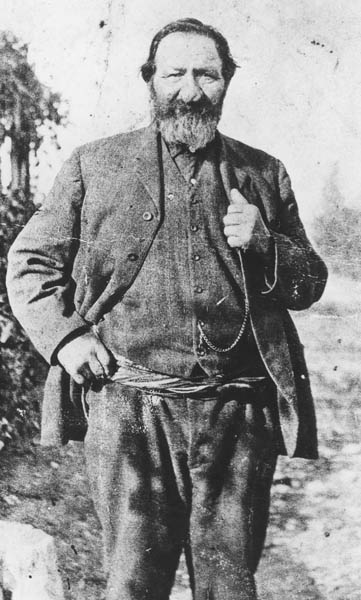

Peter Erasmus

Glenbow Archives (NA-3148-1)

CHAPTER

4

During his life, the remarkable Peter Erasmus was employed by Methodist missionaries as a teacher, translator, hunter and guide. He was an interpreter and guide for the famous Palliser Expedition. He made a tidy sum of money in gold mining, then lost it all to unfortunate investments.

Peter lived for awhile among the Cree at Whitefish Lake. As well as Plains Cree, he spoke several other languages and could read Latin and Greek. He was the official translator at the signing of Treaty Six, which led to many years of employment as a government translator and Indian agent.

Peter Erasmus was a tall, strong man. He was well educated and confident, shrewd and intelligent. Though he was not a chief or leader, he earned the trust of Native peoples, settlers and traders, missionaries and politicians. Through his honesty, hard work and resourcefulness, he was able to play more than one pivotal role in the turbulent times of the North-West Territories.

Adventure in the North-West

Peter Erasmus was born June 27, 1833 on his father’s farm near Fort Garry (Winnipeg). He was named Peter, after his Danish father. He was the fourth child born to Erasmus and his Métis wife, Catherine, also known as Kitty. When Peter was young, his mother told him many stories and legends from her Ojibwa family. Through her, he developed a lifelong respect for Native peoples and an understanding of their cultures.

Young Peter grew strong and lean and was accustomed to hard outdoor work. At the age of seven, he started school, a six-kilometre trek from home. He was an excellent pupil, but his formal education lasted only a few years. Peter’s father died unexpectedly when Peter was 13 or 14. He quit school to help on the farm, mostly looking after the livestock. But his life as a shepherd didn’t last long.

Peter’s uncle from Cumberland House came to Peter’s mother with a proposal. He was establishing a new Anglican mission and needed an assistant. He wanted to hire Peter, who would not only be paid to help at the mission’s school, but would also receive additional education. It was a great opportunity. In May 1851, Peter arrived at his uncle’s new mission. He worked as a teacher, instructing up to 30 Native children in the basics of reading, writing and Bible study. He quickly learned their language—Cree—developing a skill that would be the cornerstone of his life and later adventures.

Peter was a good teacher and continued to excel in his own studies. His uncle, along with several other church elders, right up to the bishop, wanted him to enter ministerial college, but the idea of a lifelong devotion to church work didn’t appeal to adventurous young Peter. His uncle, however, was so persuasive that Peter gave in and entered Anglican seminary school at Fort Garry in 1855. Peter tried hard to make the best of the situation, but by the end of his second term, he knew he was not destined to be a minister. Once again, fate stepped in to redirect Peter’s life.

He received an invitation from the Hudson’s Bay Company factor at Fort Garry (the head trader at each post was called the “factor” in HBC terminology). When he arrived, the factor greeted Peter warmly, saying he had known Peter’s father. Then he got down to business. Reverend Thomas Woolsey, the Methodist missionary at Fort Edmonton, needed a healthy, dependable young man to serve as a guide and interpreter. On the strength of his father’s good standing as a former HBC employee and Peter’s own attributes, the Fort Garry factor considered him a likely candidate for the job.

