CHAPTER THREE

MONKEY SEE, HUMAN DO

I’ll say it again: imitating human beings was not something which pleased me. I imitated them because I was looking for a way out, for no other reason.

FRANZ KAFKA, “A Report to an Academy,” concerning the narrator’s previous life as an ape

SIGMUND HAD A MONKEY. THAT’S HOW MY MOTHER ALWAYS BEGINS the story. The Sigmund in question was my great-great-grandfather Sigmund Oppenheimer, and as a boy I tried to invoke this precedent to convince my mother to let me get a chimpanzee. Having a primate was a birthright.

Sadly, the denouement of the family monkey saga did not help my case. The creature (whose name has been lost in the family memory) would follow Sigmund around the house doing what monkeys do, aping his human. This included sitting on my great-great-grandfather’s shoulder as the old man shaved. My mother did not shield me from the tragic conclusion to this family tale. As you may have already guessed, one day when Sigmund was at work the monkey found the razor and, no doubt trying to emulate his human male, shaved for the first and last time.

It is not a mistake to think about men in relation to the males of other animal species. Such cross-species comparisons provide an especially accessible lens through which to understand what might be expected from males of all kinds. That we’re all animals and that we all come from common ancestors, way back when, is a bedrock understanding of life on earth. The raw intelligence of an elephant should awe us, but not surprise us, and when we underestimate the human-like qualities of other animals we do them a tremendous disservice. If the similarities were tested rigorously, we might find productive reference points to help in dissecting gendered issues among humans, including sex and violence. But caution is also warranted, because the significance of animals in our lives, and the ratification by science of what we believe is special about male animals, can lead us all too easily to exaggerate the extent to which men do things because they are male, almost as if they can’t help themselves.

We give human names to the nonhuman animals we keep closest, the ones who are practically part of the family. It is a way of marking the intimacy of our encounters. I wish I could give you the name of Sigmund’s monkey. We’ve put the family lineage maven on the case, but so far nothing has turned up from Ellis Island registries or Amazonian bills of lading.

Other than watching them at zoos, the closest I’ve come to communing with monkeys has been to live vicariously through primatologist colleagues, who study animals in forests, savannahs, and jungles, and are kind enough to return with their chronicles from the wild. When the primatologists recount their scientific parables, we learn of bizarro habits and routines along with the theories linking them to other species, best of all the human varieties. One hazard we need to avoid when it comes to comparisons with animals is cherry-picking from the animal smorgasbord when one or another similarity helps us make some broader point about human relationships. It is one thing to make animal comparisons to prove the validity of evolution. It is another to use them to shed light on human behavior today, as a mirror onto our own ways of mating, parenting, provisioning, fighting, and reconciling. Here we need special caution, because while there are abundant similarities, and greater knowledge of nonhuman animals does enhance our appreciation for their own complexities, we need to avoid falling into simplistic models for human behavior, including male sexuality and aggression.

The fact is that animal behavior is too multifaceted and varied to use as a trouble-free mirror on human activities. The greatest pitfall of overly inflating the coincidence of interests and activities of humans and other animals is that we can mistakenly ignore the context-specific environments in which all these pursuits take place. It is one thing to gain new awareness of the manifold splendors of nonhuman animals. It is another to reduce humans to one end of a one-dimensional animal continuum in the name of natural selection.

LEARNING FROM PETS AND THE DISCOVERY CHANNEL

A lot of what we learn as children about male behavior we learn through animals. Male dogs lift their legs to mark territory; tomcats can get aggressive when encountering one another. One of the results of urbanization throughout the world has been that people rarely have contact with nonhuman animals except as pets. Even if you didn’t grow up with pets—and chances are decent you did, because in 2018, Americans had 90 million dogs and 86 million cats—from childhood you read books featuring animals talking to each other and doing funny things, and watched television programs that featured animals, especially talking cartoons and nature programs that described the animals’ fears, hopes, and motivations. You had names and personalities for your stuffed animals. As an adult, you adopt a pet that feels like a family member, or marvel over the human-like antics of horses and goats.

Yet projection is a two-way street. Not only is our understanding of human male behavior filtered through our experience with nonhuman animals, but our study of nonhuman biology is deeply affected by our understanding of human males and females. And, not surprisingly, in virtually all serious accounts of male and female animal behavior, Charles Darwin is employed as a scientific talisman to wave over evolutionary tales, tall and other, about nature, nurture, and culture.

There are parallels with how we talk about people: sometimes we lump all humanity together, emphasizing commonalities despite superficial differences in appearance. In the same way, sometimes there is a point in lumping all animals together to trace their common evolutionary origins. The accent here is on shared phylogenetic origins, endocrinology, and ethology, our common humanity, animality, and shared life on earth.

But lumping has its problems. Sometimes generalizing about humans conceals meaningful differences, specifically inequalities. People can be different in virtue of the different ways they suffer, because of whom they love, or whether they pray five times a day or not at all. Erasing these complexities creates a false equivalence and can inadvertently reveal a lot about what different cultures do and do not value. So, too, with simplistic comparisons between humans and other animals.1

Our fascination with nonhuman animals, zoophilia, comes in boundless forms. Sometimes even a casual observation belies underlying cognitive schema about men’s animality. My friend Roberto in Mexico City gave me a tutorial on human-animal associations one day as he repaired radiators with his acetylene torch. With a fun-loving smirk, he tested my manly expertise when it came to wooing women.

