CHAPTER EIGHT

REVERTING TO NATURAL GENDERS IN CHINA

The Utopia of this century—that which has been desired above all else, and desired most deeply—has been the modernization of body and soul.

CARLOS MONSIVÁIS

PERHAPS NOWHERE IN THE WORLD HAVE CULTURE AND NATURE been put to the test in recent decades more than in China. Say what you will about Maoism, if you come from a country that has never managed to pass a piece of legislation called the Equal Rights Amendment, the idea of at least lip service from the government for full gender equality might seem refreshing. In the most horrific days of Maoist upheaval, women and men in China were declared equal juridically and socially, and generations of women saw notable improvements in their educational, social, and economic expectations.

THE REASSERTION OF MALE PREROGATIVE (AND FEMALE ACQUIESCENCE)

Achieving gender equality in education levels and job assignments was official policy in China from 1949 until roughly 1979. During the Maoist period, the slogan “Women Hold Up Half the Sky” implored a generation of radical youths around the world, both women and men, to work toward societies in which gender equality was a reality. It was among the most important mantras of China’s Cultural Revolution. In post-Mao Reform China—from the late 1970s on—women have been encouraged to raise and limit their sights simultaneously, whereas men have been encouraged, in official and unofficial ways, to reassume their mantle as patresfamilias. Few look back on the drab unisex clothing of the Maoist era with nostalgia—just the opposite, as ornate white wedding gowns were nowhere more popular than in China in the 2010s. But many acknowledge that at least there was the pretense of sartorial equality.1

Sociologists Jun Zhang and Peidong Sun write, “During the Maoist period, status and income differentials between different jobs and between men and women were relatively small.” And the expectations parents had for daughters and sons were similar. After the reforms of the 1980s, anthropologist Mayfair Yang, looking back, said, “What is astonishing is the rapidity of the return of gender differentiation, the ascendancy of the male gaze, and masculine sexuality’s domination of a public sphere partially vacated by the state.” Gender differentiation takes different forms in contemporary China, but it always entails men realizing a greater share of prestige, power, and control at home, at work, and throughout the country.2

No one would claim that today’s sharp distinctions between men and women, their natures and their activities, are new in China. But scholars argue persuasively that even in historical periods long ago, in which discrimination against women was widespread, the distinctions were looser than they are in contemporary China today. They did not have “the same totalizing, universalistic, and rigid essentialism that modern biology introduced into the Western [gender] binary,” according to Yang.3

Under a 1950 Marriage Law, Chinese women won new rights, formally and often in practice, to own property, to divorce, and to exercise freedom of choice in marriage instead of abiding by arranged marriages, child marriages, and the buying and selling of women for marriage. Regardless of what women achieved after the 1949 socialist revolution, many young women in China in the 2010s were expected to reverse course. Although it is the women who have experienced these transformations most directly, men have been witnesses to them over the past seventy years. Often the targets of criticism, ridicule, and opposition during the Maoist years, more recently they have become the full beneficiaries of practices that again openly favor men and patriarchal forms of masculinity.

Between 1982 and 1998, most of the housing in China was converted from collectives to private home ownership. By the 2010s, China had one of the highest home ownership rates in the world, around 85 percent. This astonishing transformation had an immediate and momentous impact on young men and women and on courtship, marriage, and relationships with in-laws. Housing was where most of the private wealth in China could be accumulated and maintained, and it suddenly became a key symbol of emerging gender differences. In 2010, when the All-China Women’s Federation and the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics surveyed over 100,000 people, they found that only one in every fifteen single women owned her own home, about 7 percent. But they found that one in five single men owned his own home, or 20 percent.4

For young couples who lived together but were not married, it was far more likely that the young man owned the home than the young woman. Furthermore, as private ownership of housing swept through urban areas, often only one name was required on the property deed, and that one name was usually the husband’s. In case of divorce, it is not hard to see where this left ex-wives. As housing became privatized in cities, tensions intensified and became focused around a young married couple’s first home.

In 2009, Gu Yunchang, vice president of the Association of Chinese Real Estate Studies, was quoted in the newspapers pronouncing, “The rise of housing prices is due to demands from [grooms’] mothers-in-law.” When pushy brides and mothers-in-law on either side were castigated for demanding apartments from young grooms, more than objectionable ideas were in play. The widening disparity between men and women when it came to property ownership—and the implicit assertion of a male birthright to own and control housing, and all new family wealth, under the post-Reform regime—was also evident.5

Marrying off one’s child in China is related to grandchildren and is related to housing. And it’s related to who will take care of the grandparents as they age. The exigencies of growing old, of eldercare, and of the new conditions in post-Reform China are connected to spreading gender chasms and “leftover” unmarried women. The phenomenon of the leftover woman has occurred despite selective abortions of female fetuses during the era of the one-child policy, as described later in the chapter, and is closely linked to the fact that these abortions historically took place overwhelmingly in the countryside, while the contemporary issue of leftover women is tied to the demographics of young women in cities and the social disruptions caused by migration and urbanization. A growing crisis in eldercare is apparent in China: old social structures and relationships that drew on collective and kinship networks are less and less tenable, or they no longer exist at all. Not surprisingly, if women decide to remain single, the care of elderly parents becomes even more problematic.6

