10

Hell’s Outpost

“There was just one thin sheet of sandpaper between Yuma and Hell.” | SARAH BOWMAN

Mark Twain called it “the hottest place on earth.”1 A resident lieutenant considered it cool there if the temperature held at one hundred degrees. And legend had it that a soldier who died there had gone to hell and found it so cold by comparison that he returned for blankets.

But in 1856, Fort Yuma was hellish for reasons beyond the heat. It was bedeviled by blinding dust storms and prone to Indian attacks. The barracks were plagued with ants, gnats, and, when the river was high, mosquitoes, and the toilets were open trenches heaped with dirt and lime to squelch the stench. The camp’s poorly paid soldiers, who found scorpions in their shoes in the morning and bats in their tents at night, played host to errant bandits and trappers, missionaries and prospectors, scientists and settlers from across the nation, some of whom stumbled into the grounds half-starved, having roasted their own pack mules to survive. Apart from a handful of officers’ wives, the only local women were prostitutes, managed by a towering, pistol-packing madam known as “The Great Western.” This would be Olive’s first taste of civilization after five years among Indians.

Though it had been closed in June of 1851, just after Lorenzo had left for San Francisco, the fort had reopened in early 1852 with better supplies and more soldiers. Its purpose — to protect emigrants from Indians (as well as from their own recklessness) — remained the same. In that respect, the 1851 Oatman tragedy had marked a spectacular failure. But if the legendary episode was a black mark in the fort’s annals, Olive’s homecoming, five years to the month after her disappearance, was its redemption.

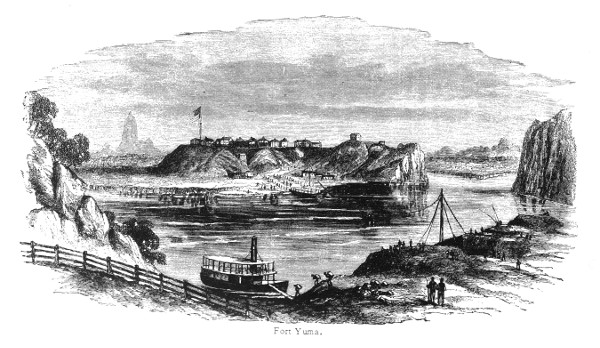

FIG. 13. Fort Yuma, seen from the Arizona side of the Colorado River in 1864. Sarah Bowman (nicknamed “The Great Western”) said, “There was just one thin sheet of sandpaper between Yuma and Hell.” Illustration by J. Ross Browne.

At about 9:00 a.m. on the last day of February, Grinnell learned from a Quechan messenger that Olive and her party had arrived and were waiting for him across the river. He hurried down to the crossing, sped across in Jaeger’s ferry, and stepped off to see that Olive already had an audience: a collection of local Quechan Indians, seized with curiosity, had converged on the riverbank with their trademark quivers on their backs, knifes at their hips, and rings in their ears and noses. Wearing only a bark skirt, Olive was sitting on the ground, hiding her face in her hands. Tanned, tattooed, and painted, she was all but unrecognizable as a nineteen-year-old white woman. The straight line of a vertical blue tattoo ascended each of her bare upper arms. Her naturally light-brown hair was as dark as a Mohave’s, dyed black with the gum of the mesquite tree.2 When Grinnell approached her, she cried quietly into her hands but let him lead her to the water, where she washed and changed into the calico dress an officer’s wife had sent from the fort. Now, free of face paint and hair dye, and wearing Anglo garb, she was ready — or at least dressed — for her return.

Grinnell called a meeting in his quarters then climbed into a boat with Olive, Musk Melon, Topeka, and Francisco to cross the river. The Quechans swam furiously behind them, intent on witnessing the full spectacle of Olive’s ransom. As she ascended the jagged hill to the fort, she was greeted with the shouts and cheers of soldiers and the whoops of local Quechans who had gathered to see the white captive everyone had given up for dead. Cannons boomed. Flags snapped in the wind. And Olive had no idea why she was being applauded. Her anxiety was surely paralyzing: she had left behind a loving, familiar community and was entering a foreign land where — as far as she knew — she had no friends or family, and no idea of where she would live or who would care for her. Francisco and Topeka would return to their respective tribes once she was delivered, and Musk Melon would disappear to spend the coming weeks with Quechans south of Fort Yuma.