“What does a woman need to feel complete, Mateo?” I responded by asking Roberto to educate me. “First, a cat in the kitchen,” Roberto said, adding, in case I couldn’t follow the allusion, “That’s someone who can help her with the cleaning and food.” He continued, “Second, a Jaguar at the door. That means a good car. Third, a tiger in bed. And fourth, an ox who supports her!” Only a true renaissance man, an all-around animal man, could satisfy a woman’s every need.2

But the zoophile’s poster boys are surely male primates, who are often presented to the public as displaying a range of unfortunate truths about mammalian maleness, siring, fathering, neediness, bossiness, and malevolence, along with a healthy dose of petulance. Bonus points when claims about silverbacks can be made apropos of their human male counterparts. Bruce Springsteen speaks for many of us when he sings, “Part man, part monkey, baby that’s me.”3

We have looked already at the science of maleness. Now we delve further into exaggerated claims of correspondence among males throughout the animal kingdom. The goal is not so much to avoid normative ways of thinking about male humans as to question what we take to be the norms for masculinity: men are far more flexible than an overdetermined biology of man allows. When we embellish the commonalities shared by males across species, we make ourselves more susceptible to a cross-eyed perception that the gender binary is as homogeneous for humans as it may be for other animals.

Children can learn about male and female from pets, television, and sometimes even stuffed animals. If they live in a city where most youths make it through high school, chances are they will pick up some basics of genetics and endocrinology along the way, including what their textbooks teach them about the importance of Y chromosomes, androgens, and estrogens. But for many, television nature programs are the most comprehensive source of information about animals and the science of maleness they will encounter. These shows are ubiquitous and available around the world. Television programs about nature are foundational for contemporary knowledge about boys and girls, birds and bees.

I know a retired factory worker in Shanghai whom everyone calls Teacher Li. When I asked him what he thought was different about men and women, he replied, nonchalantly, “hormones.” When I asked what he meant by this, Teacher Li replied, “Men’s hormones go up when they see pretty women.” When I asked Teacher Li where he came up with this idea, he told me, “Television, of course.” He was an avid fan of the nature shows that had become available in post-reform China.

As of 2017, the Discovery Channel claimed to reach over 400 million households in more than 170 countries, surpassing its media stepsister Animal Planet’s 90 million households. In recent decades, these shows have grown tremendously in popularity. As measured by reach, engagement, revenue, and the all-important “mind share,” Discovery Channel and Animal Planet by 2017 were winning among numerous demographic sectors and in various time slots for leisure viewing around the globe. Arguably the core lessons of these shows and the zany animal antics they present is, “Hey, they’re just like us!” Much of the world learns scientific and pseudoscientific information about animals and maleness from these channels.4

Nature programs tell us that piggish lotharios are common throughout the animal kingdom. Males of avian and mammalian species have some unvarying need to control their habitats, so maybe this is why societies look to men as the primary providers of hearth and home. It doesn’t take a genius to see something human in the way male goats, tigers, and sea lions fight for territory, and how females choose the winners of these contests as their sexual mates. These shows often find the same patterns of male behavior across the animal kingdom, and for many viewers there is some comfort to be found in that. Why are we so susceptible to suggestions that our own exploits, delusions, and desires are similar to what we’ve learned about mama bears and seahorses? Why does the notion of a sexually choosy male seem oxymoronic?

If people feel distress or confusion about gender relationships—for example, about men’s wolfish ways—this is real anxiety, and it makes sense that we might look for answers in television. If men are animals, and problems between men and women evolve from natural causes almost beyond our ability to restrain, then our confusion and stress about what it means to be male can be made more palatable.

ANIMALS ARE GOOD TO THINK WITH

Let’s readily acknowledge that animals are good to think about and with, and how often we do this as part of daily life. Animals are also good to swear with. Comparing someone to a nonhuman animal, as British scholar Edmund Leach remarked years ago, comes behind only sex, excretion, and blasphemy when you’re hurling invectives. Many of us sling around nasty animal analogies about males with great relish, often with a patina of naturalist rhetoric. In Spanish alone, men who are schmucks are called goats, lazy men are dogs, stupid men are donkeys, nasty men are pigs, and thieves are rats; a woman can be called a beast, a cow, and a foxy slut, and anti-revolution Cubans in Miami have been called worms. In China, you can call a male prostitute a duck and a female prostitute a chicken; ugly women are dinosaurs, ugly men are frogs; no one wants to be a turtle egg, and everyone expects children to be little monkeys. At the most extreme, biology and animality are held to practically dictate male behavior.5

Going back to Aristotle’s scala naturae, or “ladder of being,” defining the relationships between earth’s living creatures has challenged philosophers and recreational thinkers alike. René Descartes held that animals resemble nothing so much as ignorant machines. He never saw an android, but he did talk about the animal machine, calling animals natural automata. Two centuries later, Charles Darwin declared that all species share progenitors, and that we humans are unambiguously animals. The differences, he held, are matters of degree.6

To philosophers and poets animals often represent nature in its purest state. This tendency often serves to highlight our fear that humans are nature’s apotheosis, its biggest, cruelest failure. But the tenor of scientists is usually different. Animal studies and popular articles highlight apes that use sign language, dolphins that develop complex social strategies, and octopuses that manipulate tools to hide and defend themselves. They emphasize the animal in the human, and the humanity in the animal. For many researchers, a core issue has been whether “with rapid changes to human cultures in the last ten thousand years that far out-paced our ability to adapt physically… humans remained ‘suited biologically’ to the modern world.” For them the study of other animals makes it clear that our human cultures can never escape our common animal natures.7

Anthropomorphism—giving nonhuman animals, ghosts, or gods human characteristics—is central to our understanding of the history and unity of the animal kingdom, humans included. Only creationists seriously question the validity of cross-species commonalities. Problems with such juxtaposing, wisely employed, might appear at first blush to lead us into nothing more knotty than whimsical thinking. The appeal to hyperrealism, biologies, compulsions, and ever more ineluctable organic arguments about what constitutes bedrock maleness across the animal kingdom gives rise to a paradise of metaphoric possibilities, “Men are pigs!” being only too obvious.