In 2011, sixty years after the Marriage Law of 1950, underlying legal support for gender equality in home ownership came under direct challenge when China’s Supreme People’s Court took major steps to dismantle key provisions. In particular, women’s property rights were severely reduced. After this point, women had far more difficulty keeping their homes after divorce, because the ruling gave explicit preference to leaving marital property in the hands of the person whose name was listed as the owner of the home. That person was almost always the husband. The 2011 decision was an important step in purging the goal of gender equality from the legal statutes governing marriage and property rights.

Women have lost ground in recent decades in China in other quantifiable ways as well. In urban areas throughout the 1970s, women’s income was estimated to be 85 percent of men’s, a figure that compares quite favorably to those in the United States at the same time. Following the reforms, things went in the other direction, with women’s income sliding down to 70 percent of men’s. Women were forced to lower their sights, and men increasingly were expected to provide the primary salary and other financial support for families. These were no longer considered joint obligations and rights in families, either juridically or in everyday practice.

China is one of the only countries in the world with a higher suicide rate for women than men. This statistic may be an indication that, despite headlines about tens of millions of bachelors in China, men have it better there. When we look more closely, however, the patterns that seem most relevant to understanding contemporary beliefs about men and their bodily components in China often adhere to urban and rural differences, and within those divisions, matters of class. In China perhaps more than in any other country in recent years, conservative, backward-looking ideas about men and their ways have been reinforced from on high and from below. Over the nearly thirty years since the state-sponsored objective of gender equality was put to rest with the reforms of the late 1970s, the gender binary has roared back with a vengeance.

But although the gender binary seems stronger than ever in China—with booming sales of white wedding gowns providing Exhibit A—that doesn’t tell us why. Although some of the reasons are likely similar to those we find in other countries, what we might call the gender binary with special Chinese characteristics is remarkable for its unique qualities. Recent scholarship has pointed to several modern historical factors in its comeback.

In a country where the historical record is summoned with casual frequency in everyday conversations, at the core of understanding masculinity and femininity in China today is the need to bury the shame of the past—in particular, avoiding a return to the days of the anemic literati who proved themselves ineffectual against the disgrace of foreign subjugation during the final decades of the Qing dynasty in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Consensus on the gendered aspects of that humiliation is unanimous in China, and preventing a repeat is a commonly declared goal. That doesn’t mean that everything foreign is shunned today. The backlash in the post-Reform period against the prior Maoist “cult of chastity” is intimately connected to the appeal of global cultures of gender for the middle classes. When the Chinese in the 1980s and 1990s were looking around at what the rest of the world considered modern versions of men and women, they drew special inspiration from markedly dichotomous relationships between the sexes in Japan and Taiwan.7

We can add to these explanations two others that have fueled and channeled the renewed attraction to the gender binary in contemporary China: one concerns the one-child policy beginning in the late 1970s; the second has to do with the failure to integrate women into the top leadership positions, despite the aim of achieving gender equality. During the era of the one-child policy, the role of the woman in the family as the (primary) caregiving parent and of the father as the (primary) breadwinner became more pronounced as a social model. As for the second factor, both historically in general and during the age of Maoism, men ran the institutions of China, including the Communist Party and its most important governing bodies—and almost every other major government entity—as well as the educational, business, and cultural institutions of the country. Modern versions of the gender binary in China are in part the product of male leaders implacably reasserting male entitlement everywhere they can. It’s more complicated than that, of course, but men being in charge of everything in China is not inconsequential.

HOLD UP HALF THE SKY, OR, CRY IN YOUR BMW

Yet gender differentiation has not just taken the form of women losing rights and influence to men in post-Reform China. The literacy rate for women as well as for men went from 20 percent in 1949 to 66 percent in 1982 at the close of the Cultural Revolution. For youths, the literacy rate was 89 percent at the end of that period. Successful literacy campaigns provided a foundation for later dramatic transformations in higher education in China. Women raised their sights, and men were compelled to confront, both ideologically and in actual fact, the reality of women improving their prospects and working alongside them in field after field. In terms of educational achievements, women have maintained these advances.8

In other words, women have lost ground in some ways in post-Reform China, but they have maintained their progress and advanced in other respects. And this contradictory situation highlights the issue of nature and culture and gender relations: To what extent was the Maoist era, or at least the ideas espoused around gender equality, if not the actual lived circumstances, of that era, a cruel illusion, a horrific attempt to change men’s and women’s intractable natures? If biology is everything, then what we have witnessed since the 1970s is not so much a reversion to an unjust past as a resuscitation of predictably binary conditions, a reaffirmation that patriarchy as it has existed over the millennia corresponds to our inborn human male and female qualities. If biology does not rule gender roles, then are China’s post-Reform efforts to put women back into legally sanctioned, subservient positions traceable instead to social struggles, and to different core understandings about gender roles dictated by culture? Maoism called for gender equality, but it certainly never eradicated deep beliefs in gender differences, or, therefore, enduring skepticism about the feasibility of achieving this objective.

