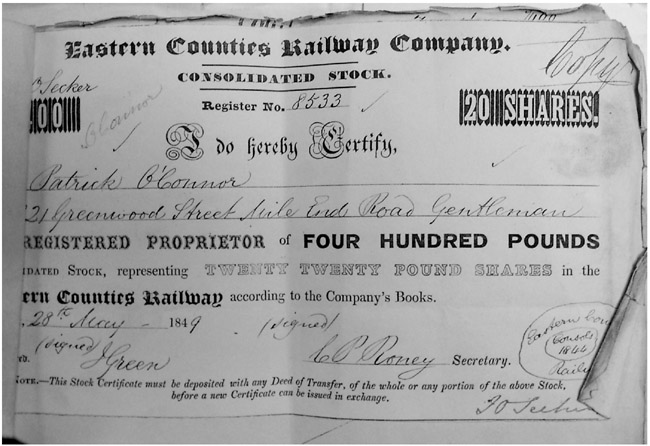

One of the share certificates stolen by the Mannings. The National Archives

Maria Manning, who plotted a murder for gain. Author’s collection

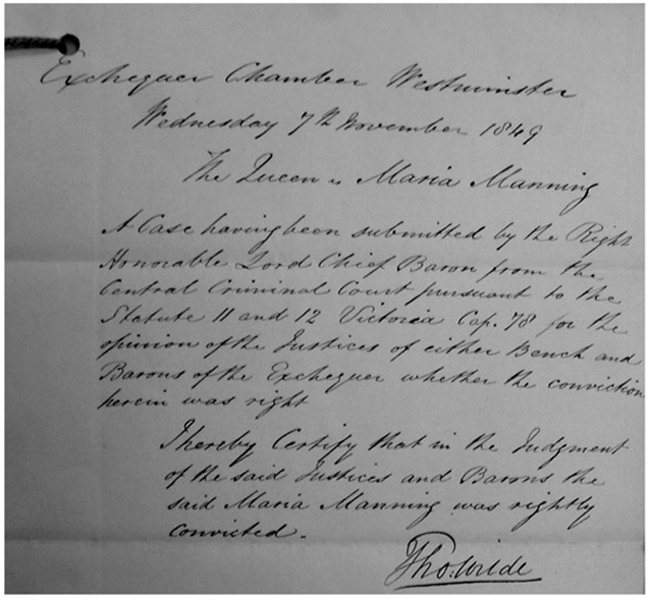

A note from the authorities stating that the death sentence on Maria Manning was ‘just’. The National Archives

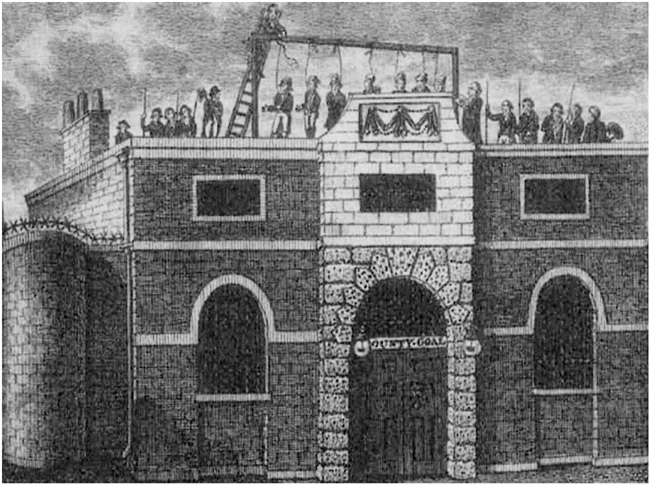

Horsemonger Lane prison, an illustration of how miscreants were hanged on the roof. Author’s collection