As children quickly learn in comparing themselves to animals, we all eat, breathe, poop, make babies, sleep, and a whole lot more. Nonhuman animals are in some ways just like us humans. From aardvarks to zebus, from the most domesticated to the wildest animals, there are an awful lot of similarities in how we move about in the world. The issue is not so much how important these commonalities might be, but which ones are important, why we find them important, and how they can lead our understanding of maleness astray.

Many of us believe we have a good idea of what a pet thinks and feels, for example—we delight in our pets’ happiness and maybe feel a little guilty if they seem sad when we leave. We empathize with them, just as we’re sure they empathize with us when we’re sad. We can explain why we are fond of a particular species.

When Claude Lévi-Strauss said that “animals are good to think with,” he was examining “totemism,” an Ojibwa term signifying a kinship between particular groups of humans and special animals or plants that serve as their symbol, or totem. Central to the concept of totemism is an appreciation that nonhuman animals, too, have minds, and thus humans and totems can be linked through thought, although, as Emile Durkheim long ago wrote, totems really say more about human relations with each other. It was no small matter to associate the minds of human and nonhuman animals so directly, but Lévi-Strauss’s purpose was different. He was not so much crossing species boundaries as he was out to prove a point about the minds of humans: that they are all the same. Nonhuman animals were good to think with, in part because they could help us recognize this fact about humans.8

The philosopher Thomas Nagel famously asked, “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” The short answer was, who knows? Because humans surely cannot. Hang upside down in gravity boots like a bat, and you’re a human swinging upside down with clamps around your ankles. Tap into your undeveloped potential for echolocation, as some blind people report they are able to do in order to sidestep obstacles, and you’ve managed to avoid a tumble. We don’t pretend that because we humans and giraffes can walk that we know what it means to be a giraffe. Nagel’s point is not that bat-ness doesn’t exist, but that we cannot know what it is like to be a bat simply by looking at its behavior or studying its physiology.9

Imitation and imagination are central to the relationship between animals and humans, and not just for Disney. And what’s wrong with a little animal whimsy? Who gets to say if parallels are reasonable and appropriate? In the recent theater of animality, we see wrangling over animal boundaries with special poignancy, as other creatures are woven into performances to great effect for vicarious and subversive ends. All manner of bestiality is conjured up to shock us into thinking better about males, sexuality, and what comes spontaneously. When we take away the clothing, are males really so different?

Ordinarily we might think that evolutionary psychology and theater have little in common. But when it comes to animals, especially of the male variety, playwrights can exploit the same kind of common assumptions and prejudices about male animals—for example, that the males of all species will screw just about anything they can get their hands on, and do so full of self-righteous justifications for their actions.

Consider for a moment how Edward Albee’s The Goat, or Who is Silvia? projects human qualities onto an animal, the Silvia in question. Or does Albee have a human assume animal qualities? The plot rests on scandalizing social values guiding human-animal interactions, in what some call a theater of species, or a promotion of interspecies awareness. The Goat asks us to pity Martin and fear for him, a husband and father who with frenzied abandon is fornicating with Silvia, the ruminant in question. Martin insists he is helpless before the goat’s bestial charms, finding himself especially captivated after he gets a chance to stare into Silvia’s eyes: “She was looking at me with those eyes of hers and… I melted… I’d never seen such an expression. It was pure… and trusting and… and innocent; so… so guileless… an understanding so natural, so intense… an epiphany.”

Then again, Albee taunts us, maybe the logic here is that Sylvia is an animal who becomes humanized because she is the object of unbridled human male sexuality. Albee is not saying this is what all males are like; he is playing with the common belief in his audience that this is what all males are like. What is debated in the play is whether cross-species rape is, from Martin’s perspective, nonetheless a form of male sex. The play could not work were it not for that possibility: a man has sex with a farm animal. Far-fetched, but not entirely implausible. He is a man, after all.

Transgressive sex is not incidental or merely titillating in the play. The man-goat affair shocks because no words of affection or declarations of love can cover up the hideous vision of such an act of feral debauchery, just as images of Albee’s carnal being forever agitated his own family, who responded to their gay son with censorious cruelty. As Albee has Martin insist, “I thought I was; I thought we all were… animals.”

If men are just animals, it’s not clear what counts as unnatural.10

FRISKY BONOBO APPETITES

Among the most popular science writers today we find a remarkable number of primatologists, whose research and insights into ape behavior have become legendary. When Koko the gorilla, who learned at least the rudiments of sign language, died, there were major obituaries in newspapers across the United States. (The degree to which Koko could actually communicate this way was always debated.) Jane Goodall and her chimpanzee studies have made her easily among the most recognized scientists in the world. Tales of gorillas and chimpanzees have such currency today for many reasons, but surely one of the most obvious is what we believe we are learning about ourselves.

For many of us who read about science for pleasure, psychologist and primatologist Frans de Waal and anthropologist and primatologist Sarah Blaffer Hrdy are favorite authorities on all things animal. Their focus has always been on nonhuman primates, and their most important discoveries have been based on careful observation of other kinds of animals and not their own. But the analysis each provides holds implications for us humans, including with respect to masculinity and femininity, violence and peace, and sexuality. Nonetheless, as de Waal has cautioned, and no doubt Hrdy would agree, “we also abuse nature by projecting our views onto it, after which we extract them again, circularly proving whatever view we hold.”11

For centuries, we thought animals were entirely governed by unconscious instinct. But both de Waal and Hrdy have expanded our appreciation for animal choice and personality. In his many publications based on his work leading the Yerkes National Primate Research Center in Georgia, de Waal has repeatedly offered insights about where to draw the behavioral lines between animals, and how to develop our appreciation of how bendy those lines must be. Yerkes is one of seven national primate research centers funded by the US National Institutes of Health; it is located on 117 acres in Lawrenceville, Georgia, in rolling and wooded hills thirty miles northeast of Atlanta. When I visited in 2014, it housed over 2,000 nonhuman primates.