Stunned, Peter could only nod at this exciting prospect. Though he was trying hard to be a good student at the seminary college, he was unhappy. But this was a chance for adventure! He eagerly accepted the factor’s offer, almost ignoring the man’s warning that the bishop, who had sponsored Peter as a seminary student, would not be pleased with this turn of events. Despite the protests of the bishop and his uncle in Cumberland House, at the age of 22, Peter quit the college and set out for Fort Edmonton.

Woolsey’s Man

Peter took a boat up the North Saskatchewan River, bound for Edmonton. En route, he learned that Woolsey would actually meet him at Fort Pitt, some 130 kilometres east of Fort Edmonton. Peter stepped off the boat and into his new life in September 1856.

His adventures began right away. Woolsey had a number of horses with him, which he intended to use as pack and saddle animals. Although he was raised on a farm, Peter had little experience with horses, especially half-wild ones. Preparing to set out across the prairie the next morning, Woolsey saddled a horse for Peter, but when Peter approached, the horse pulled away, snorting and skittish. Peter was able to mount, but the stubborn horse refused to move forward with this inexperienced greenhorn on his back. At last, a young Cree man gave Peter a few quick tips on managing the horse, and off he went at a smart trot—much to the amusement of the gathered Cree audience.

On his second day, Peter got an education of a different kind. He and Woolsey came upon the scalped, mutilated bodies of several Cree who had been killed by Blackfoot warriors. For young Peter, it was a shocking introduction to the ongoing raids and warfare between the two nations.

Along with his new assistant, Woolsey spent the winter of 1856–57 at Fort Edmonton. He proved to be a kindly man and treated Peter more as a friend than as an employee. Peter’s duties left plenty of time for fishing and hunting expeditions with the other men living at the post. Peter’s experience with dog teams made him a valuable asset to the HBC factor. He was also an experienced fiddle player, another handy skill.

In the spring of 1857, Woolsey and Peter set out for Pigeon Lake, located southwest of Fort Edmonton—where Woolsey had a mission and a congregation of some 200 Cree. Here again, despite long hours spent labouring on the mission building and garden and translating Woolsey’s sermons, Peter had lots of time to hunt and hone his skills as a tracker and scout. With summer’s arrival, the Cree band broke up their winter camp and headed east to the prairie to hunt buffalo. Woolsey and Peter joined them. At every opportunity, Woolsey rode out to preach to other Cree bands camped on the plains. Peter was constantly at Woolsey’s side, translating back and forth between Cree and English.

By summer’s end, the Pigeon Lake Cree returned to their home camp at the lake and settled in for the winter. Peter passed much of his time joining the men on hunts, learning every detail he could absorb. But big game was scarce and the Cree were forced to venture onto the plains, once again in search of buffalo. Woolsey decided to accompany them, even though the cold took its toll on him. Woolsey was not a young man. He became very sick, possibly with pneumonia. Woolsey and Peter left their Cree friends and returned to Fort Edmonton, where they spent the remainder of the winter.

In January 1858, the factor at Fort Edmonton summoned Peter to his office. Once again, Peter’s skills had come to the attention of an important person. Once again, his life was about to take an unexpected turn.

The Palliser Expedition

In 1857, the British government sent an expedition of scientists and explorers to evaluate and report on the West’s resources and its suitability for settlement and agriculture. The man leading that fact-finding commission was Captain John Palliser. Working under him were Dr. James Hector, Thomas Blakiston, Eugene Borgeau and several others—each hand-picked for his particular background and skills.

Palliser requested the Fort Edmonton factor find a guide and interpreter. The factor offered the position to Peter. Coincidentally, Woolsey had just received a letter from his superiors telling him to cut costs. Though he hated to lose Peter’s services, it seemed the time was perfect for his assistant to take this new opportunity with Palliser.