Perhaps reflecting such sensibilities, scholarship on gender in China since the 1980s has produced mountains of books and articles documenting the rise of a new managerial class of men, both in government and business. A good portion of this work has focused on the more lurid aspects of these activities, especially the “entertaining” that new elite and entrepreneurial men must carry out to massage relationships and seal deals. From bars and restaurants to karaoke and sex, every researcher worth his or her salt has come back from the fieldwork front with sordid stories, indecent images, and narrowly escaped escapades that could compromise all but the most objective of observers.9

The upsurge in male bonding rituals found in karaoke bars in China means recently minted men in business suits with wads of renminbi to spend on whiskey, women, and other diversions. Anthropologist Tiantian Zheng calls the karaoke bar scene “men’s triumph over women,” a setting that “prepares men for triumph in the market world.” The larger context for the postsocialist developments she describes is that it’s “not just about a refeminization of women, but… also, perhaps even more so, about the recovery of masculinity.” What it’s being recovered from are the days of the Cultural Revolution when men were formally expected to share with women, not dictate to them, just as much in the home as in society more broadly.10

A widely discussed aspect of this post-Reform backlash entails endorsement or disapproval of men’s extramarital sexual escapades—or simply resignation to these affairs. “Men have girlfriends,” a friend informed me. “Well, not my husband,” she hastened to add. “But others.” There are names for these girlfriends: they are called the Second Wife, or the Little Third, and the fact that such language has come rapidly back into the mainstream of daily conversations in China suggests that it is a widespread experience, and, of course, it is always married men dating women other than their legal wives. The common expectation is that men, especially those in power, will have mistresses—and that women in power would never have lovers on the side—and the common understanding of it is that men’s bodily needs were unnaturally repressed in pre-Reform China, and now can be given renewed validation.11

A corollary of the declaration that men need mistresses is the idea that uppity women are a problem. Men sometimes castigate the “Three-High Woman”: a woman with higher education, higher income, and higher age—and therefore higher expectations. Three-High Women cannot be satisfied with the things that made their mothers happy—but they should be, according to what appears to be a growing backlash among men against women’s educational and career accomplishments.

Nor is it only men who express the belief that the greater heights of society should be reserved for them. Some women, too, have quite publicly promoted the idea that what modern women want is to be maintained and pampered by modern men. In one famous incident, on a TV dating show called If You Are the One, a young man asked a young woman if she would be willing to ride on his bicycle for a date. Her notorious reply has been retold in China ever since: “I would rather cry in a BMW than smile on a bike.” She would not be satisfied with a man unless he could indulge her every whim. For these women, for whom marriage is no longer as much an expedient with potential for romance and pleasure as an individualistic quest to meet a standard dictated by idealized gender roles, romance means little if you can’t advance your material prospects. It is especially the man’s role to provide a high standard of living, and if that comes with mistresses, it may be regrettable, but it’s understandable if one believes that men need many outlets for their sexual impulses. That, too, fits the gender stereotype.12

There are contradictory pulls on young men and women in China. Some of these pulls come from parents, who have certain hopes and desires for their sons and daughters. Others come from government proclamations and policies, which can influence and constrain how people view these issues and the actions they take. Official edicts in China now rest more than anything on the notion that people must accept (and revert to) their gendered natures, thus rejecting much that seemed achievable during the Maoist era in terms of putting women and men on an equal footing. This stance contributes further to gender confusion and the erosion of gender equality. At the same time, pulls can come from unexpected directions: for example, some women refuse to accede to these reinvigorated patriarchal norms. If this contingent were to grow, it could have direct implications for ideas about men and masculinities and challenge beliefs about maleness in China that are based on popular but fallacious notions about the gender binary.

The bottom line is that gender confusion and gender renegotiation are playing out in particular ways in contemporary China in a tug-of-war between acceptance and rejection of gendered stereotypes. Do men and women have to be a certain way, or can we try to change them? Given everything else happening in Chinese society over recent decades, the renewed emphasis on male-female differences could only have been rooted in language that has the air of modernity. By looking at particular examples of the modernization of China’s gendered bodies and souls, we can gain fresh insights about the extent to which the increasingly conservative gender trends in that country reflect self-fulfilling prophecies about the nature of masculinity—not just for China, but for everyone.