Florence Bravo. Did she poison her husband as some believed? Author’s collection

Charles Bravo, who died from antimony poisoning. Author’s collection

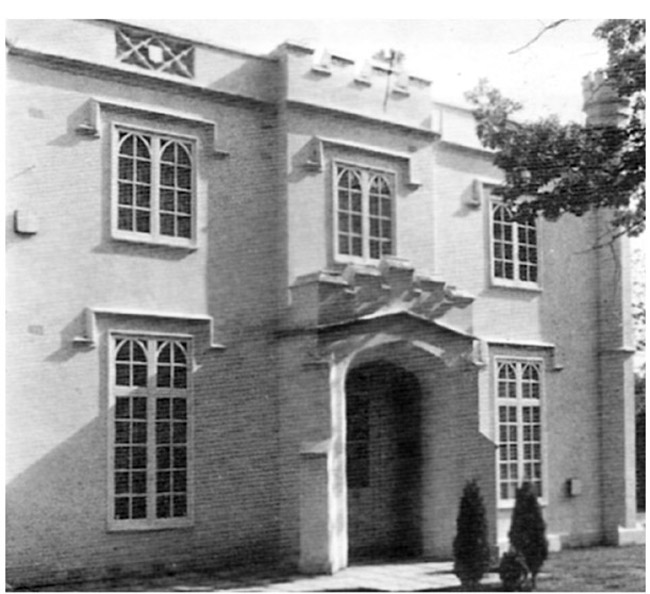

The Priory, in Balham, where Charles Bravo met his death. Author’s collection

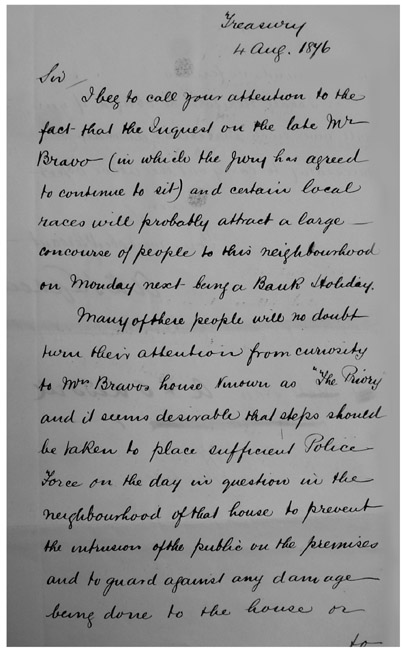

A contemporary letter from the Treasury, pointing out that crowd control might be a problem at the Bravo inquest. The National Archives

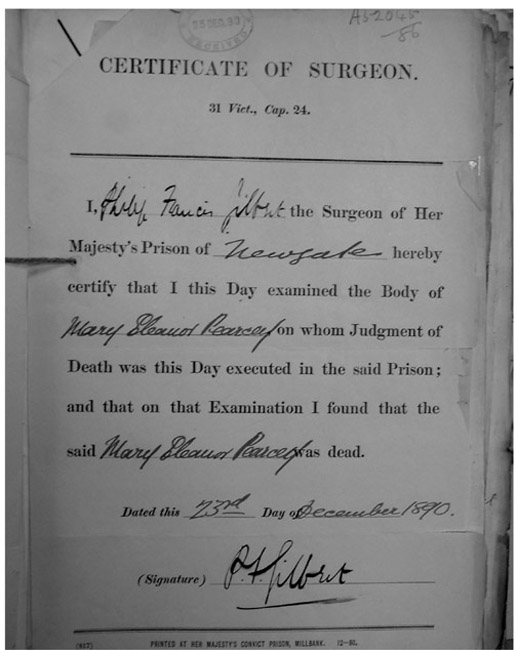

Confirmation that Mary Eleanor Pearcey had been executed. The National Archives

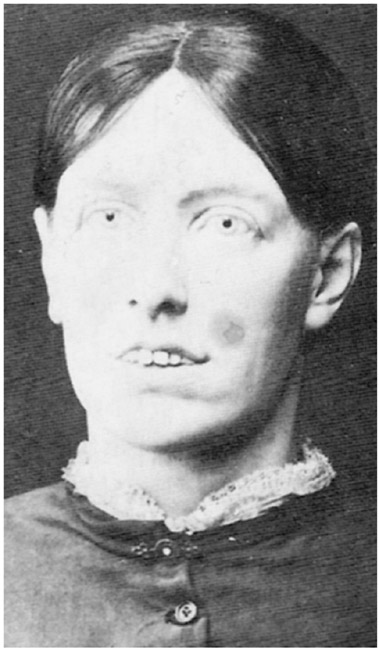

Mary Eleanor Pearcey. This waxwork of her appeared in Madame Tussauds for many years after her death. Author’s collection

