14

Olive Fairchild, Texan

The handsome woman always wore a dark veil around Sherman to hide her secret. But the secret she hid made her a legend in Arizona, not Texas. | SHERMAN DEMOCRAT, July 4, 1976

Like most nineteenth-century women, Olive’s movements were determined by the men in her life, and the women she befriended tended to fall away from her with each relocation. Her father took her west, Stratton took her east, and when she married John Brant Fairchild, a farmer and rancher from Michigan, she made her home in Texas.

She met Fairchild in late 1864 after lecturing in a church in Farmington, Michigan, just outside of Detroit. His mother and sisters had taken him to see her presentation then invited Olive home to visit. Born in New York to Canadian parents, Fairchild had lost a brother in an Indian battle in Sonora, Mexico, while driving cattle from Missouri to Arizona in 1854. The attack, not far from the site of the Oatman massacre, occurred while Olive was with the Mohaves, and may have played into his attraction to and sympathy for her. Having driven cattle from Los Angeles to northern California during the 1850s, Fairchild had surely heard about Olive’s captivity long before he met her. When he invited her back to Michigan in July of 1865, he proposed. They were married in Rochester in November and returned to live on his farm in Michigan. Olive later called this the happiest period of her life.

If Stratton had controlled the telling of Olive’s Indian history, Fairchild appointed himself its censor. Before the wedding, he bought and burned every copy of the Oatman book he could find, possibly out of shame about his wife’s dark past and her public life. He may simply have wanted to protect her; it probably didn't take long for him to learn that the wounds of her traumatic past were still tender. The Oatman story had served its purpose — notably bringing Fairchild and Oatman together; but it did not reflect well on the society wife Fairchild envisioned for himself as a wealthy businessman. By then, rumors had begun circulating that Olive had left Mohave children behind. In 1863 a Nevada man claimed that he had adopted five Indian orphans in 1858 when he was an agent for the Butterfield Stage Company at Oatman Flat, the newly named site of the Oatman massacre. “One,” he said, “was a beautiful, light-haired, blue-eyed girl, supposed to have been a child of the unfortunate Olive Oatman.” Four of the five children, including the girl, allegedly died from severe diarrhea after being fed only meat.1

Olive’s closest relative, Sarah Abbott, was happy with the marriage, and told her sister in Utah that Olive had “done well in getting a husband.”2 Indeed, Fairchild came from a large and impressive family. His father was a civil engineer and he had three sisters and two brothers, a lawyer and a doctor. Having made money herding and selling cattle, Fairchild had also learned how to invest it. On his return to Michigan from the West, he had become a successful money broker.

Now financially secure, with her book behind her, Olive severed her relationship with Stratton without bothering to tell him about her new husband, much less invite him to the wedding. Her break from Stratton may have resulted from Fairchild’s attempt to suppress her past, but it could have been provoked by Stratton himself, who was spiraling into madness. After his 1864 appointment to the First Congregational Church in Great Barrington, he was recognized as one of the best preachers the church had ever had. When he preached the Sunday after Lincoln’s 1865 assassination, there was reportedly not a dry eye in the pulpit. But his reputation suffered when a female parishioner charged that during his year as an army chaplain he had gambled, bribed an official, and committed adultery. The allegation divided the church, and when Stratton’s accuser refused to testify publicly against him, charges were brought against her. The case, though never resolved, stirred enough controversy that a petition demanding Stratton’s resignation began circulating around the town. He resigned in 1866.

High profile and protracted as it was, the Great Barrington scandal did not destroy Stratton’s career; in early 1867 he was hired at Old South Church in Worcester, Massachusetts. Now nearing forty, he and Lucia had a third son, Samuel. The timing was poignant: the following year the couple learned that their elder son, Albert, who had returned to California to become a schoolteacher, had committed suicide at twenty. From there, Stratton’s life began to unravel. As the church later reported, “serious disability, more or less impairing his usefulness, led to his dismissal” in 1872.3 A family vacation in Germany didn’t help. Soon after their return, a guardian was appointed to Stratton, who was designated “insane” and “incapable of taking care of himself,” then committed to a mental institution.4