MEETING AT THE SHANGHAI BLIND DATE CORNER

She’s not originally from Shanghai but has residence papers. She was born in 1982, stands about 5’5”, has a Master’s degree, and has never been married. She has a good moral character and an elegant beauty. And she has her own place to live. On the flyer her parents have posted describing her virtues at Shanghai’s Blind Date Corner, we learn that she is earnestly seeking a man who is around 5’9”, no more than five years older than she is, someone who is flexible as to where he lives and is willing to buy a home with her. There is no name on the flyer, just a cellphone number and the surname of a matchmaker for interested parties who wish to make contact.

Who might make that phone call? Most likely, it will be a mother or father with a son whom they are seeking to connect with a suitable young woman. And, quite possibly, neither the young woman in question nor the young man has advance knowledge that these potential connections are in the offing.

The parents in this scenario are in their fifties or sixties and come from a generation that only partially benefited from the reforms in China after 1979. Perhaps one or the other was laid off as privatization ran roughshod through state enterprises, and the Iron Rice Bowl of job security was no longer protected. These parents are also from the first generation to have China’s one-child policy imposed on their bedroom. And there’s a good chance that either the mother or the father, or both, migrated to Shanghai after the reforms began, part of a gigantic “floating population” of 250 million migrants from the countryside to China’s cities in the 1980s and 1990s.

And now these parents find themselves separated from their village or town community, approaching old age, and left to their own devices far more than the parents from earlier generations would have been at the same age. They are reasonably growing worried about what will become of them. As isolated elders with limited access to resources, to whom will they be able to turn for assistance and comfort in their later years? In urban China in the 2010s, social safety nets were tied to residence permits (the so-called hukou system), and as tens of millions of migrants from the countryside did not have permission to be in the cities (even if gainfully employed), levels of social precarity for many elders became extreme. Finding a suitable spouse for a daughter or son becomes a higher priority with each passing year, for with a son-in-law comes greater potential financial stability, and with a daughter-in-law come grandchildren and the continuity of the family line. Despite the economic boom times in post-Reform China, the bottom has fallen out of life for many in the middle and lower classes. They are desperate to find a solution to their children’s singleton status, and they find themselves reverting to the most basic, binary calculations of maleness and femaleness to try to resolve the conundrum.13

In Shanghai and in other large cities, including Beijing and Nanjing, such “Blind Date Corners” began to spring up around 2005. Aging parents and modern versions of matchmakers are the main attractions at these hubs; few children show their faces. There are certainly more parents than anyone else: they stand and sit along walkways and under trees, awaiting another parent’s interest in their child’s virtues. The flyers, pinned to upturned umbrellas lined up along the walkways, announce their children’s best qualities. For daughters, as often as not, this is beauty; for a son, it is actual or potential earning power.14

There is a protocol to what information is shared on the flyers, how it’s presented, and what is kept back until further contact is established. Some of the flyers look professional, complete with QR codes; others are written in longhand and include drawings, or even cross-outs and grammatical slips. They make for an endless and dizzying array stretching in every direction throughout the park. How a flyer appears is less important than its content. Matchmaker Wang told me she takes pride in handwriting flyers for her clients because she thinks passersby will appreciate the personal touch. “I really know these people,” she says. Overhearing us, another matchmaker smirked and needled her: “Isn’t it because you don’t know how to use a computer?” she asked.

Especially on nice days, thousands of parents jostle for space, trying to score a better position in the crowd. It’s a very pushy place, this Blind Date Corner, and certainly not a relaxed, genial space for idle banter about romance. Even when it’s raining, or miserably blustery, or humidly suffocating, mothers and fathers shuffle along, sneaking a peak at flyer after flyer. While some might find the peddling of a son or daughter brazen, for others this is the most important obligation that parents have to their child.

They have been thrown into a precarious situation. In the big cities, it is not so easy to ensure the continuity of the family line. Nevertheless, they must succeed in helping their children find spouses, and in order to do this they must find some way of presenting their sons and daughters to the world. It was under this kind of pressure that the Blind Date Corners became popular. With brutal simplicity, even though they themselves come from a generation that epitomized gender equality and sameness (in clothing, employment, wages, and aspirations), today’s aging Chinese parents tend to accentuate the most stereotypically masculine and feminine attributes, ones rooted in what they think might, just might, be preset in men’s and women’s bodies.

These are the parents who lived through the Cultural Revolution of 1966 through 1976, when androgyny was the tacit code of conduct, and one way they can put those days behind them is to maintain that we really should not expect the same things of men and women. The unambiguous reassertion of the patriarchy is a key feature of the post-Reform period. With it has come a re-forming of the gender binary. Prior to the twentieth century in China, kinship categories largely defined gender roles: women’s identities, for example, were circumscribed by their relationships to fathers, brothers, and husbands. Biological ideas about gender binaries filtered in with scientific thinking, however, and as these notions gained ground, earlier ideas subsuming women into overtly male cosmologies began to ebb. After 1949, Maoism took on a more virulently anti-feminine guise—one reason why the backlash today includes a reassertion of feminine looks and manners.15