Dr. James Hector arrived at Fort Edmonton in March 1858. Peter immediately liked this energetic, well-educated man. Hector was not only a medical doctor, but he had studied chemistry, botany, natural history, geology and paleontology. Hector gave Peter instructions and a long shopping list of supplies for the summer’s explorations, then departed for Fort Carlton. As soon as the river ice broke in the spring, Peter was to take provisions, horses and supplies to Fort Carlton.

By mid-April Peter was on his way. He set up a camp close to Fort Carlton and spent a few days hunting buffalo to furnish more meat for the expedition. When Palliser arrived, he assigned Peter a variety of general tasks, including care and feeding of the horses, setting up camp, hunting, guiding and interpreting as needed. Specifically, Palliser assigned Peter to accompany Hector in his numerous forays. Peter’s knowledge of the local landscape, birds, animals and Native peoples was invaluable to Hector, who in turn taught Peter to use surveying equipment.

At last, the party set out, bound southward over the open prairie, passing through herds of buffalo along the way. Their progress was slow because the expedition members were noting every detail about the land and mapping it as they went. After a long time, they reached Old Bow Fort, west of present-day Calgary, where they rested for a few days. Palliser then divided the group into several smaller parties, each of which took a different route into the mountains. The parties were to meet again at Fort Edmonton.

In mid-August, they began their trek. In the group with Hector were Peter Erasmus, Eugene Borgeau (a botanist), two other assistants named Brown and Sutherland and a Stoney man the group nicknamed Nimrod because of his hunting prowess. The group travelled light with only three pack horses. Nimrod assured Hector they would find plenty of game in the mountains for fresh meat.

Hector followed the Bow River westward, passing the locations of present-day Canmore and Banff. One day, near Castle Mountain (west of Banff), Peter tracked and shot a deer, but only wounded it. He continued to follow it through the forest. He was so focused on finding the deer that he lost track of time. Suddenly it was dark—and Peter had no idea where he was. Realizing it would be pointless to try finding his way back to camp, Peter built a fire and spent a long, uncomfortable night alone in the woods.

Well into the mountains now, the group left the Bow River, crossing the Continental Divide via Vermilion Pass. The terrain was rough and their progress was slow. Frequently, Peter and the other men were required to dismount and chop a trail through dense brush and deadfall. Hector often halted the group’s progress so he could take measurements, collect samples of rock, plants and fossils, or climb mountains. The men also hunted constantly. Contrary to Nimrod’s assurances, the group encountered very little game, and food supplies were critically low.

Late in August, the group reached a point near the present-day city of Golden, BC, and turned eastward. They found a turbulent, silt-laden river and followed it upstream toward the divide. The route proved to be very difficult—a narrow canyon with steep slopes leading down to the thundering river roaring below them. At one point, one of the pack horses slipped into the river, taking the group’s meagre food supplies with it into the frigid water. Hector, trying to rescue the animal, was kicked in the chest and fell to the ground. Alarmed, Peter and the other party members dashed over, but Hector did not respond to their calls.

There are a number of versions describing what happened next. According to one popular story, the group reluctantly concluded that Hector was dead. They dug a grave and were preparing to place Hector’s body into the hole when the “corpse” suddenly woke up. According to Peter’s own memoirs, the men carried Hector to a sheltered spot, where they made camp. Hector remained unconscious for most of the day. He eventually came around, and though his injury was extremely painful, his sense of humour was intact—he wryly named the stream Kicking Horse River.

The next morning, Hector was much better, but still in no shape to travel. Nimrod had gone out hunting. He limped back empty-handed, his ankle injured. With two members of the party unable to walk or ride, it was up to Peter to find food. He set off once again, this time looking for a herd of bighorn sheep that Nimrod had spotted. After some searching, Peter located the sheep and crept up on them. He was able to get a shot away and killed a big ram. He carried the meat back to the hungry camp. But due to the fall rutting season, the ram’s meat was rank with a musky odour and taste. It was inedible.