Olive was seemingly oblivious to the reverend’s decline. In 1872 the Fairchilds moved to Sherman, Texas, where they settled permanently. A boom town at the junction of several stagecoach lines, Sherman was on a growth spurt in the 1870s, sprouting five flour mills, a huge grain elevator, a steam-powered cracker factory, two secondary schools, and a college. With two other men, Fairchild’s contribution was the City Bank of Sherman, which made him rich. A friend later remembered the Fairchilds as a “romantic” couple — who didn’t socialize. John was handsome, distinguished, and phlegmatic. People called him “Major Fairchild” for no apparent reason. Olive was shy and reclusive. She wore a dark veil when she went into town and walked, said a friend, “with great dignity.” Everyone knew she had been an Indian captive. She was considered warm to those who knew her, but one friend observed that the “sadness of her early experiences never quite lifted.” Another said that “the great suffering of her early life set her apart from the world.”5 She did charity work, taking in and caring for children from the local orphanage, and in 1873 the couple adopted a three-week-old baby girl, Mary Elizabeth (the combined names of the Fairchilds’ respective mothers), whom they called Mamie. Once a Mormon child then a Methodist mouthpiece for Stratton, Olive, like her husband, was now a practicing Episcopalian and had her daughter confirmed in the Episcopal Church. The family lived in an impressive two-story Victorian home, with a well-manicured lawn, flower gardens, and a servant.

fig. 27. The Fairchild home in Sherman, Texas. Olive threw “lawn parties” here for her daughter, Mamie, every summer. Special Collections, University of Arizona Library, Papers of Edward J. Pettid.

Lorenzo hadn’t done as well. Farming in Minnesota had been hardscrabble and, worse, Edna and Lorenzo’s two young sons had died of scarlet fever. “You cannot imagine how lonely we are here this winter with no little darling boy to cheer us in our lonely hours,” Edna wrote in a heart-breaking letter to Sarah Abbott, pleading for a visit. “Here I must sit alone & think if you or some of my sisters were near they would see me quite often.”6

Olive and Lorenzo corresponded sporadically, each claiming the other didn’t keep in touch. A letter to Sarah Abbott from Harrison’s wife, Lucena, confirmed that both were to blame: “I think [Lorenzo] is some[thing] like Olive: rather neglectful about writing to friends.”7

While Lorenzo was struggling to make a living, Olive was battling debilitating eye trouble, headaches, and welling depression. When Mamie was just six, Olive had spent a month in bed because of eye pain and could only see out of one eye for short periods. In 1881, she spent nearly three months, most of them in bed, at a state-of-the-art medical spa in St. Catharines, a resort area known as the Saratoga of Canada, twelve miles from Niagara Falls. Founded by Theophilus Mack, a renowned surgeon and physician who specialized in “women’s diseases,” the Springbank Hotel and Bathing Establishment was as much a sanatorium as a hotel, featuring mineral cures and Turkish baths. Drawing special waters from artesian wells, Mack used water, steam, and electricity to cure rheumatism and “other obstinate diseases.”8

During Olive’s stay at the Springbank, Fairchild wrote to Asa Abbott to tell him she was at a “medical institution,” encouraging him to write her there.9 He was open about Olive’s condition without naming it. But did it have a name? Her treatment suggested she had been diagnosed with what the nineteenth-century neurologist Weir Mitchell called “neurasthenia,” caused by a depletion of the central nervous system’s energy reserves, brought on by the stresses of modern life, with symptoms ranging from weakness and fatigue to headaches and depression. During the last two decades of the century, Mitchell became famous for his rest cure, a medical antidote for cultural and psychological conditions that spanned “hysteria,” postpartum depression, and anxiety. The treatment drew patients, mostly upper-class women ground down by domestic responsibilities, out of their homes and into a regimen of mental and physical inactivity and seclusion, sometimes for months at a time.10