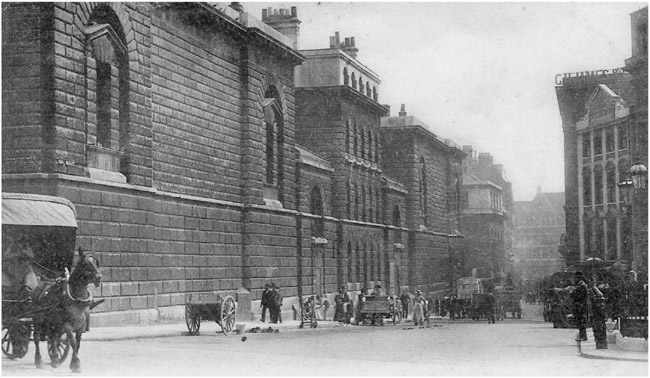

Newgate prison, where Mary Eleanor Pearcey was hanged. Author’s collection

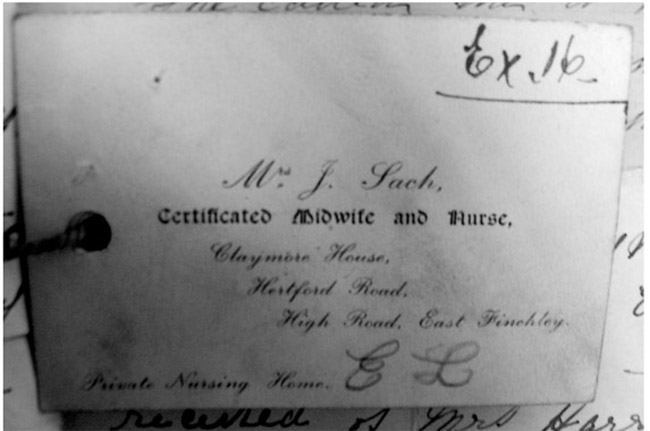

Amelia Sach’s business card. The National Archives

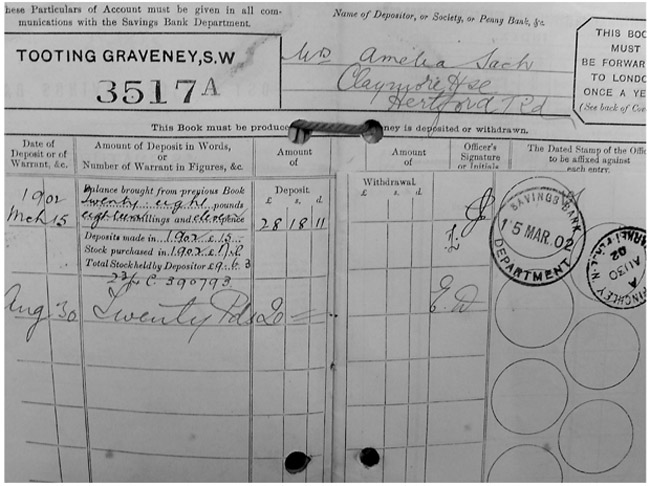

Amelia Sach’s Post Office account book. The National Archives

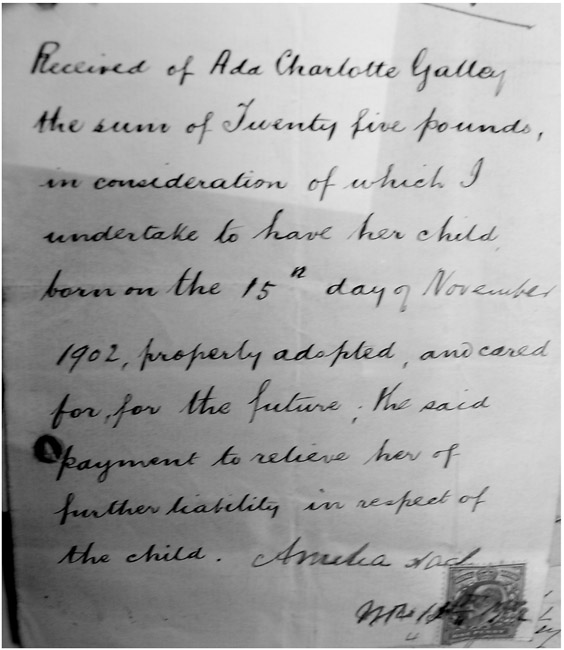

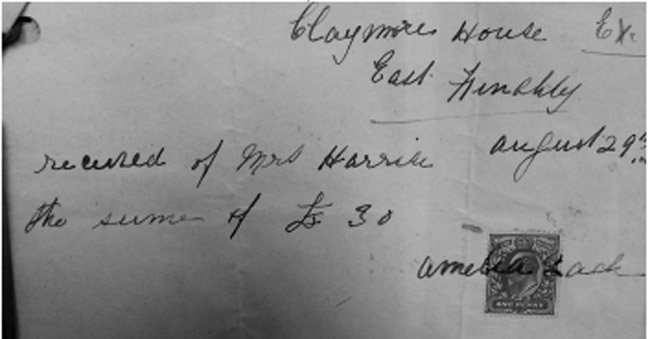

