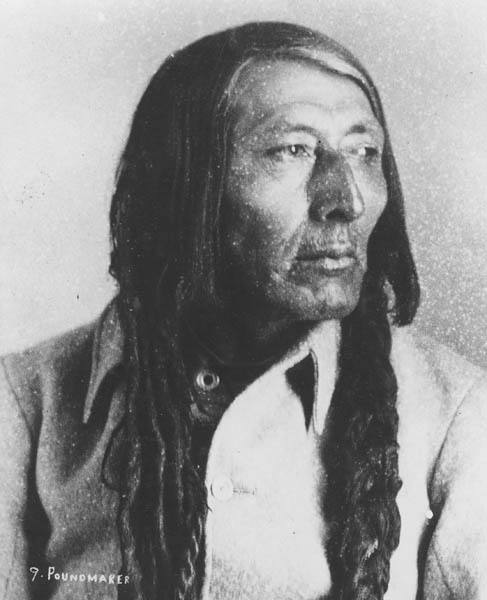

Poundmaker

Glenbow Archives (NA-1681-4)

CHAPTER

3

In the tradition of the plains First Nations, it was not unusual for a young person to be adopted by the chief of another band. The custom was often used to create alliances between bands. But when Crowfoot, the famous Blackfoot chief, adopted a young Cree man named Poundmaker, he astonished two entire nations.

Poundmaker knew tragedy early in his life, but the experience taught him about generosity and caring for the needy. He was a quiet and thoughtful person and a good hunter, even as a boy. He was also musical, adept at drumming and storytelling. He was gentle with children, courteous and respectful with elders. Slender with waist-length hair, he had a commanding physical presence, standing more than 6 feet 6 inches tall. As a young man, Poundmaker was known as a fierce warrior. Later in life, he became an astute politician and exceptional speaker.

The Orphan

Poundmaker was born around 1840, in the Fort Carlton area north of present-day Saskatoon. His mother was Cree, but may have had French blood too. His father was a Stoney who lived among the Plains Cree. He was greatly esteemed as a buffalo caller—someone with skill in attracting and luring buffalo into the rough corrals or “pounds” constructed to confuse and trap them. The buffalo caller was known as Pitikwahanapiwiyin (poundmaker), a name he also gave to his son.

Poundmaker had an older brother, Yellow Mud Blanket, and a younger sister. Their father died when the children were young, so their mother returned to her parents. Within a few years, their mother and both grandparents also died, leaving the children homeless. A generous family took in the three orphans. Yellow Mud Blanket and Poundmaker worked hard to hunt and help provide enough meat for their adopted family.

Like other young men of his band, Poundmaker spent his youth as a free-roaming warrior, stealing horses and raiding enemies. He married young and gave up his fighting ways to raise a family. Soon he also married his wife’s sister, a common practice. Poundmaker settled into a happy life of hunting, and he became a councillor to Red Pheasant, chief of his band. Then a remarkable event changed Poundmaker’s life.

Although the Cree and Blackfoot were bitter enemies, there was talk of peace between the nations. In fact, the famous Blackfoot leader, Crowfoot, had personally come to Red Pheasant’s band to bring gifts of tobacco and to talk of peace. While they were camped among the Cree, Crowfoot’s wife noticed a tall young man who alarmed her greatly. He looked almost exactly like the son she and Crowfoot had recently lost, killed by a Cree war party. She called Crowfoot to meet the young man. Crowfoot, too, was stunned by Poundmaker’s appearance.

To the amazement of everyone in Red Pheasant’s band, Crowfoot invited Poundmaker to return with him to his Blackfoot camp. Poundmaker accepted and rode with the Blackfoot leader across the plains to the Oldman River. When Poundmaker became an honoured guest in Crowfoot’s lodge, the young men of Crowfoot’s band were angry and resentful. They plotted revenge against Poundmaker, thinking they could lure him away from his protector and swiftly murder him. But they feared Crowfoot’s wrath, even more so when their chief announced that he had adopted Poundmaker as his son. Crowfoot gave Poundmaker a Blackfoot name, Wolf Thin Legs, and thus began a close and loving relationship that lasted until Poundmaker’s death many years later.