Olive was ushered into Grinnell’s cabin and seated for a formal interview with Commander Burke. Timid, but also eager to please, she answered questions she clearly did not comprehend with a gentle nod. Burke, a scrupulous interrogator, was careful to record only responses to questions he was certain she understood, even testing her comprehension as they talked. “In answering questions purposely [framed] directly opposite,” he wrote in his report, “she invariably says ‘Yes’ to both.”

She gave her name as “Olivino,” recalled her father’s surname as “Oatman” and said she’d had six siblings, mentioning Lucy and Lorenzo by name. She identified her abductors as Apaches. Asked if they had treated her well, she said, “No. They whipped me.” In response to the same question about the Mohaves, she “seemed pleased,” noted Burke, and answered, “Very well.”

Though she recited the general plot of the massacre, her slippery grasp of significant details indicated how far her pioneer past had receded in her memory. She remembered being eleven instead of fourteen when she was captured, and wrongly stated that Lucy’s husband (she was not married) had been killed in the ordeal. Still, she outlined the basic contours of her captivity — one year with the Yavapais, more with the Mohaves — and recalled that she had been traded for blankets, beads, and two horses. She confirmed that she had never left the Mohaves for any reason (even, as Burke probably wanted to know, when the Whipple party had lingered in the Mohave Valley). After Mary Ann’s death, she said, “there was not much to eat, but I helped them, and got used to it, and got along with them.” “They saved my life,” she said.

Burke asked, “What did they give you to eat?”

“Wheat, pumpkins, and fish.”

“Mesquite also?”

Olive laughed and answered, “Yes,” amused, possibly because gathering Mesquite beans was an arduous task — they were not just handed out.3

When Burke finally told her that Lorenzo was alive, she was so stunned that she had to lie down and appeared, for a while, to be unconscious. Burke explained how Lorenzo had escaped and asked Olive whether she could remember how he looked. She gestured that he resembled her, which he did. The commander told her he would notify her brother, now in Los Angeles, who would come see her.

That night, Burke sent word of Olive’s arrival to the Los Angeles Star, but the news took a week to travel through the desert and make it into print, and even longer to land in Lorenzo’s hands. As the news of Olive’s return began to trickle out, the press and the public rallied to her cause. The San Francisco Herald ran a story about the “young and beautiful American girl,” saying she would be cared for at Fort Yuma “until relatives or friends may come forward to relieve the poor girl from her present dependent position” and encouraging philanthropic women to take her in or get her admitted to the “Orphan Asylum.”4 The story, copied by the Daily Alta California, the Evening Bulletin, and the California Chronicle, swept across the country, appearing in newspapers in nine other states, from Iowa and Wisconsin to Georgia and New York.

The San Francisco Sisters of Mercy responded by offering, through the Herald, to take Olive. Her Indian leanings were already a concern: the paper hoped someone would try to “wean her from all savage tastes or desire to return to Indian life.”5

The Collins family, who had traveled with the Oatman train as far as Tucson, convinced a county judge to petition Burke to send her to their home in San Diego, where, the Daily Alta projected, “she will shortly be able to resume the position in society which five years of savage bondage has deprived her.”6 And the state legislature passed a bill to grant her fifteen hundred dollars, but when the governor either failed or refused to sign it within ten days, it expired. Knowing none of this, Olive waited for the next two weeks in limbo. For their part, the officers at Fort Yuma pooled their money in a fund for her.

Olive’s stay at Fort Yuma must have been unimaginably weird. Though the newspapers later said she was cared for by the wife of Lt. Reuben Twist, her guardian angel was a much earthier character: an Amazonian redhead named Sarah Bowman who ran a combination mess kitchen, boarding house, and brothel across the river. An officer’s wife, evidently, was a more respectable caretaker to assign to Olive — at least in print.