But some men, too, suffered from neurasthenia. Mitchell’s prescription for them was exactly the opposite of the rest cure: they warranted a break from routine — and a trip west. The doctor recommended sleeping beneath the stars, getting food from “the earth,” and pursuing “some form of return to barbarism.”11 It sounded a lot like the life of a Mohave. Paradoxically, the “cure” for men’s neurasthenia may well have been the root cause of Olive’s. Unlike the typical female neurasthenic, who was deemed overwhelmed by the pace of modern living, Olive may simply have been unable to adjust to a life of leisure after growing up among the unconstrained Mohaves and spending her early adulthood as a traveling celebrity. In Texas she personified Thorstein Veblen’s ornamental woman, moneyed and idle, volunteering and running a household. If the effect of this unvaried existence drove many average women to despair, Olive’s history would only have heightened her vulnerability to it, and any number of factors could have exacerbated it: menopause, biochemical depression, or the ripple effects of post-traumatic stress.

Olive’s troubles would ultimately become chronic and multivalent. In 1882, at forty-five, she was agonizing over her mother’s death and yearning for female companionship. As an afterthought to a letter to Sarah Abbott, she scrawled on the envelope, “I long to have my dear mother back. Her memory is so dear to me — all gentleness + goodness. I never felt the kneed [sic] of a mother. I do …so long for a long confidential talk with you.” Her confession that she had never, until then, needed a mother indicated that something in her had slipped. Now nine, Mamie was exactly the age Mary Ann had been when her family was massacred and Olive became her only guardian. When Mamie cried, did Olive hear Mary Ann’s voice as the Yavapais marched her barefoot through the desert?

Then again, Olive’s condition may not have been unique; her loneliness was echoed by other women in her family who had been scattered wide by westward migration. In the 1860s Harrison’s wife, Lucena, had written Sarah Abbott from Oregon, pining for Harvey’s wife, Lucia, who had died in childbirth. After her death, Harvey had disappeared into the mountains, leaving his five children to be fostered out to another family. One of Sarah Abbott’s sisters was off in Utah; the other, Olive’s mother, was long dead. Edna Oatman suffered the loss of her and Lorenzo’s sons with no one to comfort her. As for Olive, her birth sisters were dead and Topeka was locked away in the past. She had lost touch with her close friend from Phoenix, Abi Colver, whom she addressed as “my friend and sister” when she sent her a promotional photo before leaving Rochester, asking her to write.12 Olive’s melancholy may in part have been the burden of the far-flung pioneer woman who had finally arrived — alone.

In the 1880s Olive’s Indian past was publicly revived, retrofitted, and trivialized in what must have been a troubling turn of events. Nora Hildebrandt, the first female tattooed attraction in America, debuted at a dime museum in New York in 1882, wearing 365 tattoos and brandishing a backstory seemingly inspired by Oatman: Hildebrandt claimed to have been captured, with her tattooist father, by Indians, and forcibly tattooed by him at their insistence.13 Unlike Oatman, who had abstract tribal tattoos, Hildebrandt wore decorative popular imagery — birds, scrolls, and flowers indeed rendered by her father, Martin Hildebrandt, a pioneering shop tattooist in New York. Beyond the wild Indians and the compulsory tattoos, her story posed a prickly parallel to Oatman’s; Olive’s father had ultimately caused her to be tattooed — by recklessly marching her into the desert without protection.

The most famous of the early tattooed circus women, Irene Woodward, who followed on Hildebrandt’s heels, also implicated her pioneer father, somewhat incestuously, in her marking. He had supposedly tattooed her as a child to keep track of her in the wilds of Texas, and (unlike most early tattooed ladies) she claimed to have liked it: “At first the father implanted a few stars in the child’s fair skin. Then a picture was indelibly portrayed by the father’s hand,” her broadside read. Delighted, Woodward urged him to continue. “It was an occupation that filled many idle hours, and work continued until the skin was lost in a mass of tattooing that covered the girl’s entire body.”14 Both Hildebrandt and Woodward depicted themselves as motherless children; their tattoos represented just one of the primitive things that could happen to a girl in the Wild West without the civilizing influence of a mother — things that had happened to Oatman.