MODERN MATCHMAKERS

Parents at the Blind Date Corner can go it alone, displaying their umbrellas in hopes of generating interest from other do-it-yourself parents, or they can approach a matchmaker and pony up ¥500 (around US$75 in 2015), in the case of a daughter, or ¥100 (or as little as ¥50) for a son. In return, the matchmaker will post a flyer advertising that daughter or son for up to six months. Matchmakers used to openly set up card tables and chairs around the park; in more recent years they have had to be more discreet, as police sometimes attempt to run them off. In any case, going through a matchmaker still has advantages. A matchmaker might have years of experience in successfully finding mates for their clients’ children (or so it’s claimed), and may have a catalog of single young women and men to choose from (although they may or may not be real singles). The matchmakers, sitting on stools scattered along the walkways of the park, patiently going through their thick binders and iPad lists with parents with a self-assured demeanor, exude a curious blend of skills, part marriage broker and part electronic cupid.16

You might expect that the children on the flyers would resent these direct intrusions into what should be a subjective and private concern. And you might not be wrong. But to better understand the perspective of these young people, it helps to know a few additional facts.

Most importantly, no one—not the daughters, the sons, the mothers, the fathers, or the matchmakers themselves—wants any of this process to be called traditional. Everyone in Blind Date Corner will tell you that what is happening there is an emphatically modern event. In China, as everywhere else, what exactly it means to be modern sparks debate. People who spit, clean their noses, and shout in the public street are not modern in anyone’s eyes. Yet, in contrast to Europe and the United States, religious devotion is often considered especially enlightened and worldly. Women working outside the home are viewed as urbane and progressive for some, but for others, the quintessential nouveau riche is the wife in the new capitalist supercaste, whose wealth and privilege permit her the luxury of not working for money.

Blind Date Corner is as modern as mass migration, as avant-garde as working seventy hours in an office every week. Far from conjuring the image of traditional matchmaker, the very modern realities of migration to the city and employment in office work are the most common explanations for why young people might be grateful to their parents and others who make these initial overtures with the promise of future romance, marriage, and children. They, too, want to embark on that stage of life before it’s too late.

Almost every adult daughter and son in Shanghai is also acutely aware of being a single child. They were born after the one-child policy went into effect, and particularly after the state started applying the policy with greater force in urban areas beginning in the early 1980s. This generation of young people is by far the best-educated, highest-earning, and most individually ambitious group to come of age in China’s long history. But it is also in some ways said to be the loneliest. Matchmaker Yang spoke to me about the crush for eligible bachelors and bachelorettes that was generated by “economic development” and “market development.” To use outdated terminology, or discuss how contemporary matchmaking was related to older practices, was, he insisted, the kiss of death for business. The label “traditional” was anathema for youths caught up in the swirl of urban life.

In response to modern dating and mating dilemmas there are also new television shows in China with a large and loyal viewership. These modern spectacles include If You Are the One, One Out of a Hundred, or Cream of the Crop, along with Luo Ji’s Thinking, with its famous moderator, Fatso Luo. As in other countries, Internet dating sites have proliferated in China, beginning in the 2000s. But parents can’t go on TV for their kids, and it’s creepy when they go online for them. As the Blind Date Corner matchmakers insist, nothing beats face-to-face talks, which, though taking place in a public park, seem more private. When parents beseech matchmakers to find a partner for their child, you hear anxious voices as they relate something of the child’s nature and top selling points: “She’s so pretty and gentle,” for example, or “He’s responsible and has a good car.” In their intonations it’s hard to miss the naturalization of emerging gender differences.17

At Blind Date Corner you receive a personal touch that’s just not available online or on television. There are even special zones within People’s Park where you can look for matches who have specific qualities. For example, there are places for Chinese prospects who have lived in other countries, such as Australia or Japan, and have returned and are open to foreigners who might be looking for a Chinese soulmate. They are all grouped under national flags in the “Overseas Corner.” Foreign imports, in the form of people or ideas about manliness and femininity, add cachet and conditions to the search for a wife or husband.18

My favorite among the marriage mavens is Matchmaker Zhu. We’ve been friends since I spotted him wearing a red Che Guevara badge on his green People’s Liberation Army cap in 2013—purely a fashion statement, he claimed. The niche that Zhu Wenbin has developed is to keep his clientele on both sides of the equation strictly Shanghainese, although he will offer advice to any and all who are looking for a significant other for their child. One day I asked him, “What do you look for when people come up, other than whether they are from Shanghai or among the recent arrivals?” Matchmaker Zhu misunderstood my question and thought I was asking what people should look like when they meet prospective mates: “Women should wear as little as possible, and show as much skin as possible. Guys should wear something business casual. Show their financial worth.”

My friend Zhu had been no Cultural Revolution zealot, but even for him advertising women by their looks and men by their wallets in such a blatant way was a very modern twist in the matchmaking game. It was based on a salesman’s knowledge of his market, which in turn was based on relapsed thinking about essential gender differences.