Poundmaker spent the winter of 1873–74 in the camp of his adoptive father. He then returned to his own people, who lived to the northeast. He brought many presents, including several horses, to prove that Crowfoot had indeed adopted him. He also carried a message of peace. Crowfoot still wanted to put an end to the bloody raids and horse stealing between the two nations. He realized the Blackfoot, Cree and other First Nations would have to unite to make their voices heard.

Poundmaker himself agreed with this assessment, but he knew it would be difficult to convince the Cree to give up their old fighting ways. Poundmaker’s status and reputation among the Cree was greatly enhanced by his close relationship with Crowfoot. Here was a man who had spent the entire winter in the lodge of his people’s arch-enemy and not only survived, he came back with gifts and bore a strange message: peace between the nations. Poundmaker visited many Cree camps on his way back to his own band. He countered distrust and suspicion with steady nerves, cool-headed judgment and persuasive arguments.

His association with Crowfoot, combined with his eloquence and leadership, brought even more status for Poundmaker. Though still a young man, he became a Cree chief shortly after his return from Crowfoot’s camp.

A New Life

On August 18, 1876, Lieutenant-Governor Alexander Morris sat before a council of Cree chiefs who had gathered at Fort Carlton to sign a treaty with the Dominion government. Morris had spent the previous day explaining the treaty in terms simple enough to be easily translated. Now it was their turn to respond to his offers. Morris considered the treaty to be generous—the government would give a section of land (one square mile) for every family, and in addition would build schools and supply farm implements, seed and livestock. Yet when the strikingly tall man named Poundmaker rose to speak, the Cree man was angry. “The governor mentions how much land is given to us. He says 640 acres for each family, he will give us. This is our land! It isn’t a piece of pemmican to be cut off and given in little pieces back to us. It is ours and we will take what we want.”

Poundmaker went on. “I beg of you to assist me in every way possible. When I am at a loss how to proceed I want the advice and assistance of the government. The children yet unborn, I wish you to treat them in like manner as they advance in civilization like the white man.”

It was a classic case of underestimation on one side, misunderstanding on the other. Morris had no authority to alter the treaty or offer more than he had already stated. The Cree were there to negotiate, not to simply accept the treaty without question. They did not realize that Morris had already put all his cards on the table; he had nothing more to offer them. He certainly could not promise what Poundmaker was requesting. Morris hedged and offered to give the Cree such assistance as would be required in the event of a disaster. Though Poundmaker remained reluctant, with this reassurance in place, he and the other Cree chiefs signed the treaty and Morris went on to Fort Pitt.

The next three years were difficult for Poundmaker and all the Cree people. Despite signing Treaty Six, Poundmaker did not take a reserve right away. He and his band continued to follow the buffalo. But the buffalo were disappearing more quickly than anyone would have believed. Finally, with the herds diminished and his people starving, Poundmaker ushered his band south into Montana to find food. They remained south of the border until 1879, when a skirmish with the American cavalry convinced Poundmaker to return to Canada. He journeyed north and took a reserve on the Battle River, close to the tiny settlement of Battleford.

Here, he and his people resigned themselves to learning a new life. Seeing that their only salvation would be to give up their old ways, Poundmaker tried to set an example for his band by working hard to grow crops and erect fences for cattle. The band still depended on government rations, but they were making an effort to become self-sufficient farmers. In the spring of 1880, as promised in the treaty, livestock, seed and farm implements were brought to Poundmaker’s reserve.

With members of his band looking on, he hitched a team of oxen and prepared to plough some land for seeding. The farm instructor advised Poundmaker to find one or two stout men to add their weight to the plough’s crossbeam because the virgin prairie would resist the blade. Poundmaker’s friend Mustatamus volunteered. Poundmaker commanded the oxen to move forward. Nothing happened. Exasperated, the chief called for someone to get the team moving. Eager to comply, two men jumped up and began whooping and yelling. The startled oxen jumped forward. The plough blade struck an unseen rock, throwing Poundmaker and Mustatamus backward, while the ox team, now totally terrified, took off across the field. To much laughter, the team was captured and several more Cree men came forward to help. Time and again the plough jammed against rocks and roots, but Poundmaker was determined. The onlookers laughed and cheered—and the field, at last, was ploughed and ready for planting.

The men of Poundmaker’s band went hunting while the crops grew. They caught anything they could—rabbits, deer, prairie chickens—and kept alert for signs of buffalo. But the huge herds were gone, never to return. The people preserved what meat they could, harvested grain and root crops in the fall and scraped though the winter.