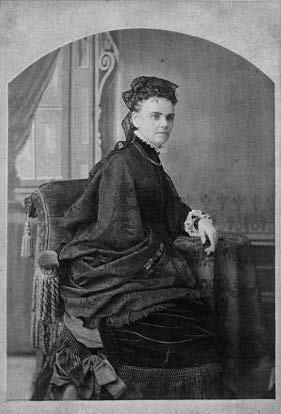

FIG. 28. Olive Fairchild at forty-two, with her tattoos concealed. Courtesy of Dorothy Abbott Fields.

The tattooed captive became a common circus theme throughout the 1880s and ’90s. Other attractions used similar fictions to cast themselves as victims of “redskins,” rather than self-made freaks who, after the invention of the tattoo machine in 1891, could get a full body suit in a matter of weeks. Their stories turned, provocatively, on the notion that people of color could transform whites into people of color — ethnically and decoratively, as a means of exploitation and degradation. The opening of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 allowed circuses to crisscross the country, and many now did so with tattooed ladies who appeared with or without broadsides trumpeting their sensational histories, whose skin shows were titillating for more than just the artworks their skimpy outfits exposed. Olive’s fading tattoo had now been overlaid with associations no lady hoped to abide.

Perhaps the only thing worse than becoming an unwilling member of a subculture of circus freaks was being reported to have died in an insane asylum — a rumor (planted by the writer E. J. Conklin in his 1878 Arizona travelogue Picturesque Arizona) that trailed Olive for a lifetime — and beyond. The prominent historian Hubert Howe Bancroft perpetuated it in books published in 1882 and 1889 and it was even revived in the preface to a 1935 edition of The Captivity of the Oatman Girls, decades after Oatman’s death.15 Friends of the Fairchilds in Sherman were aghast at first hearing it and Fairchild tried his best to correct it. Olive’s reaction to it was never recorded. The rumor carried a morbid irony: in 1875, forty-eight-year-old Stratton had indeed died in an asylum, having been institutionalized for two years, during which time, said his obituary, “he gradually sank away, his death being attributed to a paralysis of the brain.”16 Try as she had, Olive had not completely broken her ties with her ghostwriter; Stratton had appropriated her tragedy in life then imparted his own to her in death.

Unlike Olive, Lorenzo had maintained his affection for Stratton through the years and named his son, Royal Fairchild Oatman, after him in 1883, eight years after Stratton’s death. “Roy” was the couple’s only surviving child of four; their third boy had been thrown from a wagon and killed over a decade earlier. From their childhoods as orphans to their adulthoods as mourning parents, the two seemed doomed to a life of serial tragedy, but around this time they found their financial and geographical footing. Having abandoned farming, Lorenzo and Edna moved to Montana, where they ran a boarding house, then moved to Red Cloud, Nebraska, to buy and run a series of hotels, including the Royal Hotel, whose restaurant was a favorite haunt of Willa Cather. Lorenzo’s correspondence with Olive was still spotty. In 1889 she said she hadn’t heard from him in over two years, and tisked, “I don’t know why he does so, unless he thinks it’s cute to be odd. He used to want to be like old Lorenzo Dow [an eccentric minister for whom he was named]. But I think for such oddities, the day is past. Edna writes when she can, poor woman. She has always worked too hard. Mamie and I both write to her occasionally.”

In the fall of 1888, Harrison Oatman and his seventeen-year-old daughter, Lucina, came visiting. Now a successful and well-known real-estate broker, Harry and his family had moved to Portland. His trip east, which started at Coney Island and ended in Texas, was written up in the Morning Oregonian. He told the paper he approved of Texas’s strong democratic tendencies, but concluded there was no place like Oregon. Harvey had resurfaced in Arizona during the 1860s, threatening to rebury the Oatmans and provide a new marker for the graves, but soon disappeared; he never stayed in one place — or one marriage — for long, and the family ultimately lost track of him.

Though Olive’s health troubles persisted throughout the 1880s, she managed to function not only as a wife and mother but also doing what she called “my work” in charity. Mamie attended the newly founded St. Joseph’s Academy, and Olive threw a lawn party for her every summer. When her daughter turned sixteen, Olive wrote with pride to Sarah Abbott, “Mamie is doing nicely in school and is doing good work in her music. I think, looking with a mamma’s eye, she plays beautifully. We gave her a birthday last Friday. Just to think she is 16 years old and will soon think she is grown, I presume.”17 Olive sounded busy — often her letter-writing was interrupted by visitors. But soon after, in a letter to Sarah, written in perfect penmanship, Mamie wrote that she and her mother had hoped to go to Detroit that summer after six years without a visit, noting, “Mama has not been feeling very well but I think she has been too busy visiting.”