The receipt to Ada Galley, signed by Mrs Sach. The National Archives

Another receipt signed by Amelia Sach and produced as evidence at her trial. The National Archives

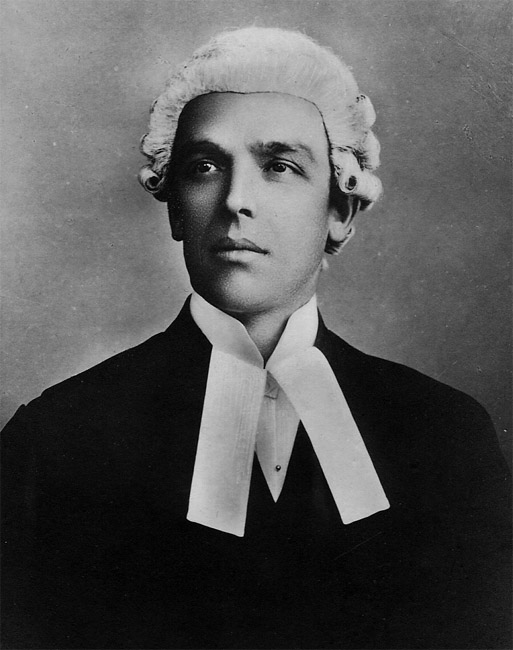

Mr Justice Darling, who sentenced Sach and Walters to death. Author’s collection

The Old Bailey, where Clara Alice White faced her trial for murder. Author’s collection

