Willendorf Venus, c. 20,000 BCE, Limestone, 4 1/2 in (10.8 cm) high

Willendorf Venus, c. 20,000 BCE, Limestone, 4 1/2 in (10.8 cm) highTHE IMAGE STANDS IN FOR THE REAL THING

Representation is a convention in painting and sculpture whereby a flat image or a three-dimensional form is understood to stand in for a visual experience of something in the real world.

Translating a visual experience is central to the activity of representational art. The nature of the translation and how it affects the viewers’ perception of the subject becomes a powerful way in which expression may be achieved. Subjects may be simplified, distorted, or rebuilt in various ways. The viewers’ comparisons of their experiences of the real world with their apprehension of its representation in a work of art provides the ground for a wide variety of meaning and expression.

The origins of representational art extend back into prehistory with cave paintings and simple sculpture. With the emergence of more advanced cultures, representations became more elaborate. Egyptian art developed complex iconography based on flat designs in which humans, supernatural beings, and physical objects could be shown and manipulated. More comprehensive and naturalistic representations of the human form appear in Greek culture and reach a level of unparalleled sophistication around 400 BCE. Roman art in general pursued a taste for naturalism, particularly in sculpture. Medieval art saw a return to flatter and more linear representation, while the Renaissance ushered in an entirely more comprehensive set of tools, including perspective, to enable a much fuller representation of the world. Contemporary artists deploy a wide variety of representational approaches, from crude and primitive expressions to flawless photographic realism.

Both Aristotle and Plato discussed representation. Aristotle considered it to be natural to human beings and necessary for their comprehension of the world. Plato, on the other hand, asserted that representation involves the creation of illusions that may or may not say truthful things about the world. As such, representations have the capacity to lead the viewer astray. The potential deceptiveness of representation and its ability to mold perception has emerged as a perennial issue in the modern world. Advertising, propaganda, and the fine arts are areas in which both visual and verbal representations are manipulated to shift the perception and understanding of the viewer.

See also: Realism on page 148

Willendorf Venus, c. 20,000 BCE, Limestone, 4 1/2 in (10.8 cm) high

Willendorf Venus, c. 20,000 BCE, Limestone, 4 1/2 in (10.8 cm) high

One of the earliest surviving artworks, the Willendorf Venus may have had a role as a ritualistic symbol of fertility.

Photo: Don Hitchcock

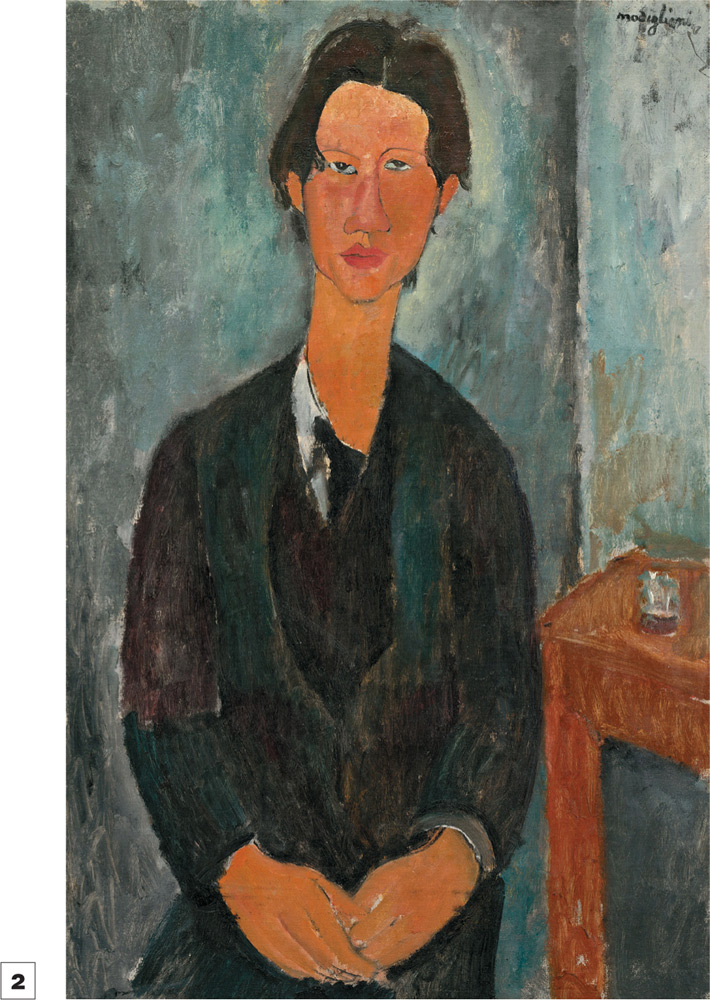

Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920)

Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920)

Chaim Soutine, 1917, Oil on canvas, 36 1/8 × 23 1/2 in (91.7 × 59.7 cm)

Modigliani deploys the new visual language pioneered by Cubism. He dispenses with perspective and rendered form using instead a flattened space and stylized outline.

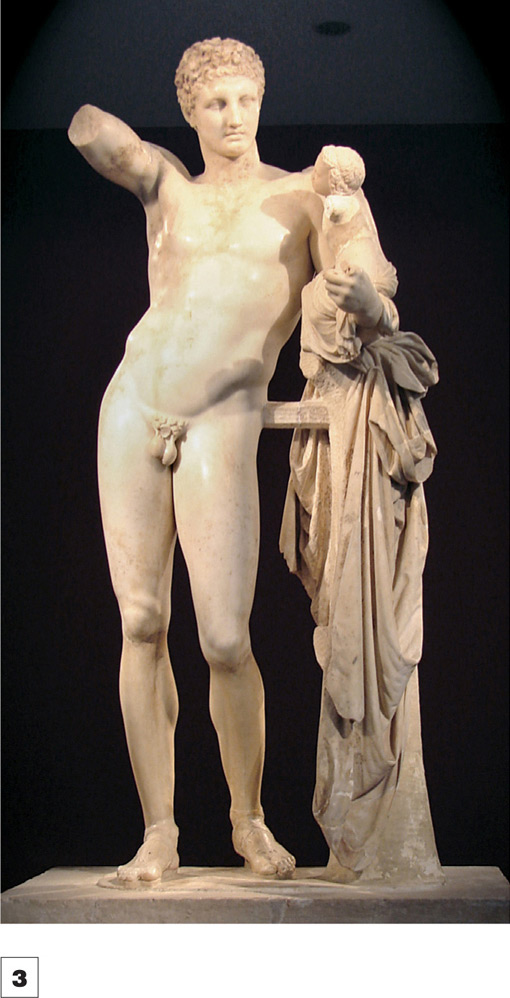

Praxiteles

Praxiteles

Hermes Carrying the Infant Dionysius, 4th century BCE, Marble, 7 1/2 ft (2.1 m) high

The Greek sculptor’s comprehension of the nuance and complexity of the human form remains a high point in representational art.

Raphael (1483–1520)

Raphael (1483–1520)

The School of Athens, 1509, Fresco, 16 ft 5 in × 25 ft 3 in (5 × 7.7 m), Apostolic Palace, Vatican City

By 1500, artists had mastered both perspective and elaborate rendering of three-dimensional form, enabling extremely comprehensive representations of the visible world.