A six-foot-tall, forty-four-year-old Irish-American from the South, Bowman was outsized in every way: nicknamed “The Great Western” after the largest of the first steamships to cross the Atlantic in 1838, she had also been dubbed “the heroine of Fort Brown” during the Mexican-American War because she had cared and cooked for soldiers throughout a seven-day siege during which Mexican cannonballs rained down around her.7 While other women hid in a shelter sewing sandbags to shore up the fort, she had rushed around with bean soup and bandages, feeding and nursing soldiers even as bullets pierced her hat and punctured her bread tray. When the United States won the battle, Bowman was celebrated in newspapers across the country for her calm, courage, and competence. Years later she received a full military funeral.

One soldier found Bowman “modest and womanly notwithstanding her great size.” He described her crimson velvet dress, riding skirt, and gold-laced cap, an outfit topped off with pistols and a rifle. “She reminds me of Joan of Arc and the days of chivalry,” he said. A man who knew her when she was working as one of the first madams in Texas observed that even the Indians “seemed to hold her in perfect awe, and had a superstition that she was a supernatural being.”8

Though she was illiterate (if bilingual), Bowman was an enterprising and successful businesswoman. She had worked her way west, kitchen by kitchen, and when the opportunity arose, bedroom by bedroom, until she landed at Fort Yuma, where she now had a full staff and lived with her partner, an upholsterer from Germany. “Among her good qualities,” wrote one lieutenant, “she is an admirable ‘pimp.’ She used to be a splendid looking woman and has done ‘good service,’ but she is too old for that now.”9

Bowman could be fierce and foulmouthed, but she was well liked — she had even won over the impossible Heintzelman, barring a few nights when his soldiers returned drunk from her house. She wore a scar on her cheek as souvenir of her service in the Mexican-American War (and claimed she killed the Mexican who cut her), but she was bighearted: she took in as many as five orphans at once, both Mexican and American, which is probably why Olive was put under her protection during at least part of her stay at Fort Yuma. In 1853 she had moved her entire operation across the river into Mexico to prevent her teenaged foster daughter, Nancy, from being hired as a servant to a lieutenant’s wife in San Diego.

Bowman’s unconventional nature — she was no Victorian lady —may have smoothed Olive’s transition back into white America. The Western, as she was called, had had a series of husbands (mostly younger) who, like Mohave spouses, were common law, and, like Olive, she was a survivor with little schooling and no known family. Her legendary maternal touch was no doubt a comfort to Olive, who had now lost two mothers. Likewise, Bowman became attached to Olive in the weeks they spent together and later honored her by taking a crew out to tend to the Oatman family’s perpetually disrupted grave. Olive ate and slept at Bowman’s (the officers’ mess was at the fort proper) and visited with the few military wives in residence, who tried to reacquaint her with the folkways of white women.

Still, Olive’s reentry was surely overwhelming. Few women followed their husbands to Yuma (Heintzelman, for one, had called the assignment “an outrage” and left his family in San Diego); consequently there was no female community beyond the brothel to speak of, and the camp was now populated with about 250 men.10 Because Bowman offered food, lodging, liquor, and women at her adobe house across the river, she controlled the social life of the region — such as it was. She arranged live-in mistresses for soldiers (“It costs almost nothing to keep a woman here. … In fact it is a matter of economy,” wrote one lieutenant11) and threw oyster dinners as well as more formal affairs, including Nancy’s wedding to a discharged sergeant from a company in New Mexico — which was followed by a party that went on all night and well into the next day. As a courtesy, Bowman invited two prostitutes to the reception so the men would have dance partners.

Sylvester Mowry, a sex-obsessed lieutenant who had fled Utah after a dangerous liaison with Brigham Young’s married daughter-in-law, described army life at Fort Yuma in a letter to a friend: “Our principal occupation at present is drilling, riding, ‘rogueing’ Squaws and drinking ale — the weather being too hot for whiskey.”