Arrival at the center feels like entering a military base, with all facilities fenced off, gates blocking entrances, signs warning not to take photos, and a security clearance checkpoint. Cameras and personnel monitor every movement on the grounds. De Waal meets visitors in an outbuilding with small offices and, alas, no distracting apes. Upon request, he sometimes allows them a quick observation from a position some distance from an internal fence separating off the chimpanzees.

De Waal has championed several enduring conceptual innovations based on his empirical work at Yerkes and elsewhere, among them his studies of bonobos, pygmy chimpanzees that share a common ancestor with the more common chimpanzees as well as humans. Merely 6 million years ago we were all one big happy species. Since then we have gone our largely separate ways, and one of the fascinating puzzles for primatologists is to figure out how these three species diverged. Often in his writings and interviews, de Waal chooses a particular trait he finds common to one or another ape and humans; through demonstrating similarities, he helps us to better appreciate the complex psychologies of apes.

With chimpanzees he has long railed against the mantra repeated in scientific and virtually every other quarter that chimpanzees are the closest evolutionary cousins to humans. De Waal believes that bonobos are just as close, but that we hear more about chimp cousinhood for reasons related to current beliefs about human males and females, sexuality, and violence rather than because of the actual evolutionary record. Chimpanzees spend more of their time than bonobos in aggressive activities (“Just like us!”); one common collective noun for a group of chimpanzees is “troop.” Furthermore, their troops are in nearly all cases dominated by males (“Just like us!”). De Waal grows weary of colleagues drawing overly simplistic comparisons between chimps and humans, showing that often the aim is to “explain” that human male licentious sexuality and eruptions of violence are in some fashion ingrained, because you can find what looks like similar behavior among chimpanzees. The simple fact that male gorillas and chimpanzees have less interest in sex unless a female is fertile, for instance, seems a rather basic difference that would remove these ape relatives from close comparisons with humans, at least with respect to sexuality, the kind of point de Waal never tires of making.

Because bonobos are just as close to humans as chimpanzees are, de Waal’s studies of them became especially important. Thanks to his research, we now know that bonobos have females in positions of high status, and that males and females spend a lot of their waking hours involved in sexual activities of wondrous kinds and combinations. This finding is directly relevant to humans because it shows a counterexample to chimpanzee male violence and alpha male social organization. The bonobos, in de Waal’s words, “show that our lineage is marked not just by male dominance and xenophobia but also by a love of harmony and sensitivity to others.”12

But here, too, we should be wary of looking too closely for human behavior. The fact that bonobos have sex with a range of individuals in their group, both same sex and opposite sex, whether or not the females are in estrus, distinguishes them not only from gorillas and chimpanzees but also from their human cousins. The fact is that humans, male as well as female, are far more picky about sexual partners than any of the other apes are.13

Throughout his many books and articles, de Waal seeks to make a middle run through the opposite poles of the same inanity: behavioralist scientists, for whom external stimuli (“conditioning”) is everything and biology means little, and those who see animals as automatons doing little more than responding to internal stimuli. De Waal makes clear that one reason this should matter, for those of us not employed to watch monkeys fight, hump, emote, or console, has to do with the Nazis: “After World War II, I think people were very obsessed with aggressive behavior and violence. And actually, if you read the old books on evolution of humans, it’s all about aggression. Everything was about violence and aggression, and all of the comparisons between humans and animals were on that front. There was a huge resistance to explaining human behavior biologically. It was equated with being a Nazi.”14

By the time sociobiology came along in the mid-1970s, and especially by the 1990s, however, de Waal saw a shift to the point where lectures on college campuses that explained sex differences in biological terms elicited yawns from students, who by then took all this for granted. Yet biology for de Waal, in particular, does not mean adhering to Victorian standards of gender and sexuality, or any other template in which males and females are by nature endowed with conspicuously distinct sexual appetites. And he is very much the historian of science when he notes that male anthropologists especially have had “a lot of trouble with the idea of female dominance much of the time among the bonobo. I never heard a female primatologist or female anthropologist tell me this is nonsense or this is not possible, or it’s trivial.”15

In addition to overturning gender refrains about what males and females do and don’t do across species, de Waal also doesn’t like to talk about innate biologies and instinct, because they cannot account for much of what he has observed, from “chimpanzee politics” to primate reconciliation, empathy, and emotions in general. Beyond tool use, de Waal has written effectively about altruism, sexual orgasm, humor, cooperation, theory of mind, self-awareness, social reciprocity, and more among our ape cousins.

He never shies away from delineating boundaries, such as communication (“I don’t think apes have language”) and fathering (“We are the only animals… with the concept of paternity as a basis for fatherhood”). These are not trivial differences for him. But he doesn’t particularly endorse the term “nonhuman animals,” insisting that, as with Darwin, it’s all a matter of relatedness of animals of various kinds. De Waal’s central mission seems aimed at raising our human awareness and regard for the fundamental capacities of other animals, especially those closest to us.16

“In relation to our close relatives,” he told me, “I think there’s nothing wrong with anthropomorphism, even though I would always add that you still need to check if it is the same thing that you are seeing. But if you get to very different species, let’s say two octopi embrace each other, that may not be the same sort of embrace as you will have as a human being.” Anthropomorphism works for de Waal, and he thinks it should be more widely adopted by the rest of us.17

BANISHING COY FEMALES

Male apes are often seen as proxies for human males when they are believed to exhibit a pan-creature male attribute. But as with humans, you can learn a lot about male ape behavior by looking at female apes instead.

It is no accident that Sarah Blaffer Hrdy came along when she did in the 1970s, a time of heightened turmoil about gender and sexuality among humans, and revolutionized our understanding of female ape sexuality. She delivered a conceptual body-blow to long-held notions of sexual docility among female primates, and in so doing, in effect overturned long-established preconceptions about what distinguishes mammalian male and female sexual activity. The main purpose of her first pioneering work on langurs was not to gain insights into human females and males, but there can be no doubt that the feminist movement at the time was a background for her interests and findings. In addition, through Hrdy’s primate studies we have been better able to recalibrate our underlying assumptions about male and female more broadly, leading to further clarity about mistaken assumptions, and perhaps not a little gender disorientation, too.