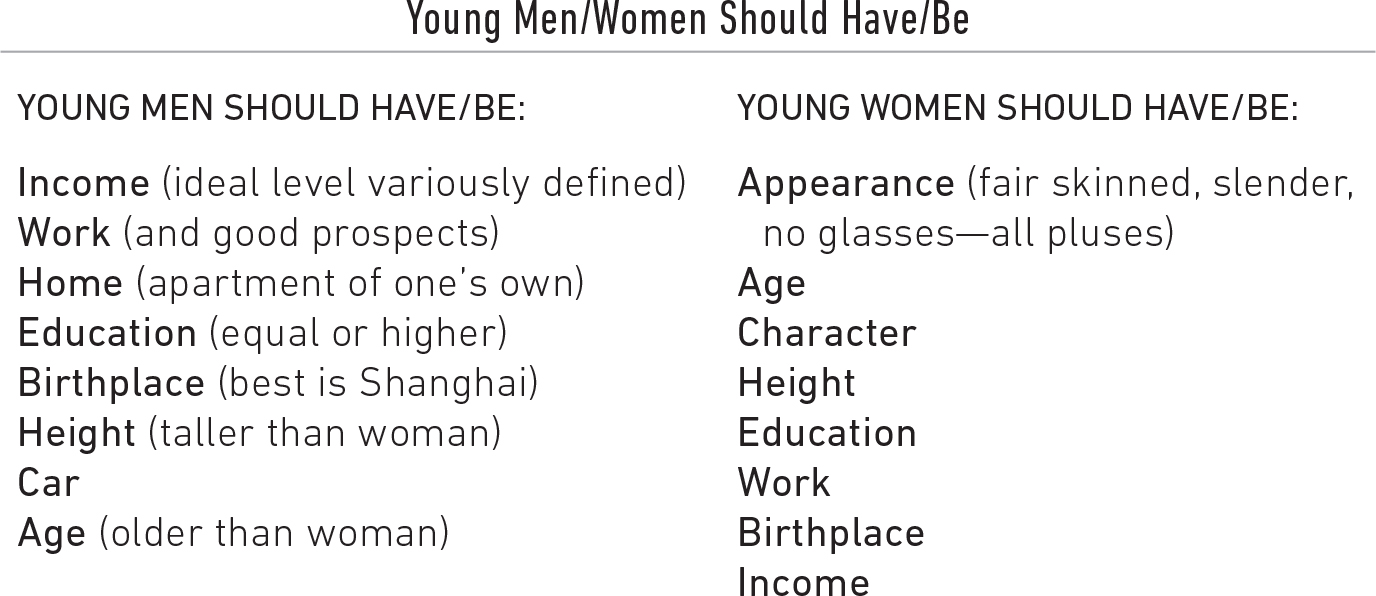

At the Shanghai Blind Date Corner, the intellectual and career accomplishments of daughters are generally included on their flyers, along with their physical attractiveness. Men’s flyers list their height, professional trajectory, and whether they can already provide housing, along with a brief statement, written by the matchmaker or parents, vouching for their worthiness. Although some flyers at the Blind Date Corner about young women list housing as one of their positive features, it is far more likely that this information is provided for young men. The parents of young men offer the parents of young women a permanent place for their daughter to live as an incentive, and the parents of young women look for this capacity in young men. Matchmaker Zhu helped me compile a rough guide for judging the marriageability of young men and women, shown in Table 3.

One question that parents of daughters ask with surprising frequency, Zhu says, is, “Does he get into traffic when he goes to work?” They want to determine how far he lives from work and how long he will be gone on a regular basis. On a subtler level, another matchmaker, named Ling, described the ideal young man as someone who exuded confidence and elegance, someone who was more than just a pretty boy. For a young woman, even better than possessing just the generic quality of beauty, it was important to be delicate in manner and proper in conduct.19

Matchmakers are helping parents take the first steps not only toward marriage for their children but also toward housing and grandchildren. But parents were not necessarily out to lock their children into prearranged relationships. They merely collect the information, rather than forcing their grown children to do anything with the information they collect. “They’re too busy,” was the refrain on many lips in the Blind Date Corner discussions. “They don’t have time to find loved ones.” All the parents were doing was getting some names. Their children would make the final decision. Think of all the stress the children were being spared: they wouldn’t have to start from scratch.

Perhaps these parents have too much time on their hands. Possibly a large percentage of them are retirees, and these gatherings have more to do with their own social lives than with the marital futures of their offspring. But without a doubt, parents who are panicked about their children’s marriage options are overrepresented at the People’s Park. It might even look like a survival-of-the-fittest moment when every Saturday and Sunday, Blind Date Corner becomes the site of earnest competition by proxy: parents armed with flyers advertising the physical, financial, and temperamental virtues of their progeny in a public declaration that they will do anything they have to in order to find a mate for their only child. As time passes without making a match, parents dig deeper into their storehouse of enticements, and these invariably embellish the most feminine or masculine attributes of their children. Despair breeds what they see as gender orthodoxy.