He elaborated, “We are surrounded by squaws all day long entirely naked except a little fringe of bark hardly covering their ‘alta dick.’ Hide is cheaper here than in any place I have ever been. A pound of beads costs $2.50 and you can ‘obtain’ fifteen or twenty squaws for a tender moment with it.”12

Mowry, who would become active in mining and politics as one of Arizona’s founding fathers, may have sensed the impending doom of the Colorado River tribes. He was the first to interview Olive after Burke, and unlike the newspaper reporters who wanted to know about her personal experiences among the Mohave, Mowry wanted to know about the Indians themselves — beyond their “alta dicks.” In a report called “Notes on the Indians of the Colorado,” which he compiled that March and submitted to the Smithsonian Institution, he provided, based partly on Olive’s descriptions, a brief taxonomy of the Upper Colorado River tribes, detailing their wars, spiritual beliefs, marriage practices, dialects, and hunting and farming traditions. Olive must have regained her English fairly quickly in order to supply the kind of detail Mowry attributes to her in his report — he quotes her saying that some Mohaves practiced a “promiscuous concubinage” that others considered reprehensible.13 She also betrayed an impressive knowledge of the surrounding tribes and their estimated populations. In a later report to the commissioner of Indian Affairs, he says Olive gave him “much information” about the Yavapais as well.14

At Fort Yuma, Olive was quickly immersed in a stagnant culture of military routine, where the soldiers’ only diversion from each other — sex — was crassly commercialized, and everyone (Olive included) was merely marking time at what was considered the worst army post in the West. Mowry wrote that “all [the] old officers advise the young ones to resign while they are young enough to do something else.”15 Those with low tolerance deserted. Those who stayed risked the wrath of angry Quechans whom the army had driven from their planting grounds along the Colorado.

The contrast between this benumbed lifestyle and what Olive had left behind was dramatic: she had never known a Mohave to trade sex for money. She had lived in a lovely valley bordered with willow and cottonwood trees, where her people delighted in swimming and sports, group dancing and storytelling. The debased physical conditions at the fort alone must have been appalling to her. To complicate matters, no one there spoke Mohave, so her transition back to English was achieved by total immersion.

Even Yuma’s one natural beauty was marred for Olive. Lieutenant Sweeny, who had called the region “about as ineligible a site for a fort as an ice-burg in the Atlantic,” conceded that Yuma nights were glorious. “The stars shine like loop-holes into the Heaven of heavens, and [the] moon like the home of calmness, purity and peace. But there is a never-ceasing hum of millions of insects, and the Colorado murmurs like an uneasy Titan, and shines, and whirls its red flood along, like a huge bronze serpent, whose glittering scales reflect the moonbeams.”16 Sweeny didn’t mention another source of evening light: the glow of Indian campfires that dotted the vast desert landscape, reminding Olive of her former home. A single pastime carried Olive through her early repatriation: given thread and fabric, she quickly remembered how to sew, and did so in a therapeutic frenzy.

Weeks after Olive’s ransom, on a sunny March day in El Monte, California, Lorenzo stood chopping wood — the latest of a series of menial jobs he’d taken since moving down from San Francisco — in a forest a few miles from where he was living with the Thompson family. At the sound of pounding hooves, he looked up to see his friend, Jesse Low, galloping through the woods with a newspaper under his arm. In Los Angeles Jesse had helped Lorenzo in his search for his sisters, where together they had published queries about the girls’ status. Near Yuma, the two had gone searching for them on horseback. Low arrived now with the final clue to the Oatman mystery. Without so much as a greeting, he handed Lorenzo the March 8 Star article announcing Olive’s return: “From Mr. Joseph Fort, of the Pacific Express Company, we learn that Miss Olive Oatman, who was taken prisoner by the Apaches in 1851 …has been rescued, and is now at Fort Yuma. Further particulars next week.”17

Lorenzo was floored. “I now thought I saw a realization,” he said, “in part, of my long cherished hopes. I saw no mention of Mary Ann, and at once concluded that the first report obtained by way of Fort Yuma …was probably sadly true, that but one was alive.”18 He jumped on a horse and rode straight to the Star offices on Main Street in Los Angeles for verification, where the editor showed him Burke’s letter asking that the news be printed “with a view that Miss Oatman’s friends may be aware of what has occurred.”19 Lorenzo borrowed money and horses from Low and took off for Fort Yuma, desperate to see his sister, yet afraid that there had been a mistake — that the report was wrong or the captive was not Olive; he had been disappointed so many times before.