Squeezing facts to wedge them into preexisting theory can be a problem in any scientific field. Evolutionary psychologists are widely accused of selectively mining animal behavior for their models with the endgame purpose of showing some human activity as stamped with a Darwinian Seal of Evolutionary Approval. Sarah Hrdy is the exceptional sociobiologist who has been willing to rethink hallowed truths based on new evidence. And as she would be the first to note, the fact that she is a woman and that most of her major discoveries have to do with female primates is entirely to the point. Before Hrdy, few if any scientists studied female primates with as much care and open-mindedness.

In reconceiving several basic beliefs about female primate behavior, Hrdy has rewritten the book on mothering, allomothering (when other females help in parenting), infanticide, primate sexuality (including with respect to female coyness, sexual assertiveness, polyandry, and promiscuity), and sexism in the sciences.

Consider the following numbers that come from observations of others but in Hrdy’s hands take on new meanings: a female chimpanzee may well have 6,000 copulations with dozens of males in the course of her life and give birth to five offspring. Standard-issue biology courses teach that males are profligate and females modest and choosy. Hrdy demolished the notion of the textbook coy female, showing that, in case after case, when anyone (i.e., female primatologists) bothered to look, lo and behold, plenty of female primates were scampering around and copulating even when, god forbid, they were not in estrus. Maybe they liked sex?18

In studying langurs and libido, Hrdy admits that it has been hard to restrain the urge to extrapolate to our species: “Once acquired, the habit of comparing humans with other primates is hard to shake.” When I mentioned to her that Frans de Waal had said something similar to me, she chuckled and replied, “I refer to him as my only adult colleague.”19

Yet she is comfortable delineating between humans and animals. “Across cultures and between individuals, more variation exists [among humans] in the form and extent of paternal investment than in all other primates combined.” As for paternity, and whether human males ever know for sure who their offspring are—long “an obsessive focus for evolutionary interpretations of male behavior”—for Hrdy, paternity uncertainty “is only one factor influencing men’s nurturing responses to babies.”20

The key is to test, and when necessary to disprove, existing presumptions about primates. Many of the beliefs she ended up dislodging had to do with an overly dichotomous model in which female primates (including female humans) were sexually demure, and male primates had an insatiable craving to mate with as many females as they possibly could. According to Rebecca Jordan-Young, a multidisciplinary researcher who studies the science of sex differences, the male-as-predator, female-as-passive-receptacle template prevailed in studies of sexuality until the 1980s: it was not simply that male and female were distinct, but that they were seen as polar opposites, a model in which female sexuality “followed a sort of romantic, sleeping-beauty model.”21

Sarah Hrdy overturned implicit assumptions that female behavior boiled down to maternal behavior, and therefore, among other things, that sex could not be an end in itself for female primates. Her peers had long intoned “only hundreds of eggs, but billions of sperm… hundreds of eggs, but billions of sperm,” as if these numbers in themselves proved that males as a group are sexually voracious—that they could afford to “waste” sperm, whereas females had to be sexually judicious to make every one of their precious ova count.22

One of Hrdy’s early studies was especially poorly received by both certain feminists and sociobiologists. Based on her own work in the 1970s with langurs in southern India, she came to the then-astonishing conclusion that polyandrous mating by females was more widespread than had been understood, and for some primates it was downright normal. The feminist concern was that Hrdy linked biology too closely with sexuality. The sociobiologists expressed alarm because this notion challenged some basic premises of their evolutionary theory: polyandrous females simply did not fit with the dominant existing theory that (1) females need male provisioning, (2) if females were to engage in multiple couplings with many males they would risk forfeiting this male commitment, so that (3) males may couple widely but females have an inbuilt incentive to be more selective. The implications for female and male primate sexuality were shocking.23

The cherry on the top of this revisionist sundae was the extension of Hrdy’s analysis from the apes to humans, and speculation about the origins of “patrilineal interests” among humans. Prior to the Neolithic (roughly 10,000 BC), Hrdy believes, “women would be most likely to mate polyandrously with several men where support from matrilineal kin (including help provisioning young) provided them the social leverage to do so.”24

Combine that with the tantalizing theories about female sexuality recently advanced by ornithologist Richard Prum on the evolution of beauty—“Because the female orgasm has evolved through a purely aesthetic evolutionary process of mate choice, women actually do have the capacity for greater sexual pleasure than men, and women’s sexual pleasure is more expansive in quality as well as extent”—and you have all the fixings for a radical new appreciation for the capacity of not just our bonobo cousins, and not just our males, for lifelong, lively sexual encounters.25

ANTHROPOMORPHISTS GONE WILD

How do we know when we’re pushing animal comparisons too far?

For most of us, everyday anthropomorphism centers on the attention we lavish worldwide on our 600 million cats and 500 million dogs, under observation and interacting with us round the clock, those pets with human names and personalities. Nonhuman animals may be humanized: treated as sharing basic qualities like sentience and volition, as having more of an individual mind than a pack mentality, and sometimes even as possessing consciousness, in the sense of having memory of the past and expectations for the future. Nonhuman animals are anthropomorphized so that they can be elevated. When humans become animalized, however, they are in effect dehumanized and degraded. They lose their singular qualities. They are thought to surrender to herd impulse. They lose much of their self-control and ability to choose.