They made the trip after all, spending months with the Fairchild family in Detroit instead of returning to Illinois, where Asa Abbott had died that spring. When Mamie finished school in the early ’90s, she continued to live at home, assisting her mother, who was now having heart trouble.

Though the book was long out of print, the Oatman story was still making the rounds. In 1893, the Arizona Republican reprised it, this time assigning Lorenzo as well as Olive tattoos and claiming that a “half-breed” working at a meat market in Phoenix was rumored to be one of Olive’s three lost sons.18 Five years later the same paper ran another mangled version of the story, in which Olive and Lorenzo were the captives, and Lorenzo was said to have become a Methodist minister who had lectured on the topic over the past ten years. The source of the account was a man who claimed to have been the first to discover the Oatman bodies after the massacre. In the 1890s, Lorenzo was asked to recount the details of the drama and wrote it out on hotel stationery for posterity, himself botching or forgetting some of the facts, which had grown hazy with age.

FIG. 29. Sarah and Asa Abbott, Olive’s maternal aunt and uncle. Courtesy of Edward Abbott.

The Oatman story wasn’t the last of the women’s captivity narratives. Sarah Wakefield’s 1864 Six Weeks in the Sioux Teepees: A Narrative of Indian Captivity, was an interesting follow-up to The Captivity of the Oatman Girls because Wakefield said about the Sioux — forcefully, unapologetically, and without the interference of a male editor — what Oatman only implied about the Mohaves: that they treated her well, that Chaska, her Sioux protector during the six-week Dakota War of 1862, should be rewarded “in heaven” and that she had no regret for defending him afterward, even though she was derided for it. “I should have done the same,” she wrote, “for the blackest negro that Africa ever produced; I loved not the man, but his kindly acts.”19

Wakefield’s story also confirms the social attitudes that likely prevented Oatman from expressing her powerful feelings for the Mohaves after four formative years among them: having claimed that she came to “love and respect” the Indians “as if they were whites,” and after defending Chaska, who had protected her and her children during her captivity, Wakefield was vilified as an “Indian lover,” and Chaska, who had surrendered, was hanged.20

In 1866 Cynthia Parker’s eponymous story of her Comanche “captivity” was written by James T. DeShields. The book was published a few years before Parker starved herself to death, having failed to reassimilate after her forced return to white culture after twenty-four years; the book barely tapped the depths of Parker’s sadness. But where the text failed, the frontispiece succeeded: a photo of Parker shows a bronzed, careworn woman nursing a baby, her hair cropped short as a Comanche expression of mourning.

One of the most sensational captivity stories was published a little more than three hundred years after Mary Rowlandson’s pioneering colonial classic. The plotline of Emeline Fuller’s 1892 Left by the Indians was not unlike Oatman’s, though Fuller was held captive to wild nature, not savage Indians. After a string of Indian raids on the Oregon Trail in 1860, Fuller was orphaned at thirteen and led a baby and four children into the wilderness with scattered members of other families. Like Oatman’s, her narrative was written — and probably embellished — by a minister. But for sheer horror, Fuller’s ordeal outstripped every woman’s Indian massacre tale before it: she had eaten the flesh of her own siblings to survive.

Oatman was neither as heroic as Mary Jemison, the most famous acculturated captive, during her captivity, nor as devastated as Parker on her repatriation. She was not a vindicator like Hannah Dustan, who escaped her captivity by axing — and scalping — ten Abenaki Indians before stealing away into the cool Canadian night in 1697. The triumph of Oatman’s story was in what she achieved both as a captive and on her return. She assimilated twice: first, as a Mohave, where the evidence is overwhelming that she was fully adopted into the tribe and that she ultimately considered herself a member. She was taken at a vulnerable age, had no known family to return to, and bonded with the family that both rescued her from the Yavapais and gave her their clan name. She submitted to a ritual tattoo, bore a nickname that confirmed her insider status, and declined to escape when the Whipple party appeared in the valley or through the many Quechan runners or local Mexicans who could have carried a message to Fort Yuma for her. By the time Francisco came looking for her, Olive had become a Mohave, and almost certainly didn’t want to go “home.”