The party continued slowly up the river valley, climbing toward the divide. They found a patch of blueberries and feasted, though they still had no meat. The situation was desperate. Peter went out again the next day, but came back with only a partridge, from which Nimrod made soup using butt ends of candles for fat. At last, despite his swollen ankle, Nimrod hobbled into the woods to look for moose. Eventually the party heard a shot, and Peter scrambled off in the direction of the blast. The Stoney hunter had been lucky at last. Peter helped him carry the much-needed meat back to the camp.

The rest of the trip was difficult, though relatively uneventful. Satisfied with his accomplishments, Hector proceeded eastward out of the mountains, following the North Saskatchewan River. They reached Fort Edmonton on October 7, having covered some 900 kilometres in 57 days.

Peter passed another winter at Fort Edmonton. In the spring, Palliser was ready to set out again. He planned to explore the area that is now southern Saskatchewan and Alberta, after which he intended to split the group. Like the previous summer, each small party would explore a different route through the mountains. They were to rendezvous at Fort Colville, an HBC outpost in what is now Washington. Here the men would be paid and Palliser and his British companions would journey west to Victoria to catch a boat for England.

For the second time, the group journeyed south, well into Blackfoot territory. They set up a base camp near the Canada-US border. Peter and several others patrolled a large circle around the camp, scouting for evidence of Blackfoot. As they crested a hill, Peter spotted movement in the thick brush ahead. He told his companions to get their firearms ready, then they rode at a full gallop straight toward the spot, hoping to flush out the hidden warriors. The Blackfoot raiding party was taken completely by surprise. After a few minutes, when they were well away from the ambush, Peter noticed a pain in his leg. Looking down, he was astonished to see an arrow stuck in his calf. One of the other men cut off the long shaft, and Peter rode back to camp, where Hector patched him up.

The party had a number of other encounters with Blackfoot, Blood and Peigan bands. Though there were some testy moments, there was no further hostility. Palliser explored the terrain from the Rockies to Cypress Hills. The summer quickly waned, leaving little time for detailed mountain exploration. Though Hector asked Peter to accompany him into the Rockies, Peter declined, saying the food supply was too limited, the horses too tired and the season too late.

Hector was furious, but Palliser supported Peter’s decision, saying Peter had a perfect right to decline work he felt was too dangerous. Instead, Peter found his own way to Fort Colville to obtain his pay for two years’ service on the Palliser Expedition. Hector ventured into the Rockies once again. Despite his disappointment that Peter was not with him, Hector named a peak in Peter’s honour: 3,265-metre Mt. Erasmus, near the Howse River.

Searching for Gold

Officially released from his employment with Palliser, Peter was at loose ends when he was approached by two men needing assistance on a gold-prospecting venture. The men, Peter Whitford and Baptiste Anasse, offered Peter two-thirds of whatever gold they found. The catch: the prospectors had no money so Peter had to outfit the expedition out of his own pocket. He accepted their terms.

The trio set out for a spot where gold had been discovered. They were among the first to arrive at this remote location, somewhere north of Fort Colville (historians don’t know exactly where). Within two weeks, there was a makeshift town of tents and shanties. The three set up camp, built themselves a small cabin, and spent the balance of the fall working their claims. As winter approached, the horses were finding less grass for grazing. Finally, Anasse left to take the horses back to Fort Colville for the winter, while Whitford and Peter remained behind to guard the claim.

Anasse arrived back at camp in the spring, but almost immediately the two prospectors decided it was time to go back to Fort Colville and cash in their gold. Whitford found some eager miners to buy the claims, and the trio made ready to leave. In full view of the claims’ new owners, Whitford lifted a floorboard and withdrew two small pouches, presumably the gold that he and Anasse had amassed over the previous year’s work. The partners mounted up and departed. They rode hard and made a simple camp with no campfire. Anasse set up a decoy camp a few hundred metres up the trail, complete with log dummies under warm blankets and a campfire. Next, the three partners hid in the woods and kept watch through the long, cold night.