Despite decades of achievements in gender equality, both in China and worldwide, there is nonetheless a powerful sentiment that sooner or later men and women will revert back to their binary states. This is how people can explain other conservative pulls in China, too, like the crisis of the leftover women.

IS YOUR DAUGHTER A LEFTOVER WOMAN?

In addition to the comments in 2012 by China’s president, Xi Jinping, that party members needed to man up, mentioned in Chapter 5, in October 2013 Xi urged “the majority of women” in China to double down on their child-rearing responsibilities. It was their unique duty, he said, to “educate children” and build “family virtues.” Chatroom comments erupted over the clear implication that men did not need to shoulder responsibility for these duties. Some called it not just old fashioned but “defective reasoning”; others agreed that it was a “retrogression to the nineteenth century.” It would be easy to dismiss the comments of Chinese leaders as antediluvian and ideological were it not for the explicit justification of their comments by appeal to the need to accept what is inevitable for men in comparison to women.20

Here’s the thing about those flyers from the Shanghai Blind Date Corner: although it is common knowledge that in China men outnumber women in the overall population because of selective abortions of female fetuses during the one-child era, among other reasons, the Blind Date Corner operates because more women than men are looking for mates. Or, more precisely, because there are more parents looking for husbands for their daughters than there are looking for wives for their sons.

Although from the Western media you might think a key social problem in China is what to do with all the extra men who cannot find a spouse, in certain places, like Shanghai, the problem is just the opposite. I gathered a random sampling of thousands of flyers posted at the Shanghai Blind Date Corner and found the following:

Only 35 percent of the flyers overall were for young men.

Only 35 percent of the flyers overall were for young men.

For flyers reporting youths’ salaries as “low,” 67 percent were for young men.

For flyers reporting youths’ salaries as “low,” 67 percent were for young men.

For flyers reporting youths’ salaries as “high,” 13 percent were for young men.

For flyers reporting youths’ salaries as “high,” 13 percent were for young men.

For flyers reporting education levels beyond an undergraduate degrees, 29 percent were for young men.21

For flyers reporting education levels beyond an undergraduate degrees, 29 percent were for young men.21

In a reversal from overall demographic trends (there are indeed more men for fewer women, especially in the countryside), at the Blind Date Corner there are more flyers for women than there are for men, and the women tend to be better off financially and better educated. In China as elsewhere, women, on average, want to “marry up,” and men tend to “marry down.” That leaves men at the bottom and women at the top coming up short more often than those in the middle. Almost 26 percent of urban women in China had been to college as of 2010, and in fact women outnumbered men in university programs that year. The Chinese government was quick on the case to address this very new, very contemporary predicament, and directly launched campaigns to correct it, sounding an alarm among the broader public that women were educating and pricing themselves out of the marriage market.

In 2007, a couple of years after the Shanghai Blind Date Corner began to attract customers, the all-important All-China Women’s Federation issued a declaration on the “leftover woman,” defined as an unmarried woman over the age of twenty-seven. The federation, decrying the reticence of young, successful women to marry, called for a public effort to turn this situation around, and quickly. It also began organizing matchmaking events for unmarried young women in factories around China.22

It might be tempting to write off the expression “leftover woman” as hyperbole—or even as government verbiage, given the federation’s close association with the Communist Party—but the term tapped directly into mounting concerns on the part of parents of single daughters who feared their offspring could end up childless. The label exploited a deep vein of conservative thinking about the character and responsibilities of daughters versus sons. By specifying an age, and implying that the childbearing years were fast falling away, the federation’s call to duty for daughters to produce grandchildren was unambiguous.

Before we attribute too much sinister intent to the Chinese authorities, we must look at the real starting point for all the fuss. Or, if not the starting point, at least the first time the term “leftover woman” appeared in print: as it turns out, it was no less erudite a publication than the Chinese edition of Cosmopolitan magazine. In its February 2006 issue, Cosmo ran an article called “Welcome to the Age of the Leftover Woman,” and subsequently, several commentators have attributed the coinage of the phrase to the then editor-in-chief of Chinese Cosmo, Xu Wei. In China, as in the United States, if you want to know what is au courant in the world of gender and sexuality, look no further than the pages of Cosmo.23

Readers of the article were treated to curious claims on the roadmap leading to leftover womanhood, reflecting the intimate sociology and psychology of changing times and gender relations in post-Reform China. Soon, the “leftover woman” had made her way into newspapers and onto TV dating-game shows and sitcoms, often with a smirk, but never without a bite. Matchmaker Wang, in her sixties, with a long wall of flyers behind her, was zealous in her certainty that the leftover woman was a major challenge for contemporary Chinese society. Grinning, she goaded rhetorically, “Why is it a problem? Isn’t it obvious? Why, if they don’t get married by a certain age, they certainly won’t be able to have babies!”