Ten days later he and Olive were publicly reunited. By then, she had regained much of her English, which promptly failed her in the face of this momentous encounter. “For nearly one hour,” Olive said, “neither of us could speak a word — for the history, the most thrilling and unaccountable history of years was crowded into that hour.”20

Though whites, Mexicans, and Indians alike were said to be teary over the tender reunion, the ferryman L. J. F. Jaeger observed it without sentiment in his diary: “We had a warm day, and Oatman got in from Los Angeles also after his sister …and I went up to the fort with him …and she did not know him and he did not know her also, so much change in five years.”21 Lorenzo never commented on his reaction to Olive’s tattoo.

Most of the men Lorenzo had met at Fort Yuma, the site of his recovery, were gone: Heintzelman had returned to San Diego, Sweeny had moved on to other posts, Dr. Hewit, of course, had left with Lorenzo, and “Dr. Bugs” was now teaching in New York. Jaeger and Grinnell were perhaps the only familiar faces. The landscape had also changed: adobe buildings had sprung up in place of the brush tents that once served as officers’ quarters, and the hospital Hewit had battled Heintzelman to build was fully functional. A sutler had set up shop and soldiers now bought their provisions from him. Thanks to the Great Western, the town of Yuma, then called Colorado City, was sprouting on the opposite bank, though it had only about a dozen residents.

Lorenzo spent two days visiting with Olive, rehearsing the past and discussing the future, before taking her back to El Monte. The day they left on a Los Angeles–bound government wagon train, Musk Melon returned from the Indian settlement downriver where he had spent the past few weeks, in hopes of seeing Lorenzo. He arrived when the caravan was pulling out, and called to Olive, who was riding behind the train. When she dismounted to talk to him, Lorenzo grabbed a club and lunged at him.

“Don’t!” Olive exclaimed. “He’s a nice man. He took good care of me.” Her brother backed off, and when she introduced the two men, Lorenzo handed Musk Melon a box of crackers as a peace offering, which he accepted.

Olive turned to her friend, speaking Mohave. “This is the last I shall see of you,” she said. “I will tell all about the Mohave and how I lived with them.” They shook hands, and Musk Melon watched her disappear into the desert.22

Olive would have ample opportunity to tell the world about the tribe. Within a month she was a media darling. In the nascent California print world of the 1850s, fed by articles about phrenology and spiritualism, temperance and bloomers, Pacific Coast fog and the legal “admissibility of Chinese and Negro testimony” against whites, Olive presented a human interest epic with legs.23 She was often called beautiful. In this era before photojournalism, readers relied largely on verbal descriptions for their visual impressions of the white Indian. “The rescued lady is said to be very fine in appearance with agreeable manners, but has entirely forgotten her native language,” wrote the San Francisco Weekly Chronicle.24

“Her hands, wrists, and arms are largely developed,” observed the San Francisco Herald. “The hair of the young lady, [is] of light golden color, the Indians dyed it black — using the bark of the mesquite tree. … She is more fully developed than many girls of twenty.”25

The Star applauded her “lady-like deportment,” “pleasing manners,” and “amiable disposition” and said she was “rather a pretty girl” but had been “disfigured by tattooed lines on the chin.” Quashing the rumor it had planted in January, it also stated what no one wanted to ask but everyone wanted to know: “She has not been made a wife …and her defenseless situation entirely respected during her residence among the Indians.”26 Olive, the paper assured readers, had not been raped. The captive was a lady; she had to be, otherwise she would not merit the attention the media eagerly lavished on her stranger-than-fiction story. But she was no less a freak: one Star article described her patience with people who “rush to see her and stare at her, with about as much sense of feeling as they would to a show of wild animals.” Still, the writer noted, “she fully realizes that she is an object of curiosity.”27

In El Monte the Thompsons cared for Olive like a daughter, putting her up in their hotel, the Willow Grove Inn. Ira Thompson was the town’s first postmaster; his hotel both housed the post office and served as a station stop on the Overland Butterfield mail route. Eager to resume her abandoned education, Olive spent much of her time in El Monte writing and studying. She was also driven around Los Angeles in Thompson’s buggy and saw, for the first time, the proto-urban spread of a burgeoning city, including the extravagant adobe homes that ringed the downtown plaza, the Nuestra Senora la Reina de Los Angeles Catholic Church, built in the thirties when California was still Mexican, and the three-story Bella Union Hotel — the first in the city.