The Letter and the Battle

In the early spring of 1885, the situation on Poundmaker’s reserve became one of unrest. The band was divided. Poundmaker continued working hard to learn farming. But no matter how hard he tried to adopt a new way of life, he could not keep hunger from stalking his people. They were still receiving daily rations, yet the people were continually on the brink of starvation. Like the young men of Big Bear’s camp, the young men on Poundmaker’s reserve did not like farming. They did not want to give up the old ways. They were restless and angry and ready for a fight.

In March, news of the Métis rebellion came to Battleford, and the settlers there became nervous. With seven Cree reserves in the area, would Battleford be the next location of an uprising? The settlers learned of the massacre at Frog Lake and the burning of Fort Pitt. Tension filled the air like dust. So when Poundmaker sent a message that he and two other chiefs were on their way to Battleford to speak with Indian agent John Rae, the townspeople and the surrounding farmers feared the worst. Some 500 people barricaded themselves inside the mounted police post and warily awaited Poundmaker’s arrival.

On the morning of March 30, Poundmaker came to Battleford. He wanted to speak with Rae, first to reassure him that his band had no intention of joining the rebellion, and then to press Rae for more farm implements, seed and rations. Poundmaker was there to plead for better conditions for his people, no doubt aware that the Riel Rebellion had handed the Cree a perfect opportunity to use the settlers’ fear of a Native uprising as a bargaining position. The streets were deserted as the Cree leader and his supporters rode into town. Eventually they came to the police barracks and asked to speak with Rae, but the distrustful agent would not show himself, nor would he send the tea and tobacco that Poundmaker requested as a sign of good faith. Poundmaker waited patiently, but by day’s end Rae had done nothing.

And so it was that Poundmaker found himself in an empty, undefended town with roving Cree warriors who were barely under his control. Finally, as darkness fell, the inevitable happened. The Cree fighters, who were hungry and dressed in rags, began looting the stores and houses, eating and drinking all night. Poundmaker tried to stop the pillaging and destruction, but the ball was rolling beyond his control. He left Battleford in disgust. By morning, the young men followed him, leaving the town ransacked and ruined.

In the police post, the settlers and townsfolk could hear the revelry and laughter outside. They telegraphed a desperate plea for help. In Swift Current, far to the south, General Frederick Middleton was leading the Canadian army in a march northward to do battle with Riel and the Métis. Upon receiving news of the siege at Battleford, Middleton dispatched Lieutenant-Colonel W.D. Otter and his troops to proceed immediately to Battleford and restore order.

For many days after their initial spree, Cree warriors kept returning to the town to replenish their supplies of food, drink and ammunition. They burned several stores and houses. Yet, according to Robert Jefferson, the area’s farm instructor (who was married to Poundmaker’s sister), the Cree only wanted to speak to agent Rae and negotiate with him. Jefferson, who remained in the Cree camp throughout the troubles in Battleford, later wrote that the Cree warriors never mounted an organized attack on Battleford. They simply took advantage of the situation to get food, blankets and whisky.

Meanwhile, Métis leader Louis Riel was in trouble. His fighters were vastly outnumbered by Middleton and the Canadian troops. He needed reinforcements. He needed the Cree.

Two days after the siege of Battleford started, Métis messengers visited Poundmaker’s camp, telling tales of courage and great deeds, leading the young Cree warriors to believe that Riel had the upper hand. The Cree would realize their ambitions if only they would join Riel’s forces. In fact, the opposite was true. Poundmaker wisely saw through the messengers’ rhetoric.

Like Big Bear far to the northeast, Poundmaker was no longer in control of his band. The warrior society, full of headstrong young fighters, was running the camp now. A Métis messenger named Joseph Jobin rode into the camp and taunted the warriors. Jobin suggested the Cree war society should send a letter to Riel, telling him that they would come. Robert Jefferson was summoned to write the letter. Poundmaker stepped inside the lodge but sat quietly, taking no part in the discussion or the letter that Jobin dictated. Jobin told Jefferson to write that the Cree were anxious to join Riel and would be no more than four days on the trail. Jobin added a number of wild stories, including a claim that the Cree intended to take Battleford. Then Jobin told Jefferson to write Poundmaker’s name at the bottom of the letter.