It is not easy to find the borders between acceptable and insupportable anthropomorphism. Where do we draw the lines, especially when thinking about men as animals? Notre Dame primatologist Agustín Fuentes offers a clue: “It’s a commonly held belief that if you strip away culture, that which keeps us well behaved, then a beastly savage will emerge (especially in men).” The closer we get to the idea of men as animals who cannot control themselves but need to be kept in line, the more we should exercise care in our language and presumptions.26

Anthropomorphism among paleoanthropologists—whose attention is keyed to ancestors who knuckle-scraped the earth millions of years ago—logically enough often focuses on how close in time we are to a shared ancestor. We parted ways with the ancestors of orangutans 14 million years ago. With gorilla-human progenitors, it was 8 million years ago. And as we know, as to the foreparents we share with chimpanzees and bonobos, the fork in the evolutionary road was as recent as 6 million years ago. Almost by definition, we must therefore share more habits of heart, mind, and genitalia with chimps than gorillas, more with gorillas than orangs. The closer in this scale of time, the more the same nouns and verbs are used to describe our respective behaviors.

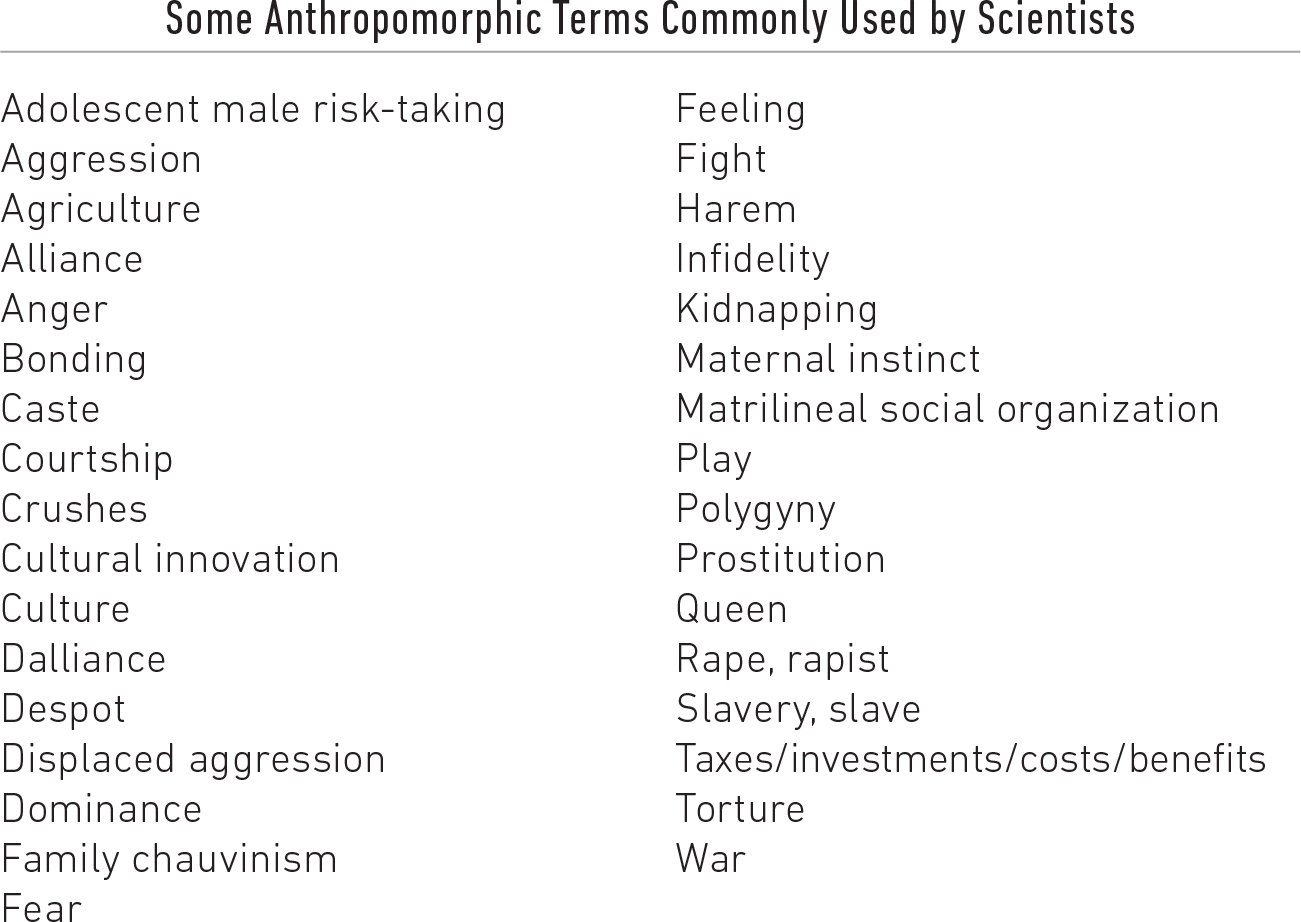

Look at the many terms listed in Table 2 that are employed widely by zoologists and primatologists to describe nonhuman animals. Take your time decoding and considering which ones seem most reasonable and which are too laden with uniquely human stamps to be usefully applied to other animals. (Hint: specialists debate the utility of employing these terms all the time.) Put an “A” (for appropriate) or an “I” (for inappropriate) next to each one.

Why you put an “A” or an “I” is the question. If “anger” seemed to you to work across the species board, why not “slavery”? If “alliance” seemed like an appropriate way to characterize marauding hordes of monkeys, then why not call the ensuing conflict an example of monkey “war”? We hear these terms used, and we use them ourselves, and rarely think twice about the implications of drawing such tight parallels between the actions and feelings of nonhuman animals and our own behavior and emotions.