As the local agent for the Star, Thompson likely had a hand in arranging Olive’s biggest media splash. On April 19, 1856, the Star ran a two-column front-page story about her experience, based on a lengthy interview. As the longest early article written on her, it serves as a corrective to the racist, religion-soaked tract that formed the core of her popular biography a year later. In vivid detail, the article describes Olive’s “Indian adventures,” from the gory massacre to the girls’ cruel treatment by the “Apaches” to the famine they faced with the Mohaves, detailing how they were forced to throw away their shoes before the Yavapais ran them into the mountains, dripping blood from their lacerated feet, to the way Olive, when her clothes literally fell off her back two weeks later, “matted together the bark of trees and tied it around her person like the Indians.”

Though Olive described the Mohaves as short-sighted farmers and hunters who planted and killed only as much as they needed for the moment, she painted them in otherwise glowing terms. She told the paper about how Espaniole treated her and Mary Ann “in every respect” as his own children. They were not forced to work, “but did pretty much as they pleased.” They shared the Mohaves’ food and were given land and seeds. Twice Olive mentioned how tenderly Aespaneo cared for her. “She speaks of the Chief’s wife in terms of warmest gratitude,” the Star reported, noting that when Olive left, Aespaneo, “the kind woman who saved her life in the famine, cried a day and a night as if she were losing her own child, then gave her up.”

Interestingly, Olive told the Star reporter that the Mohaves always said she was free to leave when she wanted to, but that they would not accompany her to the nearest white settlement for fear of retribution for having kept her for so long. Since she did not know the way, she reasoned, she couldn’t go. But that didn’t explain her disappearance during the Whipple party’s stay in Mohave territory. It’s doubtful that she would have told her white audience — so appalled by her abduction and thrilled by her return — that she had stayed because she wanted to.

The Star story is bookended with strange caveats: it opens by saying that “her faculties have been somewhat impaired by her way of life” and that she was incapable of giving details “unassisted,” implying that words were put in her mouth. The piece ends with the provocative comment, “She converses with propriety, but as one acting under strong constraint.” Unless the reporter simply mistook timorousness for “strong constraint,” Olive may have begun censoring her story already, knowing that not every aspect of Mohave life was suitable for newspaper audiences.

Still, the generosity of the Mohaves impressed at least one reader, who wrote a letter to the editor asking, “Should something not be done in acknowledgment of the Mohave Chief and his noble wife, the benefactors of Olive Oatman? Can anyone read her tale and feel no thrill of gratitude for them?”28

Within a week, four northern California papers had snapped up and reprinted the Star story; others subsequently conducted their own interviews. But in the gap between what was extracted from her and what she withheld, her emotional profile remained vague. “What were her sensations, during all this time, must be imagined; for she is not, as yet, able to express her thoughts in language,” the paper noted. The coverage emphasized her cheery compliance as an interview subject and her frightening adventures as a cultural castaway, but rarely commented on her psychological condition, which was surely shaky. Only private letters and memoirs painted a more nuanced picture. Decades later, Susan Thompson reflected on the time Olive spent at her house in El Monte, calling her “a grieving, unsatisfied woman, who somehow shook one’s belief in civilization.” And, she said, “more savage than civilized,” Olive longed to go back to the Mohaves. Samuel Hughes, who met Olive through Lorenzo, recalled that “she often told me she would like to see some of her old friends, even if they were Indians.”29

In a letter Olive wrote from El Monte to friends in San Diego, she said, “I feel once more like myself since I have risen from the dead and landed once more in a civilized world. … It seems like a dream to me to look back and see what I had ben thrue [sic] and just now waking up.” The letter, which refers to the “blood,” “toil,” and “tears” of her captivity, conveys the racking sense of trauma — if not post-traumatic stress — that attended a life of compound emotional fractures. Though Olive’s dodgy spelling reflects her broken English, one error resonates with her ambivalence about Indians and her contradictory experiences with the two tribes who harbored her: instead of calling the Yavapais “those fiends,” she accidentally wrote “friends.”30