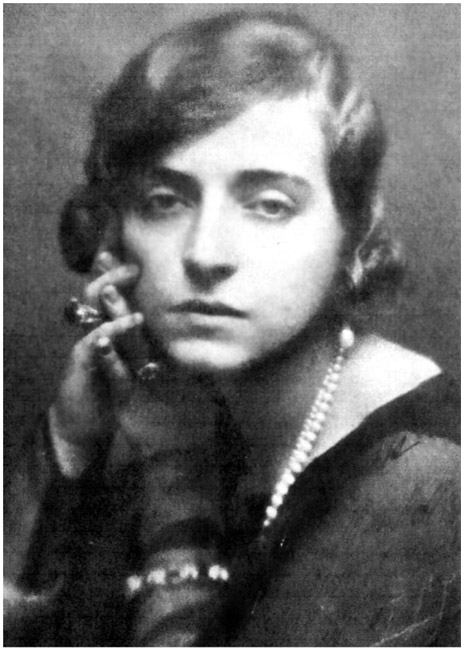

Marie Fahmy – a picture taken before her marriage. The National Archives

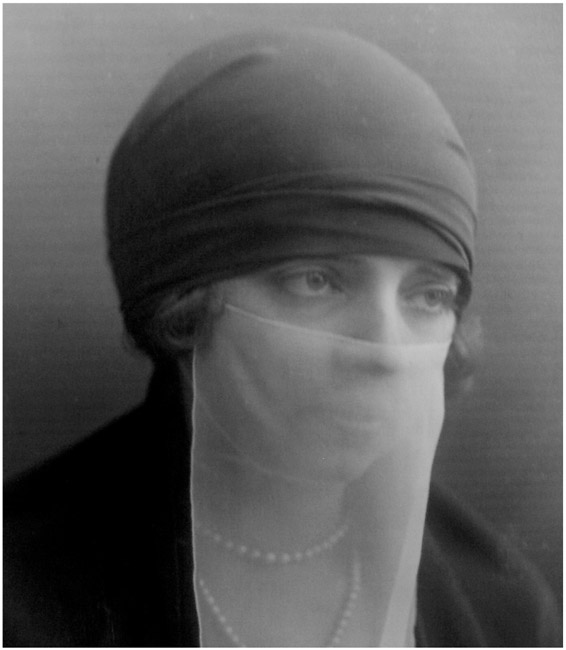

Another picture of Marie Fahamy, this time wearing the veil her husband demanded she wore in public. The National Archives

Hella Christofi, the murdered woman. Author’s collection

Styllou Christofi, the Cypriot accused of the brutal murder of her daughter-in-law. Author’s collection

The room where the original Christofi attack took place. The National Archives

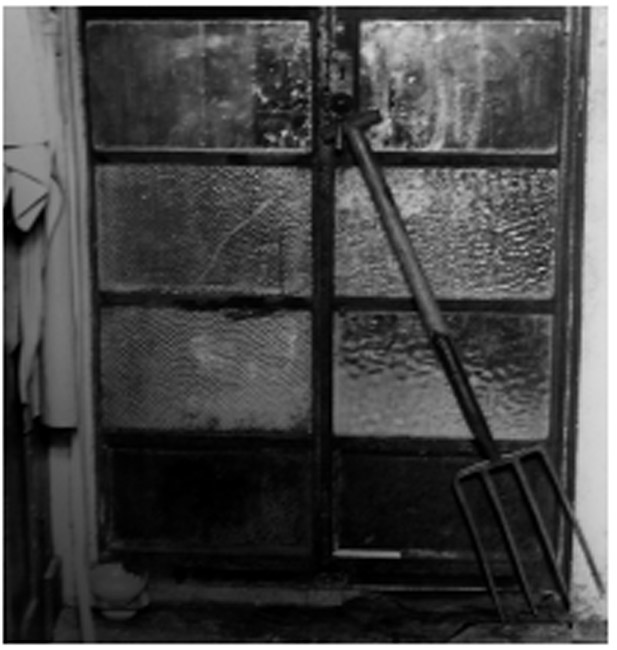

The garden fork used to secure the door to the yard at the Christofi murder house. The National Archives

Another view of the room where Hella was attacked. Her blood was found on the iron tray at the foot of the stove. The National Archives

The rear wall at the Christofi’s, which a neighbour looked over to see what he thought was a mannequin on fire. The National Archives