Peter detected movement in the dark. At least two men were creeping toward the false camp. One of them raised a knife over a dummy and brought the weapon down hard. Anasse and Whitford began firing. The would-be murderers instantly disappeared into the night, running down the trail to a barrage of bullets. Whitford strode into the false camp and pulled a long blade out of the blanket-covered log that was supposed to be a sleeping Peter Erasmus. He handed the weapon to Peter as a souvenir. But the night’s surprises weren’t over yet. Whitford made his way to a nearby pile of rocks, which he flung aside to reveal a duffle bag—the gold that Anasse had hidden the previous November when he took the horses to Fort Colville.

Treaty Six

Peter returned to Fort Edmonton and spent the next few years working for his old employer, Reverend Woolsey. The Methodist church had established several missions among the Cree in a large region northeast of Edmonton. At one of these missions, Peter met a young Cree woman, Charlotte, whom he married. Eventually Woolsey’s health failed. He was replaced by Reverend George McDougall—the man responsible for taking the sacred Iron Stone. But when George McDougall threatened to reduce Peter’s wages without taking a cut in pay himself, Peter quit.

Now married and without an income, Peter took to trapping and buffalo hunting to make money. The couple settled at Whitefish Lake, among a Cree band led by a chief named Pakan, also known as James Seenum. Peter ran a successful trapline and made several trips down the North Saskatchewan all the way to Fort Garry to see his family and trade his furs.

Then in 1876 two Cree chiefs, Big Child and Star Blanket, sent a message to Peter. The chiefs were to meet with representatives of the NWMP and the Canadian government to negotiate and sign a treaty. The Cree needed a trustworthy person to translate for them—to correctly interpret their wishes to the English-speaking government men. The chiefs asked Peter Erasmus to be their interpreter. Peter was honoured but reluctant to accept—Charlotte was about to have another child (their fifth), and Peter was uneasy about leaving her alone at such a time. But she insisted, telling him there were plenty of women in their Cree community who could look after her and the new baby.

Peter rode five long, hard days to reach Fort Carlton in time for the negotiations. As he was settling into his tipi, Big Child came to speak with him. The chief told Peter that the government had hired two other interpreters, but the Cree chiefs were determined to use Peter as their translator. The other two interpreters turned out to be Peter Ballenden and Reverend John McKay, both of whom had lived and worked among the Cree for many years. Peter knew both men, but he doubted the extent of their knowledge of the Plains Cree language. In particular, McKay spoke Woods Cree, distinctly different from the language of the plains peoples.

It was time for introductions and preliminaries to the treaty meeting. Along with the Cree chiefs and their councillors, Peter entered the tent where Lieutenant-Governor Alexander Morris and the other government men were seated. Big Child told Morris that the Cree had hired Peter as their interpreter, but Morris objected, saying that the government already had two competent translators on hand. Big Child replied, “You keep your two men, we will keep Peter to translate for us. We will pay him ourselves.” (Peter was quick to translate Big Child’s words into English for Morris.) Still Morris objected, until Big Child threatened to leave the negotiations. Again, Peter fluently translated the chief’s speech. Just as the entire event was on the brink of dissolving, Morris relented.

In the morning, the chiefs and councillors assembled in Morris’ large tent. Peter was summoned to the front table, where the government men were seated. He was bluntly told that he should translate Morris’ opening speech. This Peter refused to do, saying he was employed by the Cree, not the government. After speaking in English, Peter translated his own words into Cree for the benefit of the chiefs. Big Child asked Peter whether he was capable of translating the governor’s speech, to which Peter replied, “Certainly I can, or else I would not be here. Let their own men speak first, and you will understand why I refuse to do their bidding.”