No one really expects that nonhuman animals use speech to converse, but anthropomorphic talking animals are always popular—and at least for the genus of Equus they can trace their ancestry back to biblical times. In Numbers 22:28–30, we read, “And the LORD opened the mouth of the ass, and she said unto Balaam, What have I done unto thee, that thou hast smitten me these three times? And Balaam said unto the ass, Because thou hast mocked me: I would there were a sword in mine hand, for now would I kill thee. And the ass said unto Balaam, Am not I thine ass, upon which thou hast ridden ever since I was thine unto this day? was I ever wont to do so unto thee? and he said, Nay.” It took the miracle of a talking donkey to get through Balaam’s thick skull that the Lord wanted him to wake up and find the righteous path.27

Every primatologist uses certain of these human categories to describe the behavior of nonhuman species. The vocabulary most readily at hand is what is used to describe human relationships and acts, and many try hard to find apt replacements for words that crudely anthropomorphize animal behavior. Anthropomorphic terms can seem applicable—“Those male monkeys are fighting.” They can be a playful way to compare nonhuman animals to humans—“That female monkey is presenting to that male.” And they can be a fabulous way to gain insight and sympathy for animals—“That female monkey is a good mother.” Perhaps we should leave it there. If we’ve learned anything in the past few decades it is that nonhuman animals have far more varied and rich lives emotionally, organizationally, and sexually than we ever realized.

In order to think more critically about anthropomorphism we need to allow for the foundational reality of evolution and our common origins as well as for the (just as real) abuse of human-animal comparisons. These comparisons often reveal more about social and cultural bias than they do about similar cross-species’ motives or meanings. This will become clearer if we take a closer look at three recurrent, contemporary examples of what can happen when anthropomorphism is given free rein. These examples demonstrate how three terms in particular, first built on flawed notions of male and female sexuality as polar opposites, serve to reinforce these mistaken preconceptions. They are hummingbird prostitutes, baboon harems, and mallard duck gang rape.28

Prostitution in this case is a way to talk about female hummingbirds “offering” the male hummingbirds sexual congress in exchange for something else—twigs for a nest, for example. Offering what certain ornithologists regard as the female hummingbird point of view, hummingbird sex appears transactional, and that seems (to certain birdbrained scientists) the essence of human prostitution. The unstated premise is that males and females (hummingbird and human alike) have sex for dissimilar reasons, which for the females is to get something besides sex. The parallel between hummingbird and human affects how we understand hummingbird behavior, and more importantly, for our purposes, also reinforces the idea that there is something natural (and maybe, therefore, necessary) about human prostitution, and that females of both species have sex for reasons other than sexual pleasure.

The term “harem” is used even more widely among scientists, to describe a scene in which single males—for example, baboons—have sex with many different females, which is, at best, an American teenage boy’s interpretation of a harem. I have yet to see one primatologist use the term “harem” with so much as a sentence defining what he means by harem, much less an inkling of an informed description or a semblance of an analysis of the shape, texture, rationale, history, and lived experience of any human harems.

In one account after another of mallard duck behavior, the term “rape” is applied with relative shamelessness. Sometimes we read about “forced copulation,” which is a step in the right direction. But even there, given that human rape could also be called forced copulation, we remain in semantic quicksand. Groups of male mallard ducks do coordinate what we can call attacks on single females, with the end event of a male copulating with the female duck. Male mallards engage in such attacks as part of routine behavior that impregnates the female. Of significance, however, ornithologist Richard Prum reports, “In several duck species, including Mallards, in which the forced copulations are a stunning 40 percent of the total copulations, only 2–5 percent of the young in the nest are sired by a male who is not the chosen partner of the female. Thus, the overwhelming number of forced copulations are unsuccessful.”29

Male mallards do not attack female ducklings in this way. They do not attack other males in this way. And crucially, if you follow a male mallard duck, you will be witness to this kind of behavior nearly half the time. In what world could you say the same about any human male you know? There may be some male mallards who are more successful than others with these attacks, but there are none for whom this is abhorrent behavior. Thus, to equate the actions of mallard ducks with human gang rape requires us to see rape as fundamentally instinctual for males across species, and to understand a human woman’s consent (or lack thereof) as fundamentally equivalent to a duck’s.

If challenged, those who use these terms often admit they are meant to be memorable more than precise. It’s true that exaggeration, surprise, and analogies are all useful instructional tools. But relying on them to this extent has taught us to overidentify with particular animal behaviors and then implicate instinct or nature as the source of individual and culture-specific human activities. When psychologist Steven Pinker writes that “infidelity is common even in so-called pair-bonded species,” we just have to ask: If infidelity is premised on marriage vows, then when did the invitations go out for those weddings? The fact is that Pinker or I can be party to infidelity, but the swans on the Charles River cannot, any more than can prairie voles or shingleback skinks in their habitats. Infidelity is a uniquely human experience. To call swan sex with more than one mate infidelity obscures what and why swans do this, and more importantly, it naturalizes human adultery beyond reach.30

Among the many omissions in each of these cases of anthropomorphism is that with virtually every behavior, human males and females show more variation than has been observed among males and females in any other species. So while it is entirely predictable that a male mallard duck, for involuntary reasons of reproduction, will engage in what some call gang rape, this is absolutely not the case for human males, where rape is a matter of social power and prerogative. Even when gang rape occurs during wartime, it is not the biological maleness of the rapists that causes it. To call what mallard ducks do gang rape has real consequences undoubtedly beyond those intended, because this language can inadvertently lend seeming biological support for gang rape among humans.