Thus was the biological clock invoked. Still, there was more at stake than mere disappearing ova. The fact was that matchmakers made catchy use of the fear of the leftover woman, insisting to passersby in People’s Park that unmarried women go against nature. In many respects it represented the chickens coming home to roost on China’s one-child policy, which had been launched at the tail end of the 1970s. The policy left parents feeling an unease sometimes verging on desperation. They wanted their daughter to be married. They wanted a son-in-law who could help take care of them in their old age. They wanted a grandchild. And they wanted the sanctity of marriage to be defended from the new habits of young couples living together “outside the law” and in so-called trial marriages. Relative to other countries in the region, China’s marriage rates were high in the early 2000s: in 2010, 81 percent of women and 75 percent of men in China were married. And yet the fears persisted.24

In 2010, three years after the official announcement of the leftover woman problem, a study by the Marriage and Family Research Association, which is affiliated with the All-China Women’s Federation, published the results a survey of over 30,000 people nationwide regarding attitudes toward love and marriage.25 Of course, like political polling, surveys often not only reflect public opinion but also shape it. Nonetheless, the 2010 study is noteworthy, not least because it delineated four subcategories of leftover women (each representing an arcane play on words). Keep in mind that the average age of first marriage for women in China in 2010 was around twenty-five years old overall, and it was twenty-six and a half for women in Shanghai:

1. Women aged twenty-five to twenty-seven: “Leftover/Saintly Fighters,” i.e., women who still have the courage to fight for a partner

2. Women twenty-eight to thirty: “Leftovers Who Must Win,” i.e., women whose chances for marriage are dwindling and who barely have enough time for courtship

3. Women thirty-one to thirty-five: “Buddha’s Leftovers from Fighting the Wars,” i.e., women who have won the career wars but lost the marriage wars

4. Women thirty-five and older: “Great Leftover/Saint, Equal of Heaven,” i.e., women who have it all—except for a husband26

The word raised constantly by parents, matchmakers, government proclamations, and on television and in print media, or on the Internet and on the radio, is “picky,” as in, “Women today are too picky.”27

PICKY WOMEN GET LEFT OVER

One man I interviewed, Matchmaker Yang, shared a variation on the picky theme, saying, “Women’s expectations are too high.” He thought this was directly linked to the fact that children in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries had so much more given to them than their parents had, and much less than their grandparents ever had; as a consequence of these better living conditions they thought they could be choosier in every part of their lives, including finding a marriage partner. Daughters had “too many requirements,” starting with the husband’s financial prospects, Yang lamented, adding, “Most of the time they are being unrealistic.”28

Another matchmaker, named Chen, echoed these sentiments, explaining that the problem was that young women were too demanding when it came to young men. She insisted, “Their standards are too high.” She urged young men to recognize that they have requirements that are just as important as young women’s, and that they should not be so intimidated by the women that they are scared off from making contact with them and seeing where things could lead. However, there were limits, she counseled. As an example she pointed to the flyer of one young woman who listed, as one of her requirements, “serious inquiries only.”29

Not coincidentally, Serious Inquiries Only is the name of a well-known television dating show. The phrase indicated to Matchmaker Wang that there was no point in even contacting this young woman “if you are even one centimeter shorter than her requirement.”

Young women in modern China have been encouraged both to expand their life goals and to limit their goals and desires: to get a PhD, but not if it will interfere with getting married and having children; to be independent, but to find a husband who can provide an apartment for you; to have a marriage of equals, but to accept that his name alone will be on the property.

The language used in the 2010s in China to describe gender relationships—including in jest—reflected and reinforced particular, unspoken, and sometimes unconscious cultural assumptions and frameworks about the need to accept certain biological basics about maleness and femaleness. In this way, daily conversations about men and women could seem to be more an acknowledgment of unchangeable realities than an actual politically conservative campaign against women.

Daughters and sons are marketed in China by appeal to formulaic gender qualities, and the leftover women scare is fueled by anatomical reasoning. Beliefs in male-female differences are nothing new in China, but the reassertion of modern versions of the gender binary to replace official Maoist egalitarianism has required renewed emphasis on gendered biologies. No wonder a gender joke became widely told in Shanghai at this time: Do you know that there are not two but three genders in China? Men, yes. Women, yes. And the third? Women with PhDs! It didn’t take long before a fourth gender was added: men married to women with PhDs.

It is unlikely that Chinese women will be returning their PhDs for sewing class certificates anytime soon. Many women are resisting attempts to strengthen patriarchal norms throughout Chinese society, but many others are trying to make the best of the situation. Men in China, as elsewhere, will either seek to benefit from male privilege or seek to break from these patterns. But to the extent that men’s biological destinies—and primordial needs and presumed superiorities—are being reinforced in everyday life in China, Mexico, and the United States, the danger of naturalizing the benefits of gender birthright persists. Yet, as always, there will also be powerful countervailing currents among women and men for renegotiating maleness and masculinity. Demands for gender parity can make an equal claim to biology, in the form of new branches of the science, such as epigenetics.