Morris began his speech with McKay interpreting. McKay’s Woods Cree was peppered with words from other Native languages, especially Chippewa. Big Child was not impressed. Jumping to his feet, he shouted that the Plains Cree people wished to be addressed in their own language. McKay did his best to translate the chief’s angry words but became confused and stopped speaking. Peter Ballenden, the other government translator, then stood. As Morris continued his opening remarks, Ballenden translated into Plains Cree, but he mumbled and could not be heard in the large tent. Finally, the frustrated Morris personally called upon Peter to translate.

And so Peter Erasmus became the official translator for the Treaty Six negotiations. After Morris explained the treaty terms (and Peter effectively translated), the Cree chiefs spent the balance of that day and night talking among themselves and forming their response. The next day they assembled again, and Morris invited them to give him their concerns and opinions.

Poundmaker was the first man to speak. While many of the chiefs were inclined to accept the treaty, Poundmaker sought better terms. Morris gave a further explanation of the treaty terms, and the chiefs asked for another recess. The negotiations would resume in three days’ time. Meanwhile, Peter was called into the chiefs’ council meeting so that he would clearly understand the Cree’s concerns before they went back to Morris. The talks continued throughout the day with Poundmaker leading the objectors, but in the end, the chiefs decided to accept the treaty.

The chiefs came, once again, to speak with Morris. The treaty terms were read. There was more discussion and another recess. Poundmaker and his supporters tried once more to get better terms in the treaty, to no avail. Morris grudgingly agreed to some of these requests. At last, the discussion was complete. The Cree chiefs signed the treaty.

Morris called Peter into his tent and asked him to come to Fort Pitt for the second round of treaty discussions with the Cree of that area. Peter agreed. He arrived at Fort Pitt ahead of the government party and was quickly whisked into a council meeting of the chiefs to explain what had transpired at Fort Carlton. One of the chiefs, Sweet Grass, told the assembled leaders that he considered Big Child and Star Blanket to be wise. If the treaty was good enough for them, it would be good enough for him too. He announced his intention to sign. Pakan, leader of Peter’s own band from Whitefish Lake, also agreed. The next day, before Morris, all the chiefs in attendance repeated their support of the treaty, and the formalities were quickly completed. Peter was paid for his work. Still concerned about his wife, Peter soon left for home—a little too soon, as it turned out.

Big Bear, who had been hunting buffalo on the prairie, arrived after the treaty signing was complete and Peter Erasmus had departed. The man who translated Big Bear’s words did such a poor job that the resulting misunderstanding set in motion a chain of events that culminated in tragedy for Big Bear and his people. Had Peter been present when Big Bear arrived, the course of history may have turned out differently.

A Long, Long Life

The latter half of Peter’s life was more settled, though he had a mixed bag of jobs and employers. Morris hired Peter to perform translation and other duties. Peter was posted to the Cree reserve at Saddle Lake, some distance from his home on the Pakan reserve at Whitefish Lake. There was no place for Peter’s wife and family to live at Saddle Lake and he saw them infrequently. Tragically, one winter Peter received word that Charlotte was very ill. In his own memoirs, Peter says he arrived home just in time to say farewell to his dear wife, who died within a day of his return. In fact, records show that Charlotte passed away a week before Peter’s arrival. He remarried in 1882 and had three more children with his second wife, Mary, who also died young in 1891.

After the Riel Rebellion, Peter left Whitefish Lake, selling his cabin and ten acres of land to the federal government. He may have been forced into this action. All his savings had been deposited in a bank that failed, leaving him destitute. Luckily, he had a job and continued working for the federal Department of Indian Affairs. He moved east of Edmonton to the settlement of Victoria. His cabin has since been relocated to Fort Edmonton Park, a “living museum” and historical site in Edmonton.

Peter travelled back to Whitefish Lake to teach at the reserve’s school. He remained there until 1909, when he set out to Gleichen, east of Calgary. He stayed there for three years, then more or less retired at the age of 79. He lived with several of his children, moving from household to household, eventually finding his way back to Whitefish Lake. He died on May 28, 1931, at the age of 97.

Peter Erasmus

Glenbow Archives (NA-3148-1)