Rarely does a researcher compare humans and animals in an all-inclusive manner. No one says that human males are entirely like chimpanzee males. Rather, particular traits are selectively employed to bolster a larger contention. To be sure, we share a common ancestry, and our DNA is remarkably similar to that of chimpanzees. But if that’s all it takes to make meaningful comparisons, we might also note that human DNA is 35 percent similar to that of daffodils, which really gets us nowhere.31

ANTHROPODENIAL

The flip side of extreme anthropomorphism is what Frans de Waal calls anthropodenial, a term he defines as “the a priori rejection of shared characteristics between humans and animals when in fact they may exist.” If your main concern is an underappreciation of animals and their emotional complexity, you may bend the stick more in the direction of warning against rejecting common patterns. If your main concern is human gender relations, however, it is not hard to see that overdone comparisons can lead to a different set of problems clustered around the notion that human males behave more in sync with one another than is the case, and are compelled by their bodies, not decision making, to do things like committing rape. Human rape is a choice, not an accident or a hardwired compulsion.32

It has not been just humans that continued to evolve over the past several million years. De Waal writes, “People often think that the apes must have stood still while we evolved, but genetic data in fact suggests that chimpanzees changed more than we did.” So looking at chimps and bonobos as somehow illustrative of what “we” all were millions of years ago is deeply flawed. For de Waal, “the key point is that anthropomorphism is not always as problematic as people think. To rail against it for the sake of scientific objectivity often hides a pre-Darwinian mindset, one uncomfortable with the notion of humans as animals.” He is talking about creationists, and his point is watertight.33

The rub is that even for people who have no problem acknowledging that humans are animals, anthropomorphism can have negative effects, and it’s good to be wary of some of them. If I mention to a queen ant that I admire her majestic ways, she will not know the difference. I can call her anything I like and it will not affect her in any way. But if I talk to my barber about slavery among ants, tell him that slavery is something that is found cross-species, that it’s actually not uncommon, that human slavery is not the exception but almost the rule in the animal kingdom, it could sound like I am saying something fundamental about human beings, too. I could leave my barber with the impression that slavery is natural, and therefore, as awful as it is, pretty much impossible to ever eradicate from human societies, just as it is impossible to eradicate it from ant societies. The words we use and the meanings behind them influence how we understand human relationships and events. They can cause trauma—to people, not ants—for generations after slavery.34

Humans have their uniqueness, and they have their Umwelt, their animal point of view and particularity, and we need to appreciate that. Talking about slavery among other species can do more than trivialize human oppression; it can spread ideas that support it. If people learn about a coming hurricane, this does not change their beliefs about the weather patterns that caused the storm. But if they hear about “slavery” among ants, could this not change their beliefs about what has given rise to slavery among humans?

It is one thing to insist that we extend to other animals features that previously were held to be uniquely human—in a sense, to humanize the animals. Anthropomorphism can be lighthearted and a mnemonic device to make sense of the world. But we need to be precise. As one who studies the human species, I feel it is particularly salient to humans (and their core cognitive abilities) how we characterize them and their affinities to other species. It doesn’t mean that we can’t or shouldn’t find continuities and parallels. It does mean that psychological and sociological profiling can have a lasting impact on humans. De Waal quotes Mark Twain: “Man is the only animal that blushes—or needs to.”35

And, speaking of blushing, that is a quintessential experience that is highly gendered (and racialized) among humans. In the English-speaking world, white women blush. White men turn red. And that, too, speaks volumes about anthropomorphism, because nowhere does it have more impact than in making analogies about male and female among different species. When metaphor and analogy make human activities like harems and infidelity look “natural” because they are said to appear throughout the animal kingdom, we fall into the trap primatologist Stephen Jay Gould warned against:

Metaphor is a dangerous, if ineluctable, device. We use images and analogies to foster understanding of complex and unfamiliar subjects, but we run the risk of falsely infusing nature with the baggage of our parochial prejudices or idiosyncratic social arrangements. The situation can become truly insidious, even perversely so (in the literal rather than pejorative sense), when we impose a human institution upon nature by false metaphor—and then try to justify the social phenomenon as an inevitable reflection of nature’s dictates!36

I teach a course on gender and science and use the examples of hummingbirds, baboons, and mallard ducks to discuss their relevance for human gender relations. I ask the students if evolutionary overrides could apply to humans as well. Discussion is always lively, and there is rarely uniform agreement. One year, a week after this lecture about applying the labels for complicated, historically grounded human relationships to nonhuman animal behaviors, a young woman came to class and shocked us. She had in the interim attended a biology class in which her professor had instructed the students on the workings of “gangbanging bacteria.” You decide: witty or warped?37

Anthropomorphism might make the study of nonhuman animals, or bacteria, more user-friendly and easier to understand. Except if you happen to be a person who has been the target of a very human gang rape—or any other assault, for that matter. Why take these clever and transparently over-the-top comparisons so seriously? For so many reasons, not the least of which is the normalization of rape as a part of nature. You can joke this way to a bacterium all you want, calling it a gangbanger or anything else, and I would wager my tenure that the bacterium will not be offended. Talk of rape and its ubiquity among human organisms in this way, however, and listeners can draw lessons that are nothing short of felonious.

When scientists uncritically anthropomorphize not just about other animal species but even single-celled organisms, it is hard to know whether to be outraged, or just relieved that the comparison is so outlandish that no one could take it seriously. We can find plenty of evidence that discussion about what is naturally male across animal species has always been prominent in otherwise very different societies. Aristotle memorably wrote on zoology; before Aristotle, Confucius contemplated the relationship between humans and other animals. But an emphasis on men’s animality has particular consequences and potency today. We are at a crucial moment in gender history, one in which we need to get better at broadening our definitions about what it means to be a man.

Too often, anthropomorphism has served other animals better than it has served humans. If our aim is to appreciate the range of qualities our primate cousins embody and express, and that there are indeed profound and abundant similarities between chimps, bonobos, and humans, point well taken. But if the aim is to use human relationships to characterize nonhuman ones, and then turn this back to imply that because these are shared traits they will always be with us (or with us until evolved out), that’s not just careless anthropomorphism, it’s ape abuse.

Here’s the crux of the matter: we should never lose sight of the critical fact that all animals vary in their behaviors, and that human males are exquisitely malleable, having a range of behavior markedly greater than those of the males of any other species. Humans don’t have to act like other animals. Believing that we do is reckless. To lose sight of human mutability and the range of behavior among humans is to give men a morphological free pass to tyrannize others under the guise of “acting like a guy,” and to offer men the impunity of evolutionary inheritance for a defense.