In early June, Olive’s twenty-eight-year-old cousin from Oregon, Harvey Oatman, arrived by steamer in San Pedro to visit the Oatmans in El Monte, presenting family documents to prove his kinship. During a congenial two-week stay, he regaled the siblings with stories of his life homesteading in a budding town called Gassburg, where he and his brother, Harrison, had split a government donation land claim. Neither Oatman had taken to farming, so Harrison had opened a store attached to a saloon and billiard hall, while Harvey ran a hotel directly across from the busy Oregon and California Stage Company.

No doubt Harvey described the Oatman Hotel’s regular dances and the spectacular exhibition held there the previous fall, which included a Drummond light demonstration in which burning lime produced a brilliant white light — limelight — that wowed guests, especially when it threw panoramic projections of European sights against the walls. And he probably mentioned the loquacious (“gassy”) but quite popular and animated innkeeper’s daughter, Kate Clayton — one of the few eligible women in a village dominated by bachelors — who had inspired Gassburg’s name.

By the end of the visit, Harvey had convinced his cousins to return with him to Oregon. Ira Thompson was reluctant to give them up; he was suspicious, the Star reported, that “an attempt was being made to entrap his ward.”31 Thompson published a letter in the Star asking of Harvey, “Where has been his great affection for his cousins for the last three years?” noting that Harvey had told him he had first heard about the Oatman murders in 1853 and knew that Lorenzo, too young to support himself since the massacre, had subsequently traveled to California. “Did he ever spend an hour’s time or one dime to advertise for information in regard to his young cousin that he had all reason to suppose was supported at the expense of the county somewhere in this state?”32

Harvey had no explanation, but defended himself by saying he had no financial interest in the Oatmans — he’d known them before he’d left Oregon for El Monte — and that no state funds had been promised to them; in fact, he’d spent a lot of money on the steamer journey to Los Angeles, and would spend more on three return fares. He did not, however, mention another possible occasion for his newfound concern for his cousins: earlier that year, his brother, Harrison, had survived a violent Indian attack in the Siskiyou Mountains in Oregon at the start of the Rogue River Indians Wars. Harrison and two companions had been hauling flour across the mountains and had stopped to drink at a spring when they were besieged by Indians. The two other men were killed, and Harrison had run down the side of the mountain for shelter.

One of the dead men, who had looked a lot like Harrison but who was now barely recognizable, having been shot in the head, was carried down the mountain and presented to Harvey for identification — as Harrison. Later that day, Harrison, who was resting on the other side of the mountain, sent a letter to his brother explaining that he had survived. Learning how it felt to lose a family member to Indians may have inspired him to reach out to his orphaned cousins.

In late June, the three Oatmans boarded a steamer called the Senator, bound for San Francisco. Olive sat for an interview with the San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin, where her story appeared for the first time in the first person. “My name is Olive Ann Oatman; I was born in Whiteside County, Illinois, in 1838,” she began, and then skipped straight to the day of the massacre and the two captivities. Again she explained that she and Mary Ann were regarded as slaves by the Yavapais and as kin by the Mohaves, saying that Espaniole “took us as adopted children, and we were treated as members of his family.”33 The Oatman trio then took a river steamer to Sacramento, another ship to Red Bluff, and a stagecoach through Yreka. They crossed the Siskiyou Mountains and entered the Rogue River Valley town of Gassburg, population about one hundred, where Olive and Lorenzo would meet Harrison and his wife, Lucena, Harvey’s wife, Lucia, their two boys, and a motley array of homesteaders.

In the end, Thompson need not have worried about Olive’s “entrapment” by her cousin: it was the Methodist minister she would meet in Gassburg who would recognize her potential, seize her story, and control her life for nearly a decade.

FIG. 14. Olive Oatman, soon after her return. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beineke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

FIG. 15. Lorenzo Oatman, soon after Olive’s return. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beineke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.