On April 24, Lieutenant-Colonel Otter and almost 500 troops arrived in Battleford to the thankful cheers of the relieved residents who had been holed up in their crowded fort for more than three weeks. Otter had no authority to pursue the Cree—he was simply to keep the peace in Battleford—but he took matters into his own hands and set out to find and punish Poundmaker. Otter and 325 soldiers began their march.

The next day, May 2, 1885, Otter drew near the Cree camp. He thought he would surprise the Cree with an attack at dawn, but the Cree knew exactly what was going on and moved to the west side of Cut Knife Hill, a long, gentle slope that was scored by a series of deep ravines. As the soldiers crossed the creek and approached the slope, Cree warriors were waiting in the ravines, hidden by bush. The troops noticed some of these snipers and opened fire. The army was completely exposed on the slope’s open ground. Receiving fire on all sides from an enemy they could not see, the soldiers believed they were greatly outnumbered, but actually there were only 50 Cree fighters.

The Cree gradually moved around behind the soldiers. The troops were almost surrounded when Otter realized what was happening. He ordered a hasty retreat. The soldiers ran down the hill in disarray and panic. Mounted Cree warriors were ready to follow, but Poundmaker stepped forward saying, “They have come here to fight us and we have fought them. Now let them go.”

Two days later, Jobin returned with more news from Riel and another request to send fighters. Poundmaker was furious. In the midst of a council meeting, he called Jobin a liar and blamed the Métis for the trouble at Battleford and the resulting battle at Cut Knife Hill. He told the assembly that he intended to take his family to seek sanctuary in the hills. But the Cree warriors, fuelled by their rout of Otter and his troops, chose to join Riel. With threats, armed Métis fighters forced Poundmaker and his followers to travel eastward to where Riel was waiting. Throughout this journey, though a virtual prisoner himself, Poundmaker took great care to ensure the safety of Jefferson, the missionary Father Cochin and several other hostages.

When they were in the Eagle Hills, about 100 kilometres south of Battleford, the Cree learned the Canadian army had crushed the rebellion and Riel was under arrest. What would the Cree warriors do now? Would they continue their own fight? Would they run for the US border? Would they surrender? A council was called. One by one, each man stood to give his opinion. At last, it was Poundmaker’s turn.

Poundmaker tried to make the angry ones see reason. He said, “Today, it is no more a question of fighting. You who have committed murders, who have plundered the innocents, it is no more time to think of saving your own lives. Look at all these women and children. Look at all these youths around you. They are all clamouring for their lives. It is a case of saving them. I know we are all brave. If we keep on fighting the whites, we can embarrass them. But we will be overcome by their numbers, and nothing tells us that our children will survive. I would sooner give myself up and run the risk of being hanged than see my tribe and children shot through my fault, and by an unreasonable resistance see streams of blood. Now, let everyone who has a heart do as I do and follow me.”

The council agreed.

Poundmaker asked his brother-in-law, Robert Jefferson, to write a letter to General Middleton, asking for various terms and conditions of the Cree’s surrender. Jefferson rode away and delivered the letter, but Middleton exploded into a sputtering rage and denied that any terms would be extended to Poundmaker. It would be unconditional surrender or war. Jefferson returned to Poundmaker with this news. With a heavy heart, the Cree leader took his people north to Battleford to lay down their arms.

A dignified leader, a man of peace, Poundmaker faced Middleton. He first gave the general his rifle, then extended his hand in a sign of friendship. Middleton haughtily spurned the outstretched hand. Instead, he had Poundmaker arrested and put into chains.

The Trial

On July 4, 1885, Poundmaker and several other Native leaders were sent to Regina for trial. Charged with felony treason, he pleaded not guilty. He was defended by Beverley Robertson. Six witnesses spoke in his defence versus nine for the prosecution. One of the prosecutor’s witnesses was none other than Robert Jefferson, Poundmaker’s brother-in-law.

The Crown prosecutor, David Scott, opened his arguments by presenting the damning letter to Riel, written on April 29 at Cut Knife Hill and apparently signed by Poundmaker. Then Jefferson took the witness stand. Under questioning, he related to the jury how he had written the letter to Riel exactly as Jobin had told him to. But Jefferson’s testimony became uncertain when he was asked whether Poundmaker himself took any part in dictating the letter. To further cloud his own evidence, Jefferson revealed that another Cree warrior told him to affix Poundmaker’s name to the letter—and after all the chiefs had signed, the Métis appeared to have made changes to the text. The letter, which at first seemed to be strong evidence against Poundmaker, was shown to be the flimsy collection of lies that it was. Scott moved on, calling NWMP superintendent William Herchmer to the stand.