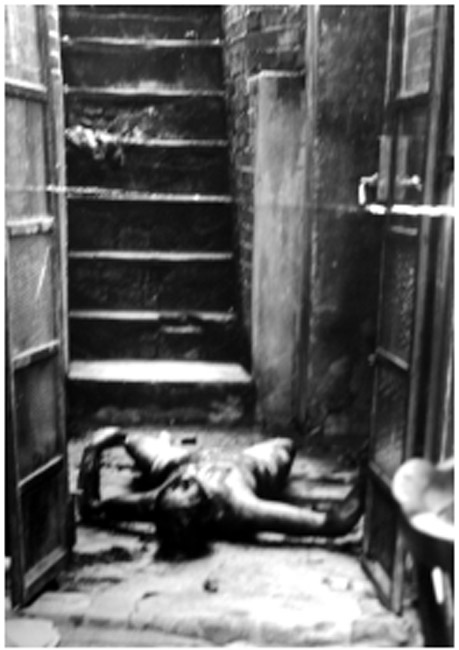

The body of Hella Christofi in situ. The National Archives

The badly burned body I of Hella Christofi. The National Archives

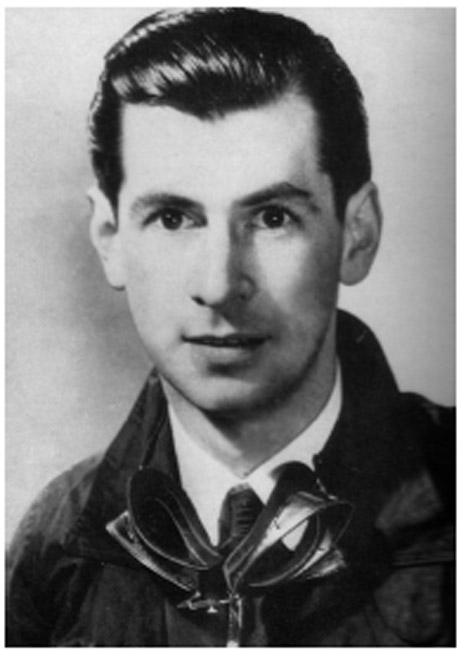

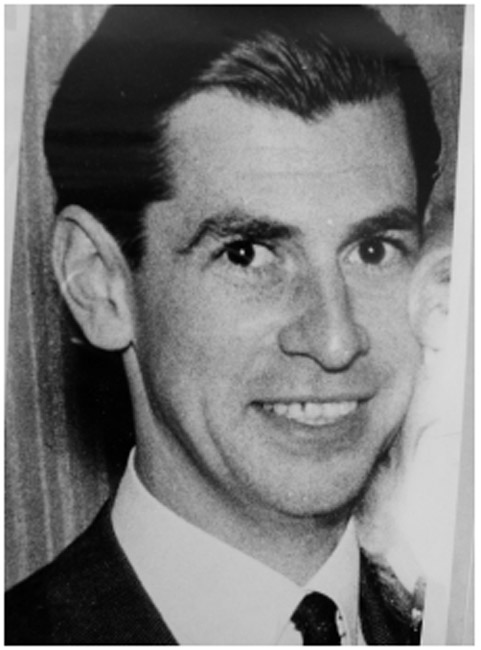

David Blakely, the man shot by Ruth Ellis. Author’s collection

Ruth Ellis, with Desmond Cussen, the man who always denied providing her with the murder weapon. Author’s collection

The Magdala Tavern. Notice the bullet holes in the wall. David Blakely died close to the newsagents next door. Author’s collection

The car which Blakely drove down to the Magdale and which he tried to run around in order to escape his assailant. The National Archives

Another picture of David Blakely. Author’s collection

David Blakely in the mortuary. The National Archives

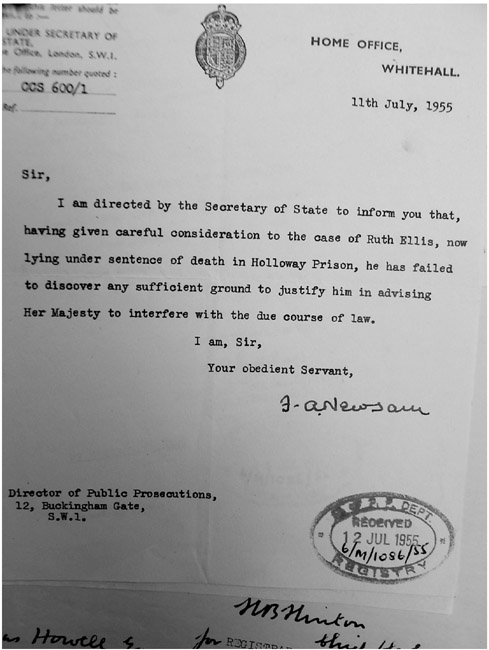

Confirmation from the Home Office that the Ruth Ellis death sentence would be carried out. The National Archives

The end of Ruth Ellis’ confession, signed by her. The National Archives