Her second, perhaps more difficult, assimilation occurred after her ransom, when she was plucked from her tribe against her will. Willing ransomees did not cry on their return, pace the floor in tears at night afterward, or rush to shake the hands of their former oppressors years later. But there was simply no running back to the Mohaves from Los Angeles, or from Oregon, and the social and financial rewards Oatman reaped for turning her back on the Mohaves were tangible and immediate, while the risks of declaring herself an Indian lover were tremendous. In an act of self-preservation, she was able to cross back over and make herself a life first as a public figure, then as a working woman helping orphans, and finally as a mother, giving her own orphan child the unconditional love her mother, and Aespaneo, and Sarah Abbott, in turn, had given her.

In her later years, Olive’s failing health was evident in her spidery handwriting and her frequent references to punishing headaches. “I have been so very nervous and my general health has been poor,” she wrote to the elderly Sarah Abbott in 1898, the year Olive turned sixty. Two years later, her confidante and surrogate mother died. The following year, sixty-five-year-old Lorenzo, who was busy building a ten-thousand-dollar brick luxury hotel in Red Cloud, fell ill and also died. A front-page, two-column obituary in the Red Cloud Chief called him “one of the best known hotel men in the valley,” and quickly segued into a partial retelling of the Oatman saga, promising the full story later. The next day, the paper ran a six-column “sketch” of Oatman, predicting that his “name will go down in history as one of a very few,” and offering an account of the Oatman massacre largely in his own words, adapted from The Captivity of the Oatman Girls.”21 The town of Red Cloud shut its doors on the day of his funeral.

FIG. 30. Lorenzo Oatman in Nebraska. Courtesy of Dorothy Abbott Fields.

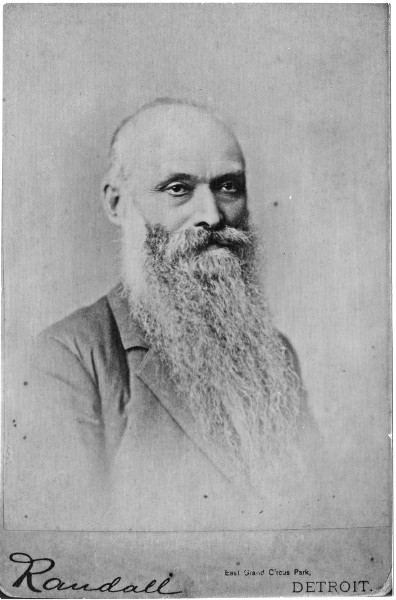

FIG. 31. John Fairchild. Sharlot Hall Museum photo, Prescott, Arizona.

Olive became increasingly reclusive in her later years and, unlike Lorenzo, never discussed her family’s past. “I used to sit by the fire, when a child, watching Mrs. Fairchild and admiring her kind and gentle ways,” wrote a Fairchild family friend. “Her sweet face was surrounded by beautiful white hair like a halo. The tattoo had faded to a pale blue, and of course I was so used to seeing it I didn’t even notice it anymore.”22 In 1903, she died of a heart attack. Her obituaries — one in the Sherman Daily Register the day after her death, another in the Sherman Weekly Democrat five days later — suggested that her husband was still censoring her story: they made no mention of the Oatman massacre.23

Ever Olive’s protector, Fairchild, who feared the Mohaves would come to reclaim their lost daughter after her death, had her coffin sealed in iron and marked her grave at Sherman’s West Hill Cemetery with a thick granite tombstone. But in a touching concession to her true identity, he inscribed it with her birth name — and claimed her as his own:

Olive A. Oatman

Wife of J. B. Fairchild

1837–1903

Five years later, after a day at the office, Fairchild died in bed at seventy-seven. Mamie moved to Detroit, married in 1908, and later that year gave birth to a daughter — her only child — who lived for just a few days. Her name was Olive.