Herchmer testified that he had seen Poundmaker twice during the battle, once from at least 1,500 metres, the second time from some three kilometres away. Herchmer told the jury he could not be certain what Poundmaker was doing, but ventured the opinion that the Cree leader was giving directions to the warriors. Scott also brought forth evidence about Poundmaker’s supposed part in the siege of Battleford.

For his defence, Robertson tried to make the jury understand the inner workings of Cree society, and that the chief or leader usually gives up his authority to a war chief in times of battle. He tried to show that Poundmaker was not in control of the band. Neither did he make decisions about whether or not to join Riel, to loot and burn Battleford, or to fight Otter and the Canadian army at Cut Knife Hill. Robertson also tried to establish Poundmaker as a man of peace and reason, using several witnesses who knew the chief well and could vouch for his character.

It was all in vain. After only a few minutes of deliberation, the jury pronounced Poundmaker guilty. The judge then allowed Poundmaker to speak. He said, “I am not guilty. Much has been said against me that is not true. Everything I could do was done to prevent bloodshed. Had I wanted war, I would not be here now; I would be on the prairie. You did not catch me; I gave myself up. You have got me because I wanted peace.”

Prison and Freedom

Poundmaker was sentenced to three years in the Stony Mountain Penitentiary in Winnipeg. His health deteriorated from the beginning of his imprisonment. After only nine months, his state of health was so alarming that the Canadian government pardoned him and he was released. He went back to his reserve near Battleford to find his people broken in body and spirit. Poundmaker had no authority. Though his people welcomed him home, the government would not allow him to resume his position as chief. Disheartened, Poundmaker decided to visit Crowfoot. He left his family and his band on May 7, 1886. They never saw him again.

Accompanied by Stony Woman, his third wife, Poundmaker walked across the plains. The weather was cool and rainy. By the time he reached Blackfoot Crossing and Crowfoot’s reserve, Poundmaker was ill and weak. Crowfoot and his band were as destitute as any of the plains peoples, but the Blackfoot leader welcomed his old friend and adopted son. Poundmaker recovered his strength over the next few weeks, and the two men spent much time talking and smoking.

It was early summer. The Blackfoot people were gathered for their annual Sun Dance. There are many stories about what happened on July 4, in the midst of the celebrations. One story alleges that Poundmaker collapsed while dancing. Another claims he and Crowfoot were taking a ceremonial meal together when Poundmaker began to cough violently. Still another declares Poundmaker was making a speech to a group of Blackfoot when he suddenly fell to the ground, unconscious. All the stories agree Poundmaker died within a few minutes of the first sign of trouble. The accepted theory is that a blood vessel burst in his weakened lungs and he died of severe blood loss before the horrified eyes of his loving stepfather, Crowfoot. Poundmaker was just 44.

He was buried at Blackfoot Crossing on a slope overlooking the Bow River. Crowfoot died only a few years later and was buried at this spot too. But the Cree people wanted the bones of their chief and leader returned to them. In 1967, they moved Poundmaker and buried him again—on the long, gentle slope of Cut Knife Hill.

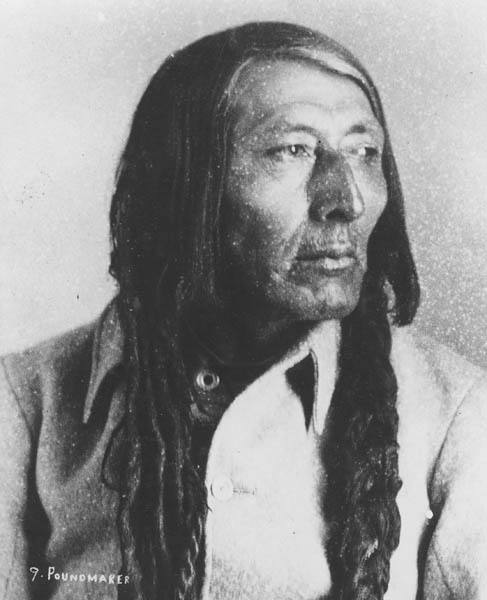

Poundmaker

Glenbow Archives (NA-1681-4)